April 14, 2011

John Gaventa on invited and claimed participation

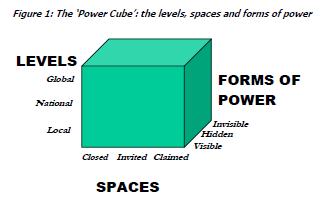

Today, I will be interviewing John Gaventa at a Tisch College forum to which all are welcome. Gaventa has been a major figure in democracy and popular education since his student days in the early 1970s. One of his recent contributions is the PowerCube, a simple device that activists can use for analysis and planning:

I am especially interested in the dimension that runs from "closed" to "invited" to "claimed." Much of my work has involved trying to get powerful institutions to "invite" public participation by, for example, reforming elections to make them more fair, enhancing civic education, advocating changes in journalism, or recruiting citizens to deliberate about public policy. Increasingly, I believe that democratic processes must be claimed, not invited, if they are to be valid and sustainable.

For instance, in 2009, angry opponents of health care reform deliberately disrupted open "town meetings" convened by Democratic Members of Congress. The Stanford political scientist James Fishkin published an argument for randomly selecting citizens to discuss health care instead of holding such open forums. That was a classic proposal for "invited" democracy. The New York Times chose to give his essay the headline, "Town Halls by Invitation." I would now say that democratic participation cannot be by invitation--it must be a right claimed or created by ordinary people, whether elites like it or not.

On the other hand, when officials do invite participation, that is often in response to public pressure or demand. In such cases, formally "invited" spaces are actually claimed ones. One of the most important innovations is Participatory Budgeting (PB). As I understand it, the Labor government of Porto Allegre, Brazil, invented PB to reduce political pressure on itself as it faced hard budget choices. But PB became so popular that it survived changes of party control in Porto Allegre and spread to many other municipalities around the world. In such cases, reform begins with an invitation but becomes an expectation.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: deliberation , democratic reform overseas

February 8, 2011

educating for civility

I am concerned about civil society and active citizenship, not about civility per se. I think an obligation to be polite can suppress engagement or can favor one side over the other (normally the side that is invested in the status quo). Sometimes, an angry critique is just what we need.

But there is a sense of "civility" that means a willingness to listen to others and learn from them. Civility in that sense is vital unless one is certain one is right. Only a few people should enjoy that certainty. (For example, Frederick Douglass appropriately refused to hear or answer arguments in favor of slavery.)

Anyway, I have generally avoided debates about civility, but I was persuaded to write a chapter on the topic for a volume entitled Educating for Deliberative Democracy, edited by my friend Nancy Thomas. The book is now out. It is not available online, but Wiley has chosen my chapter as their free online excerpt (PDF).

permanent link | comments (0) | category: deliberation

October 19, 2010

deliberation on campuses

"Public deliberation" is a positive synonym for "talk"; and definitions of "public deliberation" tend to list positive characteristics like fairness, non-coercion, freedom of speech, seriousness, relevance, use of valid information, and civility. Since these are supposed to be characteristics of academic discourse, as well, it is natural to try to bring public deliberation to college campuses as a form of civic education and as a service to broader communities.

The Journal of Public Deliberation devotes a whole new special issue to the topic, with articles on everything from an overview of the prevailing practices to academic libraries as hubs of deliberation. For full disclosure, eight of the authors are friends and collaborators of mine, but I think the quality is objectively high.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: academia , deliberation

August 12, 2010

what is the best participatory process in the world?

The Bertelsmann Foundation--the largest foundation in Europe, I believe--will give its Reinhard Mohn Prize in 2011 to the best project anywhere in the world that "vitalizes democracy through participation." I am serving on an advisory board for the prize, but a major aspect of the competition this year is open and public. You can go to this website and nominate a project or read and vote on the nominees (or both).

I personally nominated the Unified New Orleans Plan, which was written after Hurricane Katrina by thousands of citizens whom AmericaSpeaks convened for town meetings; Community Conversations in Bridgeport, CT; and deliberative governance in Hampton, Va. These are strongly institutionalized, politically significant examples of public deliberation in the US. They have recruited diverse and representative citizens in large numbers, addressed real problems, and strengthened their communities' civic cultures.

There are 78 other nominees right now. They include clever ideas, like an online space for citizens of different EU countries to agree to vote together. Promising work comes from unexpected places, like a deliberative polling exercise at the municipal level in China. There are many e-democracy platforms, most of which seem to be suites of online tools for following the government and discussing issues. The Danish Board of Technology, which has an impressive track record of public engagement over many years, convened people in 38 nations to discuss global warming together--an impressive experiment that yielded news reports in many of the countries.

Participatory Budgeting (which gives citizens the right to allocate public funds in deliberative meetings) has spread from its homeland of Brazil to places like Tower Hamlets, London and the Indian state of Kerala. Some important legislative reforms have been nominated and should be celebrated, although I am not sure they meet the criteria of the prize. The Central Information Commission in India is an example.

I am not sure that my own nominees are the best, but I am most enthusiastic about all the examples that are multidimensional, lasting efforts, driven by several institutions instead of only the government, and involving work, cultural production, and education as well as dialogue and advice. Some examples other than my own nominees would include Co-Governance in Belo Horizonte, Brazil, perhaps the Abuja Town Hall Meetings in Nigeria (if they are genuine democratic spaces), and Toronto Community Housing’s Tenant Participation System.

Vote for your favorites!

permanent link | comments (0) | category: deliberation , democratic reform overseas

June 3, 2010

AmericaSpeaks: Our Budget, Our Economy

My post for the day is over at usabudgetdiscussion.org, the blog for the National Town Meeting on Our Budget, Our Economy that AmericaSpeaks is organizing for June 26, 2010. This national deliberation will occur simultaneously in about 20 large venues "across the country, in many Community Conversations, and online."

I conclude my post by saying, "I am confident [that citizens] will address this difficult, divisive, and complex topic just as they handle equally challenging questions at the local level--with maturity, civility, and collective wisdom. They will model a whole new form of politics that we desperately need."

permanent link | comments (0) | category: deliberation

May 12, 2010

creating informed communities (part 3)

This is the third of five strategies proposed to achieve the goals of the Knight Commission on the Information Needs of Communities. See Monday's post for an overview.

Strategy 3: Invest in Face-to-Face Public Deliberation

Today I focus on a particular recommendation in the Knight report, number 13, which is: "Empower all citizens to participate actively in community self-governance, including local 'community summits' to address community affairs and pursue common goals."

Face-to-face discussions of community issues have been found to produce good policies and the political will to support these policies, to educate the participants, and to enhance solidarity and social networks. In the terms of the Knight Report, they turn mere information into public judgment and public will. I'm still moved by the Australian participant in a planning meeting who said, "I just can't believe we did it; we finally achieved what we set out to do. It's the most important thing I've ever done in my whole life, I suppose" (quoted in Gastil and Levine 2005, p. 81).

I agree with the Report: "As powerful as the Internet is for facilitating human connection, face-to-face contact remains the foundation of community building." The whole array of online communications contribute to civil society, but dedicated online deliberative spaces--despite some potential for improvement--have been basically disappointing so far. The open ones are subject to pathologies that you don't often see in the physical world. For example, the White House open government forum on transparency was almost hijacked by proponents of legalizing marijuana (PDF, p. 9). In a face-to-face setting, especially in a discrete physical community, it would be very difficult to swarm a public session in that way.

In order to make real-world deliberations work, several conditions must be met. There must be some kind of organizer or convening organization that is trusted as neutral and fair and that has the skills and resources to pull off a genuine public deliberation. People have to be able to convene in spaces that are safe, comfortable, dignified, and regarded as neutral ground.

There must be some reason for participants to believe that powerful institutions will listen to the results of their discussions. They may be hopeful because of a formal agreement by the powers that be, or even a law that requires public engagement. Or they may simply believe that their numbers will be large enough--and their commitment intense enough--that authorities will be unable to ignore them.

There must be recruitment and training programs: not just brief orientations before a session, but more intensive efforts to build skills and commitments. Ideally, moments of discussion will be embedded in ongoing civic work (volunteering, participation in associations, and the day jobs of paid professionals), so that participants can draw on their work experience and take direction and inspiration from the discussions. There must be pathways for adolescents and other newcomers to enter the deliberations.

We have examples:

- Bridgeport, CT--an old port and manufacturing city of 139,000 people--was a basket case in the 1980s. It was hard hit by the loss of manufacturing jobs, crime, and the flight of middle-class residents to the suburbs. The city literally filed for bankruptcy in 1991. The next mayor was sentenced to nine years in federal prison for corruption. The schools were so troubled that 274 teachers were arrested during a strike in 1978.

Bridgeport is now doing much better, to the point that its school system was one of five finalists for the national Broad Prize for Urban Education in both 2006 and 2007. A major reason for Bridgeport’s renaissance is active citizenship.

In 1996, a local nonprofit group called the Bridgeport Public Education Fund (BPEF) contacted organizers who specialize in convening diverse citizens to discuss issues, without promoting an ideology or a particular diagnosis. No one knows how many forums and discussions took place in Bridgeport, or how many citizens participated, because the 40 official “Community Conversations” were widely imitated in the city. But it is clear that at least hundreds of citizens participated; that many individuals moved from one public conversation to another; and that some developed advanced skills for organizing and facilitating such conversations. A community Summit convened in 2006--fully ten years after the initial discussion--drew 500 people. The mayor, the superintendent, the city council, and the board of education had agreed in advance to support the plan that participants developed. [See Will Friedman, Alison Kadlec, and Lara Birnback, Transforming Public Life: A Decade of Citizen Engagement in Bridgeport, CT, Case Studies in Public Engagement, no.1, Public Agenda Foundation, 2007; and Elena Fagotto and Archon Fung, “Sustaining Public Engagement: Embedded Deliberation in Local Communities,” an Occasional Research Paper from Everyday Democracy and the Kettering Foundation, 2009]

So far, I have described talk, but the civic engagement process in Bridgeport involves work as well. Each school has an empowered leadership team that includes parents along with professional educators. The professionals take guidance from public meetings back into their daily work. People who are employed by other institutions, such as businesses and religious congregations, also take direction from the public discussions. Meanwhile, citizens are inspired to act as volunteers. The school district has a large supply of adult mentors, many of them participants in forums and discussions. In turn, their hands-on service provides information and insights that enrich community conversations and improve decisions. Bridgeport’s citizens have shown that they are capable of making tough choices: for instance, shifting limited resources from teen after-school programs to programs for younger children. There is much more collaboration today among businesses, nonprofits, and government agencies. Everyone feels that they share responsibility; problems are not left to the school system and its officials. The School Superintendent says, “I’ve never seen anything like this. The community stakeholders at the table were adamant about this. They said, ‘We’re up front with you. The school district can’t do it by itself. We own it too.’” [Friedman, Alison Kadlec, and Lara Birnback]

- Hampton, VA, is an old, blue-color city of about 145,000 people. Like its fellow port city of Bridgeport, 465 miles to the north, Hampton has struggled with deindustrialization, although Hampton benefits from Army, Air Force, and NASA facilities within the city.

When Hampton decided to create a new strategic plan for youth and families in the early 1990s, the city started by enlisting more than 5,000 citizens in discussions that led to a city-wide meeting and then the adoption of a formal plan. “Youth, parents, community groups, businesses, and youth workers and advocates … met separately for months, with extensive outreach and skilled facilitation.” [Carmen Sirianni and Diana Marginean Schor, “City Government as an Enabler of Youth Civic Engagement: Policy Design and Implications,” in James Youniss and Peter Levine, eds., Engaging Young People in Civic Life (Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 1999)]

The planning process ultimately created an influential Hampton Youth Commission (whose 24 commissioners are adolescents) and a new city office to work with them. The Youth Commission sits on top of a pyramid of civic opportunities for young people. There are also community service programs that involve most of the city’s youth; empowered principals’ advisory groups in each school, a special youth advisory group for the school superintendent, paid adolescent planners in the planning department, and youth police advisory councils whom the police chief contacts whenever a violent incident involves teenagers. Young people are encouraged to climb the pyramid from service projects toward the citywide Commission, gaining skills and knowledge along the way. Political engagement is so widespread that almost 80 percent of Hampton’s young residents voted in the 2004 election, compared to 43 percent in Virginia as a whole. The system for youth engagement won Hampton Harvard’s Innovation in Government Award in 2007.

Engagement is not limited to young residents. When Hampton’s leaders decided that race relations and racial equity were significant concerns in their Southern community that was about half White and half African American, they convened at least 250 citizens in small, mixed-race groups called Study Circles. The participants decided that there was a need to build better skills for working together across racial lines, so they created and began to teach a set of courses--collectively known as “Diversity College”--that still trains local citizens to be speakers, board members, and organizers of discussions. [William R. Potapchuk, Cindy Carlson, and Joan Kennedy, “Growing Governance Deliberatively: Lessons and Inspiration from Hampton, Virginia,” in Gastil and Levine, 2005, p. 261]

Hampton’s neighborhood planning process has broadened from determining the zoning map to addressing complex social issues. Planning groups include residents as well as city officials, and each may take more than a year each to develop a comprehensive plan. Like the young people who helped write the youth sections of the City Plan, the residents who develop neighborhood plans emphasize their own assets and capabilities rather than their needs. There is an “attitude of ‘what the neighborhood can do with support from the city’ rather than ‘what the city should do with the neighborhood watching and waiting for it to happen.’” [Potopchuk, Carlson, and Kennedy, p. 264.]

Hampton has thoroughly reinvented its government and civic culture so that thousands of people are directly involved in city planning, educational policy, police work, and economic development. Residents and officials use a whole arsenal of practical techniques for engaging citizens—from “youth philanthropy” (the Youth Commission makes $40,000 in small grants each year for youth-led projects), to “charrettes” (intensive, hands-on, architectural planning sessions that yield actual designs for buildings and sites). The prevailing culture of the city is deliberative; people truly listen, share ideas, and develop consensus, despite differences of interest and ideology. Young people hold positions of responsibility and leadership. Youth have made believers out of initially suspicious police officers, planners, and school administrators. These officials testify that the policies proposed by youth and other citizens are better than alternatives floated by their colleagues alone. The outcomes are impressive, as well. For example, the school system now performs well on standardized tests.

