« November 2005 | Main | January 2006 »

December 30, 2005

worst and best of America

There's a "challenge to the blogosphere" that's getting a lot of attention: bloggers have been asked to list the Ten Worst Americans of the last 230 years. I find that I am not good at this, partly because I simply don't know as much American history as I should, and partly because I don't pay attention to names and biographies as much as to big social trends and institutions. Thus, for example, I had no idea that Harry Ansliger was the "father" of the War on Drugs, although I recognize that policy as a major part of our past and present. So here is a list of Big Bad Things that Americans have done; each one could have a representative individual's name attached:

1. The Atlantic slave trade and slavery itself

2. The slaughter of Native Americans and the seizure of their land

3. Jim Crow

4. Seccession and the bloody Civil War that followed

5. The Mexican-American War. (I'm very glad that the Southwest is part of the USA, but the conquest was surely immoral.)

6. Occasional waves of political repression, contrary to the Bill of Rights, such as the Alien and Sedition Acts (1798), the Red Scare (1917-1920), the Nisei Interment (1942-5), and the McCarthy Era (1949-54)

7. Self-interested and harmful interventions in weak countries such as Chile, the Dominican Republic, and Angola

8. Massive underinvestment in public spaces and services

9. The flattening of vibrant urban neighborhoods and their replacement with dehumazing modernist designs. (Robert Moses should make the top-ten list.)

10. A coarse popular culture ("popular" around the globe) that glorifies violence

It would be terribly one-sided to list the bad without the good. To balance the above list, here's a Positive Top Ten:

1. The Madisonian system of republican government with ordered liberty that has worked on a large scale for more than two centuries and proved that such a regime is possible

2. A democratic culture in which people are rough social equals, and status (especially inherited status) is relatively unimportant

3. Sustained prosperity born of freedom to innovate, optimism, and public investment in human beings

4. The absorption of waves of "huddled masses," who have not been forced to renounce their diversity

5. The defeat of Nazism

6. Jazz

7. The Civil Rights Movement as a model for nonviolent social change in a modern society

8. The New Deal, especially as embodied in the great mid-twentieth century American cities with their solid systems of health, education, housing, transportation, and recreation

9. Restraint in war and international affairs, especially after the US became a nuclear-armed superpower

10. New York City as the world's cultural capital, especially ca. 1930-1960 as modernism peaked and shifted to post-modernism

The last item is eccentric (although I happen to believe it). There would be excellent reasons for including the Bill of Rights, the Abolition Movement, the Morrill Act, the GI Bill, and the Marshall Plan on the positive top ten.

Posted by peterlevine at 2:58 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

December 29, 2005

the youth vote and the cut in federal student aid

In 2004, about 11.6 million Americans under the age of 25 voted, an increase of about three million compared to the previous election (pdf). Although they broke for John Kerry at the end, young voters were up for grabs, divided about equally among Republicans, Democrats, and independents. Kerry and Bush traded the lead among young voters at least twice during the campaign (pdf, p. 2)

Despite the emergence of this large, energized swing vote, when Congress cut almost $40 billion from the federal budget, $12.7 billion came out of student loans. There are far better ways to cut just as much money from the federal budget, without touching education at all.

So what were the Congressional Republicans thinking? That the youth vote still isn't all that big, compared to the boomers and the retirees? That young people turned out in '04 but will stay home in the congressional elections of '06? That most young voters won't notice the cuts or know whom to blame for them? That college students are really a Democratic constituency? (Note that 41% of college students chose Bush: pdf.) These assumptions are not crazy, but they pose risks for Republicans, who may be applying outdated ideas. In the 1990s, young people were a relatively small group; they tended not to vote; and those college students who did turn out were heavily Democratic. None of this is true anymore. The Millennial Generation forms a large demographic group, seemingly more engaged in politics, and up for grabs. Those are three reasons for incumbent politicians to pay them a little more respect.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:59 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

December 28, 2005

youth-led research after Katrina

My organization, CIRCLE, has made grants to teams of young people who design and conduct community research projects. We are able to make these grants thanks to funding from the Cricket Island Foundation. We also provide the youth teams with some guidance.

Some of our current grantees are a group of homeless youth from New Orleans, who were planning to study the police treatment of their peers (i.e., other homeless young people). Katrina made that research impossible by scattering them across the country. However, they have changed their project to investigate the Katrina experience and its aftermath.

Last week, the Chicago Tribune ran a helpful story on these young people's work. The reporter, Dave Wishnowsky, kindly included some contact information for dispersed New Orleans youth to use if they wanted to be included in the research. The story is entitled "Collecting Katrina memories: Young evacuees plan to write book." You have to register with the Tribune to read the whole story here; but I quote some portions below:

[Matthew] Cardinale, 24, and [Shannell] Jefferson, 21, of New Orleans, are spending this week in Chicago interviewing Katrina evacuees ages 14 to 24 for a project they are hoping to turn into a book."That's what's really unique about this project," Cardinale said about the Hurricane Katrina Evacuee Youth-Led Research Project. "We've got evacuees interviewing evacuees." ...

Cardinale and Jefferson are former residents of Covenant House New Orleans, a homeless shelter for youths.

When Katrina hit in August, Cardinale, a graduate student at the University of New Orleans, was volunteering as a mentor at the shelter. With a $10,000 donation from the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement, he had organized a project for a three-person team of ex-shelter residents, including Jefferson, to research how New Orleans police treated homeless youths.

When Katrina devastated the city, however, the team's plans changed. They decided to instead use the money--plus an additional $7,145 from the same group--to interview young evacuees in Chicago, Houston and New Orleans about their hurricane experiences.

"I think the young people in this whole thing have been overlooked," Cardinale said. "And with this project, this is the first time that a lot of them have had a chance to share their stories. We're giving a voice to so many youths out there, and we're documenting it all."

Posted by peterlevine at 5:04 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

December 27, 2005

privacy and domestic surveillance

Macon, GA: As I wrote recently, I think the biggest question raised by the warrantless surveillance of US citizens is whether the president knowingly authorized criminal acts under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA). I don't know for sure that the acts he authorized were illegal; Orin Kerr says "probably." If they were, it is very disturbing. A criminal law should be a trip-wire that stops powerful people from doing what they want--or even what they think is best. Otherwise, there is no rule of law.

However, a second question is also interesting and important: Is the FISA a good law or not? Should the Act be changed so that the executive branch can conduct certain kinds of domestic surveillance without warrants?

It seems increasingly likely that the administration wanted to scoop up huge quantities of data in order to look for patterns. Perhaps the main goal was not to identify individuals for prosecution or for any other hostile action. Instead, the government may have wanted to draw statistical conclusions from masses of individual data, much as Amazon and Google learn about consumer tastes by aggregating their information about all our searches and purchases. So, for example, the government might be interested in the percentage of foreign calls placed to Afghanistan that are conducted in Arabic. They might want to know how many of those calls mention Osama bin Laden. They would hope to include calls originating from the USA in their statistics. Ultimately, this information might help to identify a terrorist who fit an emerging statistical profile. But it might also be useful for planning a propaganda campaign or a military strategy.

I suspect that the administration did not ask Congress to amend the FISA to permit domestic searches--nor did officials seek retroactive warrants from the FISA Court after they obtained data on US citizens--because the Constitution forbids the vacuuming up of citizens' data without their consent. The Fourth Amendment says:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

No searches or seizures without probable cause--but what probable cause exists when the government harvests masses of statistical data from private phone calls and emails?

Still, the Supreme Court might be persuaded to change its interpretation of the Fourth Amendment. It could say that international phone calls are not "papers or effects." Or it could decide that security threats are so important as to compel some limitations on the Fourth Amendment. After all, "the Constitution is not a suicide pact"; the Bill of Rights cannot be allowed to cause our destruction.

Thus the question is not whether warrantless searches violate Supreme Court precedents, but whether the Court ought to allow them under certain circumstances.

On one hand, we might say that a person's privacy rights are not compromised if the government scoops up vast quantities of data from huge numbers of people and uses the results for statistical research. Only once the government narrows its interest to an individual can there be any direct negative consequences from a search. Only at that point should a warrant be necessary. If the government wants to count the number of times that "Osama bin Laden" appears in my emails, I shouldn't complain. No human being will actually read my mail or even know my name unless something about me triggers suspicion. Then a human being must decide whether to monitor me and should seek a warrant to do so. If my information is only used to develop a profile of "normal" behavior so that terrorists will stand out as abnormal, then I have no grounds to complain.

On the other hand, there are arguments for privacy that count against warrantless domestic surveillance. In a 2003 paper for the Journal of Accounting & Public Policy, I listed 10 reasons why we reasonably care about our own privacy. Some of these reasons apply only (or mainly) to commercial situations, when companies want to collect data about our private behavior for marketing purposes. Below I list the eight reasons that are most relevant to the NSA wiretaps.

1. Limiting the power of the state. A government that can collect information about its own citizens and aggregate it in powerful databases without probable cause will be a very powerful government indeed--a kind of panopticon.

2. Freedom: The main concern here is a "chilling effect." If the government can collect masses of data about our private communications, then we may act cautiously in order to avoid scrutiny, even though we are not guilty of anything. For example, someone might avoid saying "Osama bin Laden" on the telephone, because that could trigger an actual search.

3. Rights of Association: We have both legal and moral rights to associate in voluntary groups. Part of what it means to "associate" is to share information only within the organizations that one joins. Freedom of association may be chilled if the state collects data about our group memberships and combines it with information about our ethnicity, religion, etc. For example, a Moslem might choose not to join a politically radical organization if he knew that the state could find out, because he wouldn't want to contribute to the belief that Moslems tend to be radicals. But he has a right to join any legal association he wants.

4. Property Rights: Perhaps information about me belongs to me, just as anyone's body is his or her property. If this is true, then the state may not collect information from me without my permission (or without probable cause). However, I do not have property rights to all information about me. For example, many people saw me go to the supermarket yesterday and have a right to know what their eyes showed them. So two questions arise with relevance to the NSA. First, are little scraps of private information (such as the destinations of my phone calls) my property? And second, if the NSA puts lots of separate facts about me into a database to create an overall portrait of me, does that violate my property rights?

5. Fair warning: As a general matter, the state is not supposed to interfere in people's private lives without at least letting them know. Normally, a search requires a warrant that the person who is searched can contest. The NSA's wiretaps, however, would be undetectable.

6. Personality Development: Perhaps we need opportunities for private reflection and experimentation if we are to develop complex personalities. We must be able to try out attitudes and values in private so that we can reject them later, without developing a permanent record in someone's secret files. Also, a complex person may act differently in public and private, but this is impossible if there is no private zone. For instance, a teenager should be able to say outrageous things about George W. Bush on the telephone without having to think that his conversation is being monitored.

7. Avoidance of Discrimination: Powerful people sometimes choose to act on the basis of morally irrelevant information. For instance, employers or the state may discriminate on the basis of sexual preference, religious belief, or disability. Laws against such discrimination are difficult to enforce. Therefore, perhaps it is better to prevent powerful people from obtaining prejudicial information in the first place by protecting privacy. This general argument applies to the NSA. If someone is a Moslem, the state has no right to know it, because governments have the power to discriminate on the basis of religion. Furthermore, we may not want the government to develop statistical theories that incline them to be suspicious of particular kinds of people, because discrimination may follow.

8. Happiness: Although there are other moral values besides happiness (consider justice, fairness, compassion, and freedom), we generally think that it is right to make people as happy as possible, at least all else being equal. Furthermore, human beings usually seem happier when they have a zone of privacy, a chance for solitude. Many of us would feel some discomfort if we knew that the NSA was reading our emails, and that is an argument against warrantless surveillance (although it might be outweighed by arguments in favor of security).

Posted by peterlevine at 12:27 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

December 22, 2005

vacation

Today we are flying to Georgia for Christmas. I don't expect to blog again until December 27 or 28. Until then, merry Christmas, happy Hanukah, have a great Kwanzaa, honor the Orthodox Feast of the Nativity, mark the death of the Prophet Zarathustra (December 26), look forward to Lohri, relish the solstice, celebrate Boxing Day, and generally enjoy any excuse for a break.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:01 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

December 21, 2005

a proposal for college reform

Last week, I wrote that it pays for colleges merely to select the most qualified high school students and then put their energy into attracting and retaining famous scholars. They don't actually have to educate their students, because their graduates will succeed anyway. Those admitted to selective institutions are on a track for success at age 18; a college degree will certify their talent and thus give them a big income boost. Parents, students, professors, administrators, and prospective employers have little incentive to worry about how much value the college actually provides though courses. Only the state and the taxpayers have a reason to care.

Here is possible strategy for a college that wants to break the mold:

1. Select applicants who are most likely to benefit from the education that the college offers, based on a whole new admissions process that is not designed to cherry-pick the applicants who are already most advanced at age 18. When students are ready to graduate four years later, evaluate them using a comparable assessment and boast about the "value-added." If a college uses this approach, its SAT scores and average high-school GPA may fall, and then it will sink in the US News and World Report rankings. I would make a virtue of that result and brag about adding value instead of selecting applicants who are bound to succeed.

2. Both during the application process and at graduation, assess students on their ability to address complex, multidimensional problems, ideally in cooperation with others. (My university's Gemstone program is an example.) Set them problems that require a combination of interpretive skills, quantitative analysis, management and communication ability, and strategic thinking. Develop the assessment with input from private-sector employers and civic leaders who can certify that a high score means readiness for work and citizenship.

3. Constantly reform the curriculum and pedagogy to maximize gains for all students on the assessments described above. Perhaps a good approach would be to assign teams of students to address elaborate, multimensional problems over six weeks or longer. Given the same faculty-student ratio and the same faculty work-load that we have today, a college could reassign its professors to interdisciplinary teams that would advise teams of students working on projects. I'm not sure that this is a great idea, but it certainly seems more promising than having professors lecture to huge classes and rely on graduate students to translate their thoughts.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:48 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

December 20, 2005

city of dreaming spires

Oxford--the city, not the university--figures in my memories from all stages of my life. In fact, my connection to the town predates my memory. When I was a colicky baby, my parents rented a house in Oxford one summer that came with its own punt--one of the flat, polled boats that are common on Oxford's two placid rivers. Apparently, I was happy only when lying on my stomach at the bottom of the punt.

When I was between seven and ten, we lived for several long periods in London. My father, a British historian, could make good use of the books and papers in Oxford's Bodleian Library. We took family day-trips to Oxford that developed certain routines. We would go to a pet store in Oxford's Victorian covered market, buy dry food appropriate for deer, and feed them in the park of Magdalen (pronounced "Maudlin") College. The Magdalen park is stocked with short English roe deer and surrounded by a bend in the Cherwell River along which Joseph Addison liked to walk in the 18th century. The gothic towers of Madgalen (ancient and quaint even in Addison's day) rise above the grass and water.

I also remember that we would buy tea in Brown's cafe, which remained remarkably unchanged 15 years later--the same man still made tea by pouring hot water through what appeared to be the same nylon mesh sack. This is where the city's "meter maids" and market vendors met around formica tables to talk in their thick, West-Country accents, straight out of Thomas Hardy.

And it was in the Minoan and Cycladic room of Oxford's Ashmolean Museum that we learned I was color-blind, because I could not distinguish the regions on the map. From the same period, I remember the children's book room upstairs at Blackwell's book shop. It represented a certain style--affluent but bohemian: we would now call it "yuppie"--that was new in England and had not yet reached my home town of Syracuse.

Later, when I was eleven or twelve, my father and I sometimes used to go to Oxford alone. We would meet about every two hours in the anteroom of the New Bodeleian, so that he could check up on me. Between our meetings, I would visit the Pitt-Rivers museum, which I now know to be an extremely eccentric Victorian collection of ethnographic artefacts; or I would buy stamps in a musty stamp shop east of the Cherwell or model train supplies on Broad Street.

Still later, in my teens, we spent two whole summers in or near Oxford. We'd often rent a punt and I'd pole my family along the Cherwell, which seems to run through deep wooded countryside even close to the University. I took a lot of pictures in those days (I had a darkroom back in Syracuse). I'd go in and out of Oxford's colleges looking for good shots of old buildings.

And then, because I won a scholarship that was tenable only at Oxford, I attended graduate school there. I always felt like an outsider to the University, perhaps because I was a graduate student working alone on a dissertation at an institution that revolves around the undergraduate tutorial, or perhaps because I was uncharacteristically shy during that period. Or perhaps almost no one is an insider to Oxford, divided as it is among dozens of colleges and separate academic faculties. In any case, I knew and loved the physical environment, the ancient academic buildings, the bustling modern shopping districts, the old workers' districts, and the farmland of the upper Thames Valley. Needing to take breaks from my writing, I used to walk several times a day. Sometimes I'd just stretch my legs around Addison's Walk or Christ Church Meadow, whose miscellaneous cows munching before a medieval townscape looked like figures in a 17th century Dutch painting. Other days, I'd hike as far as Blenheim or at least to Iffley, where the Norman church still shows its primitive zigzagged carvings

And then, because I won a scholarship that was tenable only at Oxford, I attended graduate school there. I always felt like an outsider to the University, perhaps because I was a graduate student working alone on a dissertation at an institution that revolves around the undergraduate tutorial, or perhaps because I was uncharacteristically shy during that period. Or perhaps almost no one is an insider to Oxford, divided as it is among dozens of colleges and separate academic faculties. In any case, I knew and loved the physical environment, the ancient academic buildings, the bustling modern shopping districts, the old workers' districts, and the farmland of the upper Thames Valley. Needing to take breaks from my writing, I used to walk several times a day. Sometimes I'd just stretch my legs around Addison's Walk or Christ Church Meadow, whose miscellaneous cows munching before a medieval townscape looked like figures in a 17th century Dutch painting. Other days, I'd hike as far as Blenheim or at least to Iffley, where the Norman church still shows its primitive zigzagged carvings

Posted by peterlevine at 10:32 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

December 19, 2005

domestic spying and impeachment

The president's direct order to conduct domestic wiretaps without warrants is a very big deal. I'm ready to change my whole view of the Bush Administration if the facts turn out for the worst. For almost five years, I have been making these arguments:

1. What's bad about the Bush Administration are some of its overt priorities and policies. The way to respond to a public policy that you don't like is to propose a better idea. But who knows what ideas the House Democrats support today--or what Kerry and Edwards wanted to do in 2004? To concentrate on the characters and secret behaviors of men like Bush, Cheney, and Rove is to miss the point of politics, which is supposed to be a contest of ideas.

2. It is also bad political strategy for the Democrats to concentrate on attacking Republican leaders. In times of war or terror, if the conversation dwells on personal characters and behaviors, the incumbents tend to win and the critics look merely opportunistic (especially if they don't have plans of their own).

However, last Friday's revelation of the domestic wiretap order adds a whole new dimension. I don't believe that it alters the two points listed above. The country still needs policy alternatives, especially regarding Iraq. And the Democrats will still be better off if they talk about future directions, rather than attack the President. Nevertheless, to order domestic wiretaps without warrants may violate a federal criminal statute. If a president issues such an order knowingly, operating under the principle that the law doesn't cover his behavior--and he gets away with it--then we don't have limited government or constitutionalism.

Therefore, I think the president should face a congressional investigation to determine whether he knowingly violated § 2511 of 18 USC I(119). If he did, then he should face an article of impeachment. An impeachment debate would be a distraction and would probably energize the Republican base in '06, yet I don't believe the country can ignore possible lawlessness in the White House.

I would not support piling on other charges, such as allegedly lying to the American people about the war in Iraq or presiding over an executive branch that has committed torture. The lying charge is best addressed by voters on Election Day (and I'm not even sure it's true). The torture charge is criminal, but I don't believe it's helpful to make the president personally liable or to try to impeach him. The domestic wiretap order is different because it may have been a direct act by the president himself that violated a US criminal statute. Impeachment is meant for cases in which high officials directly and personally break the law.

The congressional investigation should not be narrowly partisan. It should also explore the role of Congress. If, for example, Nancy Pelosi knew of the illegal order, why didn't she do anything about it? Granted, the administration must have warned her that disclosing the order would be a crime. But the order itself was probably criminal. I don't see the point of congressional oversight if Congress doesn't use its power to oversee.

Impeachment would not be appropriate if the president's orders were simply unconstitutional--for then the appropriate remedy would be to strike them down. Impeachment is for violations of federal criminal law ("high crimes and misdemeanors"). The Bush order does seem to me to be potentially criminal. But--as they say--I'm not a lawyer, and the statute isn't perfectly clear.

The law makes wiretapping illegal except under certain circumstances, which include "a certification in writing by a person specified in section 2518 (7) of this title or the Attorney General of the United States that no warrant or court order is required by law, that all statutory requirements have been met, and that the specified assistance is required ..." The President received such a certification from the Attorney General. But was the certification valid? The AG had to find that domestic wiretaps met "all statutory requirements." The statute bans wiretaps without a warrant. Thus, it seems to me, the only question is whether section (2)(f) creates a loophole that would allow a certification. That section says, "Nothing contained in this chapter ... shall be deemed to affect the acquisition by the United States Government of ... foreign intelligence activities conducted in accordance with otherwise applicable Federal law involving a foreign electronic communications system." Whether this section creates a loophole depends on whether the domestic communications that have been intercepted under Bush have always used "a foreign electronic communications system"--whatever that phrase may mean in the age of the Internet.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:25 AM | Comments (3) | TrackBack

December 16, 2005

college teaching isn't very effective

Yesterday's post was long and meandering. I was thinking as I wrote about several different (but related) topics. I'm beginning to plan a speech that I'll give in Texas in January, and yesterday's post was preparatory. Anyway, I think I "buried the lead." If anything I wrote was interesting, it was this paragraph:

College students score higher on tests of knowledge and critical thinking near the end of their undergraduate careers than at the beginning. The best estimates suggest that college exposure has a positive effect--between one quarter and one half of a standard deviation, depending on what outcomes we measure. However, there is remarkably little evidence that the type of college matters, even though colleges differ extraordinarily in size, selectivity, and mission. To me, this finding suggests that little of what a college does intentionally to educate students has an impact. Students grow, in part thanks to the college experience (which includes extracurricular activities and living arrangements); but they do not benefit to an impressive degree from college teaching.

As Hellmut Lotz noted in his comment yesterday, "course work provides valuable focus to the learning experience in dorms and friendship circles. If young adults went to ... day care [for a year], they would probably learn less." I agree. Students benefit from being congregated with other students in institutions supposedly dedicated to learning. Even the title of "student" probably has a positive effect. Nevertheless, the direct impact of the instruction that colleges offer seems remarkably small, given how much we charge for it. I blame large classes, unhelpful exercises, poorly prepared and motivated teachers, and inappropriate curricula--but the underlying problem is the incentive structure that I described yesterday. Neither colleges nor students have enough reason to care about the "value-added" from higher education.

The source, again, is Ernest T. Pascarella and Patrick T. Terenzini, How College Affects Students: Vol. 2, A Third Decade of Research (Jossey-Bass, 2005), p.145-6; 205-6.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:55 AM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

December 15, 2005

why schools and colleges often overlook civic development

Markets may have advantages for education, but they pose special problems for civic education. The civic development of young people will be undervalued in any market system, unless we take deliberate and rather forceful efforts to change that pattern.

The degree to which markets govern education varies according to the type of institution. At one extreme, competitive research universities fight tooth-and-nail for faculty and students who have enormous choice about where to work or study. Community colleges and local universities are somewhat more insulated from markets, although they do compete with more distant institutions, for-profit colleges, and the workforce. Independent private schools compete fiercely for students, less so for faculty. Charter schools and schools funded by public vouchers have been deliberately placed in markets in which parents are the "consumers." Finally, even a large, standard, urban public school system is in a kind of market. To the extent that parents have resources, they can choose to move away or to enroll their children in private or parochial schools. Likewise, public school teachers often have some degree of choice about where to work.

To see why the market undersupplies civic education, consider what parents want schools and colleges to do for their own children. First, they may want their children to learn the skills, values, and knowledge necessary to be good citizens who can keep track of public issues, deliberate with others, build consensus, and take appropriate action. In a 2004 poll, 71% of adults said that it was important to "prepare students to be competent and responsible citizens who participate in our democratic society" (pdf).

It benefits everyone if these attributes are widespread. However, if most people are good citizens, then it doesn't matter much whether one's own kid has civic skills and values: he or she will benefit anyway. And if most people are not prepared for active and responsible citizenship, then there is not much that an individual can do to improve a democratic society. Thus there are reasons for parents--and their children, once they enter adolescence--to make civic education a low priority. I heard a teacher in a focus group say that if you ask parents whether schools have a civic mission, they will agree, because they know it's the right thing to say. But they really want their own kids to get an education that will help them to get ahead; "civic education is for other people's kids."

We know that parents want their children to gain marketable skills that will increase their economic security. Eighty-one percent of adults endorsed "preparing students for the workforce and employment" as a top goal of schools. Such skills are especially valuable in a highly competitive, global "knowledge economy" that changes rapidly. We know from survey data and qualitative research that young people are increasingly aware of the need to amass "human capital" (marketable skills). It is good for the whole community and nation if such skills are widespread, but human capital also benefits each person who possesses it. Therefore, parents and kids alike are motivated to obtain skills with economic value.

Third, parents may want their kids to obtain markers of economic value, quite apart from any actual skills. A college degree is worth a lot of money, especially if it is a degree from a competitive, prestigious institution. The degree would be economically valuable even if the graduate did not know much of value.

College students score higher on tests of knowledge and critical thinking near the end of their undergraduate careers than at the beginning. The best estimates suggest that college exposure has a positive effect--between one quarter and one half of a standard deviation, depending on what outcomes we measure. However, there is remarkably little evidence that the type of college matters, even though colleges differ extraordinarily in size, selectivity, and mission.* To me, this finding suggests that little of what a college does intentionally to educate students has an impact. Students grow, in part thanks to the college experience (which includes extracurricular activities and living arrangements); but they do not benefit to an impressive degree from college teaching.

One aspect of the "college experience" (and also the k-12 experience) is exposure to other kids. This is a fourth goal that parents may have: to enroll their own children with other students who are on track for economic success. Peers can provide valuable networks and role models. Thus parents may want their students to attend selective institutions, regardless of educational quality.

Now consider the same issue from the perspective of a college or a k-12 school that has some control over student admissions and other policies. (And remember that even a standard public school system may compete with neighboring systems for students and faculty.) The easiest way for such institutions to satisfy the market is to pay some lip service to the cause of civic education--since most parents say they want other people's kids to be good citizens--but to focus all serious resources on developing students' marketable skills.

Furthermore, for some important institutions, it is easier to provide markers of economic value than actually to add value. If an institution can become highly competitive and admit only the best qualified applicants, then its students will gain a reputation for being desirable employees regardless of what they learn in the institution. Essentially, the admissions office will provide a service that is worth a lot of money to successful applicants, by selecting the few who are most marketable. If the admissions office can make someone wealthy simply by admitting him, then there isn't much pressure to educate him once he matriculates. The pressure is greater in k-12 schools, but even there, success can be guaranteed if a school is able to admit only a small percentage of applicants. Even a public school system can achieve high rates of success without a lot of effort if many privileged families choose to live within its boundaries.

Meanwhile, schools and colleges must try to attract the best qualified faculty--in part because that is a way to increase their attractiveness to potential parents and students. In a competitive market for teachers (especially at the college level), an institution can offer its faculty light teaching loads and lots of time to concentrate on research that is valued inside their disciplines. If an institution puts pressure on its faculty to enhance students' skills, then the most successful professors can avoid the pressure by simply leaving. That is especially true if they are asked to enhance students' civic skills, values, and knowledge, because the academic disciplines do not value these outcomes. In turn, the departure of well-known faculty can make an institution less desirable to students; and a decline in the number of applicants will cause a university to fall in the U.S. News & World Report ranking. A vicious cycle ensues. A similar pattern can occur in any k-12 institution that must compete for students--including urban public school systems that compete with nearby suburbs.

One response to this very basic problem is to emphasize that civic education is actually a "private good" for individual students. Parents should value it for their own children because:

(1) the same skills that are useful for civic participation (consensus-building, working with diverse people, addressing common problems) are also increasingly valuable in the 21st-century workplace;

(2) students who engage in their communities while they attend school and college may feel better about school, gain confidence and motivation, and therefore have a better chance of achieving educational success; and

(3) civic participation arises from human relationships and obligations that can be intrinsically fulfilling.

In my view, there is insufficient research evidence for these points, although they are plausible. Moreover, if schools and colleges provide service-learning opportunities and other forms of civic education because of their potential private benefits for students, they may not achieve good civic outcomes. Convergent research from numerous studies shows that civic outcomes require intentionality on the part of instructors and institutions.

Perhaps we can make some limited progress if we challenge ranking systems like the one sold by U.S. News & World Report, because it uses selectivity as evidence of excellence. That method does not reward institutions for educating their students. Alternative rankings, such as Washington Monthly's College Guide, at least give applicants and their parents the opportunity to consider institutions' impact on students (including their civic impact). Likewise, measuring the civic outcomes of k-12 schools might somewhat change the way that parents and taxpayers evaluate these institutions.

However, I think that the problem outlined here is fundamental and cannot be solved merely by providing alternative rankings and assessments (in a word, information). In a decentralized system, public goods tend to be under-supplied. Civic participation is a public good. An outside power, probably the government, must apply leverage to change the priorities of schools and colleges.

*Ernest T. Pascarella and Patrick T. Terenzini, How College Affects Students: Vol. 2, A Third Decade of Research (Jossey-Bass, 2005), p.145-6; 205-6.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:11 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

December 14, 2005

an aesthetic question

Why does a distant mountain often look beautiful? It is a simple shape, maybe an inch high if you look at it next to your hand--not unlike a mound of grass-covered earth that's a few feet away, or even a pile of laundry. Yet a mountain is much more likely than those things to be beautiful.

One answer: Human vision is not the perception of a flat field of shape and color, composed of little reflections on our retinas. It is a thoroughly interpretive act. We see the mountain differently from a pile of clothes because we know that the mountain is far away. The space between the viewer and the object is part of what we see. But why should we appreciate a large volume of empty space? Perhaps because we interact with it in our imaginations. We feel a potential to move freely through the space or to "conquer" the mountain by climbing it.

Another answer: Human perception is thoroughly interpretive, and we have learned to value mountains. They are God's work; they are humbling creations of Nature; they are sublime. Supposedly, Petrarch was the first European since antiquity to appreciate outdoor views. Five hundred years later, we have absorbed positive evaluations of landscape. But that appreciation was absent in 12th-century Europe and might not exist in some current cultures. It might be possible for a culture to learn to love the sight of small mounds of earth.

What about pictures of mountains? They are just flat fields of color. Perhaps we enjoy them because we are able to derive the same experiences from them that we take from real mountains.

Also, we appreciate representation itself. A picture of some objects on a table can be as beautiful as a landscape painting of a huge mountain; but the mountain itself will be more beautiful than any set of plates and food. A picture of a mountain may be beautiful even if it is so stylized or abstract that we cannot imagine ourselves entering the space depicted in it. These examples show that it is often the feat of representation, rather than what is represented, that matters in art. In that way, the aesthetics of art and of nature seem fundamentally different.

Posted by peterlevine at 3:08 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

December 13, 2005

E-Rulemaking

For every law passed by Congress, executive branch agencies write some 25 regulations. All proposed regulations are now being presented on one site--regulations.gov--built under a very handome contract from OMB. The potential advantages of bringing the regulatory process online cannot be overstated (and I'm the opposite of a technological optimist). There may be no worse flaw in our democracy than the current system. The existing rulemaking process creates the following problems:

1. It favors organized lobbying groups that can hire experts. Those experts become part of the same "community of practice" or the same "stakeholder group" as the regulators. They have similar training and networks; they know the ropes; and over the course of their careers, they work for the same employers. As a result, they get very cozy. Some "public interest" groups, such as the major environmental organizations, have fought their way into the circle. But other interests, such as the homeless and even average taxpayers, are not effectively organized to lobby scores of separate rulemaking bodies.

2. A system of administrative rulemaking encourages Congress to pass vague laws that fail to resolve tensions and tradeoffs. Congress kicks those hard issues to rulemakers, who have relatively low profiles and are insulated from public accountability. For instance, various statutes since the Federal Communications Act of 1934 have directed the Federal Communications Commission to issue broadcast licenses in such a way as to serve the "public interest, convenience, and necessity." Likewise, Congress has delegated the right to "determine just and reasonable rates" to the Federal Power Commission; and the authority to "prevent an unfair or inequitable distribution of voting power among security holders" to the Securities and Exchange Commission. Congress has not even attempted to define "just rates," the "public interest," or "unfair voting power." When regulators make costly or unpleasant decisions in the course of implementing vague statutes, legislators win political points by blaming them.

3. Rulemakers obtain no legitimacy from being elected, but they do have expertise in science, law, or economics. Thus they have a natural tendency to make moral decisions appear to be technical ones. If appointed administrators ever presumed to set "reasonable rates" for power, or picked broadcast companies because of the quality of their programming, their decisions would appear overly "political." Therefore, rulemakers typically address such questions as if they were technical matters of efficiency, even though these issues are fundamentally moral.

4. As a result of a system in which multiple agencies make separate decisions on supposedly technical grounds, federal policy is unnecessarily complex. The great and increasing complexity of policy is a barrier to democratic participation.

5. Whereas Congress can only consider a major area of policy once every few years, administrative agencies can reconsider them constantly. The result is a mass of always shifting rules. But, as Madison wrote (Federalist 62), "mutable policy ... poisons the blessings of liberty itself." Government by the people can hardly be said to exist, he said, "if the laws be so voluminous that they cannot be read, or so incoherent that they cannot be understood; if they be repealed or revised before they are promulgated, or undergo such incessant changes that no man, who knows what the law is today, can guess what it will be tomorrow."

6. Administrative rulemaking leads to piecemeal, incoherent policy, as multiple agencies make decisions basically in isolation.

7. Administrative rulemaking undermines the Constitutional order itself. Locke proposed that "the legislative cannot transfer the power of making laws to any other hands. For it being but a delegated power from the people, they, who have it, cannot pass it over to others." (Second Treatise of Civil Government, chapter 11, §141.) This precept was made explicit in the Constitution, which assigns "all legislative powers" to Congress. In reality, however, most binding rules are made by administrative agencies.

I actually favor a rather radical solution: treating vague laws as unconstitutional. However, this isn't going to happen. Surely a partial remedy would be to turn the process by which people file "comments" on proposed regulations into something approaching public deliberation. Why not make all pending regulations easily searchable on a single web page, allow people to comment and read one another's comments, and thereby promote an equitable public dialogue?

Indeed, that is the purpose of regulations.gov. However, in a comment filed more than one year ago (pdf), the great people at Information Renaissance criticized the emerging website on numerous crucial grounds. A few complaints stood out for me: There was no opportunity to create conversational "threads"--each comment just stood alone. There were no links to important background materials. The page didn't use open standards so that others could build software compatible with it. The search engines weren't effective. The process for designing the site was itself closed--it wasn't even easy to find out what contractor was responsible for it. And there was no easy means to get automatic updates of new regulations.

As far as I can tell, none of these problems have been solved. I don't believe that the current site will change much. It will make it somewhat easier to find regulations--but only people with salaries and training for the purpose will look regularly. It will allow people to comment with a single click--but most people cannot do so effectively.

The great advantage of an online forum is the potential for citizens to benefit from other citizens' work. For example, someone should be able to summarize a complicated regulation in a way that brings out its bad consequences, and then others should be able to refine, criticize, endorse, or disseminate that summary. The current structure does not support such work at all.

[Note: some of the above is auto-plagiarized from my book The New Progressive Era.]

Posted by peterlevine at 11:29 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

December 12, 2005

Schelling's Nobel speech

Our colleague Tom Schelling received the Nobel Prize on Saturday, so many of us in the Maryland School of Public Policy gathered in our common space this morning to watch the ceremony.

Schelling's speech was a forcefully ex temporized expansion of this essay. He begins, "The most spectacular event of the past half century is one that did not occur. We have enjoyed fifty-eight years without any use of nuclear weapons." That streak would have seemed unimaginably lucky to people in 1945 or 1950. In 1960, C.P. Snow declared it a "mathematical certainty" that thermonuclear war would erupt within a decade unless the superpowers disarmed completely and immediately.

And yet the nuclear powers have passed up opportunities to use nuclear weapons. The U.S. famously avoided using the A-bomb in Korea, although Schelling believes that we would have used nuclear artillery had the Chinese invaded the little island of Matsu. Israel refrained from using nuclear weapons against two advancing Egyptian armies that were massed in the desert (away from civilian populations) in 1973. The Soviet Union avoided using nuclear arms in Afghanistan, even though the alternative--bombing from low altitudes for accuracy--cost them so many aircraft that they lost the war. The Soviets also (in a sense) refrained from using nuclear weapons in WWIII. That is, even though their official military doctrine held that war in Europe would automatically turn nuclear, they nevertheless built up a huge conventional military that would have been a complete waste if the doctrine were true. This is evidence that they expected both sides to fight with conventional weapons and to sit on their nuclear stockpiles.

The reason for all this restraint is a nuclear "taboo." John Foster Dulles saw the taboo forming in the 1950s and considered it an obstacle. He decried the "false distinction" between chemical and fissile weapons. Soon thereafter, Eisenhower declared that the United States would treat nuclear weapons as available and "conventional" in times of war.

But no one actually used nuclear weapons after Nagasaki. The taboo became strongly established. In 1964, President Johnson said, "Make no mistake, there is no such thing as a conventional nuclear weapon. For 19 peril-filled years no nation has loosed the atom against another. To do so now is a political decision of the highest order." The 19 peril-filled years have now lenghtened to 60.

Schelling believes that Hiroshima and Nagasaki have acquired a "biblical" significance, an almost religious horror (even though, while he didn't say this in his lecture, more people died in other nights of bombing during WWII). The aura of Hiroshima was felt even by the Soviet generals who ran the Afghan war. Schelling is convinced that the Pakistanis and Indians feel it, too; their motives for building nuclear arsenals are deterrence, status, and influence, but they do not expect ever to use their bombs.

Whether the Iranians and North Koreans feel the force of the nuclear taboo is another question. Schelling argues that any nation that uses nuclear weapons should know that it will be reviled by the world and perhaps even denied sovereignty by the rest of the world. Presumably, if this is a true taboo, then the revulsion should arise even if the use of nuclear weapons isn't very deadly--for example, if they are used against an isolated bunker or a ship at sea. We need the taboo because we have an unimaginable amount to lose if an enemy decides that fissile explosions are just as acceptable as chemical ones.

Schelling laments the Senate's failure to ratify the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty in 1999 as a missed opportunity to strengthen the taboo--to say that nuclear weapons "are under a curse; we don't even want them tested." The United States should also play down its interest in developing new forms of nuclear weapons. "Our strongest hope to avoid having nuclear weapons used against any of us, Swedes or Americans, is to have countries like Iran and North Korea know that ... any use of nuclear weapons will be severely castigated." We want the Iranians to view nuclear weapons as a tool for deterrence that they can never actually use. We will be the ones deterred if the mullahs have nukes, but we can live with that.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:29 AM | Comments (3) | TrackBack

December 9, 2005

a political strategy

At a meeting earlier this week, a colleague proposed a political strategy that I will summarize here, even though I find the implications at least somewhat disturbing. He said that if you want to change educational policies, you must change public opinions about schools. (By the way, a parallel analysis would apply to welfare or crime.) Most Americans live in major metropolitan areas whose news media emphasize what happens in the central cities. Therefore, coverage of--and debate about--the 50 biggest urban schools systems is the basis on which Americans form their opinions about education, writ large. Most people's own kids are not in those urban schools, but they are satisfied with their own childrens' education. To the extent that they care about education as a public issue, they are thinking about the 50 biggest urban school systems.

Thus, to change their opinions, you have to change news coverage and editorial commentary related to the top 50 school systems. One approach might be to influence the news media itself. I recently heard that the Student Voices program measurably changed Philadelphians' attitudes toward urban youth by putting young citizens on TV in highly responsible roles. However, in the long run, there is probably no substitute for changing the actual policies, priorities, and outcomes of schools.

Which brings us to the final step of my colleague's argument ... Who has power over the large public schools systems and other public institutions? Not elected officials, and not professionals. (Teachers and other education professions have largely fought standards-and-accountability reforms for 20 years and consistently lost.) The people who decide what happens in urban public schools and other urban institutions are a finite group in each city that consists of major developers, a few elected officials, major employers, union leaders, sometimes the heads of local colleges and universities, and sometimes some local civil rights leaders who have fought their way to the table. They all know one another. Apparently, except in San Francisco and Washington, DC, there is literally a room or building where they meet and the key decisions are made.

The conclusion, which I certainly want to resist, is that changing national policies and priorities in education really comes down to changing the opinions of about 25 people (mostly business leaders) in each of about 50 major American metropolitan areas.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:23 PM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

December 8, 2005

what's wrong with torture?

For anyone who wonders why torture is wrong, an excellent argument can be found in David Luban's "Liberalism, Torture, and the Ticking Bomb," Virginia Law Review, vol. 91 (Oct. 2005), pp. 1425ff. Here I'll paraphrase a central part of the argument.

While there are no major ancient or medieval critiques of cruelty, the classical liberals (who were the intellectual ancestors of today's conservatives and progressives alike) focused on cruelty as a special evil because it represented what they feared most: state tyranny. Killing someone can cause more harm than torturing him. Throwing someone in jail for the rest of his life can be worse than inflicting a medium amount of pain. Nevertheless, the torturer is a perfect representative of a tyrannical state--more so than the executioner or the jailor. Luban p. 1430:

the self-conscious aim of torture is to turn its victim into someone who is isolated, overwhelmed, terrorized, and humiliated. Torture aims to strip away from its victim all the qualities of human dignity that liberalism prizes. The torturer inflicts pain one-on-one, deliberately, up close and personal, in order to break the spirit of the victim--in other words, to tyrannize and dominate the victim. The relationship between them becomes a perverse parody of friendship and intimacy: intimacy transformed into its inverse image, where the torturer focuses on the victim's body with the intensity of a lover, except that every bit of that focus is bent to causing pain and tyrannizing the victim's spirit.

Some people argue that torture is nevertheless necessary in a society threatened by people who are willing to detonate nuclear bombs in crowded cities. What about the "ticking time bomb"--the terrorist who must be forced to divulge his secrets before there's a big explosion? Shouldn't he be tortured to save innocent lives, much as Dirty Harry forced Scorpio to reveal where he'd hidden the kidnapped child in the eponymous 1971 movie?

There are two major responses. First, real life doesn't present ticking-time bomb situations, and even if it did, torture wouldn't work to divulge the necessary information, because terrorists can lie. In real-life situations, torturers try to extract whatever information they can from suspected enemies, hoping to gather data that strengthens their overall understanding of enemy networks. No single suspect holds secrets that can by themselves save lives. It follows that a strategy of torture will require lots of it.

In any case, you cannot torture just once in a while. Torture that has any chance of working must be professionalized. The state needs experienced (desensetized) torturers, torture manuals, torture training, torture equipment, and lawyers' memos rationalizing torture. The effect of all this "infrastructure" is not only to generate a new part of the government that will fight for its own survival. Worse, it tends to "normalize" torture. Normalization is a powerful and dangerous pyschological phenomenon. As Luban writes (pp. 1451-2):

we judge right and wrong against the baseline of whatever we have come to consider "normal" behavior, and if the norm shifts in the direction of violence, we will come to tolerate and accept violence as a normal response. The psychological mechanisms for this re-normalization have been studied for more than half a century, and by now they are reasonably well understood. Rather than detour into psychological theory, however, I will illustrate the point with the most salient example .... This is the famous Stanford Prison Experiment. Male volunteers were divided randomly into two groups who would simulate the guards and inmates in a mock prison. Within a matter of days, the inmates began acting like actual prison inmates--depressed, enraged, and anxious. And the guards began to abuse the inmates to such an alarming degree that the researchers had to halt the two-week experiment after just seven days. In the words of the experimenters:The use of power was self-aggrandising and self-perpetuating. The guard power, derived initially from an arbitrary label, was intensified whenever there was any perceived threat by the prisoners and this new level subsequently became the baseline from which further hostility and harassment would begin... . The absolute level of aggression as well as the more subtle and "creative" forms of aggression manifested, increased in a spiralling function.It took only five days before a guard, who prior to the experiment described himself as a pacifist, was forcing greasy sausages down the throat of a prisoner who refused to eat; and in less than a week, the guards were placing bags over prisoners' heads, making them strip, and sexually humiliating them in ways reminiscent of Abu Ghraib.

I think we should be very careful about any behavior that is not unjust in itself but that can escalate quickly and without natural limits. That is why imprisonment is better than corporal punishment. Ten years in jail is a worse punishment than a dozen lashes. However, an excessive prison term can be reconsidered before it is served, and there is a natural limit to imprisonment (a life sentence). There is no limit to the number of lashes inflicted inside of an hour. That is why the state should never be allowed to inflict deliberate pain, even if we believe that it may deprive people of life and liberty.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:08 AM | Comments (3) | TrackBack

December 7, 2005

texture

Yesterday, 6:00 am: In a dark house with a sleeping family, unable to rest myself, I'm working on a proposal to the National Science Foundation.

8:30 am: The Metro train is jammed because everyone is large in their winter coats. It's too tight for newspapers, so people stare vacantly at one another.

9:30 am: In a conference room on K Street, overlooking a square with trees that are sugared by the season's first snow. Bright light streams through the huge panes. Eight people sit around a large conference table talking about the appropriate "message" for a nonpartisan political campaign. The short speeches begin with self-deprecating jokes, but everyone seems fundamentally self-assured and experienced.

11:30 am: In another conference room, 6.5 miles northeast of K Street. This one is windowless and crowded. The walls are decorated with binders. We are going over the budget of a nonprofit organization. The institution itself is prospering, but the broader trends--lots of kids to serve, impending cuts in federal spending--make us sober.

4:00 pm: In our front yard with our 6-year-old, building a foot-high "snowman" out of powdery snow as the clear sky turns dark blue behind a lattice of tree limbs. Venus and a slender moon appear over the roofs; commuters crunch home.

10:00 pm: Back to the NSF proposal and email, but there's time for cookie and tea with my wife and teenager and then a few pages of Orhan Pamuk's My Name is Red.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:15 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

December 6, 2005

on McCain in '08

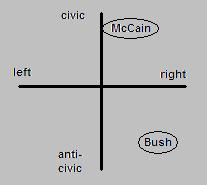

The other candidates, including all the Democrats, are going to have to show why they're preferable to John McCain in 2008. McCain takes positions to my right on certain issues, notably abortion. However, I am not yet convinced that Democrats have a serious plan for moving the country to the left on the economic issues that matter most to me. A "serious plan" would not only include a plausible policy idea--I guess John Kerry's health plan qualified as that--but also a way of paying for the idea and a strategy for enacting it. Kerry had neither.

In any case, there is a dimension of politics that is orthogonal to the left/right spectrum (which is itself a crude representation of our values). This orthogonal dimension measures our civic condition, broadly understood. To improve civic affairs would require procedural changes, such as campaign finance reform and a better system for drawing electoral districts. It would also require a different kind of leadership, one that put genuine issues and choices before the public and scorned name-calling and character assassination.

For my own part, I'd like to see the country move somewhat west on this chart and as far north as possible. Bush is way over east, although not consistently so. The real shame is how far south he has taken us. McCain has the potential to move us northward, and that is a promise that others will have to work hard to surpass, in my opinion.

Posted by peterlevine at 6:48 AM | Comments (3) | TrackBack

December 5, 2005

quiz

For one free annual subscription to this blog, what is wrong with the following passage from a front-page article in the Sunday New York Times? "Mr. Valdéz, a k a La Barbie, does not look like a monster. He gets his nickname, the authorities said, because he has the light complexion and blue eyes of a Ken doll."

Posted by peterlevine at 7:18 AM | Comments (5) | TrackBack

December 2, 2005

effects of faculty ideology

In the debate about the alleged liberal bias of universities, some people say that it doesn't make any difference if most professors are left-of-center, because most of their students soon become moderates or conservatives. In other words, professors' political opinions have little impact.

Indeed, the impact of faculty can easily be exaggerated. Students form their own opinions, and to the extent that they are influenced by others, professors are by no means the most important guides. Peers, parents, clergy, and the mass media almost certainly have more impact. Nevertheless, longitudinal survey data show that the ideology of a given college's faculty affects its students, even if we hold constant undergraduates' attitudes when they enter.

The "political climate" of a college, measured in terms of average student opinions and average faculty opinions, has significant and consistent effects on individual undergraduates, influencing their likelihood of voting, their commitment to social activism, and their views on a wide range of contested current issues from the death penalty to taxation. The effects of faculty and peers are independent; the peer effects are considerably bigger. Sometimes, studies find that the peer effects completely negate the faculty effects. However, it may be that liberal students elect to attend certain colleges because their faculty have a reputation for being liberal. Then peer effects would reflect faculty effects.

Incidentally, having a liberal faculty is also associated with increases in students' interests in the arts.

Pascarella and Terenzini find that "Participation in racial or cultural awareness workshops and enrollment in ethnic or women’s studies courses, for example, are both likely to nudge students' political orientations toward the left side of the liberal-conservative political spectrum and increase their support for social activism."

Students in private colleges and selective colleges are most likely to change their opinions in a liberal direction. (This finding is based on measures of attitudes toward a few policy issues.)

Source: Ernest T. Pascarella and Patrick T. Terenzini, How College Affects Students: Vol. 2, A Third Decade of Research (Jossey-Bass), pp. 286, 294-5, 292 306, 294.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:35 AM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

December 1, 2005

"privatizing the neighborhood"

In several books and articles, my colleague Bob Nelson has made an interesting proposal that he neatly summarizes in a new Forbes Magazine column (Robert H. Nelson, "Privatizing the Inner City," Dec. 12). I would rephrase his argument as follows:

1. Older cities have a disadvantage in attracting new development and investment, because their land is divided into small, individually held parcels. If there is a plan afoot to redevelop a district, each landowner can refuse to participate, either because he wants to extract a high price or because he holds a principled objection to the redevelopment. Investment therefore flows to the exurbs where there is wide-open land and no one can veto a plan.

2. Like other old cities, New London, CT, tried to avoid this problem by using eminent domain, a power that the Supreme Court upheld last June. But many people were outraged by the Court's decision, and the U.S. House has already passed a bill to restrict the use of eminent domain for economic development. Indeed, New London's tactic was a troubling exercise of state power--one often used in the interests of gentrification and to the disadvantage of poor residents.

3. There is an alternative. An existing urban neighborhood could be allowed to become a homeowner's association if a super-majority of its residents filed a petition to that effect. The association would gain ownership of the streets and other public facilities. The city would cease providing certain services, such as street cleaning, but the association would buy those services on the market. It would be governed by an elected board with considerable power. Among other things, it could decide to sell the whole neighborhood to a developer and divide the profits among the owners. This is what the residents of Sursum Corda, a public housing project in DC, have decided to do--taking $80,000 per unit as proceeds from the sale of the whole development. Alternatively, the association could allow portions of its neighborhood (such as open spaces or blighted lots) to be developed and then put the profits to common use.

More than half of all new American homes are built in homeowners' associations that collectively own the streets and public facilities, that are governed by majority-rule, and that exercise enormous power over each owner. Most of these community associations are new suburban developments. The association is formed before anyone moves in. Nelson's innovative proposal is to allow associations to be formed in existing urban neighborhoods.

Forbes has entitled Nelson's piece "Privatizing the Inner City." Nelson is something of a libertarian (who once included me in a Liberty Fund conference on homeowners' associations). However, the political valence of his proposal is not straightforward. An orthodox libertarian would not like Nelson's idea because it allows a super-majority to override individuals' rights, thanks to a law. Nelson ends his piece with this analogy: "In the 1930s the Wagner Act provided for collective bargaining between newly organized workers and businesses. Today we need a new Wagner Act that will enable collective bargaining between neighborhood property owners and developers." I can't believe that most Forbes readers admire the Wagner Act. But liberals and leftists ought to give Nelson's proposal a serious look.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:02 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack