« December 2005 | Main | February 2006 »

January 31, 2006

on culture and poverty

"The central conservative truth," Senator Moynihan famously wrote, "is that it is culture, not politics, that determines the success of a society. The central liberal truth is that politics can change a culture and save it from itself."

This is the great issue of the present, or so it seems to me. But there are more positions than Mohnihan’s liberalism and conservatism. In fact, we can classify responses along three axes. First, materialists believe that to succeed and to be happy, you need money--or things that money can buy. Their opponents are cultural determinists who believe that what matters is the "fit" between a person's norms, habits, and beliefs (on one hand) and the dominant culture of modern capitalism (on the other). A second axis runs from love for this dominant corporate culture to hatred of it. The third axis runs from those who think that government is helpful to those who consider it incompetent or corrupt.

When there are three axes, there are eight pure positions available, along with various moderate views. I think the following combinations are particularly serious and influential today:

Materialist left-liberalism: This is the view that poor people mainly need money (or its equivalent) to get ahead. They should get financial help from the state. However, no one should try to manipulate their values or beliefs.

Materialist libertarianism:: Everyone would prosper (to the maximum extent possible) if it weren’t for state institutions and regulations that distort choices, block exchanges, and forcibly educate people in bad habits and beliefs.

Left cultural criticism: What determines success is the fit between a person’s culture and the dominant, white collar, market system, with its demands for discipline and rationality. However, that system is wickedly imperialistic and dehumanizing. Capitalism, not working class and traditional cultures, must be changed.

Moynihan-style neoliberalism: What keeps some poor people poor is a set of habits and values that don't prepare them well for a competitive market economy. However, the state can and should make them more competitive. For instance, if some parents don't read to their preschoolers, then four year-olds should be in Head Start. If some households and neighborhoods impart anti-intellectual lessons, then we should lengthen the school day and year and toughen academic curricula.

Cultural conservatism: What keeps some people poor are their habits and values, but the state is bad at changing cultures. In fact, it tends to reinforce the worst cultural traits among the poor. It would be better to reduce state influence on values. For example, more students should attend religious schools.

I have no answers, but I suspect that: (1) Some degree of materialism is still important. For instance, people would be better off if they had affordable or free health insurance. (2) Nevertheless, there is a conflict between many subcultures and the dominant, corporate-capitalist world. That conflict means that no amount of redistribution will end poverty. While the redistributive programs of the twentieth century (Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid) are valuable, they leave cultural problems unresolved. (3) The record of the state in changing values and habits is neither excellent nor awful, but mixed. There have been successful initiatives, e.g., Quontum Opportunities Program, which cut dropout rates in half. There have also been numerous failures.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:28 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

January 30, 2006

love where you are

In Fort Worth last Friday, I spoke about the importance of civic engagement. I was followed by a series of local officials (the superintendent of schools, the public safety commissioner, a county commissioner, a former mayor, and others), who analyzed the main issues on their city’s agenda.

In my speech, I claimed that public engagement has declined for various reasons, including the rise of professional management and the lack of incentives to prepare young people to be capable citizens. A large proportion of the audience was young, so I ended with some arguments in favor of participating. For instance, I mentioned the intrinsic satisfaction of work on public problems. I ended by saying that you should always love where you are.

I explained that I couldn’t give any specific reasons to love Fort Worth or North Texas, because I’d only been there for 12 hours; but every place where human beings live can be loved. Every place has assets, history, and interesting complexity. To miss the place where you live is a great waste. Further, to love it means to explore it, to study it, and to work to improve it. This turned out to be a good way to conclude, because three or four of the subsequent speakers picked up my challenge and explained why one should love their city. (Incidentally, Dallas/Fort Worth--love it or not--is expected to double in size and become the megalopolis of the southern great plains.)

Posted by peterlevine at 9:37 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

January 27, 2006

cliches of civic engagement

I'm on my way to Texas Christian University in Fort Worth, where I'll be speaking about--what else?--youth civic engagement. I'm happy to support the launch of TCU's Center for Civic Literacy.

I hope that my speech does not sound like this article by Douglas Brinkley from 1994, entitled "Educating the Generation Called 'X.'" The links are to Cosma Shazili's commentary:

But all in all, to paraphrase Gertrude Stein, a "young person is a young person is a young person." They are essentially no different from their predecessors; they simply want to be regarded as individuals. By 1988, those born between 1961 and 1981 will comprise the largest voting bloc ever in American history, numbering 80 million strong. They will soon step up to the plate to try to clean up the mess. Their teacher should strive to do what education has traditionally done for the young: Bring out their best, encourage hope and nourish their imaginations.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:29 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

January 26, 2006

talking about "social justice" in education

In conversations about civic education, service-learning, and youth civic engagement, people often ask whether the purpose of what we're doing is "social justice." Lately I've been responding as follows:

1. The phrase social justice (which has roots in Catholic thought) has been claimed by the Left. In politics, phrases are often seized by one side or the other--occasionally, they even switch their valence over time. At the moment, "social justice" has a lefty ring. Therefore, there will be a predictable consequence if you say that your service-learning program or civics class "promotes social justice." You will attract leftish students, and perhaps alienate conservatives. If you speak on behalf of a public school or state university, I think you should avoid that outcome. Individual adults who work with young people are free to promote ideologies; but state institutions should be leery of doing so.

2. Although the left has claimed the phrase "social justice," true conservatives seek social justice. They just define it somewhat differently, they endorse alternative strategies for obtaining it, and they tend to call it by other names. It's important that the students who sign up for service-learning be exposed to serious conservative arguments about justice. One of the risks of using the phrase "social justice" is to narrow the range of debate about justice by keeping conservatives out from the beginning.

I often hear a (probably apocryphal) story about a student who so enjoys volunteering in a soup kitchen that he blurts out, "I hope this place still exists when my kids come along, so that they can serve, too." The standard rejoinder is that the student should investigate the "root causes" of hunger and advocate solutions.

True, but the root causes may not necessarily be capitalism or discrimination, and the best solutions may not include Food Stamps or a higher minimum wage. I'd like to see students grapple with root causes but be challenged to consider whether government intervention is the basic problem and freer markets could help. That's not usually my own view, but it's educational to consider it.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:03 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

January 25, 2006

the sincerest form of flattery

So, I'm ego-surfing as usual, and what do I come across? A term paper about an article (pdf) that I wrote--for sale at $31.95. The summary and excerpt of the term paper are poorly written and highly inaccurate. Can I sue? Should I write a better paper about myself and sell it? If a wildly inaccurate summary of my article is worth $31.95 on the open market, can I start selling the actual article for, say, $40? (Right now, it's free.) Should I be offended that people are willing to pay $31.95 not to have to read and write about my article? Does a plagiarized term paper count as a citation of my work? Why does my own article rank lower on Google than a site that sells a lousy term paper about it?

Posted by peterlevine at 7:29 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

January 24, 2006

overcoming polarization?

Dan Yankelovich (chairman and co-founder of Public Agenda) has published a new book on polarization, which is excerpted online. The excerpt argues that Americans aren't all that deeply divided between liberals and conservatives. According to Yankelovich's polls, we Americans share eleven "core values that blend traditional and progressive attitudes into a new social morality." This social morality is "centrist"; "both liberals and conservatives have something positive to contribute."

However, look at the list:

Patriotism Self-confidence Individualism Belief in hard work and productivity Religious beliefs Child-centeredness Community and charity Pragmatism and compromise Acceptance of diversity Cooperation with other countries Hunger for common ground

To me, the first seven items look basically conservative. I don't see "equity," "peace," "freedom from want," "saving nature," "civil liberties," or "fairness" on the list. The American majority prefers patriotism, individualism, faith, and family. However, as the last four items show, they'd rather not fight about such matters. They dislike sharp disagreement (that's well documented in other studies), preferring compromise, acceptance, and cooperation. Thus, while their own views are conservative, they're hoping that everyone will agree to some practical, "common-sense" ideas.

I wish the list of core values were somewhat different, although I suspect it's an accurate picture of public opinion. "Acceptance of diversity" and "child-centeredness" are the most promising items for progressives. As we know, Americans support spending for education and some diversity in corporate employment and the media. However, those beliefs are perfectly consistent with mainstream modern conservatism.

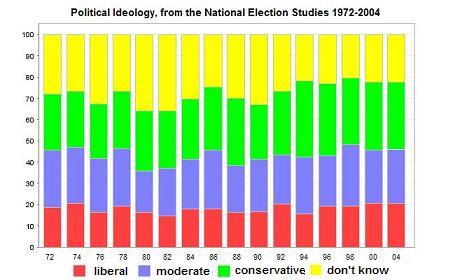

Despite the majority's hope for "common ground," the conservative 25-30% of the population actually disagrees pretty sharply with the liberal 17-20%. The middle holds the balance. They are the ones who most consistently endorse Yankelovich's eleven "core values." While they may identify themselves as moderates, I would call them conservatives without an angry edge.

[Note: This is my graph, not Yankelovich's.]

Posted by peterlevine at 12:01 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

January 23, 2006

opportunity for youth work in New Orleans

"Common Cents is offering grants up to $20,000 for projects that will contribute to an inclusive and just recovery from Hurricane Katrina. Preference will be given to service or advocacy projects that either involve young people meaningfully in the recovery, or that address the specific needs of children and youth. ... All winners will ...

Receive up to $20,000 in cash awards Showcase their project at a student conference in New York City in May 2006

"Preference will be given for projects that ...

Increase youth decision-making in the recovery and rebuilding

Build relationships between people within and outside the region

Strengthen infrastructure for sustainable services for young people

Contribute to our understanding of youth as a resource for recovery

... DEADLINE: FEBRUARY 1"

Posted by peterlevine at 1:41 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

January 20, 2006

journalists still matter

I've come from Ohio to New York City for a meeting on "Media and Communications at the Crossroads: The Role of Scholarship for Media Justice and Reform." At the meeting, my friend Lew Friedland just argued that daily news journalism is still essential to the "media ecology." I'd put the argument as follows:

It's true that people get news, ideas, and values from their family and friends and from multiple electronic sources, including the web portals of Yahoo and other Internet-service providers (which are regular news sources for 15% of young people); comedy TV (a regular source for 21% of youth); and talk radio (16%). (See this Pew Research Center poll.) However, Yahoo's headlines simply come from wire services--hence, from reporters. Comedy writers get most of their material from daily newspapers. Friedland estimates that 90% of the news stories on local TV come from a local newspaper. Debates in the blogosphere are very often triggered by reported news. Fictional programs like "Law and Order" are inspired by print journalism. Therefore, influential conversations in the kitchen, the office water-cooler, and church often derive ultimately from a newspaper.

If this is right, then we cannot consider citizen media and other new means of communication and discussion in isolation. They are dependent on the state of conventional, professional journalism--which isn't good. Newspapers are highly profitable but are cutting their staff and budgets for reporting. Two thirds of national journalists believe that bottom-line pressure is hurting news coverage--causing the press to avoid complex issues, to be sloppy, and to be timid. (Source.) Bloggers can complain about newspaper journalists from various angles; they can't replace them.

Posted by peterlevine at 1:00 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

January 19, 2006

so which is it?

1. From Matthew A. Crenson and Benjamin Ginsberg, Downsizing Democracy: How America Sidelined its Citizens and Privatized its Public (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003), p. 236:

Contemporary elites have found that they need not engage in the arduous task of building a popular constituency. Public interest groups and environmental groups have large mailing lists but few active members; civil rights groups field more attorneys than protestors; and national political parties activitate a familiar few rather than risk mobilizing anonynmous millions.

2. From Thomas L. Friedman, "It's a Flat World, After All," The New York Times, April 3, 2005:

No, not everyone has access yet to this platform,* but it is open now to more people in more places on more days than anything like it in history. Wherever you look today--whether it is the world of journalism, with bloggers bringing down Dan Rather; the world of software, with the Linux code writers working in online forums for free to challenge Microsoft; or the world of business, where Indian and Chinese innovators are competing against and working with some of of the most advanced Western multinationals--hierarchies are being flattened and value is being created less and less within vertical silos and more and more through horizontal collaboration within companies, between companies and among individuals.

*The referent here is not precisely clear, but "this platform" roughly means: the Internet and the global information marketplace.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:20 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

January 18, 2006

another week, another Miami

Today I'll travel to Miami University in Oxford, OH, having been in that other Miami not more than 10 days ago. While I was in the Big Miami, during a break, I managed to ride a city bus over to South Beach. Uncomfortably warm in my dark suit and business shoes, I walked on the sand with the art deco pastel buildings on one side and the hazy Atlantic on the other. I drank a cappuccino in a beachfront restaurant where all of the staff spoke Italian and the young guy at the next table quickly downed three bloody marys. It was 10 am.

In contrast, the last time I visited Miami of Ohio, the weather was freezing--close to or below zero fahrenheit and with a high, dry wind. However, Miami of Ohio is a picture-perfect Midwestern community with white picket fences, Christmas lights, and kids in varsity jackets. If I had to choose, I'd pick the Miami of the Midwest (the original one, as the residents will eagerly tell you).

Posted by peterlevine at 7:00 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

January 17, 2006

David Friedman on education

David Friedman has contributed some thoughtful comments on my post about political socialization and libertarianism. I had written that libertarians need most people to prize freedom; otherwise, liberty itself will weaken. However, parents want their children to gain marketable skills above all else. They therefore do not demand that schools impart public goods, of which the love of liberty is an important example. If parents do not put pressure on schools to teach freedom, then libertarians must consider other ways to educate all children for liberty. The vehicle that comes first to my mind is universal, taxpayer funded k-12 schooling with a "civics" mandate; but there may be alternatives. In arguing for civic education that emphasizes liberty, libertarians should invoke their own philosophical ideals, but they should be willing to swallow the restriction on individual freedom that will come from universal education.

Friedman replies:

I think parents are mostly interested in educating their children to have successful lives. One way of doing that is by learning what the world is like. If libertarians are correct in believing that more freedom results in a more attractive society, a more accurate picture of the world will tend to result in more support for liberty. So shifting control over schooling in the direction of parents rather than school officials and politicians is likely to result in some shift in favor of liberty.

I'm struck by the idealism of this paragraph--or, to put it another way, by the avoidance of a rational-choice framework. If individual parents want their own children to "lead successful lives" in our society, then they should hope that their kids are not too eccentric or unruly. They should try to give their children skills that are valued in the economy, along with a healthy respect for authority. That's what pays. One representative "New Jersey mother" in a focus group told Public Agenda: "There are key points--hard work, discipline, respect. If those are taught in the home, that's more than 50 percent of what you need to succeed. Even a below average kid will do well if his parents teach him that."

Libertarians believe that a better society would be more free than ours is. Even granting that libertarians are right, parents who want their own kids to be successful in today's society will hope that other parents' children fight for liberty. That fight is likely to be lonely, under-paid, frustrating, and only enjoyable if one truly prizes intellectual debate.

In an essay that's online, Friedman summarizes the position that I have adopted:

In a private system [of education], children will be taught what their parents want them to know. In a government system, children will be taught what the state wants them to know. So the government system provides an opportunity for the state to indoctrinate children in beliefs that it is not in their interest, or their parents' interest, for them to hold. Insofar as some virtues require one to act against one's own interest--for instance, by not stealing something even when nobody is watching--that is an opportunity to indoctrinate children in virtue.

I would also say that schools can "indoctrinate" children in the love for liberty. However, Friedman continues ...

One good reply to this argument was made by William Godwin, who, in 1796, expressed his hope "that mankind will never have to learn so important a lesson through so corrupt a channel." To put the argument in more modern language, government schooling does indeed provide the state with an opportunity to indoctrinate children--but there is no good reason to believe that it will be in the interest of the state to indoctrinate them in beliefs that it is in the interest of the rest of us for them to hold. Many modern societies have strong legal rules designed to keep the state from controlling what people believe--the first amendment to the U.S. constitution being a notable example. It seems odd to combine them with a set of institutions justified as doing the precise opposite.In an interesting recent article, John Lott explores the question of why schooling is controlled by the state in modern societies. His conclusion is that government schooling is a mechanism by which the state lowers the cost of controlling the population.

Obviously, there is a danger that state schools will indoctrinate in favor of the state, as Friedman fears. However, it is a simplistic theory of "the state" that understands it as a unitary, disciplined, and self-interested agent. On the contrary, public schools in the United States are highly subject to local political pressure, especially from taxpaying parents. I don't know how to prove this, but I strongly suspect that American schools teach a mix of libertarian, authoritarian, and majoritarian principles because those are the values that most parents demand. Libertarians are entitled to argue for a different list of values, one headed by individual liberty. If they can't win that argument, then I don't see how they can prevail at all.

Posted by peterlevine at 6:04 PM | Comments (6) | TrackBack

January 16, 2006

an exercise for Martin Luther King Day

I find it useful to teach WALKER v. CITY OF BIRMINGHAM, 388 U.S. 307 (1967) as an example of legal and moral reasoning. This is the case that originated with the arrest of Martin Luther King and 52 others in Birmingham, AL, at Easter, 1962. It is a rich example for exploring the rule of law, civil disobedience, religion versus secular law, procedures versus justice, and even the way that our moral conclusions follow from how we choose to tell stories.

By way of background:

In 1962, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) hoped to generate massive protests in Birmingham before the end of the term of Eugene 'Bull' Connor, the violently racist Commissioner of Public Safety. As the protests began, Connor obtained a state-court injunction against the marchers. When the SCLC leaders received the injunction on April 11, they stated, "we cannot in good conscience obey" it. King called it a "pseudo" law which promotes "raw tyranny under the guise of maintaining law and order."

At this point, the Direct Action campaign is in crisis: there have been only 150 arrests so far, and no more bail credit is available. On April 12 (Good Friday), Norman Amaker, an NAACP lawyer, says that the injunction is unconstitutional, but breaking it will result in jail time. King disappears from a tense conference, reappears in jeans. "I don't know what will happen ... But I have to make a faith act. ... If we obey this injunction, we are out of business." Leads 1,000 marchers; he and 52 are arrested. He is sent to solitary confinement. In NYC, Harry Belafonte raises $50,000 for bail. The New York Times and President Kennedy condemn marches as ill-timed.

April 15 (Easter Sunday): MLK is released from solitary confinement, still in jail. Writes "Letter from a Birmingham Jail."

April 26: King is sentenced to five days with a warning not to protest. Sentence is held in abeyance.

May 2: Children's march. King: “We subpoena the conscience of the nation to the judgment seat of morality."

May 20: Supreme Court strikes down Birmingham's segregation ordinances. A deal is worked out.

September: bomb kills four little girls at Birmingham's Sixteenth Street Baptist Church.

SCLC appeals King's conviction for two reasons: to overturn the Birmingham parade ordinance, and to prevent future uses of injunctions against civil rights marchers. The case is [Wyatt Tee] Walker v. City of Birmingham. It is not decided until 1967 by the Supreme Court, which upholds King's arrest and imprisonment on basically procedural grounds:

| The text of the Supreme Court decision, written by Potter Stewart | My commentary and questions |

| On Wednesday, April 10, 1963, officials of Birmingham, Alabama, filed a bill of complaint in a state circuit court asking for injunctive relief against 139 individuals and two organizations. | With whom does the opinion begin? How are those people described? What do we usually think of when we hear "city officials"? How else could these particular men be described? (Hint: the Klan was powerfully influential in city government). How would the narrative read if it started with King and the other civil rights leaders? |

The bill and accompanying affidavits stated that during the preceding seven days:

|

How are the petitioners described? Were the petitioners a "mob" -- or a group of citizens assembled to petition for the redress of their grievances? Is there a corect answer to this question? What is not said about them? What context is missing? What are their alleged actions? How else could the SCLC's actions be described? |

| The bill stated that these infractions of the law were expected to continue and would "lead to further imminent danger to the lives, safety, peace, tranquility and general welfare of the people of the City of Birmingham," and that the "remedy by law [was] inadequate." | Apart from unrest, what else might the city officials fear? |

| The circuit judge granted a temporary injunction as prayed in the bill, enjoining the petitioners from, among other things, participating in or encouraging mass street parades or mass processions without a permit as required by a Birmingham ordinance | Is the ordinance constitutional? If not, why not? Why did Connor get an injunction instead of arresting people under the ordinance? Does the opinion explain his motivations? Would it read differently if it did? |

| Five of the eight petitioners were served with copies of the writ early the next morning. Several hours later four of them held a press conference. There a statement was distributed, declaring their intention to disobey the injunction because it was "raw tyranny under the guise of maintaining law and order." At this press conference one of the petitioners stated: "That they had respect for the Federal Courts, or Federal Injunctions, but in the past the State Courts had favored local law enforcement, and if the police couldn't handle it, the mob would." That night a meeting took place at which one of the petitioners announced that "[i]njunction or no injunction we are going to march tomorrow." The next afternoon, Good Friday, a large crowd gathered in the vicinity of Sixteenth Street and Sixth Avenue North in Birmingham. A group of about 50 or 60 proceeded to parade along the sidewalk while a crowd of 1,000 to 1,500 onlookers stood by, "clapping, and hollering, and [w]hooping." | Does the SCLC "respect" the state courts? Should it? Why are the SCLC's disrespectful words quoted here? (See footnote #3: petitioners "contend that the circuit court improperly relied on this incident in finding them guilty of contempt, claiming that they were engaged in constitutionally protected free speech. We find no indication that the court considered the incident for any purpose other than the legitimate one of establishing that the participating petitioners' subsequent violation of the injunction by parading without a permit was willful and deliberate." Why then quote them verbatim?) The crowd is described as "hollering and [w]hooping." How else could they be described? Who's being quoted here? |

| Some of the crowd followed the marchers and spilled out into the street. At least three of the petitioners participated in this march. Meetings sponsored by some of the petitioners were held that night and the following night, where calls for volunteers to "walk" and go to jail were made. On Easter Sunday, April 14, a crowd of between 1,500 and 2,000 people congregated in the midafternoon in the vicinity of Seventh Avenue and Eleventh Street North in Birmingham. One of the petitioners was seen organizing members of the crowd in formation. A group of about 50, headed by three other petitioners, started down the sidewalk two abreast. At least one other petitioner was among the marchers. Some 300 or 400 people from among the onlookers followed in a crowd that occupied the entire width of the street and overflowed onto the sidewalks. Violence occurred. Members of the crowd threw rocks that injured a newspaperman and damaged a police motorcycle. | What of factual significance is described here? Why say "Violence occurred"? (NB: Garrow mentions no violence; Branch says MLK was "suddenly seized without warning by police.") Were the city officials justified in their initial fears? (They feared violence; violence occurred.) Does this make the injunction valid? |

| The next day the city officials who had requested the injunction applied to the state circuit court for an order to show cause why the petitioners should not be held in contempt for violating it. At the ensuing hearing the petitioners sought to attack the constitutionality of the injunction on the ground that it was vague and overbroad, and restrained free speech. They also sought to attack the Birmingham parade ordinance upon similar grounds, and upon the further ground that the ordinance had previously been administered in an arbitrary and discriminatory manner. The circuit judge refused to consider any of these contentions, pointing out that there had been neither a motion to dissolve the injunction, nor an effort to comply with it by applying for a permit from the city commission before engaging in the Good Friday and Easter Sunday parades. | Why didn't the SCLC go back to Connor for a permit? How does the Court want the SCLC to treat Connor? Does Connor merit this? |

| Consequently, the court held that the only issues before it were whether it had jurisdiction to issue the temporary injunction, and whether thereafter the petitioners had knowingly violated it. Upon these issues the court found against the petitioners, and imposed upon each of them a sentence of five days in jail and a $50 fine, in accord with an Alabama statute. | |

| ... The generality of the language contained in the Birmingham parade ordinance upon which the injunction was based would unquestionably raise substantial constitutional issues concerning some of its provisions. ... The petitioners, however, did not even attempt to apply to the Alabama courts for an authoritative construction of the ordinance. | What is the Supreme Court's attitude toward the Alabama courts? Were those courts legitimate? |

| ...The breadth and vagueness of the injunction itself would also unquestionably be subject to substantial constitutional question. But the way to raise that question was to apply to the Alabama courts to have the injunction modified or dissolved. | |

| ... The petitioners also claim that they were free to disobey the injunction because the parade ordinance on which it was based had been administered in the past in an arbitrary and discriminatory fashion. In support of this claim they sought to introduce evidence that, a few days before the injunction issued, requests for permits to picket had been made to a member of the city commission. One request had been rudely rebuffed, and this same official had later made clear that he was without power to grant the permit alone, since the issuance of such permits was the responsibility of the entire city commission. | Petitioners raise the issue of past discrimination. What kind of discrimination would this have been? (racial) Has race been mentioned at all in the opinion? Why does Justice Stewart say "a member of the city commission" instead of "Connor"? (According to testimony by Lola Hendricks, this is what happened: "I asked Commissioner Connor for the permit, and asked if he could issue the permit, or other persons who would refer me to, persons who would issue a permit. He said, 'No, you will not get a permit in Birmingham, Alabama to picket. I will picket you over to the City Jail,' and he repeated that twice." Why does Steward say that Connor "made clear" his lack of authority to issue permits? (Connor actually did issue permits to other groups.) Why not use the words "asserted" or "claimed"? |

| This case would arise in quite a different constitutional posture if the petitioners, before disobeying the injunction, had challenged it in the Alabama courts, and had been met with delay or frustration of their constitutional claims. But there is no showing that such would have been the fate of a timely motion to modify or dissolve the injunction. There was an interim of two days between the issuance of the injunction and the Good Friday march. The petitioners give absolutely no explanation of why they did not make some application to the state court during that period. | What was the significance to the Civil Rights Leaders of Easter? Why was it important for them to have innocent people jailed on Good Friday and released on Easter Sunday? How does this reasoning and motivation collide with that of the legal system ? |

| ... The rule of law that Alabama followed in this case reflects a belief that in the fair administration of justice no man can be judge in his own case, however exalted his station, however righteous his motives, and irrespective of his race, color, politics, or religion. This Court cannot hold that the petitioners were constitutionally free to ignore all the procedures of the law and carry their battle to the streets. One may sympathize with the petitioners' impatient commitment to their cause. But respect for judicial process is a small price to pay for the civilizing hand of law, which alone can give abiding meaning to constitutional freedom. | The "civilizing hand of law." Does this value count against the marchers? Or against Connor? "... which alone can give abiding meaning to constitutional freedom." Alone? Contrast MLK, in Atlanta (1962): "legislation and court orders can only declare rights. They can never thoroughly deliver them. Only when people themselves begin to act are rights on paper given life blood." |