« October 2008 | Main | December 2008 »

November 27, 2008

Happy Thanksgiving

(Madison, WI): I am swearing off this blog for Thanksgiving Day and the day after, as I have every year since 2003. I am thankful for many things, including the opportunity to write on this space. Back on Monday.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:23 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 26, 2008

citizens in the economic recovery plan

On Monday, I made a general argument for putting citizens to work (as citizens) on public problems. I had previously argued that this approach would change the relationship between citizens and government from the dysfunctional relationship under George W. Bush and from the relationship of the Clinton years, when government was presented as a helper to relatively passive individuals.

It's worth thinking about this philosophical shift in relation to our most urgent immediate problem: economic recovery. The Bush bailout and stimulus efforts have involved almost no accountability or transparency. The money has not been directed to ordinary Americans or used for important public purposes. We can do much better by combining Barack Obama’s call for "service and active citizenship" with his economic recovery plan.

In policy terms, putting citizens to work on economic recovery means:

- Passing and fully funding the Kennedy-Hatch Serve America Act (which Senator Obama cosponsored) as a contribution to the economic recovery

- Enlisting citizens to provide guidance and accountability when public money is used for the economic recovery. Tools for participation can include:

- Public deliberations at the local level about priorities for spending

- Citizens’ review panels that complement (not replace) professional oversight by government auditors

- Web-based tools to disclose details about spending and invite public discussion and input

- Civil servants supporting such work by citizens as part of their job descriptions

- Creating jobs programs within various agencies and policy domains that involve the participants in planning and learning. HUD already funds YouthBuild to construct houses and teach civic skills. This is a model for other agencies.

- Civil service reform to make public sector jobs more attractive to younger people and to promote partnerships between agencies and non-governmental groups.

- A renewed focus on civic education in k-12 schools, colleges, and youth employment programs, so that young people learn how to discuss and analyze public problems as part of their preparation for the work world.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:31 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

November 25, 2008

mapping Boston's civil society

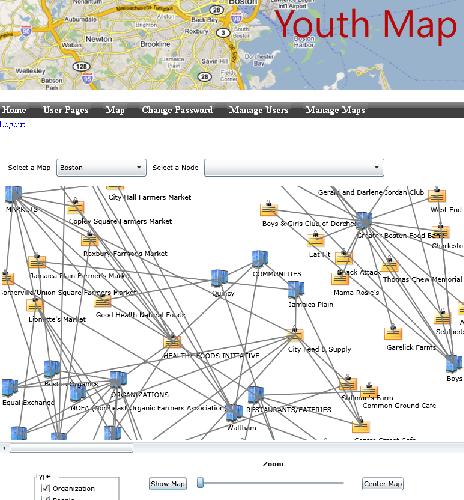

We're busy mapping Boston. Students place nodes that represent people, ideas, or organizations on a blank plane. Each node stores data, such as contact information, goals, activities, and geographical locations. Connections among nodes represent real collaborations. The data can be shown in lots of ways--on a geospatial map, as a network diagram with various center-points, as a list of search results. Ultimately, this software will be an application for Facebook and MySpace, making it easy for people to add or use data . For now, we have a standalone website.

Here's a screenshot from today. This represents the work of just a few Tufts undergrads over a couple of weeks. We're already working with students at UMass Boston and will be expanding beyond those campuses in the spring. The software is also capable of automatically harvesting organizations and links from the Web and pasting them here to be analyzed by human beings.

Purposes:

- Recruiting people and organizations. One can search for individuals who are connected, even indirectly, to a given issue and then ask them to participate in events or projects.

- Finding opportunities. One can search for places to volunteer, give money, or organize politically. The search can be by key-word. More interesting is to search for organizations that are linked to other organizations.

- Analysis and deliberation. One can link two issues together, or link an issue to an organization, and then debate the connection. Is homelessness worsened by zoning? That hypothetical connection can be discussed on the map itself.

- Broadening sources. Journalists, government agencies, foundations, and researchers tend to ask the same people for information and opinions. They often rely on formal credentials as evidence of knowledge. The network map can lead them to overlooked citizens who are useful sources because of the social roles they play.

- Investigations. One can look for inappropriate or problematic connections, or lack of connections.

Issues that students have brought up so far:

- Privacy: Whose information should go on the map, and who decides that?

- Chilling effects: Would people be discouraged from linking to controversial organizations and causes if their links could be mapped?

- Spam and other bad stuff: Inappropriate content can be added to the map

- Marketing: Instead of recruiting volunteers or activists for a social cause, a company could use the map to find influential customers.

- Sustainability: It's fun for me and my colleagues to build the map. But other people who contribute need to know that it will still be there (and kept current) in five years.

- Limits: This is a Boston area map. That geographical definition gives it useful density. But Darfur could belong on the map, since Boston-area students work on Darfur. Former Bostonians could place themselves on the map. Is there any point to a geographical limit?

Posted by peterlevine at 12:01 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

November 23, 2008

work, not service

Candidate Barack Obama, July 2:

- "I will ask for your service and your active citizenship when I am President of the United States. This will not be a call issued in one speech or one program—this will be a central cause of my presidency."

President Elect Barack Obama, Nov. 22:

"We'll put people back to work rebuilding our crumbling roads and bridges, modernizing schools that are failing our children, and building wind farms and solar panels; fuel-efficient cars and the alternative energy technologies that can free us from our dependence on foreign oil and keep our economy competitive in the years ahead."

These two statements seemed to be about different topics. The first was an argument for increasing the number of federally-funded civilian "service" slots to as many as 250,000; the second announced a plan to create or save 2.5 million full-time jobs, mostly in the private sector. The first makes us think of unpaid volunteering or short-term, low-paid positions in nonprofits and government agencies. The second conjures images of permanent, salaried employees in labs or on corporate assembly lines. "Service" is about personal values: patriotism, civic virtue, caring, or helping--a "thousand points of light." Job programs are about macroeconomic growth and take-home pay for hard-working Americans.

I think the two ideas should be combined, and "work," not "service," should be the hallmark of "active citizenship" in the Obama Administration. I have never been very enthusiastic about service on its own. It is marginal--a lower priority than one's job or family, something to do after work, on special occasions, or during adolescence or retirement. People involved in service tend to be congratulated and thanked regardless of their impact, whereas workers are expected to get the job done. Service makes the recipients look weak and needy, whereas work is an exchange for mutual benefit.

Service programs, such as Americorps, can certainly be great for the volunteers and the community. But that is because they provide work, albeit with a strong and commendable element of civic education for the workers. Meanwhile, a full-time, paid job in the private sector can also be "active citizenship," if we allow, support, and encourage the employees to work on public problems (such as modernizing schools or building wind farms).

As I wrote here recently, the Obama Administration can restore a New Deal version of liberalism whose central task is to put people to work for the public good. Private sector jobs are part of that, especially if federal subsidies, incentives, or mandates steer these jobs toward public purposes. Public sector careers at every level, military service, and civilian service programs such as Americorps are also important. So is an educational system that prepares people for public work. Students will need a strong dose of civic education so that they can discuss and define the public problems that they choose to address as workers. It is not enough to prepare them for an increasingly competitive job market; they also need to shape that market for public purposes.

I would admire this form of liberalism at any time, because of its ethical conception of the citizen as an active, creative agent. But today seems an especially appropriate moment to bring back the New Deal conception. We need jobs programs for standard economic reasons; and our newly elected president has pledged to make "active citizenship ... a central cause."

Posted by peterlevine at 12:52 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 21, 2008

losing one's past

- "The cradle rocks above an abyss, and common sense tells us that our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness. Although the two are identical twins, man, as a rule, views the prenatal abyss with more calm than the one he is heading for (at some forty-five hundred heartbeats an hour). I know, however, of a young chronophobiac who experienced something like panic when looking for the first time at homemade movies that had been taken a few weeks before his birth. He saw a world that was practically unchanged--the same house, the same people--and then realized that he did not exist there at all and that nobody mourned his absence." -- Vladimir Nabokov, Speak, Memory

I have a different problem. I feel my past shifting from personal memory into objective history and thereby ceasing to be fully mine.

When I was a little boy, the 1940s seemed an entirely different epoch. It was the lost world of my parents' youth, of FDR on the radio, genocide, jazz, Marines on Iwo Jima. It was black-and-white, sad, and dignified. But now the decade of my childhood, the 1970s, is closer to the Roosevelt Administration than it is to the present.

I presume that when I walked down the streets of London or Syracuse, NY, holding a parent's hand, I did not especially notice the wide lapels, mutton-chop sideburns, punk graffiti, decaying American downtowns, and leftover Blitz bomb-sites that characterized that era. I probably focused on the perennials of childhood: cracks in the sidewalk, low walls for walking on, crunchy leaves or splashy puddles, food smells and parents' voices. But now I can remember hardly anything from a first-person perspective. Instead, I see myself from the outside, a representative of the period, shot in lurid Kodachrome like a used album cover. The image is historical, long-gone, much more like the newsreel footage of 1945 than the real world of today.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:01 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 20, 2008

how to keep them engaged

I am pleased that this year's election has prompted a lot of thinking about how to keep young people engaged. "Beyond the Vote" was the theme of the National Conference on Citizenship. There have been good news articles on the topic, e.g., this one in the Atlanta Journal Constitution. And now The American Prospect has asked a bunch of experts, plus me, to opine on what the Obama Administration should do to keep young people excited. Here are all the suggestions. Mine is this:

- Barack Obama won an unprecedented 66 percent of the under-30 vote. Ronald Reagan set the previous record with 59 percent in 1984. The Reagan cohort has remained conservative ever since. Obama now has an opportunity to achieve a lasting realignment.

On the campaign trail, he electrified youth by asking them to work on public problems: "I will ask for your service and your active citizenship when I am president of the United States. This will not be a call issued in one speech or program; this will be a cause of my presidency."

"Active citizenship" means more than helping the needy (which defined the liberalism of the Clinton era). It means talking with diverse people about challenges, analyzing and debating, and then working together to solve problems. Youth are hungry for this kind of work.

During the campaign, Obama gave youth many ways to plug in, from "friending" him on Facebook to taking a semester off to organize. Now that the election is over, he needs to offer a similar range of opportunities to cement their engagement. An issue like climate change requires a full spectrum of participation, from pledging not to drive once a week, to advocating legislation, to weatherizing homes as an Americorps volunteer, to becoming an EPA scientist. At a time when jobs are scarce and the public sector is weak and archaic, citizens' work should be the hallmark. Then, there will be Obama Democrats in 2060 the way there are New Deal Democrats today.

I'm actually doing some fairly serious, data-driven research on generations' roles in political realignments. It's interesting stuff but I'm far from being able to report anything here.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:02 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 19, 2008

summing up CIRCLE

(Des Moines) After meetings this morning, I'll be on airplanes almost all day. No time to post anything substantive, but there's a nice feature article about CIRCLE on the Tufts University home page right now.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:22 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 17, 2008

service learning shrinks

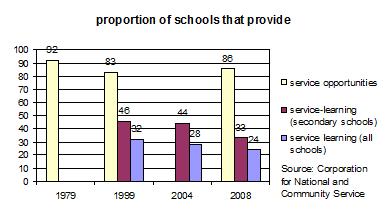

(Des Moines, IA) I'm here to talk to teachers, students, and nonprofit leaders about service-learning: the intentional combination of community service with academic work. This is a big deal--24% of schools offer it. But the prevalence has declined, according to a new study by the Corporation for National and Community Service--down from 32 percent in 1999.

It's my sense that the movement for service-learning has reached a crisis point. It isn't included in federal education law; it isn't a priority in an era of concern about reading and math; the federal funding has been cut (in real terms) since 2001; and the quality of programs is so uneven that outsiders could be reasonably skeptical about its value. On the other hand, the best programs are superb; they fit the outlook of the incoming administration; and there is strong support for service-learning in the Kennedy-Hatch Serve-America bill that both Senators McCain and Obama promised to sign. That bill would direct most resources to poor districts, which today are much less likely to offer service-learning. So we could be poised for improvements in quality, quantity, and eqaulity. Or else service-learning could falter if Kennedy-Hatch isn't fully funded and the grassroots movement continues to shrink.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:47 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

a moment for inclusion

Wherever I go these days (the State Capitol of Texas, a restaurant in Boston's Chinatown, and many points in between), people are telling moving stories about the reaction to the election. For instance:

- Three hundred people were still lined up to vote at a precinct in Pittsburgh when time ran out. Very quickly the news came that Obama had won Pennsylvania. So there was no opportunity to vote, and voting didn't matter because the state had been called. Everyone decided to stay in the parking lot and pray together for the outcome in the West.

- Much of the Tufts student body was gathered in the Student Center when news came of the Obama victory. They massed in the main quad and sang the National Anthem and other patriotic songs until 1 am, when they marched to Davis Square.

When both of these stories were told, there were Republicans in the room who listened with grace and even appreciation. I think the President Elect has broad good will, partly because he broke the race barrier, partly because he ran a dignified and positive campaign, and partly because we all need him to succeed in this time of crisis. But it's important to remember that many people did not vote for him, and some certainly had principled reasons not to. We need a two-party system across the country, including here in New England where there are now zero Republican US Representatives. Nothing really valuable can happen unless people of good will on the Republican side voluntarily participate, both in Congress and in civil society. It's asking a lot for them to keep clapping at stories of Democratic triumph. They can focus on the civil-rights breakthrough, as William Bennett did rather gracefully on Election Night. But there is much more to Obama than his African American heritage. Especially for those of us who enthusiastically supported him because of his agenda, an important challenge now is to make sure we respect differences and are ready to include other people without assuming that they buy the whole package.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:27 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 14, 2008

the Stoics were right

(Austin, TX) Last night, in Worcester, Mass., I heard Michael Dukakis speak at Clark University. He was very funny and had a whole ordinary-old-guy-who-once-lost-a-presidential-election schtick going. "Folks, I owe you an apology. If I had beaten Old Man Bush, you'da never heard of the kid. ... Folks, you can ask me any questions you want, but not about the campaign we just had. If I knew anything about presidential politics, I'd be standing here in a different capacity." "Folks, next time I run for president, Jim and Bob here are going to be my national co-chairs."

I happened to walk out with the Governor, Kitty Dukakis, and a family friend of theirs, although I didn't bug them by saying anything. The former Democratic presidential nominee went off to find the family car and save his elderly companions from walking on the rain-slicked paths.

Meanwhile, we read that the Obamas' ordinary lives are now over--no more dinners out for Barack and Michelle, unless they want to have 300 Secret Service agents along. No more hair cuts at barber shops. It makes me think of the fickleness of fame, that great wheel that lifts some up and lowers others. Although the Obama Campaign was far more impressive than the Dukakis Campaign of '88, I'm convinced that Obama won and Dukakis lost because of timing and sync with the national Zeitgeist. In the affairs of individuals, chance is almost everything. "The wise man pays just enough attention to fame to avoid being despised"--Epicurus.

Posted by peterlevine at 5:43 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 13, 2008

illumination from the charter debate

(On the train to Worcester, MA) I am going to Clark University to join Jeffrey Henig on a panel about his new book, Spin Cycle: How Research is Used in Policy Debates: The Case of Charter Schools. I found this great book in the section of the library devoted to charter schools and vouchers. It does include a helpful and nuanced summary of the current research on charter schools. But it had much broader implications. It's really about the ways that social science, the mass media, advocacy groups, and democratic institutions interrelate in our era.

Charter schools provide a fascinating case, because the debate about them has been passionate and ideologically polarized. It has played out in think tanks, Congress, and the front pages of national newspapers. But it did not have to develop that way. Charter schools could have been seen as a modest way of tweaking management systems in public education. There are many old public schools (Boston Latin, Stuyvesant) that essentially operate with their own charters or special exemptions. There has always been a continuum between centralized control and autonomy within public school systems. Several European social democracies--usually, and rightly, seen as left of the United States--manage schools in ways that resemble our charters more than our unified systems. So chartering could have been introduced without a lot of fanfare, without especially high expectations, and not as a test of larger social theories.

Instead, charters were promoted as experiments with several grand political theories. Conservative foundations and intellectuals favored them as tests of the market-choice hypothesis. If conservatives were right that government monopolies guarantees poor results, then charters (which increased choice) should perform better than regular schools. A successful experiment with charters would open the door to competition and deregulation across education and other sectors, including postal services and national parks.

But conservatives were not the only proponents of charter schools. One of their intellectual parents was the union leader Alebert Shanker, whose vision could be described as professionalism for teachers. His idea was that teachers should form their own charter schools, thus becoming more like white-collar professionals and less like bureaucratic pawns. There were also moderate Democrats who saw charters as a way of fending off vouchers. They hoped that success with charters would blunt demands for real privatization.

Under these circumstances, everybody seemed to want and expect the "killer study" that would vindicate or repudiate the charter model. Certain preliminary studies did get massive attention, especially a study by the American Federation of Teachers that appeared on page 1 of the New York Times. Each significant study was scrutinized for ideological bias and denounced by opponents. The coverage of each study was also subjected to intense scrutiny for bias. Some observers threw up their hands, concluding that education research was just a food fight that offered no illumination.

The model that Jeff Henig offers as an alternative is research as cumulative, incremental, and pragmatic. While unions and conservative think tanks exchanged studies and accusations, a much subtler and more nuanced literature was developing that found--as one might expect--a range of effects by different charters on various outcomes for various student populations. That range was itself a refutation of the very simple libertarian theory that any extra degree of parential choice will cause huge improvements in all outcomes. But no one should have expected a simple and universal causal theory in such a complex area as education. The emerging research is policy-relevant. It doesn't support either a massive expansion or a termination of the charter experiment, but various tweaks and reforms to improve quality.

Henig recommends, among other points, that the federal government should concentrate on collecting excellent public data for scholars to dissect, and that scholars should be rewarded for painstaking, cumulative research and not pressed to be overly "timely" or "relevant." I am a proponent of the Engaged University idea, but I actually admire careful, low-profile engagement in communities much more than participation in the "Spin Cycle." So I can endorse Henig's recommendations. I also support his call to push the charter debate back down to the local level, where it is typically less ideological and more pragmatic.

I will, however, put in a word for ideology. We citizens cannot assess the pros and cons of each policy tweak. Yet we should be involved in setting policy. One powerful shortcut is to think in ideological terms, as long as one is alert to complications and exceptions and open to serious reevaluation. I, for instance, know very little about environmental issues. But I must vote and make consumer choices. I could try to master all the science and social science on the issue, but that's quite unrealistic. Instead, I go through life with some ideological presumptions--generally friendly to science and to regulation when it seems to be informed by science; generally skeptical of big business. But I pride myself on being alert to contradictions.

If that's how most people should think about education, then it seems fairly natural and maybe even desirable for ideological groups to promote their views in public debate. They will and probably should seize on examples like charter schools to make their points. There are definitely costs: simplification and polarization. But there are also advantages. It's possible that when the dust finally settles on the charter-school debate, we will have learned something.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:53 AM | Comments (3) | TrackBack

November 12, 2008

Michael Chabon on Peace Now

I loved Michael Chabon's Yiddish Policeman's Union and took it as an exploration of rosy nostalgia and distopian fantasy as two poles of modern Jewish thought. Then into my mailbox comes a letter from Ayelet Waldman and Michael Chabon himself, on behalf of Peace Now. They write:

- In imagining a vibrant but endangered Yiddish-speaking homeland for the Jews in an alternate-history Alaska, Michael's novel The Yiddish Policemen's Union draws freely on both of these Jewish imaginative traditions, these differing modes, making a kind of funhouse-mirror prediction about a Jewish future. But there is another powerful strand in the Jewish way of thinking about the world and our place in it, a kind of imagination that focuses neither on the past with its glories and disasters nor on the future, whether shining or dark. It is the tradition embodied in the final word of the organization on whose behalf we are writing you today: it is the tradition that embraces, and devotes itself, to the imperatives of the now.

What has to happen now, as they argue, is for the State of Israel to negotiate a two-state solution with the Palestinian Authority. That requires putting aside both fundamentalist nostalgia and paralyzing fear. Israel can only have a decent present and future if it addresses the Settlements issue and negotiates permanent borders.

Posted by peterlevine at 3:48 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

November 11, 2008

my favorite article on the 2008 campaign

That would be Mark Danner's "Obama & Sweet Potato Pie" in the New York Review of Books. Danner describes two rallies, one for Obama and one for McCain. As he notes, the national press corps follows the candidates, listens to them repeat their stump speeches time after time, and reports only the new lines that are inserted daily for their interest--usually attacks on the other candidates or responses to attacks. I well remember seeing Bill Bradley speak live in the 1992 campaign and marveling that the only aspect of his speech that appeared in the newspaper the next day was a line about Bill Clinton. The whole thing is a game that the campaigns and the press know how to play.

But a campaign also consists of whole speeches delivered in real settings to people from geographical communities. Danner depicts two such occasions as the dynamic interplay between the candidates and their audiences. He does an unusually good job of portraying both sets of voters with understanding and sympathy. He suppresses his own judgments in the interest of clear-eyed reporting. For me, the piece pretty much sums up the whole campaign.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:59 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 10, 2008

first steps with a Boston-area social network

We have a fairly large grant from the Corporation for National and Community Service to build a new kind of social network for college students in the Boston area, to support their community research, volunteering, recruitment, and advocacy. At the heart of it is software for "mapping" the networks that exist in a community. This software will soon be plugged into major social networking sites such as Facebook and MySpace, so that students will find it where they are and will not have to visit a standalone site. Meanwhile, some Tufts undergrads have started to use the not-so-user-friendly standalone version. As part of a commitment to openness and public citizenship, their work is going online from the beginning. And here's a little screenshot from their emerging network map.

Posted by peterlevine at 3:33 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 7, 2008

rules for organizers

(On the USAir Shuttle back to Boston)

10. Never provoke conflict to prove one's strength or importance or to guard one's turf.

9. Hold no grudges.

8. Never resent or complain about not being invited to a meeting, but try to attend meetings to which one is invited.

7. Minimize one's use of air time in conversations and meetings.

6. Conserve scare resources, such as grants, that others could use if you didn't have them. Minimize all forms of overhead.

5. Evaluate the effectiveness of organizations but commit to people even if they are not always effective.

4. Don't gossip; celebrate other people's work.

3. Charitably interpret other people's positions and treat differences of opinion as assets.

2. Use every opportunity to help other people develop skills and reputation.

1. Care about whole people, not just about their opinions or their work.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:47 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 6, 2008

the core principle of a presidential administration

(On the USAir Shuttle to DC) I think the most important question about presidential candidates is not what kind of people they seem to be or what they promise to do if elected, but rather how they view the relationship between individuals and the government. Their characters are hard to assess from afar and will change in office; their policy proposals will also shift. But poor presidents always have vague, incoherent, or downright bad ideas about how citizens and the government should relate. Great presidents are elected with compelling new visions of this relationship, and they make those visions real.

Ronald Reagan's core idea was that the valuable aspects of life were private and voluntary. The most salient fact about the government was that it compelled people to pay for it. So compulsion was at the heart of the relationship. Soldiers and police officers had moral standing because they put their lives at risk to protect the American private sphere. Their use of force and tax money was therefore legitimate. Otherwise, "government is not the solution to our problem[s]; government is the problem."

Bill Clinton beat George H.W. Bush on the platform that government should help people who were suffering economically. So helping was central to the relationship. As Clinton said in his 1992 acceptance speech, "We have got to ... give our people the kind of government they deserve, a government that works for them. A President, a president, ought to be a powerful force for progress." Government could best help if it were efficiently and skillfully managed. Clinton was a generally successful manager and employed a lot of smart people to help Americans lead safer and more prosperous private lives. He also created new ways for citizens to engage--through AmeriCorps--but the work volunteers were called to do was almost always "service" in the sense of helping the unfortunate.

For Jimmy Carter, in the aftermath of Watergate and Vietnam, the salient aspect of the relationship between citizens and the government was trust. Trust had been violated; Carter promised to restore it by acting honorably in the White House. "I will never lie to you" was his signature campaign line.

For FDR, I think an essential aspect of the relationship was work. People were literally without work in 1932, and FDR offered to hire many of them. From the WPA and CCC to the US Military in World War II, the New Deal was government-as-employer. Even those Americans who were never paid by the government (the vast majority, of course) were supposed to work on public problems. That was the New Deal ideal.

Barack Obama launched his campaign by addressing citizens' relationship with government and he never stopped talking about it. It even came up in his 30-minute TV ad. I thought this theme was under-reported, even though it is always the most important question about a presidential candidate, and Obama has a distinctive view.

Obama's core idea is that citizens are at the center of politics. Not private individuals, not the government, not politicians, but people working together in public, on public matters. Campaigning in New Hampshire in 2006, he said, "There's a wonderful saying by Justice Louis Brandeis once, that the most important office in a democracy is the office of citizen. ... All of us have a stake in this government, all of us have responsibilities, all of us have to step up to the plate."

Obama broke away from the helping model that still guided Hilary Clinton and from the privatism that was the main theme of modern conservatism. On the campaign trail, he modeled his new conception in two important ways--by making his campaign maximally participatory (pushing power out to the network) and by lowering the partisan temperature a notch. He is a Democrat and he was willing to debate and compete with Republicans. But he never seemed to relish this difference. The reason is that citizens are both liberal and conservative, and they need to work together to solve any serious problems. Competition is appropriate in a campaign, but campaigning is a role for politicians, and they are not the heart of politics.

There is a good fit between Obama's vision and the New Deal, insofar as Roosevelt supported "public work" (in my friend Harry Boyte's phrase). That is why national and community service programs may play a role in today's financial crisis like the CCC and WPA in the early thirties. Obama talks more about listening and collaborating than Roosevelt did; FDR was a happy warrior on the campaign trail. But the country is different now. The Internet is the guiding metaphor instead of the factory floor. It will be fascinating to see what citizen-centered politics and public work mean in the Internet age.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:28 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 5, 2008

youth turnout estimates

It is proving unusually hard to tell how many Americans actually voted this year. The current count of votes is about 120 million, but there are clearly absentee and early ballots that remain to be counted. Estimates of how many still need to be tallied range as high as 13 million, although I personally have no idea. Our problem at CIRCLE is that we use the total vote count to calculate youth turnout. Usually, to be consistent, we use the vote count reported by the Associated Press at 6 am on the morning after the election. Using that number this year would suggest that turnout overall was not especially good. That's possible--conservatives may have sat this one out--but I am hearing reports that there are at least 3 million ballots in California alone that need to be counted.

As a result, we have delayed our usual day-after youth turnout estimate. Instead, we report a range. In essence, the low end of the range (which assumes that almost all votes have been counted) implies a small increase in youth turnout over the relatively high baseline set in 2004. The high end of the range takes youth voting close to a record level.

Regardless, it is clear that young people favored one candidate so strongly that they played a major role in his victory. Under-30s favored Obama over McCain by 66%-32%, an unprecedented tilt. The closest precedent is Ronald Reagan; he took 59% of the youth vote in 1984, and that generation remains conservative today. Another way to make the same point is to note that Obama actually lost the 45-and-older set. He won a decisive victory on the strength of under-30s.

Posted by peterlevine at 3:34 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 4, 2008

social media on election day

Stay tuned for CIRCLE's press releases regarding youth turnout--this evening and then early tomorrow morning.

Meanwhile, to get a polling location for yourself or someone else, text *pp* (polling place) and then the street address and zip to 69866.

To report conditions at your polling place (thanks to Archon Fung), visit the My Fair Elections Facebook page.

You can also report problems with voting via Twitter. Alison Fine says to use Twitter as follows:

- #[zip code] to indicate where you're voting; ex., "#12345"

#machine for machine problems; ex., "#machine broken, using prov. ballot"

#reg for registration troubles; ex., "#reg I wasn't on the rolls"

#wait:minutes for long lines; ex., "#wait:120 and I'm coming back later"

#good or #bad to give a quick sense of your overall experience

#EP+your state if you have a serious problem and need help from the Election Protection coalition; ex., #EPOH

Or use a cell phone:

Send a text message to 66937 that begins with "#votereport"

Key in a report by calling (567) 258-VOTE/8683

Posted by peterlevine at 10:06 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 3, 2008

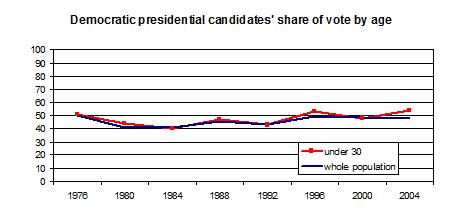

an unprecedented age gap

In elections since 1976,* young people (ages 18-29) have voted slightly more Democratic than the population as a whole. The average difference between the preference of under-30s and the national popular vote has been a mere 1.8 points. In 1984 and 2000,** the Democratic presidential candidate performed just slightly worse among young people than in the whole population.

But a recent Gallup poll of the 2008 campaign found Obama leading McCain by 62% to 34% among youth. In the same survey, Obama did not surpass 50% in any of the older age groups. If these numbers hold up, there will be an unprecedented age gap in voter preferences. No wonder there is such enormous interest in the youth vote story. For us at CIRCLE, it's always about democratic participation and youth voice. But this year, it's also about who wins the White House.

*I believe the 1972 exit poll did not disclose age. Before 1972, the voting age was 21.

**In 2000, Gore beat Bush among young voters, 48%-46%, but Nader drew 5% of young people.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:01 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack