March 22, 2010

the press turns to explanation, after the decision is made

"American consumers, who spent a year watching Congress scratch and claw over sweeping health care legislation, can now try to figure out what the overhaul would mean for them." -- Tara Siegel Bernard, today's New York Times.

Actually, the news media spent a year feeding American citizens a steady diet of stories about Congressional procedure, the possible impact of health-care reform on elections, and quotes that falsely described the bill or denounced its critics. Americans never showed any desire to watch Congress "scratch and claw." They would have appreciated some information about what various legislative bills would do.

Now that the bill has passed, reporters finally feel an obligation to explain it. Bernard's story lists the major provisions, although The Times also feels obliged to run a front-page "news analysis" of Obama's alleged strategy (he cast a "bet that the Republicans ... overplayed their hand"), a separate article about political fights to come, and a panoply of one-liners: "Freedom dies a little bit today ..." "It is almost like the Salem Witch trials ..." The ratio of substance to horse-race reporting remains low, but I predict that weekly news magazines and metropolitan dailies will begin to run helpful explanatory pieces.

The job of the press is not to tell us who won or lost, or how a bill will affect our votes in the next election. Its job is to give us information that we can combine with our values to reach judgments. Measured by that standard, the press failed spectacularly during the health care debate. Reporters are partly responsible for the public's deep misunderstanding of the bill--although the Democratic leadership also did a poor job explaining it, and we citizens should bear some responsibility, too.

Brendan Nyhan, a political scientist/blogger who studies such things, doubts that public misconceptions will dissipate any time soon. His research suggests that myths are stubborn and that efforts to correct them often backfire by inadvertently reinforcing the very misinformation that they seek to rebut.

As it must be, his work is based on data from the past, plus lab experiments. I think the health care situation may prove unusual, because (1) the legislation is momentous and will capture public attention, (2) the level of misinformation is striking, so there is lots of room for improvement, (3) people have incentives to learn what the bill means to them, (4) unless you are an ideologue, you have no motivation to reject positive information about the bill, and (5) trustworthy intermediaries, such as primary care physicians, have incentives to understand it and explain it accurately. I would be surprised if public understanding doesn't rise.

But there I go, prognosticating about public opinion--just like a reporter. The important question is what the bill will actually do. I encourage everyone to take a few minutes to find out, if you don't know already.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: press criticism

November 11, 2008

my favorite article on the 2008 campaign

That would be Mark Danner's "Obama & Sweet Potato Pie" in the New York Review of Books. Danner describes two rallies, one for Obama and one for McCain. As he notes, the national press corps follows the candidates, listens to them repeat their stump speeches time after time, and reports only the new lines that are inserted daily for their interest--usually attacks on the other candidates or responses to attacks. I well remember seeing Bill Bradley speak live in the 1992 campaign and marveling that the only aspect of his speech that appeared in the newspaper the next day was a line about Bill Clinton. The whole thing is a game that the campaigns and the press know how to play.

But a campaign also consists of whole speeches delivered in real settings to people from geographical communities. Danner depicts two such occasions as the dynamic interplay between the candidates and their audiences. He does an unusually good job of portraying both sets of voters with understanding and sympathy. He suppresses his own judgments in the interest of clear-eyed reporting. For me, the piece pretty much sums up the whole campaign.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: press criticism

October 30, 2008

media bias and election outcomes

The conservative world is abuzz with the idea that liberal news media are either hurting McCain or making his polling results look worse than his real support in the public. I know plenty of liberals who believe that the rise of Rush Limbaugh and Fox News accounts for conservative electoral victories after 1992. These two claims don't cancel out; one or both could be true. But a full statistical model of election outcomes would have to factor in at least:

a. The fit between candidates' positions and public opinion

b. The candidates as communicators/symbols

c. Strategic and tactical political decisions by campaigns

d. Grassroots activity by citizens

e. Campaign finance

f. Changes in the real economic and social circumstances of voters before the election

g. The real performance of the incumbent administration

h. Media bias

I can imagine that (h) would account for some of the variance in election results. But I don't think it can explain too much, because there is a lot of evidence about the importance of (f). Specifically, changes in inflation-adjusted, disposable household income before an election remarkably predict whether the "in" or "out" party wins. And people know their own income; they don't need the media to tell them.

We should wish that (a), (d), and (g) would explain most of the variance in election results. Those are the democratic inputs. Political reforms should maximize the importance of these factors. (H) is unfortunate, but I doubt it's very important once the other factors are considered.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: press criticism

March 20, 2008

part of the problem

I generally don't like to quote at length from prominent blogs, but I can't improve on this reaction by Jay Rosen:

I was watching CNN for Obama's speech. Moments after it concluded Wolf Blitzer was asked to tell us what he heard in it. Wolf's ear is the big ear for the Best Political Team on Television, according to CNN. So he went first. And according to Blitzer, Obama's speech boils down to a "pre-emptive strike" against various attacks on the way: videos, ads, and news controversies that are sure to keep Reverend Jeremiah Wright and "race" in play as issues in the campaign. (I don't have his exact words; if someone out there does, ping me.)Wasn't the speech about that very pattern?

This is the style of analysis--and the level of thought--we have become miserably utterly used to, especially from Blitzer, but also many others on TV: everything is a move in the game of getting elected, and it's our job in political television to explain to you, the slightly clueless viewer at home, what the special tactics in this case are, then to estimate whether they will work.

That Blitzer, offered the first word on that speech, did the savvier-than-thou, horse race thing tells you about his priorities (mistakenly "static," as Obama said about Wright) and his imaginative range as an interpreter of politics (pretty close to zero.)

Compare Wolf to active, thoughtful citizens who care:

"The Rev. Joel Hunter, senior pastor of a mostly white evangelical church of about 12,000 in Central Florida ... said the Obama speech led to a series of conversations Wednesday morning with his staff members. "We want for there to be healing and reconciliation, but unless it’s raised in a very public manner, it’s tough for us in our regular conversation to raise it."Julie Fanselow: "Time and again Tuesday, speakers at Take Back America and writers on blogs like The Super Spade and Booker Rising and Pam's House Blend echoed and dissected and even wept over what Obama had said in Philadelphia."

Rich Harwood reflects on what we should do when someone (such as Rev. Wright) "cross[es] the line of politeness and rupture[s] norms of give-and-take." We should, says Rich, "step forward and renounce them in ways that reflect the kind of public life and politics we seek to create. Let us take in the fullness of their argument and respond in kind - with clarity, forthrightness, and strength of conviction, even love. I do not suggest that anyone should back down, but neither do I advocate a slash and burn response that poisons the very public square we wish to invigorate."

Less favorable to Obama, but equally responsible and deliberative, is Bill Galston's take.

permanent link | comments (1) | category: press criticism

February 20, 2008

an opening for the news media

David Carr, a financial reporter for the New York Times, argues that the rising youth turnout rate offers the news media an opportunity to expand their audience among young people. He quotes me, saying, "I think that there is a clear message in here for the media: these campaigns have made very direct and serious pitches to young people and they have responded. ... I think it demonstrates that if you approach them in a specific way about things they care about, they will engage."

This is certainly an important issue, because using the media (especially a daily newspaper) correlates powerfully with voting and all forms of civic participation, including membership in groups. For young people, news consumption has fallen:

This graph provides an incomplete picture. It doesn't continue until 2004-7, when you would see some increase in newspaper readership. And it omits other news sources, such as the Internet. But notice that the decline was long, slow, and steady and started well before the Internet achieved mass scale.

I serve as a trustee of the Newspaper Association Foundation and do other work in this field because I believe that the news media (as well as schools and other institutions) need to invest more in building young people's interest in the news. They are also going to have to rebuild trust, because American youth are more cynical--or sophisticated--about bias and spin in the press than they used to be. The graph below shows trends in trust; our qualitative research finds that young people are especially sensitive to perceived bias and manipulation.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: press criticism

November 21, 2007

interacting with "the media"

(We're heading west for Thanksgiving, and this will be my last post until Monday.)

I have minuscule impact on the news media, but I do have interesting experiences with journalists.

For example, yesterday at 7 am, I walked the halls of XM Radio in Northeast Washington, DC. XM Radio produces 170 separate channels of audio programming, mostly for specialized audiences. I was on my way to be interviewed for "POTUS '08," a channel that talks about nothing but the presidential campaign, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. I should note that the questions turned out to be very good; they went far beyond the usual horse-race analysis. But what struck me were all the studios for the other radio channels, visible through glass windows along the groovy curving halls as I walked to my interview. Baseball jerseys and bats covered the walls of one studio, where three guys were talking into mikes. Another studio looked like a business suite with leather furniture and copies of the Wall Street Journal. It all seemed like a Monte Python skit. I expected to see the "Yo-Yo Channel" around the next corner, with people in beanies keeping their Imperials in motion, 24/7.

Later in the same day, a crew came to interview me for a documentary about the future of democracy (not about my book of that name; about the actual future of our actual democracy). The crew is also filming the interview process to create a video blog about making the documentary. That explained why there were two cameras, one filming the other one. Again, I should note that the interview questions were very thoughtful.

Finally, not long ago, a foreign TV crew came to interview me about KidsVoting USA. This is a fine program that involves discussing a campaign in school and then conducting a mock election. A rigorous study has found that participants' parents actually vote at higher rates, because the program stimulates discussion of politics around the dinner table. The TV crew had gone to Duluth, Minnesota (i.e., the heartland) to film a KidsVoting class and some dinner-table conversations. After the interview, the reporter told me privately that she was so moved by what she saw in Duluth that she was thinking of quitting her job to start KidsVoting in her home country. She wanted my advice about fundraising.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: press criticism

September 4, 2007

7 questions about the campaign

On the front page of Saturday's Washington Post, in a "Campaign Memo" addressed "To: The Voters" about "The Seven Things You Need to Know about the 2008 Race," Dan Balz addressed the following questions:

1. Is the Clinton campaign a true juggernaut -- or is that just what she wants everyone to believe?

2. Is there a Republican front-runner?

3. Is anyone on either side positioned to break into the top tier?

4. Does the new, turbo-charged calendar make Iowa and New Hampshire more important -- or less?

5. Is it too late for Al Gore or Newt Gingrich to get into the race?

6. Do ideas matter in this election?

7. When do I really need to start paying attention, and should I trust the polls?

These are questions for spectators who are considering following the 2008 campaign as they might follow the NFL season--as a contest among professional teams. The big underlying question is: Who's going to win? But what if you follow the campaign as a citizen concerned about the country and the world? Then your questions would be quite different:

1. What are our problems as a country?

2. What are some leading diagnoses and interpretations of these problems?

3. What should we do about our problems?

4. What role do I have?

5. What role does the next president of the United States have?

6. What are the candidates saying about how they would play their roles if elected?

7. What does other evidence (such as the candidates' records, behavior on the campaign trail, choice of advisers, and core constituencies) tell us about how they would play their roles?

Perhaps Dan Balz would say that he cannot address my questions without editorializing. But he can hardly claim that he merely provides "the facts," since his memo is full of declarative judgments about the horse race. (In his magisterial opinion, it is too late for Gore and Gingrich. No candidate has proposed any significant big ideas yet. Etc.) Besides, I'm not asking the Post to tell us what our problems are and how to solve them. I'm asking them to give us the factual basis to help us make up our own minds--along with a sampling of interesting views quoted from a variety of experts and activists.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: press criticism

April 19, 2007

too much coverage of the Virginia Tech tragedy

The amount of coverage has been staggering--dozens of stories per day in the top national newspapers, nightly broadcast news programs that are lengthened by half an hour, 24-hour repetitions of the same information on cable news, even a blow-by-blow account in the "Kid's Post" section of the Washington Post, which my 7-year-old reads. I first found out about the Blacksburg tragedy because a student TV news crew stopped me on the street to ask my opinion. This is a global phenomenon: Le Monde and the BBC also led with Cho Seung-hui's picture when I looked.

It's a choice to devote so much space and time to those 33 deaths. Bombers killed 158 in US-occupied Baghdad on Wednesday. Nigeria, the biggest country in Africa, saw violence connected to its presidential vote. Comparisons are odious; they imply that one doesn't care about particular victims and that human lives can be counted and weighed. I do sympathize with the Blacksburg victims and their families. I sympathize because I have been told their stories in detail; but there are many other stories that I could have been told--other tragedies, or (for that matter) other narratives that are important but not tragic.

Perhaps the Virginia Tech victims deserve sympathy from all of us, but I suspect they would prefer less attention. I find it hard to see how the deserve something they don't want.

One reason to tell the Virginia Tech story in detail is to provide us with the information we might need to act as voters and members of various communities. For instance, I work at a university much like Virginia Tech and could agitate for new policies in my institution. But it is generally a bad idea to act on the basis of extremely rare events. There have been about 40 mass shootings in the USA. During the period when those crimes have occurred, something like half a billion total people have been alive in America. That means that 0.000008 percent of the population commits mass shootings. There cannot be a general circumstance that explains why someone does something so rare. The availability of weapons, mental illness, video games--none of these prevalent factors can "explain" something that in 99.999992 percent of cases does not happen. (Bayes' theorem seems relevant here, but I cannot precisely say why.)

It is foolish to use such rare events to make policy at any level--from federal laws to school rules. For instance, if lots of people carried concealed weapons, there is some chance that the next mass killer would be stopped after he had shot some of his victims. But millions of people would have to carry guns, and that would cause all kinds of other consequences. The day after the Blacksburg killings, two highly trained Secret Service officers were injured on the White House grounds because one of them accidentally discharged his gun. Imagine how many times such accidents would happen per year if most ordinary college students packed weapons in order to prevent the next Blacksburg.

The last paragraph was a rebuttal to those who want to use Cho Seung-hui as an argument for carrying concealed weapons. But it would be equally mistaken to favor gun control because it might prevent mass shootings. Maybe gun control is a good idea, but not because it would somewhat lower the probability of staggeringly rare events. Its other consequences (both positive and negative) are much more significant.

If obsessive coverage of a particular tragedy does not help us to govern ourselves or make wise policies, it does reduce our sense of security and trust. It reinforces our belief that "current events" and "public affairs" are mostly about senseless acts of violence. It plants the idea that one can become spectacularly famous by killing other people. These are not positive consequences.

It is moving that some students have started a "reach out to a loner" campaign on the Internet. They are trying to respond constructively to something that they have been told is highly important. Imagine what they might accomplish if they turned their attention to the prison population, the high-school dropout problem, or even ordinary mental illness.

permanent link | comments (2) | category: press criticism

April 17, 2007

whom does a White House reporter represent?

Another person who spoke on Saturday at Penn State was David E. Sanger, the chief White House correspondent of the New York Times. After his speech, I asked him whom he thought he represented when he rode on Air Force One or sat in the White House briefing room. He replied, "You always represent your readers." I asked him who he wished his readers were. I was wondering, for instance, whether he would like to reach (and therefore "represent") a cross-section of the whole national population, if that were possible. He replied that Times readers are always going to be unusual in some respects. They have a high median level of education and tend to have especially enjoyed their own college experiences. He argued that skew was acceptable as long as everyone can get access to the Times, which is easy now via the website.

That's a plausible answer. It's better than claiming that the Times only serves the truth. Despite its slogan ("All the News that's Fit to Print"), the newspaper obviously makes choices about what stories to cover and whom to interview, based on value-judgments about what is most important. Sanger had conceded that point in earlier comments.

I can imagine a reporter saying that he represents no one, or only his employer. But that would raise questions about why he should have access to the president of the United States. I can also imagine a New York Times reporter saying that she represents "the American people." That's consistent with the Times' image as an objective source of information for any citizen (regardless of creed, region, or party) who wants to make independent decisions. I've previously quoted Adolph Ochs, who said, when he bought the Times in 1896, that he intended to "give the news, all the news, in concise and attractive form, in language that is parliamentary in good society, and give it early, if not earlier, than it can be learned through any other reliable medium; to give the news impartially, without fear or favor, regardless of any party, sect, or interest involved; to make of the columns of The New York Times a forum for the consideration of all questions of public importance, and to that end to invite intelligent discussion from all shades of opinion." That's a high ideal, and it reflects a kind of implicit contract between the whole public and the Times' reporters. That contract has come into question with recent scandals, but I don't think that tighter ethical rules would fully resolve the problem. The Times cannot represent the whole American people if the 1.1 million people who buy it are skewed by class, ideology, and region. It could struggle to make its readership nationally representative, but that would probably require a change of tone, topics, and perspective. Perhaps it is best to say, as Sanger did, that he simply represents his readers and welcomes anyone to join their company.

permanent link | comments (2) | category: press criticism

July 12, 2006

box score political reporting

One of the standard clichés of journalism is the treatment of political news as if it were a sport. Each event is described as a victory or a defeat for a particular politician. For instance, here's how the two papers that I read over breakfast this morning reported the latest Administration policy on prisoners:

The New York Times: The new policy "reverses a position the White House had held since shortly after the Sept. 11 attacks, and it represents a victory for those within the administration who argued that the United States' refusal to extend Geneva protections to Qaeda prisoners was harming the country's standing abroad."

The Washington Post: "The developments underscored how the administration has been forced to retreat from its long-standing position."

The Administration's change of position was a defeat: that's a fact. And it's undeniable (almost tautological) that the shift was a "victory" for those who opposed the status quo. But reporters could choose many other facts to provide: for example, information about what has been done to various prisoners. The reliance on political wins and losses has the following serious drawbacks:

1) It encourages laziness. You don't have to do any actual reporting to figure out that an event is good or bad for a politician.

2) It reinforces the notion that politics is a spectator sport, in which the important question is "Who's winning?" (not, "What's happening?").

3) It adds to the political cost that incumbents incur when they change course for good reasons. When George Bush found out that Abu Zubaydah, whom he had described as Al-Qaeda's chief of operations, was mentally ill and of no consequence, he supposedly told CIA Director George Tenet, "I said he was important. You're not going to let me lose face on this, are you?" If that's true, it's evidence of almost criminal irresponsibility. But Bush also knew that if he changed his position, the press would report that as a sign of weakness--a "setback" or "defeat"--instead of allowing the president to take credit for learning. Reporting politics as a box-score only increases the odds that leaders will act like Bush.

(In fairness, I should note that after I read this morning's papers and decided to write this post, I looked around for other examples of box-score journalism on the prisoner issue. The AP, Reuters, and L.A. Times stories really did not use that frame.)

permanent link | comments (0) | category: press criticism

July 10, 2006

the press and civic engagement

Below the fold, I have pasted a longish draft essay on the evolution of the news media and its impact on democracy. (A revised version will go into a book on civic engagement that is due next month.) In essence, I argue that we had a particular model of the news business between 1900 and 2000 that became increasingly dysfunctional for citizens. It offered limited opportunities to write the news--that's a well-known flaw. It also assumed an audience of people who were interested in public issues and who trusted professional reporters to be objective, balanced, reliable, and independent. That audience encompassed the most active citizens, as surveys show. But it shrank rapidly in the last quarter of the 1900s. Resurrecting the twentieth-century press now seems impossible, but the new digital media have promise.

Until the Progressive Era (ca. 1900-1914), most American newspapers and magazines reflected the positions of a party, church, or association and aimed to persuade readers or motivate the persuaded. The exceptions, beginning with the New York Sun in 1833, were independent businesses that sought mass audiences in big cities. All 19th-century newspapers freely combined opinion and news. They printed fiction and poetry along with factual reporting. They often ran whole speeches by favored politicians or clergymen. Standards of evidence were generally low. However, publications were relatively cheap to launch, so they proliferated; 2,226 daily newspapers were in business in 1899.[1] A small voluntary association or independent entrepreneur could break into the news business, hoping to make money or to push a particular ideology, or both.

The nineteenth century was also an age of partisan citizenship, in which people were expected to show loyalty to a party, a union, a church, a town or state, and sometimes a race or ethnic group. Often such loyalties were ascribed from birth; they were matters of affiliation rather than assent, as Michael Schudson writes.[2] Voting was a public act, an expression of loyalty, not a private choice. Politics involved torchlight parades and popular songs; the essence of civic life was boosterism; and newspapers were written in a similarly rousing, communitarian spirit.

As Schudson has shown, the new model citizen of the Progressive Era--an independent, well-informed, judicious decision-maker--needed a different kind of newspaper, one that provided reliable information clearly distinguished from opinion, exhortation, and fiction. Leading newspapers were separated from parties and religious denominations and began to claim objectivity and independence. Their intended audience became all good citizens, not just members of particular groups. When they introduced opinion columns and letters pages, they often strove for ideological balance. As Adolph Ochs announced when he bought The New York Times in 1896, his intention was to “give the news, all the news, in concise and attractive form, in language that is parliamentary in good society, and give it early, if not earlier, than it can be learned through any other reliable medium; to give the news impartially, without fear or favor, regardless of any party, sect, or interest involved; to make of the columns of The New York Times a forum for the consideration of all questions of public importance, and to that end to invite intelligent discussion from all shades of opinion.”[3]

The transformation of the American press coincided with the ascendance of logical positivism, which sharply distinguished verifiable facts from subjective opinions.[4] Furthermore, the independent newspaper arose along with the modern research university, whose mission was to create independent, judicious decision-makers instead of loyal members of a community. Finally, the new press reflected an ideal of a trained, professional journalist that took shape when many other occupations were also striving to professionalize.[5]

At about the time when journalists developed ideals of objectivity, independence, and neutrality, the news business consolidated. For example, the number of daily newspapers in New York City fell from 20 in the late 1800s to eight in 1940. Meanwhile, the first newspaper chains were established.[6] Most people began to obtain news from a daily publication with a mass circulation, and they had relatively little choice. Consolidation of the news business and journalistic professionalism could be justified together with one theory. An excellent newspaper--and later, an excellent evening news show on television--was supposed to provide all the objective facts that a citizen needed in order to make up his or her own mind. The citizen did not need much choice among sources, because any truly professional and independent news organ would provide the same array of facts. Some competition might be valuable to encourage efficiency and rigor, but all credible journals would compete for the same stories. Choice was a private matter to be exercised after one had read the newspaper or watched TV. One was to be guided not by an ascribed identity but by making informed selections among policy options.

This new model had idealistic defenders, but it also had several serious drawbacks that became increasingly clear as the century progressed. First, the new journalism was probably not as effective at mobilizing citizens as the old partisan press had been. Although we lack data on individuals’ newspaper use and civic engagement from before the 1950s, we know that overall turnout and other measures of participation fell as the press consolidated and aimed at professionalism. It seems likely that the new journalism was less motivating.

Second, it became harder to break into the news business once newspapers needed not only printing presses, ink, and paper, but also credentialed journalists, editors and fact-checkers, and a staff large enough to provide comprehensive coverage (“all the news that’s fit to print”). Thus the telling of news became the province of a few professionals employed by large businesses, not an activity open to many citizens. That problem worsened once radio and television arrived.

Third, journalistic professionalism often seemed to introduce its own biases. For example, journalists were trained not to editorialize in news stories. That meant that they often simply quoted other people’s controversial views, usually aiming for as much balance as possible between voices on either side of a debate. To call the president a liar is to editorialize; to quote someone who holds that view is to report a fact. But one still has to choose whom to quote, and the tendency is to interview famous, powerful, or credentialed sources--often those with talents or budgets for public relations and axes to grind. In 1999, 78 percent of respondents to a national survey agreed: “powerful people can get stories into the paper--or keep them out.”[7] Sometimes the norm of “balance” created a bias in favor of the mainstream left and mainstream right, marginalizing other views. On occasion, it meant that reporters gave excessive space to demonstrably false opinions, because they saw their job as reporting what prominent people said, not what was right.

While professional reporters felt bound not to promote policy positions, those who closely covered campaigns and administrations believed they could say who was winning and losing and why politicians had adopted their current positions. Similarities between candidates’ views and public opinion (as measured by the newspaper’s own polls) were taken as evidence that politicians were simply trying to attract votes. Thus readers were offered a relentlessly cynical view of politicians’ motives, plus an interminable policy debate among experts who were equally balanced between the right and left, plus polls showing that one side or the other was bound to win. It is no wonder that many lost interest in politics. None of this coverage helped citizens to play a role of their own.

Modern professional journalism placed a tremendous emphasis on politics as a “horse race.” Three quarters of broadcast news stories during the 2000 campaign were devoted to tactics and polls; only one quarter, to issues.[8] As CNN political director Mark Hannon explained in 1996, his network conducted daily polls because they “happen to be the most authoritative way to answer the most basic question about the election, which is who is going to win.”[9] In fact, during a campaign, the most basic question for a citizen is not who will win, but which candidate to support. But reporters reflexively see that question as one for the editorial pages, whereas they can cover polls as simple empirical facts. Yet the depiction of politics as a horse race suggests that a campaign is a spectator sport (and not a particularly elegant or entertaining one). Controlled experiments have found that such coverage raises cynicism and lowers engagement.[10]

Finally, the ideal news organ of the Progressive Era demanded a lot of trust from its readers. Perhaps objectivity, independence, and balance are possible in theory; in practice, however, any news source is a fallible human product. Major newspapers, magazines, and broadcast news have powerful effects on politics and public opinion. The newspaper that claims to be objective, independent, and nonpartisan asks us to believe that the consequences of its reporting are involuntary, caused by the facts and not by any political agenda. That defense can be hard to swallow. In 2004, two thirds of all Americans thought they detected at least a “fair amount” of bias.[11]

The most glorious chapter in the history of the modern American press was written between 1965 and 1975, when The Washington Post and The New York Times published the Pentagon Papers, broke the Watergate scandal, and had their constitutional role as independent watchdogs upheld by the Supreme Court. Their reporting certainly had consequences, helping to end a war and bring down a president. That was all very well if one opposed the Vietnam War and President Nixon. But the same power could also be used against President Clinton or against the welfare state. Anyone whose political goals were frustrated by the press might find it difficult to trust reporters as objective and independent. One’s skepticism might be reinforced by the fact that each newspaper has owners, investors, and advertisers with economic interests. Writers and editors, too, form a definable interest group.

The debate about corporate power in the news media is at least a century old and is perennially important. In the 1990s, a new discussion began that concerned reporters’ professional norms. Some reporters, editors, and academics argued that the newsroom ideals developed during the Progressive Era no longer served democracy and civic engagement. A newspaper like The New York Times, as Ochs had envisioned it, presumed a public that was interested in current events and ready to act on the information it read. But that public was shrinking, and it could be argued that the prevailing style of news reporting was actually making it smaller by increasing cynicism. Adversarial, “watchdog” journalists still played an important role in periodically uncovering scandals, but it was not clear why an individual citizen should spend money and time reading such information every day. When a big scandal broke, the opposition party or law enforcement was supposed to address it. Why should individuals pay for independent oversight as a public good? Only those who were already civically engaged would choose to subscribe to the watchdog press. Their numbers were falling, and they could find ever less information in the newspaper that could inform for their own civic activities.

In the 1990s, under the labels of “public journalism” or “civic journalism,” news organs experimented with new forms of reporting that might better serve active citizens and enhance civic engagement. For example, instead of reporting the 1992 North Carolina Senate campaign as a horse race (with frequent polls and numerous articles about the candidates’ strategies), the Charlotte Observer convened a representative group of citizens to deliberate about issues of their choice and to write questions for the major contenders. The newspaper offered to publish the questions and responses verbatim. Meanwhile, its beat reporters were assigned to provide factual reporting on each of the topics that the citizens chose to explore. When Senator Jesse Helms refused to complete the questionnaire that the citizens had written, the Observer published blank spaces under his name.[12]

Careful evaluations have found positive effects from this and other such experiments. But public journalism faltered as a movement by the end of the decade.[13] One of the reasons was the sudden rise of the Internet. The newspaper business, panicked by independent websites and bloggers, lost interest in civic experimentation. Meanwhile, many of proponents of public journalism began to see the Internet as more promising than reforms within conventional newsrooms.

After all, blogs, podcasts, and other digital media make possible a return to the press that existed before the Progressive Era--for better and, for worse. The barriers to publication have fallen, not only because websites are cheaper than printing presses, but also because a mass audience has returned to products created by individuals and amateurs. Blogs are endlessly various. Some are specialized sites devoted to careful, factual reporting on particular topics, but most are motivational, ideological, and opinionated, with comparatively low standards of evidence and no trained reporters, fact-checkers, or editors. However, there are millions of them and they often check one another’s facts. Young people are heavily represented and have better opportunities to enter the fray than at any time since 1900.

Twentieth century news media claimed to separate fact from fiction--not always successfully. Then the audience for straight news reporting shrank, along with the rate of civic engagement. But fiction can promote civic participation, as long as it is of high quality. For example, it appears that watching and discussing the fictional world of The West Wing (an NBC television drama) has positive civic effects, whereas watching sitcoms is bad for civic engagement.[14] Unfortunately, the balance of material that major entertainment businesses provide is not good for democracy. But barriers to making films have fallen: artists and other citizens have growing opportunities to create and promote work in all genres that helps people to engage.

Blogs, short videos and audios, and other innovative news media should help to many people to mobilize and organize their fellow citizens. Until recently, trust in journalists, consumption of newspapers, and civic engagement were strongly correlated, but the links may be weakened if people can gain the information they need to participate from other sources. Those who are not inclined to trust the mainstream press will still be able to participate.

Clearly, there are also dangers. An online audience can screen out uncomfortable ideas, thereby splitting into ideologically homogeneous “echo chambers.” There is a relative scarcity of online content devoted to local communities. It can be difficult to distinguish the source and reliability of online information. And the web provides a sometimes confusing mix of fact, opinion, error, deliberate falsification, and overt fiction.

Each of these dangers can be addressed by citizens working online, and sometimes software can help. For example, Wikipedia provides surprisingly reliable information through a system of peer review involving many thousands of volunteers. Technorati’s software increases the chance that bloggers will engage in conversations with their critics, by alerting them whenever their writing has been linked from elsewhere. Social networking software like MySpace (which is currently very popular among the young) can be tweaked so that it helps people identify neighbors with similar political interests.

If there is hope that citizens can address the drawbacks of the new online media through voluntary action, then it would be unwise to enact policies to shape what should be a free space. We should, however, act to prevent two pressing problems. First, it is possible to make handsome profits by limiting customers’ access to material produced by ordinary citizens and driving them to corporate content. Internet service providers may be tempted to provide quicker access to websites that pay them for that advantage; cable companies may charge higher fees for uploading data than for downloading corporate material; and most search engines already sell preferential treatment. Legislation is needed to keep the Internet neutral and open.[15]

Second the “blogosphere” still depends on daily news journalism. Therefore, cuts in newsroom staff and attempts to replace hard news with entertainment are still damaging, even in the Internet era.

NOTES

1. Bruce M. Owen, Economics and Freedom of Expression: Media Structure and the First Amendment (Cambridge, MA, 1975), table 2A-1.

2. Michael Schudson, The Good Citizen: A History of American Civic Life (New York: The Free Press, 1998), p. 6.

3. Quoted by Schudson, p. 178, who notes that Ochs also pledged to promote “right-doing” and to maintain a commitment to political principles, such as “sound money and tariff reform.” But it was the section I quote that was most influential,

4. An influential defense in English was A.J. Ayer’s 1936 book Language, Truth, and Logic. However, the prestige of logical positivism owed more to the apparently unambiguous progress of science before World War II than to any theoretical defense.

5. Burton J. Bledstein, The Culture of Professionalism: the Middle Class and the Development of Higher Education in America (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., l976); Schudson, pp. 179-182.

6. Mitchell Stephens, “Newspaper,” Collier’s Encyclopedia, 1994, available via www.nyu.edu/classes/stephens.

7. American Association of Newspaper Editors, “Examining Our Credibility,” August 4, 1999, available via www.asne.org/kiosk/reports/99reports.

8. Annenberg Public Policy Center, “Networks Only Aired About One Minute of Candidate-Centered Discourse a Night in the Days Leading to the Election: More Stories Focused on Horse-Race & Strategy

than Issues & Substance,” press release, Dec. 20, 2000.

9. James Bennet, “Polling Provoking Debate in News Media on its Use,” The New York Times, Oct. 4, 1996, p. A24.

10. Joseph N. Cappella and Kathleen Hall Jamieson. Spiral of Cynicism: The Press and the Public Good. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997)

11. Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, “Cable and Internet Loom Large in Fragmented Political News Universe: Perceptions of Partisan Bias Seen as Growing, Especially by Democrats,” January 11, 2004.

12. Peter Levine, The New Progressive Era (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2000), pp. 156-7

13. Lewis A. Friedland, Public Journalism: Past and Future (Dayton, Ohio: Kettering Foundation Press, 2003 {P???}

14. Dhavan V. Shah, Jack M. Mcleod, and So-Hyang Yoon, “Communication, Context, and Community An Exploration of Print, Broadcast, and Internet Influences,” Communication Research, Vol. 28, No. 4, 464-506 (2001)

15. Jeffrey Chester, “The Death Of The Internet : How Industry Intends To Kill The 'Net As We Know It,” TomPaine.com, October 24, 2002.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: Internet and public issues , press criticism

July 5, 2006

newspapers and civic engagement

Almost two centuries ago, Tocqueville detected a close relationship between journalism and civic engagement. Newspapers were the main news organs of his day, and he wrote that "hardly any democratic association can do without" them. "There is a necessary connection between public associations and newspapers: newspapers make associations and associations make newspapers; and if it has been correctly advanced that associations will increase in number as the conditions of men become more equal, it is not less certain that the number of newspapers increases in proportion to that of associations. Thus it is in America that we find at the same time the greatest number of associations and of newspapers."

I wanted to see whether the relationship that Tocqueville observed impressionistically remains true. Yesterday, using the 2000 American National Election Study, I found strong, statistically significant relationships between people's frequency of reading a newspaper, on one hand, and their likelihood of volunteering, working on a community issue, attending a community meeting, contacting public officials, belonging to organizations, and belonging to organizations that influence the schools (but not protesting or belonging to an organization that influences the government). To illustrate these relationships with an example: 42.4 percent of daily newspaper readers belonged to at least one association, compared to 19.4 percent of people who read no issues of a newspaper in a typical week.

I did not control for other factors, such as education. Nevertheless, it appears that residents who engage in their communities also seek information from a high-quality source--and vice-versa. Having information about current events gives one relevant facts and motives to participate; and participation leads one to seek information.

Rates of newspaper reading have fallen sharply. I realize there is nothing sacrosanct about the printed daily newspaper; websites or radio and television broadcasts could, in theory, be just as good for civic engagement. But there is no evidence that the electronic media have yet compensated for the decline in newspaper consumption.

permanent link | comments (2) | category: press criticism

February 16, 2006

Cheney and the press

Jay Rosen has the best commentary on how Dick Cheney has handled the press after the shooting accident. As a foil, Jay quotes former White House Press Secretary Marlin Fitzwater: "If [Cheney’s] press secretary had any sense about it at all, she would have gotten the story together and put it out. Calling AP, UPI, and all of the press services. That would have gotten the story out and it would have been the right thing to do, recognizing his responsibility to the people as a nationally elected official, to tell the country what happened."

Jay replies: "But Cheney figures he told the country 'what happened.' What he did not do is tell the national press, which he does not trust to inform the country anyway. ... He treated the shooting as a private matter between private persons on private land that should be disclosed at the property owner's discretion to the townsfolk (who understand hunting accidents, and who know the Armstrongs) via their local newspaper, the Corpus Christi Caller-Times."

Note the synecdoche in Fitzwater's statement: API and UPI stand for the people and the country. Cheney doesn't accept that, and neither do I--not in the age of blogs and other peer-to-peer media. A few national news organs do not have a right to be informed about anything in particular--especially since the news will get out anyway. However, Jay also argues that the old relationship between the national press corps and the White House served as a check on the latter, and that something must be able to challenge the presidency.

For my part, I have two incompatible reactions to this affair:

1. I wish Americans paid less attention to the private behavior of public officials. Private acts are easier to understand than policy, but they give poor insight into public leadership. (For instance, the accidental shooting makes a nice metaphor for Cheney's handling of the Iraq war, but anyone could have done the same thing. The connection is symbolic and basically meaningless.) Furthermore, the emphasis on private behavior distracts attention from more serious matters; it adds an unecessary element of randomness to national affairs; and it puts officials in a fishbowl, thereby persuading some good people not to enter public life in the first place.

Therefore, I wish that Bill Clinton had gotten in trouble (with his wife and perhaps with the law) for having extramarital sex with an intern in his own office. But I wish that the press and the public hadn't cared. I wish that the Lewinsky story had appeared on page A23 and attracted no notice. Likewise, in a country of active, thoughtful, and responsible citizens, no one would care about Cheney's shooting accident. They'd be too busy thinking about earmarks, FISA, and Iraq.

2. On the other hand, it is obvious that people use the private behavior of politicians as heuristics to assess their public behavior. It's easier to understand hunting accidents and sexual harrassment than energy policy and deficits. According to Robert Wuthnow, people not only judge politicians and administrations on the basis of their private behavior; they actually draw conclusions about human nature based on what they observe politicians doing.

If this is true (and impossible to change), then public officials are publicly accountable for their private behavior, just because it can affect the administration, the party, the institution, and even the nation that they serve. Then I think the following logic holds: Dick Cheney can affect public trust by how he acts in private. A proportion of the public strongly distrusts him. Therefore, he'd better try to increase their trust by going straight to the national press corps as soon as he has a problem and tearfully confessing his deepest thoughts on evening TV. It isn't dignified, but it's the way things work in a celebrity culture with low levels of serious civic engagement.

permanent link | comments (4) | category: press criticism

October 18, 2005

on overestimating the impact of the press

Paul Krugman wrote in last Friday's New York Times:

Many people in the news media do claim, at least implicitly, to be experts at discerning character -- and their judgments play a large, sometimes decisive role in our political life. The 2000 election would have ended in a chad-proof victory for Al Gore if many reporters hadn't taken a dislike to Mr. Gore, while portraying Mr. Bush as an honest, likable guy. The 2004 election was largely decided by the image of Mr. Bush as a strong, effective leader. (Article now available by subscription only.)

Many people on both the left and right agree with Krugman's causal hypothesis. They assume that journalists have some choice about how to portray the characters of politicians, and their choices affect voting decisions. It is because people buy this theory that they expend enormous energy looking for bias in the major news media and trying to influence mainstream coverage. A belief in the power of journalists' implicit judgments raises the temperature; it encourages people to be highly critical readers who focus on the "spin" in news stories.

Of course there must be something to the theory. (And the 2000 election was so close that anything could have changed the outcome, including a rain storm or fewer earth tones in Al Gore's wardrobe.) However, I believe the importance of journalists' implicit character judgments is often overstated. Most surveys find that average voters are quite inattentive to the news, to start with. News coverage is always diverse, even when there seems to be an overall tilt like the one that Krugman detects in 2000. Moreover, the spirit of news coverage is not completely under the control of journalists. Al Gore, for example, had some potential influence on the way Al Gore was covered in 2000; this wasn't simply a discretionary call by reporters.

Finally, we can almost always explain a presidential election as a result of economic indicators, leaving news coverage aside. Larry Bartels has argued that 2000, like most US national elections, was determined by the change in disposable per capita personal income (dpi) over the twelve months prior to the election. It follows that Al Gore would have won in 2000 if the Clinton administration had decided to cut taxes, thereby raising people's dpi. Instead, they decided to pay down the national debt, thereby increasing the odds that Bush would win. If anything, it is surprising that Gore got more popular votes than Bush.

If I'm troubled by anything, it's not anti-Gore (or pro-Bush) spin, but rather the way that our democratic system seems to reward borrowing and punish fiscal responsibility. By the way, Bush's popularity until now may have a lot to do with the billions he has borrowed and spent.

permanent link | comments (1) | category: press criticism

October 7, 2005

all the news that's fit to print

Jay Rosen captures one's attention with the lead to his latest post: "Just one man's opinion, but now is a good time to say it: The New York Times is not any longer--in my mind--the greatest newspaper in the land. Nor is it the base line for the public narrative that it once was. Some time in the least year or so I moved the Washington Post into that position." (And this from a quintessential New Yorker!)

Here is what I take away from Jay's argument. First, the Times represents a traditional conception of the daily newspaper as an institution that tries to extract significant information from politically powerful people and present it to a judicious public. This is not the only valid conception of a newspaper's role; I have defended a rival view (that journalism exists to promote public participation). However, if the Times has a claim to excellence, it is the conventional one.

Jay cites a series of disturbing recent cases in which the accuracy of the Times' news coverage has been found wanting: the "breakdown in controls in reporting Weapons of Mass Destruction, ... Jayson Blair, Wen Ho Lee, Paul Krugman's correction trauma." But everyone makes mistakes, and an outsider could imagine that the Times must now be tightening its internal controls.

The Judith Miller story reflects a deeper problem than mere error. As she investigated the Valerie Plame case and faced a subpoena for her information, Miller became part of a classic Washington story about the secret behavior of powerful people. The extraordinary list of her visitors in jail (John Bolton, Bob Dole, Tom Brokaw) illustrates how close she has come to power, and how tightly linked are our media leaders and politicos. Jay notes that "Miller is a longtime friend of the [Times] publisher, Arthur Sulzberger, Jr. They socialize. It's not a scandal, but it is a fact." Indeed, it is the Times' traditional role to get close to the powerful; to offer coveted space in its news columns in return for information. Thus Sulzberger, Brokaw, Bolton, Dole, and others like them move in similar circles, as do reporters like Judith Miller. Readers potentially benefit from those connections, when the Times presses to reveal as much as possible from its exalted sources. That, after all, is the heroic story of the Pentagon Papers and Times v Sullivan.

Miller, however, became a newsmaker, a decision-maker, someone with information that she could deploy strategically. She did not choose that role: a subpoena dragged her into it. However, her contacts, her friendships, and all of her tactical choices underlined her close connections to insiders and "newsmakers." This impression presented a challenge to the Times, whose role is to explain what decision-makers are up to. We want to assume that some have power and others gather independent knowledge about them; the state and the press do not mix. But here, through no deliberate choice of Miller's, the lines were blended.

It was then the responsibility of the Times to show that it was a trustworthy explainer. Every instinct should have pressed the newspaper's editors and staff to extract information about its own reporter and to explain what she had done. Instead, the Times' coverage of Miller's legal predicament has been confusing, low-key, half-hearted, and passive. Its columnists have been virtually silent. And it is has issued no meaningful public statements or press releases.

The implicit deal that the Times offers is this: We will cozy up to the power-brokers, but we will do it in your interests, so that we can keep you informed about their wheeling and dealing. When the Times becomes a power-broker itself, the deal comes into question. At that moment, the editors should understand that their whole justification is at stake, and they should rush to serve the public's "right to know." Failure to do so raises fundamental questions about the value of the New York Times that go far beyond any cases of misreporting or run-of-the-mill bias.

permanent link | comments (1) | category: press criticism

October 4, 2005

the "inverted pyramid" and other barriers to comprehension

I worked yesterday with a small group of undergrads who wanted me to help them follow current events. I asked them to read the lead article in the New York Times, because I thought it exemplified certain journalistic conventions that make it difficult for novices to understand the news.

The lead story was entitled "Macabre Clues Advance Inquiry in Bali Attacks." It began with the gruesome discovery of three heads widely separated from their feet and without extant torsos--evidence of suicide bombers. The story then mentioned the bombing in Bali that had occurred two days earlier. Next came a body count and a mention of the seven wounded Americans. The story gradually widened to include some discussion of the Indonesian group Jemaah Islamiyah, a splinter of which may be associated with Al Qaeda. After that reference came some discussion of the previous attacks in Indonesia in 2002, mixed with detailed descriptions of the wounded Americans. And finally the article explained that Bali is a Hindu island in predominantly Moslem Indonesia.

Using a version of the "inverted pyramid" style, the writers had begun with the latest facts and then widened to provide context, with the most general information saved for the very end. However, they never explained anything about Indonesia's history, politics, economy, or religious culture, or the structure and goals of Al Qaeda.

Daily newspapers are written for daily readers. I don't want an article to start with facts about Indonesian history and end with the latest from the Balinese forensic investigation. I read the news on Sunday and already know what happened then. But for a newcomer, the Times' lead story, like most of its coverage, is perplexing. The necessary factual base is either withheld until the very end or never provided at all; and the narrative logic of the story is completely shattered.

I asked the students whether the story belonged in the newspaper at all. Every day, about 153,000 human beings die. Thus it's not immediately obvious why we should all read about the 19 people murdered in Bali (or the 21 drowned on Sunday on Lake George). Publicity is just what Al Qaeda wants, and that's reason enough to question whether the bombing should be an international lead story.

By the time I had explained that it is difficult to read a standard breaking news article, and I had raised questions about whether the story was appropriate in the first place, I'm afraid I had driven these young people away from newspapers. I tried to explain why I read the Post and Times every day, but I'm afraid I wasn't too convincing (because I wasn't too convinced). I said that we each possess a general view of the world. We may see it as threatening, or divided between Islam and the West, or full of needless suffering, or stricken by Western imperialism, or united by a common humanity. Each significant news story helps us to shape, revise, and develop that worldview. In turn, our attitude guides our daily actions and choices. This is what I said, but none of it proves that the Times should have led with gruesome facts about the bodies of suicide bombers.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: press criticism

September 12, 2005

"expert" voices

I'm quoted in a recent story on Yahoo News (provided by Agence France Presse), entitled, "Katrina: US TV swings from deference to outrage towards government." The lead is, "In the emotional aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, US television's often deferential treatment of government officials has been replaced by fiercely combative interviews and scathing commentary." Some examples follow, and then I am quoted near the end:

Media expert* Peter Levine, of the School of Public Policy at the University of Maryland, said the shift in stance of American television was a return to normal following four years of toeing the government line following the September 11 attacks."After 9/11 those who publicly dissented from support of the president and the government were rounded on from all sides," he told AFP.

"The political calculation of (opposition) Democratic politicans was that it was best to support the president and so no one wanted to be seen dissenting, giving the media little to base any criticism on," he said.

But with local officials, including Louisiana Governor Kathleen Blanco and New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin openly slamming the government response to the New Orleans catastrophe, usually reserved media feel free to do the same, he said.

Added to that, the horror played out on live television belied the government's claims that its preparations for the storm and subsequent rescue effort had been sufficient.

"(Television stations) have people on the ground and are seeing a huge difference between what they are being told by officials and what they are actually seeing," Levine said.

None of this is profound or original, but it exemplifies the phenomenon I meant to describe. The reporter probably had the thoughts that he attributed to me before I said them. But he could not simply write those ideas down in his own words, because that would be editorializing, interpreting, or analyzing, and he couldn't do that as a reporter. His assignment was to record facts, such as what a "media expert" had said. So he called around until he found someone who told him something that he wanted to say himself, and then he quoted that person--in this case, me.

Between Sept. 11, 2001 and the Iraq invasion, relatively few of the people whom reporters quote were willing to say anything bad about US foreign policy, and that is why critical perspectives were so rare.

*My media "expertise" comes solely from regular reading of The New York Times, including the news, arts, op-ed, NY region, and business sections and the obituaries, but rarely the sports and never the new "style" section, which I condemn unequivocally.

permanent link | comments (1) | category: press criticism

August 30, 2005

the press and political power (thoughts on Jay Rosen/Austin Bay)

Recently, Jay Rosen asked Austin Bay ("Weekly Standard writer, NPR commentator, Iraq War vet, Colonel in the Army Reserve, Republican, conservative, blogger with a lit PhD") to guest-blog about the press, the Bush administration, and the war. Bay's long post provoked a total of 441 comments on Jay's site and 45 on Bay's blog (so far). I haven't read all the comments, but it appears that they generated more heat than light. In particular, there was a lot of passionate discussion of the media's alleged bias against Republicans, little of which--on either side--seemed particularly illuminating. But Bay's original essay was interesting, and I would like to address his thesis from a different angle.

Bay proposes that the United States is locked in an "information war waged by an enemy that is itself a strategic information power," namely, Al Qaeda. The American press has an influence on that war. How it presents the American military, Guantanamo, the Iraqi election, and other key matters will help determine whether people around the world embrace Bin Laden, Bush, or some alternative. And what ideology people adopt is the key question in this "war."

Meanwhile, the Bush Administration and conservatives have a very bad relationship with the mainstream American news media. To a large extent, Bay blames journalists for the poor state of that relationship, arguing that they are biased in liberal, urban, and civilian directions. Nevertheless, he argues, the Bush people need the press to support the long-term struggle against Al Qaeda and Islamic extremism, or else we will fail:

America must win the War On Terror, and the poisoned White House—national press relationship harms that effort. History will judge the Bush Administration’s prosecution of the War On Terror. A key strategic issue for the current White House–perhaps a determinative issue for historians–will be its success or failure in getting subsequent administrations to sustain the political and economic development policies that truly winning the War On Terror will entail.

Bay, a conservative pundit who is angry at the "liberal media" and presents a long bill of specific grievances, nevertheless recommends that the Bush Administration try to improve its relationship with journalists.

Now, here's my response. First, the press powerfully helps or hinders American presidents and administrations in achieving their policy goals. It is not neutral, although it can be diverse. Second, the relationship between the press and the White House has changed dramatically, in ways that make life more difficult for presidents.

The period from 1945-1965 remains a benchmark for those who want the press to be more supportive of the US military and presidency. But it is important to note that the stars were then aligned to the benefit of presidents Truman, Eisenhower, and Kennedy. There was virtual consensus about foreign policy and national economic policy (which everyone wanted to be Keynsian). To be sure, there were wrenching national debates about Jim Crow and McCarthyism/Communism, but the leaders of the two national parties tended to adopt similar positions on these matters, positions that were also shared by the editors of The New York Times and like publications. All these people knew each other: they were white men who tended to graduate from the same schools and colleges. Reporters were aware of, but left completely unreported, politicians' personal problems and faults. The national press also imposed on itself a set of norms that were then only about 50 years old: nonpartisanship, a separation of news from opinion and fact from fiction, and objectivity (epitomized by the suppression of first-person reporting). Reporters tended to take leaders at face value and report their explicit arguments; they did not reflexively interpret everything a politician said as a ploy to obtain votes. Perhaps most important, the American people trusted the government, as the following trend lines show.

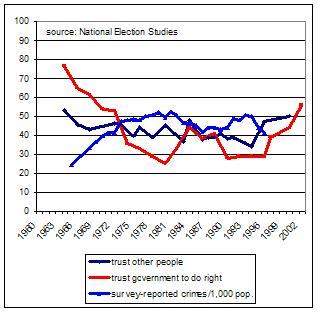

Trust in government correlates with trust in other human beings (r=.17 in the National Election Studies); and many people did trust their neighbors in an age of prosperity, high associational membership, clear memories of World War II, and relatively low crime and divorce. (Note the huge increase in per capita crime after 1963, shown above.) I don't mean to romanticize America ca. 1960, when gross inequalities were papered over. I only want to argue that life was relatively easy for political leaders, because the press and public alike tended to support them and overlook their foibles.

All of this changed after 1965. Public trust in the government fell. The parties became more ideologically consistent and polarized. Public consensus on foreign policy crumbled. As Dan Yankelovich writes in Foreign Affairs, "Americans are at least as polarized on issues of foreign affairs as they are on domestic politics. They seem to have left behind, at least for the time being, the unity over foreign policy that characterized the World War II era and much of the Cold War period. As might be expected, Americans today are split most sharply along partisan lines on many (though not all) aspects of U.S. foreign policy." Particularly interesting is the 43-point gap between Republicans and Democrats on whether the US is "generally doing the right thing with plenty to be proud of" in foreign policy.

After 1965, the press chalked up what Bay calls two "great gotcha successes": Vietnam and Watergate. Perhaps those powerful exposes lowered public trust and helped turn journalists into skeptics of government. Or perhaps--as I suspect--journalists belong to our culture, and America as a whole was turning anti-authoritarian, skeptical of power, and less trusting of human beings in general. The modern journalistic "frame" which interprets all political behavior as strategic and self-interested comes, I think, out of our broader culture and not just out of J-schools and news rooms.

Bay argues this is how the press now operates:

Rule One: Presume the U.S. government is lying–especially when the president is a Republican. Rule Two: Presume the worst about the U.S. military–even when the president is a Democrat. Rule Three: Allegations by 'Third World victims' are presumptively true, while U.S. statements are met with arrogant contempt.

Reflecting on how the national press treated Bill Clinton, or how the Washington Post covers local political leaders (who are mostly African American and Democratic), I would say that the rules are:

Rule One: Presume all powerful people are self-interested, and everything they say and do is calculated to win them votes. Rule Two: Look for scandal and failure in all public institutions: schools, the military, welfare systems, the police. Rule Three: Always report allegations against political leaders (followed by their denials) on the assumption that conflict between potentially victimized citizens and potentially crooked politicians is a major form of "news." Don't pay as much attention when citizens agree with one another or work together to address problems.

Evidently, my take is somewhat different from Bay's, but the difference doesn't matter much. There is little doubt that the modern press makes life more difficult for any American president than it once was. It has not become more difficult to be elected or re-elected. After all, someone has to win, and one side will beat the other at the media game. But it is more difficult to realize an ambitious agenda. I'm not sure that Truman, Eisenhower, and Kennedy could have built the interstate highway system, desegregated schools, conducted large-scale, undeclared "police actions," and imposed 90% marginal income tax rates without a supportive and gentle press. Those days are gone.

So what lesson should we draw? I suspect that many of my readers are glad that trust has fallen, recognizing that the U.S. government has done many bad things when not overseen by a skeptical, watchdog press. If anything, many people wish that the press had been much more skeptical of the Bush administration in the run-up to the Iraq war. (Note that public confidence in government and social trust were relatively high in 2002, just when the press was being deferential.) Many people are glad to see the president's approval ratings fall and the press get tougher.

I fully accept that argument, and yet it strikes me that liberal presidents also have a harder time governing when the press is antagonistic to power. In fact, it isn't because Bush has pursued conservative policies that he has tangled with the press. His tax cuts get relatively little coverage, positive or negative. It was when he embarked on a radical, state-led social experiment by invading Iraq that the press pounced, because journalists are always ready to expose the weaknesses of government. I'm against the war in Iraq, but I'm afraid that the attitudes of the mainstream press that Bay dislikes are actually worse for liberals than for conservatives.

Besides, we do need to win an information war against Bin Ladenism, and journalists ought to figure out what their role is going to be in that struggle.

Their coverage will affect international opinion--as well as domestic opinion about matters like civil liberties. They are not innocent or politically powerless. So where do they intend to stand?

Above all, we might ask whether the big decline in public trust is a good thing. Hamilton proposed as a "general rule" that people's "confidence in and obedience to a government will commonly be proportioned to the goodness or badness of its administration." If that is true, then the decline in trust since 1960 was merely a measure of the falling trustworthiness of government. Perhaps--but again, a failure of government is worse news for liberals than for small-government conservatives.

permanent link | comments (0) | category: press criticism

July 18, 2005

moral standing

Like many news stories, this one began when an influential local figure made remarks that were seen as offensive. Willie F. Wilson, former mayoral candidate and current pastor of a Southeast Washington Baptist church, said in a taped sermon that "lesbianism is about to take over our community. ... Sisters making more money than brothers and it's creating problems in families ... that's one of the reasons many of our women are becoming lesbians. ... I ain't homophobic because everybody here got something wrong with him. But --" and he proceeded to make disparaging remarks about gay sex which I'd rather not paste on this PG-rated website.

By the following Sunday, according to the Washington Post, "TV trucks were in front of the church and reporters were in the pews," waiting for Rev. Wilson's apology. But he said, "I ain't got nothing to say to you. You don't know us. You don't care about us. Get off this phone. Don't call me no more."

Let me stipulate: a) I don't condone the Reverend's comments, and b) reporters and other people have a legal right to ask questions about what he said and to request an apology--the First Amendment covers their speech and allows them to stand outside the church. But these are my questions: Is the content of a sermon anyone else's business? Is it appropriate for those TV trucks to park outside the church, demanding a public response? When does speech become "public" in the sense that the speaker owes an apology if what he says is wrong or offensive?

On the one hand ... There is a lot of violence and discrimination against gays. While Rev. Wilson's sermon did not explicitly incite mistreatment of lesbians, the minister used his religious authority to denigrate gays, which surely increases their vulnerability. Since the clergy have a First Amendment right to say bad things about gays, the only possible response is for gay people--and their straight supporters--to intervene rhetorically. Thus it's appropriate to quote Rev. Wilson's speech, to criticize it, to ask him to apologize, and to stick TV microphones in his face.

On the other hand ... I am moved by Rev. Wilson's statement about the media: "You don't know us. You don't care about us." Even if what he said was completely wrong (factually and morally), that doesn't mean that reporters have standing to make an issue out of it. It's not as if the daily work of the Union Temple Baptist Church gets much coverage in the Washington Post. (There have been 443 mentions of the church since 1987, but most appear to be very incidental.) The whole neighborhood tends not to be covered unless murders occur there. The Post has no ongoing relationships with the congregation.

When reporters decide to quote a statement, and then call other people who may be offended to get their responses, they are making a choice. They are claiming an oversight or "watchdog" role with respect to the person who spoke. If they heard a teenager making an anti-gay slur while walking down the street, they would not write an article about it. They surely should tell us if an elected official utters a slur, even in private. Their decision to quote the Rev. Wilson's sermon shows that they believe that what goes on inside his church is public business. But on other occasions, they don't treat his congregration as if it had public importance.

I confess that I am protective of Union Temple Baptist Church and its privacy because I generally feel that the press is unfair and unhelpful to poor, African American urban communities. They only show up at the embarrassing moments. However, what Rev. Wilson said--"You don't know us. You don't care about us"--could also be said by a white fundamentalist preacher in the suburbs.

permanent link | comments (3) | category: press criticism

July 13, 2005

why I don't care about Karl Rove

If Karl Rove committed a crime, then he should face the consequences, and it's a matter for the criminal justice system. It's a different question whether the rest of us--the press, the political parties, and the public--should focus attention on this case. I say no, for the following reasons: