« April 2010 | Main | June 2010 »

May 28, 2010

debating civic environmentalism

Yesterday, I helped to lead a kind of seminar for Tufts faculty at TELI, the Tufts Environmental Literacy Institute. We assigned chapter 9 of Mark Sagoff's Price, Principle, and the Environment, which is entitled "The View from Quincy Library or Civic Engagement in Environmental Problem Solving." Mark Sagoff tells a great story about a group of citizens--environmentalists, loggers, and others--in a small California forest town who met in the library because people are not allowed to shout there, worked out a management plan for the surrounding National Forest, got it passed as an act of Congress, and were criticized by the national environmental groups (see a collection of documents, here). The legislation was never implemented because of litigation.

We divided the Tufts faculty into two groups to debate--literally--the pros and cons of civic environmentalism as represented by Quincy Library. The debate focused mostly on scale, and whether it is better to set policy at the local or national level. Expertise also came up, because experts tend to work at the national level and laypeople dominate at the local level. Each side cited this difference in its own favor.

I see some other important issues in the Quincy Library Case. Above all, the national policy debate involves corporations and nonprofit groups, each of which has a fiduciary obligation to seek certain kinds of outcomes. Because they have opposing goals, they are drawn to litigation or constant lobbying over legislative amendments. They are better off with unresolved issues than with compromises, because they can keep on fighting as long as there is no resolution. And they use science strategically, commissioning and highlighting scientific findings that benefit their cause.

In contrast, people came together in Quincy Library as citizens with a problem--the forest was liable to go up in flames any day. Although they differed in values and interests, their differences did not define them. After all, they had overlapping as well as contrasting interests. Thus they had incentives to deliberate, i.e., to discuss values and goals, including aesthetic and moral ones as well as the purely means/ends reasoning that science can handle. They reached consensus. That was not inevitable, but they had a motive to try, which is not the case in the national debate.

I could take the critical side in the debate. I would note that the Quincy Library plan was only acceptable because national environmental laws had stymied loggers and forced them to the negotiating table. I might assert the right of American citizens who live elsewhere to influence their National Forest in California. And I might observe that certain issues--such as climate change--are of overwhelming importance and need to be settled by adversarial politics, command-and-control regulation, and science. Yet I think we are unlikely to see good policies at the national and international level until people can do their own civic work to defend the local environment, as they tried to do in Quincy.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:11 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 27, 2010

where is the public on climate change?

Our views of our fellow citizens tend to oscillate. If we're upset about something, we pessimistically assume that most people are stuck on the other side, or else we optimistically want to change their opinions with skillful "communications" and new "messages." We quickly shift from hope to despair depending on the latest polls or election results.

The reality is surely more complex. People differ a great deal in how much they know and care about any given issue. And most people go through a slow but significant process of learning whenever a new issue arises on the agenda. Their average opinions shift in response to evidence and argument--but not overnight. For instance, if they believe false critiques of the recent health care act, they will not change their minds because of one news program or advertisement. But they will learn the truth over time.

The Public Agenda Foundation has been watching this process develop on the topic of energy and has developed a theory called the public's "Energy Learning Curve.™". Public Agenda finds that people currently favor the easy policies (like tax benefits for individuals who conserve energy, supported by 81%), but they oppose more painful and effective policies (like gas taxes to fund renewable energy: 52% against). That's the current snapshot, but Public Agenda notes, "there are reasons to wonder how well this consensus would stand up under pressure. Our research shows the public does not know critical facts about the problem." For instance, "52 percent thought that by reducing smog, the United States has come 'a long way' in addressing global warming."

Looking more closely, Public Agenda finds the public divided into four groups, "the Anxious (40 percent), the Greens (24 percent), the Disengaged (19 percent) and the Climate Change Doubters (17 percent)." So what we have is not a public opinion on energy and climate change. There are many opinions, some grounded in fact and some in prejudice, some passionately held and some that are off-the-cuff responses to the pollster. These opinions will change; in which direction remains to be seen.

Posted by peterlevine at 5:01 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 26, 2010

naive and sentimental art

These are two works of European Gothic architecture that epitomize the charm of the middle ages.

Bonafatius Bridge, Bruges

Chimères on the roof of Notre Dame de Paris

The Chimères were made and placed on Notre Dame in the 1800s. The Bonafatius Bridge was designed and erected in 1905. There are, of course, thousands of other examples of Romanesque and Gothic art and architecture from all over the world that were built between 1820 and 1950. Big Ben, Yale University, the National Cathedral in Washington, and the Cinderella Castle in Walt Disney World are famous examples. But most people presumably realize that an American cathedral was not actually built in the middle ages. The examples shown above are notable because they can easily fool viewers; one could almost call them "counterfeit Gothic."

I used to regard authenticity as a high value, and I would dismiss a Victorian Gothic structure while admiring even a rather crude work genuinely made before 1200. If that preference is defensible, I think the underlying principle is some version of Schiller's idea of naive and sentimental art. Naive artists do what they think is right or best. They don't see themselves as having a "style" but as making objects that are beautiful and true. In contrast, sentimental artists imitate the styles of other times, admiring their authenticity. After sentimental art arises, naive art becomes impossible.

Thus nineteenth-century European and American architecture is almost all "revivalist" (neogothic, neoclassical, neo-Egyptian, etc.), with the exception of structures that were perceived as functional, such as railway stations and bridges. We see those functional buildings as naive but impressive; we recognize that the Gare du Nord has a style even though its builders just thought they were covering railway tracks. As for the neogothic works, we reject them as sentimental fakes--especially when they infiltrate genuinely medieval places like Bruges or Notre Dame. They may be OK in Orlando, but not in Paris.

But that judgment is contestable. Schiller's distinction between naive and sentimental art is itself a product of a certain time. Placing a high value on authenticity (as he did) is characteristic of Romanticism. One could instead see Victorian Gothic art as very fine, at its best. One could celebrate the spirit of play that sometimes animates it. And one could recognize an authentic impulse in the devout attempt to replicate a defunct culture.

I write all this now because I am reflecting on my visit to the Palácio Nacional da Pena, near Sintra, Portugal, which appears Moorish/Gothic but was really built in 1842-1854. Crowning a steep mountain, it overlooks a real Moorish castle that was itself heavily reconstructed in the same period (deliberately to look like a Romantic ruin).

Pena is fun. Because it was meant for play, everything is designed for maximum entertainment, not for any serious purpose. For instance, there are fortifications meant simply to be walked on for the view; they have no defensive purposes. Inside, concrete walls are painted to look like wood. Even the trees on the mountain's slopes were carefully planted by a monarch of German extraction, to resemble a Teutonic forest.

This kind of example exposes the decadent currents in revivalism, the real pitfalls of inauthenticity. Play is fine; we are homo ludens. Gothic woodcarvers engaged in play when they depicted magical beasts on misericords. But when you tax people to build expensive seats of government, you had better be at least somewhat serious. Pena is furnished in a cluttered, Edwardian style, just as the last royal family of Portugal left it when they fled republican rebels. They deserved to be kicked out of a place so frivolous and so costly. I thought the parts of Pena that remain from a medieval monastery (namely, a small chapel and a cloister) were far more satisfying that the pseudo-Gothic additions, not because the craftsmanship was better in the former, but because excellence requires a degree of seriousness.

My bottom line: fine art needs an authentic motivation, but imitating another culture can be done with authenticity.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:58 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 25, 2010

young voters in Kentucky

Two belated notes about the Kentucky Senate primary from someone who studies youth voting. First, Rand Paul did well among young Republican voters. They were his strongest constituency, backing him by 61%-19%. His second-strongest constituency was the generation of retirement age; he barely won the adults between age 35 and 64.

According to Hubert Humphrey, "It was once said that the moral test of Government is how that Government treats those who are in the dawn of life, the children; those who are in the twilight of life, the elderly; and those who are in the shadows of life, the sick, the needy and the handicapped." It would seem that the first two groups have a special fondness for libertarians or paleoconservatives who would cut funding for the services that they receive. But of course, the sample of Republican primary voters in Kentucky doesn't represent the state's population, let alone the nation's. This result simply illustrates that there are pools of libertarian and other non-mainstream young voters (e.g., strong environmentalists) who matter when the total number of votes is low.

Second, I happen to know the guy whom Paul defeated, Trey Grayson, because he has been a strong leader for civic education and youth civic engagement. He focused on that topic in graduate school and then worked hard on it as Kentucky's Secretary of State. I think Democrats are better off with Paul on the ballot in November, although it's a risky business. For proponents of youth engagement, Grayson would have made a great Senator. Ironically, young people from his own party helped deny him that opportunity.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:08 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 24, 2010

three Europes

1. A steep and crooked alley, armspan's width, cobbled; a tiny car squeezed between walls of stone or stucco that are studded with iron grilles, draping flowerpots, drying towels, and sleeping cats.

2. A soccer field reached by a pedestrian bridge that spans four lanes of traffic; giant billboards at the roundabout; terraces of apartment blocks rising on the hills opposite with anarchist graffiti on their lower walls and satellite dishes on their roofs.

3. Long, cool corridors, subdued indirect lighting, brushed steel and blond wood; panini, quiche, and bagels at the cafe; quadrilingual instructions on the assorted recycling bins.

I know there are many more Europes; these are the three that stick in my mind on my first day back in the US.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:18 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 21, 2010

Heathrow after a red-eye

Like fat roaches stopped

When the kitchen light flicks on

Jets on the tarmac

Posted by peterlevine at 7:13 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 20, 2010

rethinking the humanities

(Lisbon, Portugal) I am here for a conference on the humanities. A major question was whether they are "in crisis"--because of falling budgets and enrollments, or deep epistemological and cultural discontents, or technology and pop culture, or all of the above. My own talk was a precis of my book, Reforming the Humanities. Some highlights from the other speakers ....

In the course of his wide-ranging talk, David Damrosch interpreted several texts that happened to be hip-hop (or, in one case, "hip-pop") videos by singers/entrepreneurs who have migrated across cultural lines, e.g., from Beirut to Paris to Montreal. In the 20th century, a particular conception prevailed of the humanities as purely textual, professional, and located within specific cultures. For example, English professors wrote sole-authored books about novels written by Anglophone authors. Even as they took opposite positions regarding interpretation and authorship, Jacques Derrida and Northrop Frye both wrote dense, unillustrated texts about other texts, for professional colleagues. The future, however, lies with mashups and multimedia and with artists and interpreters who create businesses or other organizations. That was also the case in our past. The typical condition of the arts and humanities is to mix up written text, image, and orality--and cultural products typically cross national lines. Humanists' specific skills of interpretation and selection remain essential.

Antonio Souza Ribeira gave a penetrating talk about the role of the humanities, virtually free of jargon yet deeply informed by serious thinkers from Goethe to Habermas. My favorite quote (paraphrased): "A friend of mine, an engineering professor whom I have no reason to doubt is intelligent, said to me, 'What a privilege to be paid to read novels!'" Prof. Souza's argument: the role of the humanities is to challenge instrumental, means/ends rationality and the divisions among the economy, politics, and society/culture that cause people to think as this engineer does. The humanities have a "reconstructive" task, concerned with the present and the future and not merely understanding the past.

Richard Wolin gave an erudite but also passionate defense of a tradition that began with Renaissance humanism, matured with the Republic of Letters in the Enlightenment, and received a full theoretical justification with Kant. This tradition (as I would summarize it) involves developing moral autonomy, good judgment, and civic skills and ethics through the close and collaborative reading of challenging texts. Part of the reason for its decline--Wolin suggested, and I agree--is that humanists themselves doubt this tradition's value. He specifically cited post-structuralism as an attack on the tradition from within.

As we spoke, apparently the budgets of Portuguese faculties of arts and letters were under review. There is a financial crisis today even if not a philosophical one.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:02 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 19, 2010

in London

I am on a long journey: Boston -> Washington -> Boston -> London -> Lisbon, all within 48 hours. I had a layover at Heathrow that was long enough to allow me a quick trip to Paddington and then back to the airport. I walked a circuit of a few miles: Paddington to Notting Hill Gate, Hyde Park, South Kensington, Gloucester Road, Kensington High Street, Kensington Church Street, Bayswater Road, and back to Paddington.

I have spent about eight years in this city, including almost every summer from ages 0-20, plus five school years. Nostalgic by temperament, I am fond of London for quasi-objective reasons as well as strictly personal ones. Actually, it would be hard for anyone to deny the elegance of Kensington on a cloudless spring day. But I admire much more of the city than its wealthiest squares and mewses. London has been a polyglot entrepot since Chaucer's day, when Lombards and Flemings were especially important residents, and it has become an amazingly multiracial and multicultural metropolis in the 21st century.

The underlying English culture is absorptive and adaptive. London changes faster than New York (the supposed capital of creative destruction) because both market and state have the power to reorganize this city in each generation. After just a few years away, all the retail chains seem new, people eat and drink different things everywhere, the transportation system has been sold, resold, and reconfigured, the slang is new, uniformed workers speak different languages (I heard lots of Polish and Spanish today), and whole new neighborhoods seem to have sprung up. Yet the bricks are still made of London Clay, which the Romans used here. Ladies still pull tartan shopping baskets home from Sainsbury's. Stinging nettles still force their way between railroad tracks and garden sheds. The morning streets still smell of wet cement, curry, and beer.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:35 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 18, 2010

Brad Rourke's PACE paper on the executive branch and civic engagement

(Washington, DC) In March, courtesy of Philanthropy for Active Civic Engagement (PACE), I was able to meet with White House staff to discuss strategies for public engagement and civic renewal. The meeting was informed by a fine draft paper by Brad Rourke. Brad has revised and expanded the draft to produce "An Evolving Relationship: Executive Branch Approaches to Civic Engagement and Philanthropy." I strongly recommend it as a historical and conceptual overview of efforts--nonpartisan, even though they started with presidential administrations from George H.W. Bush to Barack Obama--to enhance citizen engagement. The goal is for citizens to "do things for themselves--identifying and solving community problems, discussing and choosing between different possible solutions, making tradeoffs." As Brad notes:

Since the 1970’s, public life has become increasingly professionalized. Scholars have noted a tendency for some government initiatives to approach citizens as if government or other institutions are doing the problem-solving, and citizens are receiving the benefits of those solutions. From this standpoint, citizens can best provide 'input,' and are ultimately the “customers” of institutional actions, even actions by citizens' organizations.

However, a more citizen-centric view might be that government and other institutions best come into play in order to do those things citizens cannot do themselves.

[...]

This approach to civic engagement is nascent. At the same time that there is a new energy behind collaboration and participation, there is also new energy behind more negative social forces. Partisanship and polarization are high. Rhetoric in public life is heated. Trust in institutions (not just government) is at all-time lows, as is trust in one another. ... For those who care about civic engagement and participation, this is a time that holds both potential and risk.

Rasmussen recently surveyed a national sample and found: "44% believe volunteer activities and organizations are more likely than new government programs to bring about the change needed in the United States. Thirty-seven percent (37%) take the opposite view and say that new government programs and policies will bring about the needed change. " That result could be taken as evidence of conservatism, but there is a long tradition of grassroots centrist and even leftist activism that makes the same assumption. Michelle Obama, at least year's National Conference on Volunteering and Service, hammered away on the theme that positive change comes from the bottom up, not the top down. Brad's paper is basically about efforts from the very top--the White House--to enable bottom-up change.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:49 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 17, 2010

Zadie Smith, White Teeth

- "Every moment happens twice: inside and outside, and they are two different histories."

Zadie Smith finished her first book, White Teeth, while she was an undergraduate. It's much more than a prodigy's tour de force; I think it's a fine and lasting novel.

It is elaborately plotted. The events span the period 1857-1999 and create a complex and deliberate pattern, full of symmetries and recurrent patterns. The whole structure encompasses three extended families (Bangladeshi Muslim, West Indian/British, and Anglo-Jewish) plus numerous well-developed hangers-on. As an example of what geometers would call a "reflection symmetry," the two Bangladeshi twin brothers grow up in the East and the West, each embracing the other's hemisphere, and they both make love to the same woman on the same day, whose child could therefore be either one's. As an example of a "rotational symmetry": at one point, disgruntled teenagers from each family are living with the next. Guns are fired in parallel situations in 1857, 1945, and 1992.

This whole structure could be considered artificial and mannered--especially when everything comes together neatly in the denouement. Smith is interested in no less a matter than Fate, the sense that life is pre-plotted. This seems especially salient in the lives of immigrants from the former colonies. Their lives are symmetrical, recurrent. Fate is also an explicit topic in at least three cultures that Smith explores and counterposes: Islam, Christian fundamentalism, and molecular biology.

I am not as interested in Fate, but I love the elaborate structure for a different reason. As many have noted, Smith is a genuine genius at mimicking and sympathetically portraying diverse people. Who am I to say whether she can see the world like an 85-year-old Jamaican Jehovah's Witness? But I can vouch for her precise evocation of a secular Jewish teenage boy with academic parents living in North London in the 1980s. I was there, and she's got that demographic spot on. All the other characters--who range magnificently across continents, religions, generations, races, and classes--seem entirely plausible.

What happens when you create an artificial structure of events and portray it from myriad perspectives, sympathetically and without the imposition of your own voice? That is a liberal political achievement, because it respects individuality and difference and refuses to boss people around, even in the imagination. It is also an artistic achievement. "For me," Nabokov wrote, "a work of fiction exists only insofar as it affords me what I shall bluntly call aesthetic bliss, that is a sense of being somehow, somewhere, connected with other states of being where art (curiosity, tenderness, kindness, ecstasy) is the norm." Nabokov's recipe is: curiosity, which makes you describe all kinds of people and objects; tenderness, which makes you love them all; plus aesthetic pleasure, which arises when the first two are achieved harmoniously and elegantly. Smith is an artist in the true Nabokovian sense.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:49 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 14, 2010

creating informed communities (part 5)

This is the fifth of five strategies proposed to achieve the goals of the Knight Commission on the Information Needs of Communities. See Monday's post for an overview.

Strategy 5: Organize People to Defend the Knowledge Commons

The Knight report does a great job of showing that healthy communities need information. Information is a "public good," in the economist's sense, because excluding people from its benefits is difficult and expensive once the knowledge has been produced. Generating and protecting public goods raises special challenges for which we need effective, grassroots advocacy organizations.

The main challenges facing public goods are, first, that individuals may not be motivated to produce things that benefit everyone (when instead they can “free-ride” on others’ labor), and second, that individuals, firms, and governments may be tempted to privatize public goods for their own advantage. Today, many knowledge artifacts that once would have been rivalrous can be digitized, posted online, and thereby turned into public goods. On the other hand, knowledge can be privatized and monetized, as when intellectual property is over-protected or when university-based research is influenced by corporate funding. It is also possible for knowledge to be under-produced, if there are insufficient incentives to develop it and give it away. For example, too little research is conducted on diseases that affect the poorest people in the world.

Civic knowledge--knowledge of relevance to public or community issues--does not come into existence automatically, nor is it safe from anti-social behavior. The documents in a town archive, the reporting that filled a traditional town newspaper, and the artifacts in a local museum all took money and training to produce, to catalog, and to conserve. Once produced, these goods are fragile. They can literally decay or burn, and they are subject to manipulation or inappropriate privatization.

For example, access to state court decisions in the United States is provided exclusively by private firms, mainly the West Publishing Company and LEXIS/NEXIS. The public’s interest in affordable and convenient access to public law would be undermined if these firms over-charged or provided poor quality.

In 1998, with the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act, Congress extended most existing copyrights in the United States for 95 years. Congress thus granted monopoly ownership to works that had been created as long ago as 1903--requiring anyone who wanted to use these works to locate the copyright holder, seek permission, and pay whatever fee is demanded--and asserted a right to extend copyrights as frequently and for as long as it liked. In his dissenting opinion to the court decision that upheld this law, Justice Breyer wrote, “It threatens to interfere with efforts to preserve our Nation’s historical and cultural heritage and efforts to use that heritage, say, to educate our Nation’s children” (537 U.S. 26, 2003, 26). If Justice Breyer was correct, the Sonny Bono Act was an example of knowledge of civic value being turned from a public good into a private commodity by state power at the behest of private interests.

Given such threats, we need associations that play the following roles:

- 1. Advocacy. Policies to benefit the “knowledge commons” would include protection of free speech, appropriate copyright laws, public subsidies for libraries and archives, and public funds to digitize archives. Beneficial policies are public goods that often lose out to private interests that profit more tangibly from selfish policies. For example, everyone benefits from free access to historical texts, but a few companies profit much more substantially from their own copyrights. Independent, nonprofit associations can rectify this imbalance by recruiting voters, activists, and donors to promote the public interest in government. The American Library Association, for example, has been a strong advocate for knowledge as a commons.

2. Alliances. Communities across the country have information needs and valuable, accumulated public knowledge. Attacks on free information anywhere are threats to free information everywhere. "We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly." That is what Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., wrote as he and his colleagues built a civil rights movement. As a result of their work, when civil rights were viciously repressed in one location, people got on buses from other places to come and protest. We may not need bus trips, but we do need people in each community to feel that the information commons in other places matters to them as well. In practical terms, that requires networks of associations that have working ties.

3. Education, broadly defined. People do not automatically acquire an understanding and appreciation of valuable civic knowledge, nor the skills necessary to produce and conserve such knowledge. Each generation must transmit to the next the skills, motivations, and understanding necessary to preserve knowledge as a commons. Government-run public schools may have a role in this educational process, but they should not monopolize it. A more pluralistic and independent education depends on private nonprofit associations that recruit and train people to be community historians, archivists, naturalists, artists, or documentary filmmakers (among other roles).

Posted by peterlevine at 1:54 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 13, 2010

creating informed communities (part 4)

This is the fourth of five strategies proposed to achieve the goals of the Knight Commission on the Information Needs of Communities. See Monday's post for an overview.

Strategy 4: Generate Public "Relational" Knowledge

Citizens need facts about organizations, leaders, and issues. They need rival interpretations of those facts, and deliberative public judgments based on such interpretations. Citizens also need to understand the relationships among people, organizations, and issues. All competent civic and political actors, since the beginning of time, have held in their heads implicit "network maps" that link ideas and individuals in their community. They know, for example, that if they want to talk to the leader of the town, they should go through an accessible individual whom the leader regularly consults. If someone raises a local issue, they can link it to relevant organizations and to related issues.

In recent years, three developments have underlined the importance of such thinking. One is the "The New Science of Networks," as Albert-László Barabás subtitles his book Linked. This science is the mathematical exploration of nodes and network ties as they arise under various conditions, and it has yielded powerful insights, such as the value of "weak ties" and the importance of individuals who connect disparate communities.

The second development is the enormous popularity of social networking sites like Facebook, which are driven by webs of relationships. These sites have popularized the concept of network ties and underlined their importance. But Facebook and other corporate social networks keep the relational data--the "network map"--to themselves. They do so to protect users' privacy and also to give themselves a valuable asset. For example, to reach everyone at Tufts who has a Facebook account, we must pay Facebook to advertise. We cannot see a list of users who have Tufts connections.

The third development is the art of relational organizing. Relational organization groups such as the Industrial Areas Foundation and the PICO and Gamaliel Networks do not begin with clear and fixed goals. They decide what their causes should be by means of long periods of listening and discussing within diverse networks that they carefully nurture. They are highly skilled at mapping networks to identify power relationships, excluded groups, and key hubs. [See, e g., Mark R. Warren, Dry Bones Rattling: Community Building to Revitalize American Democracy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001, pp. 31-2..

The next step is to democratize the possession of effective network maps, so that they do not exist only in the brains of skilled organizers or on the servers of Facebook and MySpace. Informed communities should have access not only to discrete facts and lists of organizations--nor should they be satisfied with geographical maps that show the physical location of organizations. They should be able to build and consult public network maps that allow them to identify power, influence, exclusion, division, and other attributes of relationships, not of individuals.

Working with Lew Friedland and his colleagues at Community Knowledge Base, we have been experimenting with public network maps in two contexts:

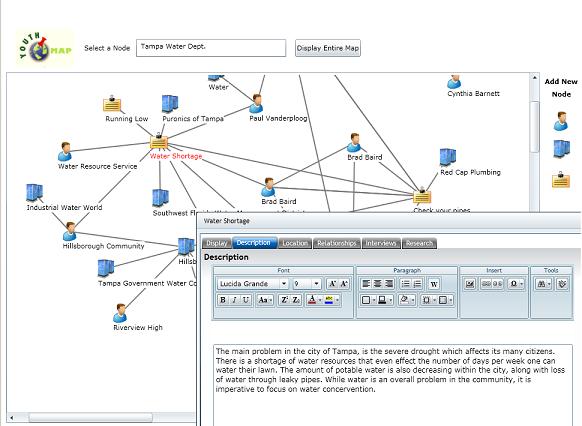

- We have begun to create computer-based games in which classes of high school or middle school students quickly generate network maps of local issues, organizations, and people. The following is part of a real map concerned with water issues in the Tampa, Florida area. It was quickly created by a class of 9th graders, who pooled their knowledge to produce a sophisticated understanding. (One node is open to reveal notes the student has typed.)

- We are also in the midst of creating an open network for the Boston metro area in which nodes will be organizations or issues, and anyone will be able to add to the map, use it to recruit volunteers, and navigate it to explore the structure of this region's civil society. It's not ready for a public launch, but one can explore the map here.

These are just preliminary experiments. They do not yet harness the full potential of network analysis and visualization, nor the power of computers to harvest network data automatically from websites. My basic recommendation is that governments and foundations should invest in providing transparent relational data along with the other information that is already online.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:23 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 12, 2010

creating informed communities (part 3)

This is the third of five strategies proposed to achieve the goals of the Knight Commission on the Information Needs of Communities. See Monday's post for an overview.

Strategy 3: Invest in Face-to-Face Public Deliberation

Today I focus on a particular recommendation in the Knight report, number 13, which is: "Empower all citizens to participate actively in community self-governance, including local 'community summits' to address community affairs and pursue common goals."

Face-to-face discussions of community issues have been found to produce good policies and the political will to support these policies, to educate the participants, and to enhance solidarity and social networks. In the terms of the Knight Report, they turn mere information into public judgment and public will. I'm still moved by the Australian participant in a planning meeting who said, "I just can't believe we did it; we finally achieved what we set out to do. It's the most important thing I've ever done in my whole life, I suppose" (quoted in Gastil and Levine 2005, p. 81).

I agree with the Report: "As powerful as the Internet is for facilitating human connection, face-to-face contact remains the foundation of community building." The whole array of online communications contribute to civil society, but dedicated online deliberative spaces--despite some potential for improvement--have been basically disappointing so far. The open ones are subject to pathologies that you don't often see in the physical world. For example, the White House open government forum on transparency was almost hijacked by proponents of legalizing marijuana (PDF, p. 9). In a face-to-face setting, especially in a discrete physical community, it would be very difficult to swarm a public session in that way.

In order to make real-world deliberations work, several conditions must be met. There must be some kind of organizer or convening organization that is trusted as neutral and fair and that has the skills and resources to pull off a genuine public deliberation. People have to be able to convene in spaces that are safe, comfortable, dignified, and regarded as neutral ground.

There must be some reason for participants to believe that powerful institutions will listen to the results of their discussions. They may be hopeful because of a formal agreement by the powers that be, or even a law that requires public engagement. Or they may simply believe that their numbers will be large enough--and their commitment intense enough--that authorities will be unable to ignore them.

There must be recruitment and training programs: not just brief orientations before a session, but more intensive efforts to build skills and commitments. Ideally, moments of discussion will be embedded in ongoing civic work (volunteering, participation in associations, and the day jobs of paid professionals), so that participants can draw on their work experience and take direction and inspiration from the discussions. There must be pathways for adolescents and other newcomers to enter the deliberations.

We have examples:

- Bridgeport, CT--an old port and manufacturing city of 139,000 people--was a basket case in the 1980s. It was hard hit by the loss of manufacturing jobs, crime, and the flight of middle-class residents to the suburbs. The city literally filed for bankruptcy in 1991. The next mayor was sentenced to nine years in federal prison for corruption. The schools were so troubled that 274 teachers were arrested during a strike in 1978.

Bridgeport is now doing much better, to the point that its school system was one of five finalists for the national Broad Prize for Urban Education in both 2006 and 2007. A major reason for Bridgeport’s renaissance is active citizenship.

In 1996, a local nonprofit group called the Bridgeport Public Education Fund (BPEF) contacted organizers who specialize in convening diverse citizens to discuss issues, without promoting an ideology or a particular diagnosis. No one knows how many forums and discussions took place in Bridgeport, or how many citizens participated, because the 40 official “Community Conversations” were widely imitated in the city. But it is clear that at least hundreds of citizens participated; that many individuals moved from one public conversation to another; and that some developed advanced skills for organizing and facilitating such conversations. A community Summit convened in 2006--fully ten years after the initial discussion--drew 500 people. The mayor, the superintendent, the city council, and the board of education had agreed in advance to support the plan that participants developed. [See Will Friedman, Alison Kadlec, and Lara Birnback, Transforming Public Life: A Decade of Citizen Engagement in Bridgeport, CT, Case Studies in Public Engagement, no.1, Public Agenda Foundation, 2007; and Elena Fagotto and Archon Fung, “Sustaining Public Engagement: Embedded Deliberation in Local Communities,” an Occasional Research Paper from Everyday Democracy and the Kettering Foundation, 2009]

So far, I have described talk, but the civic engagement process in Bridgeport involves work as well. Each school has an empowered leadership team that includes parents along with professional educators. The professionals take guidance from public meetings back into their daily work. People who are employed by other institutions, such as businesses and religious congregations, also take direction from the public discussions. Meanwhile, citizens are inspired to act as volunteers. The school district has a large supply of adult mentors, many of them participants in forums and discussions. In turn, their hands-on service provides information and insights that enrich community conversations and improve decisions. Bridgeport’s citizens have shown that they are capable of making tough choices: for instance, shifting limited resources from teen after-school programs to programs for younger children. There is much more collaboration today among businesses, nonprofits, and government agencies. Everyone feels that they share responsibility; problems are not left to the school system and its officials. The School Superintendent says, “I’ve never seen anything like this. The community stakeholders at the table were adamant about this. They said, ‘We’re up front with you. The school district can’t do it by itself. We own it too.’” [Friedman, Alison Kadlec, and Lara Birnback]

- Hampton, VA, is an old, blue-color city of about 145,000 people. Like its fellow port city of Bridgeport, 465 miles to the north, Hampton has struggled with deindustrialization, although Hampton benefits from Army, Air Force, and NASA facilities within the city.

When Hampton decided to create a new strategic plan for youth and families in the early 1990s, the city started by enlisting more than 5,000 citizens in discussions that led to a city-wide meeting and then the adoption of a formal plan. “Youth, parents, community groups, businesses, and youth workers and advocates … met separately for months, with extensive outreach and skilled facilitation.” [Carmen Sirianni and Diana Marginean Schor, “City Government as an Enabler of Youth Civic Engagement: Policy Design and Implications,” in James Youniss and Peter Levine, eds., Engaging Young People in Civic Life (Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 1999)]

The planning process ultimately created an influential Hampton Youth Commission (whose 24 commissioners are adolescents) and a new city office to work with them. The Youth Commission sits on top of a pyramid of civic opportunities for young people. There are also community service programs that involve most of the city’s youth; empowered principals’ advisory groups in each school, a special youth advisory group for the school superintendent, paid adolescent planners in the planning department, and youth police advisory councils whom the police chief contacts whenever a violent incident involves teenagers. Young people are encouraged to climb the pyramid from service projects toward the citywide Commission, gaining skills and knowledge along the way. Political engagement is so widespread that almost 80 percent of Hampton’s young residents voted in the 2004 election, compared to 43 percent in Virginia as a whole. The system for youth engagement won Hampton Harvard’s Innovation in Government Award in 2007.

Engagement is not limited to young residents. When Hampton’s leaders decided that race relations and racial equity were significant concerns in their Southern community that was about half White and half African American, they convened at least 250 citizens in small, mixed-race groups called Study Circles. The participants decided that there was a need to build better skills for working together across racial lines, so they created and began to teach a set of courses--collectively known as “Diversity College”--that still trains local citizens to be speakers, board members, and organizers of discussions. [William R. Potapchuk, Cindy Carlson, and Joan Kennedy, “Growing Governance Deliberatively: Lessons and Inspiration from Hampton, Virginia,” in Gastil and Levine, 2005, p. 261]

Hampton’s neighborhood planning process has broadened from determining the zoning map to addressing complex social issues. Planning groups include residents as well as city officials, and each may take more than a year each to develop a comprehensive plan. Like the young people who helped write the youth sections of the City Plan, the residents who develop neighborhood plans emphasize their own assets and capabilities rather than their needs. There is an “attitude of ‘what the neighborhood can do with support from the city’ rather than ‘what the city should do with the neighborhood watching and waiting for it to happen.’” [Potopchuk, Carlson, and Kennedy, p. 264.]

Hampton has thoroughly reinvented its government and civic culture so that thousands of people are directly involved in city planning, educational policy, police work, and economic development. Residents and officials use a whole arsenal of practical techniques for engaging citizens—from “youth philanthropy” (the Youth Commission makes $40,000 in small grants each year for youth-led projects), to “charrettes” (intensive, hands-on, architectural planning sessions that yield actual designs for buildings and sites). The prevailing culture of the city is deliberative; people truly listen, share ideas, and develop consensus, despite differences of interest and ideology. Young people hold positions of responsibility and leadership. Youth have made believers out of initially suspicious police officers, planners, and school administrators. These officials testify that the policies proposed by youth and other citizens are better than alternatives floated by their colleagues alone. The outcomes are impressive, as well. For example, the school system now performs well on standardized tests.

I would draw the conclusion that is also implicit in the title of Carmen Sirianni's recent book, Investing in Democracy. You can't get "community summits" and other forms of excellent engagement on the cheap. They take a long-term effort and resources that are normally a mixture of money, policies, and people's volunteered or paid time.

Posted by peterlevine at 3:40 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 11, 2010

creating informed communities (part 2)

This is the second of five strategies proposed to achieve the goals of the Knight Commission on the Information Needs of Communities. See Monday's post for an overview.

Strategy 2: Universities as Community Information Hubs

Most people and organizations that produce, exchange, and interpret information have their own axes to grind. They have ideological or philosophical commitments as well as interests to promote--and that is perfectly appropriate. Yet we have always been better off when a few institutions declare neutrality. They volunteer for the role of promoting high-quality discussion, debate, and analysis and they try not to drive everyone to a particular conclusion.

An example was the metropolitan daily newspaper as envisioned in the Progressive Era. I realize that no newspaper was ever fully neutral, nor was neutrality ever the highest criterion of excellence. But metro dailies adopted rules and procedures that were influenced by the ideal of neutrality, such as the separation of their editorial pages from their news pages. They could be held accountable for fairness, balance, objectivity, and accuracy. And--to varying but important degrees--they did enhance public dialogue with neutral information.

But the metropolitan daily newspaper is in grim condition today. Public broadcasting stations have a similar mission--and NPR's audience is rising fast, even as newspapers falter--but broadcasters can't play this role alone. Nor can civic associations like the League of Women Voters; that sector is also in decline.

Universities must step up. As the folks at Community Wealth note, "Institutions of higher education have an obvious vested interest in building strong relationships with the communities that surround their campuses. They do not have the option of relocating and thus are of necessity place-based anchors. While corporations, businesses, and residents often flee from economically depressed low-income urban and suburban edge-city neighborhoods, universities remain."

Moreover, higher education is not just any sector with $136 billion in spending and $100 billion in real estate holdings. The business of colleges and universities is the production and dissemination of knowledge and the promotion of dialogue and debate. They provide an impressive infrastructure for serving their communities' information needs. And some are already excellent models.

- Portland State University in Oregon has chosen the motto “Let Knowledge Serve the City.” Since the early 1990s, the University has tried to align much of its teaching, research, and outreach to address specific issues in the city. A hallmark of its approach is lengthy, ambitious, multi-year projects that involve formal partnerships between several units within the university and several community-based organizations or networks and local governmental agencies.

Over a five-year period, as part of one coherent effort to protect a watershed (composed of urban streams), numerous classes of PSU students collected environmental and social data, educated local children and developed high school curricula, created videos, facilitated public discussions of the watershed, and directly cleaned up wetlands and constructed facilities. These classes did not work alone but in close cooperation with each other and with a large array of civic organizations [Dilafruz R. Williams and Daniel O. Bernstine, “Building Capacity for Civic Engagement at Portland State University: A Comprehensive Approach,” in Maureen Kenny, ed., Learning to Serve: Promoting Civil Society through Service Learning (Volume 7 of International Series in Outreach Scholarship), Springer, 2002, pp. 261-2].

PSU brings impressive resources to such work: 17,000 students, scholars and laboratories, purchasing power and facilities--none of which can be picked up and moved to another location. The university and the city share a fate, and the university understands that. Its commitments extend well beyond watersheds: its partnership with city schools is equally ambitious, and there are other examples. The university has encouraged its faculty to deliberate issues that arise when an educational institution addresses a city’s problems, using Study Circles as the format for these discussions. [Williams and. Bernstine, pp. 270-274.]

Certain networks exist to promote such work nationally, notably Campus Compact (an association of 1,000 college presidents who have committed to "lead a national movement to reinvigorate the public purposes and civic mission of higher education"); the American Democracy Project of the American Association of State Colleges and Universities (AASCU); and The Democracy Imperative. Land-grant universities have an especially strong heritage of local public service and a remarkable resource in their extension offices, which exist in virtually every county in the United States.

But significant reforms would have to be achieved before colleges could provide community information hubs.

1. They would have to accept this as one of their important missions, not only in abstract statements, but as a matter of real investment. Providing timely information of local relevance and with input from neighbors trades off against other intellectual pursuits. Overwhelmingly, rewards and prestige flow to scholars whose work is original and generalizable. Communities need work that is true, relevant, and accessible. You can do some of both, but you can't add the local work without subtracting a bit of something else. Creating community information hubs within higher education requires at least a modest shift of priorities.

2. They would need to aggregate the scattered knowledge produced by their professors, students, and staff. One of the advantages of the traditional metro daily newspaper was its format--a manageable slice of information every day, with the top news on the front page, a few hundred words of debate in the letters column, and space for the occasional in-depth feature. In contrast, a great modern university produces a flood of material for an array of audiences. Universities need to think about common web portals that accumulate and organize all their work relevant to their physical locations.

3. They would need appropriate principles and safeguards. You can do good by going forth into a community to study it, to portray it, and to stir up discussion about it. Or you can do harm. Much depends on how you relate to your fellow citizens off campus. Relationships should be respectful and characterized by learning in both directions. In this context, "research ethics" means far more than the protection of human subjects from harm; ethical research is directed to genuine community interests and needs and builds other people's capacity for research and debate. Like faculty, students must be fully prepared to do community service well, and held accountable for their impact. One tool that has been proposed to uphold such principles is a community review board (composed of community leaders, faculty, and students), which would have to approve all projects funded as "community service."

Most of the incentives that prevail in higher education work against becoming community information hubs (see this and this). When the incentives in a free and competitive market undermine the common good, some outside force should reward the behavior that we need. In this case, the federal and state governments and private foundations should channel some of their funds toward local information projects in higher education.

Posted by peterlevine at 2:47 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 9, 2010

creating informed communities (part 1)

The Knight Commission on the Information Needs of Communities has issued a report entitled Informing Communities: Sustaining Democracy in the Digital Age. This report makes 15 recommendations, including the following that are related to my work:

- Expand local media initiatives to reflect the entire reality of the communities they represent.

- Engage young people in developing the digital information and communication capacities of local communities.

- Empower all citizens to participate actively in community self-governance, including local “community summits” to address community affairs and pursue common goals.

- Emphasize community information flow in the design and enhancement of a local community’s public spaces.

- Ensure that every local community has at least one high-quality online hub.

- (see also the list of "potential action items" in an appendix to the report)

I have been asked to recommend ways that we can meet these objectives. This week, I plan to write five consecutive blog posts about strategies. As always, critical feedback is welcome.

Strategy 1: A Civic Information Corps: Using the nation’s "service" infrastructure to generate knowledge

Community service and the combination of service with academic study ("service-learning") have rapidly grown. Since the 1980s, civilian service has been institutionalized with funded programs, paid professionals, and rewards. In response to effective advocacy, the Federal Government founded the Points of Light Foundation in 1990, passed the National and Community Service Act of 1990, and launched AmeriCorps and the Corporation for National Service (later, the Corporation for National and Community Service) in 1993.

There is no single "corps" in AmeriCorps; instead, the Corporation funds intermediaries that include national nonprofits with diverse models and constituencies--City Year and Public Allies are two well-known examples--plus schools, universities, Native American nations, and local nonprofits. YouthBuild, the Peace Corps, and the Corps Network (a coalition of 143 Service and Conservation Corps) are additional components of the national service movement that happen not to receive AmeriCorps funds. Meanwhile, some large school districts and universities and one whole state (Maryland) have enacted service requirements for all their students. Several states and major cities also have official service commissions. Colleges and universities now look for prospective students with service experience.

Probably as a result of these incentives, opportunities, and requirements, three quarters of high school seniors reported volunteering at least "sometimes" by the year 2003, and 80 percent of incoming college freshmen reported having volunteered in high school. The Corporation for National and Community Service reports that about 8 million young adults (age 16-24) volunteered in 2008. These trends received an extra boost in 2009, when Congress passed the Edward M. Kennedy Serve America Act, which authorizes a tripling of AmeriCorps to 250,000 annual slots.

All these volunteers represent an important base for civic activity in the United States, at least potentially. "Service" activities range widely, and some have little connection to knowledge or information. It is not uncommon for young people involved in service to be bused to a park or an urban street and simply asked to pick up bottles or paint walls. AmeriCorps as a whole does not specify learning outcomes or require intellectually challenging opportunities for youth. Much emphasis is placed on the work performed, e.g., the number of homes weatherized. On the other hand, certain service projects generate public knowledge to an extraordinary extent. For example:

- There are 1,500 Bonner Scholars at 24 colleges and universities, all involved in community service and other forms of civic engagement, such as community research. Using a grant from the Corporation for National and Community Service (the Learn and Serve America program), the Bonner Foundation promotes the use of social media tools--such as wikis and videos--by all of its Scholars. Methods involve social-media trainings at all of its meetings and conferences, an elaborate online platform for shared work at each campus and nationally, and ten competitive subgrants to Bonner campuses that do more intensive work with social media. At the heart of the online platform is a wiki site with hundreds of documents on social issues, student projects, tools, and best practices. After receiving the Learn & Serve America grant, Bonner began to plan PolicyOptions, an additional wiki platform for news and policy background information that will enable campuses to establish local, campus-based PolicyOptions Bureaus that are affiliated through a national network, sharing information and a common web platform.

- With funds originally from the Cricket Island Foundation, we at CIRCLE funded young people in the Cabrini-Green Housing Projects in Chicago to document the full story of their community, which is nationally famous for its murder rate but has many other dimensions. Cabrini Connections today is rich with documentary videos, research reports, and photo essays.

The Knight Foundation report calls for a "Geek Corps for Local Democracy," consisting of college graduates who would "help local government officials, librarians, police, teachers, and other community leaders leverage networked technology." Corps members would educate local partners and also form a national learning network.

That sounds like a good idea, but I would relax two implied limitations. First, I would broaden eligibility well beyond college graduates. Just over half of adults between the ages of 20 and 29 have any college experience at all, and a majority of those do not hold four-year college degrees. A Greek Corps need not be limited to the quartile that is most successful (or privileged) in conventional ways. There are lots of talented individuals who have fallen off the college track, who would benefit from service, and who might contribute more than college graduates in terms of local knowledge and cultural savvy.

Second, I wouldn't limit their role to merely providing technical support for the nonprofit IT infrastructure. I would involve them in creating knowledge and culture. The best format might be a new "corps" (although I wouldn't call it a "Geek Corps," because there would be an emphasis on creativity and cultural diversity that we don't normally associate with geeks). Alternatively, the federal government might provide incentives for all kinds of service groups and organizations to focus on community knowledge. These groups would not have to focus narrowly in information or communications. If knowledge was an important byproduct of their work, they could join the national learning network, which would be separately funded and staffed.

In practical terms, if you organized after-school service activities for teenagers in, say, Chicago, and you emphasized community-based research, reporting, photo documentation, mapping, archiving local records online, or IT support for nonprofits, you could qualify as a "community knowledge producer." You would then be able to send a designee to meetings, apply for training opportunities, log onto a virtual learning network, and apply for specialized grants.

Posted by peterlevine at 4:35 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 7, 2010

my fellow readers

(Washington, DC) I have read almost every article in every issue of The New York Review of Books since about 1990. I enjoy it, and it's my continuing education. But some of the articles make me uneasy, in a peculiar way. Ostensibly reviews of new books, they are really profiles of great thinkers from the past. These geniuses typically rubbed shoulders with others who were equally worthy of caricatures by the late David Levine. Reading about these impressive cliques begins to make you feel that you've missed out. The reviewer, too, is formidably bright and learned, and he or she may drop the names of personal acquaintances who are just as famously smart and creative. One in-crowd is reviewing another.

More often than not, the essay suggests that the great mind in question did not quite pan out, had a flaw or a weakness, somehow disappointed. That can make you feel even more inadequate by comparison. Or we may read that the great writer depicted an ordinary or mediocre person with a sharply satirical or a wisely sympathetic eye: think Emma Bovary, Leopold Bloom, or Rabbit Angstrom. In such cases, an intellectually glamorous reviewer is describing a superstar writer whose subject stands far beneath them both. But where do we stand?

More often than not, the essay suggests that the great mind in question did not quite pan out, had a flaw or a weakness, somehow disappointed. That can make you feel even more inadequate by comparison. Or we may read that the great writer depicted an ordinary or mediocre person with a sharply satirical or a wisely sympathetic eye: think Emma Bovary, Leopold Bloom, or Rabbit Angstrom. In such cases, an intellectually glamorous reviewer is describing a superstar writer whose subject stands far beneath them both. But where do we stand?

It all makes me want to address my fellow readers. (This is the age of peer-to-peer communication, after all.) So I say to my peers: Very few of us are destined for the pages of The New York Review, neither as writers nor as subjects. But we pay for the thing. We too have thoughts and hopes, even if they are not worthy of a review. Also, those geniuses?--they wasted some of their time. They cut corners and doubted themselves and wrote a fair amount of schlock. There's nothing like a five-page digest of a life to make the whole thing seem Olympian, even with its itemized flaws. Devote that much space to any of us, let an Elizabeth Hardwick or a Tony Judt summarize our work and a David Levine turn our face into art, and we wouldn't look so shabby, either.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:15 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 6, 2010

YUM: a taste of immigrant city

Project PERIS (Partnering for Economic Recovery Impact through Service) is an ambitious and rather complicated initiative of Tufts and our partners in Somerville, MA--funded by the Corporation for National and Community Service. The idea is to go beyond episodic and uncoordinated "community service" to achieve substantial impact. The project combines research, consultation, planning, and hands-on service as a real partnership between a university and community agencies and nonprofits.

In concrete terms, the main elements of the project are a set of courses (3-4 per semester) that are co-taught by Tufts faculty and community leaders. Each course undertakes some combination of research and service. The "connective tissue" among the courses is a series of planning and reflection meetings that include participants from across Tufts and Somerville.

In one class that I've been tangentially involved with, Professor Jennifer Burtner and her students helped plan and launch a project that supports 13 immigrant-owned restaurants in Somerville. Their major service is the Yum! discount card. They have also studied and documented the participating restaurants, producing graphic art, ethnographic essays, professional-quality photographs, videos, posters, and A-frame billboards. Some of their material is collected on their class blog.

The ethnographic essays are particularly interesting because they look--superficially--like restaurant reviews. But the perspective is different. These are not assessments meant for consumers; they are descriptions of small institutions in their social context.

Overall, PERIS is producing a mass of high-quality information and culture, which may turn out to be its biggest contribution--especially if we can find ways to pull that material together.

Posted by peterlevine at 2:25 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 5, 2010

will the White House go all in?

At a book party for Robert Kuttner's A Presidency in Peril, guests debated whether the White House will actively and forcefully support Democratic congressional candidates this November.

The argument against: Democrats are going to lose seats compared to 2008, even if they manage to draw a majority of the popular vote. A loss of seats will be depicted as a loss, period. If pundits and politicians assert that the president tried to help his party but failed, he will be depicted as weak and unpopular. That perception will deplete his political capital for the 2010-2012 legislative sessions.

The argument in favor: Perceptions of the president matter, but they will be shaped by more fundamental factors than whether he is perceived to have campaigned for Democrats in congressional elections. (The unemployment rate will be far more important, for one thing.) By campaigning, he may be able to boost turnout and save some seats. Even if he doesn't, he can gain political capital by taking a risk for his party. And he can energize the Democratic side by showing that he is moved by principle and policy, not by short-term political considerations. Finally, by making principled arguments for progressive policies in 2010, he can lay the groundwork for majority support when (or if) the economy finally recovers.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:26 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 4, 2010

young people and trust in government

I was quoted on NPR's Morning Edition earlier this week, commenting on a new Pew survey that finds 32 percent of young adults trust the federal government. That's not exactly a resounding vote of confidence, but it's much higher than the level of trust observed in older people today. For instance, just one in five of the 65-and-older group trusts the feds. In my quotes, I attribute some of the difference to generational traits. We know from many other surveys--and from comparisons to surveys in past decades--that Americans born after 1985 tend to be more trusting toward government and other institutions (including corporations) than other recent generations were at the same age. They are also more likely to favor government action to promote equality and social welfare. See Peter Levine, Constance Flanagan, and Les Gallay, The Millennial Pendulum (pdf).

But three important caveats are in order. First, even though young people have more favorable views of big, adult-led institutions than their predecessors had since the 1960s, they continue to set records for lack of trust in fellow citizens. This is the "social trust" that is thought to promote all kinds of good outcomes, from democratic participation to health and well-being. It remains in deep decline.

Second, young people are surely still forming their opinions. They are not dyed in the wool. Pew finds that the whole population has some of the lowest levels of trust ever recorded in the government. Public anger comes on the heels of a deep recession and a series of bailouts. The research on Millennials' attitudes mostly predates the recession. By the time the dust settles, young people may conclude that the Obama Administration (which they played a major role in electing) helped them and the country, in which case their levels of confidence will rise. Or the Millennials may conclude that the feds fiddled while Rome burned, in which case their formative experiences will be sharply negative. The story is far from over, and it's way too early to make predictions about a whole generation (the youngest members of which are now turning five years old).

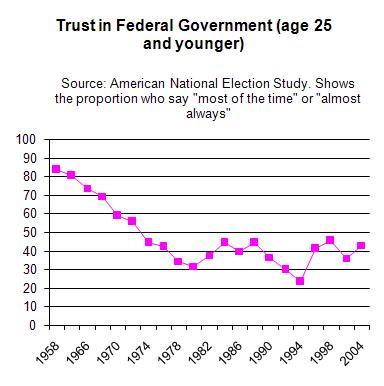

Third, we tend to compare Boomers, Xers, and Millennials with great interest, focusing on fairly small changes. That's because we have lots of comparable data on them. But if you take a longer view, it's clear that the big changes occurred four and five decades ago. At the height of the New Deal, the Fair Deal, and the New Frontier, vast majorities of Americans--young and old--trusted the federal government to do the right thing. After Watergate and Vietnam, trust has bounced up and down depending on the economy and other news, but it has remained in a whole new band. Where once trust was the norm, now distrust prevails. This change explains a great deal about the direction of national policy since 1970.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:16 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 3, 2010

Hirsh on how to save the schools

E.D. Hirsh's review of Diane Ravitch's The Death and Life of the Great American School System: How Testing and Choice Are Undermining Education is not very good--as a review. Ravitch's book is important, and Hirsch doesn't really analyze it. Instead, he uses the opportunity to argue for his own view. But his position is worth considering: it is orthogonal to the main debates in education.

The main debates concern incentives or pedagogy. That is, the two main strategies for improving schools are to change the rewards and punishments, or else to convince/educate teachers to act differently.

Strategies that involve incentives appeal to several types of reformers. Some want to test students and allocate resources according to the test scores (the NCLB approach). Some want parents to be able to choose schools for their own children and let the public money follow the kids. Some want to raise teachers' pay in order to motivate qualified people to enter and remain in the profession. All share the assumption that the government can't or shouldn't improve our 120,000 public schools by directly influencing the content of education in each one. We improve other sectors by shaping external incentives for innovation and impact, and the idea is to do the same with schools.

Strategies that involve pedagogy are equally controversial. The two main poles of this controversy are Deweyan progressivism versus traditionalism. Progressives are "child-centered" or "constructivist" (see my summary here). They want kids to shape their own learning according to their diverse interests and motivations--to be active participants in interpreting and creating knowledge and culture. Traditionalists worry that leaving children to make such decisions short-changes them. They think that students benefit from being told and explained things. Both sides want to influence our 120,000 schools by training or persuading our 3.5 million teachers.

Hirsch is a traditionalist on the question of pedagogy, but he has an alternative strategy for reforming schools. He focuses on the curriculum. This is his lever of change. For him, the curriculum is a set of things students should know: facts, concepts, names, dates, and places on the world map. Put another way, it is a set of texts that students should read and understand (texts that competently present the things that students should know). The curriculum as a whole should be:

- Transparent, a literal list, so that students from marginalized and disadvantaged backgrounds and the teachers who serve them can know what the kids need to learn.

- Uniform, because Hirsch argues that success in life requires knowing what everyone else is also expected to know. If that varies, mastery is impossible.

- Finite, because students can only absorb so much material, and they ought to have time left in the day for other activities.

Unlike proponents of vouchers and charters, Hirsch is perfectly willing to say that all schools should change the content of the education they provide. Unlike the proponents of various pedagogies, he doesn't trust in a strategy of changing what teachers do. He wants to redefine what they teach.

I have not made a study of the independent research on Hirsch's approach. In theory, it could work. The question seems strictly empirical to me. As an advocate for civic or democratic education, I care most about civic outcomes. I want to see students prepared to play active and effective roles in our public life. I do not take it for granted that the path to that outcome must itself be democratic or participatory. Maybe all kids should read The Federalist Papers and Letter from Birmingham Jail (and other texts), and that is all they need. I sort of doubt it, but I respect Hirsh for putting an alternative on the table.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:35 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack