« March 2010 | Main | May 2010 »

April 30, 2010

community organizing and public deliberation

Matt Leighninger, director of the Deliberative Democracy Consortium, has written a wise and inspiring paper called Creating Spaces for Change for the Kellogg Foundation. It is the product of several meetings in which community organizers interacted with people who define their roles as promoting public deliberation. The tensions between these two conceptions of "democracy"--and the potential for melding them--have interested me for many years. I've addressed the topic in published writings, e.g., here. But Matt's report breaks new ground.

Deliberative democracy first arose as a response to a blinkered notion of politics as mere power. The dominant view of political scientists during the 1950s and 1960s was that individuals and organizations want things. They have options, such as to vote, to contribute money, to run for office, to strike, to sue, or to threaten violence, and they make their choices in order to get as much of what they want as possible. Political outcomes are the result of many simultaneous choices.

Deliberative democrats criticized that theory from a moral perspective, saying that we should not be satisfied with policies that arise because individuals and groups try to get what they want. They may not want good things; their power is starkly unequal; and some of their tactics are unethical. Besides, people don't know what they want until they have communicated with others. So we should talk and listen before we try to get things.

But talk can be very harmful, as when evil dictators talk their followers into murderous action. Thus a crucial second step for deliberative democrats is to define some kinds of communication as better than others and to name the better kinds "deliberation." Typically, the hallmarks of deliberation include the diversity of the participants, their equality of influence, freedom of speech, openness and transparency, reasonableness, and civility.

There is now a field devoted to organizing tangible public deliberations at a human scale: meetings, summits, "citizens’ juries," community dialogues, moderated online forums, and various hybrids of these. They all involve convening diverse groups of citizens and asking them to talk, without any expectation or hope that they will reach one conclusion rather than another. The population that is convened, the format, and the informational materials are all supposed to be neutral or balanced. There is an ethic of deference to whatever views may emerge from democratic discussion. Efforts are made to insulate the process from deliberate attempts to manipulate it.

In contrast, activism or advocacy implies an effort to enlist or mobilize citizens toward some end. At their best, advocates are candid about their goals and open to critical suggestions. But they are advocating for something. Many advocates for disadvantaged populations explicitly say that deliberation is a waste of their limited resources. They note that just because people are invited to talk as equals, the discussion will not necessarily be fair. Participants who have more education, social status, and allies may wield disproportionate power. Individuals and groups who are satisfied with the status quo have an advantage over those who want change, because they can use the discussion to delay decisions. (They can "filibuster.")

Talking with people who hold different views can cause us to temper or censor our sincere views in order to avoid confrontation; and such self-editing reduces our passion and our motivation to act. Social movements that oppose injustice seem to arise when "homogeneous people … are in intense regular contact with each other." (Doug McAdam, John D. McCarthy, and Mayer N. Zald, 1996).

For their part, proponents of deliberation often see organized advocacy as a threat to fair and unbiased discussion; hence they struggle to protect deliberative forums from being "manipulated" by groups with an agenda. One tactic for this purpose is to select potential participants randomly (like a jury), so that it is impossible for an interest group to mobilize its members to attend. Overall, deliberation seems cool, cerebral, slow, and middle-class. Activism seems urgent, passionate, effective, and available to all.

Community organizing is a type of activism. It is concerned with just social outcomes (not just processes). But many community organizers have deep concerns about respecting all voices, including ideologically diverse ones, building trust and networks among fellow citizens, and developing civic skills that include skills of listening and collaborating. Thus the gap between deliberation and community organizing can be very small. After one meeting that Matt describes, Eduardo Martinez of the New Mexico Forum for Youth and Community (a community organizer) remarked, "We may use different terminology and have different local issues, but most of the discussion was about how similar our work is."

Another organizer, Jah'Shams Abdul-Mumin, nicely articulated the limitations of both fields in making a case for combining them: "The organizing community often treats people in a pejorative manner. Meanwhile, the deliberative democracy crowd includes a lot of extremely intellectual types. Neither group owns up to the things they can do better to relate to people."

There were, evidently, tough discussions about the value (if any) of neutrality and whether concern for social equality needs to be built into deliberative processes. There were also debates about what to call the whole field that includes both deliberation and community organizing. "Civic engagement" seems too dry; "citizenship" can be understood as exclusive and merely legal. Nobody knows what "deliberation" is, and "community organizing" has perhaps "been stretched so far over the last forty years that it has lost much of its meaning." But overall, there seems to have been much enthusiasm for the idea that issue advocacy, community organizing, deliberative democracy, and racial equity may be parts of one larger cycle or ecosystem--a "wheel of engagement," as some called it.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:25 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 28, 2010

honoring Dorothy Height

(Washington, DC) Today, at the National Press Club, CIRCLE is leading a significant conference on federal policy and civic skills. Some 70 federal officials, academics, and nonprofit leaders will participate, including 25 who have speaking roles as part of an elaborate program. We will also release a detailed new study of civic skills, showing who has skills, who lacks them, how they are changing, and why they matter.

I think that Dorothy Height's funeral will be exactly simultaneous with our conference. The President and other luminaries will eulogize her across town while we are in the National Press Club. I am sorry that we have lost Height, yet it seems appropriate to discuss civic skills on a day devoted to celebrating her life. No one among the great leaders of the Civil Rights Movement--and perhaps no one in American history--better understood the importance of our topic.

As early as 1952, when Height was invited to teach in India, she described her expertise as "the philosophy and skills of working with people in groups." A decade later, she led mixed groups of white and African American women in Mississippi who deliberated and worked together to address injustice. This is only one example in a lifetime of such difficult and successful work.

Height knew that the main purpose of activism and service was not to benefit those served, but to strengthen the capacity of the servers for democratic self-governance. As she said, "Without community service, we would not have a strong quality of life. It's important to the person who serves as well as the recipient. It's the way in which we ourselves grow and develop."

She also understood that opportunities to develop civic skills are highly unequal (a form of injustice that we describe in today's release). She said, "We have to improve life, not just for those who have the most skills and those who know how to manipulate the system. But also for and with those who often have so much to give but never get the opportunity."

Height's lifelong institutional home was The National Council of Negro Women. In her words, its "great strength is that it builds leadership skills in women." She launched the Dorothy Height Leadership Institute as part of the Council, and today it keeps her light aflame by developing the civic skills of young people.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:17 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 27, 2010

Civic Studies, Civic Practices Conference

Please join Tisch College and CIRCLE for this two-day gathering of educators and activists to explore the theory and practice of citizenship. Through interactive sessions, we will focus on "citizenship" as creativity, agency, and collaboration--not as a form of membership that separates those who are in from those who are out.

CALL FOR PROPOSALS

We invite proposals for 90-minute "learning exchanges," which may include short panel presentations with plenty of time for conversation, moderated discussions, workshops, readings, planning sessions, or other types of events. A list of potential topics is below, but we welcome all proposals that fit broadly and creatively within the key theme of the conference, Civic Studies, Civic Practices.

Please use this this form to submit your learning exchange concept. Once you've submitted your proposal, we will be in touch to discuss your proposal, answer any questions you might have, or help you flesh out your concept. Proposals should be submitted by a group of at least two people. Teams of scholars and practitioners are preferred.

TOPICS

Citizens and Citizenship - What sort of citizens do we want? What knowledge, actions, and beliefs are important for strong citizens? What actions have citizens taken to actively engage in democratic practices? What institutional structures promote meaningful and engaged citizens? What knowledge, skills, and attitudes could transfer to global citizenship? Which may not? How does in-group and out-group status both define and limit citizenship?

Scale - How can strong/successful civic practices be scaled up and out? Is this a useful focus for civic work?

Civic Studies - Is this a useful field? What are its characteristics, boundaries, and limits? What is its potential theoretically and practically?

Political Reform - What changes in laws and policies are needed to strengthen active citizenship? What should we do to achieve those changes?

Civic Practices - Sessions on particular practices or methods, which may involve - for example - community organizing, media production, deliberation, reflection, or service.

Civic Education - How can we begin to address civic education in an era of education spending reduction, No Child Left Behind and Race to the Top?

PARTICIPANTS

Scholars, students, activists, educators and others interested in this topic are welcome to use this form to register or to submit a presentation proposal.

TIMING

July 23, 10 am through July 24, 4 pm

LODGING

Participants are responsible for their own lodging. Tufts dormitory rooms can be rented by the night in the summer. Please use this link to reserve a room

ABOUT THE CONFERENCE

The Civic Studies, Civic Practices Conference concludes the second annual Summer Institute of Civic Studies at Tisch College. This intensive, two-week interdisciplinary seminar brings together advanced graduate students, faculty and practitioners from diverse fields of study for challenging discussions about the role of civics in society.

Posted by peterlevine at 4:22 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

an extra's perspective

Last Thursday night, I boarded a flight from LA to Baltimore. I was coming from Seattle, where I had been meeting with veteran civil rights activists and community organizers, mostly young African American and Latino leaders from big cities. I was on my way to the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, where I would have conversations with William Kristol and Charles Murray, among others. The LAX-to-BWI flight was my chance for a little sleep between meetings.

Two young people recognized each other as they walked down the jetway to the plane. They had attended the same high school in Baltimore around the same time. The woman asked someone to switch seats so they could sit next to each other. That was bad news for me, because she ended up eight inches behind my head. But it was good news for them. They had so much in common--as I learned during the next five-and-a-half hours. Apartments not far apart, in the general vicinity of Culver City. Jobs in the media industry. Recent breakups. Jewish ancestry. Several drinks later, they were sharing their deepest hopes and dreams. As dawn broke over the east coast, they left the airplane holding hands.

It makes you think about how neat and happy stories feel to the people on the margins, those who are meant only to swell a progress, start a scene or two. The Fatted Calf was not so happy to learn of the return of the Prodigal Son. For every tearful reunion at the top of the Empire State Building, there are dozens of people in the elevator who are just trying to get on with their day. I didn't begrudge this new couple my night--it was more important to them than to me. But I wished their romantic comedy could have begun elsewhere than in seats 16C and D.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:31 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 26, 2010

using technology to cut the costs of college

Anya Kamenetz has a good article in The American Prospect about the need for colleges and universities to cut costs. The problem isn't just predatory lenders or cheap state legislatures; the real costs of college are rising far too fast and imposing unjust burdens on young people and their families. A major cause is probably the failure of higher education to achieve efficiencies that have cut costs in manufacturing and service industries. If everything else gets more efficient, but your activity doesn't, you become more expensive. That's the situation with both medical care and higher education.

Kamenetz is excited about initiatives like MIT's Open Courseware, which is an impressive repository of materials created at MIT that can be used free anywhere else. The materials include notes, syllabuses, readings, illustrations, problem sets, and assignments. It is generous and helpful for MIT to contribute in the way (sometimes at a cost of $15,000 or more for each course, as Kamenetz notes). But the benefits will be substantial only if (a) the expense of developing course materials is normally a significant component of tuition, and (b) "courseware" can be used effectively by faculty who didn't develop it in the first place. Both premises are possible, but I'm not overly optimistic.

I see two opportunities that might be more important.

First, I'm obsessed by the sheer number of people who are employed per student at particularly expensive colleges and universities. For instance, Harvard employs 2,163 faculty, 5,102 administrators and professional staff, and 4,800 clerical and technical workers for its 19,500 students. Only 18 percent of the total work force are professors. There are three students for every five workers. (I'm counting graduate students as students, even though most also teach, so the ratio is even higher.) Thus I wonder whether there could be significant efficiencies in administration. On the other hand, it may be that most of the administrative and professional staff are involved in externally funded research or clinical medicine, in which case shrinking their numbers doesn't cut the cost of education.

Second, I do see prospects for new types of course that would be based on computers, would be cheap per student, and would complement the rest of the curriculum. Imagine that we continued to offer a college education that was broadly similar to what we provide today, with seminars, lectures, labs, and office hours. But students were expected to take one course that was a large-scale simulation of a complex phenomenon. They might, for example, be asked to play various roles (appropriate to their majors) in a fictional town that faced a health emergency. Students would have to conduct research, plan, and communicate as part of playing this game. Developing it would be extremely expensive (if it was any good), but it could be offered nationally at a marginal price of just a few dollars per student. Small local teams of faculty could customize the game for their own campus.

I wouldn't want the computer to do the grading, but it could dramatically cut the costs of assessment by tracking the completion of assignments and scoring multiple-choice tests, leaving only writing to be hand-graded. If ten percent of students' credits were earned in such courses, the saving would be almost ten percent of tuition. And if these courses were offered in residential universities along with traditional seminars, lectures, and labs, there would be little loss of face-to-face learning and community.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:32 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 21, 2010

a long journey

Tonight, I fly to Seattle, Washington, for a meeting at the Gates Foundation. It will be a politically progressive gathering; entitled "The Color of Change," it is devoted to community organizing by young people from ethnic minorities. After somewhat less than 24 hours on the West Coast, I will take the red-eye flight to the other Washington, our Nation's Capital, for a meeting at one of the big-three conservative think tanks, the American Enterprise Institute. The topic, again, will be citizenship, albeit from a different perspective (with a focus on formal knowledge, military service, and the incorporation of immigrants) .

I have many thousands of miles and quite a bit of ideological spectrum to traverse between now and Friday evening (when I'll be back in Boston), so I'm not going to try to blog for the rest of this week.

Posted by peterlevine at 1:53 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 20, 2010

Syracuse is taking over

I am a native of Syracuse, NY, born and raised. I think my accent is "downstate" thanks to my parents. Our family was part of the Great Brooklyn Diaspora. But I grew up extremely familiar with what I considered a "Syracuse accent," characterized by distinctive vowels. Given the generally friendly culture of the place, the accent is best illustrated with phrases like, "Heeave a nice day!" Or "Keean you believe it, Sairacuse is in the Cheeampionship!"

As an adult, I have made Midwestern friends with similar accents, especially people from northern Illinois and urban Wisconsin. It turns out that something called the "northern cities vowel shift" began in the vicinity of Syracuse and has been spreading west, like acid rain but in the opposite direction.

On our western frontier, Nordic Minnesotans with their elongated o's. To our southeast, impregnable New Yuwalk City with all those extra w's. Canadians to the North, flinty New Englanders to the east (stingy with their "r's"), and Apallachia not so far southward across Pennsylvania and Ohio. But if nobody minds, we vowel-shifters will be heeyapy to keep on spreadin' out.

Prof. William Labov is the expert on the vowel shift, and he thinks it may have begun during the construction of the Erie Canal. I personally find the Chicago version just a little different, although I lack the technical training to know how to represent the distinction. Many European-Americans from Cleveland, Madison (that's Meeadison"), and Michigan sound to me strikingly like their counterparts from Syracuse. It's not only the vowels: if you grew up in Syracuse, there is something ineffably familiar about a row of double-decker wooden houses on a wintry side street in Madison. Maybe it all comes from living on drumlins or shoveling snow in May.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:31 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 19, 2010

reason and power in Julius Caesar

Julius Caesar is a play about power. The ultimate source of power is popular will--and not only in an official republic like Rome. Even a monstrous dictator like Stalin cannot physically kill millions of his own people; he must harness many others' wills.

Thus Julius Caesar begins: "Rome. A Street. Enter Flavius, Marullus, and certain Commoners." There follows a testy interchange between the Senators and the workers, in a public space, concerning political opinions. The people's choices are and will remain central to the plot.

Once Caesar is killed, the question becomes whether the people in the streets will follow his killers or his surviving allies. Brutus, one of the conspirators and a stoic philosopher (according to the play), has a specific view of how this should play out. The killing itself was appropriately a private act, undertaken secretly by Senators who, by bathing their hands in Caesar's blood, become a unit. (The play is interested in how different bodies can become one by pact: Portia says that Brutus, "By all [his] vows of love and that great vow / ... did incorporate and make us one.")

Brutus recognizes that he is accountable to the Roman people, so he appears before them to explain what he has done in private. "Public reasons shall be rendered / of Caesar's death."

The giving of rather abstract reasons is Brutus' preferred mode. He uses the word "reason" seven times in the play, twice in clear contrast to "affections." When he argues a point of military strategy, he states, "Good reasons must, of force, give place to better." The force, here, is the power of reason itself. (And the problem, again, is persuading the people. The "better reason" that Brutus offers is that "the people 'twixt Philippi and this ground / Do stand but in a forced affection.") Although Brutus deeply loves his idealized spouse Portia, when she dies, he takes no time for grief or lamentation. He thinks there is no good reason for such behavior. For Brutus, "reason" means highly cerebral, deliberative, and impersonal thought leading to right action.

Brutus is so confident of the people's reason that he allows Caesar's favorite, Mark Antony, to appear immediately after himself and with the body of the assassinated ruler. Mark Antony has a completely different view of how to persuade. He speaks with irony, misdirection, insinuation, and a barrage of rhetorical questions. He offers bribes in the form of Caesar's (alleged) legacies to the Roman people. Most powerfully, he enacts a public, physical demonstration, in which the people may directly participate.

- Then make a ring about the corpse of Caesar,

And let me show you him that made the will.

Shall I descend? and will you give me leave?

He fingers the blood-soaked robe and possibly lets them who "press" near touch it too:

- Look, in this place ran Cassius' dagger through:

See what a rent the envious Casca made:

Through this the well-beloved Brutus stabb'd ...

And then Mark Antony invites his countrymen to weep, a physical response that echoes Caesar's shedding of blood. By this time, they are ready to tear conspirators "to pieces" in the street. When one says, "Methinks there is much reason in [Mark Antony's] sayings," the use of the word "reason" is heavy with dramatic irony.

Mark Antony knows that his manipulation of the people is "mischief." There is really no dispute in the play that Brutus' way is morally better. At the very end, with Brutus dead, Mark Antony praises him as "the noblest Roman of them all." What makes Brutus great is his "general honest thought" and concern for the "common good to all."

The question Shakespeare raises is whether those who openly and candidly promote the common good can possibly prevail in public affairs. I suspect his answer is No. In real life, Caesar led the "populares" (populists) in the Senate, and Brutus belonged to the "optimates" (elitists). The populares appealed to the lower classes with grain subsidies and by limiting slavery, which undercut freemen's wages. In the play, the populares are wicked (after power rather than the public good), and the optimates are doomed men of virtue. That would make the play deeply conservative.

Shakespeare does not seem to consider a democratic interpretation: the people act badly in the play because they have no part in the crucial decision to kill Caesar but are merely asked to render judgment after the fact. Brutus is not simply virtuous but also cold and peremptory, reserving decisions to himself and expecting others to follow his "reasons." Brutus and Mark Antony are not the only two possible models of a politician in a republic: we can hope for empathy and modesty along with virtue. To describe that third course would have made Julius Caesar a worse tragedy, and less accurate as history, but it would have opened democratic possibilities.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:57 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 16, 2010

a critical review from the left

Alan Singer has written a strong and (in its own way) valid critical review of my recent book with Jim Youniss, Engaging Young People in Civic Life. Singer begins:

Former Congressional Representative Lee Hamilton, director of the Center on Congress at Indiana University, makes the purpose of this book clear in the preface. Civic education means moderated discussions in classrooms, encouraging participation in student government, preparing students to volunteer in their communities and enlist in the armed forces, and promoting participation in electoral politics. Civic engagement, as represented in this book, is polite. Unstated, but clear from its absence in the preface and throughout the text, it does not mean passion, and it does not mean questioning authority, challenging social inequality, and organizing protests against government policies.

The Civil Rights Movement is briefly mentioned on page 7 and Martin Luther King, Jr. on page 273. NOW, abortion rights, the labor movement, student rights campaigns, community control, and anti-Vietnam war and anti-draft protests are never mentioned. It is hard to believe, but in a book that claims to explore engaging young people in civic life, the movements that successfully engaged them when I was a teenage activist in the 1960s are completely ignored. That is because this book, sponsored by the Carnegie Corporation as part of its promotion of democracy in the United States, is not about civic engagement at all. It is about service-learning, electoral politics, and assimilating young people into the mainstream political culture.

There is definitely some truth to this. I'm pretty pro-regime. I don't like a lot of current policies and leaders, but I think the system is valuable, fragile, and liable to get worse if we don't care for it. I don't presume by the way, that all my co-authors would share that position; some are more radical. It does seem to me that preserving a system counts as "civic engagement," so I can't accept Singer's claim that we're "not about civic engagement at all." We address several varieties of it, but we don't define it as left-radicalism.

A major goal of the book is to benefit young people by giving them positive roles in their communities. We summarize research showing that such opportunities lead to better lives for the young people who participate. Although I also defend their right to protest and criticize, contributing to their communities pays off for them best--and that is a valuable outcome.

Singer writes:

- Young people have played major roles in transformative social movements throughout the 20th century and the first decade of the new century. In the United States, they were at the center of the civil rights campaign in Birmingham, Alabama, and bravely desegregated schools in the face of hostile mobs. In Soweto, South Africa, a student strike precipitated the campaign

that brought down the apartheid regime. In the 1960s and early 1990s high school and college students were major participants in mass anti-war movements and protests that helped to bring down the Soviet Union. In Europe and the United States immigrant rights campaigns have mobilized young people. There is much to report, if this is what you believe is important.

This is all true, but four caveats apply. First, the valuable outcomes of such participation were the social changes they achieved. For instance, young people played an important role in overturning Jim Crow in the American South, and that was a great achievement. But it didn't benefit them directly. Doug McAdam shows in Freedom Summer that the elite, predominantly white college student participants who went to Mississippi in 1964 were worse off than a comparison group in terms of their happiness, tangible welfare, and satisfaction in the 1980s. They paid a steep price for their activism. Their sacrifice was commendable, but our book is mostly about something else: helping disadvantaged young people to do better in life.

Second, the outcomes of youth political participation are not inevitably good. European fascism had a strong youth component. The American Civil Rights movement had distinguished elders. If you want to change the world for the better, the key questions are: What kind of change is desirable? And how can we get it? Whether and how youth should participate is a subsidiary issue.

Third, student activism was relatively rare even at the height of what we call "the sixties." In 1968, according to the HERI College Freshmen Survey, just 29.9% of first-year college students frequently talked about politics. This was during a year of assassinations, a momentous presidential election, the draft, riots, and war. In 1970, 3.1% of college freshmen considered their views "far left." Another 33.5% considered themselves liberals, leaving the majority as moderate, conservative, or unwilling to say.

Finally, imitating the radical movements of the 1960s might be welcome, but it isn't what most contemporary young people seem to want. If your commitment is not to particular social outcomes but to authentic youth voice, you have to listen to their priorities. Of course, today's young people are diverse and disagree among themselves, but the proportion who want to move the country in a radically leftward direction is small. For example, in many of the programs that encourage young urban students of color to choose their own issue for activism, the stance they choose is basically defensive and--in a Burkean sense--conservative. They fight against school closings, privatization, and budget cuts. In other words, they seek to preserve the status quo. That may not be anyone's favorite kind of civic engagement (including theirs), but it surely counts.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:54 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 15, 2010

what was Rawls doing?

John Rawls was the most influential recent academic political philosopher in the English-speaking world, or at least the most influential academic who defended liberal views. If you take him at face value, he is a very abstract kind of thinker. In fact, he says in section 3 of A Theory of Justice:

- My aim is to present a conception of justice which generalizes and carries to a higher level of abstraction the familiar theory of the social contract as found, say, in Locke, Rousseau, and Kant. In order to do this we are not to think of the original social contract as one to enter a particular society or to set up a particular form of government. Rather, the guiding idea is that the principles of justice for the basic structure of society are the object of the original agreement.

In a famous methodological move, he defines the "original position" as one in which persons are ignorant of all morally irrelevant facts so that each cannot "tailor principles to the circumstances of [his or her] own case." By making us ignorant of most empirical facts about ourselves, Rawls makes his theory seem more abstract than even Kant's.

As Rawls works out the actual framework of justice, it turns out that the government should do certain things and not others. Parties to the original contract would want there to be "roughly equal prospects of culture and achievement for everyone similarly motivated and endowed. The expectations of those with the same abilities and aspirations should be not be affected by their social class." To achieve this outcome, the government should fund education and channel educational resources to the least advantaged. I presume it should also regulate employment contracts to prevent discrimination, thus enacting the principle of "careers open to talents." But the government should not be in charge of child-rearing, even though families affect people's capacities and motivations. ("Even the willingness to make an effort, to try, and so to be deserving in the ordinary sense is itself dependent upon happy family and social circumstances.") The state should compensate people from unhappy families, but should not take over the family's traditional function.

Why not? One answer might be that Rawls was insufficiently radical and consistent. He arbitrarily excluded the family from his program of reform because of prejudice. I have a different view than this--more favorable to Rawls' conclusions but less supportive of his methods.

I don't believe that his reasoning was nearly as abstract as he claimed. Instead, I think he was a reader of newspapers and an observer of life in America, ca. 1945-1975. He observed that the actual government did a pretty good job of providing universal education but could still improve the equality of educational opportunity. The government policed employment contracts increasingly well to prevent racial and gender discrimination, albeit with room for improvement. But the government didn't do child-rearing well. (The foster care system was only an emergency response that, in any case, relied on private volunteers.) Rawls derived from the immediate past and present some principles for further reform.

That interpretation makes Rawls a good thinker, sensible and helpful, but not quite the kind of thinker he believed himself to be. In my view, he was less like Kant (elucidating the universal Kingdom of Ends from the perspective of pure reason) and more like Franklin Roosevelt, defending the course of the New Deal and Great Society in relatively general and idealistic terms. Or he was like John Dewey, critically observing reality from an immanent perspective. The reason this distinction matters is methodological. As we go forward from Rawls, I think we need more social experimentation and reflection on it, not better abstract reasoning about the social contract.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:49 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 14, 2010

AmericaSpeaks national discussion of the budget and the economy

AmericaSpeaks, a group that promotes public deliberations, will organize a national discussion about the budget on June 26, 2010. Americans will meet in large groups in up to 20 different cities, and also in online discussions and smaller community conversations. All the discussions will be linked, which is a new frontier in public deliberation.

The topic is of fundamental importance, because we cannot avoid deep decline as a nation unless we make difficult choices regarding the budget. Our political leaders and institutions are plainly incapable of doing the hard things, like cutting entitlements or raising taxes. And the public seems to want them to do nothing painful. As a board member of AmericaSpeaks, I will vouch for the neutrality and high-quality of their background materials and facilitation. This national discussion should yield truly thoughtful, informed public opinion and public will.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:45 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 13, 2010

the shame of our prisons

I've been reading the report of the Commission on Safety and Abuse in America's Prisons (PDF). It tells basically a tragic and horrifying story, although it also cites some individual prisons and even whole states that have achieved dramatically better outcomes than others in terms of reducing prison violence and rape as well as recidivism.

One premise is the gigantic scale of our prison industry. "The daily count of prisoners in the United States has surpassed 2.2 million. Over the course of a year, 13.5 million people spend time in jail or prison, and 95 percent of them eventually return to our communities. Approximately 750,000 men and women work in U.S. correctional facilities as line officers or other staff." (p. 11) These numbers have increased steadily even when crime rates have fallen.

The incarcerated population is highly needy. To mention just one challenge, "At least 300,000 to 400,000 prisoners have a serious mental illness--a number three times the population of state mental hospitals nationwide" (p. 38).

All prisoners are somewhat isolated from society; that is the point. But policies sharpen their isolation in ways that prevent prisoners from successfully re-entering their families and communities later. For example, they are discouraged from talking to family members. The "average cost of a 15-minute in-state long-distance collect call placed from a correctional facility" is high almost everywhere. In Washington State, it is $17.77. "In Texas ... the very ability to make calls is severely restricted: 'Offenders who demonstrate good behavior can earn one five minute call every 90 days'” (p. 36).

Within prisons, a large subclass of inmates is isolated from the rest, indeed, deprived of all human contact by being placed in solitary confinement. On one day in 2000, "approximately 80,000 people were reported to be confined in segregation units."

Some use of solitary confinement is inevitable, but it is growing much faster than the prison population (p. 52-3). Some prisoners are held without human contact for many months or as long as nine years, and often as disproportionate punishments. "For example, a young prisoner caught with 17 packs of Newport cigarettes--contraband in the nonsmoking jail--was given 15 days in solitary confinement for each pack of cigarettes, more than eight months altogether" (p. 54).

Many prisoners are held in solitary confinement because they are regarded as too dangerous to be managed within a prison--and then released into society. "People who were released directly from segregation had a much higher rate of recidivism than individuals who spent some time in the normal prison setting before returning to the community: 64 percent compared with 41 percent." (p 55).

Posted by peterlevine at 9:35 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 11, 2010

fictional stories about collective agency

(In DC briefly, for a class at Georgetown Law School) Are there fictional stories--novels, movies, long poems, or works in other formats--that depict networks or other large groups of people who improve the world?

There are fictions about individuals improving the world: heroic teachers making their inner-city kids into academic stars, whistle-blowers overthrowing evil corporations, and good cops achieving justice in bad cities.

There are true stories about networks and associations that improve the world, like the excellent historical narratives of the abolitionist movement, the American Civil Rights Movement, and the Indian independence struggle. (The scholarly studies do not attribute excessive importance or originality to individual leaders, Martin Luther King or Gandhi. When the good side wins, it is always because of the whole network.)

There are fictions about groups of people in difficult and unjust circumstances. For example, The Wire is a brilliant depiction of a whole network of people trapped in a heartless system. It is realistic, but it is not a story of agency. Characters in The Wire who try to improve the world fail.

There could be realistic fictions about groups of people who succeed in changing institutions and systems. But are there any? Does the failure to envision such success tell us anything about our art, or our society?

Posted by peterlevine at 7:21 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 9, 2010

classroom practice from an ethical perspective

(Madison, WI) I am here for one of a series of meetings organized by University of Wisconsin Professor Diana Hess and funded by the Spencer Foundation. Diana and her colleagues have assembled remarkable empirical data about high school students and their social studies classes. From their longitudinal surveys--which follow the students into their twenties--they can draw inferences about the effects of various school experiences. Their elaborate interviews of students and teachers and their classroom observation notes help to explain the quantitative data and also provide numerous interesting anecdotes. The interviews, in particular, draw attention to dilemmas. Should you deliberate issues in a classroom that may be offensive to some students? Should you allow students to deliberate issues that should be settled? Should a teacher disclose his or her personal views?

The empirical data are relevant to these questions. For instance, it might turn out that teachers' disclosing their opinions affects students' opinions. But the data cannot settle these questions, which also involve value judgments about both means and ends. The appropriate ends, in particular, are by no means clear.

Therefore, Diana and her colleagues have assembled professional philosophers to discuss the empirical data with the researchers. There are actually three kinds of background in the room. Almost all the participants have personal experience as teachers. The quantitative data is more general and systematic but less rich than personal experience. And everyone has some level of philosophical training or interest. This seems to me a model for how to think about thorny issues.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:35 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 8, 2010

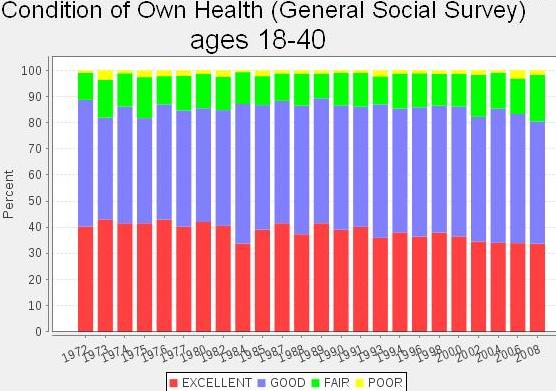

graphs of the day: health spending, health outcomes

The total proportion of our economy devoted to health care has increased from 7 percent in 1972 to 16 percent in 2006:

Yet the proportion of Americans who consider their own health to be "excellent" is slightly lower than it was in 1972:

You'd think the reason might be an aging population, but no dice. When you look at only people between the ages of 18 and 40, their self-reported health situation actually declines:

Posted by peterlevine at 9:45 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 7, 2010

participatory budgeting in Chicago

Participatory budgeting started in Brazil, when residents of poor urban neighborhoods were given control over capital budgets. They now meet in large groups and decide how to spend government funds deliberatively. The outcomes of participatory budgeting in Brazil include better priorities, greater public trust in government, and much less corruption. The last benefit might seem surprising, but it appears that when people allocate public money, they will not tolerate its being wasted.

Participatory budgeting is one of many important innovations in governance that have originated overseas and that should be imported to the US. Now is a time of great creativity in democratic governance, with the US generally lagging behind. We suffer from too limited a sense of the options and possibilities.

I believe there has been some participatory budgeting in California cities. And now Chicago Alderman Joe Moore announces:

As a Chicago alderman, I have embarked on an innovative alternative to the old style of decision-making. In an experiment in democracy, transparent governance and economic reform, I'm letting the residents of the 49th Ward in the Rogers Park and Edgewater communities decide how to spend my entire discretionary capital budget of more than $1.3 million.

Known as "participatory budgeting," this form of democracy is being used worldwide, from Brazil to the United Kingdom and Canada. It lets the community decide how to spend part of a government budget, through a series of meetings and ultimately a final, binding vote.

Though I'm the first elected official in the U.S. to implement participatory budgeting, it's not a whole lot different than the old New England town meetings in which residents would gather to vote directly on the spending decisions of their town.

Residents in my ward have met for the past year — developing a rule book for the process, gathering project ideas from their neighbors and researching and budgeting project ideas. These range from public art to street resurfacing and police cameras to bike paths. The residents then pitched their proposals to their neighbors at a series of neighborhood "assemblies" held throughout the ward.

The process will culminate in an election on April 10, in which all 49th Ward residents 16 and older, regardless of citizenship or voter registration status, are invited to gather at a local high school to vote for up to eight projects, one vote per project. This process is binding. The projects that win the most votes will be funded up to $1.3 million.

I am strongly opposed to discretionary budgets for legislators. That's just a way for them to buy reelection with public funds. But the fact that Alderman Moore has such a budget is not his fault, and he is using it for an excellent experiment.

Posted by peterlevine at 3:17 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 6, 2010

philosophers dispensing advice

Yesterday, for fun, I posted a clip of the philosopher Jonathan Dancy on the Late Late Show. His interview raises an interesting and serious question. Asked whether philosophers should dispense moral advice, Dancy says: No. I would agree with that, for reasons stated below. But Dancy goes further and suggests that philosophers shouldn't address substantive moral issues at all. He implies that people's ethical judgments are already in pretty good shape. A philosopher's job is to understand what kind of thing an ethical judgment is. In other words, moral philosophy is meta-ethics.

That is a controversial claim. John Rawls, Peter Singer, Robert Nozick, Judith Jarvis Thomson, and many other modern philosophers have advanced and defended challenging theses about morality. Since the great renaissance of ethics in the English-speaking world (1965-1975), its ambitions have diminished, I think, and a distinction has arisen between ethics (which is very "meta") and applied ethics (which is mostly about a given topic area, and not very philosophical). This split seems a harmful development, because the best moral philosophy is methodologically innovative and challenging and also addresses real issues.

Why shouldn't philosophers dispense advice? Because what one needs to advise people well is not only correct general views (which, in any case, many laypeople hold), but also good motivations, reliability and attention, fine interpretative skills, knowledge of the topic, judgment born of experience, and communication ability (meaning not only clarity but also tact). There is no reason to think that members of your local philosophy department are above average on all these dimensions.

But correct general views are valuable, and philosophers offer proposals that enrich other people's moral thinking. You wouldn't ask John Rawls to run a governmental program or even to advise on specific policies, but your thinking about policies may be better because you have read Rawls. It so happens that he held some interesting ideas about meta-ethics, but those were merely complementary to his core views, which were substantive.

I'm afraid I detect a general withdrawal from offering and defending moral positions in the academy. Humanists like to "problematize" instead of proposing answers. Social scientists are heavily positivist, regarding facts as given and values as arbitrary and subjective (thus not part of their work). If moral philosophers begin to consider the offering of moral positions as beyond their professional competence, there's virtually no one left to do it.

Posted by peterlevine at 2:00 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 5, 2010

a philosopher hits the big time

I'm an adherent of a very small and obscure philosophical school called "particularism." (Of course, because I'm an academic, I have to have my own special flavor of it.) The best known particularist is Jonathan Dancy, whom I only met once but who nicely reviewed a book manuscript of mine. And his work has had a big influence on me, even though I come at things from a different angle. Anyway, unbelievable as it may seem, here he is explaining particularism on Craig Furgeson's "Late Late Show" on CBS:

I've never seen his show, but this Furgeson guy strikes me as pretty smart. And Dancy does a credible job in a terrifying situation. It turns out he's the actress Claire Danes' father-in-law. That relationship--rather than the arguments in "Are Basic Moral Facts both Contingent and A Priori?" (2008)--may be the reason for Dancy's new TV career. Whatever the reason, long may it prosper.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:11 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 2, 2010

students are not customers

Colleges and universities commonly talk about serving "customers." For example, Tufts University officially promotes a "Customer Focus" for its employees, which means: "Pay attention to and focus on customer satisfaction • Develop effective and appropriate relationships with customers • Anticipate and meet the needs of both internal and external customers."

I understand and even endorse the motivations here. Students and others pay us lots of money, and we should try treat them respectfully, efficiently, and in a way that satisfies them. We can draw lessons from consumer-oriented businesses. For example, we mustn't make students wait on long lines for no apparent reason, as was traditional in higher education even 20 years ago.

But we aren't actually a business, and we don't have customers. Our main products are education and new knowledge. That means that the people we "serve" include students, readers (and other users of our research), and collaborators in research or educational projects. Students and readers are not customers, because the customer is always right. His or her preferences should be met, if possible. In contrast, our job is to challenge, guide, and assess, whether the student or reader wants that or not.

Further, a customer is basically passive. Consumers actively choose what they want, but the company produces it for them. In contrast, our students, readers, and community partners actively co-produce knowledge with us. They are colleagues rather than customers. We need to teach them to see themselves that way (not as people who have purchased services).

We also have obligations that are not to any individuals but to abstractions, like truth and fairness.

Finally, the implication that we are providing an expensive customer service leads not just Tufts but the whole sector (including public institutions) to spend lavishly on things like residences, student activities, and support services. Harvard, for example, employs 5,102 "administrative and professional" staff (excluding clerical and technical workers and those in "service and trades"). Harvard has 112 full-time professional and administrative workers in its athletics department alone. This compares to 911 tenured faculty (or 2,163 total faculty). Harvard students no longer have personal servants assigned to them, as their predecessors did in the Gilded Age. But they have a similar number of service workers at their beck and call.

Meanwhile, the cost of higher education has far outpaced inflation for several decades, and four-year colleges have ceased growing even as the young-adult population expands. I am not sure that their core educational mission benefits from all this spending, but problems of access are becoming acute.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:49 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 1, 2010

joining the Tufts Roundtable

As of yesterday, all my blog posts are being syndicated on the Tufts Roundtable. That's a student-run organization that started with a regular magazine devoted to policy issues. The magazine deliberately mixes liberal and conservative (and other) articles, all highly substantive. It still appears regularly but has now been joined by blogs, radio- and video-casts, and a whole social network. The Roundtable is the Huffington Post of Tufts, only with better quality.

So I'm pleased to be appearing there by automatic RSS feed. And for those who are encountering this blog for the first time on the Roundtable, let me say: Hi. I'm a scholar at Tufts, I direct CIRCLE in the Tisch College of Citizenship and Public Service. I blog every work day (except last Monday, when my site was down) about civic engagement, ethics and moral philosophy, and some cultural and personal topics that just happen to interest me.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:00 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack