« August 2010 | Main | October 2010 »

September 30, 2010

what our social studies teachers think

The American Enterprise Institute has released a new survey called "High Schools, Civics, and Citizenship: What Social Studies Teachers Think and Do." I know four of the authors and respect their work in general as well as this particular survey.

Ideology is inescapable when we consider civic (a.k.a. political) education. AEI is generally seen as a conservative organization, but that does not mean that the report is biased or designed to reach conclusions convenient to conservatives. On the contrary, it rebuts the kind of sharp conservative critique represented by Chester Finn and colleagues in a 2003 Thomas B. Fordham Institute report entitled Where Did Social Studies Go Wrong?. Finn claimed that students emerged "from K-12 education and then, alas, from college with ridiculously little knowledge or understanding of their country’s history, their planet's geography, their government's functioning, or the economy's essential workings." The underlying problem, he asserted, was that social studies teachers had bad values. By the year 2001, he wrote:

- in the field of social studies itself, the lunatics had taken over the asylum. Its leaders were people who had plenty of grand degrees and impressive titles but who possessed no respect for Western civilization; who were inclined to view America’s evolution as a problem for humanity rather than mankind’s last, best hope; who pooh-poohed history’s chronological and factual skeleton as somehow privileging elites and white males over the poor and oppressed; who saw the study of geography in terms of despoiling the rain forest rather than locating London or the Mississippi River on a map; who interpreted ‘civics’ as consisting largely of political activism and ‘service learning’ rather than understanding how laws are made and why it is important to live in a society governed by laws; who feared that serious study of economics might give unfair advantage to capitalism (just as excessive attention to democracy might lead impressionable youngsters to judge it a superior way of organizing society); and who, in any case, took for granted that children were better off learning about their neighborhoods and ‘community helpers’ than amazing deeds by heroes and villains in distant times and faraway places.

This assertion was not based on any data whatsoever. In contrast, the new AEI survey finds:

- 83 percent of the teachers surveyed [see] the United States as a unique country that stands for something special in the world. At the same time, 82 percent of survey respondents say students should be taught to 'respect and appreciate their country but know its shortcomings.' Despite all of the concerns about anti-American sentiment in schools of education, just 1 percent of teachers want students to learn 'that the U.S. is a fundamentally

flawed country.' This sounds, to our ears, like a near pitch-perfect rendition of what parents, voters, and taxpayers would hope for--schools where students learn that America is exceptional even as they learn about its failures.

In the AEI survey, 60% of teachers think it is "absolutely essential" to teach students to "follow rules and be respectful of authority." Many fewer (37%) think it's absolutely essential to teach students "to be activists who challenge the status quo of our political system and seek to remedy injustices." Four out of five consider it absolutely essential to know the components of the Bill of Rights and to have "good work habits such as being timely, persistent, and hardworking." One in five think that education professors are overly critical of the US; eight percent think those professors are overly appreciative.

The AEI results are consistent with our own finding that many more young Americans recall studying "great American heroes and virtues of the political system” than "racism and other forms of injustice.” I don't necessarily object to the balance that exists in most American classrooms, but I do think leftists critics have more empirical basis for their complaints than conservatives have. If the ideological valence in our schools is wrong, it's not that students receive an overly cynical account of American history but rather than real injustices are ignored.

On most of the questions about values and goals, public school and private school teachers respond similarly. But their actual practices are different. For example, 86% of private school students say they expect their students to keep up with the news, compared to 44% of public school teachers. That could be in part because laws and policies that govern public schools make no place for current events. Forty-five percent of public school teachers in the survey--but only 9 percent of private school teachers--say that "social studies has been deemphasized" because of No Child Left Behind.

Posted by peterlevine at 1:48 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

September 29, 2010

educating youth for better politics

That is the title of today's blog post. The text is not here but on the Huffington Post. I co-wrote it with Scott Warren and Alison Cohen of Generation Citizen, and it's about the civic achievement gap in high schools.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:11 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

September 28, 2010

book talks on civic engagement

This fall, please join these four authors for discussions of their new books.

Sept 9, Noon-2 pm, Rabb Room, Lincoln Filene Hall

Henry Milner

The Internet Generation: Engaged Citizens or Political Dropouts

Tufts University Press, 2010

Henry Milner is a political scientist at the University of Montreal in Canada and Umeå University in Sweden, and co-editor of Inroads, a Canadian journal of policy and opinion

Oct. 13, 4:30-6:00 pm, Rabb Room, Lincoln Filene Hall

Shirley Sagawa

The American Way to Change: How National Service and Volunteers Are Transforming America

Jossey Bass, 2010

As special assistant to President Clinton for domestic policy, Sagawa drafted the legislation that created AmeriCorps and the Corporation for National and Community Service. After Senate confirmation as the Corporation’s first managing director, she helped lead the development of the new agency and its programs. She is co-founder of the sagawa/jospin consulting firm and Visiting Fellow at the Center for American Progress.

Oct. 15, Noon-2 pm, Crane Room, Paige Hall

Mark R. Warren

Fire in the Heart: How White Activists Embrace Racial Justice

Oxford University Press, 2010

Mark Warren is Associate Professor of Education at Harvard University. A sociologist, he is concerned with the revitalization of American democratic and community life. He is the author of several previous books, including Dry Bones Rattling: Community Building to Revitalize American Democracy.

Co-Sponsored by the Social Justice Initiative

Dec. 10, Noon-2 pm, Crane Room, Paige Hall

Richard Wolin

The Wind from the East: French Intellectuals, the Cultural Revolution, and the Legacy of the 1960s

Princeton, 2010

Richard Wolin is Distinguished Professor of History, Comparative Literature, and Political Science at the City University of New York Graduate Center. His previous books include Heidegger’s Children and The Seduction of Unreason and he writes regularly in Dissent, the Nation, and The New Republic.

Co-sponsored by the Department of Romance Languages and the Center for the Humanities at Tufts (CHaT)

Posted by peterlevine at 9:43 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

September 27, 2010

the heart, the head, and who you vote for

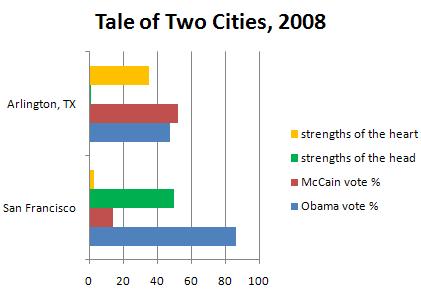

Nansook Park and Christopher Peterson ask people to rank themselves on a battery of strengths that are "intellectual and self-oriented" (such as curiosity, judgment, and appreciation of beauty) and a set of "strengths that are emotional and interpersonal" (such as love, prudence, bravery, and hope). They find substantial differences in the average scores on these scales among U.S. cities. They also find that city-level differences matter for several important outcomes.

An example is the 2008 presidential election. Cities that ranked themselves high on "strengths of the head" chose Barack Obama. Cities that prided themselves on "strengths of the heart" preferred John McCain. I illustrate that pattern with two examples, San Francisco and Arlington, TX. I give San Francisco a score of 50 for strengths of the head because it was top ranked in that category among the nation's 50 largest cities. I give it a 3 for strengths of the heart because, in that category, it surpassed only Seattle and our own warm and friendly city of Boston. Arlington was virtually the mirror image. (Vote counts from here.)

Some caveats would be appropriate. These are self-reported scores, so they may measure the perceived value of the various strengths, rather than their real prevalence in each city. The sample is not random, although the authors argue that it is representative. The relationship between the two virtues and voting outcomes might not be causal; it could be explained by some third factor. (It is not, however, the case that a particular virtue--such as faith--is mainly responsible for the results; the authors check for that.)

Caveats aside, these results seem plausible. America has hard-driving, competitive, creative, and cerebral cities that like Democrats, and warm, friendly, emotional, and devout cities that prefer Republicans. People move to San Francisco, Seattle, and Boston if they think they can succeed in research, consulting, or the arts, and they surround themselves with neighbors who would gag before voting Republican. People move to El Paso, Mesa, and Fresno because they want friendly neighbors and church picnics. They don't necessarily vote Republican (cities in general tilt leftward), but they are far more conservative than their peers in the cerebral cities.

The Republican Party is supposed to be committed to competition and individualism; the Democrats, to solidarity and care. Yet the very cities that are most competitive and individualistic are most enthusiastic about Democrats. Maybe a caring government seems more valuable in San Francisco and Boston than in Arlington, TX.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:18 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

September 24, 2010

reflections after a videoconference

I just finished three consecutive meetings that addressed versions of the same questions: How can universities prepare young people for active democratic citizenship? And how can such efforts be measured and assessed? The first meeting involved Tufts faculty from various departments. I either knew the participants before the discussion began or had network ties with them. We are part of the same organization, with a common work culture. We met in a room where I have spent hundreds of hours. I know exactly where this thoroughly familiar place fits in the broader physical space of Tufts, Medford, Massachusetts, America. We shook hands, helped one another to coffee, and watched each other's faces as we spoke.

Then two young leaders (from the Sustained Dialogue Campus Network) met with me and a colleague in my own office. Now the space was quite small, piled with my own stuff, and extremely familiar to me--although not to my visitors. I understood their backgrounds and the broad outlines of their work lives, but I cannot picture their offices or exactly how they spend their days. The flow of conversation was fluid among the four participants. We talked about potential projects and next steps. We were getting to know one another, which is an important precondition of collaboration.

And then I went to a basement space with a video link, to participate in a virtual conference with colleagues from Tecnológico de Monterrey, a major Mexican university. Now I was in a strange underground room somewhere beneath a physical space that I know well. I was interacting with a face projected on a large, high-quality video screen. I do not know where he sat on the surface of the globe, let alone what he would see if he walked off camera to his right or left. Behind him was a glossy world map, coincidentally showing my real location immediately over his right shoulder, although Mexico itself was obscured. My face appeared in a fuzzy frame below his right hand. He and the several other participants spoke mostly in Spanish, a language which I unfortunately have never studied; but I was able to keep up (to a degree) by pasting their PowerPoint slides into Google Translate on a laptop.

Google's translation revealed remarkably similar themes to the morning's discussion at Tufts. It felt like one conversation, as if you could walk through the screen and find yourself sipping coffee with colleagues in Mexico who would know your friends from Tufts. The video monitor created the illusion of an open portal. Yet thousands of miles, an armed political border, and a language gap separated us. I felt stiffer, more formal, less humorous, and less responsive in the last situation than the first two. It's one world now, but propinquity still matters.

Posted by peterlevine at 4:06 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

September 23, 2010

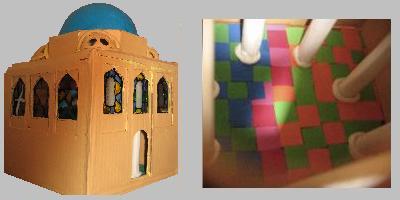

making our own mosque

With all the controversy about building a mosque in Lower Manhattan (not to mention various bills and laws against erecting minarets in Europe), I thought this might be a good time to recycle a photo of the little "mosque" that my daughter and I built when she was seven.

Height: 14 inches. Construction materials: cardboard, plastic freezer baggies, papier-mâché over a popped plastic balloon. Current location: our attic. It is not really a mosque because it lacks a mihrab (to orient people for prayer) or a minbar (the Islamic equivalent of a pulpit). Our motivations in making it were not doctrinal, nor ecumenical, nor political. Rather, this is our amateur homage to one of the world's finest architectural traditions, the heritage of Islamic religious architecture.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:31 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

September 22, 2010

the righteousness that is the special entitlement of homogeneous groups

I am always torn when I hear discussions about the "fragmentation" of American culture or politics, because fragmentation also means diversity and freedom. Yet there are real disadvantages to losing a common dialog. Bill Bishop has written a brilliant book, The Big Sort, about how we have chosen to live in more culturally and politically homogeneous communities than a generation ago. I think he gets the issue just right:

It would be a dull country, of course, if every place were like every other. It's a joy that I can go to the Elks lodge pool in Austin to see the H2Hos, a feminist synchronized swimming troupe accompanied by a punkish band, or that I can visit the Zapalac Arena outside my old hometown of Smithville, Texas, to watch a team calf roping. Those sorts of differences are not only vital for the nation's democratic health, but they are also essential for economic growth. Monocultures die.

What's happened, however, is that ways of life now have a distinct politics and a distinct geography. Feminist synchronized swimmers belong to one political party and live over here, and calf ropers belong to another party and live over there. As people seek out the social settings they prefer--as they choose the group that makes them feel the most comfortable--the nation grows more politically segregated--and the benefit that ought to come with having a variety of opinions is lost to the righteousness that is the special entitlement of homogeneous groups. We all live with the results: balkanized communities whose inhabitants find other Americans to be culturally incomprehensible; a growing intolerance for political differences that has made national consensus impossible; and politics so polarized that Congress is stymied and elections are no longer just contests over policies, but bitter choices between ways of life.

Bill Bishop (whom I know just a little) and his wife sorted themselves into a progressive neighborhood in Austin, where they are comfortable--as I would be. He begins his book with truly troubling quotes from the neighborhood's listserve about how specific conservative neighbors ought to leave the area. It's an important reminder that such "righteousness" is by no means a monopoly of the right.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:49 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

September 21, 2010

the Project Vote survey

Today, Project Vote released a survey of the current opinions of people who voted in 2008. (They randomly sampled from a list of actual voters, which is available from official rolls, so no one in their sample inaccurately reported that he voted.) As I've written before, we ought to understand the views of the majority in the last election, rather than speculating about who will vote next time--especially since such predictions can become self-fulfilling prophesies.

Project Vote finds the following results for 2008 voters:

Approve of President Obama's job performance: 48.1% (all 2008 voters); 91.8% (African Americans); 60.8% (youth); 61.8% (low income); 10.9% (people who identify today with the Tea Party).

First-time voter? 51.5% (youth); 8.5% (all); 0.6% (Tea Partier)

More important to spend money to stimulate the economy or to reduce the budget deficit 44.8% spend v. 48.5% reduce the deficit (all); 55.5% v. 39.6% (youth); 18.8% v. 78.6% (Tea Partiers).

There are 67 items in all, most of them quite interesting. Overall, a picture emerges of the Tea Partiers as outliers in the 2008 electorate. The average voter's opinion will probably move in their direction in November, 2010. But that hasn't happened yet, and the degree to which most voters will agree with them on substantive issues remains very much to be seen.

Posted by peterlevine at 1:13 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

September 20, 2010

the meaning of Michelle Rhee's defeat

Last week, Democratic primary voters dismissed the incumbent mayor of Washington, DC, Adrian Fenty. It looks virtually certain that DC Schools Chancellor Michelle Rhee will also be on her way out. She was the most prominent school district leader in the US, featured on the cover of TIME magazine with a broom as the symbol of her housecleaning efforts.

I have a somewhat unusual take on what happened. Most opinion seems to be divided among these reactions:

1. Rhee was a great reformer. She took over a school system that spends nearly $13,000 per student but only $5,355 on teachers, classroom equipment, and other forms of "instruction." She raised test scores, narrowed achievement gaps, and stopped the flow of students to charter schools, but was defeated by special interests--notably the teachers' union that spent $1 million on the election. The problem, in a sense, was "civic engagement"--the active engagement of people whose interests were threatened by her reforms. No wonder Rhee said (well before the election), "collaboration is overrated."

2. Rhee was misguided or actively malevolent, and DC voters exercised their democratic responsibilities when they stopped her. One commenter on Sam Chaltain's blog decries "her arbitrary mass firings of hundreds of D.C. teachers, including some of their finest, without any reliance on data or due process. ... This isn’t simply the case of another of those misguided, slightly inept reformers who needs another 4 years to carry out her unfinished business before taking a cushy job with the foundations. Rather, Michelle Rhee is a dishonest, megalomaniacal teacher basher--possibly the worst in the country, being egged on by her patrons who see her as the spearhead in their struggle against teacher unions."

3. Rhee and Fenty had basically the right policies, but their job was to persuade DC voters to support them, and they failed to do so. That is Rhee's own reaction. According to Education Week, "The chancellor said one of her mistakes early on was in how she communicated with the public. 'I sort of thought, "Well, OK, if we put our heads down and do the work, after two years we’ll have great results, and everybody would be happy." That was very naive of me,' Ms. Rhee said. 'We weren’t proactive and strategic enough about communication and thinking about how do we get out there and talk about the great things that are happening.'” According to this view, civic engagement is neither good nor bad; it is just a fact of life, and skillful leaders deal with it by effectively communicating.

4. The election had little to do with Michelle Rhee or the schools. It was between Adrian Fenty and Councilman Vincent Gray. Voters did not deliver a verdict on Rhee.

In my view, there was a need for housecleaning in the DC school system. News reports have revealed startling examples of bureaucratic failure: warehouses full of new textbooks that are never distributed to students, payroll systems that cannot keep track of employees.

Rhee presumed that the teacher matters most to a student’s success. Every classroom should be led by a competent and motivated teacher who is supported by efficient systems for distributing textbooks, cutting paychecks, and so on. The most skillful teachers should be deployed in schools where they are needed most, those where test scores are lowest. DC employs excellent teachers--far more skillful and dedicated than I would be--but also many poor ones. Consequently, the Chancellor’s priorities were to remove poor teachers, assign strong ones to troubled schools, and reduce bureaucratic waste.

Research lends her strategy some support: William Sanders and June Rivers deeply influenced national education policy by showing that more effective teachers could move student 50 percentile points higher on standardized tests.

And yet it is far from clear that one can cause better teachers to appear in the classrooms where they are needed most--and persuade them to remain there, year after year--simply through better management. Urban teaching will remain a frustrating job if the social context is difficult (for instance, the crime rate for adolescents in DC is three times the national average), the motivations and expectations of students and parents are misaligned with the goals of the schools, and even high school graduates face poor job prospects. Students will not comply with demanding curricula if they doubt there is a route from the schools to satisfactory employment. Teachers will burn out if the schools prove unable to remedy deep social problems. I have personally known teachers who were reassigned to more difficult DC schools and who immediately left for the suburbs instead.

In any case, imagine that the Chancellor's strategy worked, and she improved the impact of her teachers on students' test scores and graduation rates. If the teachers' impact is limited to the classroom and the school day, it cannot be profound enough to overcome crises in the broader society, from obesity and violence to a lack of jobs. Even if the teachers are able to change parenting styles and other aspects of their students' home environments, we should ask whether this change is desirable. Who are they to change a working-class culture to match the norms and expectations of Georgetown and Cleveland Park? As always, our social problems are entangled with culture and connected to our deep moral commitments, about which we have no consensus.

So I think the people of the District must be civically engaged to make their schools better in ways that they can endorse. More democracy is the cure, and collaboration is essential, not "overrated." But the form that civic engagement takes is crucial. Low-turnout primary elections are poor tools for the people of a large city to shape policy. Teachers unions have a right to participate, but political influence should not be a function of money, and no interest group should have predominant power.

Former Mayor Anthony Williams, with whom I have the honor to serve on the AmericaSpeaks board, introduced innovative ways for citizens of the District to discuss and shape policy. In particular, his Citizens Summits (large, representative, deliberative meetings) generated strategies to "support [the] growth and development of all youth." Summits and other manifestations of deliberative democracy are valuable but not sufficient; there must be daily opportunities for citizens, civic groups, churches, businesses, youth, and others to collaborate with schools on the actual work of education. That is truly an alternative to the strategy pursued by Adrian Fenty and Michelle Rhee, and we need to try it next.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:49 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

September 17, 2010

Justice Ginsburg at the National Conference on Citizenship

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg (following the example of justices O'Connor, Souter, Breyer, and Scalia) is speaking at the National Conference on Citizenship. It's helpful for the Supreme Court--and the judicial branch in general--to endorse civic engagement and civic education. Judge Learned Hand was right: "Liberty lies in the hearts of men and women; when it dies there, no constitution, no law, no court can save it. While it lies there, it needs no constitution, no law, no court to save it."

Justices O'Connor and Souter have made civic engagement a special priority in their retirements--more than speaking, they also organize and lead practical efforts--and Justice Breyer has written substantively about civic education. (Apparently, he addresses it in his new book.)

Today, Justice Ginsburg took a turn to address the topic. She used the "Impeach Earl Warren" campaign as an example of a time when people paid attention to the law and engaged, but in an ignorant way. Asked whether she was disturbed by public "ignorance" (the questioner's term, not hers), she said she was. She cited her own work litigating for equal rights. She said that the litigants who won important court victories for civil rights were ordinary people who understood their rights and the courts.

"The courts are reactive institutions. Why was Sally Reed's case before the Court in 1971? Because there was a women's movement. Why was there activity in the 50s and 60s? Because there was a burgeoning Civil Rights movement. The courts will react ..., not to the weather of the day, but to the climate of the era." I think her point was the importance of active citizenship in the process of reinterpreting and strengthening the law.

Justice Ginsburg argued that case law regarding gender is now quite fair and equitable. In that sense, an Equal Rights Amendment would not change our laws. But our Constitution, she noted, is older than other countries' and does not contain an explicit statement about gender equality that would be found in almost all other constitutions. "My granddaughters will not find that statement," she said, and "for that reason, I remain a partisan of the Equal Rights Amendment."

"If I could design an affirmative action program, it would be for men. It would give men every incentive to be an equal partner in raising the next generation."

Justice Ginsburg praised the Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools, which is now co-chaired by Justice O'Connor, and materials supported by the Annenberg Foundation. "There is an important job to be done to persuade school administrators to request these materials and use them in their classrooms."

Posted by peterlevine at 11:58 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

September 16, 2010

at the National Conference on Citizenship

I am in DC for the National Conference on Citizenship's annual meeting and some related events. It has been a long day and I cannot reflect adequately on all that has happened, but here are some highlights.

In partnership with the Corporation for National and Community Service and the Census, the NCoC is releasing the first annual National Civic Health Assessment. This is the lineal descendant of the Index of National Civic Health (INCH) and the the Civic Health Index, both of which I worked on with many colleagues. But the CHA is based on a national Census survey and is therefore the best data yet.

Today's pre-conference was a series of panels and speeches: very rich and interesting. The Twitter feed (#ncoc) gives a flavor.

Splashlife was publicly launched. That's an impressive new social network the provides incentives for volunteering, organizing, and activism. The young people who built it announced it at NCoC in a creative way. Dressed as waiters and other characters who had infiltrated the audience, they pretended to interrupt a speaker (their colleague) who was giving a PowerPoint presentation about the Millennials. It was all theater and very nicely done.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:18 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

September 15, 2010

philanthropy, the White House and promoting civic engagement

Tomorrow in DC, I'll be on a panel with Sonal Shah from the White House Domestic Policy Council, Chris Gates from Philanthropy for Active Civic Engagement, and Steve Gunderson, President and CEO of the Council on Foundations. The topic is "An Evolving Relationship: How Philanthropy and the Executive Branch Work Together to Promote Civic Engagement." I'm supposed to address that topic for about 10 minutes. I haven't decided what to say but I have a few notes.

In a fine paper on the this subject, Brad Rourke cites Michael Delli Carpini's definition of civic engagement: "Individual and collective actions designed to identify and address issues of public concern." If that is civic engagement, how should the executive branch of the federal government and foundations promote it? I can think of several strategies:

1. They can fund opportunities for citizens to identify and address public concerns collaboratively. Professional public servants do that, and so do employees of many private companies, but somehow their roles aren't addressed under the heading of "civic engagement." Instead, foundations that support citizenship have often funded volunteering or non-career service jobs. Lately, the main source of financial support has shifted. Philanthropy has lost money in the stock market while the Corporation for National and Community Service--the federal program that funds volunteering opportunities--is on course to triple and has an annual budget approaching $1.5 billion.

In a way, the story is straightforward: foundations seeded various programs that are now growing because of federal dollars. But the Corporation is not allowed to spend any funds on electoral activities, even though political action meets the definition of "civic engagement." (As does journalism and media-creation.) Instead, the Corporation has been charged with recruiting large numbers of volunteers to address several big, pre-defined social problems, such as the dropout crisis. That is a different way of thinking about "civic engagement" than we see when citizens define, discuss, and diagnose their own issues. So there is plenty of room for foundations to support participation that is more political or more deliberative, or both, than the Corporation does. Meanwhile, I would like to see the Corporation adopt civic learning objectives for all its participants.

2. They can draw national attention to issues of civic engagement. Citizenship is a contested topic: progressives, conservatives, and others have different opinions about it. But there is also some common ground, and I think our democracy would benefit from paying more attention to active citizenship--even if we continue to disagree about it.

The White House has tried to attract attention to civic engagement on several occasions. George H. W. Bush made it the theme of his inaugural address. President Clinton launched the New Citizenship Initiative in the White House Domestic Policy Council. President George W. Bush held a White House Forum on American History, Civics, and Service (which I attended and blogged about). Those are examples; more could be cited.

It's my sense that today's polarized political atmosphere would make presidential leadership on citizenship especially difficult. When people are willing to call AmeriCorps volunteers "Obama's Brownshirts," it's difficult to have a reasonable discussion of civic engagement. And it's a fact that two thirds of young American voters pulled the lever for Obama in 2008. That means that any concerted effort to get young people civically engaged will tend to draw the center-left, even if that's not the intention.

The Clinton "New Citizenship" effort migrated to civil society when my then boss, Bill Galston, left the Domestic Policy Council and The Pew Charitable Trusts funded his National Commission on Civic Renewal. Although the issue of citizenship needs presidential leadership, it fits more comfortably in the nonprofit sector today and that creates an opening for foundations. The main recent example is the Knight Commission on the Information Needs of a Democracy, a bipartisan effort to address an important aspect of civic engagement.

3. They could reform government so that all Americans had better opportunities to influence and collaborate with public institutions. I think that is the most important goal, but it cuts against technocratic impulses on the left and anti-government assumptions on the right. Arnold Fege has shown that getting communities involved with schools was a major purpose of federal policy during the 1970s, but there is not much of a groundswell for that approach today. DC School Chancellor Michelle Rhee's remark that "collaboration is overrated" is probably closer to the norm.

On his first day in office, President Obama signed an order on transparency, participation, and collaboration. He strongly endorsed the ideal of government collaborating with citizens. Since then, the transparency agenda--giving more people access to more public information--has made much more progress than participation or collaboration. Transparency is somewhat more clear cut than collaboration, and it has an active, organized coalition that is funded by foundations. Collaboration has no lobby, and philanthropy could help build one.

4. They could work to make sure that all young Americans are educated for active citizenship, a cause that will require research, policy reforms, funding, changes in teacher education, and partnerships with institutions other than schools. Civic education has been a low priority for the federal government and a major issue for only a few foundations. There is much more to be done.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:46 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

September 14, 2010

youth interest in the 2010 election

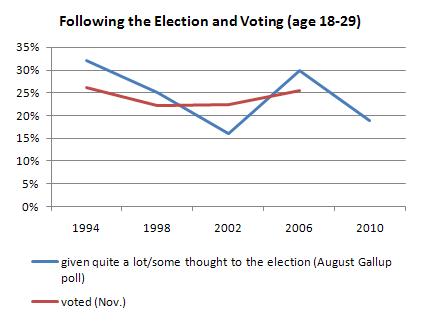

According to a Gallup poll last month, just 19 percent of Americans between the ages of 18 and 29 had paid attention to the election so far. That is a fairly low number in historical perspective, and it suggests that youth turnout may be pretty weak: around 22-23 percent of eligible voters.

My graph shows recent midterm elections. Both trends are much higher in presidential elections. For example, in August 2008, 75 percent of young people were paying attention to the election, and 51.1% ultimately voted.

The correlation between Gallup's "paying attention" surveys and voter turnout in midterm elections is high: 0.84, for you statistics geeks. That makes paying attention a good predictor of turnout. On the other hand, no one has a crystal ball, and the future is ultimately up to us. If you want young people to vote, now would be a good time to get them interested.

Posted by peterlevine at 1:51 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

September 13, 2010

British exceptionalism: how the UK is different from Europe

In Britain, the Industrial Revolution came early, lasted long, and transformed the whole society and much of the landscape. On the Continent, its effects were more limited, and that difference still matters.

In 1950, half the working population in Spain, Greece, Poland, and many other Continental countries was still employed on farms. Even in France, thirty percent worked in agriculture, and almost one quarter of West Germans worked on farms. Agriculture was not heavily mechanized. In the early fifties, there was just one car for every 314,000 Spaniards, and only one of every twelve French households had a car.* I don't know the number of tractors, but one can tell from the rate of car ownership that many roads were unpaved, fuel was scarce, and in general the internal combustion engine was hard to find.

In Britain at that time, only one in 20 workers was employed in agriculture. Despite the Depression, the Second World War, post-War austerity and rationing, and the loss of empire, there were more than 2.2 million cars in Britain in 1950. Two centuries of industrialization had caused the population to migrate and had transformed the very land. Marx and Engels were wrong about much, but they accurately depicted the pace of change in their adopted land. They had the British bourgeoisie in view then they wrote:

- It has accomplished wonders far surpassing Egyptian pyramids, Roman aqueducts, and Gothic cathedrals. ... Constant revolutionising of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones. All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned. ... All old-established national industries have been destroyed or are daily being destroyed. They are dislodged by new industries, whose introduction becomes a life and death question for all civilised nations, by industries that no longer work up indigenous raw material, but raw material drawn from the remotest zones; industries whose products are consumed, not only at home, but in every quarter of the globe.

Put more soberly, the British by 1950 lived and worked in structures designed for Victorian industry in a landscape reconfigured for the rapid movement of goods and people, and they held jobs in commerce, manufacturing, or service industries. Meanwhile, across the Channel, most Europeans lived in villages devoted to subsistence agriculture, whose most important buildings dated to the Middle Ages or the baroque.

Over the next quarter century, the vast majority of those Continental agricultural workers migrated to cities. For example, one million Andalucians moved to the cities of Catalonia, and nine million Italians exchanged regions, mostly migrating northward. Many moved from old farming villages to high-rise apartment blocks: slum-like ones in the suburbs if they were poor, and comfortable ones nearer the central city or the sea if they were more fortunate. They also moved from fields to automated office jobs in one or two generations. All that movement changed the Continent, but less profoundly than the much more protracted Industrial Revolution had affected Britain. For example, outside the banlieus of big French cities, the countryside and the centers of towns are often very well preserved today, notwithstanding two world wars.

Britain's much longer and deeper experience with industrialization by 1950 explains its slower post-war growth rate. The UK had less to gain from industrializing and had to deal with an obsolete stock of factories, machines, and organizations. These differences also explain persistent gaps in culture, expectations, and priorities on either side of the Channel.

*I derive all the statistics in this post from Tony Judt's book Postwar, chapter 10.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:45 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

September 10, 2010

the Coffee Party Convention

The U.S. Constitution is uniquely stable--or rigid--among all the advanced democracies, and we are slower to change our political processes than almost anyone else. Yet we experience occasional periods in which the mass public focuses on political processes and culture (in addition to the standard issues, like the economy and foreign policy). The amendments enacted after the Civil War, reforms passed during the Progressive Era at the local, state, and federal levels, the reinterpretation of the Constitution by Franklin D. Roosevelt and its blessing by the Supreme Court, and the post-Watergate reforms are important examples.

The 2008 election was not about political reform. To an extraordinary extent, the insurgent Democrats seemed satisfied with the rules of the game and promised "change" as a direct consequence of winning the presidential election. Candidate Obama employed a somewhat new style of campaigning within the existing rules, and he endorsed modest ethics reforms and transparency, but those were minor themes in the election.

I don't blame him, because issues like campaign finance reform, districting, and congressional procedures were hardly "ripe." They were not in the public's eye, nor were they major concerns of progressive interest groups. Ideas like strengthening the civic capacities of communities and promoting public deliberations were even further down the national priority list. To raise them to the top would have cost votes, and maybe the election.

By far the most significant change since the campaign was not a reform promoted by the new administration but the Supreme Court's Citizens United decision, which permits corporations to spend unlimited money on campaigns. It should now be obvious to progressives that the political system and culture blocks reform--in ways that are indefensible from most ideological perspectives. We deeply need political reform and innovation.

I will not predict a new wave of reform, as I did in my 2000 book, The New Progressive Era. Today, I am much more attuned to obstacles. But there is at least the potential that large numbers of people will turn their attention to processes and political culture. They might coalesce around the kinds of ideas, leaders, and topics on display at the Coffee Party Convention: Restoring American Democracy.

Posted by peterlevine at 2:06 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

September 9, 2010

moderation, civility, and bipartisanship are not the same, and the differences matter

There seems to be widespread confusion about moderation, civility, and bipartisanship--not just about the words, but about real implications for politics and justice. People who want more radical policies are prone to demand more aggressive rhetoric (example: Paul Krugman); and people who want more civil discourse call for moderate policies (example: David Broder). Attitudes towards parties and partisanship are mixed together with those two questions, when they should all be separated.

Consider the question of how President Obama should have reacted to the recession when he first took office. He could have adopted more or less moderate proposals; the main difference would have been the price tag of the stimulus request, which could have been twice or half as big as it actually was. He could have used more civil or more aggressive discourse in addressing his ideological critics. And he could have constructed both his policy and his strategy for passing it with more or less regard for its impact on the two major parties.

To see that these are separate issues, consider that the president could have doubled the dollar value of the stimulus package but defended it with elaborate courtesy, or he could have halved it and shoved it in the face of conservatives in Congress. He could have tailored it to provide cover for wavering Republican legislators, or deliberately constructed it as a "wedge issue" to embarrass them.

Moderation refers to the content of the policy. It falls between timidity and recklessness. So defined, it is a virtue: close to prudence. However, whether a given policy actually is moderate and prudent is a difficult question. Some would say that the Obama stimulus package and health care reform bills were timid, not moderate. Others think they were breathtakingly radical. Everything depends on what would work best--something we cannot know for sure but can rationally debate. If you think that Keynes was wrong and governments cannot stimulate demand in recessions, then the stimulus package was profligate and immoderate. If you think that the recession demanded twice as much Keynsian stimulus, then the package was timid and weak. It was moderate only if it was the right size.

Civility refers to a style of discourse. Civil speakers refrain from personal attacks, imputations of bad motives on the part of their opponents, and highly negative language. Civil speakers presume the basic good faith of other people until clearly proven wrong, and do not give up on individuals just because they belong to groups that the speaker dislikes. Civility means trying to keep the conversation going and welcoming replies from the other side, rather than trying to exclude opponents.

As such, civility is a virtue--certainly in ordinary life. But it is not a transcendent virtue and it can trade off against other virtues, such as clarity, commitment, and moral passion. In politics, I think it generally pays off. For example, I suspect that President Obama has polled better than one would expect (given the economy) because people basically like his courteous style. But there can be a political cost if civil language obscures important differences or fails to motivate "the base."

Partisanship means lining up with a party and making tactical and strategic choices to benefit your party over the others. It is by no means always wrong. Parties are vehicles for achieving social change. If one of the parties reflects your views much better than the others do, you should support that party. If you hold political office, it may be wise to win control of the government even if that means playing hardball. For example, Republicans may be trying to prevent the administration from successfully addressing the recession; and while that has a cost for America, it is not unprincipled, if one assumes that they would legislate for their own principles once they won Congress back. Partisan competition is good for democracy because it gives voters consequential choices.

On the other hand, professional politicians often neglect the costs--the collateral damage--of pursuing partisan strategies because their self-interest aligns with their party's. Partisan strategies often fail because our system is engineered to require at least some votes from both parties for important legislation. And a partisan lens can obscure the truth if one starts to believe that everyone on either side of the aisle is alike and that the only pathway to reform is for your party to win more seats. I think that is simply a false interpretation of reality in our system of weak parties and entrepreneurial candidates.

For what it's worth, I would tend to favor stronger, bolder policies. I think our actual policies are weak rather than moderate. I welcome a robust debate but I would recommend conducting that debate with basic rules of civility even if one's opponents fail to be civil in return. Civility is popular, it makes uncivil opponents look bad, and it promotes broad public engagement. (When politics turns into a shouting match, most Americans tune it out.) I favor clear partisan differences and electoral competition, but I believe our system rewards partisan maneuvering even when the collateral damage is too high.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:36 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

September 8, 2010

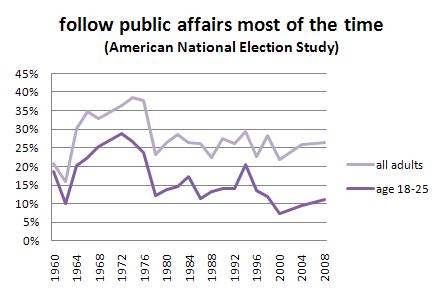

graph of the day: paying attention to public affairs

Here is the trend for the proportion of people who say they pay attention to public affairs. The lower line shows the trend separately for younger adults, ages 18-25.

I notice a few points:

- It seems that "the Sixties" grabbed people's attention--older people's more than young adults'.

- The interest of the whole population has been pretty stable since the 1970s, despite momentous changes in the news media, which morphed from three TV channels and metropolitan daily newspapers to cable, the Internet, and cell phone apps. Even as the supply shifted, demand was steady.

- Younger people have been less engaged in recent years than in the 1970s, 1980s, and early 1990s.

- The past decade saw an upward trend for both age groups, albeit from low baselines.

- Young adults are not too far below their 1960-2008 average (about five points below), but the gap by age was larger from 1998 to 2008 than it was earlier.

All of this matters because people who pay attention have the most impact, and because habits of news consumption that form in early adulthood tend to stick.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:28 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

September 7, 2010

new CIRCLE website

We just launched our new website at www.civicyouth.org. That's the same address we've used since 2001, and it's mostly the same content, but there's a whole new look and organization. I see some items that need to be moved around, missing legends on graphs, etc. But please check it out: it's the best source of research, data, evaluation tools, maps, policy analysis, and other geeky stuff related to young people's civic engagement.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:22 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

September 3, 2010

students as part of the accountability puzzle

Yesterday, I suggested alternatives to holding teachers accountable on the basis of test scores. Just a few hours later (by coincidence), I was shown an interesting initiative from the Boston Public Schools. All Boston high school students will soon begin completing "Constructive Feedback Forms" about their teachers each semester. These very carefully constructed surveys do not ask the students to rate their teachers as good, bad, nice, smart, or by any overall measure. Instead, they ask a whole series of very specific questions about teaching practices. How soon after the bell does the class get down to work? How many students participate in discussions? In what ways does the teacher provide feedback on homework?

The union and school system endorsed the policy, which is pretty modest because only the teacher receives the anonymous results. It would be interesting to consider sharing the results in some form with administrators, mentors, or other colleagues. I see the disadvantages of those ideas, but they are worthy of experiment.

Another fascinating aspect of this policy is its origin. Students on the Boston Student Advisory Council developed it--both the outline and the details--and succeeded in persuading the Boston School Committee to approve it. Those students are supported by Youth on Board (a nationally recognized nonprofit) and by the school system's Office of High School Renewal, so they perform excellent, well-informed, and effective work as.public leaders.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:51 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

September 1, 2010

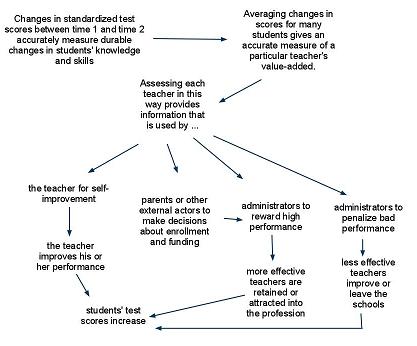

the value-added debate in education policy

The debate about assessing teachers' impact has reached full volume. The Los Angeles Times recently released a public database that rates teachers' "value added," the New York Times has a new front page article about that kind of method, the Economic Policy Institute has published an important paper by 10 famous authors against it (pdf), and various prominent bloggers have weighed in.

We must assess the performance of public employees whom we pay for important public tasks--teachers included. Everyone who has ever been inside a school knows that teachers differ in their skills, relevant knowledge, and motivation. Once upon a time, we trusted educators--teachers, administrators, and unions--to assess themselves, but there is pretty broad dissatisfaction with that approach today.

The leading solution--enshrined in federal and state law--is to use standardized test scores to assess teachers. But now we're supposed to use them in a sophisticated way, not just looking at the average score for each class (which is evidently affected by many factors other than the teacher). The leading sophisticated approach is to assess average changes in a teacher's students over time. In essence, that method controls for students' starting position and relies on the Law of Large Numbers to even out random or external factors that might affect any given kid.

It's not a crazy theory--it has some research support, especially from the groundbreaking work of William Sanders--but notice how many premises and causal relationships the full strategy assumes:

This can go wrong in so many ways. Tests can be poor measures of students' competence: they are never perfect measures. The Law of Large Numbers does not apply in this case, because each teacher can have a significant impact on only a modest number of kids. Hence there are large random fluctuations in value-added scores.

I have never seen evidence that parents try to place their kids in schools with the highest "value-added" teaching staffs. It would be odd if they did, because a student benefits more from a privileged peer group or a good school climate for learning than from teachers who add the most to standardized tests. (Larger increases can be achieved in low-income schools that don't face "ceiling effects," but you don't see affluent parents enrolling their kids in those schools to reward the teachers.)

When teachers use standardized test scores to modify their own performance, they often "teach to the test" and narrow the curriculum. When administrators use such data, they do not consistently enhance the strength of their teaching staffs; they certainly don't make the workplace more desirable for talented teachers. Even if a school's faculty does add more average value to test scores, that doesn't mean that graduates will become better citizens--or even that students will stay in school.

Kevin Drum thinks we face a Hobson's Choice: no tests and no accountability, or poor accountability through testing. "The criticisms of value-added seem compelling. At the same time, if a teacher scores poorly (or well) year after year, surely that tells us something? At some point, we either have to use this data or else give up on standardized testing completely."

I'm not saying that the answer is easy, but there are alternatives to this dilemma. We could reorganize schools so that teachers were able to hold one another more accountable: what I have called "internal accountability." (Evidence from other fields shows that when internal accountability system are replaced with external measures, people become less motivated to do good work.) We could also bring parents into schools as partners, not just consumers, and boost what I have called "relational accountability."

Either way, we would shift the metaphor. Teachers wouldn't be service-providers whose service must be measured in a standardized way. They would be members of a community (also comprised of families), who hold one another accountable for contributions to a common task.

These ideas may sound idealistic, but they actually make fewer assumptions and leaps of faith than the supposedly hard-nosed strategy shown in the diagram above--which is embodied in current law.

Posted by peterlevine at 2:15 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

Jonathan Lethem, A Fortress of Solitude

I recently read The Fortress of Solitude, a 2003 novel by Jonathan Lethem (having previously read Motherless Brooklyn, a funnier and perhaps tighter book by the same author). Fortress of Solitude has been compared to Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: both are heavily fictionalized memoirs that begin in early childhood, when language and memory are still unformed, but emotions are raw and potent. Both focus on a sexualized and delinquent adolescence, deal with questions of national or racial identity, explicitly consider art and aesthetic theory, and end with the protagonist as an author reflecting on his own story.

Joyce's character lives in British-ruled Dublin late in the 1800s, whereas Lethem's hero grows up as one of two white boys in an otherwise African American block and school in the Brooklyn of the 1970s. The local bullies, the protagonist's best friend, and his main girlfriend are all Black, while in Portrait of the Artist the key figures are Irishmen. Joyce's hero debates Shakespeare, whereas Lethem's writes about soul and Motown.

I found some personal resonances. I'm just a couple of years younger than Lethem and his fictional protagonist. My aunt and uncle actually lived not far from his fictional setting. My father, a cousin, and several other people I've known attended the high school where the hero studies. My college was not much different from his. Black-White relations, graffiti, punk, and the condition of bankrupt New York City were peripheral or contextual issues for me, central in the plot of Fortress of Solitude.

It's an ambitious or even risky book. The biggest risk is departing from a fully naturalistic plot: let's just say that some things happen in the novel that could not happen in the real world. I felt it become somewhat slack in the middle, once the hero leaves Brooklyn, but become suddenly taut again at the end when all the plots collide. Like the plot, the prose is ambitious and risky. Consider, for instance, this early paragraph with its evocation of filtered childhood memories, its free indirect discourse (where do Isabel's thoughts begin?), and the use of "ribbon" as a verb:

- The boy lingered in the study and paged through Isabel's photo albums while the mother sat on the back terrace, smoking. Isabel watched a squirrel ribbon the telephone pole, begin to scurry across the fence top. The squirrel moved as an oscillating sequence of humps, tail and spine bunching in counterpoint. Some humped things are elegant, Isabel mused, thinking of her own shape.

I think Lethem pulls off a fine novel, although sometimes it's a close-run thing.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:10 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack