March 15, 2011

If You Want Citizens to Trust Government, Empower Them to Govern

In lieu of a post today, here is a link to my article on The Democratic Strategist, number six in a symposium on distrust in government, organized by Demos. The previous five contributions have been helpfully diverse, but all have shared the premises that: 1) deep distrust is an obstacle to progressive politics; 2) distrust is not simply a result of anti-government rhetoric and hostile media but also flows from people's authentic experiences of government; and 3) progressives can reduce distrust by governing differently. My prescription is unique in its emphasis on enlisting the people in governance.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: revitalizing the left

August 31, 2010

what happened to the new Obama voters?

Project Vote is pushing an important line of argument. They say that our policy debate is distorted because the media is fascinated with the Tea Partiers ("Who are they? What do they want? Will they affect elections?") and is ignoring the huge number of new voters who turned out in 2008. Those new voters tended to be younger, less wealthy, more racially diverse, and more politically progressive than the typical US electorate, and they won a national election. If the press today would constantly ask, "Who are they and what do they want?" the whole policy debate might be quite different.

Lorraine C. Minnite writes, "heading into the 2010 congressional midterm elections the views of traditionally under-represented groups who were mobilized in record proportions in 2008 have been drowned in tea." See her "What Happened to Hope and Change? How Fascination with the 'Tea Party' Obscures the Significance of the 2008 Electorate" (PDF) and a soon-to-be released Project Vote survey.

Reporters focus relentlessly on predicting the next national election. (I've quoted the former CNN political director, Tom Hannon, saying, "the most basic question about [an] election ... is who's going to win.") From that perspective, it's somewhat rational to focus on the Tea Partiers and not the recent Obama voters. Current polls that screen for likelihood of voting in 2010 suggest that the electorate will shift rightward again in 2010 because of who turns out. Thus, if you want to predict the next election, it makes sense to focus on the new conservative voters. Two important caveats, however, will probably be missed. First, the Tea Party will not represent the median voter, who will be moderate; and second, the electorate will probably swing back leftward in 2012.

Assuming that the media (and the blogosphere) continue to focus on predicting the 2010 election, the only way to shift the discussion is for progressive constituencies to threaten to vote. They need to tell pollsters that they are excited to vote, and they need to take public steps--like marches and protests--that indicate mobilization. That's how the game is played right now, and they're not playing well.

But the game isn't satisfactory. "The most basic question" about politics is not "who's going to win." The most basic question is: What should we do? Although the press can't answer that for us, they could provide information relevant to our decisions.

From that perspective, "Who will win the next election?" shouldn't matter much. At most, it should have a modest impact on our strategic plans, but it should not cause us to change our own goals. (Thus the relentless focus on the horse race is problematic.) Who voted in the last election is perhaps a bit more relevant, because the winners presumably have some democratic legitimacy as the current governing coalition. Who might vote if we changed our politics is more interesting, because it invites us to consider a wider range of strategies. I'll be looking forward to the Project Vote survey for that final reason--it will suggest ideas about how we might be able to mobilize new progressive voters with new progressive policies.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: revitalizing the left

December 17, 2009

what hard looks like

Remember on Inauguration Day, when fans of Barack Obama felt admiration for the new president as a person--mixed with a foreboding sense that things would soon become difficult for him? That's the sense I felt on the National Mall last January. But what did people imagine that "difficult" would look like? Did they think that poor Barack would have to stay up late every night working on legislation? Or that he would consistently propose policies that we support and be criticized by people we abhor?

If those were our thoughts, we were naive about politics and American society. Governing under difficult conditions means exactly the kind of compromise and negotiation that we see today--that's what "hard" means. I've been critical of the administration, and I will gradually raise my bar of expectations over the coming years. Criticism is appropriate--helpful, even. But if anything disappoints me, it is not the choices of the administration. It is the sense that we were entitled to be handed "change" by the new president after we had finished our job by electing him last November. He always said quite the opposite--that the burden was going to fall on us.

I keep hearing friends and colleagues shake their heads in disappointment that the president has let us down. I want to shake them and shout, "What have you done lately?" I'm sorry, but I missed the millions of liberals marching though Washington to demand a single-payer health system. I noticed the tea party protesters, the insurance lobbyists, and Fox News. I watched public support for health care reform fall to the low thirties in recent surveys. I have not seen much counter-pressure. True, Organizing for America has been weak so far--but since when did liberals count on an incumbent president to organize a grassroots advocacy effort to put pressure on himself from the left? That's our job.

These are the specific policies that most seem to disappoint the left:

- The health reform bill, which Howard Dean and others are saying should be scuttled. It's a compromise, and the process of legislative negotiation is ugly to watch. Joe Lieberman should be ashamed of himself, and the filibuster should be overturned. But this bill will be the most ambitious piece of progressive legislation since the 1960s, representing $900 billion in subsidies for lower-income people, paid by upper-income people, along with significant regulatory reforms. To pass this through a fractious body of 535 members while under unrelenting corporate pressure, during a recession, after the public has been asked to bail out banks and car companies, is an almost unbelievable achievement. The public option was, in my view, always an ideological proxy issue and not an important reform for disadvantaged Americans.

- The stimulus, which Paul Krugman and others argue should have been much bigger. An economist will also tell you--if you're stranded on a desert island with canned goods--to assume that you have a can-opener. In the real world, the government has only actually spent 30% of the appropriated stimulus funds so far. The feds don't have a magical ability to push money out the door. I am not convinced that faster stimulus spending would have been possible.

- Afghanistan, which many people are analogizing to Vietnam. The first point to note is that the president campaigned with a consistent commitment to "winning" in Afghanistan--so he has hardly betrayed his voters. The second point is that the available choices are all unpalatable. If we retain the current level of troops, we and the Afghans will just bleed slowly. If we withdraw, there will be a nightmare, in humanitarian as well as security terms. I am pessimistic about the surge, but I acknowledge that it creates the chance for some kind of multilateral deal before we leave.

- Wall Street reform, which strikes liberals as thoroughly inadequate. Maybe so, but Congress now seems poised to pass comprehensive financial reform legislation. That's not easy to accomplish given the "privileged position of business," especially in a weak economy.

- Human rights and civil liberties, on which the administration's policies seem too close to its predecessor's. There is definitely ground for criticism here. But Guantanamo is emerging as a symbol of failure, and that reinforces my view that Obama's leftist critics are naive. What are we supposed to do--open the doors of Guantanamo and let the prisoners go wherever they want? Said Ali al-Shihri was released and is now leading Al Qaeda's deadly efforts in Yemen. We cannot try people in criminal court if they are basically prisoners of war. And we can't repatriate them if their home countries are likely to torture and execute them. Of course, Guantanamo must be closed, but it is better to do this carefully and right than quickly.

Again, my point is not that the administration is amazingly admirable or that Barack Obama should be our personal hero. My point is that nobody can accomplish "change" for us. There are plenty of ways to engage, and if you don't use at least one of them, you have no business complaining.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: revitalizing the left

October 26, 2009

an alternative history of 20th century liberalism

From the 1940s to the 1960s, American liberalism had everything that an ideology should: millions of active adherents, heroes and leaders, supportive organizations (from the AFL-CIO to the ACLU), legislative victories and an unfinished legislative agenda, empirical theories and supportive evidence, and moral principles. The principles could be summarized as the famous Four Freedoms, but we could spell them out a bit more, as follows: The individual liberties in the Bill of Rights trump social goods, but it is the responsibility of the national government to promote social goods once private freedoms have been secured. The chief social goods include minimal levels of welfare for all (the "safety net," or Freedom from Want), equality of opportunity (achieved through public education, civil rights legislation, and pro-competitive regulation in the marketplace), and consistent prosperity, promoted by Keynesian economic policies during recessions.

These ideas had empirical support from sociology and economics and could be developed into a whole philosophy, as John Rawls did in The Theory of Justice (1971). Rawls' theses of the "priority of the right to the good" and "the difference principle" really summarize the whole movement.

Rawls hardly mentions modern history or policies, but he cites and argues with major theorists, such as Kant, Mill, and John Harsanyi. So we could tell a story about American liberalism--understood as a set of ideas--that emphasizes its origins in theoretical debates. Franklin Roosevelt constructed a monument to Thomas Jefferson because he wanted to show liberalism's debts to that enlightenment philosopher; the inside of the Jefferson Monument is bedecked with quotes favorable to the New Deal. Other parts of the liberal synthesis can be traced back to Jefferson's less popular contemporary, Hamilton. Keynes, Brandeis, Gifford Pinchot, and Felix Frankfurter were more proximate intellectual sources. We could understand the New Deal as a development of Victorian liberalism that added arguments in favor of federal activism to combat monopoly, environmental catastrophe, and the business cycle. A story of liberalism as a set of principles, theories, and proposals implies that a revival will require new ideas and a new intellectual synthesis.

But I would tell the story an entirely different way--as the "scaling up" of concrete examples and experiments that were undertaken originally in a highly pragmatic vein. Think, for example, of Jane Addams in 1889. She is a rich and well-educated person who has no possibility of a career (because she is a woman) and who is deeply troubled by poverty in industrial cities. She is impressed by the concrete example of Toynbee Hall, a settlement house in London. She and Ellen Gates Starr move into a house in a poor district of Chicago without a very clear plan for what to do. They launch projects and events, many of which have a "deliberative" flavor--residents come together to read challenging books, discuss, and debate. Out of these discussions come a kindergarten, a museum, a public kitchen, a bath house, a library, numerous adult education courses, and reform initiatives related to politics and unions. Some 2000 people come to Hull House every day at its peak, to talk, work, advocate, and receive services.

In the 1920s, when progressive state governments like New York's start building more ambitious social and educational services, they literally fund settlement houses and launch other institutions (schools, state colleges, clinics, public housing projects, welfare agencies) modeled on Hull House and its sister settlements. Then, when Roosevelt takes office and decides to stimulate the economy with federal spending, he creates programs like the WPA that are essentially Hull House writ large.

Here, thanks to Nancy Lorance, is a WPA-funded recreation worker singing with a group of children who live in the Jane Addams public housing project in Chicago during the New Deal:

The combination of culture, education, public investment, and the very name "Jane Addams Housing Project," pretty much sum up this story of American liberalism as discussion, followed by experimentation, followed by public funding. At the heart of the ideology, so understood, is not a theory but a set of impressive examples.

This is not to deny the intellectual achievement of the movement--Jane Addams, for instance, was an extremely learned and insightful writer. But it suggests that intellectual reflection follows practical experimentation, not the reverse. Even John Rawls can be read as a defender of the concrete reforms of 1930-1970, although he never mentions them. If you find The Theory of Justice persuasive, it's not because you have imagined yourself in the "original position" and reasoned your way to a set of principles that would apply anywhere. It's because you think that a government can make a positive difference by guaranteeing the First Amendment, taxing people to a substantial but not overwhelming extent, and spending the proceeds on education, welfare, and health. If you agree with those theses, it's because of what the actual government has done. The basis of The Theory of Justice is thoroughly experimental.

Today, we have different challenges from those that FDR's America faced in 1932. Climate change, terrorism, de-industrialization, crime, the lack of social mobility over generations, the close association between economic security and educational attainment, and rising health-care costs would make my list of our challenges. If it's right to see mid-twentieth-century liberalism as an expansion of pragmatic experimentation, then we should be looking to today's charter schools, innovative clinics and health plans, land trusts and co-ops, and socially minded business for the concrete cases that merit expansion. We are less in need of major theories than of what Roberto Mangabeira Unger calls a "culture of democratic experimentalism."

permanent link | comments (1) | category: revitalizing the left

September 21, 2009

assessing ACORN

ACORN (Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now) is the epicenter of today's political struggle. It was already a target of angry criticism during the 2008 election because of its radicalism and its links to Barack Obama--and perhaps because it is one of the only effective interest groups for poor people. (It claims 400,000 families in its membership.) Both houses of Congress recently passed bills to strip ACORN of federal funds after a video surfaced in which ACORN staff were shown providing illegal assistance to actors pretending to be, respectively, a pimp and a prostitute. ACORN replied that the behavior caught on tape was unacceptable but that many other staffers had refused to help the actors--some even called the police--and that the tape may have been doctored.

Because of ACORN's sheer size and its symbolic importance, we need to reach fair and informed judgments about it. Maybe Democrats and liberals should throw it off the bus, or maybe we should defend it. I am cautious about reaching any judgment, because I know that it's hard to make a fair and accurate assessment of a large organization that is the target of unrelentingly hostile scrutiny. One problem with the "gotcha" video (apart from its hostile motivation), is its lack of reliability. Who knows, for example, whether the discarded video from other encounters would make ACORN look very ethical? And perhaps you could get similar footage if you traveled around the country trying to entrap staff from the Red Cross or the Veterans of Foreign Wars. The evidentiary value of the video is low.

Thus it's with deep uncertainty and humility that I confess my own misgivings about ACORN. There was, first of all, the astounding news that the board covered up a $1 million case of embezzlement to prevent embarrassment. I blogged about that--as an angry former donor whose money had been stolen--and I did receive a personalized and very strongly worded apology. The apology made a difference to me, but the original scandal reinforced my feelings about ACORN's worldview. ACORN thinks of poor people as victims, and itself as a victim because it stands with them. There are villains who are out to get the poor, and ACORN is good because it is on their side. That kind of attitude can excuse bad behavior and cover-ups. More than that, it can cause you to underestimate the capacities of poor people and opportunities for collaboration.

A classic ACORN event displays the victimization of poor people and the wickedness of some rich and powerful group (who then become even less likely to collaborate). For instance, I once described an ACORN protest against federal welfare policy. The angry crowd that ACORN assembled shouted down the sole member of Congress who chose to address them, Rep. Charles B. Rangel of Harlem, demanding that he answer their questions and meet with them in New York City. One of the rally's organizers (a Harvard graduate) explained: "Most of the crowd are people living with the reality of fairly extreme poverty in their own lives, and they are rightly angry."

The organizers of this protest apparently believed that they could speak for poor people, whose main need was more federal welfare spending. Their strategy for winning such aid was to parade welfare recipients before Congress and the press, emphasizing their deprivation and anger. (They also displayed the political naivety and weakness of these people.) The protest organizers implied that anyone who did not completely endorse their demands was their enemy. And of course they failed completely.

In contrast, community organizers such as the Industrial Areas Foundation like to build up the confidence, skills, and power of poor people and make allies out of any powerful leaders and institutions who will cooperate. Their goal is to work with the powerful as equals, with mutual respect and accountability. Time and time again, the latter kind of organizers report that ACORN is a major problem.

For instance, in Community Organizing: Building Social Capital as a Development Strategy, Ross Gittel and Avid Vidal focus on LISC (the Local Initiatives Support Corporation), which supports collaborative community development in poor areas. They write:

- After program activities began in Little Rock, the local coordinator tried to reach out to ACORN and develop a working relationship but was largely unsuccessful. ACORN was never ideologically comfortable working with LISC and was highly doubtful about the potential efficacy of the consensus organizing approach, which contrasted with their own confrontational tactics. ACORN tried at times to undermine LISC's efforts (e.g., claiming that LISC groups were "selling out to corporate interests"), but was largely unsuccessful.

Again, in Streets of Hope: The Fall and Rise of an Urban Neighborhood, Peter Medoff and Holly Sklar tell the story of the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative in Bostons South End. They devote a whole section to "friction" with ACORN. They write, "By the time ACORN first expanded into Massachusetts in 1980, it had already developed a reputation among progressive organizers and funders for not working in coalition with other organizations. In Boston, it was seen as invading the turf of Massachusetts Fair Share."

In the 1980s, ACORN set up a "tent city" in vacant, city-owned land to pressure Boston to build affordable housing. "DSNI members were angry not only because ACORN, seen as an outsider to the neighborhood, had focused on Dudley Street without first contacting DSNI, which had been so carefully structured to empower residents and break the pattern of outsider-agency domination. But also DSNI ... had successfully negotiated with the city to stop disposing of vacant land until the neighborhood was able to complete a comprehensive neighborhood development plan and exercise community control." (Medoff and Sklar proceed to describe "angry exchanges" and charges that ACORN members pretended to be from DSNI when they canvassed for money.)

These are anecdotes that depend on testimony from people who have struggled with ACORN. Maybe ACORN's side of each story would be convincing. But I could multiply these examples, and they add up to an indictment. I think partisan Republicans are attacking ACORN with poor motives and unethical methods. They dramatically exaggerate its funding and impact, when it appears to be in pretty rough shape. But there is a valid critique from the left. The two critiques are related because the same tactics that antagonize ideological conservatives also disempower poor people at the grassroots level and disrupt progressive coalitions. I wouldn't throw ACORN off the bus, but I am for strengthening the alternatives.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: revitalizing the left

August 31, 2009

what the public option means about our politics

The best reason to create a public health insurance option is to increase competition in the health insurance market and thereby lower premiums. No one can know how much money a public option would save, but the idea seems worth trying as an efficiency measure.

It is being treated as much more than that--as the central battle of the summer and perhaps of the whole 111th Congress. Some liberals (an explicit example is Paul Krugman) want to show that assertive governments can do good--thereby debunking modern conservatism, which holds that governments are the problem. Passing a public option would demonstrate that a ruling majority in America today supports activist government; the success of the new policy would then increase support for such activism. As Mark Schmitt observes, the origin of the public option was not research into which policy would cut costs, but rather a political strategy to get a victory for expansionist liberalism.

For that very reason, conservatives want to defeat the proposal. Defeat would demonstrate that there is no pro-government ruling majority in America today; it would also allow opponents to argue against the evils of the public plan without the risk that it might work in practice.

This kind of proxy battle is common today. For example, charter schools are promoted by libertarians, who want to demonstrate that choice can improve quality even in an area traditionally run by the state, and by moderate liberals, who want to show that the public sector can innovate and therefore doesn't deserve to be cut. Charter schools are opposed by some traditional liberals who think that market-type competition is overrated and who want to draw the line at the schoolhouse. The decision whether to turn a given school into a charter thus becomes an ideological proxy battle rather than a rather complex, nuanced, fundamentally local question about which governance structure would work best in each situation. (See my analysis here.)

There are advantages to ideological politics. We must simplify by applying broad principles, or else the complexity, variety, and nuance of the world is overwhelming and we cannot act at all. Voter turnout rises when there is more ideological conflict because it is easier to engage when the lines are sharply and simply drawn. Ideological strategists, such as the libertarians of Victorian England and the activist liberals of the New Deal, have sometimes achieved great things.

But the drawbacks of ideological politics are obvious: oversimplification, suppression of worthy alternatives, manipulation of voters who aren't attuned to the ideological game, and a tendency to confuse means with ends. We see these problems in today's health care debate. The true goal for progressives is to provide all Americans with affordable health insurance. There are crucial provisions in the main Congressional bills for that purpose--notably, subsidies for low-income Americans and regulations to protect people who have pre-existing conditions. The details of these provisions are essential. Who is eligible for how much financial support are the most important questions for poor people. They are not, however, the focus of the great national debate--for two reasons. First, poor people are not organized or influential. Second, subsidies are not an ideological proxy issue. We already subsidize health care--it's unexciting (but very important) to propose spending more.

The public option should be a means (a mechanism to cut costs and therefore make it easier to insure everyone), but it is becoming the end because of its symbolic role in ideological politics.

Meanwhile, liberals don't seem interested in the potential of private co-ops, if appropriately designed and funded. That's because co-ops have been portrayed simply as a compromise between liberals and conservatives, and therefore as a disappointing outcome for those--on both sides--who want an ideological "win."

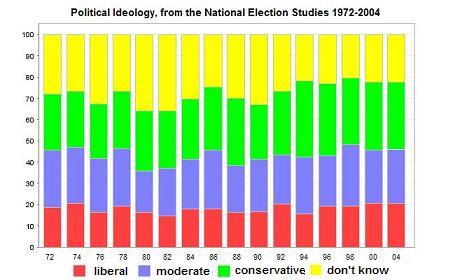

I suspect that the health care debate is less engaging for average Americans than it should be because it has turned into an ideological proxy debate that makes most sense to the "base" on both sides. By the way, the conservative ideological base is usually about twice as big as the liberal ideological base--26% called themselves conservatives versus 15% who identified as liberals in the 2004 American National Election Survey.

I noted above that ideologies can encourage participation by providing comprehensive worldviews that make decisions easier. But only certain kinds of ideologies work for that purpose. A vital ideology needs an impressive story arc, beloved and talented current leaders, moving examples, strong networks and organized backers, opportunities for grassroots engagement, and a coherent theory. New Deal liberalism had all those, at its peak. Paul Krugman's ambition is to resurrect statist liberalism as a movement. Maybe that's possible, but it certainly hasn't happened yet. Thus I am not at all surprised that most people feel left out of the ideological proxy war that is taking place among political elites and strong partisans. I am also not surprised that conservatives are winning the health care debate--it is a proxy battle, and they have more true believers. If it could be about how to provide the best possible health care for all Americans, it would be a different story.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: revitalizing the left

July 29, 2009

tactics, wonkery, values

Back in 2004, I wrote a long post on this blog, arguing that the problem for the left was not bad tactics, nor a lack of resources, but a lack of positive vision. This was part of the argument:

In 2004, the most exciting new participants in the political debate have been independent bloggers. But the major bloggers on the Left—people like Josh Marshall, Calpundit's Kevin Drum, and Markos Moulitsas Zúniga of the Daily Kos—strike me as strictly tactical thinkers. That is, they assume that the goal is to defeat George W. Bush, and they look for ways to score points against him. He is hypocritical one day, misguided the next. I thoroughly agree, yet I don't see any basis for a new direction in American politics. Their strategy is to make the president look bad, elect a replacement, and hope that he comes up with new ideas. If there are more creative leftish thinkers in the "blogosphere," I don't know who they are. This void suggests to me that the Left is weak today because of a lack of tough and creative thinking, not because good "progressive" ideas are being suppressed by the mass media.

My post triggered thoughtful rebuttals by Mark Schmitt, Matthew Yglesias, and others.

I remembered this exchange recently when it occurred to me that Yglesias and other skillful left-of-center bloggers have become policy wonks. I spent 15 years in a school of public policy, yet occasionally even my eyes glaze over when I read Yglesias on transportation or Ezra Klein on health care. No one could rightly say that these people lack ideas about what should be done. They are as substantive as can be--as well as talented writers.

So perhaps when the Democrats were "out," bloggers on their side of the aisle were focused on getting them back "in"; and once Democrats won elections, the bloggers turned to policy. That would be a happy story and would make me apologize for my implication that the left blogosphere was superficial in 2004.

Except for one thing: I don't divide politics into tactics and policy. There is a crucial third element, which is the creation of some kind of moving storyline that embodies core values. I think that's much more important than getting one's policy proposals right, and it was a conspicuous failure in '04. An argument about values and a narrative arc are what Barack Obama contributed to the left in '08. The particular positions that he took could be wrong, but in any case, they do not seem to attract much attention or support in the liberal blogosphere. For instance:

Government cannot solve our problems; citizens must do that through their own work.

Our relationships are broken because of excessive confrontation and distrust, and we need to work together across differences.

We must take more moral responsibility for ourselves and our children.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: revitalizing the left

March 4, 2009

the worm turns

Several months before the 2004 election, I wrote a post entitled "what's wrong with the left, and what we can do about it?" I criticized the belief that Democrats lost elections because Republicans had unfair advantages or played the game better. At that time, many liberals were blaming Fox News and Karl Rove for their problems and were developing a presidential election strategy that revolved around better "messaging." I suggested (as a thought-experiment) that we imagine what Democrats would say to the American people if they had two hours of uninterrupted time. Then all the machinations of spinmeisters and biased media would be irrelevant. I claimed that Democrats would have nothing inspiring to say about the future of America. I then proposed several directions that could be more engaging: a theme of stewardship; a commitment to bold, persistent experimentation; a good-government reform platform; and an agenda of helping everyone to be creators and contributors to the commonwealth.

When that year's Democratic Convention was all about John Kerry's macho biography and the stupidity of George W. Bush, my heart sank (although a speech by the new Senator-Elect from Illinois moved me).

But political history has since moved with remarkable speed. The Obama Campaign was inspirational and forward-looking. Themes of stewardship, experimentation, good government, and creativity/service were prominent. An additional issue is now paramount and creates an urgent need for deeper change: the economic collapse. The recovery effort opens great opportunities for better stewardship, transparency, reform, and public work.

Meanwhile, Republicans are debating whether they should be openly saying that they want Obama to fail. (I remember private conversations about Bush in 2002-4 that had a similar flavor.) When your critical "message" about your opponent is your focus, you are in deep trouble. The lack of intellectual vision on the right now matches or surpasses what we saw on the left just four years ago.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: revitalizing the left

November 23, 2008

work, not service

Candidate Barack Obama, July 2:

- "I will ask for your service and your active citizenship when I am President of the United States. This will not be a call issued in one speech or one program—this will be a central cause of my presidency."

President Elect Barack Obama, Nov. 22:

"We'll put people back to work rebuilding our crumbling roads and bridges, modernizing schools that are failing our children, and building wind farms and solar panels; fuel-efficient cars and the alternative energy technologies that can free us from our dependence on foreign oil and keep our economy competitive in the years ahead."

These two statements seemed to be about different topics. The first was an argument for increasing the number of federally-funded civilian "service" slots to as many as 250,000; the second announced a plan to create or save 2.5 million full-time jobs, mostly in the private sector. The first makes us think of unpaid volunteering or short-term, low-paid positions in nonprofits and government agencies. The second conjures images of permanent, salaried employees in labs or on corporate assembly lines. "Service" is about personal values: patriotism, civic virtue, caring, or helping--a "thousand points of light." Job programs are about macroeconomic growth and take-home pay for hard-working Americans.

I think the two ideas should be combined, and "work," not "service," should be the hallmark of "active citizenship" in the Obama Administration. I have never been very enthusiastic about service on its own. It is marginal--a lower priority than one's job or family, something to do after work, on special occasions, or during adolescence or retirement. People involved in service tend to be congratulated and thanked regardless of their impact, whereas workers are expected to get the job done. Service makes the recipients look weak and needy, whereas work is an exchange for mutual benefit.

Service programs, such as Americorps, can certainly be great for the volunteers and the community. But that is because they provide work, albeit with a strong and commendable element of civic education for the workers. Meanwhile, a full-time, paid job in the private sector can also be "active citizenship," if we allow, support, and encourage the employees to work on public problems (such as modernizing schools or building wind farms).

As I wrote here recently, the Obama Administration can restore a New Deal version of liberalism whose central task is to put people to work for the public good. Private sector jobs are part of that, especially if federal subsidies, incentives, or mandates steer these jobs toward public purposes. Public sector careers at every level, military service, and civilian service programs such as Americorps are also important. So is an educational system that prepares people for public work. Students will need a strong dose of civic education so that they can discuss and define the public problems that they choose to address as workers. It is not enough to prepare them for an increasingly competitive job market; they also need to shape that market for public purposes.

I would admire this form of liberalism at any time, because of its ethical conception of the citizen as an active, creative agent. But today seems an especially appropriate moment to bring back the New Deal conception. We need jobs programs for standard economic reasons; and our newly elected president has pledged to make "active citizenship ... a central cause."

permanent link | comments (0) | category: Barack Obama , revitalizing the left

December 31, 2007

the Obama "theory of change"

Mark Schmitt’s essay on Senator Obama has been very widely cited (and should be applied to politicians other than Obama himself). Schmitt argues that, as president, Obama might win legislative victories by treating conservatism as a legitimate philosophy and presuming that his opponents honor the same basic values that he does--e.g., health care for all. This assumption would put Republicans in a difficult position if the evidence favored progressive proposals. Obama’s conciliatory and deliberative style might win over a few Republican senators, Schmitt says, and that is essential if Democrats want to pass legislation.

I actually thought these points were obvious all along, but I’m grateful to Schmitt for using his authority to spell them out for progressive readers. The opposite of Schmitt’s position is being argued by "Kos" in Newsweek and by Paul Krugman in the New York Times. They recommend blaming anti-government conservatism for our major problems, tying all Republican candidates to that ideology, and trying to create a large pro-government majority. Their best argument is that conservative ideas are now fairly unpopular, according to surveys. However, they overlook the following points:

First, Americans do not think ideologically. For instance, few Americans have been interested in the ideological differences between Saddam Hussein and Osama bin Laden, even though the two men were diametrical opposites. Often, less than half of respondents to the National Election Studies are willing or able to place the Republicans to the right of the Democrats on an ideological spectrum. In discussions of local issues, according to Nina Eliasoph's research, Americans avoid ideological interpretations. And our own focus groups of college students found deep resistance to all ideologies. Therefore, it would be very hard to blame recent failures on conservatism, rather than George W. Bush personally.

Second, adopting a civil and deliberative style is a good strategy for winning elections. Liberal bloggers have been arguing that only elites, especially The Washington Post editorial board and David Broder, admire bipartisanship and civility, whereas ordinary Americans don’t care about it. These bloggers have been hanging around with angry Democrats and have not been talking to average Americans or reading the scholarly literature on political opinion. Americans are hostile to partisanship and ideological disagreement--excessively hostile, in my opinion. Their aversion to sharp disagreement hampers our politics, in some respects. But they really don't like ideological conflict.

Third, even if Americans are saying that they support somewhat more active government, there is a deep vein of public suspicion about Washington and the federal government. That suspicion is fed by the idea that Washington elites are angry, divided, uncivil, and prone to exaggerate their differences for tactical advantage. Why should you entrust thousands of your dollars to Washington to cover your health insurance if the people who run the place seem to be constantly squabbling, and each half of Congress says that the other half is wicked and foolish? Progressive policy requires public trust in government, and we won't have trust in government until leaders adopt a civil and dignified tone.

Fourth, I do not accept the diagnosis that all our major problems arise from anti-government conservatism. Kos, for example, blames the Katrina disaster on FEMA director Mike Brown, and explains Bush's choice of Brown as a symptom of the administration's "government-busting ideology." There is some truth to this, but I think the Katrina tragedy exemplifies other truths as well. The Army Corps of Engineers did damage over many decades, not because of anti-government ideology but because of managerial and technical arrogance (and old-fashioned earmarking and logrolling)--which are the dark side of the New Deal. Meanwhile, local public institutions, such as the New Orleans schools, were in calamitous condition, partly because of low budgets but partly because of extremely poor management. Yet the leaders of New Orleans were Democrats. If not all our problems are due to "government-busting ideology," then it will be hard to convince people that they are.

Fifth, a close look at the Republican Party reveals a loose coalition, not a tightly organized national machine. It's easier than Kos thinks to pick up Republican votes, and harder than he thinks to tie the whole party to a single ex-president. The best way to make Republicans feel solidarity is to try to lump them together as enemies of decent government.

I pass over a sixth reason--our ethical obligation to presume that our fellow citizens have decent motives until shown otherwise--for fear that that will make me look naive.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: Barack Obama , revitalizing the left

November 5, 2007

social accountability in the USA

In Paris last week, I met a senior minister from Uganda who said that not many years ago, 83 percent of Uganda's education budget was wasted or stolen--not spent on education. I also met a Filipino activist who said that in his country, textbooks were often stolen or lost before they reached classrooms. Both countries have achieved enormous improvements by involving citizens in monitoring and assessing school budgets and administration. According to independent evaluations, 80 percent of education funds now reach schools in Uganda, partly because the money is tracked by citizens.

It occurred to me that in the District of Columbia, about 71 percent of the education budget is not spent on schools. Some of it may be properly used for such purposes as special education. But most of the 71 percent is lost in the downtown bureaucracy. The Washington Post has printed photos of stacks of textbooks that were never distributed to schools; electronic equipment is routinely delivered without software or support. These statistics and stories are very reminiscent of Uganda and the Philippines, and indeed of most of the world.

The obvious question is whether we could use public participation in the US as a tool to reduce serious corruption and waste. This would be a great achievement because ...

1. One of the worst sources of disadvantage in our society is the dramatically unequal quality of education. An obvious way to improve education for Washington's least advantaged students would be to seize some of the $7,200 per student that is currently being used/wasted in the downtown bureaucracy so that it could be spent instead on smaller classes and better facilities.

2. Getting the public involved in accountability might shift the attention away from test scores and toward administration. Today's high-stakes tests are supposed to motivate teachers and students to work harder and more effectively--that is the main strategy for improving education. When students fail the tests, we start to wonder whether public schools can possibly achieve success (or whether our kids can possibly succeed). If citizens could audit or review the performance of their schools, they might shift the pressure away from teachers and students, who, after all, receive less than 30 percent of the budget in DC. Citizens might conclude that the marginal impact of reforming central school systems would be much greater.

3. Public participation would be an alternative to the main accountability measures that are currently used or contemplated in our schools today. We test kids and punish them for failing; and we allow parents to take their kids out of schools. In Washington, roughly half of the student body has already left, either for the suburbs or for charter schools; but we don't see better performance in the public system--nor are the charters very successful. Maybe it would work better to get citizens directly involved in school reform.

4. Students could help to monitor their own schools, which would be a powerful form of civic education.

5. I believe that the Achilles heel of the American left is the poor performance of public institutions, such as the DC Public Schools. At some level, all of us--including left-liberals--know that such systems are deeply flawed. We lose political struggles, not because Americans love corporations, nor because voters are blind to social needs, but because they don't believe that public institutions are effective and trustworthy tools. It would be politically powerful to acknowledge this problem and to propose innovative solutions that tap the energy of citizens, like those used in Uganda in the Philippines.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: democratic reform overseas , revitalizing the left

August 15, 2007

opportunity economics and civic participation

The Hope Street Group is an organization founded by young business people who believe in growth, innovation, and opportunity, but do not believe that the current economic system provides opportunities either adequately or fairly. They favor more investment in human capital, reform of taxation and financial markets, and programs to give people second chances at entrepreneurship. Hope Street Group has laid the groundwork for effective political action and will soon be better known thanks to a $1 million Omidyar grant.

I am a member of HSG. I know there are debates about whether GDP growth is an adequate measure of progress, and about whether we can achieve social justice through investments in human capital (rather than changing the bargaining power of labor versus capital). I have nothing original to contribute to those debates, and I'm agnostic about some of the key questions.

But I believe that democracy and civic participation work better when people have a sense that the pie is expanding, and specifically, when people believe that there can be more for all if we cooperate voluntarily. There is a powerful, optimistic kind of populism that says: We can make wealth, and everyone can be better off, but we need to make sure that everyone is included in productive work. This is much better than the kind of populism that presumes there is a fixed quantity of goods, of which the powerful have taken more than their fair share. Optimistic populism promotes public investments in education and infrastructure, whereas resentful populism assumes so much distrust that it ultimately undermines public programs. Resentful populism also generates bad politics: division, hyper-partisanship, retreat into interest groups, and ultimately demobilization; whereas a populism of abundance encourages dialogue, participation, innovation, and creativity.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: populism , revitalizing the left

August 13, 2007

"vertical farms" and the new political economy

Since the Industrial Revolution, fossil fuels have reduced human--and animal--drudgery. This has generally been a blessing, although we are now in danger because all that burned carbon is messing up the global climate. (And wars have been fought over oil.)

Since the Industrial Revolution, fossil fuels have reduced human--and animal--drudgery. This has generally been a blessing, although we are now in danger because all that burned carbon is messing up the global climate. (And wars have been fought over oil.)

The blessing of carbon is certainly a mixed one nowadays for older industrial cities like Baltimore, Detroit, or my hometown of Syracuse, NY. You can think of a city as an economy, with imports and exports. Energy is a major import; and we should count not only the electricity, oil, and gasoline that is literally moved into the city, but also the energy components of food, clothing, waste processing, and other necessities.

Fossil fuels have replaced work, but there is not enough rewarding work left in our older cities. The cities have to pay, somehow, for the fuel they import. The best way would be to produce exports, but manufacturing is cheaper in the developing world, and the knowledge economy belongs to people with excellent educations. The old plants lie empty--like Sparrows Point, near Baltimore, which once employed 30,000 people in steel and shipbuilding. The biggest employers in Baltimore City today are the government and private health and education facilities: together, they provide 165,000 out of 350,000 total jobs. Those positions are subsidized by state and federal taxes, but at insufficient rates. You could almost say that Baltimore purchases its fossil fuels and other necessities using Medicare, Medicaid, Title One Education funds, and state aid to schools--all funded by taxpayers who have little love for the inner cities. (I mention Baltimore because it's nearby, but the same is certainly true of Syracuse, New Haven, and other cities in which I have lived.)

The most appealing alternative I can think of is to replace fossil fuels with rewarding human labor that must be done on-site and cannot be outsourced. That is a tall order, especially if we expect the labor to be both rewarding and accessible to people without college degrees. But there are glimmers of hope. I love the idea of vertical farms that would produce hydroponic fruits and vegetables right in the city, using solar power, waste water, and skilled human labor instead of fossil fuels. Think of the nutritional, environmental, educational, social, and even aesthetic advantages if we could pull this off. (The picture is a design by Chris Jacob.)

permanent link | comments (0) | category: revitalizing the left

August 1, 2007

Feingold and La Follette

On Monday evening, I went to a party to celebrate my friend Sandy Horwitt's recently released book, Feingold: A New Democratic Party. I haven't read the whole book yet, but it's very engaging. I share Sandy's view that Senator Russ Feingold is a fitting successor to Senator Robert M. La Follette, Sr., who held the same seat a century ago. La Follette is the hero of my New Progressive Era, and I wrote quite a lot about him that didn't make the final cut. I spent some time with his papers and read most of the major studies of him. La Follette was a true hero, but he was a tragic hero, most of whose causes failed. The reason, I think, is that he never resolved some fundamental dilemmas of modern democratic politics: how to make government effective without making it technocratic; how to mobilize people for popular reform without reducing their capacity to deliberate and form their own views; how to appeal to common interests without losing sight of the particular interests that make us human; how to separate the public sector from private money without shielding government from innovation; how to retain the spirit of the neighborly community in a mass society.

On the basis of Sandy Horwitt's book, it appears that Senator Feingold is a serious student--and emulator--of La Follette. The modern Senator has the same moral compass as Fighting Bob. He is reacting to the current war much as La Follette responded to World War One, and he abhors G.W. Bush much as La Follette denounced Wilson. (Those two presidents are similar, I've argued.) Feingold is as independent as the founder of the Progressive Party was. But I don't think that Feingold, or anyone in our time, has resolved the problems of mass democracy that arose at the beginning of the 20th century. His agenda of political reform lacks a large and passionate constituency, and that's because of the atomization and technical rationality of modern society. Sandy evokes the small-town Wisconsin values that shaped both La Follette and Feingold (many decades apart), but he doesn't say--because nobody knows--how to make those values salient in a nation of 300 million.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: revitalizing the left

June 13, 2007

a new progressive era?

Tomorrow, I'm presenting at the Labor and Employment Relations Association (LERA) National Policy Forum. I've been invited to speak on a panel entitled, "A New Progressive Era? The Influence of State and Local Initiatives on National Policy." Presumably, I was invited because I wrote a book entitled The New Progressive Era. I don't have much to say about the real topic of the panel, which is whether "recent local and state initiatives on employment and labor relations" will lead to "national level policies." If I'm going to be any help at all, I need to reflect on general parallels between the Progressive Era (1900-1924) and today. This will also be a chance to present a different view of the original progressive movement than the one I held in the 1990s.

Huge changes occurred during the Progressive Era, and the word "progressive" had such positive connotations at the time that proponents of every important development liked to call it "progressive." (Walter Lippmann observed in 1921 that "an American will endure almost any insult except the charge that he is not progressive.")

Among the important changes that could be called "progressive" were: administrative centralization in industry and government; specialization, professionalization, and the cult of science and expertise throughout society; the increased use of formal rules and regulations in both government and business, often to protect consumers; reform legislation designed to reduce the impact of money in politics; the "efficiency movement"; the growth of organized labor (which mimicked forms of administration seen in business and the state); and a new ideal of citizenship. Whereas the 19th century citizen was supposed to be a loyal and enthusiastic member of an identity group, the progressive citizen was supposed to be an independent, informed judge of public policies. That ideal led to concrete reforms such as the secret ballot and attacks on political parties. Overall, politics became less "popular," more a matter of expert administration; and turnout dropped accordingly.

In my book, my heroes were Robert M. La Follette, Sr., Jane Addams, John Dewey, and their associates. Although these three surely deserve the label "progressive" (for instance, La Follette won the Progressive Party nomination), they were ambivalent about the main trends I mentioned above. In the Library of Congress, I read a book manuscript that La Follette wrote--but for some reason never published--criticizing the state government of Wisconsin for becoming overly professionalized, expert-driven, bureaucratic, and distant from ordinary people. Jane Addams battled the Chicago Democratic machine but wrote appreciatively of the emotional connection between a machine Alderman and his constituents. Compared to the "village kindness" of the ward boss, she wrote, "the notions of the civic reformer are negative and impotent .... The reformers give themselves over largely to criticisms of the present state of affairs, to writing and talking of what the future must be; but their goodness is not dramatic; it is not even concrete and human."

I thought that my favorite progressives were characterized by three main principles:

They were democrats, willing to do what the public wanted rather than push policies that they favored for theoretical reasons. That was the heart of Dewey's pragmatism: a rejection of general rules and a commitment to democratic processes. It is what separated all of my heroes from the Socialist Party of the time, which used democratic procedures but which was wedded to Marxist principles. La Follette embodied Deweyan pragmatism even before Dewey wrote any influential books. As a candidate, La Follette typically avoided strong policy proposals but argued for a more democratic process and pledged to do what the people wanted. Most of his policies were procedural--campaign finance, lobby disclosure, and the like. They were egalitarians, critics of political processes that gave some people more power than others because of money, secrecy, or administrative structures. They loved deliberation. La Follette printed the following words by Margaret Woodrow Wilson on the front cover of his popular Weekly in 1914: "No wonder that [politicians] do not always know what the people want. Let us get together so that we may tell them. All of our representatives are organized into deliberative bodies. We, whom they represent, ought also to be organized for deliberation. When this happens, and then only, shall we vote intelligently." For these reformers, democratic participation did not mean developing preferences and expressing them in the ballot box or the marketplace. It rather meant discussion, listening and persuading--collective education.

I would now add a fourth principle:

They understood that deliberation and democracy could not be achieved through changes in rules and processes alone. Citizens needed new skills and identities in order to participate. Culture-change was essential. This explains why they built model institutions with strong democratic cultures, such as Hull-House, the Chicago Lab School, and the University of Wisconsin's Department of Debating and Public Discussion, which sent 80,000 background papers per year to citizen groups.

The people I'm calling Progressives faced several serious dilemmas that we still haven't solved. It was hard to sustain public support for "democracy" without promising concrete social and economic changes. Yet to promise a particular policy, such as a child-labor law, meant circumventing public discussion and dialogue. Progressives appealed to the general or public interest, but people understandably identified with narrower group interests. The Progressives built impressive small institutions that were genuinely deliberative and democratic; but they never figured out how to increase the scale of these efforts. For example, Deweyan educational practices, when implemented on a large scale, became grotesque parodies of his ideas. Finally, despite their ambivalence about expertise and centralization, the Progressives never designed large and strong institutions that remained participatory and egalitarian. The Wisconsin state government that La Follette criticized as bureaucractic and arrogant was the very same government that he had built during his own gubernatorial administration. Although he wasn't directly responsible for how it developed, he did not know how to stop it from becoming a Weberian bureaucracy.

Despite these dilemmas, I believe the Progressives whom I admire contributed an enormous amount to mid-20th-century liberalism. Most progressives (including Dewey) were ambivalent about the New Deal. But the New Deal benefited from the open deliberations of the Progressive Era (which generated a host of creative policy ideas) and from ordinary people's trust in public institutions. People trusted the government and were willing to spend tax money on it because--among other reasons--many teachers, social workers, conservationists, and other public employees had Deweyan traditions of working collaboratively with laypeople. For instance, neighbors of Hull House and its employees had real mutual accountability and respect. So when Hull-House was "taken to scale" in the New Deal, people could feel a place in the new government agencies.

In short, Progressive-Era pragmatism contributed to something that it wasn't--to the ideology of mid-century liberalism that dominated government from the FDR to LBJ. Liberalism was a robust ideology because it had: a comprehensive diagnosis of social problems, a store of moving rhetoric and famous leaders, an impressive array of policies and institutions, and a set of active constituencies, many of which benefited from liberal policies. Thus the ideology replicated itself from generation to generation.

But, in my opinion, mid-century liberalism has been dead for 25 years. The Great Society diagnosis doesn't fit our contemporary problems, many of which have strong cultural dimensions. The leftover institutions, such as public schools and environmental agencies, are insufficiently participatory and accountable. The liberal constituency has shattered, in part because people don't have good reasons to trust the government.

The time is ripe for a revival of La Follette-style pragmatic progressivism. An open-ended, deliberative approach to politics is timely now because we don't have any impressive ideologies. (Conservatism is as dead as liberalism is). An enthusiasm for deliberation is appropriate for an era in which we have exciting new techniques and technologies for public discussion and collaboration. It's time for a new look at government agencies now that businesses and nonprofits are becoming less hierarchical and "flatter." And small-scale experimentation is appropriate given the frailties of our large public institutions. Today's charter schools, watershed restoration projects, community development corporations, and land trusts may well be our equivalents of settlement houses and lab schools.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: revitalizing the left

May 9, 2007

lessons from the health care defeat

At the Democratic presidential debate in South Carolina, the candidates were asked: "What is the most significant political or professional mistake you have made in the past four years? And what, if anything, did you learn from this mistake which makes you a better candidate?" Senator Clinton replied: "Certainly, the mistakes I made around health care were deeply troubling to me and interfered with our ability to get our message out."

I would love to know what mistakes she thinks she made and what she learned from them. I would be sincerely interested in her full response--if she could give it candidly--because she is highly intelligent and experienced and she has a unique perspective as organizer of the 1993 health care reform effort. We cannot know for sure, but I suspect she would disagree with my interpretation, which is the following. ...

The 1993 health reform proposal represented a particular kind of liberalism which is dead. The proposed system would have required an enormous degree of public trust. The details were extremely complicated, so that people (certainly including me) could not understand them. The structure that Clinton proposed would have evolved and shifted as public-sector organizations negotiated with private insurers. Thus the details of the health plan were not only complex; they were unpredictable. Why then should citizens entrust thousands of their dollars per capita to the government? The implicit reasons were: 1) We (in the government) are more trustworthy than those greedy people in HMOs and insurance companies. 2) We will represent you because we are elected. We will act like an interest group in the marketplace, bargaining for advantage; but you will own us. And 3) We are extremely smart. Ira Magaziner is a Rhodes Scholar; we've known him since college days--he has a high IQ.

Those three arguments could work in 1935, when Roosevelt brought lots of talented Ivy Leaguers to Washington to create elaborate programs. It could work in those days because there was more deference to expertise, more hostility to business, and a deeper national emergency--but also because people belonged to institutions with which they had real contracts. They were members of local party organizations and unions that had to pay attention to them in return for their participation. In turn, the New Deal administration was accountable to the unions and the party organizations.

By 1993, that infrastructure was gone. Less than 15 percent of the private sector workforce belonged to unions, which seemed unaccountable even to their shrinking membership. The parties were not organizations at all, but collections of political entrepreneurs. Although we have very pressing reasons to distrust private health insurers, we also have reasons to distrust the government, which gives us urban police departments, the Iraq war, etc.

In the South Carolina debate, Senator Clinton mentioned "getting the message out." I don't think a better message for government-funded health care could work, under these conditions. I'd argue that we cannot have a national health care reform plan unless we use one of these strategies to earn public trust:

1) We could design a government-run system: for example, a single-payer insurance fund that actually set prices for health care. This would give the state enormous power, but also achieve huge savings. In order for people to trust it, they (or a large representative group of them) would have to be actively engaged in writing the law and then revising it. We would need an ambitious series of public deliberations involving a representative sample of citizens. As a charter member of the Deliberative Democracy Consortium and a board member of AmericaSpeaks (which organizes such processes), I'm hopeful that this approach could work. However, I must concede that we have no idea whether public deliberations could build trust for an enormously expensive program, especially if well-funded special interests bitterly attacked it.

2) We could rebuild participatory local institutions as the base for stronger government. That's an attractive idea, but one that would take decades to achieve, if we could figure out how to do it at all.

3) We could have some simple and transparent system that was trustable because it was understandable. I don't think that the government could set prices, because that is inevitably complex. Instead, the government would probably have to issue vouchers that people would use to buy insurance. Unfortunately, we would then be stuck with insurance-company profits and marketing costs.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: revitalizing the left

February 23, 2007

managing risk

In an age of weak family structures and communities--and unstable employment--individuals and nuclear families are on their own; they need to be able to manage risk so that they can bounce back from adversity. To help people to hedge risk is different from guaranteeing their welfare or reducing social inequality. It probably isn't adequate, but it is important in the current era of high volatility.

What are the big economic risks for Americans, especially for the working class? Being laid off or seeing one's salary drop dramatically, perhaps because of a reduction in paid hours. Sickness or injury, including injury caused by crime. Divorce and widowhood. Kids who are sick or in trouble. Business failure, including the failure of very small enterprises such as trading pages on e-Bay. Loss of property (such as homes and vehicles) due to robbery, fire, or accidents. Steep declines in the value of one's home or land, such as we see in Rust Belt cities and the Farm Belt.

There are financial instruments designed for some of these risks--for example, home insurance. But sometimes such instruments are too expensive for people whose property is particularly modest. Other risks do not seem to be covered at all by available insurance (divorce, for instance; or the delinquency of one's child). The government covers some people's medical care, but many are not eligible for Medicare or Medicaid and cannot afford private packages. The state is supposed to prevent crime in the first place and can sometimes order restitution. But crime can devastate its victims.

It's interesting to envision a comprehensive set of mechanisms for managing these risks. Some mechanisms could be provided by the state or state-subsidized. Others might be developed by private organizations.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: revitalizing the left

November 29, 2006

the state of play

Until recently, I would have summarized the partisan debate in the United States as follows.

On domestic policy, the Democratic coalition encompassed many factions, but the dominant one was led by Bill Clinton and Robert Rubin. Their priorities were: balancing the budget (as a means of supporting aggregate economic growth), followed by spending on education, welfare, and health, followed by tax cuts for lower-income families. The public recognized these priorities: Democrats were trusted on fiscal policy, overall economic policy, and health and welfare. Whether or not "Rubinomics" was adequate or desirable, it coincided with prosperity and it matched majority preferences. Once the Democrats settled on it as their dominant position after 1994, they made at least incremental progress in most elections that emphasized economic issues.

In contrast, the Republicans officially stood for tax cuts, followed by spending cuts to balance budgets. But they had decreasing credibility on these issues. In any case, the public did not put tax cuts first.

On social issues, the country had moved far in the direction of libertarianism, so that the live issues of the day (such as gay marriage) would have seemed very radical a generation before. However, on those live issues, the Republican position was more popular than the Democratic one. Hence, in elections that emphasized "values," Republicans usually prevailed.

On foreign policy, the Republicans stood for putting America first. They appeared more willing to use military force, but only in America's economic or security interests. This was a clear position--not one that I favor, but one that had pretty strong popular support. In contrast, the Democrats seemed highly conflicted, unable to resolve debates left over from the Vietnam era that pitted elements of isolationism, nationalism, human-rights idealism, pacifism, and Realpolitik. The public did not know where the Party stood, and that hurt Democrats when foreign affairs rose on the national agenda after 9/11. Kerry�s statement that he had voted for the war before voting against it epitomized the Democrats� reputation on foreign policy. To be fair, many individual Democrats held consistent positions, but the Party had not worked out its debates, which is partly why Kerry emerged as the nominee.

The last two years have changed much of this. Republicans are now associated with foolish unilateral adventurism and a careless disregard for American national interests. Internal debates have erupted on their side. That is clearly one reason that the Democrats won the 2006 election. But they still lack a coherent philosophy in foreign affairs.

We could now enter a creative period in which new alternatives are developed, some enjoying bipartisan or "strange-bedfellow" support. Serious alternatives would combine broad philosophical positions with specific policy proposals.

However, we could also enter a period in which Democrats expect to coast while Republicans continue to suffer (deservedly) from the Iraq debacle. That period would last two years at the most, by which time the Republicans would find new leadership and the Democrats would be expected to hold persuasive positions on foreign affairs. Thus the Party should begin a robust and divisive internal debate right now, so that a winning faction may prevail before 2008.

permanent link | comments (1) | category: revitalizing the left

November 13, 2006

an analogy

| The Sixties | The 2000s |

|---|---|

| 1960 election: Reflects unusually high degree of ideological consensus. The main issue is the personality of the incumbent VP versus "change." | 2000 election: Reflects unusually high degree of ideological consensus. The main issue is the personality of the incumbent VP versus "change." |

| Series of national traumas: Assassinations of JFK, MLK, RFK, race riots, Kent State | Series of national traumas: 9/11, anthrax, Katrina |

| Escalating war in Southeast Asia | Escalating war in Southwest Asia |

| Left mounts strong challenge to the ideological status quo (with a basis in cultural/personal issues) | Right mounts strong challenge to the ideological status quo (with a basis in cultural/personal issues) |

| Ideological backlash: Nixon elected | Ideological backlash: Democrats take Congress |

| Residue: cultural change in a libertarian direction, lingering resentment on the right, generally more conservative economic policies | Residue: ??? |

permanent link | comments (4) | category: revitalizing the left

November 6, 2006

what to do with a majority

There is a raging debate about how the Democrats should use a House majority, if they win one on Tuesday. On the left, some are framing the question as whether the Democrats will have the "courage" to tackle the Bush administration by conducting high-profile, aggressive investigations. (See comments here, or Paul Krugman.) In my view, it would take no "courage" at all to yield the House agenda to Henry Waxman and his investigations of procurement scandals and the like. "Courage" would mean passing a just budget or a bill to reduce Americans' consumption of coal and oil. But that would require focus, discipline, time in committees and on the floor of Congress, public attention and support, and partnerships with key congressional Republicans. If Democrats try to drive all the public attention to scandals, they will have no chance of pushing really significant legislation through the House.

Regardless of what happens on Tuesday, conservatives can be basically satisfied with the fundamentals of American politics. Politicians of both parties are embarrassed to mention raising taxes, even if the alternative is to borrow money from the next generation. None of them seriously wants to cut the incarceration rate or end the �war on drugs.� They are almost all afraid to criticize the military brass for anything it might do.

If I were a conservative, I would be hoping that a Democratic Congress would concentrate on the malfeasance of the Bush administration. In the worst case (from my imaginary conservative perspective), the Dems would uncover some really bad behavior that Americans don�t already know about. Fine--in that case I would join the Democrats in outrage against Bush and back a new set of Republican leaders in �08. All the fundamentals would still be in place.

In the best case (again from a conservative perspective), the Democrats would find nothing startlingly new, would waste two years, and would reinforce a reputation for lacking vision and competence.

My biggest fear, if I were a conservative, would be that the Democrats would largely ignore Bush and pass a series of smart, aggressive, progressive bills to help working families, ameliorate the sitation in the Middle East, strengthen education, and tackle oil dependence. Then my guys would have to filibuster or veto good bills, or else allow them to pass and thereby move the country somewhat leftward. By �08, Democrats would have a reputation for vision and competence and my side would be in real trouble.

I'll bet that the Democrats will not allow investigations to dominate their agenda or the news coverage, because they understand the need to look competent and forward-looking. They know that Bush is already history. However, I'll also bet (sadly) that they will fail to pass courageous, progressive legislation, precisely because public opinion is still basically conservative on fiscal questions, and liberals haven't figured out how to change that.

(See Rich Harwood's "Election Day hubris" for a related point.)

permanent link | comments (1) | category: revitalizing the left

August 29, 2006

new thoughts on canvassing

Dana Fisher's book, Activism, Inc.: How the Outsourcing of Grassroots Campaigns Is Strangling Progressive Politics in America, is about to appear with a blurb from me on the back cover:

For idealistic young progressives today, there is basically only one paid entry-level job left in politics: canvassing. Dana R. Fisher is the first to study this crucial formative experience. Essentially, she finds that the canvass is an alienating and undemocratic experience. As a result, we are squandering the energy and ideas of a whole generation. What's more, a progressive movement that relies on regimented canvassing is doomed to defeat because it lacks an authentic connection with citizens. Unless we take seriously the rigorous evidence and acute arguments of Activism, Inc., the future looks grim.

My conscience is bothering me for two reasons. First, my summary of Fisher's book is a pretty strong statement, perhaps exaggerating what she says. Second, she does tell a highly critical story (as her subtitle indicates). My blurb lends my authority to her criticism, suggesting that her "rigorous" and "acute" scholarship must be true. In fact, given what little I know directly about canvassing, plus the evidence that Fisher presents in her book, I cannot say whether her account is accurate or not.

Fisher makes three main points:

1) Canvassing is bad for canvassers: many are burnt out, stuck in dead-end positions, or alienated because they have to raise money by reciting �scripts� that they do not fully understand.

2) Canvassing for progressive causes is being centralized into a few big, multi-purpose operations. This consolidation reduces the connection between the canvassers and the various lobbies for which they raise money.

3) Canvassing is bad for democracy, because professional activists set the progressive political agenda and lobby using money from people whom they have mobilized through one-way conversations. Democracy needs organizations in which citizens frame their own agendas through conversations, develop working relationships with peers and neighbors, and then hold professional lobbyists and leaders accountable. (This third point is mentioned but not developed in the book; it's partly my own extrapolation.)

The first point--that canvassing is bad for canvassers--is based on Fisher�s 115 interviews. She provides many quotes, which actually tell a mixed story. Some of the interviewees have positive things to say; some are critical of the canvass. She does not code the interviews so that she can provide statistical summaries (such as "55% were negative"), but she does use words like "most."

I don't think the lack of statistics matters. Selecting and coding interviews is a fairly subjective process, so any hard numbers would look more precise than they would actually be. In essence, we must rely on Fisher to generalize fairly and accurately from her own observations. The fact that she quotes people who have a positive view of canvassing could be taken as evidence that she is scrupulous and balanced. Or the fact that she draws very negative conclusions, despite having talked to people whose views were positive, could be taken as a sign that she exaggerates.