September 2, 2008

the role of charity

When Hurricane Gustav set its sights on New Orleans, the national political campaigns and parties instinctively started to raise money for NOLA charities. They were following the example set after Katrina, when the private sector contributed at least $6.5 billion (PDF). (And that doesn't count the market value of volunteer time.) For comparison: the storm did an estimated $150 billion in damage; and the federal government has spent about $120.5 billion on relief (PDF). So the total value of Katrina philanthropy equals about 5% of federal funding.

Classic progressives might say that charity is too scanty, too episodic and unpredictable, and too unfairly distributed to matter much. Our attention should be focused on government aid. High-profile efforts to raise private money are distractions. Democrats should be especially reluctant to raise private money after a crisis, because their role is to put the government under scrutiny.

I only partly agree with this. Federal funding must and did dwarf private funding. But private money is useful for supporting experimental or adversarial activities that the government can't touch. Also, individual contributors and volunteers create contacts and social networks. One local activist, Tim Williamson, said "Pre-Katrina New Orleans was an insular, closed community. .... Katrina has opened up the networks." These human connections can be powerful. Finally, private money can support the kind of leadership and coordination that we normally expect of government. Foundations funded the Unified New Orleans Plan, a highly participatory and deliberative process. Compared to the structures created by local, state, and federal governments, the United New Orleans Plan was much better.

Overall, I would say that we need two things for any major public project (such as rebuilding a city): resources and structure. Resources can come from taxes or from private donors and volunteers. The danger of emphasizing private philanthropy is that it can let the government off the hook. But a balance of private and public funds is valuable.

Structure is at least as important as money and work, and we get structure from laws, regulations, and policies. But it is dangerous for official political leaders to set all the rules and priorities. Certainly, official institutions, from the New Orleans school system to the Army Corps of Engineers, made a hash of the job before Katrina. Governmental policies are generally better when citizens help to shape them more than they did in pre-Katrina NOLA. Besides, governmental policies are not sufficient because private institutions (from colleges and universities to churches) need to set policies and priorities, too. It's important to coordinate across sectors.

The Katrina tragedy showed that government resources were woefully inadequate for the city of New Orleans. But the lack of money wasn't as big a problem as the poor management of public institutions both before and after the storm. Katrina also proved that Americans are generous with their money and voluntary time. But the money and labor wasn't spent as effectively as it should have been, because civil society wasn't adequately organized and participatory.

Ideally, the parties would be debating these issues instead of just dialing for dollars.

permanent link | comments (1) | category: Katrina

April 3, 2007

public participation in planning: lessons from New Orleans

Abigail Williamson, a graduate student at Harvard, has written a study of public participation on the Unified New Orleans Plan (pdf). Here I assume that her narrative is accurate and comprehensive; I use it as the basis for some thoughts about civic engagement and planning.

According to Williamson, there have been three main planning efforts in New Orleans since the hurricane. The first was called "Bring New Orleans Back" (BNOB). It was ordered by the Mayor and run by local experts and leaders--an elite. It has been praised for its technical excellence, but it became highly controversial because it rejected rebuilding some of the flooded neighborhoods that were poor and largely Black. Because it was controversial and lacked political legitimacy, the Mayor distanced himself from it, and it died.

The second planning process was run by a firm called Lambert Advisory. Williamson's interviewees told her that Lambert's process truly reflected input from diverse citizens; but the resulting plan was not satisfactory. (I'm not sure exactly how it failed to measure up.)

The third planning process was designed to be broadly inclusive and technically satisfactory. It started off with some failed public meetings, but then AmericaSpeaks was brought in to organize demographically representative, deliberative sessions involving hundreds of people at once. In the interests of disclosure, I must note that I am a member of AmericaSpeaks' board. But Williamson's study was independently funded and she finds that the meetings truly were representative, substantive, and constructive. One observer recalls:

More than anything, I think the thing I was most impressed with about Community Congress II, in addition to just the sheer numbers they were able to reach, when I went and I walked around, I saw people sitting at tables together of different socioeconomic backgrounds, different parts of town, having healthy discussions. Not necessarily always agreeing, but actually having conversations. Not just rhetoric, not yelling and screaming, but really just having healthy conversations about what they saw as the issue here.

The resulting plan appears to have legitimacy--meaning not that it is necessarily just or smart, but that people believe it arose from a legitimate process. Just for that reason, it appears likely to pass.

