« May 2007 | Main | July 2007 »

June 29, 2007

trajectories

We've been meeting intensively this week with teens from Prince George's County, MD. We've had 14 hours of class since Tuesday afternoon. All our students happen to be African-American, but they are extremely diverse (as I would have expected). Consider these statements that two of them wrote yesterday:

1. I am a young black African American male I attend -- High School although it is not the best school in the world It still ofers some what of a education. Right now at this point in my life I am trying to get back on the right track study more and stop hanging out with the friends I have that I know won't go anywhere in life based on there action. I am also trying to do better next year than I did this one so when the time comes I can go to college.

2. Hello! My name is Marcus [pseudonym]. I am officially a freshman at -- High School ... . I love to play sports. I joined this program because I was interested in the summary I was given. In my spare time I like to play video games, read, play sports and watch movies. When I grow up I would hope to be a physician. In conclusion, you can see I am just an average teen that would like to make a difference against modern day issues that face young people such as graduation rates, cleanliness of schools, bullying, education, Racism, and the increasing rate of lunch prices. Well, I'm done now, and remember, 1 person can make a difference.

Marcus's father is a graduate of University of Maryland. Note his confidence, his good writing, his general optimism and outwardness. His classmate (quoted first) is much less confident and much more challenged. His brother was murdered, and he's had other trials.

I walked around campus with both of these young men. I'm sure that Marcus was intrigued by the place and felt pretty much at home there. I hope that his classmate, who was much quieter on our tour, could see some realistic connection to the University and didn't find it overwhelming or alienating.

Posted by peterlevine at 4:18 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 28, 2007

click to publish

Posted by peterlevine at 10:28 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 27, 2007

Case Foundation's citizen-centered grantmaking

Stephanie Strom reported yesterday in the New York Times:

In a first, a major foundation is offering the public a direct role in deciding who should receive some of its money, a process typically shrouded in mystery. ... The foundation is asking individuals and small local nonprofit groups to send ideas for improving their communities. A group of judges will select 100 of the submissions received by Aug. 8 and ask for a more formal proposal. ... Another panel of judges will then select 20 finalists, who will receive $10,000 each. And in November, the public can vote on those proposals, and the four that receive the most votes will get an additional $25,000.Strom was most interested in the process, which is innovative. But the substance of the grant competition is equally important. Case is looking for "citizen-centered" work, as defined in a key paper by Cindy Gibson. Citizen-centered projects start with broad-based, open-ended deliberations about what should be done. People are not mobilized or persuaded to do what leaders or experts think. Citizen-centered projects go beyond deliberation and discussion to include direct action, from which people learn and then improve their discussions.

Cindy Gibson also has a new blog, Citizen Post, "the one-stop place for all things citizen-centered--the way democracy should be." Although it officially launches this week, it already has a series of thoughtful posts.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:31 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 26, 2007

Caroline Levine, Provoking Democracy: Why We Need the Arts

I'm not the only member of my family to have published, during the month of June 2007, a book with "democracy" in the title. My sister, Caroline Levine, is the author of the new book Provoking Democracy. Caroline uses court cases and controversies from the 20th century to illuminate the value of art for democracy--and vice-versa. Her book is full of stories that are amusing, suspenseful, and moving. Here is an excerpt that gives a sense of her overall argument:

Democratic forms of government are typically better at tolerating discord and dissension than other political models; but it has become a commonplace to argue that art for democratic public spaces should reflect current majority tastes and values. The controversies described in this chapter point to a different solution: art that is taken as a reflection of "the people" here and now is partial and inadequate, since democratic collectives are always and necessarily self-divided, productive of difference and capable of transformation. The avant-garde is better than any referendum at capturing a changing and dissonant understanding of "the people."

Posted by peterlevine at 7:59 AM | Comments (4) | TrackBack

June 25, 2007

an AARP for youth (II)

In January of 2005, I wrote a post about "an AARP for youth"--a national organization that would lobby for young people's interests, as a counterpart to the powerful American Association of Retired People. Lately, two different people have asked me about this idea, which is being actively considered. I still think the concept is worth consideration.

Young people as a category have interests that conflict with those of older generations. When the government borrows money, young people pay most of the interest over the course of their lifetimes. Interest currently constitutes eight percent of annual federal spending. If the borrowed money is spent on Medicare, Social Security, or other programs targeted at retirees, young people get little direct benefit.

Eighty percent of people in the military are younger than 36; thus higher military salaries would benefit youth, but combat deployments disproportionately harm them. Cutting down a hardwood forest generates goods and jobs now, but denies the forest to later generations. On the other hand, government subsidies for college tuition (unless they are poorly structured) should lower costs for young people and increase their lifetime earning capacity.

There is always a temptation to take benefits now and pass the costs on to later generations. Jagadeesh Gokhale and Kent Smetters ("Fiscal and Generational Imbalances: An Update," National Bureau of Economic Research, August 2005) calculate that if current policies were sustained, Americans who are now older than 14 would (over the course of their lives) reap $11 trillion more from Social Security than they pay in, whereas today’s children and subsequent generations would pay $1.5 trillion more in Social Security taxes than they received from the program. However, current policies would leave Social Security in an enormous deficit. That projected gap will have to be closed by increasing taxes and cutting benefits by a total of about $8 trillion. Unless those painful changes start soon, Gokhale and Smetters argue, they will be entirely borne by people who are now younger than 15.

These estimates rely on various assumptions about growth, productivity, and policy; they are by no means precise. But they reflect a reasonable guess that today’s adults are taking trillions of dollars from today's children and future generations by borrowing instead of paying for their own benefits. That might be acceptable if it were a fair and public decision, perhaps grounded on the argument that future generations will be so much better off--thanks to improving technology and bequests from their parents--that they should pay for today's retirees. However, this rationale is rarely acknowledged or fairly debated. Young people vote at such low rates that their interests are simply overlooked.

These are arguments (lifted, by the way, from my new book) that young adults have interests that are unrepresented. Hence the move to create an AARP for young people. But here are some objections to the idea that should, I think, be considered:

1) Perhaps it wouldn't be such a great thing to have another organization like the AARP, which is a special-interest lobby that may undermine the public interest (by, for example, protecting programs for the elderly even when they should be trimmed). If young people had an equivalent to the AARP, there would be more balance in social policy. But other groups would still be left out, e.g., young children and middle-aged folks (like me!). And if every age group had a lobby, politics would become even more a matter of negotiations among interest groups, rather than deliberations about the common good.

2) A practical concern: There are no programs that affect and benefit almost all youth. AARP probably hangs together because all retirees qualify for Social Security and Medicare. But only a small minority of youth benefit from federal financial aid. Another groups gets welfare or job training; another group enrolls in community colleges; and some are in the military. Many are not in programs at all. Arguably, programs should be built for all youth, e.g., universal civilian national service. But we have to decide whether that proposal is a good idea on its merits. It's not a good idea just because it would unite young adults into an interest group.

3) Pyschological factors: If elderly people identify as old, it could be because that's the final stage of life--and because they are all influenced by massive universal programs for retirees. Young people don't necessarily identify as young, because they expect to enter other stages of life. Also, their life experiences are enormously diverse--compare a Harvard law student with a state prisoner. Thus I'm not sure how much solidarity could be built around the theme of age.

Posted by peterlevine at 3:38 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 22, 2007

youth mapping

(Milwaukee) Next week, we start an intensive program for teenagers in Prince George's County, MD who will choose an issue, conduct interviews of relevant adults, and depict the results in the form of maps and diagrams. We will be testing software that's being designed by our colleagues at the University of Wisconsin. Our goal is to develop and refine a software package that will easily add an element of research to service-learning programs, as kids identify assets, relationships, and sources of power and thereby make their civic work more effective.

Near the beginning of the first day, I want to show the kids great products that their peers around the country have created. Students at Central High School in Providence have built a multimedia website about their own school that's pretty absorbing. I can find good youth-produced videos, like the ones collected on What Kids Can Do. I've personally worked with kids to create a "commons" website for Prince George's County that has some video, audio, text, and maps. My organization, CIRCLE, has funded kids in Tacoma, WA to create this interesting documentary on teen pregnancy. We've also funded other youth-led, community-based research projects. They are listed here, although some don't yet have public products.

We want our team this summer mainly to work with maps and diagrams, perhaps illustrated with some video and audio footage. Although "mapping" is a common activity for youth today, I can find few youth-produced maps online that might inspire our team. In one sense, this is good news--we feel that we're doing something significant by creating templates for more exciting map projects. On the other hand, I'm sure there are good products out there, and I would like our team of kids to see them.

Posted by peterlevine at 1:53 PM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

June 21, 2007

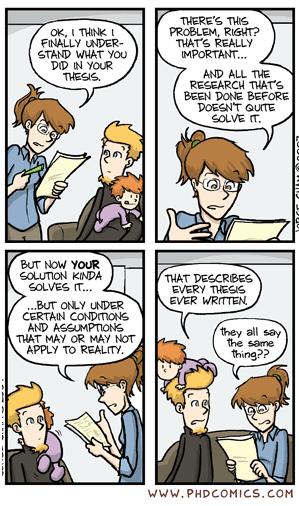

I think I've read this dissertation ....

(From Piled Higher and Deeper.)

Posted by peterlevine at 9:12 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 20, 2007

the changing transition to adulthood

Consider that:

In 1970, there were about 1.5 million Americans above the age of 25 who were enrolled in some kind of school. In 2004, about 7 million people were over 25 and still in school (pdf).

In 1970, almost half of Americans between the ages of 18 and 25 were married. Today, 15 percent of that age group is married. (pdf)

The median age of first marriage for women is 25. In 1970, it was 20.8. I think most of the increase reflects later marriage by middle-class, college-educated women.

In 1961, about 4 percent of all first births were to mothers over the age of 30. By 1994 almost one third of first births were to mothers in their thirties or forties (and I wish I had more recent statistics).

