« January 2006 | Main | March 2006 »

February 28, 2006

Shakespeare in retirement

I recently finished Stephen Greenblatt's Will in the World, a chronological series of essays about Shakespeare's life and its influence on his work. It leaves me thinking about the reasons for Shakespeare's early retirement around 1611. That year he turned 47 and was probably not in bad health, for he had bought an expensive annuity that would only pay off if he faced decades of retirement (Greenblatt, p. 364). Why then did he quit London and write nothing more on his own? Greenblatt explores three explanations, and I will add a fourth of my own that's completely speculative:

1. It was a very sensible business decision to retire. Shakespeare had worked extremely hard and become wealthy. But the risks were high. Any time there was a sign of the plague, the authorities would close down all theaters. A fire like the one that destroyed the Globe in 1613 could destroy Shakespeare's investments in his company. In 1604, he and his colleagues had inadvertently offended the King with the Tragedy of Gowrie, a dramatization of James' own past. Such mistakes were easy to make and could cause the government to close companies or even to impose grim punishments like shaving off actors' noses or chopping off their hands. Shakespeare may have decided to quit while he was ahead.

Why didn't he continue to write plays in Stratford, giving up his roles as actor, producer, and theatrical investor? Perhaps it's an anachronism to imagine Shakespeare as a simple writer: he had always been a creator of theatrical entertainments, involved in all aspects of the work from writing to costumes. Shakespeare showed little interest in the publication of his own plays, so it may not have occurred to him to write without also acting and producing. (He collaborated with John Fletcher on three plays after 1611, and his motive may have been to help Fletcher or the company.)

2. Greenblatt speculates that Shakespeare wanted to spend time with his daughter Susanna. His will was carefully written to benefit her above all others. The bond between fathers and daughters is a major theme in Lear, Pericles, The Winter's Tale, and The Tempest, among other plays. Shakespeare explores that relationship far more fully than he does the bond between husbands and wives. It is not such a strange thought that he would trade the stress of theatrical management in London for domestic life with a beloved child.

3. More interestingly: perhaps Shakespeare had moral or even "existential" doubts about his own power to create imaginary worlds and to move large audiences to his will. His last sole-authored play is The Tempest, in which Prospero manipulates all the other characters by contriving an elaborate plot and even magically creating specters who act out scenes.

... graves at my command

Have waked their sleepers, oped, and let 'em forth

By my so potent art. But this rough magic

I here abjure.

Greenblatt compares Shakespeare's power to "ope" the graves of Lear, Caesar, Hamlet, Henry IV and all the other historical figures of his plays, who come magically to life. Could Shakespeare, like Prospero, have "abjured" that power for ethical reasons? We could supply reasons specific to Shakespeare's age. Before and during the Reformation, many were skeptical of fiction (because it lied), of tragedy (because it suggested that creation was not fundamentally good), and of entertainment (because it distracted from faith). Shakespeare could have shared those worries. Or perhaps this man who surpassed all others in the capacity to create illusions with words saw dangers that transcended his time.

4. We know that Shakespeare discovered how to represent the interior life of characters on the stage. He invented the soliloquy and also learned (as I think the ancients had) to use irony to give glimpses of characters' inner thinking. Not only could he hint at the private thoughts of characters, but he could conjure up their social and historical contexts with just a few words of description. However, the stage is not really the best vehicle for exploring psychology or for depicting social context. The novel offers far richer possibilities for those purposes. Shakespeare read Don Quixote, which provided the plot for his lost collaborative play, Cardenio (ca. 1613). I like to think of him retiring to Stratford, to an annuity and to quiet surroundings, so that he could write a different kind of work--perhaps the first great English novel, or conceivably some other narrative text, such as a biography or even an autobiography. Perhaps that work died unfinished with its author.

Many critics have noted that Shakespeare had an extraordinary capacity not to take an authorial position on the issues of his plays, but rather to depict a range of perspectives. Coleridge called this skill "myriad-mindedness"; Keats named it "negative capability"; and Arnold said that Shakespeare was "free from our questions." A novelist, too, can attain neutrality or multi-mindedness: Cervantes is an excellent example. But negative capability in a narrative requires different techniques from those appropriate in drama. If Shakespeare tried to write a novel, would he have struggled to suppress his own opinions? Or would he have seized the opportunity, finally, to say what he believed?

Posted by peterlevine at 7:30 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 27, 2006

a market failure in higher ed (the Summers case)

In the highly competitive global market for college students and faculty, Harvard is the leader. A major consulting firm that was hired to advise Oxford (I think it was McKinsey & Co.) found that Oxford could potentially compete with any institution in the world except Harvard. In a business obsessed with rankings, Harvard sits on top, and everyone else emulates it.

President Larry Summers was popular with students (Harvard's "customers"), but unpopular with faculty (the employees). He was forced out by the Trustees, who have a fiduciary duty to protect the institution. Although we know that students never have much clout, it's a bit of a puzzle that the faculty should prevail in an organization that is so successful at attracting student-applicants.

Of course, it's possible that Summers was forced to resign because he was wrong on the merits, and the Trustees saw that. I suspect, however, that the issue was not his comments about women scientists or his confrontation with Cornel West (on which the Trustees might have thought he was wrong). The issue was a set of curricular and budgetary reforms that promised to enhance Harvard's actual education while eroding the power of tenured professors in the Arts and Sciences. On those matters, Summers was very likely correct.

I want to emphasize that I don't see students as customers. Nevertheless, an economic analysis is useful for revealing how institutions actually work (as opposed to how they should work). Here are two contrasting views of the economics of the situation:

1. Gary Becker, in the Becker-Posner blog:

The American college and university system is widely accepted as the strongest in the world. This is why American universities are filled with students from abroad, including those from rich nations with a long history of higher education, like Germany and France.I conclude from this that the American university system must be doing many things right, at least relative to the other systems. And what is right about this system is rather obvious: several thousand public and private colleges and universities compete hard for faculty, students, and funds. That the American system of higher education is the most competitive anywhere is the crucial ingredient in its success. ...

Given the effectiveness of the American higher education system, its governance, including the role of faculty, is probably on the whole along the right lines.

Becker thinks that Harvard made a mistake by removing Summers and that its internal structure might be improved by strengthening the president; but the overall incentives are appropriate, and the best institutions will prevail.

2. John Tierney in the New York Times (Feb. 25):

In most industries, a company would cater to customers paying $41,000 per year, but Harvard has been able to take its undergraduates for granted. ... Harvard has long known that the best students will keep coming, not for its classes but simply for its reputation. Smart students want to go where other smart students go.Suppose people picked hotels based on how intelligent they expected the other guests to be. Once a hotel got a reputation as a brain magnet, smart people would automatically go there, and hotel employees could afford to get complacent. ...

Senior professors can shunt off the more tedious jobs, like teaching freshmen or grading papers, to low-caste graduate students or visiting lecturers.

Tierney is pointing to a market failure. I think he's onto something. Each Harvard matriculant gets intellectual stimulation from smart peers, plus the reputational advantage of having attended the most competitive institution (regardless of the quality of the education offered there). Harvard is, as Tierney says, a "brain magnet."

In a sense, that's an arbitrary distinction; one year, the most successful high school students could all decide to apply to the University of Maryland, and they'd be fine if they all ended up here. But some signal must direct them to Harvard. The main signal is the reputation of the faculty. The senior professors don't have to teach; they just have to lend their names to the institution. In fact, they could probably resign and, for a time, Harvard would continue to sit on top of the rankings, simply because of its competitive applicant pool. However, Harvard must worry about the reputation of its faculty, because that is what creates the competition for students. Thus the faculty have a strategic position; thus they prevailed with the Trustees.

[PS: In passing, Becker makes a classic economist's observation: "What survives in a competitive environment is not perfect evidence, but it is much better evidence on what is effective than attempts to evaluate the internal structure of organizations. This is true whether the competition applies to steel, education, or even the market for ideas." That kind of reasoning leads people to try to increase competition in K-12 education--through vouchers--rather than analyze how schools themselves should function. Note, however, that someone must "evaluate the internal structure of institutions." Otherwise, there will be no rational plans for improvement. Competition changes incentives, for better or worse. It does not itself solve problems.]

Posted by peterlevine at 7:50 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 24, 2006

young people and rebuilding after Katrina

According to the latest AP-Ipsos poll, "About half the under-30 poll respondents -- 52 percent -- said they were confident federal money for the Gulf Coast recovery was being spent wisely. The number was much lower for respondents of all age groups -- only 33 percent."

We have three possible explanations for this gap, which are all quoted in an article by Ryan Pearson for AP's youth-oriented wire service, ASAP news. First, the youngest generation has consistently been less critical of government than older generations. More of them agree than disagree that the federal government usually acts in the genuine interests of the public. (However, a plurality won't answer the question at all because they are undecided). Second, younger people are often less well informed about current events, so perhaps they know less about the mismanagement after Katrina that has been heavily reported in the press. Third, they may be in the middle of a learning process. In the ASAP story, Abby Kiesa mentions CIRCLE's focus groups on Katrina. Abby heard mostly questions rather than firm opinions. Youth wanted to know what was happening after Katrina, why we weren't better prepared, and who was a credible source. As Public Agenda and its co-founder Dan Yankelovich argue, we often make a mistake when we confuse settled opinions with developing views--although they can look alike in a standard survey.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:11 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 23, 2006

the Bahamas

Over the President's Day weekend, my family and I visited the Bahamas. I have hesitated to blog about our trip, because I don't want to presume any knowledge or insight about a country that I saw so briefly. I find life in America mysterious and complicated enough; to say something about a foreign nation on the basis (mainly) of a two-hour tour provided by a friendly taxi driver is presumptuous.

But I enjoy recording what I happen to notice. In Miami, on the way home, I saw scores of homeless men under a kind of portico in a blighted downtown district. Back in our own neighborhood in Washington, someone asked me for money for food. I didn't see anyone that badly off in Nassau. There were some very small houses--maybe 10 feet by 10 feet. But they were mixed in with larger homes and shops. People of all ages seemed comfortable out on the streets. There may be crime, but there was no sign of fear. Our taxi driver emphasized that health care is free except for a $10 co-pay if you stay overnight at the hospital.

I don't want to romanticize life in a place that, to repeat, I know so little. But it turns out that the adult literacy rate in the Bahamas is 95.5%, life expectancy at birth is 67.2, 97% of the population has access to water and up to 94% can afford essential drugs. There are 106 physicians per 100,000 population. Women hold 20% of seats in parliament and are slightly more literate than men, although their earned income is only 64% of men's. By way of comparison, life expectancy in the US is 78 years, 100% of our population is considered to have access to safe water, and there are about 549 physicians per 100,000 people (but a lot of people can't afford to see them). I can't find adult literacy statistics for the US or the percentage of Americans who can afford drugs defined as essential--I doubt that either rate is higher than in the Bahamas. Women hold 15.1% of the seats in Congress and earn 62% as much income as men.

It occurs to me that if the 192 countries of the world were people, the US would be one of the richest, but would have some "issues." The Bahamas would be upper-middle class and would have its act together pretty well.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:56 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 22, 2006

youth civic engagement: an institutional turn

In 2005, my colleague Jim Youniss (Catholic University) and I organized a conference, funded by The Carnegie Corporation of New York, that explored a particular perspective on youth civic engagement. We tried to shift the focus away from direct efforts to change young people's civic skills, knowledge, and behavior (for example, through civic education or voter mobilization). Instead, we wanted to talk about reforms of institutions that might make participation more rewarding and welcome. The problem is not always inside young people's heads; sometimes they are right to avoid participation in the processes and institutions that exist for them. For similar reasons, it is important to study (and perhaps to change) their ordinary, daily experiences, which form the context for their civic and political engagement.

We convened more than a dozen experts: pyschologists, political scientists, sociologists, and scholars of communications and education. They ultimately produced 14 short essays that CIRCLE released yesterday as a package (pdf, 53 pages long).

I believe that these essays are quite rich and stimulating. At the risk of leaving out some of the best parts, I'll mention a few samples:

Diana Mutz argues that deliberation and participation trade-off. She finds "that although diverse political networks foster a better understanding of multiple perspectives on issues and encourage political tolerance, they discourage political participation, particularly among those who are averse to conflict. Those with diverse networks refrain from participation in part because of the social awkwardness that comes from publicly taking a stand that friends or associates may oppose. ... The best social environment for cultivating political activism is one in which people are surrounded by those who agree with them, people who will reinforce the sense that their own political views are the only right and proper way to proceed. Like-minded people can spur one another on to collective action, and promote the kind of passion and enthusiasm that is central to motivating political participation." Jane Junn challenges the idea that education is simply good for civic participation. "While formal education may encourage the development of cognitive ability and individual resources, it may also be the case that these skills are less relevant to one's placement in the hierarchy of American life. Instead, the importance of education to stratification may be the role it plays as a powerful socialization device, teaching students who are successful and who progress through educational institutions to also become initiated into the hierarchical norms of commerce, politics, and social life. In short, education may be a particularly effective means of reproducing cultural, political, and economic practices. ... Education may reproduce and legitimate structural inequalities that in turn drive vast disparities in wealth, and nurture the persistence of the dominance of the in-group to the systematic disadvantage of out-groups. ... In its role as a powerful socializer, education teaches the ideology of meritocracy, by grading on normal curves and assuring those who finish on the right tail that they will succeed because they deserve to. ... It is necessary to have some mechanism which reliably reproduces the ideology that maintains the positions of power for those at the top who benefit from the system as it already exists. When outcomes are positional or scarce--when not everyone can be rich, and not everyone can be granted admission into a top school--the liberal democratic ideology must have an answer to its production of unequal outcomes. Merit can be used as a justification for inequality of outcomes in a system where the rules are supposed to be fair." Dietlind Stolle characterizes the new forms of politics that we see in the anti-globalization movement and elsewhere. (1) "These new forms of participation abandon traditional (that is to say formal and bureaucratic) organizational structures in favour of horizontal and more flexible ones. Loose connections, in other words, are rapidly replacing static bureaucracies." (2) "In general these new initiatives are also less concerned with institutional affairs, such as party politics, which brings them into sharp contrast with more traditional political organisations. Life-style elements are being politicized and although the actors no longer label their action as being expressly 'political,' these preoccupations do lead to political mobilization." (3) "These new forms of participation ... rely on apparently spontaneous and irregular mobilization. The signing of petitions, or participation in protests and consumer boycotts all seem based on spontaneity, irregularity, easy exit and the possibility of shifting-in and shifting-out." (4) "New forms of participation are potentially less collective and group-oriented in character. ... While this form of protest and participation can be seen as an example of co-ordinated collective action, most participants simply perform this act alone, at home before a computer screen, or in a supermarket."

Posted by peterlevine at 9:35 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 21, 2006

the moral world of children

Phillip Larkin, the great English poet, once said, "Until I grew up I thought I hated everybody, but when I grew up I realized it was just children I didn't like. Once you started meeting grown-ups life was much pleasanter. Children are very horrible, aren't they. Selfish, noisy, cruel, vulgar little brutes."

In reading anything by Larkin, you have to make allowances for a combative, hostile stance toward women, immigrants, animals, and children. This is a stance, and its main point is to communicate the narrator's own flaws and vulnerability. He wasn't a nice man, but he was a profound ironist. He didn't exactly mean what he wrote.

Nevertheless, I think Larkin had a point in the passage quoted above--not about all kids, but about children who are raised the way his generation was in middle-class, provincial England ca. 1930. If you leave children alone to create their own social world and to interact freely with one another, they can indeed be selfish and cruel. In the society of Larkin's youth, discipline was strict (sometimes even brutal), but adults didn't interfere much in children's social world. They punished kids for playing dangerously or for annoying or inconveniencing grown-ups, not for being mean to one another. In fact, adults' strictness tended to drive children into a separate world in which the stronger kids dominated. Left completely to their own devices, children will make Lord of the Flies.

But of course you can interfere to make children kind and fair to one another. Or you can integrate kids into families and adult communities so that they don't have a fully autonomous social world. There is a lot of variation in the degree to which children and adolescents are allowed to form autonomous youth cultures. I think less autonomy is generally better.

(This position has implications for the way we organize schools. In particular, it means that we should try to make schools smaller and connect them to adult institutions instead of isolating them behind big lawns or barred windows.)

Posted by peterlevine at 7:18 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

February 17, 2006

Koufax Awards

Since my family and I are traveling, I don't expect to post anything until Tuesday. Meanwhile, I'm flattered that this blog has been nominated for the Koufax Award in the "best expert blog" category. Voting hasn't started yet, but please consider voting for me when the polls open. Some of the other nominees attract easily 100 times as much daily traffic as I do, so I'm going to be buried. But I'd love to get at least a few votes.

Posted by peterlevine at 4:14 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 16, 2006

Cheney and the press

Jay Rosen has the best commentary on how Dick Cheney has handled the press after the shooting accident. As a foil, Jay quotes former White House Press Secretary Marlin Fitzwater: "If [Cheney’s] press secretary had any sense about it at all, she would have gotten the story together and put it out. Calling AP, UPI, and all of the press services. That would have gotten the story out and it would have been the right thing to do, recognizing his responsibility to the people as a nationally elected official, to tell the country what happened."

Jay replies: "But Cheney figures he told the country 'what happened.' What he did not do is tell the national press, which he does not trust to inform the country anyway. ... He treated the shooting as a private matter between private persons on private land that should be disclosed at the property owner's discretion to the townsfolk (who understand hunting accidents, and who know the Armstrongs) via their local newspaper, the Corpus Christi Caller-Times."

Note the synecdoche in Fitzwater's statement: API and UPI stand for the people and the country. Cheney doesn't accept that, and neither do I--not in the age of blogs and other peer-to-peer media. A few national news organs do not have a right to be informed about anything in particular--especially since the news will get out anyway. However, Jay also argues that the old relationship between the national press corps and the White House served as a check on the latter, and that something must be able to challenge the presidency.

For my part, I have two incompatible reactions to this affair:

1. I wish Americans paid less attention to the private behavior of public officials. Private acts are easier to understand than policy, but they give poor insight into public leadership. (For instance, the accidental shooting makes a nice metaphor for Cheney's handling of the Iraq war, but anyone could have done the same thing. The connection is symbolic and basically meaningless.) Furthermore, the emphasis on private behavior distracts attention from more serious matters; it adds an unecessary element of randomness to national affairs; and it puts officials in a fishbowl, thereby persuading some good people not to enter public life in the first place.

Therefore, I wish that Bill Clinton had gotten in trouble (with his wife and perhaps with the law) for having extramarital sex with an intern in his own office. But I wish that the press and the public hadn't cared. I wish that the Lewinsky story had appeared on page A23 and attracted no notice. Likewise, in a country of active, thoughtful, and responsible citizens, no one would care about Cheney's shooting accident. They'd be too busy thinking about earmarks, FISA, and Iraq.

2. On the other hand, it is obvious that people use the private behavior of politicians as heuristics to assess their public behavior. It's easier to understand hunting accidents and sexual harrassment than energy policy and deficits. According to Robert Wuthnow, people not only judge politicians and administrations on the basis of their private behavior; they actually draw conclusions about human nature based on what they observe politicians doing.

If this is true (and impossible to change), then public officials are publicly accountable for their private behavior, just because it can affect the administration, the party, the institution, and even the nation that they serve. Then I think the following logic holds: Dick Cheney can affect public trust by how he acts in private. A proportion of the public strongly distrusts him. Therefore, he'd better try to increase their trust by going straight to the national press corps as soon as he has a problem and tearfully confessing his deepest thoughts on evening TV. It isn't dignified, but it's the way things work in a celebrity culture with low levels of serious civic engagement.

Posted by peterlevine at 1:32 PM | Comments (4) | TrackBack

February 15, 2006

are sports good for democracy?

Joey Cheek (age 26), the winning speedskater, has decided to donate his whole Olympic prize to Right to Play, a nonprofit that serves poor kids in the developing world. He also took the opportunity to speak out on an issue. "In the Darfur region of Sudan, there have been tens of thousands of people killed," Cheek said. "My government has labeled it a genocide. I will be donating it specifically to a program to help refugees in Chad, where there are over 60,000 children who have been displaced from their homes."

This is just an anecdote about one American athlete who pays attention to social issues and takes action. His story helps to balance all the anecdotes about bad behavior by athletes. But what happens if we move from anecdotes to data? Today, CIRCLE releases two studies on the relationship between athletics and civic engagement. We find that sports participants are much more likely than other youth to volunteer, vote, and follow the news. That correlation does not prove that sports causes civic participation. However, the correlation remains after we control for all the other variables measured in the survey, including academic success and participation in other groups.

Today's release is getting quite a bit of interest. I did interviews this morning for national CBS radio news and local drivetime radio in Washington (WTOP). Also, that's my hand on the bottom of the basketball.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:52 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 14, 2006

interracial tolerance among the young

My organization is cited in this story in USA Today: Sharon Jayson, "New generation doesn't blink at interracial relationships":

Ryan Knapick and Josh Baker have been best friends since fifth grade. Colette Gregory entered the picture in high school. She and Josh are dating now. Knapick is white, Gregory is black and Baker is half-Hispanic. To them, race doesn't matter. ...He and his friends are among an estimated 46.3 million Americans ages 14 to 24 — the older segment of the most diverse generation in American society. (Most demographers say this "Millennial" generation began in the early 1980s, after Generation X.) These young people have friends of different races and also may date someone of another race.

This age group is more tolerant and open-minded than previous generations, according to an analysis of studies released last year by the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement, part of the University of Maryland's School of Public Policy. The center focuses on ages 15 to 25.

While the youngest generation is the most tolerant on record--and that's a fact worth celebrating--our research showed a gap between attitudes and behaviors. For example, only 4% of young Americans (age 18-25) say that they favor segregated neighborhoods. That's down from about 25% in the 1970s and it's lower than the rate among people over age 25. This change is almost entirely attributable to the arrival of new generations: individuals do not seem to change much over their lifetimes. (Source: General Social Survey.)

Nevertheless, more than half of young churchgoers say that their congregations have members of only one race--the same rate as among older people, and not much different since 1975 (GSS). In the Social Capital Benchmark Survey (2002), 66% of young White people who belonged to participatory groups said that all the other members were also White. This rate was not much different for older Whites. In the same survey, just 20% of young people claimed that they had invited a friend of another race to their house--better than the 6% rate among adults over age 56, but still not so common.

Will tolerant answers to survey questions translate into real social change if people remain quite segregated in their daily lives?

Posted by peterlevine at 8:11 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

February 13, 2006

religion and politics in the Moslem world and the USA

A colleague returned several months ago from a distinguished meeting of intellectuals from Europe, America, and the Middle East. He reported that the Islamic participants had confused us with France. That is, they thought that the United States was a highly secular, formerly Christian country with low tolerance for faith. Presumably, they drew generalizations about the "West" on the basis of what they know about the European countries that had once colonized them and that now absorb many of their emigrants.

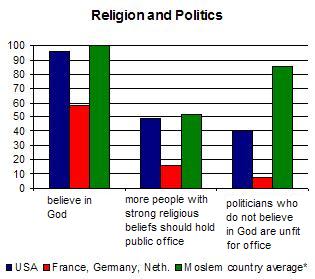

In reality, Americans' opinions about religion and politics sometimes lie closer to those in the Islamic world than to those of Western Europeans. Above, I show data from the World Values Survey (1999-2003). The "Moslem country average" is an unweighted mean of Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, Pakistan, and (for the belief in God question only) Saudi Arabia. I show an average of France, Germany, and the Netherlands as representative of Western Europe.

Since Denmark is in the news, I'll mention these results: 68.9% of Danes believe in God (compare 100% in Pakistan and Egypt, and 96% in the US), 3.7% of Danes think that a politician who doesn't believe in God is unfit for office (compare 94.9% in Pakistan); and 5.6% of Danes think that it would be good for more religious people to hold public office (compare 91.2% of Egyptians).

Posted by peterlevine at 7:16 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 10, 2006

can the Internet democratize institutions?

Yesterday, I heard a talk about whether the Internet can help to democratize institutions such as the World Bank and WTO. Proposals for that purpose include posting internal deliberations online, allowing people to file comments by email, or even allowing anyone to edit draft documents on websites ("wikis"). The main response is that the Internet is just a tool; it doesn't change the basic structure of governance. For instance, there are already lots of interesting and wide-ranging discussions within offices and departments of the World Bank. Outsiders could be enabled to participate in those discussions through online tools. But if real decisions are still made rather opaquely by a few individuals, then the online discussion will just mislead outsiders into believing that they have influence. The Internet itself does not change the incentives to share power.

I agree that the Internet cannot itself change the governance of institutions. However, to a degree, the Internet is changing the institutions that count. Two important examples:

Standards have powerful impact on our lives. They are what allow all our computers to interconnect. They can be constructed in such a way as to favor, disfavor, block, conceal, reveal, or otherwise influence all of our online transactions. But standards are not written by the institutions that were considered by political theorists 50 years ago: not by legislatures, courts, diplomats, or regulatory agencies. Sometimes, a person (e.g., Tim Berners-Lee) just writes standards and they proliferate. Perhaps they can be changed by means of political pressure, but not in traditional ways. For instance, no law or government could simply change the standards for email or the Web, which are thoroughly dispersed Ten years ago, what a daily newspaper should do was an important question. Today, it is a less important issue, because newspapers have lost overall market share and clout to various kinds of websites, including blogs. Their market share could drop to zero.

[PS: My current grad student Tony Fleming has created a great specialized blog on the competition to be the next UN Secretary General. Tony provides detailed information and news as well as an opportunity to propose questions for the leading candidates. That's a nice use of blog technology to press a major international body to be more transparent.]

Posted by peterlevine at 3:05 PM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

February 9, 2006

Robert George on civic education

Thanks to Brett Marston for directing me to Robert P. George's essay, "What Colleges Forget to Teach." This a thoughtful comment by a major conservative scholar. In essence, George objects to the balance of political ideas and materials that college students experience as undergraduates and before they arrive on campus. They should, he thinks, understand the importance of limiting the powers of the federal government, of restraining judges, and of empowering the states. They should understand the lasting virtues as well as the vices of the American constitutional order.

I agree with all this and find it useful--especially George's conclusion that "the reform and renewal of civic education in our nation is a noble cause. We must make it an urgent priority." My agreements with George are more important than my disagreements. However ...

1. I'm not convinced that the balance of ideas that students experience is so far from what George would prefer. Generally, when either liberals or conservatives decry the content of social studies classes, they do so innocent of any statistical evidence about what is actually taught and discussed in schools. There are anecdotes about egregious teaching that can incense people across the spectrum from Howard Zinn to Robert George himself, but no one knows how common these stories are. In 2004, we asked a national sample of young Americans to recall two major themes from their social studies classes:

29.8% recalled "great American heroes and virtues of the political system" 38.6% recalled "The Constitution or U.S. system of government and how it works" 7.8% recalled "racism and other forms of injustice" 14.8% recalled "wars and military battles" 5.2% recalled "problems facing the country today"

These results should make George happy (and lefties unhappy), although I admit that George might not like some of the details of what students learn. For instance, it's possible that they are exposed to a liberal interpretation of the Constitution rather than the views of the Federalist Society--but who knows?

Second, what students are taught is only part of the issue. There's also the question of how they are taught. Do they sit in large lecture halls being informed about the Constitution (from a radical, liberal, or conservative perspective)? Do they debate constitutional principles in small groups, moderated by a well-informed teacher? Do they conduct ambitious projects of research, service, or advocacy that involve constitutional principles? I'm not wedded to any one approach, but I suspect that the way we teach has much more impact than what values we try to convey in lectures.

3. George is no doubt sincerely committed to civility and to an open-ended, ideologically diverse discussion of principles. He is perhaps right that his own perspective is undervalued in the academy. But the difficult part is not agreeing on civility or diversity as abstract principles--the hard part is making concrete judgments. For instance, George describes the situation in academia as "dire" and provides some illustrative "horror stories," such as Princeton's decision to give a "distinguished chair in bioethics to a fellow who insists that eating animals is morally wrong, but that killing newborn human infants can be a perfectly moral choice." That fellow is, of course, Peter Singer. His view is a coherent application of utilitarianism, which is a 200-year-old position with roots in ancient thought and much influence on modern conservatism. I'm no utilitarian, but I don't see how a university can regret attracting one of the most original and influential philosophers of the current era.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:23 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

February 8, 2006

what do parents want?

We human beings are not born free. We are born as completely dependent, totally naive little creatures that are easily influenced and controlled by adults, especially parents. If you want a society dedicated to freedom, then you have to ask whether parents are raising their kids to value liberty. If not, then you face a conundrum: you may have to force people to raise free children. Indeed, this is a common rationale for public schools, which are supposed to expose kids to a broad array of values from which they can choose. If you favor a basket of values that includes compassion, patriotism, and tolerance as well as freedom, then you must certainly worry about whether parents teach these values.

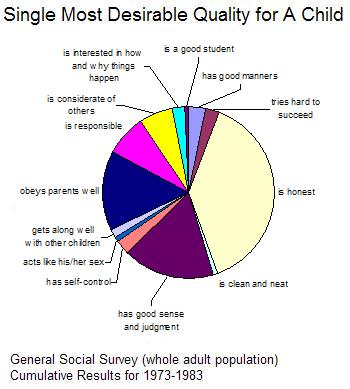

I am therefore highly curious about what parents want for their kids. The pie chart below shows the "qualities" that parents (defined as individuals who had ever had kids) said that they valued most in children. They were surveyed between 1973-1983. I haven't found more recent data, although it may exist.

Some observations: Honesty dominates, far outstripping considerateness and getting along with others. Only three percent chose the intellectual virtues of curiosity and studiousness. (I wonder whether that number has increased since 1983, as we move deeper into the high-tech era.) Obedience to parents is not the top choice of many people. However, more than half of respondents chose obedience as one of their top three virtues.

[NB: I aggregated a decade's worth of data to make the sample size as large as possible, but there are no important changes in the answers over that period.]

Posted by peterlevine at 10:04 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 7, 2006

into the fray

Somewhat contrary to my usual practice, I hereby opine (without expertise or evidence) on two hot topics:

1. New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin has attracted much criticism--and has apologized--for saying, "This city will be a majority African-American city. It's the way God wants it to be. You can't have it no other way. It wouldn't be New Orleans." Nagin has been called racist for setting a racial target in that way. It would certainly be out of bounds for someone to suggest (for instance) that Denver must stay 80.6% white. However, lots of people want to preserve or recreate the traditional culture of New Orleans. That culture is inextricably linked to race. I realize that the city was never monoracial. In fact, the traditional culture of New Orleans will be lost if working-class white Cajuns or rich whites from the Garden District choose not to return. It's a subtle question whether the city needs an African American majority to restore its culture. But New Orleans was 67% Black before Katrina, so anything below 50% would be a big drop--and a big cultural change.

"Culture" is a more comfortable concept than race, but the two cannot be separated. If you hope to preserve or restore the characteristic culture of New Orleans, you have to bring back the Black population.

2. Danish cartoons satirizing (or did they simply depict?) Mohammed have ignited riots in at least half a dozen countries. In cases like this, it seems important to separate the questions that could be asked:

Should the Danish Government ban the publication of these cartoons or punish the responsible newspaper, the Jyllands-Posten? No: that would violate freedom of the press. Should the Jyllands-Posten have published the cartoons? No: they aren't funny, they don't have news value, and their only purpose appears to have been to demonstrate that the press is free in Denmark. That's a bad editorial decision, to put it mildly. Should newspapers in several other European countries republish the cartoons to establish their own freedom? No: duplicating a bad editorial decision is an even worse one. In response, should people attack the Danish, Norwegian, Austrian, and US embassies or consulates in multiple countries? No: that's violent. It's also a basically impotent form of rage that mainly demonstrates the vulnerability of the rioters.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:51 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 6, 2006

citizenship: choice and duty

Russell Arben Fox has written a thoughtful essay on localism, populism, and participation. He is skeptical that we can increase the quality or quantity of civic engagement by tinkering with the political system--for instance, by changing the way we draw electoral districts or by decentralizing power. The root of the problem, Fox thinks, is psychological; it is the "privatized model of the modern democratic citizen."

Today, people don't feel assigned to duties in communities. Instead, they are supposed to make judicious choices among politicians and policies in order to get desired outcomes. But it is often easier to move one's jurisdiction than to affect its policies. ("Exit" is easier than "voice.") People congregate in the most privileged geographical communities that they can afford, rather than trying to improve the more diverse communities from which they came.

In short, the overwhelming success--depending on how you define the term--of modern market economies has had the result of many citizens adapting themselves to habits of gratification, self-actualization, immediacy, individuation, and internalized (that is, nonpublic) rationalization. Decisionmaking has been reduced in the lives of too many of us to a perpetually self-generated and always self-revisable internal calculus: what do I want, and what do I want now? I am not saying the disciplines and expectations associated with free markets are flawed; I am saying, however, that market-appropriate behaviors are not appropriate to self-government. A relatively successful market economy, combined with a superficial sense of equality bequeathed to us through a naive understanding of one's 'rights,' results in a general indifference towards others so long as one's own rights and property are acknowledged; hence, the more the dominant segments of society are socially and economically homogenized (enjoying at least superficially an easily replicable level of prosperity across society), the easier it is for those citizens in that class to retreat within themselves and assume everyone else will do likewise. Our sensitivity to truly public matters decline, and our political muscles atrophy. Of course, the enormous leaps in personalized technology, which have allowed us to connect ourselves to networks of art and information that involve no collective determination or distribution, as well as the abandonment of truly involving civic requirements (like a draft), only reifies this process further.

I largely agree and would add some supporting points. First, there is evidence that citizenship has shifted from a model of ascribed duties to one of choice. That process of "modernization" occurred in the Progressive Era and was marked by such reforms as: the secret ballot, attacks on political parties (which represented identity groups), the rise of a nonpartisan, independent press, and a profound shift in education. (Instead of sermonizing about duties, schools and universities began to provide arrays of autonomous academic methods and disciplines from which students could freely choose.)

Second, I agree that the new model of citizenship has flaws:

Making judicious choices among policies is very demanding. It takes time, information, and motivation. If this is what citizenship requires, many people will not participate at all. For instance, when party-line voting declines, so does turnout. As Gerry Stoker writes in a passage that Fox quotes, a market system creates expectations of choice, ease of transactions, efficiency, and customer-service that cannot be met in politics, because politics involves debate and conflicting interests. Therefore, people accustomed to consumerism will tend to shun politics. At some deep level, a life spent making instrumental choices is unsatisfying. Perhaps we can choose political parties and politicians in order to advance non-political goals, such as security. But if we choose our family ties, our neighborhoods, our religions, and everything else for instrumental reasons, what is the purpose of it all?

Third, I agree with Fox that the modernist definition of citizenship is here to stay; we cannot return to a widespread sense of ascribed duty. In 2002, we surveyed young Americans and asked how they felt about voting. Thirty-one percent said it was a right, and 34% said it was a choice. Twenty percent said that it was a responsibility, and 9% said that it was a duty. These results may change a little over time, but they will not turn upside-down.

Nevertheless, I suspect that there are political reforms that could improve the current situation. Civic engagement does have an intrinsic appeal, at least for some people some of the time. There are few other venues in which one can deal with diverse peers on terms of rough equality, addressing serious and dignified concerns. Thus, for some people, opportunities to participate create lasting habits; engagement is self-reinforcing. This is especially true for youth: a mass of research in developmental pyschology shows that civic experiences in adolescence have lifelong effects.

This is where localism comes back. Fox is right that "professional turf-guarding can occur in local jurisdictions." However, the dramatic consolidation of such jurisdictions has left a lot fewer professionals guarding a lot more turf. Elinor Ostrom calculates that in 1932, 900,000 American families had one member with formal responsibilities on a government panel or board, such as one of the 128,548 school boards then in existence. Given rotation in office, well over 1 million families had some policymaking experience in their own recent memories. Today, thanks to consolidation, there are only 15,000 school districts, an 89% decline. Meanwhile, the population has more than doubled. The result is a decline of probably 95% in all opportunities to serve in local government. The same thing has happened in high schools: a three-generation panel study run by Kent Jennings and Laura Stoker finds a 50% decline in participation in most student groups, thanks largely to the consolidation of schools. (Fewer schools mean fewer seats on student governments.)

In short, I agree that modernization has created a problematic definition of citizenship (although the older sense of duty had its drawbacks, too). But I think that we could get considerably better results if we increased opportunities to participate.

Posted by peterlevine at 1:34 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

February 3, 2006

strengths and weaknesses of volunteer networks

As I write, I'm in my third consecutive meeting of a different volunteer network or coalition. These three networks (and others that I know) share the following features: One or more grants funds a staff, which ranges in size from less than one full-time person to a substantial secretariat. Individuals belong and devote substantial amounts of volunteer time. Organizations also belong, and some donate their employees' paid time for projects.

Although each network works differently, I think I've noticed some patterns about what volunteers will and will not do. (Here I include paid employees whose time is volunteered by their organizations):

1) Volunteers will plan and run meetings and conferences, even doing hard, detailed work on invitation lists, agendas, and menus. But they will not reliably write up the results of meetings for public distribution. After a meeting, writing feels like a chore, and there's usually no specific deadline. Therefore, many meetings leave no tangible public record.

2) Volunteers will write grant proposals, because proposals are plans that determine the work that will actually be done later on. However, they will not do the other work involved required to obtain grants, such as identifying potential funders. If they have their own contacts with foundations, most won't share them.

3) Volunteers will handle pleasant human interactions, but will avoid difficult relationships.

4) Volunteers may provide regular, written information under their own names and control, but few will contribute in a sustained way to collective writing projects. That problem can be overcome with scale but is serious in small networks.

5) Volunteers will generate wonderful ideas but are much less likely to implement them.

Posted by peterlevine at 1:45 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 2, 2006

Orhan Pamuk, My Name is Red

I've been wanting to write something insightful about this novel, which I read recently. To state that is is a masterpiece is not nearly as convincing or useful as to interpret it or elucidate one of its many themes. Unfortunately, I haven't had a chance to collect my thoughts about My Name is Red. Rather than leave it unmentioned, I'd at least like to express my admiration for this remarkable book. It contains intricate, completely original puzzles and stories on metaphysical subjects--worthy of Borges. However, Borges was uninterested in human beings and couldn't sustain a plot or create appealing characters. My Name is Red revolves around two people who are richly imagined and likeable. They interact with numerous other people, at least two of whom have unforgettable personalities. Pamuk's puzzles and Borgesian short stories are integral parts of an overall plot which is very suspenseful, compelling, and naturalistic. Whereas Borges is cold and cerebral, Pamuk is deeply humane.

The novel plays with philosophical themes--the purpose of representational art, the relationship between painting and memory, the idea of an artistic style and of originality, blindness and insight, the influence of the West (and cultural influence, in general). With excellent "negative capability," Pamuk avoids taking a position on these issues but instead shows them from many angles. If all these virtues weren't sufficient, My Name is Red vividly represents the unfamiliar world of Istanbul, ca. 1591. And Pamuk makes great use of the modernist device of giving each chapter to a different narrator--all highly unreliable. At the very end, we learn something surprising about the narration of the whole book.

Pamuk has been persecuted by the contemporary Turkish state; he just won a tactical legal victory. The following two claims are both true but are completely separate and independent:

(1) Orhan Pamuk is a hero of free speech whose legal case is important for human rights. (And I say that having spent some six total weeks in Turkey, a country for which I feel a lot of sympathy and fondness.)

(2) Orhan Pamuk is one of the greatest contemporary novelists in the world.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:18 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 1, 2006

a postscript to yesterday

In the schematic that I presented yesterday, one axis was defined by attitudes toward "the state." That's actually too simple. The state can be unitary, hierarchical, and centralized; or it can be decentralized and participatory. Attitudes toward each kind of state can vary from favorable to hostile. Unfortunately, I can't draw a four-dimensional box, but it would be better to show a range of attitudes toward a range of types of government.

My own sympathies lie with governmental bodies--neighborhood commissions, public corporations, advisory boards, public/private ventures, police beat councils, charter schools, problem solving courts, and the like--that address local realities and that allow volunteers to participate. These bodies are better suited to influence culture, which was yesterday's topic. On the other hand, they may also reinforce harmful cultural norms. Federal mandates certainly helped to make local schools and town governments less racist.

I'm just making things as complicated as possible here ....

Posted by peterlevine at 12:04 PM | Comments (2) | TrackBack