This is a major achievement, and it would have been impossible without demographic representativeness and high-profile, large-scale, public events. These events took skill and commitment to pull off. Those are conclusions to emphasize and celebrate. Nevertheless, I'd like to point out some limitations and challenges:

1. Framing the deliberation is tricky. If citizens are asked to produce a truly comprehensive plan (with a map and a detailed budget), then they will essentially govern the city. But no one has elected them, nor will the political leaders yield without a fight. If, on the other hand, citizens generate a plan without details, then they can avoid tradeoffs; and in that case, they aren't really deliberating. Likewise, if citizens are told to work within very "realistic" constraints, they cannot demand justice. For example, if they are told that there is only $x of state money available, they are blocked from saying that the state should be more generous. If, on the other hand, citizens deliberate without constraints, they can invent unrealistic scenarios.

2. A process like this could be manipulated to get results that someone wants. The organizers could manipulate it, or an outside group could get its own people into the meetings. In other words, the legitimacy could be false. I'm committed to AmericaSpeaks and will vouch for this particular process. But the more such deliberations are used to make important decisions, the more people will try to manipulate them.

3. The organizers had to make a prior decision about the definition of "the people." They chose the population that had lived in New Orleans prior to Katrina. Consequently, they aimed for a demographic mix that looked like the traditional city, not like the city today; and they organized town meetings in major diaspora cities from Houston to Atlanta. They could have chosen a different benchmark--current residents, or residents of the whole state, to name two examples. This is essentially a question of values, and it cannot itself be deliberated.

4. Planning is work. That's what was evident at the tables during the Town Meetings--not just talk, but work. However, planning is only one aspect of public work. Buildings must be built, trees must be planted, money must be raised, newsletters must be written, and so on. It's important for this work, not merely the talk, to be democratic and participatory.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: Katrina , deliberation

September 20, 2006

civil society versus the private sector

(Newark, NJ): At Monday's launch of America's Civic Health Index, Bill Galston said that Katrina demonstrated a failure of government and political leadership, but also of civil society, because it displayed our inability (or unwillingness) to work together across differences. Nina Rees, formerly a staffer for Dick Cheney, replied that the "private sector" had performed very well after Katrina, as revealed by the massive amount of philanthropy directed toward New Orleans and the Gulf. I'm with Bill, because I think there's a difference between the total amount of individual voluntary effort (also known as "the private sector") and civil society.

New Orleans is rich in groups and associations that operate within discrete neighborhoods and ethnic communities--including the extraordinary African American mutual benefit societies. But there is, and was, a dearth of civic institutions. New Orleans had few voluntary associations that crossed community lines so that they could coordinate efforts, allocate resources fairly, monitor the government, organize deliberations about justice, encourage citywide solidarity, and develop plans for redevelopment. In the absence of an encompassing civic infrastucture, New Orleans got bad government and ineffective or piecemeal private aid. Thus the Katrina disaster illustrates the importance of decent political leadership, but also the need for a strong civil society that goes beyond charity and volunteering.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: Katrina

February 24, 2006

young people and rebuilding after Katrina

According to the latest AP-Ipsos poll, "About half the under-30 poll respondents -- 52 percent -- said they were confident federal money for the Gulf Coast recovery was being spent wisely. The number was much lower for respondents of all age groups -- only 33 percent."

We have three possible explanations for this gap, which are all quoted in an article by Ryan Pearson for AP's youth-oriented wire service, ASAP news. First, the youngest generation has consistently been less critical of government than older generations. More of them agree than disagree that the federal government usually acts in the genuine interests of the public. (However, a plurality won't answer the question at all because they are undecided). Second, younger people are often less well informed about current events, so perhaps they know less about the mismanagement after Katrina that has been heavily reported in the press. Third, they may be in the middle of a learning process. In the ASAP story, Abby Kiesa mentions CIRCLE's focus groups on Katrina. Abby heard mostly questions rather than firm opinions. Youth wanted to know what was happening after Katrina, why we weren't better prepared, and who was a credible source. As Public Agenda and its co-founder Dan Yankelovich argue, we often make a mistake when we confuse settled opinions with developing views--although they can look alike in a standard survey.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: Katrina

January 23, 2006

opportunity for youth work in New Orleans

"Common Cents is offering grants up to $20,000 for projects that will contribute to an inclusive and just recovery from Hurricane Katrina. Preference will be given to service or advocacy projects that either involve young people meaningfully in the recovery, or that address the specific needs of children and youth. ... All winners will ...

Receive up to $20,000 in cash awards Showcase their project at a student conference in New York City in May 2006

"Preference will be given for projects that ...

Increase youth decision-making in the recovery and rebuilding

Build relationships between people within and outside the region

Strengthen infrastructure for sustainable services for young people

Contribute to our understanding of youth as a resource for recovery

... DEADLINE: FEBRUARY 1"

permanent link | comments (0) | category: Katrina

December 28, 2005

youth-led research after Katrina

My organization, CIRCLE, has made grants to teams of young people who design and conduct community research projects. We are able to make these grants thanks to funding from the Cricket Island Foundation. We also provide the youth teams with some guidance.

Some of our current grantees are a group of homeless youth from New Orleans, who were planning to study the police treatment of their peers (i.e., other homeless young people). Katrina made that research impossible by scattering them across the country. However, they have changed their project to investigate the Katrina experience and its aftermath.

Last week, the Chicago Tribune ran a helpful story on these young people's work. The reporter, Dave Wishnowsky, kindly included some contact information for dispersed New Orleans youth to use if they wanted to be included in the research. The story is entitled "Collecting Katrina memories: Young evacuees plan to write book." You have to register with the Tribune to read the whole story here; but I quote some portions below:

[Matthew] Cardinale, 24, and [Shannell] Jefferson, 21, of New Orleans, are spending this week in Chicago interviewing Katrina evacuees ages 14 to 24 for a project they are hoping to turn into a book."That's what's really unique about this project," Cardinale said about the Hurricane Katrina Evacuee Youth-Led Research Project. "We've got evacuees interviewing evacuees." ...

Cardinale and Jefferson are former residents of Covenant House New Orleans, a homeless shelter for youths.

When Katrina hit in August, Cardinale, a graduate student at the University of New Orleans, was volunteering as a mentor at the shelter. With a $10,000 donation from the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement, he had organized a project for a three-person team of ex-shelter residents, including Jefferson, to research how New Orleans police treated homeless youths.

When Katrina devastated the city, however, the team's plans changed. They decided to instead use the money--plus an additional $7,145 from the same group--to interview young evacuees in Chicago, Houston and New Orleans about their hurricane experiences.

"I think the young people in this whole thing have been overlooked," Cardinale said. "And with this project, this is the first time that a lot of them have had a chance to share their stories. We're giving a voice to so many youths out there, and we're documenting it all."

permanent link | comments (0) | category: Katrina

October 19, 2005

New Orleans: a youth-led rebuilding project

At CIRCLE, we plan to fund some young New Orleanians who were displaced by Katrina to conduct research on the experience of the disaster. The youth we're working with happen to have been homeless before the storm, so their perspective will be interesting. Meanwhile, I have received the following appeal by email. Knowing some of the people involved, I believe I can disseminate it in confidence:

Amid all the confusion in New Orleans, inspiring grassroots projects are taking shape. One inspiring example is the work of students at Frederick Douglass High School who are rebuilding the social fabric of their community in the low-income 9th Ward. A group called Students at the Center, originally a creative writing program based at Frederick Douglass High, a predominately African American school, has dedicated itself to rebuilding their inner-city school and neighborhood.A core group of these Frederick Douglass students, teachers, artists, and parents currently displaced across the country has stayed in communication, and wants to meet face to face in New Orleans so they can assess the damage and plan their next steps to save their community. It is our goal to raise $10,000 to enable 15 to 20 of them to reconnect November 11-13.

"The people of New Orleans will make the decision" of which schools to rebuild or abandon, according to Education Superintendent Cecil Picard ("New Orleans Public School Enrollment May Be Halved," Times-Picayune, 10/13/05). If the families at Douglass High are to have a voice in these decisions, they need your support now. This is a poor neighborhoods without political clout or the resources to travel.

Please contribute $25, $50, $1,000, whatever you can, either by check (see below) or by PayPal on the New Village Press website One hundred percent of your donation (we will pay for PayPal processing) will go directly to airfare, ground transportation, food and lodging for the 3-day gathering. Make checks payable to New Village and designate it for Rebuilding New Orleans Community. We'll keep donors informed about the progress of this project.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: Katrina

September 21, 2005

New Orleans: civic innovation

The reconstruction of New Orleans represents an opportunity to employ techniques for civic participation that have been developed and tested over the last 30 years. For example:

There are excellent methods available for public deliberation. Over the next three months, people from New Orleans who have congregated in cities like Houston could be invited to forums run by AmericaSPEAKS. That's an organization that uses technology to mediate discussions among hundreds or thousands of people who gather in convention halls or other large venues. Meanwhile, dispersed citizens who have Internet access could deliberate online using a mechanism like that of e-thePeople. Finally, small clusters of people could use the Study Circles process to deliberate in living rooms, shelters, and church basements. All these discussions could be framed in the same way, and all the groups (large and small, offline and online) could report their results to a central agency.

I do not mean to suggest that the destruction of New Orleans is in any way a good thing, but we should try to rebuild as well as possible. I'm taking a cue here from E.J. Dionne's interview of Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-OR). Blumenauer sounds like my kind of person: an enthusiast for public participation, an environmentalist who's optimistic that we can make the lived environment better than it was before, a hawk about federal deficits, and a guy who's "always seeking to put together left-right coalitions on behalf of his eclectic mix of ideas." He told Dionne:

I've been in Congress for nearly 10 years and I've never been so optimistic that we have a chance not just to engage in the gargantuan task of helping people in the Gulf, but also of healing the body politic. ... You've got to build a citizen infrastructure along with all the roads and bridges. ... [P]eople should have a role in what it should be like, rather than have it done to them

I don't know if his optimism is justified, but we certainly need ideas, energy, and innovation.

permanent link | comments (2) | category: Katrina

September 16, 2005

New Orleans: federal spending

In the aftermath of Katrina, an emerging line of argument goes like this: Bush is an anti-government conservative. Anti-government conservatives cut spending. Therefore, Bush cut spending. And the flooding has revealed the vulnerability of poor people when government spending is inadequate. I suspect that the real story is somewhat different. Bush is a profligate spender who borrows to finance rising expenditures. Cuts are coming, forced by the debt, but they have not happened yet. Therefore, it is generally inaccurate to attribute current social problems to Bush's spending cuts. The real culprits are decades, even centuries, of under-investment, plus very poorly managed government--both in big cities and, since 2000, at the federal level.

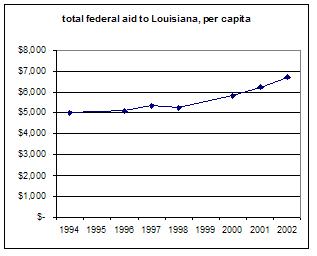

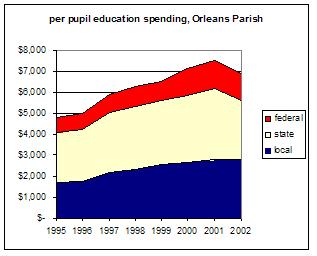

The full story is probably somewhat more complicated, since there have been federal cuts in some programs. I wish that financial data were more widely cited in the debate about what Katrina "means." In my limited discretionary time, I have created two graphs, both of which end in 2002. (More recent data are not easily found.)

The first shows that total federal spending per capita increased in Louisiana through 2002, although these numbers are not adjusted for inflation. Consistently, about 10% of the annual spending is for defense.

The second graph shows that spending per student in the Orleans Parish public schools rose, but then fell in the 2002-3 school year, mainly because of a drop in state support. Again, these figures are not adjusted for inflation.

I acknowledge that these are just snippets of information, and I'd welcome more detail about any actual Bush spending cuts that might have affected citizens of New Orleans.

permanent link | comments (2) | category: Katrina

September 15, 2005

New Orleans: the youth/adult ratio and why it matters

According to the New York Times, in areas of New Orleans where there was significant flooding, the poverty rate was 29%, four out of five residents were people of color, and the ratio of adults to minors was (as I calculate it) 2.58-to-one. That is a similar ratio to what we see in Detroit and Camden, NJ. It is not too far below the national average of 2.5-to-one. But it is quite different from the pattern in wealthier neighborhoods. In contrast to the inner city, some of Detroit's suburbs have four adults per minor. Even the non-flooded parts of New Orleans (where the median income is much higher and about half of the residents are White) have an adult-to-minor ratio of 3.5-to-one.

Why does this matter? Dan Hart and colleagues argue that "child-saturated" communities--those with fewer than three adults per minor--do not provide many adult role models, much adult supervision, or many opportunities for participation in adult-led groups. On the bright side, when there are many youth, they can participate in volunteer activities together and benefit from positive peer role models. Youth are more likely to volunteer than adults; therefore, volunteering is particularly common in youth-heavy communities. But there is an important exception: youth-saturated neighborhoods that are also poor tend to have low levels of civic participation as well as high rates of delinquency. This is probably because young people suffer from the shortage of adult leaders, and there are too few youth organizations with adequate and legitimate funding to absorb most kids. The "autonomous youth culture" is subject to heavy influence by one group of local people who happen to have money and power: criminals.

Thus cities like Detroit and Camden face a shortage of adults along with their other problems. And I suspect that the low adult/youth ratio in New Orleans--which may have dropped further after the evacuation--is an important reason why order broke down there.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: Katrina

September 6, 2005

the politics of the New Orleans disaster

I agree with Maria Farrell and others that the New Orleans disaster has displayed aspects of American life that are grievously wrong. People died because they couldn't afford to leave the flooded city. The government failed to help them, just as it had failed to protect them in the first place. The ones left behind were mostly African American and poor. Until the water destroyed their homes, they had lived in one of America's many ghettos: large, socially isolated areas of poverty and high crime, also marked by very poor municipal services, blighted buildings, and a lack of business investment. I don't think there is anything quite comparable to an American ghetto elsewhere in the developed world. There are poor neighborhoods in Europe, often inhabited by people of color. But they are much smaller and less dangerous than the ghettos of the US.

Obviously, these points have ideological significance. It is usually liberal leaders (along with some interesting libertarians, such as Jack Kemp) who emphasize the need to address massive poverty and racial exclusion. When voters observe the New Orleans ghetto after a disaster and recognize the vulnerability of its citizens, they may move leftward. Since the poverty and vulnerability are real, it is quite appropriate to draw ideological and political lessons from what happened this week. It's also important to argue that people in New Orleans were victimized and are not to blame for the rioting. We want Americans to draw the lesson that inner-cities need more investment, not that the police should be more aggressive.

However ....

1) We shouldn't let the issue become narrowly partisan. True, Bush responded to the crisis in a callow and offensive way; yes, his FEMA director is unqualified compared to James Lee Witt, who served under Clinton; and it's a fact that the budget request of the Army Corps of Engineers was not fully funded. But exactly the same kind of disaster and botched response could have happened under Clinton. Besides, the people of New Orleans have been living under Democratic city and state administrations since Reconstruction. Their schools and police force have been terrible all that time. (I would support spending more per student than the $7,533 allocated by the Orleans Parish schools, and a big increase would require more state and federal aid. But New Orleans' per-student spending has increased by 27 percent since 1999 and has risen faster than the national average. The results remain quite poor and cannot be blamed mainly on the feds.)

I doubt very much that it will work as a political strategy to try to focus blame on the Bush administration. In the short term, predictably, voters are divided along partisan lines in their estimate of Bush's performance. There are so many possible targets of blame (including nature, local government, rioters, and long-standing federal policies) that only people who have a particular ideological frame have focused their anger on the president.

In the longer run, voters' opinions of Bush will become irrelevant. I have always assumed that he would be unpopular by now. But his popularity doesn't matter much. Republicans will run as outsiders in 2006 and especially 2008, when they will probably nominate an anti-Washington governor or a Bush critic like McCain for president. As for Democrats, they have a chance to win if they (a) figure out what they stand for and (b) find a plausible candidate. If they succumb to the temptation to bash the outgoing administration, voters will once again conclude that they have no answers to America's problems.

2) We must respond in a way that will make it possible to rebuild New Orleans in a satisfactory way. That is going to require hope and cooperation. Unless individuals feel hope and solidarity, they will do just what Matthew Yglesias predicts and use their insurance money to move away from New Orleans. Hope should come from the fact that America is not simply "selfish and wicked." It is also a robust democracy with comparatively competent government, strong nonprofit institutions, and an impressive tradition of civic innovation. We are much better than we were 25 years ago at city planning, historic preservation, wetland-conservation, and public engagement. We have models like the Listening to the City process, that convened 800 ordinary citizens to help plan the World Trade Center rebuilding. Even the federal government is getting better at engaging the public.

Anger will be part of any public discussions in or about New Orleans, and genuine rage should not be suppressed. But we cannot afford for outsiders to pursue partisan advantage, because the federal, state, and local governments must work together.

3) There should be an ideological dimension to the debates in town meetings, blogs, and op-ed pages, but there is more than one legitimate ideological perspective to consider. I lean toward the view that people in New Orleans are suffering because of our low levels of public investment and our lack of concern for African Americans. But I know libertarians who think that the New Orleans disaster is an illustration of government's hubris. In classic New Deal style, the feds taxed and spent money to build levees and drain swamps, thus encouraging people to live in a dangerous place, against the logic of both market and nature. Burkean conservatives should want to preserve as much as possible of New Orleans' distinctive heritage. Progressives should argue for rebuilding in new and better ways than before. This debate is interesting and important, but it will accomplish little if it narrows to an argument about impeaching George W. Bush (see these comments for a sample).

permanent link | comments (0) | category: Katrina

September 2, 2005

why there is looting in New Orleans

I'm quoted in a Baltimore Sun article on that topic today: "Behavior of stressed disaster survivors draws eyes of experts," by Linell Smith. Inevitably, only a snippet of what I said found its way into the story. My blog allows me to state my full view.

Stealing other people's property is wrong. But it is happening on a large scale in New Orleans, because ...

1. Some people are stealing to feed themselves and their children. That is such a strong excuse that it usually cancels the fault. Whether people who steal under such circumstances should even feel regret is a subtle question. A mitigating factor like this is also an explanatory factor: severe need simply causes people to loot.

2. Some people have looted property that was about to be destroyed anyway by the rising water. That doesn't mean that they have a moral right to keep the goods for themselves. But it is both a mitigating and an explanatory factor.

3. People are more likely to steal when other people are stealing as well. If you are the only one committing blatant theft, then you will probably get in trouble. But if everyone else is stealing, then you won't pay a penalty for joining in, and that certainly makes theft more tempting. Besides, if the property is about to be stolen by others, then you will make no difference by taking it yourself. (It's like the situation in which property is about to be destroyed by water; see above). This excuse doesn't justify theft. You should do what is right, not what everyone else is doing. But I believe it's a mitigating factor because the temptation to steal is greater when it's what everyone else is doing.

When I was in college in New Haven, I was waiting one evening on a long line at a convenience store. The lights went out--only in the store, as I recall. You could still see perfectly well. Nevertheless, most people on line took what they had been waiting to purchase, plus a few extra items from nearby shelves, and walked right out. The loss of electric light was a signal that the law was gone: other people were about to steal, so most people joined in. (For enthusiasts of rational-choice theory, this was a Prisoner's Dilemma, and the darkness transmitted a message that enabled people to "cooperate" by looting.)

4. New Orleans may have a weak civic culture, manifested in low levels of trust for other citizens and for institutions. I doubt that many cities could avoid looting under the current circumstances--this must be the worst US natural disaster since San Francisco in 1906. But I do think that a strong civic culture helps when the veneer of civilization is removed, and a weak one hurts. In New York City, the 1965 power failure "was largely characterized by cooperation and good cheer," the blackout in 1977 was "defined by widespread looting and arson," and the latest one in 2003 was again peaceful (sources). These changes track the decline and then the recovery of trust and civility in New York City.

I can't prove that New Orleans has low trust and deep social divisions. The Social Capital Benchmark Survey collected data from Baton Rouge (which scored pretty well), but not the Big Easy. However, New Orleans, for all its charms, has a reputation for high crime, racial division and exclusion, corrupt and violent police, and poorly performing schools. Those problems tend to accompany low trust; and a lack of trust makes people less likely to cooperate when the law disappears.

permanent link | comments (2) | category: Katrina

September 1, 2005

New Orleans: race and high water

I spent a while this morning trying to juxtapose a good map of race and ethnicity in New Orleans with a satellite map of the flooding there. Actually, the New York Times has an excellent interactive map that does just that. There is a very clear correlation between the areas of deepest water and the highest percentage of African American citizens. This relationship may reflect the fact that White people are able to afford to live on higher ground. Or it may reflect more efforts to protect White citizens from flooding. Or it may be sheer chance. But it's part of the story. See also Kieran Healy on Crooked Timber.

I once wrote an appreciation of New Orleans for this blog that I'd like to cite again.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: Katrina