American parents spend an average of $38,000 per child while their children are between the ages of 18 and 34--a huge downward flow of cash.*

Many young Americans are delaying the traditional markers of full adulthood (finishing school and beginning a career; marrying and having a first child), thereby transforming the third decade of their lives. They are receiving massive investments in the form of training and educational experiences, paid for in large part by Mom and Dad. They are entering a work force in which success seems to depend on education, travel, internships, and other learning experiences--so much so that it takes until nearly age 30 to start really working and building a family.

On the other hand, many Americans are not in a position to stay in school through their 20s or to receive tens of thousands of dollars in subsidies from their parents after age 18. Whereas the transition to adulthood has lengthened for middle- and upper-middle-class young people, it is no more protracted today for poor youth than it used to be. They are still on their own when they finish high school, with little investment from the government or families. They are most likely to interact with the government as members of the military or as prisoners.

It's time, I think, to focus on the supports that working-class adults receive during their twenties, while their middle-class contemporaries are developing skills and interests.

--

*Frank F. Furstenberg Jr., Ruben G. Rumbaut, and Richard A. Settersten Jr., "On the Frontier of Adulthood," in Settersten, Furstenberg, and Rumbaut, eds., On the Frontier of Adulthood: Theory, Research, and Public Policy (University of Chicago Press, 2005):

Posted by peterlevine at 11:07 AM | Comments (3) | TrackBack

June 19, 2007

why service learning policy is stuck

Service-learning (the intentional combination of community service with academic study) is a pretty significant phenomenon. According to CIRCLE's fact sheet, "As of February 2004, over 10 percent of all K-12 public school students and 28 percent of all K-12 public institutions are involved in some type of service-learning, affecting approximately 4.7 million K-12 students in 23,000 public schools." Yet the number of students who participate seems to have reached a plateau, and federal support (through the Learn & Serve America program) has declined.

At last weekend's conference, the question was raised: Given the large quantity of research on service-learning, why hasn't policy improved? In short, why doesn't the research affect policy? Many of my colleagues felt that the problem lay with jargon-filled, overly complex research that isn't translated or disseminated effectively.

That could be, but I have another explanation. Learn & Serve America supports an opportunity for schools and kids (i.e., service-learning) by funding it. That is a classic approach to educational policy, but it is not the dominant approach in our decade. The No Child Left Behind Act (which is just a name for the whole Elementary and Secondary Education Act) provides, mandates, supports, or authorizes very few opportunities at all. Instead, it defines outcomes and offers financial support (albeit, too little) for schools that reach those outcomes. (More on this distinction here.)

The reason for focus on outcomes is a profound lack of trust for schools. Conservatives distrust public schools because they are state monopolies, and unionized to boot. But it is equally important that many liberals distrust schools for being corrupt, reactionary, and discriminatory. I have been harangued by liberals and civil rights activists who completely support the structure of No Child Left Behind (which, indeed, was drafted by liberals). They believe that if you give money to schools to provide opportunities, the money will be wasted or channeled to privileged kids, and the opportunities themselves will be distorted beyond recognition. Their strategy is to hold schools accountable for core outcomes, focusing especially on kids who are likely to suffer discrimination. They are happy to let schools choose their methods. If service-learning actually enhances student performance, fine. But they will not directly support service-learning or any other opportunity through federal policy.

Very little of the existing research on service-learning is relevant to this situation, which is why (I believe ) it has so little impact on policy. To make a difference, the research would have to:

a) Show that mandates or funding for service-learning on a large scale actually make a positive difference in typical and struggling schools (not merely in excellent "boutique" schools). Recent research by Davila and Mora and by Kahne and Sporte do find such positive effects.

b) Show that the strategy of No Child Left Behind is flawed for its advertised purposes (raising student performance and equity). Or ...

c) Figure out how to make schools, which are so deeply distrusted, more trustworthy by actually reforming them.

[update, June 20: The Senate appropriations subcommittee seems to have approved a 5.4% increase in Learn & Serve America, by a voice vote. If that change survives, it will be the first increase for a long time.]

Posted by peterlevine at 9:55 AM | Comments (3) | TrackBack

June 18, 2007

father's day

(Rehoboth, MD DE) We're at the beach for a quick Father's Day getaway. Back online tomorrow.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:44 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 15, 2007

youth voting rose in '06

CIRCLE released our analysis today of the Census Department's 2006 voting survey. (The data were released yesterday.) We found that the turnout of young people rose to 25.5%--a low rate, admittedly, but a nice rise compared to 2002. It was also the second consecutive increase. The trend is especially impressive because turnout of the whole population hardly increased at all in 2006. The boost appears to be a youth phenomenon, caused either by the Millennials' political consciousness or by deliberate youth turnout operations--or both.

On a personal note, I'm relieved that the estimate we released on the day after the election, based on exit polls and accompanied by lots of caveats about the margin of error, turned out to be very close, even slightly conservative.

Meanwhile, I'm helping to run a conference for "emerging scholars" who study service-learning. Each emerging scholar--a graduate student or a junior professor--presents a paper and is assigned senior mentors who are scholars or advocates. This is a deliberate effort to strengthen and diversify the next generation of scholars who study a form of education that appears, at the least, to be highly promising.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:43 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 14, 2007

Günter Grass’s memories

The June 4 New Yorker presents an excerpt from Günter Grass’s memoir, Peeling the Onion. For the first time, we get the novelist's own lengthy account of his experiences in the Waffen S.S., a story that he had suppressed for about 60 years. The New Yorker (or possibly Grass) chose an excerpt that is action-packed. There is not too much rumination about what the experience meant or why he failed to mention it during the decades when he bitterly denounced German hypocrisy about the Nazi past. Instead, the thrilling adventures of a young man at war make us highly sympathetic. We root for him to survive, notwithstanding the double-S on his collar. And as we read the exciting story (under the flip headline of "Personal History: How I Spent the War"), our eyes wander to amusing cartoons about midlife crises.

I would not be quick to condemn a 16-year-old for joining the S.S., although that was a much worse thing to do than joining a gang and selling drugs, for which we imprison 16-year-olds today. For me, the interesting moral question is what the famous and accomplished adult Günter Grass did with his memories.

So ... why run an excerpt that is mainly about his exciting adventures in the war? Why not write about the 60-year cover-up? Why introduce the memoir in English in a very lucrative venue, America's most popular literary magazine? Also, why write only from his personal perspective, saying almost nothing about the nature of the S.S. or its reputation among German civilians at the time?

Grass cannot recall precisely what the S.S. meant to him when he was assigned to it. But he thinks it had a "European aura to it," since it comprised "separate volunteer divisions of French and Walloon, Dutch and Belgian. ..." The von Frundsberg Division, to which he was assigned, was named after "someone who stood for freedom, liberation." And once Grass was in the S.S., where he was exposed to many months of training, "there was no mention of the war crimes that later came to light."

This paragraph continues: "But the ignorance I claim cannot blind me to the fact that I had been incorporated into a system that had planned, organized, and carried out the extermination of millions of people. Even if I could not be accused to active complicity, there remains to this day a residue that is all too commonly called joint responsibility. I will have to live with it for the rest of my life."

I do not know whether the factual claim here is credible. I must say I find it very surprising that in the course of a whole autumn and winter of S.S. training, there was "no mention" of war crimes. Maybe the details of the death camps were not discussed, but I am amazed that the S.S. trainers never talked in general terms about violence against Jewish, Gypsy, Slavic and other civilian populations. That was a different kind of "European aura": the attempted slaughter of several whole European peoples.

Regardless of what precisely Grass heard in his S.S. training, I find his reflection on "joint responsibility" troubling. He says he has no "active complicity," even though he had joined the S.S. when he could have found his way into the army. His involvement in the Holocaust is passive: "I was incorporated into a system. ..." As a result of this bad moral luck, he feels "joint responsibility"--a term that is "all too often" used. (Actually, I find this sentence hard to interpret and evasive. Is the term "joint responsibility" used when it does not apply? Does it apply in his case?) Finally, Grass emphasizes the distress that his passive complicity has always caused him and will continue to cause him for the rest of his life. There is no hint of an apology for the harm that his active decision to join the S.S. might have caused other people. And then the memoir proceeds to make him its hero--his survival a happy ending.

I would forgive Grass instantly if he took personal responsibility for what he did at age 16 and 17. I am not so sure I like how he is behaving at age 80.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:43 AM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

June 13, 2007

a new progressive era?

Tomorrow, I'm presenting at the Labor and Employment Relations Association (LERA) National Policy Forum. I've been invited to speak on a panel entitled, "A New Progressive Era? The Influence of State and Local Initiatives on National Policy." Presumably, I was invited because I wrote a book entitled The New Progressive Era. I don't have much to say about the real topic of the panel, which is whether "recent local and state initiatives on employment and labor relations" will lead to "national level policies." If I'm going to be any help at all, I need to reflect on general parallels between the Progressive Era (1900-1924) and today. This will also be a chance to present a different view of the original progressive movement than the one I held in the 1990s.

Huge changes occurred during the Progressive Era, and the word "progressive" had such positive connotations at the time that proponents of every important development liked to call it "progressive." (Walter Lippmann observed in 1921 that "an American will endure almost any insult except the charge that he is not progressive.")

Among the important changes that could be called "progressive" were: administrative centralization in industry and government; specialization, professionalization, and the cult of science and expertise throughout society; the increased use of formal rules and regulations in both government and business, often to protect consumers; reform legislation designed to reduce the impact of money in politics; the "efficiency movement"; the growth of organized labor (which mimicked forms of administration seen in business and the state); and a new ideal of citizenship. Whereas the 19th century citizen was supposed to be a loyal and enthusiastic member of an identity group, the progressive citizen was supposed to be an independent, informed judge of public policies. That ideal led to concrete reforms such as the secret ballot and attacks on political parties. Overall, politics became less "popular," more a matter of expert administration; and turnout dropped accordingly.

In my book, my heroes were Robert M. La Follette, Sr., Jane Addams, John Dewey, and their associates. Although these three surely deserve the label "progressive" (for instance, La Follette won the Progressive Party nomination), they were ambivalent about the main trends I mentioned above. In the Library of Congress, I read a book manuscript that La Follette wrote--but for some reason never published--criticizing the state government of Wisconsin for becoming overly professionalized, expert-driven, bureaucratic, and distant from ordinary people. Jane Addams battled the Chicago Democratic machine but wrote appreciatively of the emotional connection between a machine Alderman and his constituents. Compared to the "village kindness" of the ward boss, she wrote, "the notions of the civic reformer are negative and impotent .... The reformers give themselves over largely to criticisms of the present state of affairs, to writing and talking of what the future must be; but their goodness is not dramatic; it is not even concrete and human."

I thought that my favorite progressives were characterized by three main principles:

They were democrats, willing to do what the public wanted rather than push policies that they favored for theoretical reasons. That was the heart of Dewey's pragmatism: a rejection of general rules and a commitment to democratic processes. It is what separated all of my heroes from the Socialist Party of the time, which used democratic procedures but which was wedded to Marxist principles. La Follette embodied Deweyan pragmatism even before Dewey wrote any influential books. As a candidate, La Follette typically avoided strong policy proposals but argued for a more democratic process and pledged to do what the people wanted. Most of his policies were procedural--campaign finance, lobby disclosure, and the like. They were egalitarians, critics of political processes that gave some people more power than others because of money, secrecy, or administrative structures. They loved deliberation. La Follette printed the following words by Margaret Woodrow Wilson on the front cover of his popular Weekly in 1914: "No wonder that [politicians] do not always know what the people want. Let us get together so that we may tell them. All of our representatives are organized into deliberative bodies. We, whom they represent, ought also to be organized for deliberation. When this happens, and then only, shall we vote intelligently." For these reformers, democratic participation did not mean developing preferences and expressing them in the ballot box or the marketplace. It rather meant discussion, listening and persuading--collective education.

I would now add a fourth principle:

They understood that deliberation and democracy could not be achieved through changes in rules and processes alone. Citizens needed new skills and identities in order to participate. Culture-change was essential. This explains why they built model institutions with strong democratic cultures, such as Hull-House, the Chicago Lab School, and the University of Wisconsin's Department of Debating and Public Discussion, which sent 80,000 background papers per year to citizen groups.

The people I'm calling Progressives faced several serious dilemmas that we still haven't solved. It was hard to sustain public support for "democracy" without promising concrete social and economic changes. Yet to promise a particular policy, such as a child-labor law, meant circumventing public discussion and dialogue. Progressives appealed to the general or public interest, but people understandably identified with narrower group interests. The Progressives built impressive small institutions that were genuinely deliberative and democratic; but they never figured out how to increase the scale of these efforts. For example, Deweyan educational practices, when implemented on a large scale, became grotesque parodies of his ideas. Finally, despite their ambivalence about expertise and centralization, the Progressives never designed large and strong institutions that remained participatory and egalitarian. The Wisconsin state government that La Follette criticized as bureaucractic and arrogant was the very same government that he had built during his own gubernatorial administration. Although he wasn't directly responsible for how it developed, he did not know how to stop it from becoming a Weberian bureaucracy.

Despite these dilemmas, I believe the Progressives whom I admire contributed an enormous amount to mid-20th-century liberalism. Most progressives (including Dewey) were ambivalent about the New Deal. But the New Deal benefited from the open deliberations of the Progressive Era (which generated a host of creative policy ideas) and from ordinary people's trust in public institutions. People trusted the government and were willing to spend tax money on it because--among other reasons--many teachers, social workers, conservationists, and other public employees had Deweyan traditions of working collaboratively with laypeople. For instance, neighbors of Hull House and its employees had real mutual accountability and respect. So when Hull-House was "taken to scale" in the New Deal, people could feel a place in the new government agencies.

In short, Progressive-Era pragmatism contributed to something that it wasn't--to the ideology of mid-century liberalism that dominated government from the FDR to LBJ. Liberalism was a robust ideology because it had: a comprehensive diagnosis of social problems, a store of moving rhetoric and famous leaders, an impressive array of policies and institutions, and a set of active constituencies, many of which benefited from liberal policies. Thus the ideology replicated itself from generation to generation.

But, in my opinion, mid-century liberalism has been dead for 25 years. The Great Society diagnosis doesn't fit our contemporary problems, many of which have strong cultural dimensions. The leftover institutions, such as public schools and environmental agencies, are insufficiently participatory and accountable. The liberal constituency has shattered, in part because people don't have good reasons to trust the government.

The time is ripe for a revival of La Follette-style pragmatic progressivism. An open-ended, deliberative approach to politics is timely now because we don't have any impressive ideologies. (Conservatism is as dead as liberalism is). An enthusiasm for deliberation is appropriate for an era in which we have exciting new techniques and technologies for public discussion and collaboration. It's time for a new look at government agencies now that businesses and nonprofits are becoming less hierarchical and "flatter." And small-scale experimentation is appropriate given the frailties of our large public institutions. Today's charter schools, watershed restoration projects, community development corporations, and land trusts may well be our equivalents of settlement houses and lab schools.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:08 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 12, 2007

at cygyzy

I'm going to New Hampshire just for today to speak at City Year's annual conference, which is called "cygyzy" (that's Greek for "a rare alignment of celestial bodies"). City Year, a part of Americorps, is a full-time program for about 1,200 young adults--some on a college track, and some not--who work in teams on service projects. With characteristic savvy, City Year is holding cygyzy '07 in New Hampshire during the presidential primary season and has lined up Bill Clinton, Judd Gregg, Jim Lehrer, and various other luminaries as keynote speakers.

Fittingly, I'll speak to a smaller group; and I'm planning to make the following argument:

We have traditionally defined and defended programs such as City Year as "voluntary service." That seems politically smart--who's against service? Accordingly, we have justified City Year in two main ways. First, it's supposed to be a very cost-effective--in fact, downright cheap--means of providing social services, such as mentoring and camp counseling for disadvantaged kids. Second, it's supposed to benefit the City Year volunteers, who acquire leadership skills and probably gain psychological benefits, too. Looked at that way, the City Year volunteers are actually the recipients of "services"--again, at low cost.

These justifications are problematic. Maybe City Year provides cheap services, but its corps members are paid, in part with federal funds. Doesn't the taxpayer get an even better deal from completely unpaid voluntary service? The Corporation for National and Community Service, which runs Americorps, likes to note that Americans give away $152 billion in services every year by volunteering. If we are primarily interested in how much "service" Americans generate, $152 billion of free labor utterly dwarfs City Year's federal funding and renders the program rather trivial.

Likewise, the benefits to the corps members seem beside the point. They don't volunteer to gain leadership skills. They are "putting idealism to work."

So I want to make a much bigger claim for City Year. Its corps members are not engaged in voluntary service; they are citizen workers. America desperately needs citizen workers, and City Year provides a model, a training program, and a laboratory.

The word "citizen" bothers some of us because it excludes immigrants, who can obviously benefit their communities even if they aren't naturalized. At the same time, it includes George W. Bush, Bill Gates, and your local school superintendent; but we don't mean them when we think of "citizen work." Still, it's the best word I can think of for an active member of the national community, someone who has standing, dignity, and the ability to contribute simply by virtue of belonging. If you're born or naturalized in the USA, you don't have to qualify for citizenship by getting specialized training or credentials or by obtaining a special office. You are a citizen by right.

But citizens who do "citizen work" are not merely people who belong to the community. They contribute actively. They may be pursuing a whole career of public service, contributing occasionally as part of their jobs, or giving unpaid time after work. They not only provide services, but also help to define problems in discussion with other citizens. The develop and implement plans for addressing those problems.

Today, America faces grievous challenges, such as a high school dropout rate of one third, homeland security threats, and global warming.

America has never overcome any major challenge without tapping the skills, energies, and passions of millions of our citizens. Citizen work is the genius of American democracy.

But citizen work is in decline. People are substantially less likely to work on community projects or to attend meetings than they were a generation ago. This is why programs like City Year are so important: as models of a different kind of politics.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:10 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 11, 2007

is the problem with Washington's schools that we lack a state?

I'm fascinated by the Washington, DC public school system, which is educating my younger child, employing my wife, and serving the city in which I live. As reported in yesterday's Washington Post, DC ranks first among the nation's 100 largest school districts in the percentage of its funds devoted to administration (56%), and last in the percentage of funds devoted to instruction (41%). Just short of $13,000 is appropriated per child in the system--an amount that has risen rapidly as enrollments have dropped--but only $5,355 is spent on teachers, classroom equipment, and other forms of "instruction."

The educational results are equally dismaying. Of 11 major cities that collected comparable data on reading and math in 2005 (from the NAEP), DC ranked last in proficiency. We remained in last place even when comparisons were made only among poor students in those 11 cities. We were thus surpassed by several cities with bad reputations for public education, including Cleveland, Atlanta, and Chicago.

I do not understand how to tackle these problems. I think all the major ideas on the table are inadequate. (For instance, our experience with charters shows that we cannot achieve very much by enhancing competition, decentralizing control, or avoiding unions.) For today, I'll just contribute to the debate in a very modest way. Some defenders of our system argue that DC suffers from not having a state. Whatever services are provided by state agencies in other jurisdictions must be covered by the city's budget in Washington. But Maryland spends $112 million of its own funds (not federal aid) on its state education agency (source). There are about 852,920 enrolled students in Maryland schools. That means that the state spends $131 per kid per year on statewide education services. If Washington got that much help from a state education agency, it would be like increasing our schools' funding by 1.011% .

In other words, the lack of a state education agency is no excuse.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:40 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

June 8, 2007

on Providence

(Providence, RI) I don't come here very often, but I'm developing a habit of ruminating about America whenever I walk around this city's historic core. Not only did Providence play an important role in our founding, but there is something classically American about the old houses near Brown University. They were built in the same style that was current in Britain at the time--"Federalist" is just the American version of "Regency"--but their white picket fences and front lawns belong only in this country. Their classical details evoke the ideals of a young commercial republic.

(Providence, RI) I don't come here very often, but I'm developing a habit of ruminating about America whenever I walk around this city's historic core. Not only did Providence play an important role in our founding, but there is something classically American about the old houses near Brown University. They were built in the same style that was current in Britain at the time--"Federalist" is just the American version of "Regency"--but their white picket fences and front lawns belong only in this country. Their classical details evoke the ideals of a young commercial republic.

It's an ambiguous legacy. I have previously described John Brown, who built one of those fine houses and helped to found Brown University as well as the United States, and who could rightly be called "slave trader ... and patriot." It was one of his descendants, I believe, who built the John Carter Brown Library over whose ionic marble lintel is chiseled the word "Americana." As I walk, I think of two other Providence figures: Roger Williams, prophet of peace and religious toleration and founder of the city, and Ruth Simmons, the current President of Brown University. Dr. Simmons, 12th child of Texas sharecroppers, leads the institution that John Brown founded with slave money.

This time, I arrived in Providence on a Peter Pan bus that carried its share of lost souls. In the bus depot, people looked strung out. I had come from an intense conference in which many participants were alarmed and furious about the state of our democracy. Even before the conference, I had been thinking about urban America and the startling evidence of exclusion. People whose ancestors came to America as John Brown's property are now filling our state prisons literally by the million. No other country imprisons so many.

This time, I arrived in Providence on a Peter Pan bus that carried its share of lost souls. In the bus depot, people looked strung out. I had come from an intense conference in which many participants were alarmed and furious about the state of our democracy. Even before the conference, I had been thinking about urban America and the startling evidence of exclusion. People whose ancestors came to America as John Brown's property are now filling our state prisons literally by the million. No other country imprisons so many.

Yet Brown and its surroundings represent freedom and excellence. Those buildings are very fine; and quite diverse people walk among them, use their resources, and even find distinguished places within them. I feel more alienated than usual from "Americana," and that feeling is mixed with nostalgia, because once I had a less complicated relationship to the Republic and its early history. But I refuse to give up on the ideals of Roger Williams and Ruth Simmons or the beautiful communities that Americans have--sometimes--built.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:56 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 7, 2007

new CIRCLE website

(Providence, RI): I'm in this lovely city for meetings with professors who conduct community-based research. Meanwhile, CIRCLE has entered the 21st century by rebuilding our website so that it runs off a database and is no longer simply a set of hand-built html web pages. Every document that we have published is now entry in the database, and it's much easier to find things. Lacking a budget for web design, we did this with in-house staff time (thank you, colleagues) and very cheap WordPress software. WordPress was built for bloggers but is flexible. In the place of blog entries, we enter working papers, fact sheets, press releases, and the like.

Posted by peterlevine at 5:04 PM | Comments (3) | TrackBack

June 5, 2007

the power of consensus

(Portsmouth, NH) I've been in New Hampshire for a meeting to help launch something called the Democracy Imperative. The participants are a mix of professors, college administrators, and activists based outside of universities. It is fairly diverse in terms of race and ethnicity, training, and profession. I knew about 10 of the 34 participants quite well before I came, and I knew everyone at least a little by the end of the second day. There are many overlapping networks and mutual friends.

It has been an intense meeting with much positive emotion and collaborative work. By the end of the second full day, the room was covered with big sheets of handwritten notes, action steps, mission statements, concerns and hopes. As is common at such meetings, we went around the large room and asked everyone to reflect on the meeting so far, in preparation for the third and final day. One after another, people spoke of their gratitude for the gathering, their commitment to the common cause, and their enthusiasm for the process. It struck me that if any participants had been disgruntled--or even a little dissatisfied--they would have been hard pressed to express those concerns, once 10 or 20 other people had spoken in emotional and positive terms.

Even though participants are not required, paid, or otherwise rewarded for attending, they have come under intense pressure to pledge support for the group. That pressure comes from the group itself. One could view such pressure as oppressive--as the tyranny of the majority. But participants in our meeting have the option of quiet, polite exit after the conference disbands. Thus one can view consensus as a form of democratic pressure or power that elicits contributions to a collective enterprise without threats or payments. (Jenny Mansbridge's Beyond Adversary Democracy is the classic text on such power.)

Posted by peterlevine at 9:57 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

John Donne, The Ecstacy

(In Portsmouth, New Hampshire) In a review by John Carey, I came upon a strange and wonderful John Donne poem, "The Ecstacy." Here it is in the left column with my literal paraphrase to the right. (Literal interpretation seems to me a necessary first step in understanding metaphysical poetry, or any dense verse.)

THE ECSTACY |

|

WHERE, like a pillow on a bed, |

1. Two people (the narrator and a woman; see 4) who are fond of one another sit on a flowery bank. |

Our hands were firmly cemented |

2. They hold hands and look into one another's eyes. |

So to engraft our hands, as yet |

3. They unite by holding hands and visualizing the same object (possibly the propagation of the violet mentioned below: 10) |

As, 'twixt two equal armies, Fate |

4. Their souls meet in between their bodies and ... |

And whilst our souls negotiate there, |

5. negotiate (possibly about whether to have sex; see 13) while they lie still and silent for the whole day. |

If any, so by love refined, |

6. If a third person who fully understood love stood nearby, ... |

He--though he knew not which soul spake, |

7. he could benefit morally from what they say in one voice, which is: |

This ecstasy doth unperplex |

8. "This state of fusion shows us that we did not love sex or bodily motion, ... |

But as all several souls contain |

9. but the union of two souls that were never self-sufficent. |

A single violet transplant, |

10. If you replant a single flower (perhaps the violet in 1), it can grow and multiply. |

When love with one another so |

11. [Likewise,] when two souls are in love, they create one better soul. |

We then, who are this new soul, know, |

12. We are this new soul, composed of our own original souls as atoms. |

But, O alas! so long, so far, |

13. But why do we shun our bodies? |

We owe them thanks, because they thus |

14. It was through our bodily sensations that we learned to love; bodies are not superfluous but are mixed with souls into an alloy. |

On man heaven's influence works not so, |

15. Just as heaven (i.e., stars or angels) must influence us through the physical medium of air, so a soul communicates with a soul by means of the body. |

As our blood labours to beget |

16. We struggle bodily to create images that are like souls (referring either to the common thought mentioned in 3 or to conceiving a child). |

So must pure lovers' souls descend |

17. Thus we must descend from thought to our senses ... |

To our bodies turn we then, that so |

18. and appreciate one another's bodies." |

And if some lover, such as we, |

19. And if the third person stayed to watch us have sex, he would still think that we were spiritually united. |

The movement of the poem is from static bodies upward to thoughts and then back into animated bodies. At the beginning, "we" are two separate motionless physical objects (we "sat"; we "lay"). In the middle verses, "we" are one disembodied consciousness, addressing a passive third party and deciding whether to reenter our bodies. At the end, body and soul are one.

I read the poem as an argument by a male narrator to a female lover that they should have sex, because it will be like "ecstasy" (a religious "state of rapture that stupefies the body while the soul contemplates divine things"). In that case, the claim that both souls speak as one in the middle of the poem is more of a hope or a lure than a fact. There is some irony in the poem--a gap between what the narrator means and what he says, and perhaps also between how he sees himself and how we are supposed to see him. But the irony hardly cancels the sensuality of this poem that begins with pregnant swelling banks and ends with souls gone to bodies in plain view of an approving observer.

Posted by peterlevine at 6:56 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 4, 2007

portrait of the inner city

(Manchester, NH) A study by Lois M. Quinn (pdf) dramatizes the suffering of poor urban Americans in 2007--and exemplifies useful scholarship at an urban public institution. On behalf of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee's Employment and Training Institute, Quinn describes one zip code, 53206, where:

62% of the men in their early thirties are now or have been in state prisons; The number of incarcerations for "drug offenses only" has risen by 493% since 1993 (but more incarcerations are for assault than for drug offenses); Women in their 30s outnumber men by 3 to 2; Housing prices have risen by at least 50% in the last three years; The average income of tax-filers (a small proportion of the population) was $17,547; 90 percent of these individuals are single parents; Two thirds of consumer spending is outside the zip code; Ninety percent of people who declare income from working in the zip code live outside it; 56 percent of people who declare income from working in the zip code are white even though 97 percent of the residents are African American; and More than three quarters of loans to homeowners are subprime or high interest.

From Census data, we can also tell that this zip code has:

a very high ratio of children to adults;

a median household income of about $20,000 with a median of 3.1 people in each household;

housing stock that is mostly at least 55-65 years old;

almost no immigrants.

Needless to say, there are many other zip codes like Milwaukee 53206.

I am all for Asset-Based Community Development, building on indigenous resources, local leadership, and culture-change. I am suspicious that pouring in money could solve poverty by itself, because the money is usually misapplied by powerful outsiders. However, civic, participatory, grassroots strategies need to work for people in places like 53206--and quickly. That is the test of whether they are worth anything at all.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:09 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 1, 2007

touching down

I'm in the office for one of two days during a three-week spell of travel. Next week it's New England for meetings at the University of New Hampshire, Providence College, and Bryant University in Smithfield, Rhode Island. This seems to be the season for conferences and other gatherings, perhaps because you can count on academics to attend between the end of classes and their annual migration to beach houses and foreign shores. There's a pile of paperwork to attend to in the office, and we spent time this morning being fingerprinted so that we can work with adolescents. CIRCLE will be teaching a course for local kids who will choose an issue, identify adults who may have the capacity to address that concern, interview the adults about their work and about their connections with other adults, develop a "network map" of the individuals and institutions with power over their issue, and present their conclusions on a public website. We start on June 25th. I'm very much looking forward to what we'll learn and hoping that we give the kids a good experience as well.

Posted by peterlevine at 1:01 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack