April 14, 2011

John Gaventa on invited and claimed participation

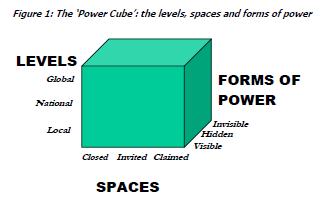

Today, I will be interviewing John Gaventa at a Tisch College forum to which all are welcome. Gaventa has been a major figure in democracy and popular education since his student days in the early 1970s. One of his recent contributions is the PowerCube, a simple device that activists can use for analysis and planning:

I am especially interested in the dimension that runs from "closed" to "invited" to "claimed." Much of my work has involved trying to get powerful institutions to "invite" public participation by, for example, reforming elections to make them more fair, enhancing civic education, advocating changes in journalism, or recruiting citizens to deliberate about public policy. Increasingly, I believe that democratic processes must be claimed, not invited, if they are to be valid and sustainable.

For instance, in 2009, angry opponents of health care reform deliberately disrupted open "town meetings" convened by Democratic Members of Congress. The Stanford political scientist James Fishkin published an argument for randomly selecting citizens to discuss health care instead of holding such open forums. That was a classic proposal for "invited" democracy. The New York Times chose to give his essay the headline, "Town Halls by Invitation." I would now say that democratic participation cannot be by invitation--it must be a right claimed or created by ordinary people, whether elites like it or not.

On the other hand, when officials do invite participation, that is often in response to public pressure or demand. In such cases, formally "invited" spaces are actually claimed ones. One of the most important innovations is Participatory Budgeting (PB). As I understand it, the Labor government of Porto Allegre, Brazil, invented PB to reduce political pressure on itself as it faced hard budget choices. But PB became so popular that it survived changes of party control in Porto Allegre and spread to many other municipalities around the world. In such cases, reform begins with an invitation but becomes an expectation.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: deliberation , democratic reform overseas

April 1, 2011

participatory budgeting in Recife, Brazil wins the Reinhard Mohn Prize

The best civic engagement process in the world is participatory budgeting in Recife, according to 11,600 German citizens who voted for their favorite among a set of impressive nominees. In "participatory budgeting," large groups of citizens deliberate and vote to allocate municipal capital budgets. Many evaluations have found juster decisions, much lower corruption, and higher levels of democratic legitimacy as outcomes.

I consulted on the Reinhard Mohn competition and also nominated Hampton, VA for the prize. Hampton came in fourth (in the world) with 1,935 votes. I liked Hampton because the city has systematically embedded deliberation and public participation in most of its systems--education, policing, budgeting, parks and recreation, and planning--for decades. Hampton now also uses participatory budgeting.

On the other hand, I understand what the German voters were thinking. Brazil is the birthplace of participatory budgeting, which is one of the most impressive democratic innovations of the last quarter century. Recife seems to be the best example--notable (among other things) for having a separate youth participatory budget. As one astute voter wrote, "In this project I was particularly impressed by the children’s citizen budget. This makes it possible for people to experience and learn about the basic principles of democracy from a very young age. Anyone growing up with that experience will naturally engage in democratic processes as an adult."

permanent link | comments (0) | category: democratic reform overseas

February 1, 2011

Egypt as a velvet revolution

In a New York Review article in 2009, Timothy Garton Ash offered some generalizations about the "Velvet Revolution" [VR] as a historical phenomenon. Its archetype is Eastern Europe in 1989, but other important examples have occurred in South Africa, the Philippines, Chile, and now perhaps in Egypt. After the metaphor of velvet seemed to wear out, the language shifted to colors, so that we have now seen a Rose Revolution in Georgia, an Orange Revolution in Ukraine, a Pink Revolution in Kyrgyzstan, a frustrated Green Revolution in Iran, and a Jasmine Revolution in Tunisia. I haven't seen much mention of a color in Egypt, but citizens there are clearly following the Velvet Revolution or Color Revolution script.

Ash writes:

Painting with a deliberately broad brush, an ideal type of 1989-style revolution, VR, might be contrasted with an ideal type of 1789-style revolution, as further developed in the Russian Revolution of 1917 and Mao’s Chinese revolution. The 1789 ideal type is violent, utopian, professedly class-based, and characterized by a progressive radicalization, culminating in terror. A revolution is not a dinner party, Mao Zedong famously observed, and he went on:

A revolution is an uprising, an act of violence whereby one class overthrows another…. To right a wrong it is necessary to exceed proper limits, and the wrong cannot be righted without the proper limits being exceeded.

The 1989 ideal type, by contrast, is nonviolent, anti-utopian, based not on a single class but on broad social coalitions, and characterized by the application of mass social pressure—"people power"—to bring the current powerholders to negotiate. It culminates not in terror but in compromise. If the totem of 1789-type revolution is the guillotine, that of 1989 is the round table.

Two other defining features of the Velvet or Color Revolution:

1) It locates the ideal outcome not in a hitherto unrealized future, but in a real past or in an actual existing situation from today's world. I cannot speak for Egyptians, but I suspect they want a society more like today's Turkey, Spain, or Sweden. In Velvet Revolutions, the actual parliamentary democracies of the present are treated as normal, and the goal is to attain normality. This is very different from trying to end history or achieve a novel kind of state.

2) It is self-limiting, concerned to avoid replacing the old tyrant with a new tyrant. Mass movements can easily be taken over by well-placed, professional revolutionaries who then become dictators. Mass nonviolent protests can easily turn violent, and once political killing becomes common, it is extremely hard to avoid civil war and then repression. Successful mass movements limit themselves by finding some bright-line rule, a restriction on their own power, that they demand their own members follow. Non-violence is one such rule, and it has the advantage of being clearly defined. But it is not the only workable rule. In Iran in 2009, protesters seemed to fasten on the rule: "Hurt the machines, love the human beings." They would violently pelt Revolutionary Guard motorcyclists with stones until the Guardsmen were unseated, at which point they would give them medical assistance. In Egypt, one emergent rule is: "Molotov Cocktails yes, Guns no."

permanent link | comments (0) | category: democratic reform overseas

December 3, 2010

youth civic engagement and economic development in the Global South

I will be talking later today about this topic. Since I am far from an expert on the subject, I intend to facilitate a conversation rather than lecture. I will put some points on the table for discussion:

1. According to the World Bank (2007), "Today, 1.5 billion people are ages 12–24 worldwide, 1.3 billion of them in developing countries, the most ever in history." Incorporating that enormous population into political and civic life represents a challenge and an opportunity. ("Civic and political life" means voting, activism, service, belonging to groups, deliberation, careers in the public and nonprofit sectors, production of media and culture--and I would not exclude revolution or war under extreme circumstances.)

2. Among those 1.3 billion young people are many millions who have been involved in criminal gangs or conscripted as child soldiers. The challenges and opportunities are particularly dramatic in those cases.

3. In countries where the age distribution is skewed toward the young, investing adequately in children and teenagers is very difficult. The older generations lack sufficient cash, and even time, to provide for youth when the youth/adult ratio is too high. This is a vast and probably insoluble problem, but it's important to look for high-impact strategies.

4. From evaluations of youth development programs, we know that when "at risk" young people are given opportunities to deliberate, serve, and act politically, they learn, develop healthy personal behaviors, and integrate successfully into society. A moving example from the United States: On entering YouthBuild, the participants--young American adults without high school diplomas--estimate their own life expectancies at 40, on average. Upon completing the program, they have raised the average estimate to 72: evidence that they have gained a sense of opportunity, optimism, and purpose by working together, building houses and studying and discussing social issues.

5. Older people make political decisions that are far from optimal for youth. They pour public money into retirement benefits and health care at the end of life while under-investing in education and preventive health care. Also, entrenched elites (who are, by definition, older) tend to make corrupt decisions. Many countries are experimenting with "social accountability" as a tool for more equitable and less corrupt policy. That means giving the power to make decisions to citizens, organized in deliberative forums. In some places, youth are specifically included in social accountability. For instance, in Fortaleza, Brazil, 50 young people helped shape the municipal budget (PDF, p. 53). Hampton, VA has created a whole pyramid of engagement for its young people, capped by empowered youth councils. Although I don't think we yet have evidence that youth participation produces dramatically better social outcomes, that is highly plausible given (1) the persuasive evidence for social accountability, plus (2) examples in which young people have participated effectively in public processes.

6. Other policies that affect youth civic engagement, for better or worse, include: the extent and content of primary and secondary education; conscription and national service (which sometimes includes civilian alternatives); the criminal justice system and how it treats juvenile offenders; and the rules of the electoral system (including when the voting age is set). These policies can be deeply harmful: for example, when young Americans are permanently stripped of the right to vote because of felony convictions. Or they can be helpful--as when universal schooling supports civic learning.

7. There is nothing intrinsically good about youth civic engagement. Fascism was basically a youth movement. But some societies create a healthy dynamic in which young people introduce new energies, interests, and ideas, while older people maintain institutions and transmit values and experience. Other societies discourage constructive engagement, and the consequences are almost always harmful.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: advocating civic education , democratic reform overseas

October 15, 2010

welcome to Participedia

My friend Archon Fung and others have built "Participedia," an online archive of articles about public participation and democratic innovation around the world. It's wiki-style, so anyone can add cases and edit the ones that are there already. The site says:

- Participedia collects narratives and data about any kind of process or organization that has democratic potentials. A process is democratic when it functions to include, empower, or give voice to those affected by collective decisions in making those decisions. That is, the Participedia understanding of "democracy" is broad, and does not prejudge where these processes might be found, how they might be organized, or who might create them.

The site already contains main important examples. They are looking for failures, too, which is very important because we tend to collect examples of success even if the odds of replication are poor. Smart strategic planning requires learning from mistakes.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: democratic reform overseas

August 12, 2010

what is the best participatory process in the world?

The Bertelsmann Foundation--the largest foundation in Europe, I believe--will give its Reinhard Mohn Prize in 2011 to the best project anywhere in the world that "vitalizes democracy through participation." I am serving on an advisory board for the prize, but a major aspect of the competition this year is open and public. You can go to this website and nominate a project or read and vote on the nominees (or both).

I personally nominated the Unified New Orleans Plan, which was written after Hurricane Katrina by thousands of citizens whom AmericaSpeaks convened for town meetings; Community Conversations in Bridgeport, CT; and deliberative governance in Hampton, Va. These are strongly institutionalized, politically significant examples of public deliberation in the US. They have recruited diverse and representative citizens in large numbers, addressed real problems, and strengthened their communities' civic cultures.

There are 78 other nominees right now. They include clever ideas, like an online space for citizens of different EU countries to agree to vote together. Promising work comes from unexpected places, like a deliberative polling exercise at the municipal level in China. There are many e-democracy platforms, most of which seem to be suites of online tools for following the government and discussing issues. The Danish Board of Technology, which has an impressive track record of public engagement over many years, convened people in 38 nations to discuss global warming together--an impressive experiment that yielded news reports in many of the countries.

Participatory Budgeting (which gives citizens the right to allocate public funds in deliberative meetings) has spread from its homeland of Brazil to places like Tower Hamlets, London and the Indian state of Kerala. Some important legislative reforms have been nominated and should be celebrated, although I am not sure they meet the criteria of the prize. The Central Information Commission in India is an example.

I am not sure that my own nominees are the best, but I am most enthusiastic about all the examples that are multidimensional, lasting efforts, driven by several institutions instead of only the government, and involving work, cultural production, and education as well as dialogue and advice. Some examples other than my own nominees would include Co-Governance in Belo Horizonte, Brazil, perhaps the Abuja Town Hall Meetings in Nigeria (if they are genuine democratic spaces), and Toronto Community Housing’s Tenant Participation System.

Vote for your favorites!

permanent link | comments (0) | category: deliberation , democratic reform overseas

June 22, 2010

the European Charter of Rights on Active Citizenship

The "Charter" is an effort "to develop the concept of 'Civic Participation', which is mentioned in the European Constitution (art. 47 and art. 72, second part), but then not explained."

It is a draft for public debate. It aims to address "the paradox" that, "while citizens and their autonomous organizations are usually asked to contribute with material and immaterial resources to filling the 'democratic deficit' of the European Union, they are, at the same time, hardly considered and often mistrusted by public institutions."

The "right to participation" is thus defined: "Each individual has the right to actively participate, through Autonomous Citizens’ Organizations (ACOs), in public life." This may sound alarmingly collectivist--can't individual Europeans participate directly in public life?--but I think the goal is to supplement the extensive individual civil and political rights that are already enshrined in European law with a formal acknowledgment of associations.

ACO's are assigned rights in this charter, but most of them sound like rights already protected under laws concerning citizens' free speech and assembly. For instance, the charter says, "Whenever citizens’ rights and general interests are at stake, ACOs have the right to intervene with opinions and actions." European citizens already have rights to state their opinions, and they are within their existing rights if they choose to express themselves through associations. Thus the most interesting parts of the charter are the obligations imposed on governments to engage ACOs, plus the appendix that lists "best practices" for doing so.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: democratic reform overseas

April 7, 2010

participatory budgeting in Chicago

Participatory budgeting started in Brazil, when residents of poor urban neighborhoods were given control over capital budgets. They now meet in large groups and decide how to spend government funds deliberatively. The outcomes of participatory budgeting in Brazil include better priorities, greater public trust in government, and much less corruption. The last benefit might seem surprising, but it appears that when people allocate public money, they will not tolerate its being wasted.

Participatory budgeting is one of many important innovations in governance that have originated overseas and that should be imported to the US. Now is a time of great creativity in democratic governance, with the US generally lagging behind. We suffer from too limited a sense of the options and possibilities.

I believe there has been some participatory budgeting in California cities. And now Chicago Alderman Joe Moore announces:

As a Chicago alderman, I have embarked on an innovative alternative to the old style of decision-making. In an experiment in democracy, transparent governance and economic reform, I'm letting the residents of the 49th Ward in the Rogers Park and Edgewater communities decide how to spend my entire discretionary capital budget of more than $1.3 million.

Known as "participatory budgeting," this form of democracy is being used worldwide, from Brazil to the United Kingdom and Canada. It lets the community decide how to spend part of a government budget, through a series of meetings and ultimately a final, binding vote.

Though I'm the first elected official in the U.S. to implement participatory budgeting, it's not a whole lot different than the old New England town meetings in which residents would gather to vote directly on the spending decisions of their town.

Residents in my ward have met for the past year — developing a rule book for the process, gathering project ideas from their neighbors and researching and budgeting project ideas. These range from public art to street resurfacing and police cameras to bike paths. The residents then pitched their proposals to their neighbors at a series of neighborhood "assemblies" held throughout the ward.

The process will culminate in an election on April 10, in which all 49th Ward residents 16 and older, regardless of citizenship or voter registration status, are invited to gather at a local high school to vote for up to eight projects, one vote per project. This process is binding. The projects that win the most votes will be funded up to $1.3 million.

I am strongly opposed to discretionary budgets for legislators. That's just a way for them to buy reelection with public funds. But the fact that Alderman Moore has such a budget is not his fault, and he is using it for an excellent experiment.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: deliberation , democratic reform overseas

August 20, 2009

village democracy in India

One of the most remarkable innovations in democracy comes from India, where the Constitution requires every village (but not urban areas) to have both elected councils and empowered open meetings called "gram sabhas" (GS's). Vijayendra Rao of the World Bank and Paromita Sanyal of Wesleyan write, “The GS has become, arguably, the largest deliberative institution in human history, at the heart of two million little village democracies which affect the lives 700 million rural Indians.” PDF

Apart from the scale of this experiment, its most remarkable features are (1) the right to active participation that is enshrined in the Indian Constitution, and (2) the steps required to promote equality of gender and caste.

As the government itself explains, Article 40 of the original Indian Constitution required "that the State shall take steps to organise village panchayats [councils] and endow them with such powers and authority as may be necessary to enable them to function as units of self-government." But there were problems with the representativeness, fairness, and power of the panchayat system. As a result, in 1992, the Indian "Constitution was amended to … provide for, among other things:

- direct elections to all seats in Panchayats at the village and intermediate level, if any, and to the offices of Chairpersons of Panchayats at such levels;

- reservation of seats for the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes in proportion to their population for membership of Panchayats and office of Chairpersons in Panchayats at each level;

- reservation of not less than one-third of the seats for women;

- devolution by the State Legislature of powers and responsibilities upon the Panchayats with respect to the preparation of plans for economic developments and social justice and for the implementation of development schemes;

- [funding for the Panchayats from] grants-in-aid [and from] designated taxes, duties, tolls and fees;

- barring interference by courts in electoral matters relating to Panchayats.

There must be a gram sabha in each village at least once per year, although I think that is a statutory provision and not contained in the Constitution itself. "A Gram Sabha may exercise such powers and perform such functions at the village level as the Legislature of a State may, by law, provide." Apparently, some make substantial decisions about spending and planning.

The most remarkable impact of this reform has been to strengthen the confidence, standing, and voice of the poor, of women, and of low-caste individuals. Rao and Sanyal conclude that the “GS facilitate the acquisition of crucial cultural capabilities such as discursive skills and civic agency by poor and disadvantaged groups. ... The poor and socially marginalized deploy these discursive skills in a resource-scarce and socially stratified environment in making material and non-material demands in their search for dignity.”

permanent link | comments (0) | category: democratic reform overseas

August 3, 2009

the view from South Africa

(Washington, DC) Xolela Mangu, a distinguished South African social scientist and columnist, joined our conference last week on the Obama civic agenda. In his national column, he reflects on "service" (with its hints of moral obligation, on one side, and dependency on the other) versus civic empowerment:

LAST week I participated in a cross-Atlantic conference with officials and academics closely aligned with the Obama administration.

On this side, I was joined by the distinguished scholar-activist, Harry Boyte.

The conference was convened to ask one question: how far has Obama gone in fulfilling his campaign promise of making active citizenship the centre of his administration?

The chairman of the Corporation for National and Community Service, Alan Solomont, provided a wide-ranging account of what the administration had done in increasing funding for public service and getting the youth actively involved in community service work.

The administration has also done well in opening up the government.

Obama’s foreign policy speeches have also set the tone for civic engagement around the world.

However, Harvard University’s Marshall Ganz was more cautious about the emphasis on service as opposed to building community.

Boyte could sense technocracy creeping into the language of the administration, from the mobilising theme of “yes, we can”, with the government and the people working together, to “yes, we should”, which is more about doing for communities.

My own view is that instead of foreign policy discussions proceeding only in terms of the human rights/national interest dichotomy, we should be exploring international collaboration around issues such as active citizenship.

Interestingly, the masthead editorial in the same edition of the same newspaper (The Weekender) echoes the same themes. Commenting on recent grassroots protests in South Africa, The Weekender says:

The community-based protests have been the catalyst for a long-overdue conversation on the "service delivery" issue, which was all but drowned out of the election campaign earlier this year by the power struggle within the ANC and Zuma’s battle to avoid prosecution. But it is not clear the party has any viable alternative to vague promises based on a top-down delivery model--hence the hastily arranged national summit to establish the cause of the flare-ups. ...

There is a lot more to it than unrealistic expectations, though. The very basis of the term "service delivery" needs to be revisited--what is meant by it, how is it understood by the poor, and is it appropriate given the capacity and skills challenges the state faces?

"Service delivery" implies from the outset that poor communities are passive recipients of state largesse, and this clearly accords with the view of many ruling party politicians, who unashamedly link political support with handouts. Yet it has been shown the world over that community involvement in projects such as infrastructure development not only helps ensure that the product is looked after but enhances individual confidence, self- respect and skills levels.

Several commentators have pointed out that the nub of the protests is not so much about delivery--although that clearly leaves much to be desired in most parts of the country--but the fact that communities are seldom consulted about what they really want.

"Community service" is not the same thing as "service delivery." The former usually involves amateurs who are unpaid or given small stipends; the latter, agencies and professionals. Yet it is no coincidence that the two phrases share a word. Their shared problem is a conception of people as needy clients, not as active agents. In both the United States and South Africa, now that left-of-center governments hold power, there is a quiet struggle underway between "service" and civic agency.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: Barack Obama , democratic reform overseas

May 13, 2009

nonviolence and the Palestinian cause

For several months, I have been thinking of a post about nonviolent resistance in the Palestinian territories. I'm finally writing now because of a thoughtful and well informed article on that very subject: "The Missing Mahatma: Searching for a Gandhi or a Martin Luther King in the West Bank," by Gershom Gorenberg in the Weekly Standard.

I recommend the whole piece. It reinforces my sense that a nonviolent struggle could produce a Palestinian state on somewhat more advantageous terms than are now available. One could say that Israel is "vulnerable" to a nonviolent strategy, but equally Israel needs to escape from the nightmare of occupation. The Jewish State seems incapable of achieving a resolution by itself--which may be the nature of a master/slave dialectic--so a nonviolent victory for the Palestinian cause would also be the best thing that could happen to, and for, Israel.

Gorenberg documents what I already knew in less detail: there are, and have long been, nonviolent Palestinian resistance efforts. They are usually small-scale and always overshadowed by violence. That is hardly surprising. Nonviolence takes tremendous commitment, coordination, and discipline. Nonviolent efforts are very easily broken up, discouraged, or overshadowed by forces on either side of the conflict that prefer violence. Successful nonviolent campaigns are exceedingly rare. The Palestinian case is typical rather than strange.

For me, the core principle is not nonviolence. I'm glad we invaded Normandy in 1944, and I hope the Taliban loses on the battlefield. I'm not a pacifist, but I do think that self-limitation is crucial. Lord Acton was right; unlimited power corrupts. Revolutionary struggles (the ones that aren't crushed) typically end in tyranny or fratricide, because their leaders can't stop using the tools that have brought them to power.

We could even view liberal democracy as a device for promoting limited political movements. There are enough openings at different levels of a democracy--and enough civil rights--that political causes don't automatically fizzle out. Yet each movement is always checked by its rivals, causing it to be limited and disciplined. The Palestinians don't have a democratic context in which to organize. Their leaders and partisans must limit themselves, must set their own rules. Fatah is a case study of what happens when they don't. Within its own sphere, it is corrupt and violent. Beyond its domain, it is weak. If Fatah somehow wins, the Palestinian people will have to struggle to get a decent government out of it.

Nonviolence is an example of a self-limitation, but it is not the only one. The American revolutionaries of 1776 fought with guns, yet they showed admirable restrain that paved the way for a successful republic. In the First Intifada, the Palestinians managed to avoid guns and bombs in favor of stones for the better part of two years. The signature of the Intifada was children throwing things at tanks. As Gorenberg writes:

The uprising was unarmed, if arms refers to guns and not to gasoline-filled bottles. The leaders of the uprising were "opposed in principle" to using firearms and explosives, says Yaakov Perry, who was deputy chief of the Shin Bet, Israel's internal security service, at the start of the Intifada and became head of the agency soon after. The uprising's leaders deliberately sought to turn weakness into political strength, knowing that "in the international arena, Israel could not deal with the picture of the boy holding a rock facing a tank," Perry says. This is close to Gandhian logic, but only close, unless one imagines Gandhi urging followers both to go on strike and to master the slingshot. Unarmed did not mean nonviolent.

I think the tactics of the First Intifada could be effective today, but true nonviolence would be better. I say this not because of an ethical scruple but because of the nature of collective action. To get people to do something very hard, and all at the same time, requires a very clear definition of what they must all do. You need a bright-line test, or else individuals will start pushing the limits, and discipline will break down. "Don't ever hurt anyone physically" is a clear rule, a bright line. Using stones and Molotov cocktails but no bombs is too vague and ad hoc; it invites escalation.

Of course, a clear definition of rules is not the only condition of success. Leadership is also essential, although I think Gorenberg somewhat overestimates the individual contribution of Martin Luther King. (There were many other key leaders in that movement.) He does recognize the importance of a third factor: ideological commitment to nonviolence itself. When we face brutality and oppression, the temptation is overwhelming to strike back. ("I and the public know / What all schoolchildren learn, / Those to whom evil is done / Do evil in return.") It helps enormously if participants in a social movement believe in nonviolence (or in other serious restraints)--not just as wise precautions or clever tactics, but as deep moral imperatives. For instance, it helps if they think that God wants them to turn the other cheek.

Islam is not more violent than Christianity or Hinduism. All three religions are generally soaked in blood, and Islam has modeled tolerance and restraint as often as the others have. But it helped both Gandhi and King that there were minority traditions in their own faiths that were extreme and radical about pacifism. As King asked rhetorically from the Birmingham Jail, "Was not Jesus an extremist for love? 'Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you.'" Franciscans, Quakers, and others before King had made rigorous pacifism a tradition that he could evoke. Although there are certainly peaceful and peace-loving traditions in Islam, I'm not sure there is anything as uncompromisingly and ascetically pacificistic as we find at the margins of Christianity and Hinduism.

But Palestinians have an opportunity to create their identity out of nationalist, ethnic, religious, and cosmopolitan strands. As for their majority religion, Sunni Islam, it is dynamic and flexible, as all faiths are. Gorenberg shrewdly writes:

Religious traditions come blessed with contradiction. The Hebrew Bible declares in the Book of Isaiah that "in the days to come . . . they will beat their swords into plowshares." In the Book of Joel it proclaims, "Beat your plowshares into swords, and your pruning hooks into spears." For the individual believer, there is an "essential" Islam, Judaism, or Christianity constructed by taking one part of the tradition as obvious truth, interpreting others in its light. Seen from the outside, a religion is only a set of possibilities.

If Palestinians could develop the pacifist possibilities that are available in their various traditions, the future could be much better for them, and for the world.

permanent link | comments (1) | category: democratic reform overseas

April 3, 2009

conservatism in the Nation of Shopkeepers

The British Conservative Party wants to make the preservation of small, locally-owned business a major objective. Their Leader, David Cameron, says, "Small shops are the lifeblood of local economies and provide a lifeline to local residents - and their survival is vital. ... If we care about our communities, and the local, independent retailers that give them their character, then it's our responsibility to support them." A Conservative Party report has argued that small shops "reflect something of what is best about modern Britain itself. They are independent and entrepreneurial, they display a rich cultural and ethnic diversity, and their eclectic differences add real character to our towns, cities, and villages." But these small businesses are closing fast, in part because of big chains.

The Tories are conjuring up images that I recognize with some nostalgia, having grown up substantially in Britain. "High Street" businesses over there include ancient pubs, independent butchers with sawdust on the floor, kabob stands, hobby stores selling stamps and model airplanes, corner groceries owned by South Asians, cafes with bottles of "brown sauce" on the formica tables, dusty antiquarian book shops, and newsstands lined with specialist magazines. As the Conservatives say, these business support an everyday culture that has British roots but that is deeply diverse today, both ethnically and regionally. It wouldn't be British if there weren't Asian, West Indian, and Irish owners and workers among the white, Anglo-Saxon ones.

I think the Tories' new emphasis is a politically smart move, because there is much affection for local businesses and the local cultures they support, and this affection crosses national and party lines. (Crunchy liberals are also enthusiastic about small, locally-owned businesses.) I guess you could criticize the Tories' position on at least two grounds: 1) They won't actually be able to save small businesses, so it's just rhetoric, and 2) they are promoting a kind of communitarianism that is nostalgic and soft and not sufficiently concerned with power. Then again, maybe they will figure out policies to revive and preserve local business, and maybe local business are a real source of power, a counterweight to transnational markets. In any case, this move seems like a genuine form of conservatism, much more authentic than the weird mixtures of libertarianism and authoritarianism that are common on the American right today.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: democratic reform overseas

February 17, 2009

thoughts on Hugo Chavez

After President Chavez of Venezuela won the right to seek perpetual reelection, it occurred to me that:

1. Venezuela poses no risk to the United States. Its government must sell oil on the international market or it will collapse economically. If Chavez decides not to sell to us, we can still buy oil at the global price: it's a commodity. Leaving aside short-term psychological shocks from a Venezuelan embargo, they have little power to affect world prices. They can use their oil revenues to fund overseas military adventures, but their military options are limited. Because Venezuela does not threaten us, we have limited standing to try to influence that country. However ...

2. Chavez is almost certainly moving in exactly the opposite direction from what we need in the 21st century. He is centralizing power in the national government; merging military, administrative, and partisan-political authority; combining personal macho charisma with media celebrity and formal power; reducing political pluralism, checks-and-balances, and civil liberties; exploiting fossil fuels to the maximum; monopolizing the market, press, and state sectors; and trying to exacerbate the deep tensions in Venezuelan society instead of helping everyone to work together. I'd recommend a 180-degree different course. But ...

3. Chavez occupies a huge and growing political niche. It is remarkable, in a world where about one billion people live on less than $1 per day, one quarter of children in developing countries are underweight because of inadequate food, and one quarter of children in the same countries are not in school, that there isn't a more active and aggressive political movement that demands urgent economic redistribution.

I would generally favor moderate and market-based solutions to poverty, but the credibility of the market must surely suffer now that Wall Street and the City of London have been shown to be incapable of managing even their own affairs. I think there would already be a much more robust global radical left if we hadn't just passed through the long aftermath of the Soviet fiasco. Russian Communists first eliminated many rivals on the left and then collapsed, leaving a remarkable void. If Intel and Microsoft suddenly went bankrupt, there would be a lot fewer new computers in production next year. But the computer industry would revive to meet the demand, and the same thing will happen with the redistributionist left.

Thus for me the interesting question is to what extent Chavez (and Evo Morales, and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad) will fill the political niche of opposition to global capitalism. From my own biased perspective, it seems much better if someone like President "Lula" da Silva of Brazil can obtain international leadership. In fact, I'd love to see the Obama administration take thoughtful and effective steps to build Lula up--not in our interests so much as the interests of the Global South.

permanent link | comments (3) | category: democratic reform overseas

December 23, 2008

civic innovation in Britain

I've written before about the civic agenda of the current British government, which includes better civic education in schools, decentralization of power, and innovative opportunities for citizens' work. Via Henry Tam, here is a government paper entitled "Communities in Control: Real People, Real Power." It's a long and detailed paper, but here are some highlights:

- Participatory budgeting is a Brazilian invention; citizens are invited to meetings where they can collectively allocate portions of the local capital budget to purposes of their choice. In Brazil, participatory budgeting has increased the fairness of public-sector spending and has reduced corruption. It is now being used in 22 local councils in Britain, and the UK Government wants it to be used everywhere. (I believe that the Obama Administration should build Participatory Budgeting into its economic recovery plan.)

- Citizens Juries are randomly selected bodies of citizens who meet for a substantial amount of time, deliberate, and make public decisions. Citizens Juries are now being used in the UK. A recent comment on this blog suggested that they are a strategy to avoid the traditional forms of representation, such as students unions, which are less tractable. That's possible, but there have been very impressive experiments with Citizens Juries in other countries.

- The Government intends to implement a "duty to involve" rule that would apply to most local service-providers. That reminds me a bit of the "maximum feasible participation" mandate of the War on Poverty in the US during the 1960s. Maximum feasible participation was hardly a clear-cut success, but one interpretation is that we did not yet have a sufficient infrastructure (set of practices, institutions, and trained people) to handle it. The infrastructure has improved over the last 40 years--probably in the UK as well as here.

- The paper acknowledges the importance of "strong independent media" and promises support for "a range of media outlets and support innovation in community and social media." It's tricky for a government to intervene in the news media. One must consider freedom of the press and expression. On the other hand, the 20th-century local media system is collapsing, and governments should find ideologically and politically neutral ways to promote healthy local news and debate.

- One of the major themes is civic renewal through decentralization. Gordon Brown has argued that the 20th-century Labour Party erred by trying to implement democratic socialism in a state-centered, nationalist form. In the developing world, centralization promoted various forms of corruption, whereas decentralization has lately permitted citizens to play more constructive roles.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: democratic reform overseas

December 17, 2008

the European city as site of citizenship

I met yesterday with a German visitor, a former mayor as well as an activist shaped by the sixties and by direct exposure to the Frankfurt School. We talked about European self-governing cities as sites of citizenship.

There is a very old tradition of autonomous or quasi-autonomous European cities, governed by guilds and associations (corporations; comuni; freie Städte). It was in the medieval Italian city-states that civic republicanism was reborn, in imitation of classical ideals of eloquent deliberation, military and civilian service, and mutual obligation. Autonomous European cities also built an impressive array of institutions: hospitals, churches, alms houses, schools, colleges, and green spaces. By the seventeenth century in the Atlantic countries, and by 1900 in Central Europe, all these cities had become subject to large nation-states, managed from their metropolitan capitals. But even in Britain, where power and population shifted early to London, the provincial cities continued to construct impressive nonprofit and public institutions that reflected and developed their local cultures and continued local traditions of governance. Lord Mayors in British cities still wear medieval or renaissance garb, for a reason.

The twentieth century, as Gordon Brown has noted , was an era of centralization. Social democrats, conservative nationalists, and even Thatcherite neoliberals all generally disparaged or ignored the traditions of civic autonomy. But those traditions could be revived--and may be reviving--as the European Union draws power away from the nation state. Brown, a Glaswegian, has explicitly evoked the civic traditions of his city in Victorian times, before his own party helped to centralize authority in London.

Ambrogio Lorenzetti, "The Effects of Good Government on the Life of the City," in the Palazzo Publico (seat of the comune), Siena

Shouldn't we worry that citizenship defined by a town or city is exclusive? What about immigrants and other newcomers? That is a concern, but it's worth noting that some of the old self-governing cities (from Venice to London) were highly cosmopolitan, and cosmopolitanism was basic to their identity. I recognize that London apprentices used to riot against Flemish and Huguenot migrants; and Venice coined the very word "Ghetto" as the place to lock its Jews. But there were also traditions of inclusion. I may be over-influenced by personal experience, but I happened to attend a primary school within the medieval limits of the City of London, where the Christian socialist headmaster taught his rather diverse student body to see themselves as citizens of the ancient corporation. A recent Lord Mayor of that same corporation had exactly my (Jewish) name, Peter Levine. As a child, I was proud of my American identity but could simultaneously consider myself a Londoner, because London has always been a melting pot.

But wasn't civic government highly stratified and unequal, with local ruling classes lording it over local proletariats? Again, that's a real concern; but I would offer two responses. First, cities should not be completely autonomous. They should be taxed, regulated, and funded by higher levels of government whose principles include fairness and equality. Second, although I favor equality, I also believe that the owners of capital need discretion and will always have a privileged position. So our goal should not be to remove inequality but to tie the interests of the wealthy to those of the community. The wealthy class in a proud and quasi-autonomous city is more embedded and accountable than the wealthy class in a large nation state or an international market.

Finally, as Steve Elkin argues, municipal politics is an excellent school of democratic citizenship. The scale is big enough, and the institutions are formal enough, that every kind of issue arises--from economic redistribution to morals to global warming. But the scale is modest enough that problems are concrete and citizens have opportunities for personal leadership and face-to-face interaction.

Overall, this is an argument for what the Europeans call subsidiarity (pushing authority down to the lowest practicable level) as way to address the "democracy deficit" and restore a sense of active citizenship.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: democratic reform overseas

November 5, 2007

social accountability in the USA

In Paris last week, I met a senior minister from Uganda who said that not many years ago, 83 percent of Uganda's education budget was wasted or stolen--not spent on education. I also met a Filipino activist who said that in his country, textbooks were often stolen or lost before they reached classrooms. Both countries have achieved enormous improvements by involving citizens in monitoring and assessing school budgets and administration. According to independent evaluations, 80 percent of education funds now reach schools in Uganda, partly because the money is tracked by citizens.

It occurred to me that in the District of Columbia, about 71 percent of the education budget is not spent on schools. Some of it may be properly used for such purposes as special education. But most of the 71 percent is lost in the downtown bureaucracy. The Washington Post has printed photos of stacks of textbooks that were never distributed to schools; electronic equipment is routinely delivered without software or support. These statistics and stories are very reminiscent of Uganda and the Philippines, and indeed of most of the world.

The obvious question is whether we could use public participation in the US as a tool to reduce serious corruption and waste. This would be a great achievement because ...

1. One of the worst sources of disadvantage in our society is the dramatically unequal quality of education. An obvious way to improve education for Washington's least advantaged students would be to seize some of the $7,200 per student that is currently being used/wasted in the downtown bureaucracy so that it could be spent instead on smaller classes and better facilities.

2. Getting the public involved in accountability might shift the attention away from test scores and toward administration. Today's high-stakes tests are supposed to motivate teachers and students to work harder and more effectively--that is the main strategy for improving education. When students fail the tests, we start to wonder whether public schools can possibly achieve success (or whether our kids can possibly succeed). If citizens could audit or review the performance of their schools, they might shift the pressure away from teachers and students, who, after all, receive less than 30 percent of the budget in DC. Citizens might conclude that the marginal impact of reforming central school systems would be much greater.

3. Public participation would be an alternative to the main accountability measures that are currently used or contemplated in our schools today. We test kids and punish them for failing; and we allow parents to take their kids out of schools. In Washington, roughly half of the student body has already left, either for the suburbs or for charter schools; but we don't see better performance in the public system--nor are the charters very successful. Maybe it would work better to get citizens directly involved in school reform.

4. Students could help to monitor their own schools, which would be a powerful form of civic education.

5. I believe that the Achilles heel of the American left is the poor performance of public institutions, such as the DC Public Schools. At some level, all of us--including left-liberals--know that such systems are deeply flawed. We lose political struggles, not because Americans love corporations, nor because voters are blind to social needs, but because they don't believe that public institutions are effective and trustworthy tools. It would be politically powerful to acknowledge this problem and to propose innovative solutions that tap the energy of citizens, like those used in Uganda in the Philippines.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: democratic reform overseas , revitalizing the left

October 29, 2007

social accountability and public work

(En route to Baltimore) "Social accountability" means various techniques for getting citizens involved in monitoring government. The World Bank has published a booklet called "From Shouting to Counting" (pdf) that provides examples. In Uganda, the government provides detailed information about how it actually spends its education funds, disseminating the data by radio and newspaper. At the same time, control over education has been somewhat decentralized. Armed with detailed information, Ugandans are able to demand efficient performance from their local schools. In more than 100 Brazilian cities, the municipal government empowers large, basically voluntary citizens’ councils to allocate a proportion of the municipal budget through a process called Participatory Budgeting (PB). And in Rajasthan (India), a non-governmental organization began demanding public records and holding informal public hearings to uncover waste and corruption.

I suspect that it would be wise to embed social accountability in a broader concept of "public work" (see Boyte and Kari, 1996). Here's a table to clarify what I mean:

| Social accountability as a stand-alone process | Social accountability as part of "public work" | |

| example | Project in Malawi in which citizens are recruited to audit public spending | Project in the Philippines in which citizens monitor the distribution of school textbooks and (when necessary) physically move them to schools |

| major analogy | Citizens as legislators or jurors | Citizens as voluntary workers |

| nature of power | Zero-sum: more for citizens means less for the state. Thus power must be granted by, or seized from, the state | Potentially expandable: by working together, citizens create greater capacity |

| intended outcomes | More efficiency and less corruption in the administration of a government program. | Defining and addressing a community problem |

| state and civil society | Two sectors that exchange information and negotiate | Lines are blurred: government employees are seen as citizens |

| options when problems are uncovered | Legal remedies (lawsuits, calling the police); public disclosure and shaming | Legal remedies and public disclosure; direct voluntary action to remedy the problem |

| accountability | By government, to citizens | In principle, by everyone to everyone |

| recruitment | Representative sample of citizens is recruited for the task of monitoring government | Members of an association take on a voluntary task. They also develop the next generation of active members |

| preconditions | Legal rights of assembly and expression; formal system for accountability | Legal rights of assembly and expression; active voluntary associations |

permanent link | comments (0) | category: democratic reform overseas

September 11, 2007

Gordon Brown on civic renewal

(from Dayton, OH) I'm a bit disappointed by the small role that themes of civic renewal and citizen participation have played so far in the US presidential campaign. But recent developments in Britain are remarkably promising. If Thatcherite conservatism could migrate from the UK to the USA, maybe we can borrow their new civic orientation.

Thus consider these excerpts from Prime Minister Gordon Brown's recent speech to the National Council of Voluntary Organisations. ...

Brown starts by depicting a set of "big challanges" that are too complex and too mixed up with personal behavior and culture to be fixed by government alone. As he says later in the speech, "When we think about how to tackle the big challenges we face it is increasingly the culture in which we live our lives that matters, our beliefs and aspirations, the values and norms that shape our goals and the boundaries that we set and are prepared to set for the way we behave in our families and in our communities."

Thus, he argues, it is necessary to tap the energies and ideas of many citizens in a decentralized way: "Britain needs a new type of politics which embraces everyone in the nation and not just a select few, a politics that is built on consensus and not division, a politics that is built on engaging with people and not excluding them, and perhaps most of all a politics that draws upon the widest range of talents and expertise, not narrow circles of power."

Brown emphasizes that we live in a time of civic innovation and idealism, even if governments and bureaucracies sometimes feel tired and overwhelmed. "And although ours is an era in which many of the traditional structures of society and association and voluntary engagement have declined, I have also seen round the country as I have visited different communities new and vibrant forms of civic life, social and community action, multi-media technologies that have transformed and are transforming the scope and nature of civic participation."

As in the United States (where community development corporations, land trusts, and other nonprofits are now significant economic actors), so in Britain, "the words voluntarism and voluntary action no longer fully capture [what is] happening daily in our communities. There are 50,000 social enterprises with a combined turnover of £27 billions. Half of the population, as we know, volunteers at least once a month. We have to reach out and connect with this new energy and enterprise and it is urgent that we do so because of the profound new challenges that I believe this country faces now and for the future cannot be solved, cannot be met by top-down solutions simply by saying, as people often did in the past, that the man in Whitehall knows best."

Brown cites crime and climate change as two examples of issues that the government cannot solve alone. The latter problem, he says, "demands that we combine international action and investment with the direct personal and social responsibility and commitment of ordinary people in every community of our country."

Although Brown calls for consensus, his position is itself an ideology (and so much the better for being one, in my opinion). He steers his way between neoliberalism and socialism: "So I do not agree with the old belief of half a century ago that we can issue commands from Whitehall and expect the world to change, nor can we leave these great social challenges simply to the market alone."

Although Brown recognizes the strength and dynamism of the nonprofit sector, he worries about its weak connection to formal politics. "In the 1950s 1 in 11 people joined a political party, today it is 1 in 88. Once political parties aggregated views from millions of people, now they need to broaden their appeal to articulate the views of more than the few. ... And this is not because politicians are necessarily as individuals less trustworthy or because they work less hard, nor does it mean the end of political parties. Party politics remains at the heart of a representative democracy, it reflects inevitable differences of values and principles and it is fundamental to citizens to have a clear choice of programmes and policies. But I believe that the evidence shows that the depths of people's concerns cannot be met by the shallowness of an old-style politics."

At this point, Brown begins to outline practical ideas for increasing citizen voice in policy. "We have already taken the step of publishing the legislative programme in draft, inviting comments and views, and for the last six months I have been discussing and working through how to do in a more consultative way that involves people in debating the issues that matter - drugs, crime, antisocial behaviour, housing development or even foreign policy issues like Iraq where there are public discussions."

The first step will be to "hold Citizens Juries round the country. The members of these juries will be chosen independently. Participants will be given facts and figures that are independently verified, they can look at real issues and solutions, just as a jury examines a case. And where these citizens juries are held the intention is to bring people together to explore where common ground exists."

Brown explains that "Citizens Juries are not a substitute for representative democracy, they are an enrichment of it. The challenge of reviving local democracy can only be met if we build new forms of citizen involvement to encourage them in our local services and in new ways of holding people who run our services to account. So we will expand opportunities for deliberation, we will extend democratic participation in our local communities."

permanent link | comments (2) | category: democratic reform overseas

August 21, 2007

the British shift to participation

While on our side of the Atlantic we struggle to promote themes of public participation (see the November Fifth Coalition for some ideas), in Britain, the new Government has fully embraced civic engagement. As Polly Toynbee writes in the Guardian:

Ministers keep saying it - the key to success in social programmes is through breathing new life into communities. Research into what works in urban renewal finds engaging the people is the only answer. On Monday the new "neighbourhood renewal action plan" is launched, designed to reach down into the heart of the poorest places, promising to rebuild communities from the bottom upwards. The word is local "empowerment".The vision of the celestial city looks something like this: parents are involved daily with schools. Churches and local groups run after-school clubs, tenants on estates control their own budgets. All local departments pool their budgets, working together to offer whatever local people want most. Mentors guide and support young offenders, aspirant businesses, struggling readers, prisoners or depressed young mothers, connecting the disconnected. Thus local government is re born as people use the rusty levers of power in their communities.

This is exactly the vision that inspires me and my colleagues. But Toynbee puts her finger on two problems. First, encouraging public participation runs exactly against the hallmark of "New Labour," which has been efficient, accountable public administration. New Labour doesn't throw money at problems or bury people in regulations. Instead, "every social programme comes with rigorous targets to be monitored ruthlessly. Every penny of public money is tied up in a public service agreement, where departments deliver or die on their Treasury contracts." There were reasons for this style of government, and it's not obvious that Labour can deliver both efficiency and participation.

Second, "there is no clamour for community involvement. It is a top-down prescription in a time when people have deserted the churches, the Rotary Club, the WI, political parties and trade unions. They don't tell the pollsters they hanker after committees, minutes and points of order."

What Oscar Wilde said about socialism is also true of civic empowerment: the problem is all those meetings. We will release a survey on October that measures Americans' appetite for public participation. I'm not going to reveal any results until then, but suffice it to say that the question of demand is important.

Toynbee suggests investing money in public facilities so that they are comfortable, attractive, and welcoming. She notes that in the early 1900s, British public buildings were much nicer and more dignified than average British private homes. Now public and nonprofit institutions are decrepit and depressing, but homes are more comfortable than ever before. No wonder people prefer to watch the telly than hang out at the community center.

Toynbee argues that financial investment in the public sector is a precondition of civic engagement. She sees this as a principle that distinguishes the left from the right (notwithstanding Gordon Brown's post-partisan rhetoric.) But interestingly, Toynbee (who stuck with Labour and refused to join the Liberal Democrats) cites Joseph Chamberlain in a favorable way. Chamberlain was a Liberal politician, not a socialist or a trade unionist. Perhaps a strategy of public investment, decentralization, civic mobilization, and state cooperation with civil society is the authentic heritage of British Liberalism; and Gordon Brown's Labour Party ought to head in that direction. In the US, we have similar traditions to draw on.

(Most Americans who visit England see medieval and renaissance sites or stay in London, so they don't understand the tremendous civic infrastructure of British provincial industrial cities in the Victorian era. Cities like Birmingham and Liverpool had public and nonprofit institutions, local pride, and social networks to rival or surpass Tocquevillian America. These institutions arose in the great age of the Liberal Party.)

permanent link | comments (0) | category: democratic reform overseas

June 11, 2004

deliberation and advocacy

Rose Marie Nierras (of the University of Sussex) and I conducted a kind of focus group today. The participants were activists from the United States, Canada, the Phillippines, India, Brazil, Mexico, South Africa, Sweden, and Denmark. Rose and I have been studying how deliberative democracy looks to people who work in social movements, especially in the developing world. This was the fourth and final day of the Deliberative Democracy Consortium/LogoLink meetings, and Rose and I have been interviewing the participants individually. Today's group discussion will give us additional data; and we will conduct several more such events in several countries before we finish the project.

We are not ready to digest our results so far, but I have a few stray thoughts: It's more difficult to mobilize lots of people for procedural reforms than for specific social causes--except when there is a dictator in the way of social progress, in which case "democracy" becomes a rallying cry. It's easier for social advocates to embrace democratization if they believe that their cause is supported by a large majority of their fellow citizens. It's harder to disentangle social causes from democratic reforms in new democracies than in "mature" ones.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: deliberation , democratic reform overseas

May 14, 2003

deliberation in Argentina

I have just spent a very interesting two days at a conference sponsored by the Institute for Philosophy & Public Policy and the Fundacion Nueva Generacion Argentina on the subject of "Deliberative Democracy: Principles and Cases." Essentially, the conference brought together four groups of experts into fruitful dialogue:

- The Fundacion sent Argentines who are deeply embroiled in their country's convulsive political crisis.

- Innovative grantmakers and aid experts talked about new approaches to development assistance that help democracy (or good governance) and civil society.

- Practitioners who organize human-scale deliberative experiments (e.g., Carolyn Lukensmeyer of America Speaks) talked about their work. Also, Gianpaolo Baiocchi contributed ethnographic research on participatory budgeting in Porto Allegre (which is turning into the Mecca for progessive and populist reformers); and Andrew Selee described participatory and deliberative experiments in Mexico.

- Several American theorists and social scientists gave papers on deliberative democracy. Jane Mansbridge argued for the significance of practice for deliberative theory, drawing some theoretical conclusions about the importance of self-interest and passion. Henry Richardson talked about the corrupting effects of being powerless, and the discipline that comes from having to make practical decisions together. Noelle McAfee distinguished three types of deliberative democracy. And Joel Siegel provided evidence that democracy contributes to economic growth in developing countries.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: deliberation , democratic reform overseas