« March 2007 | Main | May 2007 »

April 30, 2007

a youth preamble

I spent some of the weekend in Wisconsin with Mobilize.org, which is planning to create a "youth declaration." I couldn't draft such a document, because it should be written collaboratively by many young Americans--not by one graying Gen-Xer. However, if I were randomly selected for the Thomas Jefferson or Tom Hayden role, this is how I might begin:

We, Americans born after 1975, have earned a place in public life. We volunteer at much higher rates than our parents when they were young. We have pioneered new ways of sharing information and creating public goods, from hip-hop culture to YouTube. Forty percent of us are people of color; of all American generations so far, we are the best at working with people from diverse backgrounds. We are idealistic and concerned.

For the most part, we accept the basic principles of American society. Few of us challenge corporate capitalism, representative democracy, education, science, or the maintenance of an effective military.

Yet we charge you, the older generations of Americans, with betraying your principles:

You claim to support a market economy, yet you have borrowed eight trillion dollars in public debt that you expect us to pay back, with interest, from our salaries.

You claim to favor entrepreneurialism and competition, yet you bequeath to us crony capitalism, corporate welfare, and many forms of inherited privilege.

You claim to practice representative democracy, yet those who govern us are mostly older white men--many of them millionaires, many of them children of powerful officeholders. They do not represent us, and they do not seem accountable to us or concerned about our long-term interests.

You claim to prize education as the path to success, yet you have given us schools so flawed that one third of us do not even complete the twelfth grade.

We are already playing constructive roles and are ready for more obligations and responsibilities. But you must take us seriously. We are ready for a conversation about how we can address our country's most serious challenges.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:39 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 27, 2007

four years after the "Civic Mission of Schools"

(Wingspread, near Racine, Wisconsin) I'm here for a meeting of Mobilize.org, which is working with various partners to try to construct a declaration or manifesto on behalf of the Millennial Generation. Young Americans from across the country will have a substantial role in creating this declaration; we are talking about how to organize the process. That question raises many complex and interesting issues. My head is so full of conflicting thoughts and echoes of other people's speech that I do not feel ready to write anything here.

Instead, let me recommend the current issue of CIRCLE's newsletter (PDF here; or free copies are available by request to Dionne Williams). Four years ago, CIRCLE and Carnegie Corporation of New York published the report entitled The Civic Mission of Schools. Since then, we at CIRCLE have helped launch a lobbying campaign to fight for the report's recommendations and funded additional research to address questions that the report raised--using $1 million in research support from Carnegie. Our latest newsletter summarizes the policy changes and the new research, showing the benefits of commitment and sustained focus.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:50 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 26, 2007

Iraq: the power of words

(From the Avis car rental office at O'Hare Airport, Chicago) Here are two critical issues of terminology that affect our conduct of the Iraq war:

Whom are we fighting?

Our enemy cannot be defined as the Iraqi unsurgency. That's a disparate collection of factions that are mainly fighting one another and will continue to do so after we leave. It cannot be "terrorism," because (as many have noted) that's a method, not a cause, an organization, or a movement. "Terrorism" cannot even be defined without courting controversy. But if we are automatically at war with any entity that uses terrorist tactics (as standardly understood), then we'd better prepare for combat in countries from Ireland to Sri Lanka--of which Sudan ought to be our top priority.

I certainly hope our enemy isn't Islam, because that's one of the world's great religions, and millions of our own citizens are members. Al-Qaeda is an enemy, but it's too loosely organized and small to define our long-term problem. If Al-Qaeda were wiped out, we would still have a struggle on our hands. The word "Islamofacism" has been criticized for causing offense. By itself, that objection wouldn't necessarily bother me; but it does seem a misleading and sloppy term. Fascism, invented in Italy in the 1930s, was anticlerical, secular, regimented and militaristic, enthusiastic about engineering and mass media, and committed to social order. Osama bin Laden appears to be on the opposite side of most of those issues. We need a word that describes a particular form of reactionary, violent, antisemitic, patriarchal, authoritarian politics that draws from Sunni fundamentalism but also from reactionary European thought; that mimics clerical titles without engaging the traditional clergy; and that embraces decentralized, anarchic tactics despite its vision of a unified, hierarchical theocracy. That movement is probably not our biggest problem in Iraq, let alone the world; but it is worth fighting.

2) What should we call the inevitable US withdrawal from Iraq?

The White House wants to call it a "surrender" or a "defeat." That's a tactic to make congressional Democrats look bad for demanding an end to the combat. And perhaps the president really feels that we would win if we did not leave; thus pulling out is a "surrender." However, the White House's terminology will have terrible consequences for the country. When we do leave Iraq--as we will--calling our own departure a "surrender" will give our enemies an enormous propaganda victory. At home, it will fuel a debate about which party caused the defeat. (Was it Bush, by starting the war, or the Democrats, by ending it?) That debate will be deeply divisive, especially because Republicans and Democrats tend to be separated by geography, ethnicity, profession, and creed.

Many Democrats will be tempted to call the withdrawal the end of a fiasco or a debacle. That terminology will be tempting because it is at least partly true, plus it piles lots of blame and shame on the incumbent administration. The problems are: 1) It makes our troops' sacrifices look completely pointless and hides the competent, ethical, and courageous soldiering that has occurred. 2) It gives Republicans--including those outside the administration--no incentive to compromise and help get the troops home. And 3) It fuels the same debate noted in the previous paragraph: not necessarily to the advantage of liberals.

I would therefore be tempted to take the following line: Whether or not we should have invaded Iraq in the first place, we succeeded in removing a hateful dictator and smashing a major army halfway around the world with hardly any casualties on our side. That is a sign of enormous strength. A civil war then broke out. That conflict is morally our responsibility, because we might have been able to prevent it. In any case, we are accountable for what happens to a population whose nation we chose to invade. Nevertheless, there is very little we can do to end the civil war. We lack the necessary skills and knowledge. More important, civil conflict is just not something that can be resolved by an outside force; it must be negotiated by the parties. Possibly, if we imposed an effective martial law for many years, the factions in the Iraqi domestic conflict would run out of energy and resources. But the odds favor disastrous results even from such an enormous investment of our resources. Therefore, it is past time to leave. This is a moral failure but not a military defeat, and it is certainly not a "surrender."

Posted by peterlevine at 12:55 PM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

April 25, 2007

charter schools: where we stand

I live in a city, Washington, that is shifting to charter schools. They will enroll a majority of the public school population by 2014 if current trends continue. According to V. Dion Haynes and Theola Labbe in today's Washington Post, "D.C. charter school enrollment rose during the past five years by 9,000, to 19,733 in 55 schools, while the traditional school system closed classrooms as enrollment dropped by almost 13,000, to 55,355."

Traditional American public schools are centrally governed by local authorities that can be quite large: New York City enrolls more than one million children. Charter schools, a recent innovation, are publicly funded but self-governing (as long as they retain their "charters" from the city or state). In DC, they receive about $11,000 per pupil they enroll plus some money for facilities. I don't think any of our charter schools' teachers are unionized. Currently, seven percent of the charters in my city are meeting the standards for "adequate yearly progress" under federal law, compared to 19 percent of the city's standard public schools. Nevertheless, the charters are growing by 13 percent per year as parents move their kids to them.

On one hand:

Charters test the idea that parental choice will produce better outcomes, as a monopoly is replaced with a market. The DC charter schools may serve a harder population than the regular schools, which could partly explain their very low success rate on standardized tests. But clearly, choice is no panacea--not if only seven percent of the charters can meet standards of adequate yearly progress. Charters test the theory that too much money is wasted in the downtown bureaucracy and fails to reach the buildings where the kids are. Each charter gets a guaranteed amount of cash, yet they perform worse than the schools in the main system, which must share their funds with downtown. Charters test the proposition that teachers' unions are the problem. This may sound like a ridiculous idea to some readers (especially those who read from overseas); but there is a widespread view in the US that teachers' unions are the root cause of our failing schools. The unionized DC schools seem to perform better than the non-unionized charters.

On the other hand:

I do not object to charter schools on ideological grounds. They are public schools in the same way that schools in Western European social democracies are public--funded and licensed by the state. The fact that governance is decentralized does not make them private. In our own family's school, I think most parents would oppose becoming a charter on the grounds that we would be abandoning the public system in favor of a "market." I'd have no such objection, but would be proud to call our school "public" even if it seceded from the citywide bureaucracy.

The citywide bureaucracy frequently treats parents and teachers with disrespect, even open contempt. I strongly suspect this is one reason that people are shifting over to the charters, which are more likely to treat people politely and respectfully.

Charters give adults opportunities to work and innovate within the public sector. One would hope the results would be good, and so far they are mixed. But apart from the results, participation is arguably a right of citizenship.

Although I would not ignore test results and "adequate yearly progress," these are not the only criteria. Parents may be shifting to charter schools because of other values. I spent part of the morning looking for national survey results about what parents want for their kids. The questions that I found struck me as excessively narrow or beside the point. But everyday experience suggests that in a diverse city like Washington, people want various things for their children--values, cultural references, experiences, and supports. They may be looking for charters that match those preferences more closely than the regular schools do.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:27 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 24, 2007

celebrity culture and politics

The five "most popular" stories on CNN today are:

1. "Judd: How a $10 net can stop a killer" (actress Ashley Judd endorses anti-malaria nets.)

2. "Basinger: I didn't leak Baldwin phone message" (a domestic spat between two formerly married actors)

3. "Dern: 'Ellen' kiss put me out of work" (one actress kissing another actress causes a scandal)

4. "Commentary: The hypocrisy of repeating the 'w-word'" (about the Don Imus affair)

CNN is a news channel. The dominance of entertainers is striking, although perhaps not surprising in our era. People turn to actors, singers, and comedians for advice on serious issues--such as malaria--and for cases and controversies that can provoke debate about everyday issues. Some good may come of this, for instance, if Ashley Judd is correct about malaria nets and if people act on her advice. But there are serious dangers.

First, it seems unfair and arbitrary that physically attractive people with (some) talent for singing and acting should be able to influence social norms and political opinions. But that unfairness may be unavoidable. In a country of 300 million people, most leaders start with arbitrary advantages. It's just too hard to rise from anonymity to national leadership within a few decades of working life unless one has a leg up. That's why most of our political leaders are the children or spouses of former presidents or presidential candidates--interspersed with a few billionaires and an occasional general. It's not clear that being the son of a president and grandson of a senator is any worse of a qualification for leadership than, say, starring opposite Morgan Freeman in "High Crimes."

But I think celebrity culture is worse than merely unfair. It's pernicious because celebrities are admired for what we assume are purely individual talents and successes. In truth, movies are group productions; and actors and singers are coached and taught by others. All human achievements are at least somewhat collaborative. But stars are prized for what they say and do apparently on their own, not for leading or inspiring colleagues or sharing tasks with others.

Celebrity culture is also pernicious because everyone knows that you don't have to be ethical, wise, or well-informed to be famous. You can achieve celebrity without even the pretense of virtue if you and your talents are attractive enough. In contrast, politicians at least presume to have good ideas and high personal character. Ever since the word "politician" entered the English language, it has provoked cynicism. ("Get thee glass eyes; / And, like a scurvy politician, seem, / To see the things thou dost not." Lear, IV. 6.) But the cynicism arises because of a gap between promise and reality. Celebrities promise nothing but entertainment.

Further, celebrities are rich. They attract attention because of their consumption--their clothes, houses, and travel. Some celebrities are nothing but rich. Nonetheless, they are treated as peers of musicians and actors who might actually have talent. That indicates that central to the definition of a "celebrity" is conspicuous consumption, which is bad for nature and the soul.

Finally, the modern celebrity culture erases distinctions between public and private life. Some performers lead dignified lives out of the public eye and expect us to pay attention only to their work; some politicians and tycoons lead personal lives that fascinate the tabloid press. The problem is not that movie stars and singers have too much prominence, but rather that we treat most prominent people (regardless of their fields) like the winners of a high school popularity contest. They seem interesting because of their personal behavior, especially as it involves sex. This cannot be good for the culture. It is bad for politics if we expect our political leaders to act like celebrities.

Posted by peterlevine at 1:37 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 23, 2007

citizen liaison offices

(In Massachusetts) Colleagues and I are looking for policy ideas that would support civic participation. In 1994, in a report for the White House Domestic Policy Council, Paul Light recommended the creation of a "Citizen Liaison Office" (CLO) within each major federal agency. A CLO would review existing procedures and programs for barriers to citizen participation. It would likewise review proposed laws and regulations. Each CLO would provide training for employees of its own agency on how to work with citizens--not individual citizens, viewed as clients or constituents, but organized groups that address problems assigned to the agency. For instance, EPA collaborates effectively with communities and associations that conduct environmental monitoring. Finally, all the CLOs would meet as an inter-agency task force to share ideas and work out government-wide policies for enhancing citizens' involvement. Today, some of the most promising of such policies would take advantage of computer networks. For example, citizens could participate online in rulemaking, using one website for all agencies. They would not just submit individual comments on proposed regulations, but would participate in a "wiki"-like process that would add value.

Light asked "whether government really needs another bureaucratic unit, more paperwork, and more reports." As a true expert on the federal civil service and public administration, he concluded that the benefits of adding CLOs would be well worth the price. The same idea could be applied in local government, as recommended in 1993 by the National Commission on the State and Local Public Service.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:33 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 19, 2007

too much coverage of the Virginia Tech tragedy

The amount of coverage has been staggering--dozens of stories per day in the top national newspapers, nightly broadcast news programs that are lengthened by half an hour, 24-hour repetitions of the same information on cable news, even a blow-by-blow account in the "Kid's Post" section of the Washington Post, which my 7-year-old reads. I first found out about the Blacksburg tragedy because a student TV news crew stopped me on the street to ask my opinion. This is a global phenomenon: Le Monde and the BBC also led with Cho Seung-hui's picture when I looked.

It's a choice to devote so much space and time to those 33 deaths. Bombers killed 158 in US-occupied Baghdad on Wednesday. Nigeria, the biggest country in Africa, saw violence connected to its presidential vote. Comparisons are odious; they imply that one doesn't care about particular victims and that human lives can be counted and weighed. I do sympathize with the Blacksburg victims and their families. I sympathize because I have been told their stories in detail; but there are many other stories that I could have been told--other tragedies, or (for that matter) other narratives that are important but not tragic.

Perhaps the Virginia Tech victims deserve sympathy from all of us, but I suspect they would prefer less attention. I find it hard to see how the deserve something they don't want.

One reason to tell the Virginia Tech story in detail is to provide us with the information we might need to act as voters and members of various communities. For instance, I work at a university much like Virginia Tech and could agitate for new policies in my institution. But it is generally a bad idea to act on the basis of extremely rare events. There have been about 40 mass shootings in the USA. During the period when those crimes have occurred, something like half a billion total people have been alive in America. That means that 0.000008 percent of the population commits mass shootings. There cannot be a general circumstance that explains why someone does something so rare. The availability of weapons, mental illness, video games--none of these prevalent factors can "explain" something that in 99.999992 percent of cases does not happen. (Bayes' theorem seems relevant here, but I cannot precisely say why.)

It is foolish to use such rare events to make policy at any level--from federal laws to school rules. For instance, if lots of people carried concealed weapons, there is some chance that the next mass killer would be stopped after he had shot some of his victims. But millions of people would have to carry guns, and that would cause all kinds of other consequences. The day after the Blacksburg killings, two highly trained Secret Service officers were injured on the White House grounds because one of them accidentally discharged his gun. Imagine how many times such accidents would happen per year if most ordinary college students packed weapons in order to prevent the next Blacksburg.

The last paragraph was a rebuttal to those who want to use Cho Seung-hui as an argument for carrying concealed weapons. But it would be equally mistaken to favor gun control because it might prevent mass shootings. Maybe gun control is a good idea, but not because it would somewhat lower the probability of staggeringly rare events. Its other consequences (both positive and negative) are much more significant.

If obsessive coverage of a particular tragedy does not help us to govern ourselves or make wise policies, it does reduce our sense of security and trust. It reinforces our belief that "current events" and "public affairs" are mostly about senseless acts of violence. It plants the idea that one can become spectacularly famous by killing other people. These are not positive consequences.

It is moving that some students have started a "reach out to a loner" campaign on the Internet. They are trying to respond constructively to something that they have been told is highly important. Imagine what they might accomplish if they turned their attention to the prison population, the high-school dropout problem, or even ordinary mental illness.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:40 PM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

The November Fifth Coalition

The November Fifth Coalition has just been launched as a collaboration among several major civic organizations (with others to be added to the website very soon). November Fifth is the day after the election. We mean to say that the campaign is not a competition that will end when the votes are cast; it is part of an ongoing process by which the whole American polity governs itself.

Unless we and others intervene effectively, the 2008 campaign will follow a sadly predictable script. Candidates will present themselves as the solution to our problems and will blame our current difficulties on rival politicians. Policy ideas will all be state-centered; candidates will argue for expanding, cutting, or reorganizing the government, as if the state were the only actor. The press will treat the campaign as a horse race, as if the most important question were: Who will win? Reporters will provide some stories about "issues," but again, it will all be about the government.

Neither journalists on the campaign beat nor candidates will pay much attention to citizen-centered work, such as watershed restorations, land trusts, community planning exercises, charter schools, public arts projects, and service-learning. If they propose policies involving "citizenship," these will be rather thin: for example, they may promise to increase the number of volunteers.

Citizen-centered work is increasingly robust, diverse, and sophisticated. It is addressing increasingly serious and large-scale issues, from global warming to the reconstruction of the Gulf. The November Fifth Coalition aims to draw public attention to this movement. Candidates should stop running as potential saviors and instead explain--concretely--how they will collaborate with responsible civic groups and movements to address our real problems.

At this moment, there is not a clear mechanism by which an individual can joint November Fifth. But please email me if you are interested and I will look for ways to include you.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:23 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 18, 2007

Gonzalo's commonwealth

Gonzalo is the most virtuous character in Shakespeare's Tempest, a man "whose honor cannot / Be measured or confined" (v,1,135-6). He arrives on Prospero's island in the company of vile politicians who have organized a coup and are prepared, some of them, to kill for even more power. They mock him after he makes his speech in favor of his ideal society:

I' th' commonwealth I would by contraries

Execute all things, for no kind of traffic

Would I admit; no name of magistrate;

Letters should not be known; riches, poverty,

And use of service, none; contract, succession,

Bourn, bound of land, tilth, vineyard, none;

No use of metal, corn, or wine, or oil;

No occupation; all men idle, all

And women too, but innocent and pure;

No sovereignty --

SEBASTIAN: Yet he would be king on 't

ANTONIO: The latter end of his commonwealth forgets the beginning.

GONZALO: All things in common nature should produce

Without sweat or endeavor; treason, felony,

Sword, pike, knife, gun, or need of any engine

Would I not have; but nature should bring forth

Of its own kind all foison, all abundance,

To feed my innocent people.

SEBASTIAN: No marrying 'mong his subjects?

ANTONIO: None, man, all idle: whores and knaves.

GONZALO: I would with such perfection govern, sir,

T' excel the Golden Age. (ii,1,161ff.)

Gonzalo sounds like Rousseau--and has Rousseau's problem, acutely noted by the wicked Sebastian and Antonio in their prose interruption to his blank verse. Gonzalo would need power to create his society without power. When he says, "I would ... execute all things" he implies that he would be sovereign, yet there would be no sovereignty in his anarchistic commonwealth. He must force men to be free.

Rousseau would not be born for another century. But Gonzalo quotes another Frenchman, Montaigne, whose essay "On Savages" described Native Americans as happy and free. There were two "savage" natives on Prospero's island when he arrived (although Caliban was actually an earlier immigrant). Prospero quickly made both of them his slaves, thus acting "contrary" to Gonzalo. Also against Gonzalo's principles, Prospero demands "service," charges people with "treason" and "felony," and controls his daughter's marriage "contract" and "succession." Prospero seems to be the hero of the play, which is presented as a comedy. Yet modern readers mostly recoil at his treatment of Caliban, his paternalism toward Miranda, and his slave Ariel's obsequiousness.

Yet Prospero is the hero, I think, and Shakespeare's vision is a dark one. Gonzalo may be appealing, but he is ineffectual. He has served the usurping Duke Antonio and supported the law of that regime (see i.1,30). He does nothing to overthrow Antonio or create a Golden Age. Prospero was also originally an idealist. He shunned "temporal royalties" in favor of his library, becoming a harmless scholar (i,2,131). He wanted to "abjure" his "rough" powers, as he finally does in Act V. Unfortunately, power did not vanish in Milan because Prospero refused to exercise it. His own brother and confederates overthrew him and sent him into a dangerous exile with only his child.

Then he came to a place with no sovereignty, a desert island. He had his books. Otherwise, there was no property, no crime, no border, no master or slave. But now Prospero understood that he could not simply abjure power without putting himself in grave danger. He would have to be master or mastered. Thus he made himself dictator of his new "dukedom" until, by means of an elaborate scheme, he was able to restore justice. When he finally arranges for a lawful succession, his own story is over. "And thence retire me to my Milan, where / My every third thought shall be my grave" (v,1,378-9).

Prospero wishes to avoid ruling--as does Lear at the beginning of that play. Gonzalo describes a society without rulers--just like Lear's vision once he is out on the heath (iv,6). But Gonzalo is actually nothing but a tool of a despotic state. Prospero realizes he must use rough power to restore order and imperfect justice before he dies. Shakespeare takes that to be a happy ending.

Posted by peterlevine at 1:19 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 17, 2007

whom does a White House reporter represent?

Another person who spoke on Saturday at Penn State was David E. Sanger, the chief White House correspondent of the New York Times. After his speech, I asked him whom he thought he represented when he rode on Air Force One or sat in the White House briefing room. He replied, "You always represent your readers." I asked him who he wished his readers were. I was wondering, for instance, whether he would like to reach (and therefore "represent") a cross-section of the whole national population, if that were possible. He replied that Times readers are always going to be unusual in some respects. They have a high median level of education and tend to have especially enjoyed their own college experiences. He argued that skew was acceptable as long as everyone can get access to the Times, which is easy now via the website.

That's a plausible answer. It's better than claiming that the Times only serves the truth. Despite its slogan ("All the News that's Fit to Print"), the newspaper obviously makes choices about what stories to cover and whom to interview, based on value-judgments about what is most important. Sanger had conceded that point in earlier comments.

I can imagine a reporter saying that he represents no one, or only his employer. But that would raise questions about why he should have access to the president of the United States. I can also imagine a New York Times reporter saying that she represents "the American people." That's consistent with the Times' image as an objective source of information for any citizen (regardless of creed, region, or party) who wants to make independent decisions. I've previously quoted Adolph Ochs, who said, when he bought the Times in 1896, that he intended to "give the news, all the news, in concise and attractive form, in language that is parliamentary in good society, and give it early, if not earlier, than it can be learned through any other reliable medium; to give the news impartially, without fear or favor, regardless of any party, sect, or interest involved; to make of the columns of The New York Times a forum for the consideration of all questions of public importance, and to that end to invite intelligent discussion from all shades of opinion." That's a high ideal, and it reflects a kind of implicit contract between the whole public and the Times' reporters. That contract has come into question with recent scandals, but I don't think that tighter ethical rules would fully resolve the problem. The Times cannot represent the whole American people if the 1.1 million people who buy it are skewed by class, ideology, and region. It could struggle to make its readership nationally representative, but that would probably require a change of tone, topics, and perspective. Perhaps it is best to say, as Sanger did, that he simply represents his readers and welcomes anyone to join their company.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:26 AM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

April 15, 2007

"data-mining" financial aid records

I visited Penn State over the weekend to speak. A more interesting speaker than I was Laura McGann. She is now a professional reporter, but last year, as a journalism student, she broke the story that the US Department of Education had shared information about student loans with the FBI. Through a program code-named "Strikeback," the Bureau searched for "anomalies" in loan applications that might indicate terrorist activities. As McGann tells the story, the government lied to her on several occasions to try to keep the program secret. As soon as she succeeded in proving that "Strikeback" existed, the government closed it down. Officials may have ended the program out of embarrassment, to avoid legal scrutiny--or possibly because it would do no good to analyze loan applications once Strikeback had been revealed.

McGann is a great example of a dogged, smart, courageous, "civically engaged" student who made a difference with her work. And I have grave misgivings about the secret program that she uncovered. Mixing law enforcement with education and financial aid should ring alarm bells.

However, all the people who asked questions or made comments after McGann's talk treated "Strikeback" as a terrible scandal. I'm not quite so sure.

I can see how "mining" loan applications might actually be a useful tool for national security purposes. It would be good to know, for example, if a bunch of students who were already under some degree of suspicion all sought financial aid to attend flight schools. We could debate whether one has a reasonable expectation of privacy when disclosing information to the government, whether data-mining could have a "chilling effect" on free expression and association (even if Strikeback were kept completely secret), and what degree of individualized suspicion the government must have before it can look at a record.

To me, the main question is whether the Department of Education acted according to the terms of existing law, because governmental lawlessness is deeply troubling--and that's what we saw when the Bush Administration bypassed the FISA court to intercept messages without warrants. I'm no expert on the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), but it appears a bit ambiguous whether law enforcement agencies need subpoenas to obtain financial aid records. The law allows information to be shared, "subject to regulations of the Secretary, in connection with an emergency, [with] appropriate persons if the knowledge of such information is necessary to protect the health or safety of the student or other persons." That seems like a narrow loophole that might allow information to be shared after 9/11, albeit with a fairly tendentious definition of an "emergency."

In any case, I returned to Washington on Sunday to read that private lending companies are "mining" the same database, the National Student Loan Data System, for commercial prospects. The Department of Education apparently opposes this misuse of its data and may shut down the whole database to block it. Coincidentally, a member of my family received an invitation to participate in a federal medical study. The government could only know that she was eligible for the study if they had access to her medical records or records of her over-the-counter drugstore purchases. And indeed, the government's mailing said, "Names and addresses were obtained from a consumer information database."

All of which makes me think that our most serious problem may be the commercial use of private data, not data-mining by the FBI.

Posted by peterlevine at 2:31 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 13, 2007

beyond voting

Numerous nonprofit groups are involved in mobilizing people to vote--usually focusing on poor, young, or minority Americans, who are least likely to participate. Other organizations fight legal barriers to voting. Often their objectives are progressive: they seek greater political equality so that policies will be more just. I certainly share these objectives, but I argue that we must look beyond voting and also consider how people directly address problems at the local level. Working on PTAs, tenants’ associations, and community development corporations; restoring ecosystems; organizing anti-crime patrols; and maintaining community websites are examples of fundamental democratic work.

1) We need such local, participatory efforts to address our deepest problems in areas like education, crime, the environment, and economic development. Large governmental institutions cannot solve these problems unless there is also strong local participation.

For instance, Harvard professor Robert Putnam finds that the level of adult participation in communities correlates powerfully with high school graduation rates, SAT scores, and other indicators of educational success at the state level. "States where citizens meet, join, vote, and trust in unusual measure boast consistently higher educational performance than states where citizens are less engaged with civic and community life." Putnam finds that such engagement is "by far" a bigger correlate of educational outcomes than is spending on education, teachers’ salaries, class size, or demographics. (Robert D. Putnam, “Community-Based Social Capital and Educational Performance,” in Diane Ravitch and Joseph P. Viteritti, eds., Making Good Citizens: Education and Civil Society (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001), pp. 69-72.)

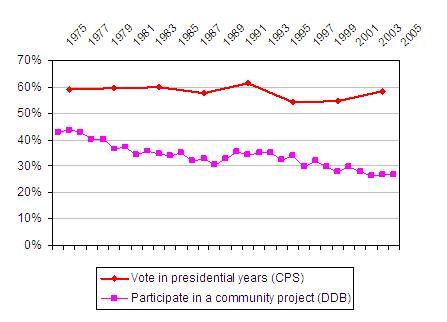

2) There are big and widening gaps in local participation by social class. Therefore, anyone concerned about equity in our democracy must worry about participation in local community work, not just voting.

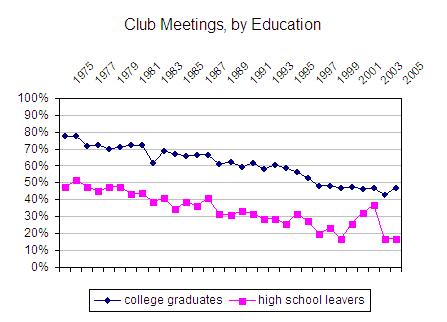

In the following graph, the dark blue line shows attendance at meetings for people with college degrees; the light blue line shows people without high school diplomas. The latter group is almost completely gone from civil society.

Put another way, half of the Americans who attend club meetings--and half of those who say they work on community projects--are college graduates today. Only 3 percent of these active citizens are high-school dropouts.

3) Voting isn’t attractive unless it emerges out of other forms of participation that give people information, confidence, motivation, and a feeling of connection to the community. People who vote are usually also members of groups and networks, community volunteers, and consumers of news media.

According to the 2000 National Election Study, there were strong positive correlations among reading the newspaper, volunteering, working on a community issue, contacting a public official; attending a community meeting; belonging to associations; and voting. To illustrate the relationships with an example: 42.4 percent of daily newspaper readers belonged to at least one association, compared to 19.4 percent of people who read no issues of a newspaper in a typical week.

4) Americans will not vote in favor of governmental programs, funded with their tax dollars, unless they believe that they can influence and collaborate with government institutions such as schools and the police. Therefore, progressives should be very eager to increase local participation.

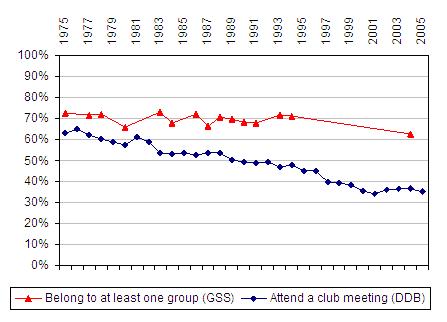

5) There has been no consistent decline in turnout since the early 1970s. (The voting rate is always too low, but it rises and falls depending on the issues of the day and the performance of major politicians.) However, there has been a consistent decline in local problem-solving and collaboration.

6) Probably one reason for the decline in face-to-face, public work at the local level is the change in the nature of our organizations. Theda Skocpol argues that non-participatory groups are replacing participatory ones. The graph below reinforces her finding. The red line shows that membership in groups is modestly down, but attending a meeting has declined much more substantially. In other words, people still join associations, but the groups they join don’t involve meetings. That means that people have less voice in civil society.

7) Despite the decline in the proportion of people involved in local problem-solving and hands-on work, this sector is very innovative and has great potential for growth. We see all kinds of successful projects, ranging from community blogs to the “21st Century Town Meetings” recently conducted in New Orleans; from youth advisory commissions to whole urban neighborhoods that have been rebuilt by church groups.

For examples and case studies, see Cynthia Gibson, Citizens at the Center (Case Foundation White Paper, Carmen Sirianni and Lewis Friedland, The Civic Renewal Movement: Community Building and Democracy in the U.S (Dayton: Kettering Foundation Press, 2005), Archon Fung and Erik Olin Wright, Deepening Democracy: Institutional Innovations in Empowered Participatory Governance, and Community-Wealth.org.If the premises presented above make sense, they imply that we need more collaboration among voting rights groups, groups that mobilize citizens to vote, and groups that promote civic innovation and collaboration at the local level. We should devote attention not only to inequalities and barriers in the formal political system, but also to other trends that may cut citizens out of public life. Two examples are the professionalization of advocacy and the excessive deference given to expertise in areas such as education, the environment, and economic development.

Finally, we need to consider policy reforms that take seriously the capacity of citizens to address problems. These reforms should go beyond thin conceptions of citizenship such as we see with the national service programs (Americorps and the like). Examples are here.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:08 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 12, 2007

academic freedom and accountability

More than a week ago, Harry Brighouse wrote a Crooked Timber post entitled "What's the point of academic freedom?" It provoked a lively, focused, and intelligent discussion. One of Harry's main points was that academic freedom is not primarily a matter of individual autonomy. Universities, disciplines, and academic departments control what is taught, what is published, what work qualifies advanced students for degrees, what research is funded, who is hired, promoted, and tenured, who is invited to speak publicly, and on what topics. In all these respects, academia as a set of institutions constrains the free speech rights of individual academics when they are on the job.

The main questions, therefore, are: (1) To what extent should academic institutions be autonomous--collectively-self governing? (The alternative is for some outside power, such as the state government, to regulate them). (2) How should academia govern itself? For example, should the faculty of a whole university (which combines many disciplines) influence tenure decisions within a particular department? (3) To what extent should academic institutions decide to govern themselves by granting maximum individual autonomy to professors over such matters as course topics? To what extent should the internal norms of academia be libertarian, as opposed to meritocratic, egalitarian, or communitarian?

Much of the discussion in the comments thread favored institutional autonomy for academia on the grounds, first, that outsiders lack the expertise to make judgments of quality, and second, that politicians and students have untrustworthy agendas. The examples that arose include medieval studies, philosophy of language, and Victorian English literature. In these cases, research costs relatively little (thus is can be sustained with tuition money). Such research has relatively little impact on public policy or public issues. And such research can be particularly technical and hard for outsiders to judge properly. Thus it seems unnecessary and unwise for outsiders, such as politicians, to try to influence how these disciplines are practiced.

But the core liberal arts represent only a small fraction of academia. Some professors are engaged in pure research that is very costly, requiring particle accelerators or massive door-to-door surveys. These researchers are surely accountable to the taxpayers or foundations who fund their work. Even if legislators cannot understand particle physics, they must make judgments about whether it is worth money that could otherwise be spent on child health or returned to taxpayers. There is no expertise on that essentially moral matter, which is for the public and its representatives to decide.

Other professors teach and study fields like elementary education, accounting, marketing, planning, forestry, law, public health, librarianship, and nursing. These fields have direct relevance to public institutions and policies. For example, planners actually determine the shape of our cities; education professors profoundly influence aspects of our public schools. Academics are also gatekeepers to licensed professions, such as law and teaching, that are very powerful within the state sector; in this respect, their political power is evident and direct.

The expertise that these professions develop is at least partly problematic. For example, it is good to have rigorous, quantitative research on education. But it is also crucial for parents and other citizens to judge what their schools are doing and why. If education becomes dominated by highly technical jargon, our schools are no longer genuinely "public." Genuinely public schools are ones in which many adults participate and influence the outcomes and norms. Participatory schools work better than others, but that is not the main point. The main point is that people have a right to shape the education of the next generation.

If one starts with the example of a philosopher of language, writing a paper in her own home after teaching classes to pay her salary, the arguments for academic autonomy are at their zenith. As one commenter writes, such "professors only answer to other professors." But if one starts with a professor of educational administration or urban planning, I think it's pretty obvious that the public has some rights of oversight and review. How exactly that should be exercised is a more complicated question.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:23 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 11, 2007

the actually engaged citizen

I basically just write about civic engagement. My wife actually engages. She's the "Laura" who appears in this front-page lead of a story in The (Washington, DC) Northwest Current. The article, by Ian Thoms, begins:

The mayor's school takeover plan colored much of the discussion at last week's District II school board forum in Cleveland Park, but it was the final question of the night that hit the issue right on the head.John Eaton Elementary parent Laura Broach asked the question that had been lurking behind most of the night's queries. Given the greatly reduced role of the board under the mayor's seemingly soon-to-be-approved legislation, why do the candidates still want the job?

The pending legislation will take budget authority away from the school board and give it to the city council, while transferring day-to-day management to the mayor. The school board will be left to decide some matters of curriculum and standards. I don't see a matter of high principle here, since the same electorate chooses all three bodies. It remains to be seen whether rearranging authority makes any difference at all; I doubt it will solve our system's problems, which are very deep. Public participation is a big part of the solution, and the local school board forum was a good example.

Posted by peterlevine at 6:52 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

April 10, 2007

the Jane Addams School

Voices of Hope is a new book by Nan Kari and Nan Skelton. It looks very handsome in its published form, richly illustrated. I read it in typescript (with no photos) in order to produce the following blurb: "Voices of Hope is an essential contribution to the debate about public education in America. Its subject, the Jane Addams School for Democracy, does not belong to the government. It is not a nonprofit corporation. It does not grant diplomas or give grades. Yet, in a profound sense, it is a 'public school,' a model of what happens when Americans of all ages and backgrounds come together voluntarily to create knowledge, understanding, and power. The spirit of Hull House and the civil rights movement’s citizenship schools is still alive in Minnesota today and deserves our careful attention."

I visited the Jane Addams School for Democracy in 2001 and returned with the goal of helping to do something similar in Maryland. (This post recalls my experience.)

Posted by peterlevine at 11:29 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 9, 2007

my home as described by Stephen Dunn

(Syracuse, NY) We're visiting my parents in the house where I grew up. It's a cottage on the top of a steep hill. The back yard leads into a large urban park: nicely landscaped with meadows and stands of cypress trees, but always somewhat dangerous. Inside, as I've noted before, there are almost 30,000 books. Wherever there are spaces over bookcases or on the stairwells, my parents have hung prints. These are mostly rather sedate works--but on the steps to the attic hangs a Kathe Kollwitz engraving of Death or the Devil dragging a mother away from her baby. The furniture in the living room was once upholstered in white leather.

All this is background to a poem that Stephen Dunn wrote when his family rented the house from us. I think this must have been 1973-4, when Dunn was a visiting professor at Syracuse University and we were in London. The poem, typed on a real typewriter that bit into the paper, reads:

Letter to a Distant Landlord

This is the 20th century and you

are invisible, across the Atlantic,

beyond reach. We sleep in your bed,

we make love where

you made love and it's strange

we've not met.

This house, though, does speak

of you; all the books, the good

junk in the attic, that

startling print in the upstairs hall.

You've brought the past forward

to mingle like a fine, old grandfather

with the appliances and dust.

And we approve.

Even the ghosts here are intelligent.

They wait til the children are asleep

then sit in the white chairs

in the livingroom. Some nights

it's Nietzsche, last night it was

Marx. They are all timbre

and smoke, all they want is

for me to get off my ass, to break

my spririt's sleep.

But they don't insist. They've seen

so much their rancor has turned

to sighs. We do not learn

is what they've learned.

Yet we are comfortable in your house.

It is what we wanted.

The park nearby is beautiful

and dangerous, a 20th century park,

the kind we must walk through. Our small

belligerent dog picks fights there

with Shepherds. They pick fights with him.

Sometimes though they're all tails and tongues,

like us, and the air smells good

and the grass is freshly cut.

And so we send our checks

and try to imagine your hands,

your face, the way you discuss

the things you must discuss.

Some day after you're back,

smelling our smells and rearranging

your lives, maybe we'll appear

at your door disguised as ourselves.

We'll say we're looking for a house

(that'll be our only hint), sneak

the glimpses we want, and move on

like strangers who brushed by

on their way somewhere else

and don't know why, in this century,

they cannot stop.

I love this poem as an evocation of my home, Dunn's private life, and the 20th century. I'd only quarrel with one aspect (and even on this point I grant Dunn his license). I doubt that the ghosts in our house talk about Nieztsche and Marx very often. There are shelves of books by those authors that might conjure their spirits once in a while, but I'm sure they don't reign over the house. The local spirits are English, bewigged, dusty, and interested in facts rather than theories.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:13 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

April 6, 2007

the Clean Air Act and democracy

I am certain that global warming is a serious problem. By regulating carbon dioxide emissions, the Environmental Protection Agency may ameliorate the damage a bit. However, I don't dismiss the arguments of the dissenting conservative justices in the recent global warming decision, Massachusetts v. EPA.

A responsible blog post would be based on my careful reading of the majority opinion and the dissents, relevant portions of the Clean Air Act, the best current commentaries, and a famous law review article by Cass Sunstein about the Clean Air Act (Michigan Law Review, 1999). Despite good intentions, I can see that I'm not going to pull that off. Instead, here is a simplified argument:

1) Major decisions in a democracy should be made by the elected branches of government. Legislatures are accountable, they are deliberative, they can balance costs and benefits across the whole federal budget, and they can choose among all constitutional remedies to a problem. For example, to address global warming, Congress could enact carbon taxes, import/export taxes, cap-and-trade regimes, tax credits, or regulations on producers or consumers.

2) However, Congress has a tendency to duck the tough decisions by writing deliberately vague statutes. For example, I am aware of a section of the Clean Air Act that empowers the EPA to set ambient air quality standards at levels "requisite to protect the public health" with "an adequate margin of safety." No amount of air pollution has zero potential impact on safety or health. "Adequate" safety means some amount of risk that's greater than zero--but not too much. That's not a scientific or technical judgment; it's a value-judgment about what level of safety is worth the cost. Congress avoids making such value-judgments, because then it would be responsible when some people suffer--or even die--from whatever pollution is left in the air. Congress would also be directly responsible for the financial cost of any regulation. Instead, it passes the responsibility to EPA, which can then be blamed for both the costs of a regulation and the environmental harms that are left over. Unfortunately, EPA lacks democratic legitimacy, and it can only regulate (not tax or take other actions). Regulation may be a highly inefficient response to global warming.

3) When the EPA or other regulatory agencies fail to deliver adequate policy, it is tempting to sue them. But then a court's judgment substitutes for that of a legislature. Courts lack democratic legitimacy, expertise, and the ability to impose such policies as taxes or cap-and-trade systems. They are set up to hear cases and controversies between parties; they are not good at balancing one person's interests against the common good. For example, they are not responsible for the overall budget, so they cannot decide whether a decision that has costs to the government is worthwhile, all things considered.

Thus the only really satisfactory solution is for Congress to pass laws on global warming. Massachusetts v EPA will actually be counterproductive if it lets Congress off the hook or allows Congress to delay.

Jamison Colburn argues that the case is not very significant, anyway. "What it comes down to is this: if EPA is going to refuse to regulate greenhouse gas emissions as 'air pollutants' under the Clean Air Act, and it chooses to do so in some discrete 'agency action,' it must do so on better grounds than the (lame) argument that the statute wasn’t enacted with the specific intent to regulate greenhouse gases or similar calamities. That is all it comes to, though." If Colburn is correct, then populist/democratic concerns about judicial activism are misplaced--but only because the court didn't do much at all.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:37 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 5, 2007

the money primary

This is a politically neutral blog, and indeed my vote is still up for grabs. However, I'd reflect on the big political news of the week--the fundraising figures--as follows. First, I believe that Senator Obama has struck a chord by promising a different kind of relationship between citizens and the government. He doesn't promise to solve problems (which is almost always impossible for governments to do), but he proposes to collaborate with the American people, who are in a serious mood and are capable of working constructively together. Most political "professionals" (reporters, consultants, and others) cannot understand the deep appeal of this message. It reshuffles the political deck.

Second, hundreds of thousands of Americans made small contributions, and that is evidence that social networking sites and other technologies have dispersed power somewhat, at least compared to 20 years ago. That's a good thing.

Third, however, it is a great pity that we have a "money primary." It's actually a double shame. It's obviously unfortunate that money counts so much--and despite the small contributions, the median donor is surely quite wealthy. It's also unfortunate that reporters feel they must cover matters like fundraising so intensively. They do so because they know that candidates who raise unexpectedly large amounts of cash have (all else being equal) greater chances of winning. I often quote CNN's political director, Mark Hannon, who said in 1996 that his network conducted daily polls because they "happen to be the most authoritative way to answer the most basic question about the election, which is who is going to win." The same assumption explains why reporters cover fundraising. But who will win is not the most basic question--not for a citizen. The most basic question for a citizen is: How are we going to address problems? A subsidiary question is: Which candidate should I vote for to help address our problems? It's irrelevant who is most likely to win--although the press sometimes makes it quixotic to vote for candidates who are behind in the horse race.

It's worth imagining a democracy in which people had quick access to the names and employers of all political donors--so that they could hunt for influence and corruption--but reporters were so busy covering issues and citizen's work that they didn't bother to mention the fundraising totals.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:28 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

April 4, 2007

writing and social change

(Written after a long coalition meeting in Washington.) A few weeks ago, a family friend who teaches in the humanities at a large state university said, "I hear you've been writing about how everything I do is wrong." That's an exaggeration. It's true that I'm not fully comfortable with the way we organize higher education. I'm not sure that big lecture classes are satisfactory opportunities for education, nor that we select and sort our students fairly. When I observe a lack of motivation and attention among college students, I blame it on the overall educational system, not on their character or on the professor's skills as a communicator. Thus I'd argue that institutions should change--but I would never say that it's a waste to lecture in the liberal arts.

What sticks with me, however, is not the summary of my views, but the key verb: "writing." Professors ask each other, "What are you writing on?" Or (meaning the same thing), "What do you work on?"

I do write. This blog may be evidence that I type too much. I'll admit to a case of cacoethes scribendi. But I would be unsatisfied if my only way of addressing a problem were to read and write about it. I don't think you can learn enough about a social or institutional issue by reading; you must also listen, negotiate, observe, and experiment. By the same token, writing doesn't make things happen. Books and articles can help to change opinions. They can certainly guide activists by analyzing complex problems. But they very rarely have an impact by themselves. If I wrote about what's wrong with education, but could never help to organize a response, I'd be frustrated.

Posted by peterlevine at 5:19 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 3, 2007

public participation in planning: lessons from New Orleans

Abigail Williamson, a graduate student at Harvard, has written a study of public participation on the Unified New Orleans Plan (pdf). Here I assume that her narrative is accurate and comprehensive; I use it as the basis for some thoughts about civic engagement and planning.

According to Williamson, there have been three main planning efforts in New Orleans since the hurricane. The first was called "Bring New Orleans Back" (BNOB). It was ordered by the Mayor and run by local experts and leaders--an elite. It has been praised for its technical excellence, but it became highly controversial because it rejected rebuilding some of the flooded neighborhoods that were poor and largely Black. Because it was controversial and lacked political legitimacy, the Mayor distanced himself from it, and it died.

The second planning process was run by a firm called Lambert Advisory. Williamson's interviewees told her that Lambert's process truly reflected input from diverse citizens; but the resulting plan was not satisfactory. (I'm not sure exactly how it failed to measure up.)

The third planning process was designed to be broadly inclusive and technically satisfactory. It started off with some failed public meetings, but then AmericaSpeaks was brought in to organize demographically representative, deliberative sessions involving hundreds of people at once. In the interests of disclosure, I must note that I am a member of AmericaSpeaks' board. But Williamson's study was independently funded and she finds that the meetings truly were representative, substantive, and constructive. One observer recalls:

More than anything, I think the thing I was most impressed with about Community Congress II, in addition to just the sheer numbers they were able to reach, when I went and I walked around, I saw people sitting at tables together of different socioeconomic backgrounds, different parts of town, having healthy discussions. Not necessarily always agreeing, but actually having conversations. Not just rhetoric, not yelling and screaming, but really just having healthy conversations about what they saw as the issue here.

The resulting plan appears to have legitimacy--meaning not that it is necessarily just or smart, but that people believe it arose from a legitimate process. Just for that reason, it appears likely to pass.

This is a major achievement, and it would have been impossible without demographic representativeness and high-profile, large-scale, public events. These events took skill and commitment to pull off. Those are conclusions to emphasize and celebrate. Nevertheless, I'd like to point out some limitations and challenges:

1. Framing the deliberation is tricky. If citizens are asked to produce a truly comprehensive plan (with a map and a detailed budget), then they will essentially govern the city. But no one has elected them, nor will the political leaders yield without a fight. If, on the other hand, citizens generate a plan without details, then they can avoid tradeoffs; and in that case, they aren't really deliberating. Likewise, if citizens are told to work within very "realistic" constraints, they cannot demand justice. For example, if they are told that there is only $x of state money available, they are blocked from saying that the state should be more generous. If, on the other hand, citizens deliberate without constraints, they can invent unrealistic scenarios.

2. A process like this could be manipulated to get results that someone wants. The organizers could manipulate it, or an outside group could get its own people into the meetings. In other words, the legitimacy could be false. I'm committed to AmericaSpeaks and will vouch for this particular process. But the more such deliberations are used to make important decisions, the more people will try to manipulate them.

3. The organizers had to make a prior decision about the definition of "the people." They chose the population that had lived in New Orleans prior to Katrina. Consequently, they aimed for a demographic mix that looked like the traditional city, not like the city today; and they organized town meetings in major diaspora cities from Houston to Atlanta. They could have chosen a different benchmark--current residents, or residents of the whole state, to name two examples. This is essentially a question of values, and it cannot itself be deliberated.

4. Planning is work. That's what was evident at the tables during the Town Meetings--not just talk, but work. However, planning is only one aspect of public work. Buildings must be built, trees must be planted, money must be raised, newsletters must be written, and so on. It's important for this work, not merely the talk, to be democratic and participatory.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:38 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 2, 2007

on mannerism and modernism

Over the weekend, I spent some time in the El Greco room of the National Gallery, Washington, which holds the finest collection of his work outside Spain. The National Gallery wisely hangs El Greco alongside Tintoretto, an artist 23 years his senior who was a direct influence. Both painters depict figures elongated beyond realism. They hide the backgrounds or otherwise pull their subjects out of three-dimensional space onto the plane of the picture. They leave their brushwork visible; they choose unearthly colors; and they draw attention to their own tortured emotions.

El Greco was an idiosyncratic artist, unique among Western masters because of his training in Crete. But he was not a madman, a visionary outsider, or a modernist trapped in a sixteenth-century body. He won major commissions and had a successful career because he belonged to a recognizable movement. Called "Mannerism" only in modern times, this movement encompassed Pontormo (1494-1557), Rosso Fiorentino (1494-1540), Parmigianino (1503-1540), and Bronzino (1503-1572) as well as Tintoretto (1518-1594) and El Greco (1541-1614)--the last in the line.

Mannerism is derived from the Italian "maniera," which means "style." All Mannerists had idiosyncratic styles (albeit with some similarities), and they all drew attention to style as an issue. Seeing elongated forms, wild colors, and visible brushwork, you had to know that you were looking at a work of art, created by an individual with his own techniques and values. You couldn't forget the artist and see only the subject.

Why was that approach popular? It arose in a troubled and disillusioning time, marked by religious wars, the Sack of Rome (1527), profound skepticism about traditional beliefs, and political assassinations. Disturbing images fit the age. But I also think that the logic of aesthetic development led to Mannerism.

Up until about 1520, Renaissance artists had tried to answer certain questions that seemed objective or "given." How should one represent a beautiful human body inside a room? How should one depict a scene involving several figures, such as a Madonna and Child? How should one reconstruct ancient art, especially as it was described in classical books? To these questions, a Raphael or a Leonardo was a fully satisfactory answer. Once these masters had painted their works, the only choices were to imitate them or to try something different. But the very idea of deliberately doing something different raised the question of style. It made the subjective intentions of the artist, his originality, his mental state, and the physical object he created interesting.

Exactly the same logic is evident in modernism, which explains why early modernists loved El Greco. But there was a big difference. Mannerism soon yielded to large-scale, durable movements, starting with the baroque. Baroque artists, like their renaissance predecessors, struggled to address questions that seemed "given" or inevitable. How to depict dramatic human interactions? How to show non-ideal human beings in a beautiful way? How to show wild landscapes with only small human figures, or no people at all? How to paint indoor scenes lit by fire? How to recreate the actual ancient art of The Laocoon?

For modernists, there are no objective aesthetic questions. We now think that the artists of other times and places struggled to address issues that seemed inevitable, but these questions were actually relative to the local cultures. It is possible to understand a medieval artist who has a simple understanding of perspective--or a baroque artist who views the world as a stage. But it is impossible to be like them: to address a question that seems intrinsic to art. Instead, everyone is a mannerist today. Every artist develops a maniera of his or her own and creates works that appear, first, as art objects; second, as products of a particular artist, and last (if at all) as representations of something.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:59 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack