« April 2007 | Main | June 2007 »

May 31, 2007

a typology of democracy and citizenship

I've been in Chicago for an interesting research conference on civic participation. There was some discussion about how empirical research should relate to "normative" thinking, i.e., arguments about how citizens ought to act, or how institutions should treat citizens. One of my colleagues* suggested that it might be helpful to provide empirical researchers with a menu of reasonable normative ideals, each of which might support different policies and outcome measures.

I'd first note that many people care about politics because they have substantive goals: for instance, social justice, individual liberty, moral reform, or concern for nature. Thus we could begin by listing substantive political ideals. But that would produce a huge array, especially once we cross-referenced each substantive goal with various ideas about appropriate political behavior. (For instance, you can be an environmentalist who believes in public deliberation, an environmentalist revolutionary, or an environmentalist who thinks that consumers and conservationists should bargain with business interests.) Thus I'd begin by conceding that there will be debates about what makes a good (or better) society. Assuming that the people engaged in these debates want to handle their differences democratically, we can turn to various rival views of democracy:

1. Theories of democratic participation

a. Equal influence in an adversarial system: The main purpose of politics is to bend institutions to one's own purposes, nonviolently. As in the title of Harold Lasswell's 1958 book, politics is "Who Gets What, When, How." It is desirable that poor and marginalized people participate in politics effectively, because this is their way to counter massive inequality in the economy. Voting is a core measure of participation; votes should be numerous, and the poor should be at least as prone to vote as the rich. Other forms of political engagement are also aimed at the state or at major private institutions, e.g., persuading others to vote, protesting, and filing lawsuits. The value of a political act depends on its impact, which is empirically measurable. For example, a protest may affect the government more or less than a vote, depending on the circumstances.

b. Deliberation: The main purpose of politics is to exchange ideas and reasons so that opinions can become more fair and informed before people take action. A vote is not a good act unless it is well informed and reflects ethical judgment and learning. Participation in meetings is good, especially if the meetings include ideologically diverse people, operate according to fair rules and norms, and conclude with agreement. The use of high-quality news and opinion sources is another indicator of deliberation.

c. Public work: Citizens create public goods by working together--especially in civil society, but also in markets and within the government if these venues are reasonably fair. Public goods include cultural products, the creation of which is an essential democratic act. Relevant individual-level indicators include "working with others to address a community problem" (a standard survey question) or--specifically--participation in environmental restoration, educational projects, public art, etc. Perhaps the best indicators are not measures of individual behavior but rather assessments of "the commonwealth," which is the sum of public goods.

d. Civic republicanism: Political participation is an intrinsically dignified, rewarding, and honorable activity, particularly superior to consumerism. It is implausible that voting once a year could be dignified and rewarding; but deliberation or public work could be.

Civic participation is not only a means to change society; it is also part of the citizen's life. Thus we also need to consider:

2. Theories of the good life

a. Critical autonomy: The individual should be as free as possible from inherited biases and presumptions. We should hold our opinions and roles by choice and revise them according to evidence and alternative views. Not only should people choose their substantive political values, but they should decide, after due reflection, whether or not to engage politically.

b. Eudaimonism: A good life is a happy life, if happiness is properly understood. (And that's a matter of debate.) The happiness of all human beings should matter to each of us, which implies strong and universalistic moral obligations.

c. Communitarianism: We are born into communities that profoundly shape us. Although we should have some rights of voice within our communities and exit in cases of oppression, true autonomy is a chimera and membership is a necessary source of meaning. Participation in a community is essential, but what constitutes appropriate participation is at least somewhat relative to local norms.

d. Creativity: The good life involves some measure of innovation, expression, and the creation of things that have lasting value. Creative work can be collaborative, in which case it requires civic engagement.

These two lists could be combined to create an elaborate grid or taxonomy (which would become 3-D if we added substantive political goals). I'm struck that especially my second list looks rather idiosyncratic, even though my intention was merely to summarize prevailing, mainstream views. I'm not sure what that says about me or this subject.

*I have a self-imposed policy against identifying other people who attend meetings with me.

Posted by peterlevine at 2:10 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 30, 2007

my new book

(Chicago) Yesterday, we received a copy of my new book, The Future of Democracy. I don't know whether it's seemly to post advertising copy for one's book on one's own blog, especially if one wrote the copy oneself. I once posted a CIRCLE press release here. I had mostly written the text myself, and it quoted me as "Peter Levine." Someone remarked, "Attributing a quote to yourself on your own blog is bad form." But I was in a big hurry that day (the morning after an election). This time I have no excuse, yet I am pasting my own third-person summary of my own book below.

The Future of Democracy: Developing the Next Generation of American Citizens is a manifesto for youth civic engagement, based on a critical review of recent research. CIRCLE’s director, Peter Levine, is the author of this book, but it is based on work by our staff, grantees, and advisory board, among others. All proceeds will benefit CIRCLE. The book was commissioned by Tufts University Press/University Press of New England for its Civil Society Series and was published in June 2007.

The Future of Democracy begins by defining "civic engagement." Moving beyond a list of actions and attitudes, Levine proposes some essential principles. He then argues for broad civic engagement as a path to social justice, efficient and responsive institutions, diverse cultures, and meaningful human lives. Next he asks why we should be especially concerned about young Americans’ civic engagement. Not only does engaging young people create lasting skills and habits, thereby strengthening American democracy; it also helps young people to develop in healthy and successful ways.

At this point, The Future of Democracy examines recent trends in civic engagement among American youth, finding a mix of bad news and promising signs. Young Americans are increasingly likely to volunteer and are highly tolerant. Some are inventing exciting new forms of civic engagement, including online methods. On the other hand, they score poorly on assessments of civic knowledge, they are relatively mistrustful of other citizens, they are less likely than in the past to join or lead traditional membership organizations, and they usually vote at low rates. Most are skeptical about their own power to make a difference in their communities.

The rest of the book explores two basic models for understanding these challenges. The first is a "psychological deficits" model. It assumes that there are problems with young people’s civic skills, knowledge, confidence, and values. These problems are not the fault of youth. Hardly anyone would hold a sixteen-year-old personally accountable for lacking interest in the news or failing to join associations. If we should blame anyone, it would be parents, educators, politicians, reporters, and other adults. Nevertheless, the problems are located (so to speak) inside the heads of young people. We should therefore look for interventions that directly improve young people’s civic abilities and attitudes. Such interventions include formal civic education, opportunities for community service, and broader educational reforms that are designed to improve the overall character of schools. The Future of Democracy devotes a chapter each to schools, universities, and community-based organizations that serve youth.

An alternative to the idea of psychological deficits is an "institutional reform" model. This paradigm assumes that there are flaws in our institutions that make it unreasonable to expect positive civic attitudes and active engagement. For example, citizens (young and old alike) may rightly shun voting when most elections have already been determined by the way district lines were drawn. They may rightly ignore the news when the quality of journalism, especially on television, is poor. And they may rightly disengage from high schools that are large, anonymous, and alienating.

If this model holds, then we do not need interventions that change young people’s minds. Civic education that teaches people to admire a flawed system is mere propaganda. Instead, we should reform major institutions. The Future of Democracy argues for specific institutional reforms in schools, the news media, and elections.

This book is not a polemic in favor of one basic model over the other. In the final chapters, Levine argues that we need a broad movement to improve civic education while also reforming the institutions in which citizens engage. We must prepare citizens for politics, but also improve politics for citizens. Neither effort can succeed in isolation from the other. Educational curricula, textbooks, and programs, if disconnected from the goal of strengthening and improving democracy, can easily become means of accommodating young people to a flawed system. But political reform is impossible until we better prepare the next generation of citizens with appropriate knowledge, skills, habits, and values. Students should feel that they are being educated for citizenship, but also that they can help to renew American democracy.

184 pages. $27.95 (cloth). ISBN 1-58465-648-4

available from UPNE or from Amazon

Posted by peterlevine at 12:01 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

May 29, 2007

discussing current issues in schools

(Chicago) Surveys consistently find that most American students discuss current events in their classrooms and feel free to express their own views in these discussions. For instance, according to CIRCLE's 2006 survey, three-quarters of current students ages 15 to 25 reported that they had the opportunity to discuss current political and social issues in their high school courses. The vast majority (80%) reported that they were encouraged to form their own opinions regarding these issues.

Scholars call the combination of time devoted to discussion plus tolerance of multiple perspectives an "open classroom climate." Experiencing an open classroom climate seems to predict all kinds of good outcomes (see PDF).

Yet, as Diana Hess notes, classroom observations consistently find that the vast majority of time in social studies classes is devoted to lectures; real deliberations of current issues are exceedingly rare.

How to square those two results? Hess suspects that students' reports of "open classroom climate" are misleading. I'd put it this way (speculating a bit): Most kids recall that at one time or another, their peers and a teacher discussed a controversial issue. Most students also think that their teachers are basically nice people. Therefore, if you (a high school student) say to Mr. Jones, "What did you think about Bush's speech last night?" or, "I'm really mad about the abortion decision," Mr. Jones will not bite your head off. He may even encourage your interest by saying something supportive--regardless of the position you take. He's probably interested in current events himself, if he teaches social studies. But he will soon call class to order and get back to the required material. If you are surveyed about the "classroom climate," you will say it was "open," even though there was no real discussion.

Hess's most intriguing suggestion: Perhaps the modest positive correlations that we observe between open classroom climates and civic engagement are the combination of no effects from average classrooms and transformative effects from real deliberations. Her research-in-progress will test this hypothesis.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:34 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 28, 2007

the Democratic primary

State primaries are the only contests that really count for selecting a presidential nominee. The national population never weighs in, which notoriously means that people count for a lot more in New Hampshire than in, say, Maryland. Nevertheless, the candidates are surely interested in their standing among all Americans who register with their party. That's partly because their level of national support will influence state primary voters. And it's partly because the primary calendar is so compressed and unpredictable this year that it's risky to rely on particular states.

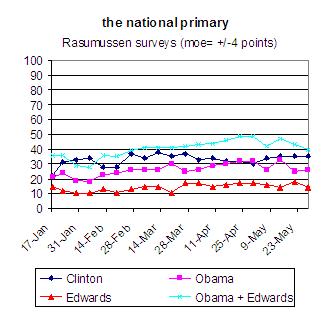

Here, then, is a graph showing support for Senators Clinton, Obama, and Edwards among likely Democratic voters nationwide. (Source for the data.)

The three leading candidates have gained since January, at the expense of "don't know/undecided." Senator Clinton quickly rose to the mid-30-percent range and has then had very stable support. Support for Senators Edwards and Obama has been more volatile and has sometimes traded-off. For example, during the third week of March, Obama gained at Edwards' expense, but then that trend reversed. It's as if 35% of the Democratic electorate has settled on Senator Clinton, and the rest prefers an alternative--but hasn't decided who that should be.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:56 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 25, 2007

November Fifth Coalition: great examples

(Medford, Mass.) With help from the Democratic Governance Panel of the National League of Cities, the November Fifth Coalition has written up six excellent examples of communities in which broad public deliberation has addressed serious, difficult issues, from crime to sprawl to a major budget deficit. These examples need to be part of the public debate, so that candidates, reporters, and ordinary people understand the potential of citizen's work.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:00 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 24, 2007

why not to think about "youth turnout"

However, the blue trend shown above masks enormous variation. The proportion of eligible under-25s who voted was about 36% in 2000, 19% in 2002, and 46% in 2004. In 2004, 69% of eligible voters under 25 turned out in Minnesota, compared to 36% in Arkansas: almost a two-to-one ratio. (See this map.) These huge gaps should turn our attention away from "youth" (whose behavior varies depending on the circumstances) and toward elections. What made the 2004 campaign in Minnesota so much more interesting than, say, the 2002 campaign in Mississippi? Could the former have been a competitive race with high stakes?

Enhanced competition would make much more difference than civic education. It can even seem mendacious to exhort kids to vote in a civics class, if most students don't live in places where their votes count.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:01 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 23, 2007

philosophy and concrete moral issues

The Philosopher's Index (a database) turns up 25 articles that concern "trolley problems." That's actually fewer than I expected, given how frequently such problems seem to arise in conversation. Briefly, they involve situations in which an out-of-control trolley is barreling down the tracks toward potential victims, and you can affect its course by throwing a switch that sends it plowing into a smaller group of victims, or by throwing an innocent person in front of the tram. Or you can refrain from interfering.

The purpose of such thought experiments is to use our intuitions as data and learn either: (a) what fundamental principles actually underlie our moral choices, perhaps as a result of natural selection, or (b) which moral theory would consistently and appropriately handle numerous important cases. In either case, the "trolley" story is supposed to serve as an example that brings basic issues to the fore for consideration. The assumption is that we have, or ought to have, a relatively small set of general principles that generate our actual decisions.

I do not think this approach is useless, but it doesn't interest me, for the following reason. When I consider morally troubling human interactions and choices, I imagine a community or an institution like a standard American public school. The issues that arise, divide, perplex, and worry us in such contexts usually look like this: Ms. X, a teacher, believes that Mr. Y, her colleague, is not dedicated or effective. How should she relate to him in staff meetings? Or, Ms. X thinks that Johnny is not a good student. Johnny is Latino, and Ms. X is worried about her own anti-Latino prejudices. Or, Ms. X assigns Charlotte's Web, a brilliant work of literature but one whose tragic ending upsets Alison. Should Alison's parents complain? Or, Mr. and Mrs. B believe that Ms. X is probably a better teacher than Mr. Y. Yet they cannot be sure. Should they try to get their little Johnny into Ms. X's class, even if that means insulting Mr. Y? Or should they allow Johnny to be assigned by the principal?

Possibly, philosophy has little value in guiding, or even analyzing, such choices. I would like to think that is wrong, and philosophical analysis can be helpful. But it is very hard to see how trolley problems can get us closer to wise to judgment about concrete cases.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:07 AM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

May 22, 2007

generations and economic inequality

(Indianapolis) According to USA Today (which I get in my hotel room),

Inequality within age groups hasn't changed much. People in their 30s or 60s have roughly the same wealth distribution among themselves as in 1989. What's changed is inequality between age groups.Older people are thriving in wealth and income. Younger people are not. How wealth and income have changed for two age groups, after adjusting for inflation:

• Ages 55-59: Median net worth — the middle point for all households — rose 97% over 15 years to $249,700 in 2004, the most recent year for which data is available. Median income rose 52%.

• Ages 35-39: Median household net worth fell 28% to $48,940. Median income fell 10%.

I'm not sure this widening gap is, by itself, a social injustice. Most people in their thirties today will still be alive and in their fifties twenty years from now. If the fifties continues to be a decade of wealth, they will be fine. In part, this will happen because they will inherit their parents' savings.

But that is a static picture. It could be that the gap is not between decades of age but between generations. The Generation-X'ers could move through life consistently poorer than the Boomers, especially if part of the cause is upward redistribution through tax and social policy--and if the Boomers are spending much of their wealth on imports.

Besides, it's not simply the case that each Boomer has a Gen-X offspring. Some Boomers have no kids. Some Xers are immigrants whose parents live in foreign countries. Some Xers have already lost their parents. There is variation in families' wealth and size in both generations. Thus the enormous aggregate wealth of the Boomer generation could be inherited by the Xers and their kids in very unequal ways. Then inequality within generations would increase as a result of massive inequality between generations.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:03 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 21, 2007

angles on US history

(Indianapolis) I'm attending a meeting on teacher education. During a morning session on the teaching of American history, there was some criticism of a certain national historical narrative that's often retold by children when they are asked what they've learned in school. According to this story, from time to time, Americans have realized that there are problems, such as slavery or segregation; and then the government has solved each problem by law.

Even though this is a celebratory and patriotic narrative, it's not a conservative one. It emphasizes progress by and through government, contrary to a truly conservative national history, which would begin with a self-reliant, faithful people and end with a decadent welfare state. For similar reasons, conservatives should dislike the patriotic iconography of official Washington, with its monuments to Jefferson and Washington as the founders of the government that now occupies vast marble office buildings (including the 3.1 million-square-foot structure named for Ronald Reagan). Certain kinds of populist or participatory leftists may be equally hostile to the progressive/statist story, because it ignores citizens and their agency.

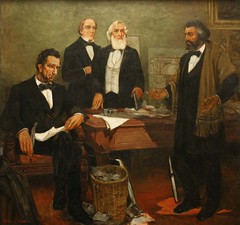

With such thoughts in my mind, I walked over to the Indiana State Museum and saw an exhibition of paintings by William Edouard Scott (1884-1964), an African American artist born in Indianapolis and educated in Chicago and Paris. His works tell a strongly progressive narrative of American history, although not one centered on the government. An easel painting ("Freedom," 1960) shows, from bottom to top, Crispus Attucks being shot by the British in 1775, John Brown (1850), "Abe Lincoln and Fred Douglas" (1863), Thurgood Marshall raising his hand to testify (1954), and an eagle marked "NAACP" downing a bird marked "KKK."

In 1915 alone, Scott painted 20 murals in public high schools in Chicago and Indianapolis. The same year, he painted murals for the office buildings of the Chicago Defender, a major African American newspaper. The Defender editorialized, "When our new buildings are decorated by the works of our own artists we are contributing something substantial to American progress, especially if we obtain the services of well trained men or women."

Note the evocations of racial identity and solidarity, contributions to the American commons, progress, patriotism, excellence, expertise, and equality of women and men. This was a common kind of discourse in the mid-1900s, and one that the state sometimes funded. For instance, Scott won a Federal Arts Project competition in the war year of 1942 to decorate the Recorder of Deeds building in Washington, DC. He produced a mural -- shown above -- of Frederick Douglass appealing to President Lincoln to enlist Black troops in the Union Army. (Douglass himself became the Recorder of Deeds in 1881.) Credit: dbking; some rights reserved.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:01 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 18, 2007

measuring online civic engagement

(Indianapolis) We have an opportunity to ask questions on a national survey that will gauge the extent of civic engagement online. We hope to repeat the same questions in subsequent years to follow trends.

It's hard to get this right. If you ask people whether they do specific activities, such as blogging or posting on message boards, two problems arise. First, these forms of engagement change very rapidly. Yesterday, it was blogging; today it is podcasting and MySpace; tomorrow it will be something else. Second, these activities are only partly "civic" or "political" (by any definition of those terms). If you ask people whether they have created a blog, you can’t tell whether they have done something relevant to politics or community issues. The blig might concern knitting or porn.

Therefore, we might be tempted to ask more abstract questions, such as: "Have you used digital media for civic purposes?" But obviously, most respondents will have no idea what this question means. So we need somewhat abstract questions that can outlast changes in technology, yet ones that people can understand.

I have pasted some draft questions below in case anyone has any advice. These draft items include abstract leads and then concrete follow-ups:

1. Within the last seven days, have you used the Internet to express opinions about politics, a social issue, or a community problem? ("The Internet" includes email and text messages as well as websites.)

If no, skip to question 3.

2. I am going to read you a list of specific Internet technologies. Please tell me whether you used each one within the last seven days to express your opinions about political or social or community issues. a. Email. b. Your own blog. c. Comments on someone else's blog. d. A social networking site like MySpace or Facebook. e. By making a photo, video, or audio and sharing it online. f. By commenting on someone else's photo, video, or audio.

3. Within the last seven days, have you used the Internet to gather information about politics or a social issue or a community problem?

If no, skip #4

4. Now I am going to read you a list of specific Internet technologies. For each one, please tell me whether you used it within the last seven days to gather information about political, social, or community issues. a. Search engines such as Google. b. Professional news websites, such as CNN.com or washingtonpost.com. c. Blogs. d. Social networking sites like MySpace or Facebook. e. Sites that contain shared pictures or videos, such as Flickr or YouTube. f. Wikipedia or another wiki site.

Posted by peterlevine at 3:32 PM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

May 17, 2007

campaigns that stir up civic participation

I don't believe that voting makes sense on its own. If all you do is vote, it takes too much effort to become adequately informed, and the payoff is too small. Very few elections are actually decided by a single vote. However, if you work on public problems in other ways, it makes sense to vote as an additional form of influence. Besides, if you're heavily involved in civic work with other people, they may give you information about the election, which then comes virtually free. And you can persuade them to vote, which multiplies your impact.

The level of local civic engagement is demonstrably much lower than it was even 25 years ago, and that makes it harder to recruit voters. As a response, campaigns could actually organize local civic work as a way of developing supporters. I've looked at the websites of all the major presidential candidates, D's and R's. Most provide ways to "volunteer," but that usually means helping the campaign to mobilize voters. Two campaigns claim a much more ambitious strategy: organizing local discussions and work on issues. We don't yet know the "return-on-investment" in terms of votes for their candidates, nor can we estimate how much positive civic impact these efforts will have. But I think the attempts should be celebrated, and therefore I quote their websites (at the risk of appearing partial to the candidates, which I'm not):

Barack Obama:

For too many people, politics is a bad word. It's not surprising since for many people "politics" means talking heads screaming at each other on TV, or special interests stacking the deck in Washington.John Edwards:We have an opportunity to change that. When politics gets local, when the person talking is your neighbor standing on your front porch, things change.

On June 9th, hundreds of thousands of people will have that experience as we take our campaign to the streets in all 50 states for a nationwide neighborhood walk.

We're calling it Walk for Change, and its success depends on you. ... If you agree to organize a walk, we'll mail you the materials you need to start a conversation with your neighbors about being part of this movement for change. But it can only happen if you're willing to take the leap and put together a June 9th Walk for Change event where you live.

It's not common these days to reach out to a neighbor.

We're more likely to nod quickly and smile when unloading the groceries or walking the dog than we are to stop and talk about the things that shape our common destiny.

But the great issues of our day shouldn't just be topics to fill time between commercials on cable news. These challenges -- ending the war in Iraq, solving the health care crisis, tackling climate change -- affect each one of us personally.

And the solutions to each one will require personal investment from all of us.

That's why it's so important to create this dialogue in your community -- to have a serious conversation about what matters most to your neighbors, and to share with them why this movement for change is personal for you.

John Edwards One Corps' mission is about more than online organizing. We believe that effective advocacy and implementation of change happens when the online world and the offline world work together. John Edwards One Corps offers the components and tools to make this possible.John Edwards One Corps is the official local action arm of the campaign. Thousands of members in chapters covering all 50 states work to help get John Edwards elected president by organizing and attending local events to raise awareness about Senator Edwards and his message and reach out to voters in key areas.

But John Edwards One Corps members aren't waiting until the election to help build the one America we all believe in - we also engage in local service projects and issue advocacy to start transforming America today.

Together, through these and other actions, we can and will make a difference in this country from the ground up.

Together -- as One Corps -- we will create the one America we all believe in.

Posted by peterlevine at 3:59 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

May 16, 2007

choose a fate for Jerry

One: A terraced island rises from a southern sea. Snatches of Gregorian chant can be heard. A barefoot friar, his tonsured pate surmounted by a halo, sings in church Latin: "Brother, you were a schismatic and a heretic. You denied popes, saints, fathers, and councils. To purge your sins, you shall say 50 million Ave Marias. While you perform that penance, your cellmate shall be another American sinner. Brother Fallwell, meet brother Capote."

Two: A giant lotus blossom floats amid puffy clouds in a cerulean sky. A beatific and cherubic personage, seated cross-legged upon the lotus, speaks in Sanskrit: "Beloved Jerry, you were not very compassionate, were you? It is not my will, but the immortal law of nature: you shall be cast down into the briny depths of New York Harbor to feed, as a flatworm, upon the effluvia of Greenwich Village. May you be a self-effacing and contented flat-worm so that you may be reborn the next time as a grub."

Three: Peter, wearing long hair and love beads, waves everyone through the gate even though it's no wider than the eye of a needle. Jerry enters to see, though an acrid haze, clumps of people sprawled on an infinite grassy lawn. Everyone seems to be singing along to Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. An angel arrives to ask Jerry whether he would like to join the saved in the single-sex couples area? Or would he first like to try some heavenly kumba?

Posted by peterlevine at 12:01 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 15, 2007

balance sheets

I spent yesterday at a board meeting, part of which was devoted to reviewing balance sheets. It was my fourth experience with an accountant's report since spring arrived. During the budget portion of any board meeting, I always feel like a "b-minus" student. I can follow the discussion, but only with a delay that prevents me from participating much. If there were a test, I would get about 20 percent of the answers wrong. I would answer some items correctly by repeating phrases, not because I understood the fundamental concepts. (In other words, I would bluff my way to 80%.) Since I have difficulty in following my more competent peers, my attention tends to wander.

However, I do have good motivation, and that keeps me from failing entirely. It seems to me that a balance sheet is an excellent tool for planning in the non-profit world--if the spreadsheet is organized to answer questions that matter for management. If all you want to know is whether you are headed for bankruptcy, then the exercise is not very illuminating. Usually, all you can conclude is that everyone had better work hard and cross their fingers for grants and contracts to come through. If, however, you want to know whether you are putting discretionary resources, such as time or cash, in the right places, a well-constructed balance sheet can be enormously informative.

Posted by peterlevine at 2:43 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 14, 2007

new article on activists' views of deliberation

Rose Marie Nierras and I have just published "Activists’ Views of Deliberation", Journal of Public Deliberation (vol. 3, no. 1, article 4). We interviewed more than 60 practitioners from more than 20 countries to explore the tension between activism and deliberation and to propose some compromises.

We define an "activist" as someone who tries to advance a substantive political or social goal or outcome. A clear case would be someone who seeks government money for a new health clinic. Activism is always an attempt to exercise power, yet some activists' motivations are highly altruistic. They try to develop and employ power for ethical ends. To complicate the definition, we note that many activists feel constrained by democratic procedures or principles. For example, they may drop their demands when they see that they have been outvoted or have lost a public argument. They may be sincerely interested in learning from rival perspectives; and they may try to help other people to become independent political agents with goals and interests of their own. In all these respects, activists can be democratic, not merely strategic.Meanwhile, an organizer of a public deliberation is someone who helps people to decide on their collective goals and outcomes. A clear case would be someone who organizes a forum to discuss how much money the government should raise in taxes and how the funds should be spent. To organize such a deliberation means suppressing or deferring one’s own views about state spending in the interests of promoting an open-ended conversation.

Nevertheless, organizing a deliberation is also an exercise in power. It requires making substantive decisions that can be controversial. Even to invite people to a deliberative session, one must give oneself the right to define the scale and scope of the community, to identify certain issues as important, and to select a method or format for discussion. Even if the process is very open-ended, organizers may rationally predict that a particular outcome will emerge. In such cases, they may use deliberation as a tool to obtain support for the outcome they want.

In short, activists and organizers of deliberations are not sharply distinguishable. It is not only activists who have agendas, desired outcomes, and some degree of power. However, the two groups cluster at opposite ends of a spectrum. At one end, politics is strategic and oriented toward policy goals (albeit constrained by procedures or ethical principles). The main evidence of success is achieving the desired outcome. At the other end of the spectrum, politics is open-ended; the main evidence of success is a broad, fair discussion leading to a set of goals that may be unanticipated at the outset.

If one stipulates that an activist has the right agenda and fully appropriate plans, then it may seem unfair to saddle him or her with the norms of deliberation, which require listening to other people, providing neutral background materials, sharing control of the process, etc. But it is generally unwise to assume that one's own agenda is right. The value of deliberation lies as much in the listening as in the speaking; as much in the opportunity to learn as the chance to persuade. Learned Hand said, "The spirit of liberty is the spirit which is not too sure that it is right; the spirit of liberty is the spirit which seeks to understand the minds of other men and women; the spirit of liberty is the spirit which weighs their interests alongside its own without bias." That is the best argument for deliberation, although there is certainly also a case to be made for forceful political action.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:03 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

May 11, 2007

trust and participation

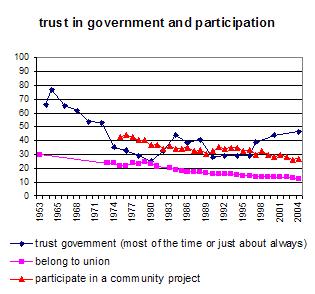

This is just to illustrate my argument from last Wednesday. I claimed that we cannot have massive new government programs without public trust, unless the programs are very simple and transparent--which is virtually impossible in the case of health care. The necessary trust has eroded, in part because people don't belong to participatory groups that seek their voluntary support and that influence the state. Unions are a major example of such groups.

This graph cannot demonstrate a causal relationship among the three trends: falling trust, declining union membership, and declining participation at the local level. But I hypothesize a connection.

By the way, this graph is my belated response to a comment by David Moore, which I had missed.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:07 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 10, 2007

stay tuned

Th Ad Council and the Federal Voting Assistance Program are launching public service announcements (also known as TV ads) "to promote youth civic engagement. ... An extension of their ongoing campaign to encourage young adults to exercise their right to vote, the new PSAs urge young adults to become involved in their communities by voting, volunteering and becoming informed about current events." The press release cites our 2006 survey:

According to FVAP, during the last twenty-five years there has been a dramatic decrease in voter turnout among 18-24 year-olds. In addition, a 2002 report conducted by The Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning & Engagement [CIRCLE] found that 57 percent of American youth aged 15-25 are completely disengaged from civic life and politics.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:23 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 9, 2007

lessons from the health care defeat

At the Democratic presidential debate in South Carolina, the candidates were asked: "What is the most significant political or professional mistake you have made in the past four years? And what, if anything, did you learn from this mistake which makes you a better candidate?" Senator Clinton replied: "Certainly, the mistakes I made around health care were deeply troubling to me and interfered with our ability to get our message out."

I would love to know what mistakes she thinks she made and what she learned from them. I would be sincerely interested in her full response--if she could give it candidly--because she is highly intelligent and experienced and she has a unique perspective as organizer of the 1993 health care reform effort. We cannot know for sure, but I suspect she would disagree with my interpretation, which is the following. ...

The 1993 health reform proposal represented a particular kind of liberalism which is dead. The proposed system would have required an enormous degree of public trust. The details were extremely complicated, so that people (certainly including me) could not understand them. The structure that Clinton proposed would have evolved and shifted as public-sector organizations negotiated with private insurers. Thus the details of the health plan were not only complex; they were unpredictable. Why then should citizens entrust thousands of their dollars per capita to the government? The implicit reasons were: 1) We (in the government) are more trustworthy than those greedy people in HMOs and insurance companies. 2) We will represent you because we are elected. We will act like an interest group in the marketplace, bargaining for advantage; but you will own us. And 3) We are extremely smart. Ira Magaziner is a Rhodes Scholar; we've known him since college days--he has a high IQ.

Those three arguments could work in 1935, when Roosevelt brought lots of talented Ivy Leaguers to Washington to create elaborate programs. It could work in those days because there was more deference to expertise, more hostility to business, and a deeper national emergency--but also because people belonged to institutions with which they had real contracts. They were members of local party organizations and unions that had to pay attention to them in return for their participation. In turn, the New Deal administration was accountable to the unions and the party organizations.

By 1993, that infrastructure was gone. Less than 15 percent of the private sector workforce belonged to unions, which seemed unaccountable even to their shrinking membership. The parties were not organizations at all, but collections of political entrepreneurs. Although we have very pressing reasons to distrust private health insurers, we also have reasons to distrust the government, which gives us urban police departments, the Iraq war, etc.

In the South Carolina debate, Senator Clinton mentioned "getting the message out." I don't think a better message for government-funded health care could work, under these conditions. I'd argue that we cannot have a national health care reform plan unless we use one of these strategies to earn public trust:

1) We could design a government-run system: for example, a single-payer insurance fund that actually set prices for health care. This would give the state enormous power, but also achieve huge savings. In order for people to trust it, they (or a large representative group of them) would have to be actively engaged in writing the law and then revising it. We would need an ambitious series of public deliberations involving a representative sample of citizens. As a charter member of the Deliberative Democracy Consortium and a board member of AmericaSpeaks (which organizes such processes), I'm hopeful that this approach could work. However, I must concede that we have no idea whether public deliberations could build trust for an enormously expensive program, especially if well-funded special interests bitterly attacked it.

2) We could rebuild participatory local institutions as the base for stronger government. That's an attractive idea, but one that would take decades to achieve, if we could figure out how to do it at all.

3) We could have some simple and transparent system that was trustable because it was understandable. I don't think that the government could set prices, because that is inevitably complex. Instead, the government would probably have to issue vouchers that people would use to buy insurance. Unfortunately, we would then be stuck with insurance-company profits and marketing costs.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:10 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 8, 2007

"take back our citizenship"

I love this new project created by students at "the U" (the University of Minnesota). They say: "Our goal isn't to get you out to vote. It isn't to support one candidate or another. Our goal is to get you to think about what it means to be a citizen in this country and to think about what role you would like to play. We've seen the power that citizens can have if they choose to take it, and we want you to take it."

Posted by peterlevine at 9:22 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 7, 2007

strategy, scholarship, and passion

Three meetings in the last four days have reminded me of our wonderful human diversity, even though the participants spoke the same language, gathered in similar settings in two cities along our East Coast, and addressed similar topics.

On Thursday, I spoke to a group of human rights activists from the developing world. Their host was the State Department; the setting was a private room in a Washington restaurant of the old, steak-and-bourbon style. I talked about civil society and the kind of politics that begins with citizens, not with governments. Much more interesting than I were the visitors who formed my small audience. There were West African politicians who delivered relatively long and formal comments, standing up to address the room. One man from Nigeria laced his remarks with classical allusions. An Egyptian and a Lebanese, speaking separately, criticized American foreign policy, particularly our inconsistent support for democracy. They were polite but passionate and angry. Afterwards, they asked to have their pictures taken with me, joking that my career as a politician would now be doomed. (It wasn't going anywhere before then.) The Lebanese man complained that US funding agencies want more youth civic engagement in his country. He noted that every young Lebanese took to the streets in protest last summer. Youth engagement is not the problem; governments are.

On Friday and Saturday morning, I participated in a small academic conference on youth civic engagement. My colleagues were mostly psychologists. We sat around a seminar table in a slightly beat-up room high in a skyscraper that belongs to Fordham University. One of our characteristic ways of communicating was to respond favorably to the previous speaker's remarks, adding: "So-and-so from Harvard--or Indiana, or Loyola--has done work on that." Or: "There was a piece about that in ADS in the early nineties." Or: "MTF data show that trend." Because everyone was an empiricist, the norm was to ground claims in facts and statistics. Yet the participants shared strong, implicit moral commitments: to the dignity and value of political participation, the need for equality and justice, and the positive potential of young Americans. Therefore, much of the evidence came from evaluations of highly idealistic programs that were relatively small. The real message was how much young people could achieve if big institutions invested in them.

iThen, on Saturday evening, I joined the Newspaper Association of America (NAA) conference at Tavern on the Green in Central Park. This was a big institution with funds to invest. The participants were American media executives: prosperous, confident, good-humored and jocular. It was like an Ivy League alumni reunion, albeit with more women that you would see if the Princeton class of '65 reconvened. I was served an enormous piece of beef while speakers stood to roast one another.

The next day, as a trustee of the NAA's Foundation, I heard a presentation on youth. The speaker was a market researcher, and his objective was to help newspapers reach young consumers. This is a worthy goal, because we know that newspaper readers are much more active in politics and community affairs. Of course, the motives of the newspaper executives are pecuniary, but that is fine: they could achieve public benefits by investing in young readers

The presenter sounded like a motivational speaker. ("Folks, you're going to have to reach them where they are.") He had six main ideas about young Americans, and each one had its own, professionally designed logo that flashed on the screen. (For instance: "autono-ME" meant the strong desire of young consumers to customize their products.) These aspects of the presentation certainly put me off, but it was quite insightful and based on statistical evidence. It was also rather disturbing, since a picture emerged of young people who are tremendously skillful at finding entertainment that has little public or intellectual or spiritual value. My only doubt about the factual claims in the presentation concerned the future. Generations develop over time. The same people who wore dashikis and love beads in 1968 had been Eisenhower-era suburban kids in 1958. So there is always the possibility that today's teens will rebel or shift dramatically--especially if they encounter passionate arguments like those I heard on Thursday or excellent programs like those discussed on Friday and Saturday.

It's a facile conclusion, but I'll write it anyway. We must somehow combine the political commitment and groundedness of the State Department's visitors with the idealism and empirical rigor of the developmental psychologists and the economic muscle and realism of the media industry.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:41 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 4, 2007

getting out the (French) youth vote

(traveling to New York City) The "Association Collectif Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité, Ensemble, Unis" is quite a mouthful, but its acronym means "enough of the fire" in French (ACLEFEU="assez le feu"). Its List of Grievances (a phrase borrowed from the French Revolution of 1789) could be translated thus:

Our organization, ACLEFEU ..., has seen the cold leftovers of the social revolts that shook the land during the month of November 2005 following the deaths of our children, Bouna and Zyad, at Clichy Sous Bois [where two alleged rioters, hiding from the police, were electrocuted in a power substation]. So that we can say they did not die for naught, we are committed to the mission of going to the people in all their diversity to get them to fill out 'Lists of Grievances.' ... It seemed to us essential to work to stop the fires [of the riots], considering that the best weapon for making oneself heard still remains civic participation in democracy, yet the debate that must precede the choice at the moment of voting is still closed to one part of society, that which merely copes. All citizens must truly have the power of a voice and the ability to express their needs, their proposals, their hopes.

ACLEFEU claims to have collected "20,000 reports, grievances, and even more proposals." It observes, "History seems to repeat itself; today as yesterday the central ideal of the Revolution is clearly evident in the Lists: equality." It goes on to describe the people who submitted grievances:

Far from being unconcerned about politics, many of these people, among whom a majority are between the ages of 18 and 25, express the need to see the parties and elected officials become closer to the people and their real lives. For several years, all the parties have multiplied their forums, general meetings, etc. ... But all this good will does not seem to have convinced the popular classes. The abstention in recent elections, as well as our List of Grievances, proves it. We hope that those who aspire to preside over the destiny of France will know how to take advantage of what we offer here, to build with the residents, with respect for their proposals, a just and courageous politics that attacks, above all, the causes of their insecurity and exclusion. For our part, we have faithfully synthesized the priorities, reports, and proposals from the Lists of Grievances. In the coming months, we will be vigilant regarding the use you make of these popular proposals. We expect to bring all our weight to bear so that the excluded register to vote and choose their [presidential] candidate as a function of his capacity to conduct politics in dialog with citizens.

The actual proposals, as far as I can see, appear rather retrograde. They include heavy regulations on the labor market that might worsen the exclusion of immigrant youth. However, the rhetoric of citizen voice and dialog is impressive, as is ACLEFEU's organizing muscle.

Posted by peterlevine at 6:00 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 3, 2007

transparency and the Millennial generation

Most participants at last weekend's Mobilize conference (median age, about 25) maintained that their generation demands transparency, and this is one of their defining characteristics. In general, I support claims that the Millennials are distinctive. I'd be the last to try to rebut the idea that they are especially idealistic, for example--or especially good at collaborating in decentralized ways. There is evidence to support these assertions, and I want to reinforce a positive generational self-image.

However, I'm not sure about this generation's commitment to transparency. First of all, Americans have been in favor of openness for a long time. According to Robert Wiebe, the Progressives of 1900-1924 believed that:

The interests thrived on secrecy, the people on information. No word carried more progressive freight than publicity: expose the backroom deals in government, scrutinize the balance sheets of corporations, attend the public hearings on city services, study the effects of low wages on family life. Mayor Tom Johnson of Cleveland held public meetings to educate its citizens. Senator Robert LaFollette of Wisconsin heaped statistics on his constituents from the back of a campaign wagon. Once the public knew, it would act; knowledge produced solutions (Weibe, Self-Rule: A Cultural History of American Democracy, Chicago, 1995, p. 163).

Justice Louis Brandeis spoke for the Progressive movement when he wrote, "Sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants; electric light the most efficient policeman" (Other People's Money , New York, 1932, p. 92).

Americans didn't forget about transparency over the next forty years, but for a generation or two it wasn't the major theme it had been before World War I. Then came Vietnam and Watergate, and again "sunlight" was the rallying cry. The Congressional class of 1974 and their nonpartisan allies won the Freedom of Information Act, campaign finance disclosure laws, registration requirements for lobbyists, open-meeting and sunlight acts, open committee hearings, and many similar reforms--all within a space of a few years. The very names of Public Citizen and the Public Interest Research Group suggested a commitment to free information and openness that was characteristic, I would argue, of the Boomers.

If enthusiasm for openness faded slightly, perhaps it was because information, alas, is not power. People do not just need data to act effectively. They also need motivation, coordination with other people, and resources. The open government reforms of 1973-6 were good, but they did not fundamentally change politics.

As for the Millennials--I don't know whether surveys have measured their commitment to transparency. But I do know that they are coming of age in a period when certain important interactions are less transparent, not more so. Who knows how Amazon determines what books might interest you? Back when neighborhoods had independent bookstores, if your bookseller recommended an item to you, you knew why. Not so with Amazon. Likewise, who knows how the National Assessment of Educational Progress is created? In the days when your teacher made up your tests, you at least knew who was responsible and could ask her why she had made her choices. Meanwhile, the national security apparatus has rapidly expanded after 9/11.

Perhaps the Millennials will rebel against all this opacity (the opposite of transparency); or perhaps they will be inured to it. In any case, I don't think their commitment to transparency is one of their defining characteristics.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:30 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 2, 2007

November Fifth Coalition: new materials

I've been working on the website of the November Fifth Coalition, whose purpose is to inject civic themes into the 2008 election. (By "civic," we don't mean civility and consensus, but concrete, active work by citizens--some of which is pretty contentious.)

We have a policy statement on "Putting Citizens Back in the Center of Education." It describes education as not just the job of schools, but as a community-wide function whose purpose is to transmit values, culture, knowledge, and skills to the next generation.

We also have some interesting examples of civic work and a "news" page with clips and blog feeds about civic engagement.

Posted by peterlevine at 2:44 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 1, 2007

American responsibility for the Iraqi civil war

Last week I posted what could be called a "conciliatory narrative" about Iraq (avoiding calling it either a "fiasco" or a "defeat.") Over at Philosophy, et cetera, someone who writes as Dr. Pretorius replied:

The sentence "That conflict is morally our responsibility, because we might have been able to prevent it" [from my blog] is almost certainly false. In, say, Darfur we might have been able to prevent some of the atrocities, and we may or may not be responsible for that. In this case, though, it is morally our responsibility because we caused it, not because we failed to prevent it.Saying this, or saying that "A civil war then broke out," is just a cop out - the civil war didn't just break out (as if it was a matter of bad luck). It was caused by, oh, the speedy overthrowing of a stable dictatorship without any significant planning for what to do afterwards.

I don't want to evade or downplay US responsibility for the war in Iraq. I think it's our fault. However, the philosophical issues are complicated. First, it's problematic to draw a sharp distinction between sins of commission and sins of omission. As an exercise in comparing the two, consider our passivity during the Rwanda genocide versus our (alleged) killing of civilians during yesterday's fighting in western Afghanistan. The number killed in the Rwanda genocide was much larger, and our motives were worse. Yet we directly and intentionally hurt no one in Rwanda, whereas it was American guns that fired yesterday in Herat. I think we did much worse in the Rwanda case.

Then there is the complexity of assigning moral responsibility when an event has many preconditions. Perhaps J. L. Mackie's idea of an INUS condition applies to the Iraqi civil war. Our invasion was an insufficient condition, because the violence required not only our intervention, but also deliberate killings by various Iraqi factions. Our invasion was an unnecessary condition, because the civil war could have started another way, e.g., if Saddam had died of cancer or by an assassin's hand. The invasion was nevertheless a necessary condition of a sufficient condition because Iraqi factions could not have killed each other without our invasion, and once Saddam was overthrown, a civil war was basically inevitable.

That means, it seems to me, that we have complete responsibility for the civil war, and yet Iraqi factions who kill one another also have complete responsibility for it. Moral responsibility is not like a pizza, such that if you get two more slices, I get two fewer. It's more like a virus: you and I can both have it 100%. Which is about where we stand in Iraq.

Posted by peterlevine at 1:36 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack