January 28, 2010

our work with games

I begin with the philosophical premise that we should treat young people as actual citizens, capable of doing actual public work and politics. I don't begin with great enthusiasm for simulations or play-citizenship. On the other hand, there is evidence that real youth-led civic projects often lower kids' sense of "efficacy"---their belief that they can make a difference. My friends Joe Kahne and Joel Westheimer reviewed ten excellent programs--mostly focused on low-income students--and found that students' efficacy tended to fall.

The reason seems clear enough to me. Gather a group of 14-year-olds, tell them to identify a problem that is important to them, and give them a few hours a week to work on it. They will begin with a typical adolescent American sense of optimism--We can make a difference!--and will end in disappointment. The challenge is worse if they are poor. Suburban kids may choose something like traffic congestion in the school parking lot as their problem, come up with a great idea, and get thanks from their principal for their excellent thinking. Inner-city kids may choose homicide, homelessness, AIDS, or racism as their problem--and end in frustration.

So we are experimenting with curricula that mix realistic simulations with real-world work. We draw on David Williamson Shaffer's concept of epistemic games: enjoyable, computer-based simulations of adult roles. We are interested less in simulating fancy adult jobs (like ambassador to the UN) than in allowing kids to play roles that are actually accessible to them. The idea is to create a realistic but controlled context in which they can make a difference and learn concrete skills and knowledge. Playing the game takes them off the computer screen, because they must hold face-to-face team meetings, conduct research on their real communities, interview actual adults, and make final "live" presentations.

With our colleagues at University of Wisconsin, we have tested a pilot version of a game called Legislative Aide. A high school class simulates the role of staff to a fictional US Congresswoman who represents their real district. They go to a computer lab that becomes her district office. They receive emails from fictional characters who are senior Washington staff for the politician. They can also email each other. They are asked to interview real adults and develop an action plan for the Congresswoman. When the simulation is complete, they can do some real-world tasks that are part of the action plan.

We are applying to develop a similar game in which the class simulates the staff of a fictional environmental nonprofit with an EPA grant. In this game, scientific knowledge and skills are emphasized.

We have also helped write two applications to the MacArthur Foundation's Digital Media and Learning Competition. They are for two versions of urban planning games. In both cases, the goal is to get teenagers around Somerville, MA to simulate the role of urban planners who are considering the momentous change that is about to hit their real city: the extension of the Green Line subway service. We hope that playing the game will not only teach the individual kids useful skills and concepts; it will also yield data about youth needs and priorities that can be transmitted to real planners and community activists.

The MacArthur grant competition includes a stage that invites public comments on applications. Please visit ours and comment.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: Internet and public issues , a high school civics class

May 18, 2009

Legislative Aide: a civics simulation

I haven't yet blogged about one of our significant activities this spring. We've helped partners at the University of Wisconsin to develop a game or simulation for teaching civics in high schools. Students play the roles of aides in a fictitious US Representative's district office. They receive emails from senior staff asking them to take various steps in researching a local problem and developing solutions. At the heart of the simulation is the same mapping software that we are using in Boston with college students. It represents the mind of a community organizer or civic leader, who views local civil society as a working network of people, organizations, and issues. Our game combines fiction (the imaginary legislative office) with reality (actual issues and real interviews with community leaders, who are sources of information).

We have been pilot-testing the software and curriculum--called Legislative Aide--in schools in Tampa, Florida (which explains my occasional visits down there). This movie provides an overview:

Legislative Aide from Jen Scott Curwood on Vimeo.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: Boston-area social network , a high school civics class

December 12, 2008

a game for teaching civics

(Tampa, FL) I have come down here to begin training high school teachers to use a new software package that we call "The Legislative Aide Game." Students in social studies classes here will log onto a web site that treats them as interns in a fictitious Tampa-area legislator's office. They will put a real biography on the legislator's web page and start to receive emails with assignments from the legislator's staff. These assignments will ask them to study an issue in the real community of Tampa. They will do some initial reading and web research, and then they will start using the same software that we have implemented with college students in Boston. They will generate network maps of people, organizations, and issues relevant to their overall topic. They will interview the people they have put on the map and store the information they learn in nodes. The map will help them to identify "levers"--people, organizations, and networks that are in a position to make a difference on the assigned issue. The students will conclude by writing and presenting an action plan that takes advantage of the "change levers" of the community. Although they don't have to perform a service or action project in the real world to complete our curriculum, that would be a natural next step.

The teachers I met with this afternoon seemed fairly excited about the project, which will begin in January.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: a high school civics class

April 10, 2008

guest blogger: Diana Hess

Diana Hess is a professor of education at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the leading expert on all the complex issues that arise when controversial issues are discussed in classrooms. I asked her to contribute an essay for this blog about a fascinating, moving, but ethically troubling video recently shot in a Bronx high school. She writes:

Last week I received an e-mail from Michelle Obama urging me to view a video of high school students in Jackson Shafer’s class at the Bronx High School for Performing Arts and Stagecraft. I watched it immediately because I am interested in hearing what high school students have to say about the campaign and the candidates--and I was so fascinated that I then watched it again. I forwarded it to some colleagues in civic education with this message: "First, what is it about Obama that these kids find so inspiring--why is he able to tap into this hopefulness when others are not? Second, what would it be like to be a Clinton or McCain supporter in this classroom--is this teacher just wisely making use of a teachable moment, or is he sending the message that the election is a question for which there is a right answer? Third, how much fun it would be to be teaching these kids!"

The next day I read a number of newspaper articles about the controversy that the video sparked. It seems that there is a New York City Board of Education policy that prohibits using students for partisan or promotional purposes. Because the video was on the official campaign website it gave the impression that the students (and perhaps the teacher and even the school) were officially supporting Senator Obama's candidacy. Moreover, in the same message from Michelle Obama, there was a request for donations, which made it appear that the students were being used to raise money, a fact that Mr. Shafer reported not knowing about in advance. There is talk of putting an official letter of reprimand in the principal’s personnel file. I find it astonishing that the Obama campaign would send a staff member into a public high school to shoot video of minors without obtaining required permission (which, it seems clear, would have been impossible to obtain given the policy). That being said, the video does provide an interesting snapshot of how some young people are responding to Senator Obama's campaign, and also raises hard questions about how a teacher can tap into students' enthusiasm for a political candidate without creating an environment that compromises democratic principles.

Although newspaper articles about the video report that Mr. Shafer is an Obama supporter, the video does not show him saying anything explicit about his own political preference. He does show his students the video of the now famous speech about race relations in the US, and the students develop and deliver personal "Yes We Can" speeches during class time, speeches that I found incredibly interesting, moving, and hopeful. One of the students reported talking with Mr. Shafer before school started on days following a primary about how Obama had fared.

It is always dangerous to make judgments about what is happening in a classroom without having a more complete picture--we do not know whether the students came up with the idea to create "Yes We Can" speeches or whether that was an assignment that Mr. Shafer created. And we do not know if Mr. Shafer has provided opportunities for students who do not support Senator Obama’s candidacy to voice their opinions. We do not even know what subject this class focuses on--is it social studies? English? But let's imagine for the sake of argument that the 13 minute video is representative of what is happening in the class writ large. That being the case, what judgments could we make about what is going on here?

First, Mr. Shafer seems like an effective and committed teacher who is willing to ask his students to discuss the very issues of race and how it impacts their lives that we know many teachers shy away from. One student reported that after talking about racism in the class, she began chastising her friends for using racial epithets in conversation--and it seemed to be working. Her friends now say "dude" instead of using epithets. While I have heard from a number of high school teachers that this primary has sparked a level of engagement from the students that they have not seen in past presidential primary election seasons, the students in Mr. Shafer’s class seem exceptionally engaged generally--and remarkably engaged in the elections specifically. The primary is causing them to pay attention to the news. As one student commented, "I never knew what channel CNN was, now I know all the channels."

Second, the students who speak in the video seem to assume that their opinions about Senator Obama are shared by all of their classmates. As an Obama supporter myself, the partisan part of me was happy to witness how his campaign is touching these young people. But as a teacher, I am of two minds about whether what is happening in this classroom should be lauded or criticized. Providing the students an opportunity to talk about race and how it impacts their lives is clearly important and rare. If Mr. Shafer is using Senator Obama's campaign as a lever to promote these conversations, then it may simply be the case of a teacher knowing his students well enough that he can tap into their interests to provoke important learning.

On the other hand, I find it hard to believe that all the students in the class are Obama supporters. Keep in mind that Senator Clinton won the New York primary, and even though she lost the youth vote overall, there were still substantial numbers of young people who supported her then and most likely still do now. It is also likely that some students in the school support Senator McCain, or don't know which candidate they support yet. And even if all the students in the class support Senator Obama, do we really want public high school classrooms to turn into de facto campaign events? I think not-- because the presidential campaign is actually one of many mega controversial issues--and like other such issues, our job as teachers is to promote the consideration of multiple and competing perspectives.

It is not always clear the best way to accomplish this goal. In some instances, teachers may have to give more weight to a particular perspective to counterbalance the majority in order to ensure that controversial issues do not turn into questions for which students think there is only one answer. And teachers need to be careful not to throw out the baby with the bathwater--which could happen if students are not allowed to voice their genuine and authentic perspectives on issues in the interest of "balance."

It is hard to tell from this video whether Mr. Shafer is being sufficiently attentive to the fact that the campaign should be treated as a controversial issue. But if attention is not being afforded the other candidates, and if Senator Obama is put forward as an icon instead of a candidate, then not only has a line been crossed, but an opportunity has been lost. For Mr. Shafer appears to be a strong teacher who has the respect of his students, and the students are amazing--sharp, engaged, spirited, and fun. The class has loads of diversity, including racial, ethnic, linguistic, and gender. And my guess is that there is lots of ideological diversity in the class as well. Thus, we have all the ingredients for exceptionally high quality democratic education: a strong teacher, engaged students, and diversity. Engaging students in deliberation about highly controversial issues, like the presidential campaign, in such an environment is an opportunity that is too powerful to waste.

permanent link | comments (1) | category: a high school civics class

July 27, 2007

teens address school reform

On Wednesday night, we finished our summer program for 13 kids, ages 12-14. They built a website on issues in the Prince George's County (MD) school system, which they attend. Their site is part of the Prince George's Information Commons, which we have been building--slowly and sporadically--since about 2002.

We did almost all of the computer work, but the kids developed the site plan and wrote virtually all of the text. They chose all but a few of the audio clips that are scattered through the site; and they were completely responsible for the interviews that generated those clips in the first place. We will now work with colleagues at the University of Wisconsin to develop software that will help students to build their own sites for community research--removing people like us as technical intermediaries.

We now need to figure out what we learned from the summer's experience. I haven't had a chance to reflect enough, but I think we learned that: Group interviews of activists and officials provide great educational opportunities. ... It's hard to present a website to a live audience, as our kids tried to do on Wednesday night when their parents and others adults gathered to see their work. ... Kids have a hard time imagining that their work will have any public impact--although I think it could have an impact if the project is well planned and disseminated. ... Kids are experts on certain aspects of their own world, such as discipline issues in their schools. Adults will (rightly) defer to their expertise. ... Children's behavior is very dependent on context. Give 13 young teens an opportunity to interview a public official in her office, and they will act like 40-year-olds. They will discuss issues such as truancy and vandalism with great maturity. Yet we know that some of the same kids have had their own discipline problems.

For me, as a proponent of positive youth development, the program was both inspiring and sobering. It was sobering because the youth and their interviewees so often identified student misbehavior as a major issue in their schools--a key barrier to learning. Those of us who talk about youth as assets don't often emphasize teenagers as dangerous and self-destructive. Yet the program was inspiring because it showed how well teens respond when they are taken seriously.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: a high school civics class

July 5, 2007

discipline

This is our mapping team, busily studying the school system of Prince George's County, MD, which they attend. Today, they interviewed an impressive and helpful state delegate.  She thought the biggest problem in schools is discipline, because that's what drives teachers out of the profession and disrupts classrooms so that kids can't learn. Indeed, all members of our team raised their hands to say that their classrooms are often disrupted. Security guards come to remove students hundreds of times each year.

She thought the biggest problem in schools is discipline, because that's what drives teachers out of the profession and disrupts classrooms so that kids can't learn. Indeed, all members of our team raised their hands to say that their classrooms are often disrupted. Security guards come to remove students hundreds of times each year.

Of course, naming the fundamental problem as "discipline" doesn't solve it. Some kids are disruptive--the question is what to do about that. If one in one hundred children were out of control, you could remove those few and give them special services. But I suspect the rate is quite a bit higher than that.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: a high school civics class

June 29, 2007

trajectories

We've been meeting intensively this week with teens from Prince George's County, MD. We've had 14 hours of class since Tuesday afternoon. All our students happen to be African-American, but they are extremely diverse (as I would have expected). Consider these statements that two of them wrote yesterday:

1. I am a young black African American male I attend -- High School although it is not the best school in the world It still ofers some what of a education. Right now at this point in my life I am trying to get back on the right track study more and stop hanging out with the friends I have that I know won't go anywhere in life based on there action. I am also trying to do better next year than I did this one so when the time comes I can go to college.

2. Hello! My name is Marcus [pseudonym]. I am officially a freshman at -- High School ... . I love to play sports. I joined this program because I was interested in the summary I was given. In my spare time I like to play video games, read, play sports and watch movies. When I grow up I would hope to be a physician. In conclusion, you can see I am just an average teen that would like to make a difference against modern day issues that face young people such as graduation rates, cleanliness of schools, bullying, education, Racism, and the increasing rate of lunch prices. Well, I'm done now, and remember, 1 person can make a difference.

Marcus's father is a graduate of University of Maryland. Note his confidence, his good writing, his general optimism and outwardness. His classmate (quoted first) is much less confident and much more challenged. His brother was murdered, and he's had other trials.

I walked around campus with both of these young men. I'm sure that Marcus was intrigued by the place and felt pretty much at home there. I hope that his classmate, who was much quieter on our tour, could see some realistic connection to the University and didn't find it overwhelming or alienating.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: a high school civics class

June 22, 2007

youth mapping

(Milwaukee) Next week, we start an intensive program for teenagers in Prince George's County, MD who will choose an issue, conduct interviews of relevant adults, and depict the results in the form of maps and diagrams. We will be testing software that's being designed by our colleagues at the University of Wisconsin. Our goal is to develop and refine a software package that will easily add an element of research to service-learning programs, as kids identify assets, relationships, and sources of power and thereby make their civic work more effective.

Near the beginning of the first day, I want to show the kids great products that their peers around the country have created. Students at Central High School in Providence have built a multimedia website about their own school that's pretty absorbing. I can find good youth-produced videos, like the ones collected on What Kids Can Do. I've personally worked with kids to create a "commons" website for Prince George's County that has some video, audio, text, and maps. My organization, CIRCLE, has funded kids in Tacoma, WA to create this interesting documentary on teen pregnancy. We've also funded other youth-led, community-based research projects. They are listed here, although some don't yet have public products.

We want our team this summer mainly to work with maps and diagrams, perhaps illustrated with some video and audio footage. Although "mapping" is a common activity for youth today, I can find few youth-produced maps online that might inspire our team. In one sense, this is good news--we feel that we're doing something significant by creating templates for more exciting map projects. On the other hand, I'm sure there are good products out there, and I would like our team of kids to see them.

permanent link | comments (2) | category: a high school civics class

March 2, 2007

history and race as seen by young and old

An article in yesterday's Washington Post begins, "Ask older residents of historic North Brentwood their recollections of the town, and they go into a reverie about kids playing house-to-house and about how the town was self-contained with businesses and shops. Mostly, it was black, and the generations who had lived there gave the place its essence. But 'change comes,' said Eleanor Traynham, 71, who was born and raised in the town, in Prince George's County, and returned in 1992. And 'you have to be able to adapt to change.'"

North Brentwood is part of the urban core of Washington, DC but located across the state line in Maryland. It was founded by and for African Americans in the days of legal segregation. It is now a major arrival point for Latino immigrants.

It so happens that a high school class and I interviewed the same Ms. Traynham in 2003. Some colleagues and I had organized a program in which the students used oral history to reconstruct the history of their own school, Northwestern in Hyattsville, which had gone from de jure white, to integrated, to de facto African American and Latino over five decades. The class created an interactive website to present their findings and provoke discussion. You will see that both the students and their African American informants were ambivalent about state-sponsored integration.

I have pasted our class notes from Ms. Traynham's interview below the fold, because they represent a fascinating record of local history--and an example of the good questions that contemporary kids come up with.

Eleanor Thomas Traynham

(Community activist and retired Postal Service Employe . Graduated the all-Black Fairmont Heights HS in 1953. Sister of Bill Thomas [whom we also interviewed]. Interviewed on January 8, 2003 at Northwestern High School.)

I was born in North Brentwood in Prince George’s County and raised long before integration. I grew up when there were only two high schools in the County for African American students. To go to junior high school I had to catch a bus and ride a long way to Lakeland Junior High School, past many schools that were for white children only. Fairmont Heights--a new high school for black students--opened in September of 1950 and I graduated from there in 1953. I attended Bowie State--it was then Bowie Teachers’ College--for 2 years, but decided I didn’t want to be a teacher. The little kids were often spoiled and the older kids thought they knew everything, and I decided maybe I didn’t have enough patience to manage other people’s children.

I brought this book African American Heritage Survey (1996, about Prince George’s County) because I thought you may want to see which has pictures of the schools I attended. In 1949, the school was a wood building, later it was remade in brick.

When I was in school, there was no talk of integration at all. … I had to ride the bus from North Brentwood to College Park to a little school called Lakeland. When Fairmont Heights opened, it was a long ride but it was a beautiful high school. We had to ride all the way there, but we didn’t mind it.

My younger brother and sister came up just as integration arrived. I have a brother who was the first African American here at Northwestern. My sister also was among the first to integrate Mount Rainier Junior School. By the time they went to integrated schools, I had already graduated. My brother was very independent, and after he graduated high school he went to University of Maryland and was one of very few African Americans, and received a degree in Chemical Engineering in four years. It was not an easy task. There were a lot of mean spirited people, although I don’t believe people are born with this kind of hatred in their hearts. They learn it.

The children in the community taunted my brother and sister, saying they were trying to be better than everybody else by going to these white schools. But my siblings stood up to whatever anybody might say, because my mother had instilled in them that education was the most important thing. Eventually after two years my sister caved in and transferred to go to high school with the rest of the kids at North Brentwood, and did just fine.

When I was in school, I was not aware of the fact that the students in the Black schools got the second-class books and materials. I had my older brother’s books and I just figured you received hand-me-down books. I was not aware we got old white school books until years later. But, I think it’s not good to dwell on these things. They happened. Lots of young people did well even with older materials. I think it’s how you apply yourself.

What do you think about segregation in retrospect?

When I was in school, we had real dedicated teachers who took a great interest in young people. I remember a teacher who always talked to us about Hampton University which she loved, and told us great stories about life at Hampton University so we would be inspired. In college, I went to school with lots of people who were not dedicated teachers, and lots of people I wouldn’t want teaching my kids. Between the time I left Bowie and the time my baby sister went – there was an 18 year difference between us – it was different. And now some teachers are more dedicated than others. School is a lot different now. But, I still maintain that you have to put something into it to get something out of it—whatever you do. I got good grades, although it was a bit difficult in college because my mother wasn’t there to keep me going. After I decided that teaching wasn’t for me, I got a job in the Postal Service.

I worked for the US Postal Service for 30 years and 10 months, in the customer-service branch. One thing I learned there is that no matter how they humiliate you, the customer is always right.

How do you feel personally? Do you feel like white Americans stole a piece of your life, a piece of your history?

I don’t personally feel that way. … I have watched movies about how people were treated in the South, and it hurts me, but you can’t live with hatred in your heart. … Hatred is a thing that sort of makes you old and tired, I think. Not all people are bad, and there were a lot of whites who worked with us and for us-- going all the way back to the Underground Railroad. And there are some Blacks who will try to hold you back. So you will end up hating all colors and races. We were dealt a low blow, but lots of us have been successful. There are so many African Americans we can be proud of -- too many we only hear about during Black History Month.

What do you think happened to the African heritage that’s been lost, and have you done anything to bring it back?

I am one of the people on the African American Heritage Museum project. We did an oral history project. My family has traced our ancestry back to certain slaves in Anne Arundel County who had come from Africa. A lot of us don’t know anything about our African heritage. But, there are a lot of people who are ashamed because of what they saw in movies and on TV [about Africa], but that is because they don’t read, haven’t gone to museums and don’t study other cultures. My mother always stressed the importance of reading. She only went to school through the 8th grade, but was one of the smartest people I know. She was one of ten kids, and needed to help. She worked in a white family’s house and learned all she knew by reading books in their house. I also work with the Community Center in North Brentwood to try to bring culture from many countries to the Center. We’ve brought African singers and dancers, and also performers from Mexico and Taiwan. I am working with the Gateway Community Development Corporation, which has instigated an Arts District in the four cities along Route 1, and they have brought a lot of artists. I also work on a share food program and with the Historical Society. I used to be very involved with the church also, but not as much anymore.

Did you ever get harsh comments or racial comments growing up?

Yes. Not in school, but our community was next to a white community, and there was a Sanitary Supermarket - later became a Safeway - on 34th in Mt. Rainier. We’d have to walk through the white community to get to it. One night at dusk my friends and I met up with a group of men who warned me: “Nigger don’t let me catch you here after dark.” And we never went there after dark. Some would let their dogs out to chase us. The boys in our community would be chased out of the white community at any time of day. But the same thing happens today, and it’s not always a “racial thing”—sometimes it’s a “clannish” thing. We also had it. If the black boys from DC came up to date girls in North Brentwood, our boys would chase them out.

What was your reaction to the name calling?

I think I was scared to death and I needed to get out of there as soon as possible. But, I was mainly a very happy child growing up and I didn’t hold grudges or anything.

How did you feel about Brown v the Board of Education?

From what I remember, it was a very frightening thing, to see kids have to go to school with the National Guard. You’d see the violence, and I’d say these kids should just go back to where they came, and not risk it. But, I was already out of school at that time. I remember my younger sister being terrified, but I will let her tell her own story when she comes to see you.

Was it hard to get a job?

It was difficult getting a job. I was a big girl and so I was up against two hard things – my color and my size. I couldn’t waitress or work behind a counter because they would say there wasn’t enough room. When Prince George’s Plaza first opened I got a job at Hot Shops as a vegetable cook. Then I passed the Post Office exam, and I went and worked there.

Was your mom making decisions on her own or were other parents in favor of integration too?

Not a lot of people that I knew of in our community felt that integration would equal a better education. My mother sometimes thought that our schools were second class. I don’t know if there were other people in our community who also felt that way. In the long run, in all instances, desegregation was not a better thing.

Would you have desegregated the schools, if you had been in charge of the school system?

I probably would have kept them segregated, and I would have demanded that the Black schools be given equal funding. I think that the teachers I had in the segregated schools were much more dedicated than some of the teachers I have seen since, and most of the Black teachers that I know would have preferred to stay in the Black schools.

Do you think segregation still exists in some form, like financially or in terms of Fairfax County vs. Prince George’s County?

There is still financial segregation, and I can see it in changes in the opportunities offered to Prince George’s County students. When I was young, we used to take field trips to the Smithsonian and now there’s no money and no buses for such things. The buses are being used to drive students all day long back and forth from home to school.

What do you think can be done to improve schools?

Parents used to work a lot more with their kids. If the parents don’t work with their children at home, it just doesn’t work. You need the support of parents. Also, if a teacher knows the parent is supporting them, they teach better. But, right now there are no parents in the PTA. There needs to be more money for the schools and smaller class sizes, but in order to get smaller classes you need the money. I’ve kept hoping that Prince George’s County would get more money to dedicate to education, but it’s just not happening, and won’t especially now with the State’s money crisis.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: a high school civics class

February 13, 2007

youth mapping this summer

This summer, my colleagues and I will help run a pilot course for adolescents in Prince George's County, MD. We will teach these young people to identify issues or problems that they want to address, and then "map" the networks of groups and individuals that could make a difference. They will document their work for public display, although we haven't decided what medium they should use: their art works, audio recordings, audio plus still photos, or video.

Along with colleagues at the University of Wisconsin, we have submitted a large grant proposal that would allow us to develop and pilot elaborate software for such courses. This software would allow teenagers to make diagrams of local social networks, much like the "network maps" that are popular in sociology today. However, our community partners cannot wait to find out if we get money for software-development. Therefore, we have committed to teach the pilot courses whatever happens, if necessary using old-fashioned tools like magic markers and poster board.

Two of the essential principles are: youth voice (students should be assisted in developing their own agenda and analysis, without presuppositions from us) and a particular understanding of power. "Power" will be defined not merely as official authority (like that of a mayor or a school principal) but also the capacity of ordinary residents to make a difference by working together. That is why we will help youth to map local networks of citizens.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: a high school civics class

August 17, 2006

a learning community experiment

I'm interested in the following ideas and I'm thinking about a true experiment that could help to test them:

1. Education is not just what happens to kids inside schools. A whole community should be involved in educating all of its residents. Standard educational measures (such as test scores and school completion) will improve to the degree that many people in many venues participate in education and do not leave the job to professionals in schools.

2. Kids benefit from being offered opportunities to serve their communities. They are more likely to succeed in school and less likely to engage in self-destructive behavior if communities tap their energy, creativity, and knowledge for constructive purposes.

3. A rewarding and effective form of service is to catalog the assets of a community and make them more available to residents. All communities, no matter how economically poor, have assets worth finding. When communities know their own assets, they can address their own problems better and take better advantage of outside support.

Therefore,

4. It is a promising idea to help youth to identify opportunities for learning in their communities and to make these resources available to their fellow citizens.

We're cooking up an experiment in which kids would be assisted in identifying skills and knowledge that other residents want to learn. The kids would then find opportunities for learning--formal courses and classes; educational institutions such as museums, parks, and libraries; individuals and companies that sell training; jobs with educational value; and residents who are willing to share knowledge free of charge. This project would resemble the St. Paul Neighborhood Learning Community.

Kids would enter the information in a database so that other residents could find learning opportunities on a map or by searching by topic. Some local community centers would be randomly selected to participate in the data-collection; others would not; and we would survey kids and adult volunteers in all the centers to measure the effects of participating. We would hypothesize that, in the participating centers, there would be a greater increase in measures of: academic success, understanding of community, and interest in civic participation.

permanent link | comments (1) | category: a high school civics class

July 26, 2005

youth-led research on obesity and immigration

There is a cool new movie on the Prince George's Information Commons website that students created as part of a project that I directed. You can click here to view it, but first, some background ....

More than a year ago, we received a grant from the National Geographic Foundation to help high school students study the "geographical causes of obesity." There is an obesity epidemic that's costing lives and that's especially concentrated among adolescents of color; and our students at Northwestern High School were concerned about it. Our idea was to look for causes in the local landscape--in addition to more familiar factors like corporate advertising. This focus seemed promising for two reasons. First, young people might be able to do something about local land-use (and learn political skills in the process), whereas fast-food advertising campaigns are fairly intractable. Second, the literature suggests that local factors do matter. Having connected and well-lit sidewalks encourages walking. Having affordable, convenient sources of fresh produce encourages healthier eating; and so on. We happen to work in an area that is consistently low- to moderate-income, but the development pattern differs dramatically from block to block. Some places are suburban subdivisions; others look like part of a traditional city. So we hoped to explain the variation in food consumption and exercise patterns as a function of street layouts and other land-use patterns. And we hoped to do that as youth-led research, with high school students in charge.

This was too hard. The students did collect some data, but it was very equivocal, incomplete, and imperfect. Therefore, after several changes of course, we focused on a different intersection between geography and nutrition. Northwestern High School has a very large immigrant population, along with African American students who have typically migrated to Maryland from the South via DC. We thought we would investigate the way that food and exercise changed as families moved here from far away.

After many months of work, our student team has created a flash movie to capture their main findings. (They left much information on the cutting-room floor, but culled some highlights for a short video.) Their product is exciting for me, because I was present when all the audio and other data were collected, but I had nothing to do with creating the movie itself. I see some mistakes that need to be corrected sooner or later, but overall, I like it a lot.

permanent link | comments (1) | category: a high school civics class

February 17, 2005

the latest on our local work

For the last year, with generous support from the National Geographic Foundation, my colleagues and I have been working with high school kids to study the environmental causes of obesity in their community and display the results on public maps on the Prince George's Information Commons website. It has been a tortuous process, frequently derailed by changes in the school's administration and rules, flawed ideas and plans on my part, turnover among the University of Maryland team, attrition of students, and technical problems. In the latest phase, the kids have been trying to present their ideas in the form of audio segments, mixing voice and music. But the talented graduate student who was helping them had to quit this week for health reasons.

Despite all these problems, various groups of high school and college students with whom I have been working should have produced more than 30 separate research projects on various aspects of their community by the end of this summer. I am starting to envision the Commons website as a kind of magazine about Prince George's County, with "articles" in various formats (including audio and video) and lots of opportunities for readers to post comments. Blogging software like MovableType could underlie the whole site, although it wouldn't look or "feel" like a blog. After all, blogging software is essentially a database that displays selected entries on a website. So the Prince George's Information Commons could consist of a database of research products created by a wide range of students and adult volunteers. The homepage would present short summaries of some recent products, with links to the full results. Each summary could be accompanied by an enticing picture to draw visitors' interest.

Prince George's County is a large jurisdiction (pop. 838,000) without its own news media. It receives generally disparaging treatment from the Washington press corps, probably because it's the suburban county with the lowest income and the largest African American population (62.7%). I didn't get involved in these projects to try to create a news organ for the community, but that wouldn't be a bad thing.

permanent link | comments (1) | category: a high school civics class

January 17, 2005

kids' voices

I spent today listening to kids--16 boisterous, funny adolescents from the nearby high school. We had recruited them to talk about their experiences as immigrants (or migrants), and how their eating habits had changed as they had moved to Maryland from West Africa, Central America, the West Indies, the Philippines, or Washington, DC. We taped the whole day so that a smaller group of volunteer students will be able to shape the best parts into an audio documentary on immigration and food. This is the latest stage of our National Geographic project on nutrition.

The parts of the discussion that will find their way into the documentary will be about recipes, memories of meals, shopping and cooking, and health concerns. For today's blog, I'd like to report on a different topic, a digression. Most of the immigrant kids agreed with one who said: "Living in St. Lucia, I thought [the US] was the great land of opportunity. I never thought it was heaven, like some people do; but if you work hard, you can achieve anything." (This is a close paraphrase, not a precise quote). When an adult asked if the kids thought that poverty came from laziness, they resisted that thesis, but they kept coming back to it. "If you really want to get something, you can do it. There was a homeless person who went to Harvard." They acknowledged that there were insurmountable barriers to economic success back in their home countries--for example, the tuition required to attend elementary school. But in the US, success "depends on a person's drive."

The same theme of self-reliance and personal responsibility returned when they discussed fast food. "It's your responsibility what you eat. After all that healthy food back home, you see a big hunk of meat [at McDonalds], you know it's gotta be bad for you." One young woman said that advertising could influence people to eat fast food. "Yeah, but that's your fault cause you can't control yourself."

A student from Cote D'Ivoire said that back home, people viewed African Americans as lazy, and white Americans as "slave-drivers." She said, "I don't think America is that great of a place, but I do think freedom of speech and freedom of religion--a lot of places don't have that."

permanent link | comments (0) | category: a high school civics class

December 1, 2004

youth research as civic education

Today, I�ll be working with two groups of young people who are involved in community research: my undergraduate �Leaders for Tomorrow� (who are still in the planning stages of their project), and high school students who are taping interviews with community residents for a radio show. In general, I�m enthusiastic about community research and �youth-led research� as forms of civic education. In community research, students study their social environment, collecting and analyzing data under the leadership of a teacher or other adult. In youth-led research, students choose their own issues and questions and design their methodology, with appropriate guidance from adults.

Such projects are reasonably common in schools and youth organizations such as 4H. However, I don�t know many curricula or teachers� guides for community research or youth-led research. Instead, each project is unique and requires heavy investment by a talented teacher or a very well organized and prepared group of kids. To make community research easier, I can imagine a guide and an interactive website that helped classes and youth groups to conduct assignments like the following:

student research and service-learning

Although student research needn�t be an alternative or competitor to service-learning, it�s worth considering the relative advantages of each. Service-learning means a combination of community service with reflection, writing, and sometimes research on the same social issue. It is very common today (present in as many as 40% of schools), and it can be a great civic pedagogy. Indeed, it can be a transformative experience for students and teachers alike, developing their skills and confidence, challenging them intellectually, and committing them to serious civic work later in life. However, service-learning often degenerates into cleaning up a park (or even stapling papers in the principal�s office) and then briefly discussing the experience. This happens because it is hard to organize challenging service-learning�as I know from my own, often unsuccessful efforts in the high school. Service-learning also degenerates because it implies and requires strong values, particular ideas of justice and virtue. These values are hard to sustain in pluralistic public schools that have not been formally charged with promoting ideals other than very vague and anodyne ones. Finally, service-learning sometimes degenerates because it is seen as a way to �engage� students who are not doing well in standard classrooms. Given this goal, some teachers avoid assigning intellectually challenging exercises in connection to service.

Research, unlike service, is close to the main academic mission of schools. Yet community research can address public problems and enhance public goods. Thus I think research makes sense, at least as a complement to service-learning.

Incidentally, CIRCLE has funded young people to organize research projects about youth civic engagement. This is the only form of direct work with kids that we may undertake as an organization, because we are a research center with a specific focus (youth civic engagement). The process of selecting youth groups to conduct these projects has taught us a fair amount about what seems to work. We have learned, for example, that student-run surveys of other students aren�t great. The size and quality of the samples is inadequate, so the kids don�t really obtain meaningful results. On the other hand, students can make excellent documentaries and run good focus groups.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: a high school civics class

November 24, 2004

progress toward an information commons

Since 2002, some colleagues and I have been working slowly to create an "information commons" for Prince George's County, MD. A real information commons would be a voluntary association devoted to creating public goods and putting them online. These goods might include maps, oral histories, historical archives, news articles, discussion forums, research reports, calendars, and directories. If community groups preferred to maintain separate websites, they could link to features on the commons site and thus "distribute" the commons across the web. The association would also lobby locally on issues like the "digital divide" and broadband access; and would provide training and support. Information commons in various communities would form networks and share software.

So far, the tangible products of the Prince George's Information Commons are a modest website whose best feature is an oral history, and a series of articles defending the concept of a commons.

We decided not to start by creating an association, because we were afraid that community people wouldn't see the need for such a body or the advantages of joining. Instead, we hoped to create enough exciting and useful content on one site that it would draw traffic and interest. We would then ask participants if they wanted to "own" the site formally by creating a non-profit governing board.

Progress has been slow for two main reasons.

First, we have chosen to work with high school students, and for the most part ones who are not currently on the college track. This has been extremely rewarding work, but it's also a relatively slow way to generate exciting content. For instance, students spent a whole summer gathering excellent audio recordings that documented immigration into the County, but we haven't figured out how to use that material online. It sits on a CD. Likewise, the kids took a very long time collecting information for "asset maps," and the result was a relatively small set of incomplete (and now dated) maps.

Despite the slowness of this approach, I intend to continue to invest the majority of my discretionary time in the high school, because I find it extremely satisfying to work directly with kids.

The second obstacle is financial. We have had great difficulty raising money for the core concept of an "information commons." Instead, we have raised funds from foundations with specific interests in, for example, history or geography. As a result, we haven't had money or time to develop the commons itself. Instead, we have lurched from one project to another.

Ideally, we would always be busy with three tasks: 1) teaching high school (or middle-school) students to create digital products for the website; 2) working with college classes, churches, and other adult groups to help them to create content; and 3) installing and managing interactive features for the website itself, such as an open blog, a "wiki," or a map that visitors could annotate. These features would have to be carefully monitored or else they would be vulnerable to spammers and cyber-vandals.

To date, we have only had sufficient resources to do the first of these tasks, and that only on a small scale. Recently, I've been thinking hard about the second job: recruiting independent groups to produce their own content. Based on some recent conversations, I am optimistic that by the spring we will have three groups feeding content into the commons site: the high school class, a college class, and possibly a group of teachers.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: Internet and public issues , a high school civics class

October 15, 2004

food for thought

Here is a strange statistical result. My colleagues and I have been teaching

high school students to investigate the causes of obesity in their community--as

a form of civic education. This fall, they are going to conduct and tape interviews

and create a radio show to publicize their results. To give them some data to

work fro

What's going on? Maybe a lot of kids are mistaken or dishonest, but it's strange that the relationship between fast food and body weight would be so linear and negative. The sample is too small for serious statistical analysis, but we noticed that immigrant kids are more likely to eat fast food, yet less likely to be overweight. So maybe immigrants eat good food at home but go out a lot to McDonalds.

There are more possible explanations. For instance, the Washington Post's "Kid's Post" section reported last Wednesday that young people order less healthy food at restaurants like Outback Steakhouse and Red Lobster than they do at fast-food places. So maybe it's good to go to McDonalds if it keeps you from ordering the "surf and turf" at a sit-down restaurant. But most of the kids we surveyed cannot afford regular visits to real restaurants.

In any case, the students' research task is a lot harder because of this result.

permanent link | comments (2) | category: a high school civics class

June 16, 2004

geographic information systems (GIS) in civic ed

Yesterday was our last class at the high school for this academic year. We brought along some maps (based on data that the students had collected) that showed aspects of the community that may affect young residents' health. In particular, the maps show that kids who walk are clustered in certain areas; thus some neighborhoods may be built in ways that are friendly to pedestrians. That would be an important finding, because we know that walking reduces obesity, and obesity is a big health problem. Our students are alert to possible causes of error (the small sample, selection bias, hidden causes, etc). We would have to do a lot more research before we could draw any rigorous conclusions.

Today I took an excellent intermediate-level class on GIS software and became increasingly excited about what we can do with the class when we resume next fall. We'll certainly ask them to collect more data about their fellow students' behavior and locals assets such as stores and parks.

It's exciting to address an issue (obesity) that's usually seen in strictly pyschological terms--as a matter of body-image and will-power--and to look instead for geographical causes. Active citizens can potentially change the local landscape and zoning laws, whereas body-image and eating habits are very hard to change. Meanwhile, GIS software is making it possible for kids who don't have very advanced skills to understand their environment in tremendously powerful ways.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: a high school civics class

June 1, 2004

map work

As regular readers know, my colleagues and I have been helping high school students to conduct fieldwork and make maps of their community. They are trying to understand how features of local geography may affect behaviors that, in turn, affect health. We and the students have collected mountains of data of various kinds: questionnaires, focus group notes, notes from "window tours" of the neighborhood, GIS data collected with Palm Pilots, ratings of local food sources, and more. Most of the data is incomplete and not yet suitable for drawing conclusions. Nevertheless, we need hypotheses so that we can narrow our focus.

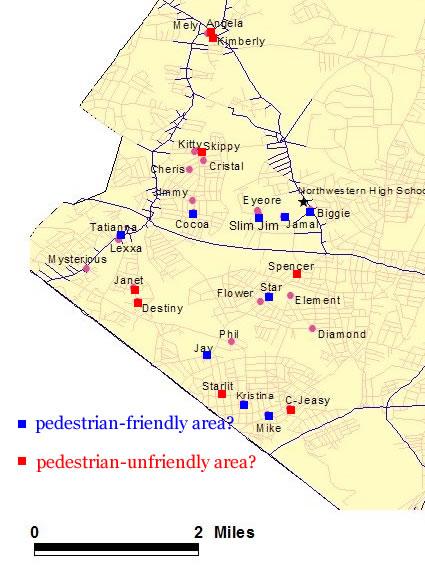

Here's a map, generated from the students' data, that suggests some ideas for our kids to pursue more rigorously. Each name is a pseudonym of a real student in our class.

The blue squares show students who appear to live in pedestrian-friendly areas. They say that they walk for exercise, they report that their neighbors walk a lot, and they say that it's safe to walk near their homes during the day.

The red squares mark students who answered "no" to at least two of the same questions, so they appear to live in pedestrian-unfriendly zones. The remaining dots mark students who gave mixed answers or no answers at all.

The cluster of red squares near the top of the map includes three young women of Caribbean ethnicity who live in single-family homes. Two of them say that it's safe to walk, but none say that they or their neighbors walk. (In general, females in our sample are less likely to report that their neighborhood is safe, but more likely to walk even if they feel unsafe.) The cluster of blue squares near Northwestern includes four African American young people, all apartment-dwellers, who walk and feel that walking is safe and common. There is a positive correlation between being African American and walking, in our small sample.

The real purpose of all this work is civic education--to teach students to understand and care about their communities, by engaging them in real research. This approach to education requires that we take their research questions very seriously ourselves. Although most of the information we have collected so far is simply confusing, I remain hopeful that we and our students can generate truly innovative findings about the effects of urban planning on health.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: a high school civics class

May 12, 2004

making maps

Yesterday, in the late afternoon, I was back on the streets of Hyattsville, MD, mapping the neighborhood by entering data into a Palm Pilot pocket organizer. This week, unlike last, we had a large group of high school students with us, as well as five adults. Even though it was as hot and humid as August, and even though there are no sidewalks on many of the busy roads, we managed to cover some ground and enter a lot of data into our organizers.

We have also collected data on about 50 kids--where they live, what they eat, where they get their food, and how and when they exercise. In addition, we have general Census data on the neighborhood. What we need at this point is a strong research hypothesis about the relationship between urban form and healthy behavior. We could continue collecting street-level data about types of businesses, sidewalk and street safety, and residential housing for years. It has been good to map some areas intensively, because we've learned how to collect and manage data (and how to get kids safely from A to B). But we need to focus on some compelling issue or finding; otherwise, we're going to run out of motivation. Ideally, the kids would come up with this focus. We will certainly consult with them, but we have so little time with them that I'm afraid the adults are going to have to develop the main ideas. As soon as I get some time, I'm going to sift through what we've collected and look for patterns.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: a high school civics class

May 4, 2004

mapping

This afternoon, I was out in West Hyattsville, MD with a Palm Pilot, collecting data on restaurants and sidewalks. The data that we collected will help our high school kids to make maps of the factors that may influence obesity in their community. The kids themselves have been going out weekly with some graduate students. Since the grad students are about to finish their semester, I wanted to learn how the Palm's work so that I (and several colleagues) can take over, starting next week. Unfortunately, on this particular occasion, the adult team outnumbered the high school kids. Life is always chaotic at the school, and you never know how many students will show up. So we adults cheerfully picked up Palms and joined in the data-collection.

I'd love to write something insightful about the commercial strip that we mapped. Any place is interesting if you observe it closely, and this happened to be a solid, working-class district of bodegas, barber shops, speciality stores (and empty lots with gang graffiti) that would provide lots to write about. Unfortunately, my eyes were glued to the screen of the Palm the whole time, so I saw nothing interesting. I did get very efficient at data-entry and rolled through a whole extra block on my own while the high school kids had an ice-cream break.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: a high school civics class

April 6, 2004

kids, computers, and research

I haven't posted lately about our work with high school kids, because I've missed the class for several weeks in a row due to scheduling conflicts. With help from my colleagues and grad students, the kids have explored the issue of obesity, learned some geography skills, and deliberated about what maps they should make that will help explain (or even reduce) the obesity problem in their community. They have decided to select one small area that contains both food sources and exercise opportunities. They will collect data about food quality and price, the exercise options, and the "walkability" of the streets in that area, and then they will make GIS maps for PrinceGeorges.org This will be a pilot study that should lead to the comprehensive mapping of the whole community.

One thing I have learned from this work is that students are not automatically facile with computers just because they were born after the release of Windows 1.0. Many students with whom we have worked have spent little time in front of computers; they have only been taught �keyboarding� in school (this means typing, but with a word processor); and they have fairly low confidence in their own abilities.

The same problems show up on national samples. Analysis of the National Education Longitudinal Study (NELS) by Jianxia Du and James Anderson reveals that consistent use of computers in schools is correlated with higher test scores for White and Asian students and for those who take advanced courses. Presumably, they are using computers to enrich their studies and to do creative, challenging work. But there is no positive correlation for young people in other racial and ethnic groups or for those of any background who take less challenging courses. �Disadvantaged children tend to utilize computers for routine learning activities rather than for intellectually demanding applications.� In fact, students who take computer courses perform worse on standardized tests than other students, ceteris paribus.

Mark Warschauer has compared two schools in Hawaii that intelligently integrate computers into their science courses. In both schools, teams of students use computers to conduct scientific research, guided by teachers from several disciplines. But one school serves an affluent and selected student body, 97% of whom go straight to four-year colleges, while the other serves a neighborhood with a per capita income under $10,000. At the selective private school, teachers have personal experience in graduate-level scientific research. They teach students to collect field data using held-held devices, download the data to computers, and then intensively analyze them (with help from the calculus teacher). Meanwhile, the students at the Title One public school take boats to outdoor locations, learn to grow seaweed, and then use computers to publish a team newsletter.

Both activities are worthwhile; both teach skills and knowledge and engage students in creative teamwork. But there is a fundamental difference in the kinds of skills taught and the overall purpose of the exercise. As Warschauer notes, �One school was producing scholars and the other school was producing workers. And the introduction of computers did absolutely nothing to change the dynamic; in fact, it reinforced it.� Teachers at the public school were very conscious that they needed to give their students the skills demanded by current employers�collaboration, responsibility, and teamwork�whereas the private school tried to place its graduates in demanding college programs where they would be expected to show independence, originality, and sheer intellectual excellence.

It is not easy for teachers to overcome this gap. Many of the students in our project write English at an elementary school level (although they may be bi- or even trilingual) and they have limited skills for searching the Web or reading text. It is hard to move them a long distance in a single course, and hard to set high expectations when their academic self-confidence seems fragile and they are far from achieving pre-college work. There are good reasons simply to teach responsibility and teamwork--attributes that really will help high school graduates in the workplace.

No wonder African American and Hispanic students are most likely to use computers in school for games, for drill and practice, or at best to create simple Websites with text and pictures; whereas White and Asian students are most likely to use them for �simulations and applications" (Wenglinksy, 1998). The "soft bigotry of low expectations" is a real problem, although individual teachers are hard pressed to solve it.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: a high school civics class

March 11, 2004

the politics of obesity

On Monday, I was with 45 high school kids, talking about the causes of obesity. Then the Centers for Disease Control announced that excessive body weight will soon be the leading cause of death in the US; and the House of Representatives passed legislation to shield fast-food restaurants from being sued for causing obesity. (This is the so-called "Cheeseburger Bill.")

I have never made a serious study of nutrition, the politics of food, or body-image and gender. But I can report that the minority adolescents in our project mostly think of obesity in psychological terms. They ask: Do we have enough will-power? Do we know enough about nutrition? Do we have appropriate body-image? What are the effects of the entertainment media on our health?

Meanwhile, some research shows that our geographical environment affects our body weight. Connected sidewalks help by encouraging exercise; convenient grocery stores increase the odds that people will cook vegetables; and so on. In our project, we are drawing kids' attention to these factors instead of the strictly psychological ones. Originally, this was simply because we wanted to teach geography--and you can't make maps of body-image or TV ads. However, I'm starting to think that we are making a radical move. Our project will locate the cause of weight gain outside of kids' heads and bodies, in the local community--and it will suggest that adolescents can understand and change where they live. In other words, this approach could be very empowering.

I have the same ambivalent view of the "Cheeseburger Bill" as Calpundit. He says:

On the one hand, I don't think much of using civil damage suits aimed at a specific industry as a way of changing social policy. Down that road lies madness.But at the same time, I also don't think much of Congress exempting specific industries from the civil justice system. That can lead to some madness of its own.

Those in favor of the "Cheeseburger Bill" say that we should be personally responsible for our behavior; eating too much is our own fault, and suing McDonald's is a cop-out. I disagree in part: a rapid increase in the obesity rate is a social problem with political solutions. However, I agree that lawsuits aren't the right response. There are much more constructive, positive, participatory responses to obesity. For example, a community can work to make its streets safe and walkable, to identify and publicize existing assets, and to provide new food and exercise options.

In the areas around Hyattsville, MD, there are no full basketball courts. This is a political issue (the authorities don't want young Black men hanging around, so they don't build courts); and it may affect adolescents' body weight. It shows the limits of conservative arguments. You can't exercise if there are no sidewalks, no basketball courts, and no grassy spaces. If the only place that lets you hang out at 10 pm is McDonalds, then you're going to eat a lot of fries. Still, that doesn't mean that lawyers will ever solve the problem by suing McDonalds on behalf of the American people. Communities have the power to take their fate into their own hands.

This is a rambling post, badly in need of reorganization; but let me add a quick summary. There are not just two ways of thinking about obesity: either individuals are responsible for what they eat, or huge corporations are responsible (and deserve to be sued). Instead, we can take responsibility as communities. This third choice is more productive and realistic than either of the others.

permanent link | comments (2) | category: a high school civics class

March 8, 2004

exhaustion

I just spent a whole day with 45 high school students, eight college students, and eight colleagues, talking intensively about the causes of obesity in Prince George's County, MD, and planning a map-making project that will take us all spring. I have overall responsibility for the project, and this first day felt like a constant crisis, starting at 7 am. The tables we ordered didn't seem to be there; we didn't have recorders for some of the focus groups; we thought we'd lost a kid; the pizzas didn't show up; sleet began to fall while the kids were outside learning how to use Global Positioning devices; and on and on. Actually, all the problems were solved and no damage was done. Once we go over the audiotape, videotape, written notes, and the maps that the kids made, I think we'll find that it was a rich and highly informative day--a window into the lives of these young people. (Or perhaps a better metaphor would be a mirror, to show the kids what they are like as a group.) But for today, I'm too tired to think straight.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: a high school civics class

February 11, 2004

a windshield tour

Today, I rode with two colleagues up and down the streets of Hyattsville, Mount Rainier, and Riverdale, Maryland--communities northeast of the District of Columbia. We are planning a high school course for later this spring, in which students will make maps to show features of the local geography that might contribute to healthy or unhealthy living. This is a fairly complex and ambitious project, now involving six graduate students or colleagues from the university, one high school teacher, and a colleague from the Orton Foundation in Vermont. Today we were simply trying to decide what precise areas we should map. The landscape is largely suburban, with strip malls, big highways, and used car lots. There are also patches of older housing on urban grids, and some large apartment complexes. Although the topography is suburban (and sprawl is an issue), the population is stereotypically urban: most people are African American or Latino, with a low-to-moderate income level, and there is a sprinkling of mostly White graduate students and artists. Although I suspect that even most residents would not describe the setting as attractive, there is great cultural diversity. Planning to make maps of an area forces you to recognize the complexity and the wealth of human assets that it contains.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: a high school civics class

November 3, 2003

community mapping

I spent this morning walking around Hyattsville, MD, with high school kids, who were entering data about each street segment into Palm Pilots. We want to collect information that will help us see what features of each block make it attractive or unattractive for walking. For example, are the sidewalks clear and continuous? How much vegetation is there? Are there curb cuts? Is there an incline? We will later collect information about (a) people's eating and exercise habits; and (b) the availability of various types of food and recreation in the neighborhood. When we put everything together, we should be able to build a statistical model showing what features of the local environment influence people's choices to walk and buy food. We'll also be able to generate public maps showing where one can walk most safely and buy the healthiest food in the community.permanent link | comments (0) | category: a high school civics class

October 7, 2003

civic education day

Today was a day for thinking about civic education from several different angles. I participated in a Steering Committee meeting of the National Alliance for Civic Education; reviewed research grant proposals submitted to CIRCLE (on aspects of youth civic engagement); and worked on my own application to the National Endowment for the Humanities. This proposal is due next week, so I'm focusing a lot of my on budgetary and other practical details. (My colleagues and I are applying to replicate our high school students' unusual oral history project in several sites, including Jackson, Mississippi and Miami, Florida. The proposed topic is segregation and desegregation in local school districts, during the period 1954-2004. Students will interview surviving witnesses, think of several alternative strategies that could have been adopted in 1954, and create interactive websites to help community members think about what should have been done. That's not an easy question, since each strategy would involve different risks and tradeoffs.)

Coincidentally, I was recently asked to write an article on the following topic: "Civic involvement and democracy in the scholarly communication commons." I proposed this tentative abstract, inspired by the history work:

There are many projects underway that help non-scholars to create sophisticated intellectual products for free dissemination on the Web. Some of these projects enlist disadvantaged adolescents, a group that's particularly distant from traditional, professional researchers. So far, there are neither aggregate poll data nor experimental results that would help us to measure the effects of such projects on the participants or their target audiences. However, those of us who are working in this area hope for several benefits. Participants should gain civic skills and values as a result of creating public goods. They should also gain academic and technical skills and interest in attending college. They should develop an understanding of the digital commons and thereby enlarge the political constituency for policies that protect the commons. Meanwhile, communities should gain from the materials generated by diverse new groups; and powerful research universities should benefit from new opportunities to collaborate with students in their vicinity. As a result, it should be possible to persuade universities to use some of their research resources for projects that would increase youth civic engagement.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: a high school civics class

September 17, 2003

mapping with kids

We've made it past the first stage of a grant competition to provide funds for our local mapping work with high school kids. That's great news, except that now I have to write a full proposal on short notice. Among other questions, I need to answer this: "What is unusual about your project?" We intend to help high school students who are not college-bound to play leading roles in original scholarly research on a matter of public importance, and see whether that work increases both their academic skills and their civic commitment. The topic, which I've discussed here before, is healthy nutrition and exercise and the degree to which these outcomes are affected by the physical environment.

The Orton Foundation provides a great collection of youth-generated maps at communitymap.org.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: a high school civics class

September 10, 2003

youth and the history of desegregation

School desegregation is a public issue that involves and affects youth. It’s a vital contemporary matter that requires historical background to understand. It continues to provoke debates among reasonable and well-intentioned people, who disagree about both goals and solutions. In all these respects, it is an ideal topic for sustained work in schools as a key component of civic education.Last fall, we worked with students at a local high school in Maryland to create an interactive, deliberative website about the epic history of desegregation in their own district. ("We" means the Democracy Collaborative and the Institute for Philosophy & Public Policy, both at the University of Maryland.) We have now collaborated with NABRE, the Network of Alliances Bridging Race and Ethnicity (pronounced “neighbor”), to develop a plan for a replicating the same project in many school districts. This year is the 50th anniversary of Brown v Board of Education, the first of a series of 50th anniversaries of events in the Civil Rights Era. Coming to understand the difficult choices made in one's own community seems both a good way to commemorate this history and an excellent foundation for making choices today.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: a high school civics class

August 18, 2003

Miles Horton on improvisation

I came across a quote today by Myles Horton, the great founder of the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee, which trained Rosa Parks and so many other heroes of the labor and civil rights movements. Horton said that he had learned from decades of nonviolent struggle against injustice that "the way to do something was to start doing it and learn from it."

I recognize the limitations to this approach. It's good to have a "strategic plan" with goals and methods all arranged in proper order. Yet often in civic work, improvisation is both a necessity and an inspiration. As long as you keep your mind open, listen to others, and try to learn from everything you do, it's sometimes wise to start working even before you know exactly what you are doing.

I write this as I continue to read articles about local geography and its effects on nutrition—all because I want to obtain a grant that can support our local work with kids. I don't know where that work will take us, but it seems important to sustain a nascent institution by grasping the opportunities that come along. (I don't mean to compare myself and my colleagues to Miles Horton, because we're not struggling against injustice as he did. But we do have a similarly cavalier attitude toward planning.)