I would draw the conclusion that is also implicit in the title of Carmen Sirianni's recent book, Investing in Democracy. You can't get "community summits" and other forms of excellent engagement on the cheap. They take a long-term effort and resources that are normally a mixture of money, policies, and people's volunteered or paid time.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: deliberation

April 30, 2010

community organizing and public deliberation

Matt Leighninger, director of the Deliberative Democracy Consortium, has written a wise and inspiring paper called Creating Spaces for Change for the Kellogg Foundation. It is the product of several meetings in which community organizers interacted with people who define their roles as promoting public deliberation. The tensions between these two conceptions of "democracy"--and the potential for melding them--have interested me for many years. I've addressed the topic in published writings, e.g., here. But Matt's report breaks new ground.

Deliberative democracy first arose as a response to a blinkered notion of politics as mere power. The dominant view of political scientists during the 1950s and 1960s was that individuals and organizations want things. They have options, such as to vote, to contribute money, to run for office, to strike, to sue, or to threaten violence, and they make their choices in order to get as much of what they want as possible. Political outcomes are the result of many simultaneous choices.

Deliberative democrats criticized that theory from a moral perspective, saying that we should not be satisfied with policies that arise because individuals and groups try to get what they want. They may not want good things; their power is starkly unequal; and some of their tactics are unethical. Besides, people don't know what they want until they have communicated with others. So we should talk and listen before we try to get things.

But talk can be very harmful, as when evil dictators talk their followers into murderous action. Thus a crucial second step for deliberative democrats is to define some kinds of communication as better than others and to name the better kinds "deliberation." Typically, the hallmarks of deliberation include the diversity of the participants, their equality of influence, freedom of speech, openness and transparency, reasonableness, and civility.

There is now a field devoted to organizing tangible public deliberations at a human scale: meetings, summits, "citizens’ juries," community dialogues, moderated online forums, and various hybrids of these. They all involve convening diverse groups of citizens and asking them to talk, without any expectation or hope that they will reach one conclusion rather than another. The population that is convened, the format, and the informational materials are all supposed to be neutral or balanced. There is an ethic of deference to whatever views may emerge from democratic discussion. Efforts are made to insulate the process from deliberate attempts to manipulate it.

In contrast, activism or advocacy implies an effort to enlist or mobilize citizens toward some end. At their best, advocates are candid about their goals and open to critical suggestions. But they are advocating for something. Many advocates for disadvantaged populations explicitly say that deliberation is a waste of their limited resources. They note that just because people are invited to talk as equals, the discussion will not necessarily be fair. Participants who have more education, social status, and allies may wield disproportionate power. Individuals and groups who are satisfied with the status quo have an advantage over those who want change, because they can use the discussion to delay decisions. (They can "filibuster.")

Talking with people who hold different views can cause us to temper or censor our sincere views in order to avoid confrontation; and such self-editing reduces our passion and our motivation to act. Social movements that oppose injustice seem to arise when "homogeneous people … are in intense regular contact with each other." (Doug McAdam, John D. McCarthy, and Mayer N. Zald, 1996).

For their part, proponents of deliberation often see organized advocacy as a threat to fair and unbiased discussion; hence they struggle to protect deliberative forums from being "manipulated" by groups with an agenda. One tactic for this purpose is to select potential participants randomly (like a jury), so that it is impossible for an interest group to mobilize its members to attend. Overall, deliberation seems cool, cerebral, slow, and middle-class. Activism seems urgent, passionate, effective, and available to all.

Community organizing is a type of activism. It is concerned with just social outcomes (not just processes). But many community organizers have deep concerns about respecting all voices, including ideologically diverse ones, building trust and networks among fellow citizens, and developing civic skills that include skills of listening and collaborating. Thus the gap between deliberation and community organizing can be very small. After one meeting that Matt describes, Eduardo Martinez of the New Mexico Forum for Youth and Community (a community organizer) remarked, "We may use different terminology and have different local issues, but most of the discussion was about how similar our work is."

Another organizer, Jah'Shams Abdul-Mumin, nicely articulated the limitations of both fields in making a case for combining them: "The organizing community often treats people in a pejorative manner. Meanwhile, the deliberative democracy crowd includes a lot of extremely intellectual types. Neither group owns up to the things they can do better to relate to people."

There were, evidently, tough discussions about the value (if any) of neutrality and whether concern for social equality needs to be built into deliberative processes. There were also debates about what to call the whole field that includes both deliberation and community organizing. "Civic engagement" seems too dry; "citizenship" can be understood as exclusive and merely legal. Nobody knows what "deliberation" is, and "community organizing" has perhaps "been stretched so far over the last forty years that it has lost much of its meaning." But overall, there seems to have been much enthusiasm for the idea that issue advocacy, community organizing, deliberative democracy, and racial equity may be parts of one larger cycle or ecosystem--a "wheel of engagement," as some called it.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: deliberation

April 14, 2010

AmericaSpeaks national discussion of the budget and the economy

AmericaSpeaks, a group that promotes public deliberations, will organize a national discussion about the budget on June 26, 2010. Americans will meet in large groups in up to 20 different cities, and also in online discussions and smaller community conversations. All the discussions will be linked, which is a new frontier in public deliberation.

The topic is of fundamental importance, because we cannot avoid deep decline as a nation unless we make difficult choices regarding the budget. Our political leaders and institutions are plainly incapable of doing the hard things, like cutting entitlements or raising taxes. And the public seems to want them to do nothing painful. As a board member of AmericaSpeaks, I will vouch for the neutrality and high-quality of their background materials and facilitation. This national discussion should yield truly thoughtful, informed public opinion and public will.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: deliberation

April 9, 2010

classroom practice from an ethical perspective

(Madison, WI) I am here for one of a series of meetings organized by University of Wisconsin Professor Diana Hess and funded by the Spencer Foundation. Diana and her colleagues have assembled remarkable empirical data about high school students and their social studies classes. From their longitudinal surveys--which follow the students into their twenties--they can draw inferences about the effects of various school experiences. Their elaborate interviews of students and teachers and their classroom observation notes help to explain the quantitative data and also provide numerous interesting anecdotes. The interviews, in particular, draw attention to dilemmas. Should you deliberate issues in a classroom that may be offensive to some students? Should you allow students to deliberate issues that should be settled? Should a teacher disclose his or her personal views?

The empirical data are relevant to these questions. For instance, it might turn out that teachers' disclosing their opinions affects students' opinions. But the data cannot settle these questions, which also involve value judgments about both means and ends. The appropriate ends, in particular, are by no means clear.

Therefore, Diana and her colleagues have assembled professional philosophers to discuss the empirical data with the researchers. There are actually three kinds of background in the room. Almost all the participants have personal experience as teachers. The quantitative data is more general and systematic but less rich than personal experience. And everyone has some level of philosophical training or interest. This seems to me a model for how to think about thorny issues.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: deliberation , education policy

April 7, 2010

participatory budgeting in Chicago

Participatory budgeting started in Brazil, when residents of poor urban neighborhoods were given control over capital budgets. They now meet in large groups and decide how to spend government funds deliberatively. The outcomes of participatory budgeting in Brazil include better priorities, greater public trust in government, and much less corruption. The last benefit might seem surprising, but it appears that when people allocate public money, they will not tolerate its being wasted.

Participatory budgeting is one of many important innovations in governance that have originated overseas and that should be imported to the US. Now is a time of great creativity in democratic governance, with the US generally lagging behind. We suffer from too limited a sense of the options and possibilities.

I believe there has been some participatory budgeting in California cities. And now Chicago Alderman Joe Moore announces:

As a Chicago alderman, I have embarked on an innovative alternative to the old style of decision-making. In an experiment in democracy, transparent governance and economic reform, I'm letting the residents of the 49th Ward in the Rogers Park and Edgewater communities decide how to spend my entire discretionary capital budget of more than $1.3 million.

Known as "participatory budgeting," this form of democracy is being used worldwide, from Brazil to the United Kingdom and Canada. It lets the community decide how to spend part of a government budget, through a series of meetings and ultimately a final, binding vote.

Though I'm the first elected official in the U.S. to implement participatory budgeting, it's not a whole lot different than the old New England town meetings in which residents would gather to vote directly on the spending decisions of their town.

Residents in my ward have met for the past year — developing a rule book for the process, gathering project ideas from their neighbors and researching and budgeting project ideas. These range from public art to street resurfacing and police cameras to bike paths. The residents then pitched their proposals to their neighbors at a series of neighborhood "assemblies" held throughout the ward.

The process will culminate in an election on April 10, in which all 49th Ward residents 16 and older, regardless of citizenship or voter registration status, are invited to gather at a local high school to vote for up to eight projects, one vote per project. This process is binding. The projects that win the most votes will be funded up to $1.3 million.

I am strongly opposed to discretionary budgets for legislators. That's just a way for them to buy reelection with public funds. But the fact that Alderman Moore has such a budget is not his fault, and he is using it for an excellent experiment.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: deliberation , democratic reform overseas

March 17, 2010

public deliberation news

In lieu of a substantive post on this busy day, some links about public deliberation ... A new CIRCLE study finds that reorganizing a high school to encourage daily meetings about school policy boosted voluntary service. ... The deliberative democracy field responds to the Coffee Party movement. ... Detroit has a new plan for school reform that was developed in a highly deliberative way.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: deliberation

January 22, 2010

student conference on deliberation

One of the highlights of last summer was a fascinating conference called No Better Time, which convened scholars, activists, leaders, and students who are committed to deliberation. Hundreds of people met at the University of New Hampshire for a rich set of discussions and working groups.

The student participants banded together and decided to create a national conference of their own. It's called Connect the Dots, and it will be held on March 3-6, 2010, Point Clear, Alabama. They are calling it "A national student conference on public dialogue, deliberation, community problem solving and action." It should be fantastic. Students, faculty, and practitioners should apply to present.

The host of the conference is the David Mathews Center. David is now the president of the Kettering Foundation and was the president of the University of Alabama in the 1970s. The center named for him is located in Tuscaloosa. Its "purpose is to foster infrastructure, habits, and capacities for more effective civic engagement and innovative public decision making."

permanent link | comments (0) | category: deliberation

December 7, 2009

what the leaked climate change emails tell us about our politics

Imagine that you are a specialist in climate science. Like 82 percent of your colleagues, you believe that "mean global temperatures [have] risen compared to pre-1800s levels, and ... human activity [has] been a significant factor in changing mean global temperatures." You worry about the consequences, which may range from acute suffering in the world's poorest countries and loss of natural species to global catastrophe.

You also know what science is like--it is always uncertain and provisional. Every article has a "limitations" section, every data table has margins of errors and sources of bias, and rarely do two articles precisely agree. Nevertheless, you know that to change the course we're on will require millions of people to alter their political and consumer preferences. But people are fairly selfish and short-sighted. Besides, we have lots of other things to worry about, from our day-to-day practical struggles to spiritual concerns, plus all the alarms we receive from the mass media: serial killers, terrorist attacks, corrupt politicians, swine flu.

Given all this clutter, you, the climate scientist, decide that you'd better become much more effective at communicating a sense of alarm. You are constrained by ethical limitations (no outright lying, for instance, even to save the planet), but simplification, evasion of complexity, exaggeration of certainty--all that seems necessary.

These are the habits that one can see in the leaked private emails of climate scientists. Their messages include mentions of "tricks" in the presentation of data, data withheld from direct public inspection, and references to skeptics as "idiots." Reactions to the emails range from George F. Will (the documents "reveal paranoia on the part of scientists ... [N]ever in peacetime history has the government-media-academic complex been in such sustained propagandistic lockstep about any subject") to Paul Krugman ("all they show is that scientists are human, but never mind").

In my view, the emails reveal a shift from one kind of communication to another. Borrowing a distinction from the contemporary German philosopher Jürgen Habermas, I'd distinguish strategic, instrumental, means/ends communication from deliberation or dialog. When communication is strategic, you know what your goals or ends are, and you use efficient means to convince others. When communication is dialogic or deliberative, you reason with the other party about what the goals and means should be.

The leaked climate emails show scientists becoming strategic rather than dialogic. The reason is clear: modern society is so structured that strategic communication generally beats dialog, at least in the short term. It simply works better.

Yet strategic communication is unethical, insofar as it tries to manipulate the other person's reasoning capacity. It uses him or her as a means, not an end. It is also self-destructive in the long term. Our views of matters like climate change depend fundamentally on trust. I cannot directly sense changes in the climate, let alone their causes. Neither can scientists--despite their fancy equipment. An account of how and why the climate is changing requires aggregating the research of many scientists and collaborative teams. To use the aggregated information, you must trust all the contributors. Then, to make matters even harder, people like me don't read any of the scientific literature on climate. We read what we regard as high-quality news coverage of the scientific literature, which means that we must trust some reporters, as well as the scientists they cover. And we must trust the reliability of the relationship between them.

All of this works if we assume that scientific discourse and high-quality journalism are not strategic forms of communication. They are not supposed to pre-judge the outcome and try to convince. Rather, they are supposed to explore the truth in the company of their readers. To the extent that they communicate strategically, they are just interest groups, basically like all the others. They have goals; they may be willing to negotiate; but they cannot persuade on the basis of trust.

This analysis suggests a real dilemma. Dialogic communication won't change mass opinion, and counting on it may put the earth at risk. But strategic communication is unethical and ultimately self-defeating. It's the nightmarish side of modernity.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: deliberation

November 9, 2009

Senator Coburn v. the online town meeting experiment

I have enthusiastically summarized a recent NSF-funded experiment in which Members of Congress deliberated with randomly selected citizens about the hot-button issue of immigration. I presented this experiment as "the right way to do a town hall meetings." I noted, as one of the positive outcomes, that participants increased their favorable views of their elected officials as a result of the online deliberations. (We know that is a real effect because there was a randomly selected control group that didn't deliberate.)

I should have seen the objection coming. In fact, it came on the floor of the US Senate, presented forcefully by Senator Tom Coburn (R-Texas), and was then picked up by prominent blogs and mass media. One of the study's authors, David Lazer, has even graphed the way Coburn's speech diffused across cyberspace:

The critical argument is nicely summarized on the Heritage Foundation's web site: "This report urges Congressmen not to actually interact with their constituents, but to avoid them altogether by holding safe townhalls they can completely control. ... Congress is actually using your tax dollars to pay social scientists to find ways they can avoid actually talking to their constituents while improving their chances of reelection." Senator Coburn even used this project as an example of why the NSF should not fund political science at all.

On his blog, Lazer summarizes the various criticisms and responds with commendable civility. For my part, I would say: It was not a good thing in itself that participants became more supportive of Members of Congress. Some Members deserve low support--their reelection rate is, if anything, too high. But it is a good thing that people were able to exchange ideas and values in a civil format with national leaders. This is an educational process for both sides.

I mentioned the fact that politicians' approval ratings rose because I do not think they will be instinctively enthusiastic about this kind of format. Contrary to the fears of the Heritage Foundation, politicians cannot control a true deliberative forum.* Thus we are not likely to see many online deliberations unless Members of Congress stand to gain somehow from participating. It was helpful to learn that their approval ratings rose, because that might motivate them to do more deliberations.

I can grasp a purist argument that any government is prone to protect its own interests, and therefore we should be vigilant about any effort that uses tax dollars and improves the reputation of incumbents. But if we are concerned about the unfair advantages of incumbents, the obvious issues to address are gerrymandered electoral districts, the huge fundraising imbalance, and free mailings for Members of Congress (the "franking privilege").

When incumbents choose to do things that citizens actually like--such as deliberating online; or passing good legislation--their approval is likely to rise, but we can hardly complain. In Federalist 27, Hamilton writes, "I believe it may be laid down as a general rule that [citizens'] confidence in and obedience to a government will commonly be proportioned to the goodness or badness of its administration." If deliberation is a form of "good administration," it will increase confidence in and obedience to the government. That sounds like a good sign.

----

*Heritage is concerned that "off-topic, redundant, unintelligible, or offensive questions were screened." They're worried that an angry opponent of federal policy would be blocked. Lazer responds, "As noted in the report, the possibility of screening anything as 'offensive' was theoretical. We did not actually exclude any questions for this reason. ... That said, it is worth noting that the medium is potentially manipulable, and there is nothing to stop someone who is doing an online townhall from excluding difficult questions. (Of course, all communication media are manipulable in some way, so it is not obvious that this is an advantage or disadvantage of online townhalls.) We had a neutral moderator, and included all questions that time would allow, in the order that were posted. This included some that were pretty hostile to the Member. Our assessment (and recommendation) was that these very confrontations made the events more effective, because they reflected the authenticity of the event. In short, the Members approval ratings increased because they had done the right thing."

permanent link | comments (0) | category: deliberation

October 27, 2009

the right way to do a town meeting

Last summer, Democratic Members of Congress fanned out across the country to conduct "town meetings" on health care. They already knew which policies they supported, so these events were not actually the public deliberations that the term "town meeting" implies. They were opportunities for highly motivated individuals to sound off, one at a time, with an elected official in shouting range and cameras rolling. This was a disaster waiting to happen, and not only for the Democratic politicians who organized the "town meetings." I presume that most of the citizens who attended--including the most conservative ones--were pretty dissatisfied as well.

Not long before, the Congressional Management Foundation and a crack team of researchers had conducted an entirely different kind of congressional town meeting--on the equally controversial topic of immigration. People were randomly invited to participate, so as to create a representative group. Balanced materials were provided, and the discussions were moderated. Members of Congress participated but did not moderate. Everything took place online.

The researchers evaluated this experiment carefully, using a randomly selected control group. Here are the findings that I found most striking:

- Underrepresented people chose to participate. Younger Americans, lower-income people, racial minorities, women, individuals who do not attend religious services, and people with weak or no partisan affiliations were more likely to participate--in contrast to elections, when all of these groups are less likely to vote.

- The discussions were substantive, civil, and well-informed. Participants liked them.

- Participants' opinions of the politicians with whom they deliberated rose dramatically. Participants also came closer to agreeing with these politicians about the issue under consideration. They were more likely to vote in November (compared to the randomly selected control group), and more likely to vote for the politician with whom they had deliberated. Thus the payoffs for politicians were very favorable--in contrast to the results of last summer's "town meetings," which verged on disastrous.

Use a sham process, and you will pay a price. Risk a real discussion, and people may agree with and respect you.

Download Online Town Hall Meetings: Exploring Democracy in the 21st Century here. And here are some related blog posts by me and others: why have town meetings at all?, responses of the deliberation community to last summer's events, and another important academic study by the authors of the new "Online Town Meetings" paper.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: deliberation

October 8, 2009

who wants to deliberate?

Michael Neblo, Kevin Esterling, Ryan Kennedy, David Lazer, and Anand Sokhey have written a really important paper entitled "Who Wants to Deliberate - and Why?" It is a rich and complex document that reports the results from a new national survey plus an experiment.

Overall, the paper complicates and challenges the "Stealth Democracy" thesis of John R. Hibbing and Elizabeth Theiss-Morse (my review of which is here). The "Stealth Democracy" thesis is that people have the following preferences:

- Best: government by disinterested, trustworthy elites. Second-best: direct democracy (referenda, etc.) to keep the actual corrupt elites in check. Worst: Participatory democracy that requires a lot of talk and work by citizens.

On the basis of their survey data, Hibbing and Theiss-Morse conclude that "getting people to participate in discussions of political issues with people who do not have similar concerns is not a wise move." Deliberative democracy "would actually do significant harm." According to the new paper, however, citizens hold ambivalent and complex feelings about each of the options listed above; and they are quite supportive of a fourth choice--deliberative representative democracy (a conversation between citizens and elected officials.)

One way to get a flavor of this fascinating paper is to compare survey questions from Hibbing and Theiss-Morse with new questions from Neblo et al:

- Hibbing and Theiss-Morse: "Elected officials would help the country more if they would stop talking and just take action on important problems. [86% agree]

- Neblo et al: "It is important for elected officials to discuss and debate things thoroughly before making major policy changes." [92% agree]

- Hibbing and Theiss Morse: "What people call “compromise” in politics is really just selling out one’s principles." [64% agree]

- Neblo et al. "One of the main reasons that elected officials have to debate issues is that they are responsible to represent the interests of diverse constituencies across the country." [84% agree]

- Hibbing and Theiss-Morse: "Our government would run better if decisions were left up to nonelected, independent experts rather than politicians or the people." [31% agree, which Hibbing and Theiss-Morse consider high.]

- Neblo et al: "It is important for the people and their elected representatives to have the final say in running government, rather than leaving it up to unelected experts." [92% agree]

By asking questions that are opposites of Hibbing and Theiss-Morse's items, Neblo et al. reveal that even most people who hold anti-democratic views are actually quite ambivalent. Most of those people also hold pro-democratic views. One way to make sense of the apparent contradiction is to think that people are in favor of real dialog and deliberation, but unimpressed by the actual debate in Congress. That, by the way, would be roughly my own view.

The other main source of evidence in Neblo et al is a field experiment, in which people were offered the chance to deliberate with real Members of Congress. They were more likely to accept if they had negative attitudes toward elected leaders and the debates in Washington. Again, that could be because they don't reject deliberation in principle but dislike the official debates that they hear about or watch on TV. People who held those skeptical views were especially impressed by an offer from their real US Representative to deliberate. Individuals were also more likely to accept the offer to deliberate if they were young and if they had low education.

Further, if they showed up to deliberate, their opinions of the experience were very positive. According to the paper, "95% Agreed (72% Strongly Agreed) that such sessions are 'very valuable to our democracy' and 96% Agreed (80% Strongly Agreed) that they would be interested in doing similar online sessions for other issues." These results are consistent with almost all practical deliberative experiments. So are the open-ended responses of participants:

- “It was great to have a member of Congress want to really hear the voices of the constituents.” / “I believe we are experiencing the one way our elected representatives can hear our voice and do what we want.” / “I thought he really tried to address the issues we were bringing up instead of steering the conversation in any particular direction, which was cool.” / “I realized that there are A LOT more sides to this issue than I had originally thought.”

The short answer to the question, "Who wants to deliberate?" seems to be: "A lot of people, but especially those who are most alienated from politics as usual." That suggests that real deliberative democracy, as organized by the National Issues Forums, Everyday Democracy, AmericaSpeaks, and others, may be the best antidote to deep skepticism and alienation.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: deliberation

September 30, 2009

much better than a town meeting

If you or a group that you're part of wants to discuss health care policy without descending into the kind of shouting matches that dominated August, the Kettering Foundation and the National Issues Forums have just the tools you need. Click through to a work book, other background materials, and a guide to holding a neutral, productive dialog in your community.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: deliberation

August 12, 2009

why have town hall meetings at all?

Members of Congress are doing their usual thing--holding "town hall meetings" that are really public Q&A sessions on major pending issues. This summer, the main topic is health care reform. What is unusual is the hostile reception that politicians are experiencing (although I'm not sure what proportion of the negative comments are truly inflammatory ones, like those covered in the media). As a result, some Members have already decided not to hold town hall meetings at all, and the whole practice might soon disappear. That prospect leads Matt Yglesias to reflect:

Members of Congress are doing their usual thing--holding "town hall meetings" that are really public Q&A sessions on major pending issues. This summer, the main topic is health care reform. What is unusual is the hostile reception that politicians are experiencing (although I'm not sure what proportion of the negative comments are truly inflammatory ones, like those covered in the media). As a result, some Members have already decided not to hold town hall meetings at all, and the whole practice might soon disappear. That prospect leads Matt Yglesias to reflect:

I don’t understand why members of congress are holding these town halls. There’s been so much focus on the spectacle of the whole thing that nobody’s really stepped back and explained what the purpose of these events are other than to give us pundits something to chat about. Obviously this is not a good way of acquiring statistically valid information about your constituents’ opinions. And it doesn’t seem like a mode of endeavor likely to increase the popularity of the politician holding the town hall. The upside is extremely limited, and you’re mostly just exposing yourself to the chance that something could go wrong.

Yglesias is asking how politicians benefit from these events (in a narrow sense). A more important question is whether town meetings have public benefit--which would offer a different kind of reason for holding them. I would say ...

On one hand, there is no good reason to hold the kind of "town meetings" we are used to. That phrase invokes the old New England deliberative forums in which citizens come together to make collective decisions. The reality, however, is a public hearing with a small group of self-selected activists who ask questions one by one. That format is easy to manipulate and likely to turn unpleasant; it rewards strategic behavior rather than authentic dialog; and it reinforces a sense that the politician and citizens are profoundly different. (The politician has responsibility but cannot be trusted; citizens have no power but only a right to express individual opinions.)

On the other hand, we need real public discussions that include politicians along with other citizens. The purpose of such discussions is not to find out what the public thinks already. As Yglesias says, a random-sample poll is better for that. And its purpose is not to sell the public on a position; for that, mass advertising works better. The purposes of discussion are rather to encourage people to see issues from other perspectives from their own, to develop new and better ideas, to enhance voters' ability to judge their representatives as deliberators, and to strengthen local ties and relationships that lead to civic change. For example, citizens who discuss health care reform might not only develop opinions about federal legislation but also decide to launch a new initiative in their town.

Without deliberation, as Madison warned, "The mild voice of reason, pleading the cause of an enlarged and permanent interest, is but too often drowned, before public bodies as well as individuals, by the clamors of an impatient avidity for immediate and immoderate gain."

To achieve deliberation, process is important. People need to talk among themselves in diverse groups, whether in study circles, National Issues Forums, or at tables in a 21st Century Town Meeting organized by AmericaSpeaks. There must be moderators and good background materials. Elected representatives should be observers, or maybe peer participants, but not lone figures on the stage.

The Obama Administration could have used public deliberation as a way of getting a health care bill. That would have required a large-scale, organized public discussion with moderators and rules. The Administration chose, instead, to drive the bill through Congress quickly, using their mandate. They may succeed, and there was a case for speed. But they have encountered--not only organized ideological opposition--but also deep public distrust of government. If they fail, this will be the cause.

Here are two potential "theories of change":

1. Run a presidential campaign promising to expand the role of government in health care, get more than half the electoral votes and seats in Congress, write and pass the bill, and trust that the results will ultimately be beneficial enough that people will come to like and trust the new federal health care program.

2. Try to build a health reform plan in dialog with the public by organizing a large-scale deliberation about the content of the bill and by considering participatory mechanisms for the ongoing delivery of health care. (Co-op insurance plans might have potential for that purpose.)

The Administration chose the former strategy, and we'll see if it works. I hope it does, because I think the House bill will benefit the public if passed. It is also possible that a deliberative process would have been subverted by partisan and ideological forces (although there are techniques that can protect deliberation to a degree). At any rate, I hope the Administration will try a deliberative approach to some other issue.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: deliberation

July 31, 2009

private opinion polls

These results from the latest New York Times survey are supposed to be evidence that "the public continues to be ill-informed and hypocritical."

People want lower taxes, no spending cuts, and a smaller deficit. It's like the citizen who was quoted in a newspaper many years ago saying, "It's the government's deficit, not ours. Why can't they pay it off?"

Others have already made the following technical point. Few individuals in this survey probably gave inconsistent responses. The overlap between those who wanted "no new taxes" and those who opposed spending cuts may have been fairly small. It was the aggregate result that was incoherent, and that was no individual's fault.

Which brings me to a second, more substantial point. We must aggregate public opinion to get democratic outcomes. But we can aggregate in many different ways. One of the stupidest ways would be to call people on their home phones, out of the blue, and ask them a series of abstract questions. "Do you want lower taxes, yes or no?" "Do you want service cuts, yes or no?" If you tally up the answers and call it public opinion, that is a recipe for incoherence. You will get much better results if, for example, you ask a group of people to think, talk, and develop a consensus plan.

Nina Eliasoph's comments from Avoiding Politics (p. 18) are relevant:

Research on inner beliefs, ideologies, and values is usually based on surveys, which ask people questions about which they may never have thought, and most likely have never discussed. ... The researcher analyzing survey responses must then read political motives and understandings back into the responses, trying to reconstruct the private mental processes the interviewee 'must have' undergone to reach a response. That type of research would more aptly be called private opinion research, since it attempts to bypass the social nature of opinions, and tries to wrench the personally embodied, sociable display of opinions away from the opinions themselves. But in everyday life, opinions always come in a form: flippant, ironic, anxious, determined, abstractly distant, earnest, engaged, effortful. And they always come in a context--a bar, a charity group, a family, a picket--that implicitly invites or discourages debate.

In the case of the New York Times poll, the context is a very cerebral, information-rich, nonpartisan, published forum in which authors and readers are expected to think like ideal legislators and make all-things-considered judgments under realistic constraints. In that context, you look like an idiot if you call for lower taxes, more spending, and a reduced deficit. Into that august forum are dragged innocent citizens who were telephoned randomly without notice and asked to say yea or nay to a bunch of sentences. No wonder that, when their responses are tallied, they look "ill-informed and hypocritical." I guarantee you that if the same people were told they needed to come up with a public position on the federal budget, their response would not only be better--it would have a human face and would be presented with some mix of seriousness, uncertainty, regret about difficult choices, and pride in their accomplishment.

To be sure, the poll gives meaningful information. It tells us what people want when they don't reflect--and most of us do not reflect on national policy very often. So the opinions in the poll pose real problems for national leaders, who cannot deliver desirable outcomes that are practically incompatible. On the other hand, people rate their own understanding of national policy very poorly. They expect good leaders to make tough calls. They realize that the situation is difficult and there are no perfect answers. If you conclude from these survey results that the public is stupid and should be treated accordingly, you misread their mood and their expectations.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: deliberation , populism

July 28, 2009

deliberation and the California budget mess

A concrete proposal for a deliberative public forum made it to today's Times op-ed page. Chris Elmendorf and Ethan J. Leib call for a "citizens assembly" that would meet when the legislature deadlocks on a budget. The California legislature needs a two-thirds vote to pass a budget and labors under many constraints created by initiatives. It has a chronic problem of failing to pass decent, reasonable budgets on time, a problem that reached a critical stage this year when the largest American state issued IOUs in lieu of real checks.

Other activists are causing for a constitutional convention--which could be called the "nuclear option" of public deliberation, because it would enlist a deliberative group in blowing up the whole constitution and starting over. The Elmendorf and Lieb proposal is much more modest. In fact, it might cause elected officials to propose moderate budgets in order to avoid a deadlock and then a loss of power to the citizen's assembly.

I presume citizen participants would be randomly selected and paid for their time. They would consider various alternative budgets, hear from experts, talk (a lot), and decide. As a populist reform, it beats the initiative and referendum on two grounds. First, it's deliberative--people exchange ideas and evidence before they vote. Second, the subject of deliberation is the whole budget, not an individual yes-or-no proposition like capping taxes or reducing class sizes. You're really not acting responsibly as a participant in self-government unless you are willing to make tradeoffs.

Whatever one thinks of this particular proposal, I would argue that California's problems are civic, not economic. Legislators could balance the budget by raising taxes and/or cutting spending; they don't need aid from outside, which would only encourage them to continue their irresponsibility. Their civic problems lie partly in the rules of the formal political system, but another cause is a relatively weak civil society. The newspapers that cover state and metropolitan issues are inadequate, for example. Californians have plenty of civic assets, as well, but they need to mobilize them much better.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: deliberation

June 3, 2009

on the limits of online forums

The White House recently created a space where anyone could post "ideas and comments on how to make government more transparent, participatory and collaborative." More than 2,000 ideas were posted. I was happy to participate; my ideas are here.

The site is a gesture in favor of openness, deliberation, and interactivity. But the results so far are at least somewhat problematic. They underline the importance of deliberations or discussions in which the participants are representative of the whole population and there is some moderation.

The very top vote-getter was proposed by "republicanleaderjohnboehner." It is a "72-hour mandatory public review period on major spending bills." I do not know whether that is a good idea. The explanation seems a bit partisan: the main example of a "taxpayer-funded outrage" is "the empty 'Airport for No One' in the congressional district of Democratic Rep. John Murtha (D-PA)." (Note the double identification of Rep. Murtha as a Democrat--both before and after his name.) 1201 people voted for this idea, 187 against it.

The Republican House leader had a right to participate in this dialogue; arguably, it is a good innovation to create an open space where he would be able to weigh in. But without prejudice against Mr. Boehner's idea, I suspect that it got so many votes because someone activated an an online Republican network to support it.

The second-rated idea was to legalize marijuana, which seems unrelated to the purpose of the site and must also reflect the activation of a network or a mailing list. It could indeed turn out that the number of votes was proportional to the size of one's network. (I used my blog and facebook page and got a total of 139 favorable votes.)

There were many cranky "proposals." For instance, 53 voted for, and 10 against, a proposal headed, "Obama may be Kenyan. His father is Kenyan. Obama is not natural born! Release [birth certificate]." My proposal to engage young Americans got comments like this one: "Stop spending money on racist preemtive genocidal wars. We need education not war." Whoever wrote this comment had a right to express himself. I disagree that the current US wars are "genocidal," but I'm not on the opposite side from this person. I would question whether (a) the comment was germane and relevant, and (b) whether a dialogue in which such views are prevalent can possibly influence national policy.

The important next step of the White House process is a "discussion phase." It will be very interesting to see how this works.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: deliberation

April 1, 2009

controversy in the classroom

According to my blurb on the back cover:

- Controversy in the Classroom is a model of scholarship. Diana Hess combines her personal experience as a teacher with rigorous qualitative and quantitative data and philosophical argumentation to conclude that students must learn to be citizens by discussing controversial issues. This is an important and neglected finding that should influence parents, teachers, and policymakers.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: advocating civic education , deliberation , education policy

February 24, 2009

the politics of negative capability

Zadie Smith's article "Speaking in Tongues" (The New York Review, Feb 26) combines several of the fixations of this blog--literature as an alternative to moral philosophy, deliberation, Shakespeare, and Barack Obama--and makes me think that my own most fundamental and pervasive commitment is "negative capability." That is Keat's phrase, quoted thus by Zadie Smith:

- At once it struck me, what quality went to form a Man of Achievement especially in Literature and which Shakespeare possessed so enormously—I mean Negative Capability, that is when man is capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.

Other critics have noted Shakespeare's remarkable ability not to speak on his own behalf, from his own perspective, or in support of his own positions. Coleridge called this skill "myriad-mindedness," and Matthew Arnold said that Shakespeare was "free from our questions." Hazlitt said that the "striking peculiarity of [Shakespeare’s] mind was its generic quality, its power of communication with all other minds--so that it contained a universe of feeling within itself, and had no one peculiar bias, or exclusive excellence more than another. He was just like any other man, but that he was like all other men." Keats aspired to have the same "poetical Character" as Shakespeare. Borrowing closely from Hazlitt, Keats said that his own type of poetic imagination "has no self--it is every thing and nothing--It has no character. … It has as much delight in conceiving an Iago as an Imogen. What shocks the virtuous philosop[h]er, delights the camelion poet.” When we read philosophical prose, we encounter explicit opinions that reflect the author’s thinking. But, said Keats, although "it is a wretched thing to express … it is a very fact that not one word I ever utter can be taken for granted as an opinion growing out of my identical nature [i.e., my identity]."

In Shakespeare's case, it helps, of course, that he left no recorded statements about anything other than his own business arrangements: no letters like Keats' beautiful ones, no Nobel Prize speech to explain his views, no interviews with Charlie Rose. All we have is his representation of the speech of thousands of other people.

Stephen Greenblatt, in a book that Smith quotes, attributes Shakespeare's negative capability to his childhood during the wrenching English Reformation. Under Queen Mary, you could be burned for Protestantism. Under her sister Queen Elizabeth, you could have your viscera cut out and burned before your living eyes for Catholicism. It is likely that Shakespeare's father was both: he helped whitewash Catholic frescoes and yet kept Catholic texts hidden in his attic. This could have been simple subterfuge, but it's equally likely that he was torn and unsure. His "identical nature" was mixed. Greenblatt argues that Shakespeare learned to avoid taking any positions himself and instead created fictional worlds full of Iagos and Imogens and Falstaffs and Prince Harrys.

What does this have to do with Barack Obama? As far as I know, he is the first American president who can write convincing dialog (in Dreams from My Father). He understands and expresses other perspectives as well as his own. And he has wrestled all his life with a mixed identity.

Smith is a very acute reader of Obama:

- We now know that Obama spoke of Main Street in Iowa and of sweet potato pie in Northwest Philly, and it could be argued that he succeeded because he so rarely misspoke, carefully tailoring his intonations to suit the sensibility of his listeners. Sometimes he did this within one speech, within one line: 'We worship an awesome God in the blue states, and we don't like federal agents poking around our libraries in the red states.' Awesome God comes to you straight from the pews of a Georgia church; poking around feels more at home at a kitchen table in South Bend, Indiana. The balance was perfect, cunningly counterpoised and never accidental.

The challenge for Obama is that he doesn't write fiction (although Smith remarks that he "displays an enviable facility for dialogue"), but instead holds political office. Generally, we want our politicians to say exactly what they think. To write lines for someone else to say, with which you do not agree, is an important example of "irony." We tend not to like ironic leaders. Socrates' "famous irony" was held against him at his trial. Achilles exclaims, "I hate like the gates of hell the man who says one thing with his tongue and another in his heart." That is a good description of any novelist--and also of Odysseus, Achilles' wily opposite, who dons costumes and feigns love. Generally, people with the personality of Odysseus, when they run for office, at least pretend to resemble the straightforward Achilles.

But what if you are not too sure that you are right (to paraphrase Learned Hand's definition of a liberal)? What if you see things from several perspectives, and--more importantly--love the fact that these many perspectives exist and interact? What if your fundamental cause is not the attainment of any single outcome but the vibrant juxtaposition of many voices, voices that also sound in your own mind?

In that case, you can be a citizen or a political leader whose fundamental commitments include freedom of expression, diversity, and dialogue or deliberation. Of course, these commitments won't tell you what to do about failing banks or Afghanistan. Negative capability isn't sufficient for politics. (Even Shakespeare must have made decisions and expressed strong personal opinions when he successfully managed his theatrical company). But in our time, when the major ideologies are hollow, problems are complex, cultural conflict is omnipresent and dangerous, and relationships have fractured, a strong dose of non-cynical irony is just what we need.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: Barack Obama , Shakespeare & his world , deliberation , philosophy

January 19, 2009

discussion and service on MLK Day

USA Service.org, the official site that promotes service activities on Martin Luther King Day, was kind enough to ask me to post a blog entry over the weekend. I reproduce it here as an appropriate offering for today:

Between now and January 19th, we’ll feature a series of guest bloggers on USAservice.org. Today we’re pleased to share a post by Peter Levine, Director of Research and Director of CIRCLE (Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning & Engagement).

Just a few days before Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, he said:

“It is always a rich and rewarding experience to take a brief break from our day-to-day demands and the struggle for freedom and human dignity and discuss the issues involved in that struggle with concerned friends of goodwill all over our nation.”

We have lost Dr. King, but we must continue that discussion.

I'm Peter Levine from CIRCLE at Tufts University’s Tisch College of Citizenship & Public Service. I also represent a consortium of groups that organize nonpartisan discussions and deliberations in communities around America.

My colleagues and I believe that service is essential, and that it is best when it involves reflection and discussion. This weekend, volunteers can meet to choose their issues and plan their service. On January 19th, after completing a service activity, volunteers can reflect on what they learned and what they should do next. Such discussions can help turn thousands of MLK Day service events into powerful opportunities for learning, analyzing issues, forming human connections, and addressing serious, long-term problems.

Americans who volunteer on MLK Day may plan to conduct additional service together in the months ahead. They may decide to recruit others to join their efforts, conduct research, create public art and media to inform people about their cause, make changes in their homes, companies, and careers, advocate for policy changes, or even launch new organizations. They may reflect together on profound issues, like the ones that kept Dr. King thinking, conversing, organizing, and learning all his life.

USAservice.org has posted a great new toolkit to help Americans organize “Citizen Action Conversations” connected to service. The guide is flexible, but it has contains practical ideas for how to organize a productive conversation.

President-elect Obama has said, “I will ask for your service and your active citizenship when I am President of the United States. This will not be a call issued in one speech or one program--this will be a central cause of my presidency.” It is up to each of us to serve and to make our service as meaningful as possible. A great way to start is by combining a service event with a Citizen Action Conversation on this Martin Luther King Day.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: deliberation

January 3, 2009

partisanship and civic renewal

In The American Prospect, Henry Farrell argues that partisan activity is helping to restore "civic engagement"--voting, discussing, and grassroots activism. This is ironic, in his view, since Barack Obama emerged out of a nonpartisan movement for civic renewal and presented himself as somewhat post-partisan on the campaign trail. In the 1990s, Obama had joined Robert Putnam's Saguaro Seminar, one of the important gatherings of intellectuals who tended to view citizenship in deliberative or communitarian terms and who decried hyper-partisanship. According to Farrell, "when Barack Obama speaks about how citizens can transcend their political divisions to participate in projects of common purpose, he is drawing on the arguments and ideas from these intellectual debates of a decade ago." Yet Obama won by tapping the energy of a highly partisan grassroots movement that may now challenge his administration from the left. "Scholars have misunderstood the basis of civil society," Farrell claims. They have hoped for civility, deliberation, and solidarity when competition and debate are more to the point.

I personally believe strongly in the value of political parties, which have the motives and resources to draw people into politics. Parties also provide opportunities for activism and leadership and offer choices to voters on Election Day. As I told the Christian Science Monitor in 2006, "Polarization tends to be a mobilizing factor in getting out the vote." At CIRCLE, we helped to organize randomized experiments of voter outreach with the goal that the parties would learn new techniques and compete more effectively for our target population (youth). I believe we and our colleagues had some influence on the parties and thereby helped boost turnout. We also funded a study that found that parties were under-investing in their young members. Again, our goal was to persuade them to become more effective.

Thus I wouldn't say that Farrell reaches the wrong conclusions, but he does stereotype other scholars of citizenship. He writes, "None of the civic-decline academics, whether they focused on voter participation, social capital, or the quality of deliberation, saw much use for political parties or partisanship." In fact, parties and competition got a lot of positive play within what Farrell calls the "academic movement to reverse civic decline." His list of academics is selective, and some of the ones he mentions are favorable to parties. For instance, Theda Skocpol has written voluminously on parties; she advocates reforms to make them more participatory and competitive. Perhaps, as Farrell says, Robert Putnam "underplayed" the role of parties by depicting them "as merely one form of civic participation among many"--but Putman took a communitarian line that many of his colleagues criticized. For instance, what about Bill Galston, who is not only a political scientist who favors reforms to enhance party competition, but also an active strategist for the Democratic Party? Or what about Barack Obama, who has moved strategically from nonpartisan community organizing to elected office?

Jane Mansbridge was a participant in the discussions that Farrell briefly recounts (including a well-known meeting with President Clinton); and she is perhaps the most famous critic of a narrow definition of "politics" as party competition. Her great early book is entitled Beyond Adversary Democracy. Yet a quick online search of her work yields characteristic passages like this one (pdf):

- Because there are good arguments for the electoral connection, I would never suggest

replacing it. I suggest only that we stress elections less and supplement them with other

forms of citizen interaction with the state. Elections are irreplaceable in democracy at the

very least because parties organize opinion and crystallize issues in the electoral process,

electoral campaigns discover and bring out issues and information that the other side

would like to hide, and, most importantly, votes for representatives have some effect on

political outcomes and are thus deeply legitimating.