« November 2008 | Main | January 2009 »

December 31, 2008

The Winter's Tale

Reading The Winter's Tale this week reinforced my sense that Shakespeare, in his last years as a playwright, was worried about the power of a dramatist to influence people's passions and make them believe falsehoods. In both The Winter's Tale (1610-11) and The Tempest (1611-12), this power is seen as political and as morally ambiguous. The issues that concern Shakespeare remain alive today, although now the medium that is most problematic is film rather than live theater.

The Winter's Tale has a fantastical plot. It's a fairy-tale, involving an abandoned and miraculously rediscovered princess, a talking statue, and even a bear that appears without warning and devours a significant character. Whereas Shakespeare took most of his plots from purported works of history, this one was obviously a fiction--both because it was unbelievable and because the original authors were recent Englishmen. Only The Tempest belongs as clearly to the category of fiction.

One problem with telling a fictional story in an engaging way is that you thereby make people believe what is not true. This power has often made moralists uncomfortable. According to Plutarch, when the very first tragedies were performed, Solon attended and asked Thespis, the first playwright, "if he was not ashamed to tell so many lies before such a number of people."

In Shakespeare's time, Sir Phillip Sidney defended fiction on the ground that it was not the author's intention to deceive. "The poet, he nothing affirms, and therefore never lieth. For, as I take it, to lie is to affirm that to be true which is false." As author of Astrophel and Stella, Sidney was not a liar because he could count on his readers not to believe the plot. But in the midst of an effective theatrical performance, the audience will suspend disbelief. It is the playwright's goal to make that happen.

Apart from the moral disadvantage of making people believe in lies, there's also the practical problem of overcoming their skepticism and making a play "work." Shakespeare was surely aware of the latter challenge. Throughout The Winter's Tale, characters are incredulous about what they see. One important scene is not enacted but rather narrated by minor characters, one of whom says, "this news which is called true is so like an old tale, that the verity of it is in strong suspicion." There is even a comic subplot about a trickster, Autolycus, who sells fantastical tales to rustic fools:

- AUTOLYCUS: Here's another ballad of a fish, that appeared upon the coast on Wednesday the four-score of April, forty thousand fathom above water, and sung this ballad against the hard hearts of maids: it was thought she was a woman and was turned into a cold

fish for she would not exchange flesh with one that loved her: the ballad is very pitiful and as true.

DORCAS: Is it true too, think you?

AUTOLYCUS: Five justices' hands at it, and witnesses more than my pack will hold.

Shakespeare is aware that his plot is unbelievable, yet he also knows that an audience will be absorbed in his fairy tale. Even today, we care about the characters and hope for a happy ending as long as the curtain is up. That is a power akin to magic.

Some of the events of the play are sheer accidents. But several are contrived by characters who work behind the scenes. Paulina, above all, is an orchestrator of events. It is because of her art (not by magic or coincidence) that Hermione vanishes for 16 years and reappears at a dramatic moment. Paulina is probably responsible, too, for Hermione's rather disturbing appearance to her husband as a ghost who prophesies his death (III.3.18ff). If Paulina provides lines for the real Hermione to recite to her spouse, then Paulina is a chillingly effective playwright. She is also a cause of Perdita's banishment, since she brings the baby before the king as a kind of tableau that is supposed to draw his sympathy. That drama fails, but the final tableau that she stages (with the talking statue) is a success, both dramatically and morally.

Paulina is a teller of lies--for instance, she announces falsely that Hermione is dead--but she is also a very blunt teller of truth. For instance, although everyone else uses tactful euphemisms for death and murder, Paulina is starkly literal:

- PAULINA: True, too true, my lord:

If, one by one, you wedded all the world,

Or from the all that are took something good,

To make a perfect woman, she you kill'd

Would be unparallel'd.

LEONTES: I think so. Kill'd!

She I kill'd! I did so: but thou strikest me

Sorely, to say I did; it is as bitter

Upon thy tongue as in my thought: now, good now,

Say so but seldom.

Paulina's mixing of blunt fact with elaborately staged fiction may be problematic, in Shakespeare's eyes. Perdita is a straightforwardly good character, and she disdains even carnations because they mix human art with nature (IV.4.82).

Paulina, like Prospero in The Tempest, is a playwright within the play. Both characters are on the side of right or justice. But both are disturbing figures who exploit minor characters, have forceful personalities, and go to elaborate lengths to plan cathartic dramas across long spans of time. I wonder whether Shakespeare considered his own art equally disturbing and wished to be more like the simple and straightforward daughters in these two plays.

Posted by peterlevine at 1:23 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

December 30, 2008

Rick Warren at the Inauguration

I thought Frank Rich's response to the Rick Warren controversy was very strange. In the New York Times, Rich wrote that asking Warren to give the invocation at the inauguration "was a conscious--and glib--decision by Obama to spend political capital. It was made with the certitude that a leader with a mandate can do no wrong." It was, Rich said, rather like George W. Bush's high-handed dismissal of moderate and liberal voters at the outset of his administration. And "we all know how that turned out."

I would have thought exactly the opposite. Obama seeks to obtain political capital by inviting a conservative evangelical to speak at his inaugural, thus reassuring Americans who think that the President Elect is a Muslim, or else secular and hyper-liberal. He might also hope to peel some conservative voters away from the Republican coalition. Far from arrogant or spendthrift, this was a rather calculated, cautious, and defensive political move. The people it might offend (i.e., supporters of gay rights) are outnumbered by the people it might attract; and more to the point, the former have nowhere else to go, whereas the latter are potential swing voters. If I were criticizing Obama, I would assail him for unprincipled caution rather than arrogance.

My actual views are more ambivalent. I do understand that it's hurtful to give a ceremonial role at a public event to a person who is not only against gay marriage, but who compares legalizing it to legalizing incest. I suppose a rough equivalent would be an anti-Semitic speaker--but gays are far more victimized by discrimination and violence than Jews are in modern America. So that's a big argument against inviting Rick Warren.

On the other hand:

1. The political advantages are considerable, since evangelicals really could splinter, and liberals could pick up their votes. The Bible is not for tax cuts; the Bible is for stewardship, education, and the poor.

2. Warren used words about gay marriage that are indefensible (and that he apparently regrets), but his actual position cannot be considered beyond the pale. Most Americans share that position. Warren also shares with most Americans the opinion that religious scriptures are authoritative. The Hebrew Bible and the New Testament are pretty strongly against gay marriage. I could make a theological argument in favor of gay marriage, basing my position on a certain reading of the whole biblical canon. That reading would be tendentious, although sincere. I think Rick Warren, an evangelical pastor, is entitled to his more traditional and more straightforward reading of a text that he is entitled to use as his guide.

3. This invitation has hurt people, and I am sorry about that. It has also opened some healthy conversations, such as the one between Rick Warren and Melissa Etheridge. Bishop Gene Robinson and others have noted that an invocation is not a dialog or a deliberation. Robinson said, "I'm all for Rick Warren being at the table, ... but we're talking about putting someone up front and center at what will be the most-watched inauguration in history, and asking his blessing on the nation. And the God that he’s praying to is not the God that I know." I would respond that Warren shouldn't be excluded for praying to the wrong God (if that even makes sense); and that asking him to speak was an indirect way of bringing him to the table on this issue.

There are several kinds of politics at work here. Gays are rightly trying to develop a public identity and asking for it to be favorably received. From the perspective of that "politics of identity and recognition," Warren's invitation is harmful. Meanwhile, Obama is trying to develop and expand social programs. For that "politics of distribution," the Warren invitation is smart. And various people are discussing a controversial issue: gay marriage. The Warren invitation is a spur to that "politics of deliberation." Much depends on which we think is most important. It's not surprising that Frank Rich would opt for the first choice, since he is an almost perfect representative of liberal identity politics. What I do find surprising is his failure even to notice the other kinds of politics in this case.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:35 AM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

December 29, 2008

travelers for quiet airport terminals

I spend many of my hours in airports, trying to read, write, or talk quietly. Very often the following noises are laid on top of each other:

- Boarding announcements

- TSA security announcements

- Music

- The CNN Airport Network on overhead TVs

- Promotional announcements about the airport or city

- Beeping trucks

- People's voices, and

- (Unnoticeable but apparently quite audible) the sounds of the airplanes themselves.

I don't mind my fellow passengers--not even the screaming babies, who are expressing my own feelings with simple eloquence. It's the unnecessary layers of noise that offend me, especially when I learn that airports derive revenue from that piped-in TV advertising. Not only is the combination of CNN plus music-radio jarring and distracting; the actual content of the news is insidious and often inappropriate for kids. Sometimes one can lower the decibel level by shifting location, but in some airports (e.g., Dayton, OH), CNN is pumped everywhere, including the toilets and the business lounge.

Airports are local monopolies, subsidized by tax dollars but basically unaccountable to consumers. They profit from advertising and pay no price for noise. They may create health risks by exposing people to noise. They certainly reduce productivity by making it hard to concentrate. Noise-canceling headphones haven't worked for me, and even if they did, what gives an airport the right to make me wear expensive and uncomfortable hardware?

I'd favor a legal remedy--possibly a class-action lawsuit on behalf of airport workers or an amendment to such legislation as the Noise Control Act of 1972 or the Airport Noise and Capacity Act of 1990. (The latter deals with aircraft noise and seems mainly aimed at blocking local anti-noise regulation.)

Meanwhile, we travelers can at least express our opinions--I would say, "raise our voices," if I weren't trying to increase the peace. There is already a lobby that fights the noise of aircraft landing and taking off. That's a problem that harms finite, identifiable minorities (homeowners in affected neighborhoods), who are therefore likely to organize in their own interests--even at some cost to the average person. Airport noise is a different kind of problem. It sporadically harms many people, but not enough for them to organize. Fortunately, the Internet lowers the cost of organizing. I just created a Facebook page called "travelers for quiet airport terminals." I hope like-minded people will join and post complaints, praiseworthy examples, tips for finding quiet spots, and strategies for reform.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:21 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

December 24, 2008

happy holidays

This is actually a movie from our 2006 family trip to Rothenburg ob der Tauber, Germany. I hope it brings cheer (even to those, like me, for whom neither Christmas nor Bavaria is unambiguously good).

Posted by peterlevine at 2:18 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

December 23, 2008

civic innovation in Britain

I've written before about the civic agenda of the current British government, which includes better civic education in schools, decentralization of power, and innovative opportunities for citizens' work. Via Henry Tam, here is a government paper entitled "Communities in Control: Real People, Real Power." It's a long and detailed paper, but here are some highlights:

- Participatory budgeting is a Brazilian invention; citizens are invited to meetings where they can collectively allocate portions of the local capital budget to purposes of their choice. In Brazil, participatory budgeting has increased the fairness of public-sector spending and has reduced corruption. It is now being used in 22 local councils in Britain, and the UK Government wants it to be used everywhere. (I believe that the Obama Administration should build Participatory Budgeting into its economic recovery plan.)

- Citizens Juries are randomly selected bodies of citizens who meet for a substantial amount of time, deliberate, and make public decisions. Citizens Juries are now being used in the UK. A recent comment on this blog suggested that they are a strategy to avoid the traditional forms of representation, such as students unions, which are less tractable. That's possible, but there have been very impressive experiments with Citizens Juries in other countries.

- The Government intends to implement a "duty to involve" rule that would apply to most local service-providers. That reminds me a bit of the "maximum feasible participation" mandate of the War on Poverty in the US during the 1960s. Maximum feasible participation was hardly a clear-cut success, but one interpretation is that we did not yet have a sufficient infrastructure (set of practices, institutions, and trained people) to handle it. The infrastructure has improved over the last 40 years--probably in the UK as well as here.

- The paper acknowledges the importance of "strong independent media" and promises support for "a range of media outlets and support innovation in community and social media." It's tricky for a government to intervene in the news media. One must consider freedom of the press and expression. On the other hand, the 20th-century local media system is collapsing, and governments should find ideologically and politically neutral ways to promote healthy local news and debate.

- One of the major themes is civic renewal through decentralization. Gordon Brown has argued that the 20th-century Labour Party erred by trying to implement democratic socialism in a state-centered, nationalist form. In the developing world, centralization promoted various forms of corruption, whereas decentralization has lately permitted citizens to play more constructive roles.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:48 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

December 21, 2008

impeach Blago

(en route to Georgia for the holidays) The effort to impeach Gov. Blagojevich seems to have stalled, on the ground that the legislature cannot find him guilty of corruption without a lengthy trial--complete with an elaborate defense--that might undermine the federal prosecution.

I'd make this simpler. I'd move to impeach and remove Gov. Blagojevich without presuming or showing that he's guilty of the charges in the indictment. I'd impeach him because he's been indicted and he cannot perform the state's business in that condition. A governor could be falsely indicted--he could be completely innocent. However, if the indictment concerns a felony that relates to his position, he should probably resign to concentrate on fighting the charges and to save the state from being led by a criminal defendant. That might not be the best decision in every conceivable situation--for instance, a prosecutor might bring transparently baseless felony charges just to force a resignation. But it seems within the competence of the legislature to decide that this particular indictment is plausible and that Blagejovich cannot serve. That sounds like grounds for impeachment to me, and it should take just a couple of hours to do the deed.

Two obvious objections arise. (1) The impeachment could deprive an innocent man of his rights. I reply: No one has a right to be governor. That is a privilege. One should only hold the office if doing so is good for the people of the state. Even if Blagojevich is innocent, it is not good for Illinois for him to serve. (2) A politically motivated legislature could remove a governor simply because they didn't like him. I reply: that would be wrong, and the people should punish such a legislature at the next election. But it's not the situation here. The legislature deeply disliked Blagojevich months ago, but they didn't think about impeaching him. They should impeach him now because any person indicted for felonies that directly relate to his public duties cannot credibly perform those duties. It's time to get this over with.

(By the way, Kenneth Starr never indicted Bill Clinton.)

Posted by peterlevine at 6:54 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

December 19, 2008

what if you hold a deliberation and corporations show up?

I come out of the movement for deliberative democracy. My first job was with the Kettering Foundation, which launched the National Issues Forums; and I have also worked with AmericaSPEAKS, Study Circles, and other organizations that promote public deliberations. Deliberative forums vary in size, duration, organization, and methods of recruitment, but all try to draw representative (or at least diverse) groups of citizens. Since people attend to decide what should be done, not to represent interests or advance causes, their statements are presumably sincere. In contrast, participants in negotiations may have ulterior motives. Deliberations usually seem better than "politics as usual"--more civil and constructive, driven by better motivations.

But is this because they are "deliberations"? Or is it because they are low-stakes affairs, with no direct consequences for policy? As the stakes rise, what happens to deliberations and deliberators?

According to Robert Pear in the New York Times, volunteers from the Obama Campaign are organizing 4,200 small meetings ("house parties") to discuss health care. I wouldn't call these events "deliberations," because one side in the debate has set the agenda. But they are somewhat deliberative in structure and intent--and they are open to anyone who wants to come. Whether or not we call them deliberations, they are participatory free spaces for open dialogue, and they have the potential to strengthen neighborly connections. So they are Good Things.

In response, the insurance companies are "encouraging [their] employees and satisfied customers to attend" the Obama house parties. Insurance companies have First Amendment rights to petition and assembly. If someone organizes an open discussion, corporations are entitled to send their members. An obvious counter is to make sure that even more people come who have pro-reform beliefs. At that point, a "house party" starts looking like a conventional democratic assembly, caucus, or election, in which the point is to turn out the greatest numbers. That is not, of course, a bad system: we tend to call it "democracy." But we already have a structure for it, composed of numerous electoral districts, levels of governance, and rules for open meetings, oversight, judicial review, etc., etc.

My point is not a skeptical or cynical one. I think pure deliberations are valuable, and so are the quasi-deliberative "house parties" that the Obama volunteers are organizing. I also think town meetings and legislative assemblies are good. I simply expect different norms to arise when there are different kinds of stakes. We should not romanticize entirely voluntary events that have wonderful atmospheres but don't affect policy.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:13 PM | Comments (3) | TrackBack

December 18, 2008

on cutting and growing

- Cuttings

Sticks-in-a-drowse over sugary loam,

Their intricate stem-fur dries;

But still the delicate slips keep coaxing up water;

The small cells bulge;

One nub of growth

Nudges a sand-crumb loose,

Pokes through a musty sheath

Its pale tendrilous horn.

Theodore Roethke, "The Lost Son and Other Poems" (1948)

An aphorism is a "cutting," because the Greek verb aphorizdo is to "cut." So a book of aphorisms is a selection of short pieces cut and pasted together. Wittgenstein was in the habit of writing short passages, cutting them out with scissors, and throwing them in a box. The results were published as a book entitled "Cuttings" (Zettel) which might be considered an unpretentious word for "aphorisms." That form had attained high esteem but also some pomposity with Schlegel, Kleist, Karl Kraus, Walter Benjamin, and other German authors.

Blog posts are also "cuttings" in this sense. I think many people who write or read blogs would be embarrassed to call them "aphorisms," but they hope that the juxtaposition of short snippets of text will be generative, like sticks in wet soil. Good blogs are contributions to something more ambitious and more coherent. Our quick and scattered thoughts have the potential to come together in linear form. Which brings up another meaning of a "cutting"--a piece of a plant that could begin to grow. Theodore Roethke explores that meaning in remarkable pendant poems from 1948.

- Cuttings (later)

This urge, wrestle, resurrection of dry sticks,

Cut stems struggling to put down feet.

What saint strained so much,

Rose on such lopped limbs to a new life?

I can hear, underground, that sucking and sobbing,

In my veins, in my bones I feel it, --

The small waters seeping upward,

The tight grains parting at last.

When sprouts break out,

Slippery as fish,

I quail, lean to beginnings, sheath-wet.

Theodore Roethke, "The Lost Son and Other Poems" (1948)

In both poems, especially the latter, the verbs are hard to distinguish from the nouns. In "Cuttings (later)", the words "urge," "wrestle," and "cut" are used as nouns. That first sentence has no verb at all. In line three, "strained" is a verb, but it first struck me as an adjective. Plants, of course, are objects; we think of action taking place in the animal kingdom, which is also the realm of suffering. But vegetable cuttings are acting when they begin to sprout--they need verbs. Roethke's language represents the pain of moving into action, of nouns taking on verbs. The verse shifts from objective description (about the plants) to Roethke's own response. The two poems are themselves cuttings, separated from each other in the original volume, removed from any lengthy narrative or argument, but straining to grow and to inspire growth.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:49 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

December 17, 2008

the European city as site of citizenship

I met yesterday with a German visitor, a former mayor as well as an activist shaped by the sixties and by direct exposure to the Frankfurt School. We talked about European self-governing cities as sites of citizenship.

There is a very old tradition of autonomous or quasi-autonomous European cities, governed by guilds and associations (corporations; comuni; freie Städte). It was in the medieval Italian city-states that civic republicanism was reborn, in imitation of classical ideals of eloquent deliberation, military and civilian service, and mutual obligation. Autonomous European cities also built an impressive array of institutions: hospitals, churches, alms houses, schools, colleges, and green spaces. By the seventeenth century in the Atlantic countries, and by 1900 in Central Europe, all these cities had become subject to large nation-states, managed from their metropolitan capitals. But even in Britain, where power and population shifted early to London, the provincial cities continued to construct impressive nonprofit and public institutions that reflected and developed their local cultures and continued local traditions of governance. Lord Mayors in British cities still wear medieval or renaissance garb, for a reason.

The twentieth century, as Gordon Brown has noted , was an era of centralization. Social democrats, conservative nationalists, and even Thatcherite neoliberals all generally disparaged or ignored the traditions of civic autonomy. But those traditions could be revived--and may be reviving--as the European Union draws power away from the nation state. Brown, a Glaswegian, has explicitly evoked the civic traditions of his city in Victorian times, before his own party helped to centralize authority in London.

Ambrogio Lorenzetti, "The Effects of Good Government on the Life of the City," in the Palazzo Publico (seat of the comune), Siena

Shouldn't we worry that citizenship defined by a town or city is exclusive? What about immigrants and other newcomers? That is a concern, but it's worth noting that some of the old self-governing cities (from Venice to London) were highly cosmopolitan, and cosmopolitanism was basic to their identity. I recognize that London apprentices used to riot against Flemish and Huguenot migrants; and Venice coined the very word "Ghetto" as the place to lock its Jews. But there were also traditions of inclusion. I may be over-influenced by personal experience, but I happened to attend a primary school within the medieval limits of the City of London, where the Christian socialist headmaster taught his rather diverse student body to see themselves as citizens of the ancient corporation. A recent Lord Mayor of that same corporation had exactly my (Jewish) name, Peter Levine. As a child, I was proud of my American identity but could simultaneously consider myself a Londoner, because London has always been a melting pot.

But wasn't civic government highly stratified and unequal, with local ruling classes lording it over local proletariats? Again, that's a real concern; but I would offer two responses. First, cities should not be completely autonomous. They should be taxed, regulated, and funded by higher levels of government whose principles include fairness and equality. Second, although I favor equality, I also believe that the owners of capital need discretion and will always have a privileged position. So our goal should not be to remove inequality but to tie the interests of the wealthy to those of the community. The wealthy class in a proud and quasi-autonomous city is more embedded and accountable than the wealthy class in a large nation state or an international market.

Finally, as Steve Elkin argues, municipal politics is an excellent school of democratic citizenship. The scale is big enough, and the institutions are formal enough, that every kind of issue arises--from economic redistribution to morals to global warming. But the scale is modest enough that problems are concrete and citizens have opportunities for personal leadership and face-to-face interaction.

Overall, this is an argument for what the Europeans call subsidiarity (pushing authority down to the lowest practicable level) as way to address the "democracy deficit" and restore a sense of active citizenship.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:06 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

December 15, 2008

casualties of Wall Street

I had written the following post last night, and today the same story is on the front page of the New York Times. ...

CIRCLE once received a smallish grant from the JEHT Foundation (which stands for Justice, Equality, Human Dignity, and Tolerance). JEHT funded lots of other work in the areas of criminal justice and fair elections. Alas, its donors' funds were managed by Bernard L. Madoff, the alleged Wall Street swindler. The funds are gone and JEHT has closed, apparently forever.

I serve on the board of several nonprofits and I work (in various ways) for several more. Almost everyone who holds a management position in one of these organizations is cutting programs or even laying people off. I have no solutions, forecasts, or advice, but I feel this blog should reflect the main reality of our field right now.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:12 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

unequal starts

Last week, we joined about 250 other parents in the bleachers of the Belmont (MA) High School gym. Spread across the floor were musical bands ranging from elementary school beginners to the high school's wind ensemble. The bands took turns playing for more than two hours. While they waited, the 5th- and 6th-grade musicians near me were all reading books--flopping around in their chairs but quiet and intent on their fiction. A little further away, the 7th- and 8th-graders mostly had big textbooks out and were doing homework. Even though there were about 500 people in the room, the only significant background noise was an occasional infant's cry.

These hundreds of children and parents were all focused all evening on the reading and performance of music and other texts. The whole event was intentionally "developmental"--the 9-year-olds could hear the expertise and success of the high school seniors, who were asked to help the younger kids with their instruments and stands. It was a community-wide function, combining kids from three levels of public school and a significant local nonprofit organization. We were witnessing only about one third of the whole enterprise, because there are equally large events for string ensembles and choruses, not to mention a parent/teacher band.

I suppose one could criticize the program. It takes a lot of parents' time. Scheduling lessons can produce family stress. These kids are not learning how to organize their own activities because so much of what they do is organized for them. (I write this not at all as a personal complaint but because of the work of the sociologist Annette Lareau.) One could also criticize the music, most of which is written by very minor band composers.

But overall, surely, Belmont Bandarama Night is a model of success and achievement. Kids are receiving massive investments--not only from their well-funded schools, but also from their own parents and other volunteer adults. The investments take the form of time, attention, skill, and awareness of prevailing status markers--each as important as cash. The kids respond with intellectual discipline. Even the teenagers are willing to act publicly in ways that please adults. For instance, the high school chorus recently dressed in medieval costumes to sing downtown. In some communities I can think of, you'd be beaten up for wearing doublet and hose and singing "Greensleeves." These youth will win prizes, pass tests, attend colleges, and enter the middle class, replicating their parents' social position. Cultural capital will appreciate and be inherited.

At our child's old school in Washington, DC, there were some highly privileged families. Wealth in DC comes from office work (not, for instance, directly from extractive industries), so the upper-middle-class parents mostly have advanced degrees. As in Belmont, they transmit skills and culture to their children. But their methods are usually private--individual piano lessons, for instance, or family vacations overseas. The parents who can invest lots of cultural capital are a minority. There is a huge class gradient. No one would be able to pull off a 2-hour band concert for 250 kids and expect the ones who were waiting to read quietly. Such an event would be cheerful, enthusiastic, but also noisy and chaotic. Some of the kids who were disengaged would be mocking the ones who were trying hardest to comply. There would be enormous differences in musical proficiency, discipline, engagement, and attentiveness.

Within a city like DC, there are certainly institutions (for instance, churches, mosques, small charter schools, and successful sports teams) where all the kids are on task. But these are not community-wide places. They succeed in part by setting high barriers to entry.

I like Belmont, but I honestly prefer the culture of a big-city school system. I appreciate the diversity--not only of race and ethnicity but also of trajectories through life. I admire the way kids improvise their own activities and status markers. Still, Belmont's children have enormous advantages for the 21st-century work world. They benefit not only from smoothly functioning, well-funded schools but also simply from growing up in a jurisdiction that consists of middle-class, education-obsessed families. I'd love to mix the Belmont families with others, but I think we've learned from 50 years of experience that parents will sort themselves by social class. We can't tell Belmont to stop providing a rich, challenging, developmental structure for all its children--that would be tyrannical and also counterproductive. We can't purchase the Belmont band program for a poorer district, because most of what sustains it is parental involvement.

Finally, we shouldn't simply export Belmont's norms. Some forms of culture are objectively excellent--like Mozart and Ellington. And some general approaches to education are always wise--such as providing a coherent developmental pathway from childhood through adolescence. But there were many aspects of the Belmont Bandarama (not only the music played, but also the way it was advertised, presented, and taught) that are arbitrary. They fit in a certain cultural context--suburban, middle-class, secular, and predominantly European- and Asian-American. They need not fit elsewhere.

The problem of unequal cultural capital strikes me as profound. I don't have a solution, but I would advocate:

- More equal financial resources so that at least poor communities are not knocked out of the game by lack of cash.

- Culturally sensitive efforts to spread the word that organized educational opportunities pay off for all kids, everywhere.

- Changes in federal and state policy to support the arts and other "extracurricular" activities.

- Attention to the civic and organizational skills that it takes to pull together coherent educational programs that reflect the local culture

Posted by peterlevine at 9:44 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

December 12, 2008

a game for teaching civics

(Tampa, FL) I have come down here to begin training high school teachers to use a new software package that we call "The Legislative Aide Game." Students in social studies classes here will log onto a web site that treats them as interns in a fictitious Tampa-area legislator's office. They will put a real biography on the legislator's web page and start to receive emails with assignments from the legislator's staff. These assignments will ask them to study an issue in the real community of Tampa. They will do some initial reading and web research, and then they will start using the same software that we have implemented with college students in Boston. They will generate network maps of people, organizations, and issues relevant to their overall topic. They will interview the people they have put on the map and store the information they learn in nodes. The map will help them to identify "levers"--people, organizations, and networks that are in a position to make a difference on the assigned issue. The students will conclude by writing and presenting an action plan that takes advantage of the "change levers" of the community. Although they don't have to perform a service or action project in the real world to complete our curriculum, that would be a natural next step.

The teachers I met with this afternoon seemed fairly excited about the project, which will begin in January.

Posted by peterlevine at 6:50 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

December 11, 2008

"service" and exploitation

I can't go into details yet about our data or methods, but we have been talking to inner-city youth about civic and political engagement. I'm forming the hypothesis that when young, working-class and poor Americans hear about "volunteering," "community service," or "giving back to the community," they think of manual labor for no pay. The example that comes up most often is cleaning a street or park. These are precisely the jobs that people in their families and neighborhoods are paid to do (but not paid enough). Nor are such workers treated respectfully by their clients or supervisors; nor do they get opportunities for learning or leadership on the job.

The young adults we talked to attended high schools in which "service-learning" was mandatory. Often in such cases, the students end up cleaning or painting public facilities, under the direction of middle-class adults (teachers and others). So while Mom is cleaning hotel rooms for minimum wage and no benefits, her children may be cleaning parks as part of their education for democracy.

I can hardly think of anything more alienating than to be told that you are now going to study democracy and community, that you will learn habits that you should stick with for the rest of your life, that the way you're going to study citizenship is to perform low-skilled manual labor, and that no one is going to pay you for that work.

I am proud to be part of the movement for community service and service-learning. I think these opportunities should be expanded. But the first rule is, Do no harm. If done poorly in the context of working-class life, I think service-learning could be one of the most effective and lasting way schools have to disempower their youth.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:36 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

December 10, 2008

that narrow curriculum: it's not all about NCLB

Some time ago, we received a Ford Foundation grant to document the problem that almost everyone decried: because of the testing requirements in the No Child Left Behind Act (the comprehensive federal law related to pre-college education), schools were focusing on math and reading to the exclusion of social studies, art, music, physical education, and extracurriculars. All the data that supposedly demonstrated this problem came from current surveys of educational administrators or citizens, who were asked to say whether they believed curricula had narrowed since the passage of NCLB. They said yes.

We set out to provide supportive evidence by examining historical data about what teachers actually teach and kids actually study (based on contemporaneous surveys of students and teachers). What we found was much more complex and nuanced than our original hypothesis. Instead of "documenting" a problem, we showed that it didn't exist in the way we had expected.

We set out to provide supportive evidence by examining historical data about what teachers actually teach and kids actually study (based on contemporaneous surveys of students and teachers). What we found was much more complex and nuanced than our original hypothesis. Instead of "documenting" a problem, we showed that it didn't exist in the way we had expected.

- Transcripts show that high school students are studying more diverse subjects. Narrowing is not a problem at the high school level.

- There is no evidence of curricular change in middle school in the last decade.

- There has been some narrowing in elementary school, but mostly at first grade. Moreover, the narrowing trend began before NCLB and affects private schools just as much as public schools. Thus the cause is probably not NCLB but rather a combination of parents' and teachers' priorities, textbooks, state laws, local policies, etc.

- We had expected that new teachers would be most likely to focus on reading and math, because they have entered the profession under NCLB. In fact, more experienced teachers offer a narrower curriculum; new teachers are more likely to offer arts and social studies.

I personally believe that the narrowing of the curriculum in the early grades is a significant problem. But it cannot be solved by lifting testing provisions in NCLB. It's a much broader and more complex issue.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:14 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

December 9, 2008

turning "friends" into supporters

In our Boston-area social networking project and related work, we hear repeatedly that the challenge is to convert online connections into "real world" action. Young people are heavy users of online tools like MySpace and Facebook, but they are also quick to criticize these tools for being too easy and superficial and not necessarily changing the world. Allison Fine is producing a series of podcast interviews on the topic. Her first guests are Jonathan Colman of the Nature Conservancy and Carie Lewis of the Humane Society of the United States, both of whom are using Facebook's "Causes" application effectively. Download the MP3 podcast or check out the site for the series.

Our own criteria of success include the number of students who conduct service or activism as a result of using our social-networking tools, the number of organizations they serve, and the demographic diversity of their networks. We won't succeed unless they go offline.

Posted by peterlevine at 2:53 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

December 8, 2008

Clay Pit Pond

Focus first on the black trunks, then the snowthat beats the ripples, then the wind-whipped flag,

the high school's streaked cement and darkened glass,

like the building I would have trudged up to

twenty-five winters past. He tugs to move,

snuffling his first snow; everything's a first

for him--hunched ducks on logs, the distant train.

In my ears, Albinoni's oboes step

lightly, unruffled by the imminent

coda, and take the repeat serenely,

even though poor old Tomasso's been dead

(of diabetes) more than two hundred

sodden Venetian winters. The coda comes,

the dog pulls me homeward, and where we'd stood,

the patient snow melts back into the waves.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:30 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

December 4, 2008

on Black dentists, and paths to prosperity

A few weeks ago, in a hotel room, I watched Chris Rock's current show--which is very funny. One segment concerns his suburban New Jersey neighborhood, where the houses cost millions. He notes that there are only three other African Americans in town, and all are extremely famous and talented cultural figures. But his next-door neighbor, who is White, is a dentist. He says that for a Black dentist to reach this level of success, he'd have to discover a cure for cavities (or something to that effect).

I get the joke, but it sends the wrong message. I cannot find statistics on dentists' income by race/ethnicity. But I suspect that Black dentists make roughly the same as White dentists; and if there is a gap, it is partly explained by the greater willingness of Black dentists to serve African American communities. African American male physicians earn slightly more than White male physicians; Black women physicians earn less. (See this and this.)

I fully understand that the path to dental school can be much harder if you are an African American teenager than if you are White. On average, schools that enroll lots of Black kids score lower on tests and have weaker curricula; and African American youth often have fewer educational networks and resources at home. Further, there is evidence that once African American students reach dental school, there is "subtle discrimination and miscommunication." Only 5.4 percent of current dental students are African American (pdf).

Nevertheless, the main message has to be that there is a path to prosperity that runs through a high school diploma, a BA, and then a professional degree. While that path is hard, it is much easier than trying to be a world-famous actor or athlete. Dental school can get you to Summit, NJ; but Hollywood or the NBA probably cannot.

Posted by peterlevine at 4:23 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

the fierce urgency of a transition

(Framingham, MA) I am involved in several networks devoted to public goals, some of whose members have connections to the Obama transition. I'm getting urgent emails and phone calls with tense messages about the need to get our positions right, succinct, forceful, and in the hands of people closer to the President Elect than we are. Meanwhile, some 300,000 people have already submitted their resumes to the transition--compared to 44,000 resumes that were ever submitted to the Bush transition. These people want jobs, of course, but they are also idealists who see a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to advance their causes. If you have worked all your life on community banking, or wind power, or relations with Sierra Leone--to name completely random and hypothetical issues--it suddenly seems as if this is your one best chance to make a big difference at the national scale. So you are pounding out memos for the transition team, uploading your resume, calling people who know people who know Obama team-members.

It's all very important. There really is a window of opportunity that will begin to close in a few months. Those who advocate effectively will make more of a difference than those who do not. But somehow I think we all need to adjust to the reality that there are far more vital causes than there are opportunities to act in the first few months of a new administration; and there are far more talented activists than jobs. We need strategies that go beyond the first 100 days and that involve other branches of government and other institutions. As always, we need cool heads, broad coalitions, and careful deliberation.

And now, back to that urgent draft email to someone who knows someone in Chicago ...

Posted by peterlevine at 11:08 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

December 3, 2008

LA Peace Collaborative

(suburban Maryland): I'm here with a group of young leaders, mostly young people of color who work with youth on service projects, social justice efforts, and community organizing. At a previous meeting, a subgroup decided to focus on issues of violence--or, as they put it, the "peace piece." With characteristic energy and vision, they launched a practical project: a "Peace Jam" in Los Angeles.

Their idea is that violence emanates from Los Angeles because the global mass media, headquartered there, broadcasts images and stories of violent youth and gang culture to the whole world. The music, movie, and game industries essentially profit from local youth violence. My friends are organizing a youth peace culture right in the heart of LA. On September 7, they played a role in bringing Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Rigoberta Menchú Tum, and other Nobel Peace laureates to town to work with kids. Sign up, watch their videos, and give them money; they're great.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:14 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

December 2, 2008

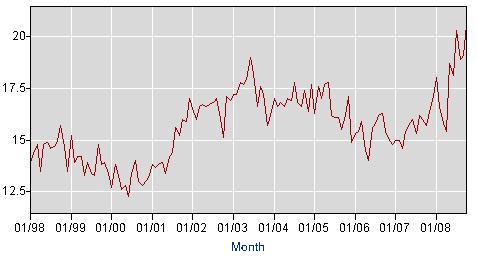

youth unemployment passes 20%

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the unemployment rate for ages 16-19 was over 20% in October. For ages 20 and older, the rate was 5.9%.

Youth unemployment, seasonally adjusted

Unemployed youth are not only missing income and benefits. They are also losing crucial opportunities to develop skills, networks, habits, and experience. The Kennedy-Hatch Serve America Act is certainly not the whole solution, but I think it should be passed quickly as an element of the economic recovery plan. It is an efficient way to give as many as 250,000 young people highly educational work experiences. They will also exemplify public work for Americans of all ages.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:09 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

December 1, 2008

truth is not power

(On the USAir Shuttle to DC) Mark Danner in the New York Review of Books:

- However cynically we look to our political past, it is there that we find our political Eden: Vietnam and its domestic denouement, Watergate—the climax of a different time of scandal that ended a war and brought down a president. In retrospect those events unfold with the clear logic of utopian dream. First, revelation: intrepid journalists exposing the gaudy, interlocking crimes of the Nixon administration. Then, investigation: not just by the press—for that was but precursor, the necessary condition—but by Congress and the courts. Investigation, that is, by the polity, working through its institutions to construct a story of grim truth that citizens can in common accept. And finally expiation: the handing down of sentences, the politicians in shackles led off to jail, the orgy of public repentance.

But today, Danner writes, scandals have no repercussions. Powerful people are "exposed" doing bad things and just keep on doing them. "Revelation of wrongdoing leads not to definitive investigation, punishment, and expiation but to more scandal. Permanent scandal. Frozen scandal."

The present situation is the typical one, I believe, and the Watergate era was an exception. In general, information is not a form of power. Information and analysis are essential conditions of good political action, but they do not cause things to happen. We expect far too much from disclosure and transparency, when we actually need motivated, skilled, and organized citizens. The important truths are already clear enough; we need ways of acting on them.

There is a great old American tradition of believing that publicizing and exposing once-secret facts will influence power. According to the historian Robert Wiebe, the Progressives of 1900-1924 believed that "the interests thrived on secrecy, the people on information. No word carried more progressive freight than 'publicity': expose the backroom deals in government, scrutinize the balance sheets of corporations, attend the public hearings on city services, study the effects of low wages on family life. Mayor Tom Johnson of Cleveland held public meetings to educate its citizens. Senator Robert LaFollette of Wisconsin heaped statistics on his constituents from the back of a campaign wagon. Once the public knew, it would act; knowledge produced solutions." Lewis Brandeis captured this theory in an aphorism: "Sunlight is the best disinfectant."

The edenic period to which Danner refers, the 1970s, saw a revival of these ideas. John Gardner, Ralph Nader, and their allies were heirs to Brandeis and La Follette. They won and used the Freedom of Information Act, sued corporations to force disclosure of their records, and barraged the media with statistics. Meanwhile, the New York Times fought the Pentagon in the Supreme Court, and Woodward and Bernstein interviewed Deep Throat in a parking garage. Thanks to their efforts, William Greider argued at the time, "information, not dirty money, is the vital core of the contemporary governing process." This idea could be raised to a very high principle. Dr. King had preached: "We shall overcome because there is something in this universe which justifies William Cullen Bryant in saying truth crushed to earth shall rise again."

A whole slew of liberal "public interest lobbies" arose, whose role was feed hitherto secret information to the public through the nonpartisan and professional press. David Vogel writes that in the early 1970's, nearly 100,000 households gave "at least $70 a year to three or more of the following: Common Cause, Public Citizen, ACLU, public television and public radio, and environmental lobbying groups"--institutions that attempted to check power with data. Senator Abraham Ribikoff observed, "instead of the big lobbies of the major corporations dominating the hearings process, you have had practically every committee in Congress according 'equal time' to public interest people."

Today, I sense a revival of the Brandeis theory of power-through-transparency. It is a reaction to the indefensible secrecy-mania of the Bush years, and it embraces the Internet as a powerful new tool for disclosure. But the previous waves of transparency proved disappointing, and we should bear their lessons in mind.

First of all, more information is not better. Torrents of information can be overwhelming. For instance, what are we supposed to do with the names, addresses, and employers of the millions of people who made political contributions in the 2008 election? We can sort and analyze the data and look for patterns. I helped with that kind of analysis when I worked for Common Cause, and it can be done even more effectively today with new software tools. Hundreds or thousands of meaningful patterns can be found in campaign records. Tens of thousands of people can collaborate in this analysis. They will add little to the obvious truth that politicians take lots of money from individuals with interests before the government, and the same interests typically prevail.

Second, facts and values are not starkly and cleanly separated. All policy debates involve differences in values as well as complex factual premises and causal theories--each involving much uncertainty. In periods of broad ideological consensus, facts become powerful tools in debates. For instance, if all our leaders are Keynsians who expect the government to intervene in certain ways in the economy, facts about incompetence or malfeasance become influential. But if our leaders hold profoundly different views about the proper economic role of government, facts matter much less. They become debating points, and every side can cite its own.

I am not an epistemological skeptic. There are truths and there are falsehoods. But there is also much uncertainty and complexity in the world. If the political culture expects information, everyone will start producing information to support their views, and fundamental truths will (if anything) look more elusive. After the open government reforms of 1972-1976, David Vogel writes, "It took business about seven years to rediscover how to win in Washington." Corporate America appropriated the tactics of the public interest movement, including the "sponsorship of research studies to influence elite opinion, the attention to the media a way of changing public attitudes, the development of techniques of grassroots organizing to mobilize supporters in congressional districts, and the use of ad hoc coalitions to maximize political influence." Some of what business argued was valid. Some was partial or downright false. Regardless, the impact of the public-interest groups declined precipitously, because each of their press releases and studies was now met with a counter-barrage of facts and claims from the other side.

As a political strategy, "exposure" requires organized and motivated organizations that can be trusted to take action in response to problems. Such institutions are weaker today than they were in the mid-20th century. There are many reasons for their decline, but growing transparency certainly didn't help them. In the liberal era of 1940-1960, workers had considerable influence, because the Democratic Party, labor unions, and liberal media were powerful. Rank-and-file constituents of these huge organizations trusted their leaders to tell them how to vote and when to strike. Although this trust could be misplaced, it was often salutary. To acquire political information is difficult, time-consuming, and expensive, so most people don't participate at all unless they are guided by trusted institutions that embody their core values. One set of institutions, political parties, suffered when the campaign-reform and civil-service bills of the early 1970s struck at their main sources of power: fundraising and patronage. The press lost public trust for a whole variety of reasons, including poor media ethics. But I think part of the reason was growing transparency. Readers knew more and became more skeptical about reporters' and editors' motives, and as a result the impact of any given newspaper shrank.

Meanwhile, unions lost members rapidly as a result of mechanization, foreign competition, and weak labor laws. Workers and middle-class consumers did gain the support of lobbies such as Common Cause and Public Citizen, but these groups had far less power than the old party structures had. In 1994, just 2.8 percent of the population said that they were members of "some group like the League of Women Voters, or some other group which is interested in better government." By contrast, almost one third of nonagricultural workers had belonged to unions in 1953, and 47 percent of voting-age Americans had identified themselves as Democrats. The rise of organizations like Public Citizen could hardly compensate for a 50 percent drop in union membership or a 25 percent decline in support for the Democratic Party.

The moral of the story is not to expect that reforms will follow transparency, or that scandals will discipline the powerful. What we need most of all is organization; there is no substitute for it. I am open to the idea that online organizing can complement or even possibly replace offline organizing. But online organization does not equal websites with information, or even computer-based discussions. It means networks of people who are able to get each other to act.

[Note: portions of this post are adapted from my 1999 book, The New Progressive Era, chapter four.]

Posted by peterlevine at 9:44 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack