« July 2010 | Main | September 2010 »

August 31, 2010

what happened to the new Obama voters?

Project Vote is pushing an important line of argument. They say that our policy debate is distorted because the media is fascinated with the Tea Partiers ("Who are they? What do they want? Will they affect elections?") and is ignoring the huge number of new voters who turned out in 2008. Those new voters tended to be younger, less wealthy, more racially diverse, and more politically progressive than the typical US electorate, and they won a national election. If the press today would constantly ask, "Who are they and what do they want?" the whole policy debate might be quite different.

Lorraine C. Minnite writes, "heading into the 2010 congressional midterm elections the views of traditionally under-represented groups who were mobilized in record proportions in 2008 have been drowned in tea." See her "What Happened to Hope and Change? How Fascination with the 'Tea Party' Obscures the Significance of the 2008 Electorate" (PDF) and a soon-to-be released Project Vote survey.

Reporters focus relentlessly on predicting the next national election. (I've quoted the former CNN political director, Tom Hannon, saying, "the most basic question about [an] election ... is who's going to win.") From that perspective, it's somewhat rational to focus on the Tea Partiers and not the recent Obama voters. Current polls that screen for likelihood of voting in 2010 suggest that the electorate will shift rightward again in 2010 because of who turns out. Thus, if you want to predict the next election, it makes sense to focus on the new conservative voters. Two important caveats, however, will probably be missed. First, the Tea Party will not represent the median voter, who will be moderate; and second, the electorate will probably swing back leftward in 2012.

Assuming that the media (and the blogosphere) continue to focus on predicting the 2010 election, the only way to shift the discussion is for progressive constituencies to threaten to vote. They need to tell pollsters that they are excited to vote, and they need to take public steps--like marches and protests--that indicate mobilization. That's how the game is played right now, and they're not playing well.

But the game isn't satisfactory. "The most basic question" about politics is not "who's going to win." The most basic question is: What should we do? Although the press can't answer that for us, they could provide information relevant to our decisions.

From that perspective, "Who will win the next election?" shouldn't matter much. At most, it should have a modest impact on our strategic plans, but it should not cause us to change our own goals. (Thus the relentless focus on the horse race is problematic.) Who voted in the last election is perhaps a bit more relevant, because the winners presumably have some democratic legitimacy as the current governing coalition. Who might vote if we changed our politics is more interesting, because it invites us to consider a wider range of strategies. I'll be looking forward to the Project Vote survey for that final reason--it will suggest ideas about how we might be able to mobilize new progressive voters with new progressive policies.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:20 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 30, 2010

Where Harvard Meets the Homeless

Scott Seider has published a new book entitled Shelter: Where Harvard Meets the Homeless. It's about a homeless shelter that is entirely managed and staffed by Harvard students.

Most of our work at CIRCLE concerns the civic engagement of people far different from those young leaders. We focus on the half of the population that does not attend college at all, let alone highly selective, private, four-year universities. But Seider's topic is an important one because the kinds of people who gravitate to ambitious civic or political organizations at institutions like Harvard will soon run strategically important parts of our civil society and politics.

This generation is certainly different than their predecessors who would have flocked to Students for a Democratic Society and tried to block Robert McNamara from leaving campus. Today's Ivy League undergraduates are more entrepreneurial, probably better organized, possibly more thoughtful, but lacking a comprehensive theory of how to change society.

As I wrote in my blurb, "Scott Seider's rich and insightful study of Harvard students who run a homeless shelter provides an informative portrait of today's young leaders and their struggle to understand and confront injustice."

Posted by peterlevine at 12:29 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 23, 2010

on vacation until August 30

And I'm trying to stay offline until then. We are on Martha's Vineyard, about which I posted last year.

Posted by peterlevine at 4:21 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 20, 2010

what is corruption?

I'm about to write a chapter that hinges on the thesis that American politics is corrupt. Most Americans would agree, although their reasons and solutions vary (and, as shown by Transparency International's map, people feel worse about corruption in most other parts of the world). But what does "corruption" mean?

It cannot mean that the political system generates results you abhor, because that's the nature of politics (collective-decision making) on a large scale. Other people are going to choose to do things that you consider wasteful, murderous, immoral, treasonous. That doesn't mean the system is corrupt.

It cannot mean that the political system favors the wealthy. I am an economic populist, but I agree with Charles Lindblom's theory of the "privileged position of business." Prosperity is a popular public good. In order to promote prosperity, we have to make discretionary investors happy. Discretionary investors are rich. So governments try to make rich people and governments happy. That by itself is not corrupt.

It cannot mean that political institutions do not live up to their express or original principles, because sometimes those principles are abhorrent and we welcome their abrogation. And sometimes institutions try to honor good principles but simply fail.

It cannot mean that leaders act on bad motives. Yes, there are good and bad motives, and we can recognize them in others--or else the whole idea of proving intent in a law court is a farce. But the intent of political leaders is a problematic issue. It's hard to discern their true motives because we observe them at a distance, mediated by various untrustworthy sources. Besides, politicians can do great things for selfish motives (such as their own re-election) and horrible things with good motives.

It cannot mean simply the exchange of official decisions for illegal payments, because people have used the concept of corruption more broadly for at least 25 centuries. Bribes are corrupt because they are examples of something more general.

So I don't think corruption is any of these things at once, but it might be some combination of them. Unfortunately, a combination is what we observe every day.

Posted by peterlevine at 4:05 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 19, 2010

the best colleges for service-learning

US News & World Report has a list of the 30 best colleges for service learning. (It explains that "volunteering in the community is an instructional strategy [in which] service relates to what happens in class and vice versa.") US News also provides lists of seven other approaches to enriching the traditional academic format of college, from "undergraduate research projects" to "study abroad."

I am glad that service-learning is treated as a technique that is "believed to lead to student success." It does help at least some students academically when it's well implemented. I am also pleased that both my current and previous universities--Tufts and University of Maryland--make the top-30 list. These choices were made by an expert panel who reviewed formal nominations. They do not have the final word or ultimate wisdom; their list may be biased in various ways. But if you take it as a valid list, it supports a few generalizations about the field:

- Fully one third of the "winners" are small, private, liberal arts colleges, even though only a tiny proportion of American students attend such universities.

- The big state universities are not very well represented, notwithstanding their historic mission. There are just seven such campuses on the list: IUPUI, Maryland, Michigan, Michigan State, North Carolina, Portland State, and Wisconsin. That's either because of an unintentional bias in the selection process or because the big state schools aren't focused on community engagement.

- Among trend-setting, highly competitive Research I universities, the leaders in service-learning seem to include Brown, Duke, Michigan, Stanford, Tufts (if I may say so), Tulane, University of Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

- If I had a vote, I'd recuse myself on Tufts and Maryland but would strongly consider voting for Bates, IUPUI, Portland State, University of Pennsylvania (all selected by the US News panel), plus Pitzer, Georgetown, Minnesota, and Providence College, among others.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:29 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 18, 2010

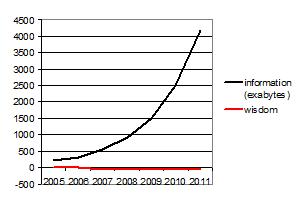

where is the wisdom we have lost in information?

(Aspen, CO) Thanks to a reference by Richard Adler, I see that all the words ever spoken by human beings took 5 exabytes of data. In 2010 alone, we will produce about 750 exabytes. In 2011, we will produce about 1,750 exabytes, and rapidly rising. So in one year, we will communicate 350 times more data than we have spoken in the past hundreds of thousands of years.

But the rate of growth in aggregate wisdom seems modest, at best. I'd sum it up like this:

I thought it was Winston Churchill who said, "The population of the earth rises exponentially, but the sum total of human intelligence is finite constant." I can't find that quote online, so maybe I garbled it. But if you substitute "exabytes of data" for "population," it seems about right.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:26 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 16, 2010

the unbundling of everything

(Aspen, CO) There has been much talk at the FOCAS conference about the "un-bundling" of news products. You used to get one newspaper that "bundled" together international and local news, serious issues and fluff, editorials, letters, comics, sports scores, want ads and classifieds. Now those products can be obtained separately, and most people are not choosing to purchase any serious journalism.

It strikes me that much more than the newspaper has been unbundled over the last century. We've unbundled political parties into collections of entrepreneurial politicians and discrete ballot initiatives. We've unbundled careers by losing most of the unionized jobs and secure, lifelong positions. We've unbundled religion by creating a proliferation of "faith-based" networks, organizations, and self-help groups that are separate from congregations. We've unbundled civil society by moving from demanding membership organizations to a la carte networks. And we've unbundled families.

The result is a lot more freedom. But people will use that freedom to choose not to discuss and address public problems, unless they have skill and motivation for civic engagement. Skill and civic motivation are scarce and very unequally distributed. The cognitive demands of citizenship have risen: you need to know a lot more to navigate the complexities of modern, unbundled institutions. Meanwhile the motivational hurdles have risen, because no one can make you engage with public issues or obtain the skills and knowledge you would need to do so effectively. Public education can help by getting youth on the right track, but the effects of even the most engaging and inspiring educational experiences are likely to fade in later years. As a result, too few people are engaged in addressing our public and community problems, and the public discourse is dominated by those who remain highly motivated--strong ideologues and wealthy interest groups.

Posted by peterlevine at 6:58 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 15, 2010

forum on communications and society

(Aspen, CO) I am here for a conference called FOCAS: Forum on Communications and Society. The topic is how to implement the recommendations of the Knight Commission on the Information Needs of Communities. The Knight Foundation was originally endowed by newspaper magnates and retains a concern with professional journalism, which is now in dire condition. (At least one quarter of America's paid journalists have been laid off already in the past decade.) But the Commission wisely decided to focus on the fundamental "information needs" of communities instead of the state of the news media and journalistic profession. And it adopted a hopeful tone, optimistic about fundamental innovations.

Present at FOCAS are some interesting folks. To name just a few: Julius Genachowski is chairman of the FCC; Marcus Brauchli is executive editor of The Washington Post; Alberto Ibarguen is president of the Knight Foundation; and Craig Newmark started craigslist. The heads of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, National Public Radio, and the Public Broadcasting Corporation are all on the agenda, along with executives from News Corporation, Microsoft, E.W. Scripps Company, and NIKE, among other companies. I will be listening for ideas about how to make public broadcasting more effective, replace the traditional functions of the metropolitan daily newspaper, and help disadvantaged Americans use and create knowledge.

The meeting will stream online, with a chat function, here.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:27 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 13, 2010

you know you're in Germany because the roofs are all covered with solar panels

Last week, driving around Alpine Europe, we crossed the borders of Germany, Austria, Liechtenstein, Switzerland, and Italy, sometimes more than once. Nowadays, the border guards are gone, and even the roadside signs marking borders are very modest, but you can tell you're in Germany by one simple clue: everything is covered by solar panels. There are fields of photovoltaic cells, like crops, and they cover every other roof. That's not just my impression, but a significant national phenomenon, driven (natürlich!) by policy:

Data come from here. Interesting explanatory report here. (Liechtenstein, with just 35,000 people, doesn't count.)

Posted by peterlevine at 4:36 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 12, 2010

what is the best participatory process in the world?

The Bertelsmann Foundation--the largest foundation in Europe, I believe--will give its Reinhard Mohn Prize in 2011 to the best project anywhere in the world that "vitalizes democracy through participation." I am serving on an advisory board for the prize, but a major aspect of the competition this year is open and public. You can go to this website and nominate a project or read and vote on the nominees (or both).

I personally nominated the Unified New Orleans Plan, which was written after Hurricane Katrina by thousands of citizens whom AmericaSpeaks convened for town meetings; Community Conversations in Bridgeport, CT; and deliberative governance in Hampton, Va. These are strongly institutionalized, politically significant examples of public deliberation in the US. They have recruited diverse and representative citizens in large numbers, addressed real problems, and strengthened their communities' civic cultures.

There are 78 other nominees right now. They include clever ideas, like an online space for citizens of different EU countries to agree to vote together. Promising work comes from unexpected places, like a deliberative polling exercise at the municipal level in China. There are many e-democracy platforms, most of which seem to be suites of online tools for following the government and discussing issues. The Danish Board of Technology, which has an impressive track record of public engagement over many years, convened people in 38 nations to discuss global warming together--an impressive experiment that yielded news reports in many of the countries.

Participatory Budgeting (which gives citizens the right to allocate public funds in deliberative meetings) has spread from its homeland of Brazil to places like Tower Hamlets, London and the Indian state of Kerala. Some important legislative reforms have been nominated and should be celebrated, although I am not sure they meet the criteria of the prize. The Central Information Commission in India is an example.

I am not sure that my own nominees are the best, but I am most enthusiastic about all the examples that are multidimensional, lasting efforts, driven by several institutions instead of only the government, and involving work, cultural production, and education as well as dialogue and advice. Some examples other than my own nominees would include Co-Governance in Belo Horizonte, Brazil, perhaps the Abuja Town Hall Meetings in Nigeria (if they are genuine democratic spaces), and Toronto Community Housing’s Tenant Participation System.

Vote for your favorites!

Posted by peterlevine at 3:52 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 11, 2010

a bull market in youth civic engagement

Today I received my copy of the Handbook of Research on Civic Engagement in Youth, edited by the star team of Lonnie R. Sherrod, Judith Torney-Purta, and Constance A. Flanagan. It provides 706 large pages--24 chapters by 53 authors--about how, why, and when young people participate in politics and civic life.

Today I received my copy of the Handbook of Research on Civic Engagement in Youth, edited by the star team of Lonnie R. Sherrod, Judith Torney-Purta, and Constance A. Flanagan. It provides 706 large pages--24 chapters by 53 authors--about how, why, and when young people participate in politics and civic life.

In 1985, Timothy Cook wrote an American Political Science Review piece entitled "The Bear Market in Political Socialization." As he noted, the body of research on how people become citizens was then strikingly small, considering that the future of our democracy depends on that question. A few fine scholars wrote on this topic, but they were scattered among political science, developmental psychology, and education research, with little interdisciplinary dialogue and few inroads into other relevant disciplines, such as sociology and communications.

Further, the current scholarship had virtually no impact on practice. Educational policies, classroom strategies at all levels (from kindergarten to graduate school), community service programs, and the efforts of political campaigns and the news media to reach young audiences were some of the areas of practice that were conspicuously uninfluenced by theory or research about young people as citizens.

The new Handbook illustrates that we are now in a bull market, with scores of active scholars turning out heaps of research on youth civic engagement and interacting constantly with practitioners.

My own chapter, by the way--co-written with Ann Higgins-D'Alessandro--considers some of the crucial philosophical questions that arise when we ask how young people should be educated for citizenship. A not-so-hidden agenda is to persuade readers that education is not a matter for positivist social science alone. It is intrinsically about values; and good research is defined in part by having good values.

Posted by peterlevine at 3:35 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 10, 2010

states versus markets (a somewhat different take)

On a major blog some months ago (unfortunately, I can't find the link), the blogger complained about his Internet-service provider, and a debate ensued in the comments section about whether corporations or governments are worse. One writer remarked, in effect: Companies can be as bad as government agencies, but when a company mistreats you, you can just walk away. It's irrational to get all worked up about that. When the government wastes your money or time or gives you bad service, it's an outrage. The author concluded that markets are better than governments.

I have a somewhat more complicated view. I think it is smart to minimize your emotional reaction when a company performs poorly; just take your business elsewhere, if you can. It is more appropriate to be angry at government because:

- It usually offers less choice or none at all, which is frustrating.

- We have a legitimate sense of ownership and identity with our government. It is "ours." Its bad performance is a matter of deeper significance for us.

- The mechanism of reform in government is "voice," not "exit."* Government services improve when some citizens (perhaps including state employees) take it upon themselves to complain and advocate for change. That can also happen in a marketplace, but the main mechanism for improvement in a market is Darwinian. Customers are supposed to move their money to the best-performing companies and not provide free advice. So we should hope for frictionless, unemotional decisions in a market and periodic expressions of anger in the public sector.

The question is whether, when, and for what purposes we want to rely on voice versus exit as the mechanism of improvement. I see the advantages of exit and competition and am therefore biased in favor of markets as the means for delivering ordinary services. But there can be at least three powerful rationales for state involvement:

- To promote equity. Markets don't deliver services to everyone. For example, there is virtual consensus in the US that governments should fund universal k-12 education, a view shared even by market-enthusiasts who believe that education should be delivered by private schools. Unless the government funds education, being born poor will be a life sentence to poverty. That means that we hold the state accountable for education even if it chooses to outsource the work of educating. Voice is inescapable.

- To promote security. Governments are in the security business when they guard our borders, arrest criminals, prevent pollution, regulate markets, or provide fundamental services to people in need. We can debate which forms of security are appropriate and whether the government should directly provide them or else fund private entities to do so. But again, when we believe in some form of society-wide security, we hold the government accountable for results and use voice to express dissatisfaction.

- When we feel a sense of ownership in an object. For example, Americans think of the national parks as theirs. If they don't like the services at Yellowstone, they are not going to be happy switching over to some private resort. It doesn't matter whether the National Park Service does the work at Yellowstone or outsources it; as long as people feel they own the park, they will hold the federal government accountable for it. This feeling is socially constructed, not inevitable. We could feel ownership over different acres instead of Yellowstone--or none at all. But the initial creation of the National Parks was popular and has been validated by decades of public opinion.

To complicate matters, all markets are (at best) imperfectly competitive, and there can be choice and competition among governments (because individuals and companies can move). Thus voice is sometimes appropriate in the private sector; and exit sometimes matters in the public sector. Also, communities as well as governments can own public resources. Finally, some private corporations own resources that people identify as theirs--for instance, fans identify with their local professional sports teams. In such cases, whether to honor voice is the company's choice, but it is often a wise one.

* Albert O. Hirschman, Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States (Harvard, 1970)

Posted by peterlevine at 9:21 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 9, 2010

talking about this generation

I am paid to write about the civic and political engagement of young Americans. Many people who are interested in this topic believe that today's younger adults, often called the Millennials (born 1985-2004), have distinctive and admirable attributes that will help to remedy the deep problems that we older people have created for them. Chief among their distinctive characteristics are a propensity to serve (marked by record-high volunteering levels), appreciation of diversity, creativity and entrepreneurship, and resistance to the dead-end ideological debates and culture wars of the previous decades.

The portrait is controversial and subject to much debate. For example, I keep on my shelf the following pair of books. Generation We by Eric Greenberg and Karl Weber is subtitled, How American Youth are Taking Over America and Changing Our World Forever. Norman Lear provides one of many enthusiastic endorsements on the back cover: "The Bible tells us, 'a little child shall lead them.' … Greenberg and Weber chronicle today's wonderful young people as they push, pull, and propel us toward global salvation." But I also own The Dumbest Generation by Mark Bauerlein, subtitled How the Digital Age Stupefies Young Americans and Jeopardizes Our Future, or Don't Trust Anyone Under 30. The back cover warns: "If they don't change, they will be remembered as fortunate ones who were unworthy of the privileges they inherited. They may even be the generation that lost that great American heritage, forever."

If these books are witnesses for the defense and the prosecution, I would give my ultimate vote to the defense. I think the positive trends (rising volunteering rates, strong turnout in 2004 and 2008, and tolerant attitudes) outweigh the negative ones (record-low interpersonal trust and news media use)--while other measures of civic engagement (such as students' knowledge of politics) are remarkably flat. Although there is nothing inevitably good about youth movements--European fascism was an important example--this generation inspires somewhat more hope than fear in me.

On the other hand, the whole business of making a case for or against a generation should be viewed with suspicion, for four reasons. First, generations are arbitrary constructs: babies are born every second, and all the important trends in civic engagement are smoothly continuous, not broken suddenly at twenty-year intervals. Second, there are many aspects of civic engagement, and some rise while others fall. Third, people born around the same time can have totally different formative experiences. For example, about one third of young Americans are not graduating from high school today, and they come of age in very different circumstances from their contemporaries who attend four-year colleges. The gaps in volunteering and voting rates by educational experience are vastly larger than any differences among generations. (Almost three quarters of young college graduates voted in 2008, compared to 26% of young high school dropouts.)

Finally, we do not know how the current generation of younger adults will turn out over their life course. The children of post-War suburbs who bought Davey Crocket hats and acted like Charlie Brown and Lucy were wearing dashikis and love beads a decade later. Today's generation had early experiences with peace and prosperity, but more recently have faced the longest war in American history and the deepest recession since the Great Depression. To the extent that they have typical formative experiences, we cannot yet say what those experiences will be.

Notwithstanding all those caveats, there is something to the idea of social reform through generational mobilization. In the 1920s, Karl Mannheim argued that younger adults have valuable roles as critics, reformers, and renewers of society, even as elders contribute experience, and people in their middle years hold most of the managerial responsibility. Furthermore, when one is born affects one's development as a citizen, even though other factors also matter. It is important that today's youth grew up with Facebook and two wars in the Middle East, instead of Walter Cronkite and war in South East Asia.

Thus one does not need a strongly positive evaluation of the Millennials to motivate a commitment to youth civic engagement. It is always valuable to get younger adults constructively involved, and to do so effectively requires careful attention to their particular traits. Each cohort has distinctive assets and challenges which one must understand to develop strategies for civic renewal. With regard to the current generation of young adults, the most salient characteristics appear to be a fondness for online social networking, experience with volunteer service, comfort with diversity, unprecedentedly high levels of support for the winning presidential candidate (in 2008), low interpersonal trust, and low levels of formal group membership. This is the mixture of which something valuable can and must be made.

Posted by peterlevine at 4:57 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 6, 2010

in praise of Glurns

We are back from an Alpine driving vacation. I don't post travelogues on my blog, but I will mention a highlight to give a flavor of our trip. The little Italian town of Glurns is missing from many guidebooks but is amazingly appealing. Part of Austria until 1919, it is still German-speaking. It is at 900 meters and surrounded by much higher mountains. Six miles away is Switzerland, and over the border is a valley where the main language is Romansch.

Each of the three roads into Glurns passes through a gothic gate bearing the two-headed Hapsburg eagle. The city wall is mostly complete, and outside rushes a steep mountain stream.

In the middle of town, there's a picture-perfect square with a fountain. The plan (with a forum at the center and radiating streets) presumably dates to Roman times, when Colurnus was a stop on the Roman road across the Alps.

The Laubengasse or Via dei Portici is completely lined with low porticoes on both sides, so that it's possible to walk its whole length without facing the elements. Most of the buildings probably have long and complex histories of construction and reconstruction, but the dominant period for visible facades is the 16th century. The church towers bear onion domes.

Today's population is less than 1,000. For backpackers, skiers, and climbers, there are magnificent Italian and Swiss national parks to the south: Alpine wilderness areas. For history buffs, there's the UNESCO World Heritage site of the Convent of St. John in Müstair, Switzerland, just hiking distance away. We found the Convent itself to be rather modest, but it has been a continuous religious community for 1,230 years and it houses remarkable murals painted around 800--extraordinarily early examples of Christian art in what must have been wild country when Charlemagne passed through on his way to be crowned Holy Roman Emperor in Rome.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:39 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack