« July 2009 | Main | September 2009 »

August 31, 2009

what the public option means about our politics

The best reason to create a public health insurance option is to increase competition in the health insurance market and thereby lower premiums. No one can know how much money a public option would save, but the idea seems worth trying as an efficiency measure.

It is being treated as much more than that--as the central battle of the summer and perhaps of the whole 111th Congress. Some liberals (an explicit example is Paul Krugman) want to show that assertive governments can do good--thereby debunking modern conservatism, which holds that governments are the problem. Passing a public option would demonstrate that a ruling majority in America today supports activist government; the success of the new policy would then increase support for such activism. As Mark Schmitt observes, the origin of the public option was not research into which policy would cut costs, but rather a political strategy to get a victory for expansionist liberalism.

For that very reason, conservatives want to defeat the proposal. Defeat would demonstrate that there is no pro-government ruling majority in America today; it would also allow opponents to argue against the evils of the public plan without the risk that it might work in practice.

This kind of proxy battle is common today. For example, charter schools are promoted by libertarians, who want to demonstrate that choice can improve quality even in an area traditionally run by the state, and by moderate liberals, who want to show that the public sector can innovate and therefore doesn't deserve to be cut. Charter schools are opposed by some traditional liberals who think that market-type competition is overrated and who want to draw the line at the schoolhouse. The decision whether to turn a given school into a charter thus becomes an ideological proxy battle rather than a rather complex, nuanced, fundamentally local question about which governance structure would work best in each situation. (See my analysis here.)

There are advantages to ideological politics. We must simplify by applying broad principles, or else the complexity, variety, and nuance of the world is overwhelming and we cannot act at all. Voter turnout rises when there is more ideological conflict because it is easier to engage when the lines are sharply and simply drawn. Ideological strategists, such as the libertarians of Victorian England and the activist liberals of the New Deal, have sometimes achieved great things.

But the drawbacks of ideological politics are obvious: oversimplification, suppression of worthy alternatives, manipulation of voters who aren't attuned to the ideological game, and a tendency to confuse means with ends. We see these problems in today's health care debate. The true goal for progressives is to provide all Americans with affordable health insurance. There are crucial provisions in the main Congressional bills for that purpose--notably, subsidies for low-income Americans and regulations to protect people who have pre-existing conditions. The details of these provisions are essential. Who is eligible for how much financial support are the most important questions for poor people. They are not, however, the focus of the great national debate--for two reasons. First, poor people are not organized or influential. Second, subsidies are not an ideological proxy issue. We already subsidize health care--it's unexciting (but very important) to propose spending more.

The public option should be a means (a mechanism to cut costs and therefore make it easier to insure everyone), but it is becoming the end because of its symbolic role in ideological politics.

Meanwhile, liberals don't seem interested in the potential of private co-ops, if appropriately designed and funded. That's because co-ops have been portrayed simply as a compromise between liberals and conservatives, and therefore as a disappointing outcome for those--on both sides--who want an ideological "win."

I suspect that the health care debate is less engaging for average Americans than it should be because it has turned into an ideological proxy debate that makes most sense to the "base" on both sides. By the way, the conservative ideological base is usually about twice as big as the liberal ideological base--26% called themselves conservatives versus 15% who identified as liberals in the 2004 American National Election Survey.

I noted above that ideologies can encourage participation by providing comprehensive worldviews that make decisions easier. But only certain kinds of ideologies work for that purpose. A vital ideology needs an impressive story arc, beloved and talented current leaders, moving examples, strong networks and organized backers, opportunities for grassroots engagement, and a coherent theory. New Deal liberalism had all those, at its peak. Paul Krugman's ambition is to resurrect statist liberalism as a movement. Maybe that's possible, but it certainly hasn't happened yet. Thus I am not at all surprised that most people feel left out of the ideological proxy war that is taking place among political elites and strong partisans. I am also not surprised that conservatives are winning the health care debate--it is a proxy battle, and they have more true believers. If it could be about how to provide the best possible health care for all Americans, it would be a different story.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:32 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 21, 2009

The Anachronist, chapter 1

We are going on vacation for a week, and I will be offline until August 31. Meanwhile, chapter 1 of a novel entitled The Anachronist is pasted below. I have written the novel through to the end (working on it since 2001), but some parts still need development.

The Argument:

A woman is bound to the stake to be burned:

No hope of using the secrets she’s learned.

A sagacious doctor awaits his fate,

Captive in the Tower behind Traitor’s Gate.

His student could strike to make justice prevail.

Righteous he is, but his judgment may fail.

Over the sea comes a painter who sought—

Not the dark cellar in which he is caught.

In the midst of these four, a lady is torn.

She must choose just one, leave the rest forlorn.

Time’s arrow flies; look where it lies.

A woman stands to her waist in a mound of logs and tightly bundled furze kindling. The logs beneath her feet cut into her bare soles. A rope winds around her body from her thighs to a triple knot at her chest. The stray hairs on the knot’s surface shake in the wind. She thinks: One watches small, harmless things like this every day of one’s life. If I were a child, I would play with this rope, pull its strands apart, drag it behind me like a tail.

She feels a great oak beam pressing through her linen smock. To her left, she sees seated clergymen and dignitaries. One is a portly, bearded, red-faced gentleman who wears a heavy gold chain over his furs. She knows him well as Sir Thomas Lucy, Justice of the Peace and Member of Parliament. Sir Thomas affects the same disappointed schoolmaster’s expression that he tried to maintain during her interrogations, but all traces of his eagerness and anxiety have been replaced by barely concealed satisfaction. His fat hands, which twitched and pointed constantly in the cell, now lie relaxed in his lap; his rings glitter in the wan light.

She is bound too tightly to turn her head around. However, decades of grueling daily practice have made her an expert at recalling visual memories as if they had been captured in paint. With her eyes shut, she can clearly picture what must appear behind her. The square little church of St. Mary Magdalen stands before the city’s main northern gate. To its left, also just outside the city walls, must rise the crenellated profile of Balliol College. She smells the smoke from a college chimney along with leaf mold and sewage. The town’s other spires, turrets, and flags surely make a pleasant pattern under the scuttling clouds and the low winter sun, which shines directly behind her. And far to the right is Oxford’s castle on its ancient motte, where she was held screaming and weeping for the past eleven pitch-black nights.

She chooses not to look rightward toward the constable, who must be busy with his flints and tinder: she hears their scratching sound. Before her time in the castle, she would have begged this man’s mercy and expected him at least to pity her. She wonders why she was ever prone to trust. As a little girl, didn’t she see her own mother and father hanging by their necks in a long row of bodies, while the crows circled and cawed over Antwerp and the papist army set the thatch to fire? Someone deliberately tied ropes around their necks and dropped them to choke. If they begged for their lives, no one listened. All men are sinners; many do worse than this fellow who will soon execute her. And was not she, Anna Clauwaert, also born into mortal sin?

A crowd has gathered to watch her burn. From her vantage point on an earth embankment, these people look like stocky bundles, well wrapped against the late October chill. They are spaced widely enough that she can see plenty of churned mud, horse droppings, and patchy grass among them: a rich, dark background for their red and orange woolen cloaks and the bleached hats of the women. She decides that once the fire is lit, she should try to inhale as much smoke as she can, in the hopes of losing consciousness before her skin begins to blister.

Most of the onlookers are common townspeople or country folk with big noses and chins and squinty eyes. There are a few gentlemen in view, recognizable by their swords. For example, some twenty paces away, a tall fellow stands with his back to her, facing his own long shadow. He wears a tight velvet jacket and a broad, feathered cap over his red hair. She can see his fine, strong legs through his hose.

“Lord God,” she thinks in her native Dutch, “I confess that I am rotten with lust and fear and every other contemptible sin. Your will is unalterable and just; if the earthly flames that will soon scorch my skin and lungs”—here she must pause a moment—“if those flames are merely a foretaste of endless hellfire, Thy will be done.”

This prayer is rehearsed; she has honed it for days and even said it aloud a dozen times on her knees in her cell. This time, as she recites it silently, the rope chafes her arms and a silent wind whips the parts of her smock that are free to move. She continues inwardly: “But I do not know, Lord—truly I do not know why I am being persecuted, nor what has befallen my master, Dr. Edmund Burby. I pray only that I may be granted a chance to find the truth so that I may be Your instrument of justice before I die.”

Beyond the redheaded gentleman with the sword, four small boys are playing with a leather ball. One has just hurled it at another as hard as he can, but his target has ducked and the others are laughing. Another twenty paces behind the boys, two women stand huddled together with their faces almost completely obscured by baggy white muffin caps and woolen scarves. Anna thinks of a Latin phrase that her master once showed her in an old manuscript. They could not translate or parse it, but it was said to have some efficacy. She knows that she should shun such texts as Satan’s own work, especially on the day that she will face her Maker in judgment. She does not allow herself to say the magical phrase aloud, but she does think it, letting the strange syllables sound in her head one at a time.

Her eye wanders further along the wide thoroughfare of St. Giles. In the distance, that road passes through a rusticated arch that is built into a peaked-roof building with leaded windows. This is the Bocardo Prison, attached to the old church of St. Michael. It looks like a barbican, but it stands alone, no wall connecting it to the rest of the city’s fortifications. Between Anna and the Bocardo, St. Giles Street is lined by modest houses, kitchen gardens and open orchards that dissolve into common fields, and a few inns. Outside a public house on the right whose sign names it “The Town,” a knot of men stand holding their pewter tankards and looking in her direction. They want to watch her face and hair catch fire like a torch—without leaving their ales inside the inn. One man strikes a flint to light his clay pipe; she notices the sparks.

It seems infinitely sad that she will never again see whitewashed walls, rickety fences, or ridges of dried mud on a road. “Our Father,” she says to herself, still in Dutch, “You who are in heaven, your name ...” She is now looking at objects remarkably far away, she realizes. The pub is a half-timbered and thatched building. There is a small window just past the door, but the leaded glass is dull and opaque, save for a few glinting highlights. She focuses on a little patch of yellow wall with a sloping red roof. At the corner, a horse has its nose in a bucket. Anna’s eye takes in the gloss of its coat, its ribs, its skinny hind legs, and its dirty white tail.

Which is around the corner of the pub. She should not be able to see this tail; only the horse’s head should be visible from her perspective, and it should be very small. Objects shrink in proportion to their distance from the viewer, but it is as if she has moved so close to the surface of this scene that she can observe distant things close up—and now even see around corners. She thinks of looking back toward herself, but she is afraid of what she might find. Instead, she looks further along the side street, the sun now to her right.

The gardens grow larger as she hastens along; soon there is a wide orchard on both sides of the road. The bare branches of bigger trees form a shifting lattice studded with silent crows; and then she sees a stile ahead. “City of Oxford Common” says the painted lettering on a crude wooden sign. She is a mile away from the pyre at St. Mary Magdalen Church, heading toward the River Thames.

This part of the Common is called Port Meadow; it is a rolling expanse of grass and puddles that she crosses as she looks toward the misty river. Any freeman of Oxford may pasture his animals here. Anna passes two sack-of-bones cows, one muddy sheep, and a donkey. Skinny boys collect manure to burn before a lean-to that they have constructed under a tree. In the distance, a dissolved monastery is slipping into ruin, its stones stolen by townspeople for their houses. To Anna’s Flemish mind, Port Meadow has always seemed a waste. If the Corporation of Oxford built a dyke along the river bank, put a drainage canal through the middle of the field, and planted hedgerows, this land could handle ten times as many animals.

But she is not thinking about enclosures today—nor does she fear the robbers who lurk on common land. She knows where she must go: the river is her path. She reaches it and moves downstream over placid water that seems to steam a little near its reedy margins. A couple of mallards leave a v-shaped wake as they paddle across, and a peasant in mismatched leggings fishes from a flat boat. She passes right behind the Oxford Castle, although she avoids looking at that place of nightmares. The Thames is narrow here and twists sharply: just a stream with green, reedy water and steep banks. A man sits in the saddle as his horse drinks, standing in water up to its knees. She passes a foot away from the fellow and his animal, undetected.

As the buildings cluster together more tightly—she is moving into the heart of Oxford Town—the Thames merges with a tributary and changes its character. It is wider and faster here, its banks are more sharply defined, and rowboats dot its surface. A watermill churns busily, tended by bustling women while others lay sheets out to bleach. She recalls something that her tutor, Dr. Burby, once told her. He had been playing with his retorts, pipes, and beakers, pouring liquids together and showing her how they bubbled and foamed. “Look,” he said—speaking the Latin that was required at all times in the college—“how unlike substances, when they meet, become more alike. Hot and cold combine to make a lukewarm liquid. Base and precious metals mix in nature and then require much labor and intelligence to separate, even temporarily. A sharp vinegar and this salty soda, after they have foamed together, will create something flat and bland and lose their distinct characters. Life is the clash of differences; death is sameness.”

Anna never understands this kind of talk, nor why her master insists on playing with alchemists’ tools. Men are burned for alchemy. Dr. Edmund Burby is supposed to be a historian, writing a great vindication of the Reformed Church that will begin with the Acts of the Apostles and end with the providential accession of the Protestant Queen Elizabeth to the English throne. This work will confound the Pope himself with its pious learning. It was to study under such a scholar that Anna dressed herself as a boy, forged a letter of introduction, and traveled perilously from Flushing to Oxford at age sixteen. The doctrines that he persists in telling her about chemicals and metals are at best idle; at worst, they are lies. The world’s story is not about differences turning to sameness. On the contrary, the true and original church has split into countless sects, most of them shocking heresies. Meanwhile, people have invented a Babel of languages with which to tell their fictions. God is One; sinners generate faction and strife because of their selfish wills.

She is out of Oxford now; the river is still wider, having merged with the Cherwell. The stately tower of Magdalen College passes behind her. Along the banks she sees enclosed pastures, dotted with sheep; open fields, tilled in long rows; and thick woods. She is intent on maintaining her concentration, her continuity of vision or memory or imagination—for fear that a lapse will put her back on the pyre. But she finds that she can move considerably faster than a pedestrian. She sweeps above the river like a gull on its way to the sea. From her high perspective, the woods look surprisingly large and undisturbed. This realm is still a great forest, she thinks, having seen it before only from a roadside or a boat.

Now here comes the ragged edge of the clouds that had covered Oxford. This band of gray is moving toward London. It suddenly occurs to Anna that “weather” is not a change in the state of affairs in a given place. “Weather” is the movement of great atmospheric masses across the surface of the globe. If people exchanged frequent and quick messages about the state of the weather wherever they happened to be, wouldn’t it be possible to predict the coming of rain or high winds? But how could those messages move faster than the weather itself? Maybe bonfire signals would work, like the ones that followed the course of the Spanish Armada. Could men be paid to send daily weather messages by bonfire?

Another question comes to her: Why does the weather constantly swirl? Why don’t the masses of clouds come to a stop, like the milk in a churn when a farm girl lets her paddle drop at the sound of footsteps in the barn? It must be God who keeps churning the atmosphere, actively intervening to keep the world in motion—to fill our sails, turn our windmills, and bring us rain. If God were an absent creator, nature would quickly run down; clouds would dissipate; everything would become a still and even fog, deadly to crops.

The Thames turns in huge ox bows, consuming many more miles than it needs to reach London on its descent to the sea. At one turn, Anna notices an encampment of beggars. She has seen many like them recently, even in town. The harvest is in and winter is almost upon them; but the harvest was bad and hunger already bites. To travel without a license is a crime. These people should till land, serve a master, or ply a trade. They should not be gleaning free berries, game, and firewood or—as she notices they have done—turning someone else’s soil for their vegetable garden. From a distance, they look picturesque, like figures in a miniature landscape from Anna’s homeland. But when she draws closer she sees that the little potbellied girl sits by the riverside, legs splayed, wrapped in rags, her bulging eyes staring emptily.

At Windsor, the massive round keep flies the Queen’s standard, and the people by the riverside are jauntily dressed in fashion. A very fat fellow with a big feather in his hat makes a deep bow as he tries to detain three housewives in farthingales. Then more thick woods, little towns, and another turn of the Thames reveals Hampton Court. Near this palace, liveried servants row long, gilded barges, and sailboats tack downstream with loads of vegetables.

Before London comes Westminster with its towerless Abbey, the long roof of Parliament House, and a grand marble staircase down to the river. Then a row of palaces, each with its own landing stage still streaming from the tidewater; and Saint Paul’s with its squat central tower, crowded by the spires of London’s other churches and the masts of docked ships. Windmills dot the hills further away from the river. People swarm the streets and landings near St. Paul’s like rats on rigging.

The Cathedral stands on Anna’s right-hand side even though she faces downstream. She is not very well acquainted with London, but she knows that St. Paul’s should be on her left; the right bank is another town altogether. Everything appears in mirror-image and must have been reversed since—when? Since the horse outside the pub in Oxford?

Anna considers that the mind does not see the world. The mind is located behind the eye, which is a reflective surface that mirrors the world. (Stare closely into someone’s retina and you will see yourself reflected there.) Thus the mind must be accustomed to reversing the image it observes on the back side of the eye. Moreover, the mind must be invisible, for no autopsy has ever found a being with its own little eye that watches the back of the retina from inside the head. Thoughts are incorporeal, and the mind or soul must be that bodiless substance that observes the physical image on the retina. But Anna is not looking with her eye; today, her mind directly observes the world, which therefore appears reversed. Or does she see it the right-way around for the first time in her life—maybe for the first time in history?

London Bridge looms with its grand half-timbered shops. The boats are as crowded here as cows at a Flemish cattle market; rowers struggle to separate their tangled banks of oars and one young man jumps from vessel to vessel with a live turkey while the owners shake their fists at him. Fish heads and other trash bob in the choppy water. As Anna nears the dank dripping arch of the bridge, she can see the floors of the shops and houses jutting over the water. Here the Thames forms boiling rapids.

Anna’s vision reemerges into the sunlight. To her right (although she still expects to find it on the left), is the Tower. Its most prominent feature is a tall, square, whitish building with crenellations and a turret at each corner. It is a very old-fashioned and grim keep, although its turrets have been topped with wooden domes like jaunty little hats. Between this white tower and the river is a massive fortress wall with a gate that is more than half submerged by the tide. There are pikes on top of the gate, and skulls on the pikes. Anna passes through the bars of the gate, up a steep, wet covered passage, and into the open bailey with its many fine buildings. She briefly notices a row of cages and the spotted coat of a pacing big cat. An uncaged bear sits chained to the base of a wall.

She works her way methodically along the four walls of the White Tower from the ground floor up, peering into each window. She finds dark rooms jammed with crates and bales, a kitchen with gleaming copperware, some kind of holding cell in which are packed a dozen standing prisoners, another cell with a poor bloodied fellow in the stocks, and several guardrooms well stocked with pikes, muskets, and cannon balls.

This evidence of military professionalism is a pleasant surprise. English troops are at war in Anna’s homeland, helping to liberate her nation from the murderous Spanish papists. She thanks God for their aid, but she wishes they could be more impressive on the battlefield. The whole English government often strikes Anna as a rickety affair, run by a few amateurs, funded out of the Queen’s own purse or on her personal credit, beset by traitors, vulnerable to invasion. The Pope has declared Elizabeth a usurping bastard and a heretic, calling on the faithful to assassinate her. Unknown thousands of English families are secretly loyal to Rome. Ireland is in open rebellion and plots are uncovered every year. But for a providential wind that blew up the Channel in ’88, Spanish ships would have landed thousands of ruthless, seasoned soldiers and Jesuit inquisitors on the beaches of England and the cause would have been lost.

This very tower is filled with conspirators. Some will be held here indefinitely; some will be released on the orders of the Privy Council. Some, by the Queen’s mercy, will go to the block to have their heads instantly axed off. But some of the Tower’s traitors will die in the following way. They will be placed face down in a cage that is pulled by horses through the rough streets of London while people run alongside and jeer. They will be hanged by the necks until desperately heaving for air. They will be cut down from the gallows, still alive, and stripped before the London mob. Their genitals will be sliced off, displayed before their faces, and then burned in a brazier. Their stomachs will be cut open at a place calculated not to cause immediate death, and their intestines will be drawn out of their bodies and added to the fire. Last, the executioner will chop them into bloody quarters.

As Anna reaches the third and fourth floors of the White Tower, she finds that many of the rooms are elaborately furnished. Either the genteel prisoners are permitted to live in comfort at their own expense (as Anna has heard), or else these chambers belong not to prisoners but to the governor and other royal retainers. One room is hung with Flemish tapestries of Diana and her hunt.

She recognizes Dr. Burby’s room immediately. In a corner chamber on the fifth floor, he has reproduced precisely the arrangement of objects that used to line the walls of his study at Balliol College: books laid flat on shelves, polished sea-turtle shells, antlers from numerous species that he has arranged in order of size, pendulum clocks, globes and celestial spheres, small antique marble busts, stuffed birds, a camera obscura, a lute, mirrors, retorts and beakers of blown glass, porcelain from the orient, a cabinet of dark wood carved to resemble a palace façade, a pot of rosemary (for remembrance), crude beads strung on leather, a Saxon inscription, an abacus and an astrolabe, a human skull, three prisms hung from the rafter that turn slowly in the air, a table covered with a Persian carpet, and a printed portrait of the Queen after Nicholas Hilliard. The whole chamber is rather gloomy; portions are concealed in inky black shadows.

Dr. Burby has not arranged these objects so carefully just to remind himself of his old life or to make himself comfortable in prison. Like Anna, he is a devotee of the Art of Memory. Every day, he visualizes some familiar scene, such as the view from his study window, the interior of his parish church, or the shelves that line his walls. He associates each familiar object with something that he is trying to memorize, whether the Saxon Kings of Wessex in order of their succession, the natural metals, or the vocabulary of Hebrew. When he runs out of real objects with which to associate these ideas, he invents extensions to his memories. For example, his parish church may develop an imaginary door, through which he can reach a cloister surrounded by chapels, each filled with monumental brasses that he can associate with Hebrew verbs. Or his study may extend for one hundred, or even one thousand, paces in his mind, instead of its actual ten.

By this method, Dr. Edmund Burby is able to memorize vast amounts of knowledge—although perhaps with less success than the Jesuit Matthew Ricci, who has used the Art of Memory to master Chinese speech and writing within months. The heathens are so astounded and bewitched by Ricci (or so an English agent in Macao reports), that there is great concern lest they convert by the millions to Romanism.

In any case, the Art of Memory is not merely a tool for absorbing facts or impressing pagans. An expert can visualize how one idea relates to another by mentally moving the corresponding objects in imaginary space. In that way, he can discover the occult patterns of the elements, the heavens, or the books of scripture.

Anna knows Dr. Burby’s chamber by heart, just as she knows the skyline of Oxford and the portraits in her college hall. She also knows the streets and canals of Bruges as if she had a map spread out before her—although she has deliberately added whole imaginary neighborhoods to that city to accommodate the ideas that she has memorized. She is the free mason of those fictitious quarters. But it was in the real Bruges, when she was only a child, that she began to cultivate her memory in order to teach herself Latin, Greek, and Hebrew. Lacking the strength to bear a sword or a musket against the papists who had murdered her parents, she decided instead to exercise her mind. She dreamed of learning new languages before Catholic missionaries could master them and convert more continents to idolatry. She longed to solve riddles of nature or history and thereby vindicate the reformed church and confound its enemies. It was the Art of Memory that took Anna to Oxford. She saw England as a New Jerusalem—a citadel of faith—and arrived there full of optimistic zeal; but she has since decided that Dr. Burby’s character epitomizes his whole rather frustrating nation. She finds him in equal measures able and distracted, energetic and complacent, competent and naïve.

Through the blown glass of the window, Anna’s vision alights on a polished brass candlestick, in which she notices movement. She has caught the reflection of an elbow, clad in velvet. Moving into the room, she sees that it is the elbow of an Italian man—to judge by the luster of the fabric, the bold purple stripe that runs from his shoulder to his cuff, his loosely flounced white collar, his mane of black curls, and his hat with its great plume. He sits at a desk, his back to the window, hunched over something that is illuminated by a candle. The flaming wick is concealed by the Italian’s raised hand, which glows translucently. As she moves even deeper into the dim room, she sees that the Italian is examining a book, which her master, seated at his left, also bends over. She recognizes Dr. Burby at once from his skullcap, the age-spots on the back of his neck, and the white bristles that are caught in a ray of light from outdoors.

The book that they are examining is large and wildly colorful, like a parrot that has flown into a smoking house. It has a wide green-and-gold border with a kind of script that Anna has never seen before. Within the border is an image, predominantly pink, red, and ivory but with many other sparkling colors spaced evenly. This area is divided into perhaps eight zones by architectural elements: walls, floors, and tents or pavilions. Anna’s eye begins near the bottom, where beneath brick arches, several small people are working around a great black pot. They are olive-skinned and wear bright clothing of several colors. In the clear, even light, they cast no shadows.

On a shelf near the pot, Anna can make out limes, bunches of an herb that might be coriander, onions, clusters of nuts, and a mortar. She has not smelled anything at all since Oxford. However, we can remember odors, especially when we are prompted by images. Anna tangibly recalls the scent of fresh-squeezed lime, garlic, mustard, ground pepper, and—more fleetingly—smells that she has very rarely experienced: cloves, toasted cumin, and the back-of-the-nose bite of cayenne.

A wisp of aromatic steam (no wider than a single camel hair) curls from the pot to the storey above. There Anna sees a spacious chamber with open balconies on two sides and windows on the others. A huge, crimson, tasseled pillow sits on a carpet of intricate design. A man lies prostrate before this pillow, his hands bound behind his back, his nose to the carpet. Three others stand behind the pillow, wearing turbans, fierce moustaches, and curved swords. And on the pillow itself kneels a young man with soft features, his face turned sideways. He is not looking at the terrified figure before him, but at a window. Anna follows his gaze and sees that on the other side of the glass, a tiny butterfly is beating its wings.

The finger of the Italian man moves across the surface of this page, tracing a line of script from right to left. He pauses for quite a long time, draws a quill from an inkpot, places a piece of parchment on the margin of the book near the script that he has just read, and writes in cursive English: “The Shah doth forget his verdycte, saying, ‘Let the Judges do their Dutie this day. I shall prononce not jugement on any fellowe, even if he denyeth God brayzenly, for I am but a Sojorner heer.’”

Anna’s eye lingers on the yellow butterfly that has moved the king. Then she scans upward and finds a round silk tent supported by a single pole. It fills a garden that must smell of orange trees, azaleas, and loamy soil, to judge by the illustration. The same Shah is again seated, this time on an octagonal, cushioned divan. The same prisoner now kneels comfortably before his lord. According to the note that the Italian translator scribbles, “Akbarr the Magnifycent biddes Ajita Brihaspathi to travelle unto the Lands of the Franks, there to learn whether there be any Frankish Filosofers in this our Ayge.” The Italian crosses out “Filosofers” after he has written it and writes instead: “Men of Reason or sound Minde.”

The blank page on the right is turned (although an embodied viewer would see it as the one on the left). Again Anna sees an iridescent painting set in a broad margin that contains much indecipherable writing. There is a band of sea at the bottom of the picture; a ship is pulling into port. It has a high stern that sweeps down in a smooth, unbroken line to its bow and then sharply up to form a prow, and it carries one long triangular sail. Ajita is sitting cross-legged on the bow with a paintbrush in his hand. Very close inspection reveals that he is painting a scene much like the one that Anna is inspecting now, with himself in it, painting. She sees that he is a young man, clean-shaven, with big eyes, dark skin, and a sensitive and appreciative expression.

The land in the picture is covered with great swirling rocky mountains and cedars that must perfume the clear air. About half way up, Ajita can be seen again, riding on a horse. He has turned his head to face a man with a paler expression and a black turban; they are conversing. Rabbits scurry away from their path, and a bent old beggar tends a campfire by the side of the road. Anna reads scribbled notes as they emerge from the Italian’s pen. They are rather cursory and elliptical, with many words scratched out and question marks left in place of phrases. She fills in the gaps, thinking in her native Dutch:

AJITA: From your perception of that smoke, you infer that there must be fire and heat.

THE CLERIC: Yes, and likewise, from my perception of your movements, I infer that there must be a soul within you. So I maintained earlier in our conversation, as you must recall.

AJITA: But you do not behold the fire, nor the cause of it. You see only the light and smoke. Because smoke has accompanied heat on past occasions in your experience, does it follow that smoke must come from fire, or that the latter causes the former? No. Equally false is the inference that there is a soul wherever we see movement. Does the dust that swirls in the wind possess a soul? There exists only smoke, light, dust, and other objects that we can see. There is nothing secret behind them.

THE CLERIC: What then do you suppose constitutes life?

AJITA: It is a favorable conjunction of observable attributes in motion, like the harmonious combination of strings that forms a chord. When the strings of a sitar are no longer struck, there is no music. Living just is the motion of a physical object.

THE CLERIC: To deny the immortal and incorporeal soul is a blasphemous doctrine that makes you guilty of apostasy.

AJITA: I was never a Muslim; thus I cannot be an apostate. I am of the Charvaka school.

THE CLERIC: In that case, you are a brazen denier of God and your head shall be chopped off your body.

Anna sees that the same two figures recur further up the page, but now Ajita is galloping with his face bent into his horse’s mane. The road climbs in dizzying switchbacks, and the furious cleric charges close behind Ajita with a scimitar over his head.

The page is turned again, revealing another seascape. Now Ajita’s head, still safely attached to his neck, is visible near the bow of a large, three-masted galley whose rows of oars stroke the placid blue water. The ship flies pennants with crescent moons. Ajita looks composed and comfortable on board. He is sailing away from a walled city crowded with minarets and domes of gold and lapis lazuli. A dolphin plays in the wake. The sky is pale blue. It is a pleasant day on a warm southern sea. The artist must be headed to Europe in search of reasonable men.

On the next page, the ship is shown much closer up and it has been rammed by another galley, this one heavily carved and gilded and packed with sinister, pale, bearded men bearing muskets or pikes. Some have red crosses on their tunics. People are leaping off Ajita’s ship or crumpling over with blood stains on their clothes. Ajita’s own face is contorted with terror, his arms are flung toward the heavens, and the slim brown fingers on both of his hands are spread wide. The attacking galley flies a square red flag with a gold, winged and haloed lion.

The same flag flies twice on the next page, over two matching crenellated towers. They are built of brick; a canal separates them. In the distance, Anna sees golden onion domes surmounted by spires and crosses. On one bank of the canal, Ajita stands with some other chained prisoners of various skin-colors, both men and women. He and the other prisoners are bare-headed, barefoot, and downcast, surrounded by men in doublets and hose with skinny legs and wicked looking rapiers. One gentleman passes a purse to another while he leers and points at a willowy young woman of Circassian dress who is holding the hand of a little boy. Another fellow leads away a young male captive by a chain around his neck. Before the page turns again, Anna spots a book mostly concealed under Ajita’s tunic.

The margin of the next page is just a narrow band of plain yellow, with no writing. Two figures fill more of the pictorial space than anyone in the book has so far. They traverse a horizontal road, leaving shadows behind them. The first man wears a peaked steel helmet, a square reddish beard, and a breastplate. He has a pink scarf or kerchief tied around his wrist. His silver shield is dented from many blows and bears a blood-red cross, but his face seems rather cheerful. He rides a horse that has an angry look and is grinding and foaming at its bit. Behind this mounted knight walks Ajita Brihaspathi in a plain leather jerkin of European cut and a pointed cap. Anna wonders whether Ajita has been purchased by the knight and is being led through Europe as a slave. Or perhaps the knight has freed or rescued him and is now employing him as a page.

This picture, unlike those that have come before, has a horizon. Flowing toward it is an expanse of fields and vineyards interspersed with steeples and cottages that diminish and grow indistinct in the distance. Anna sees this rolling landscape through the eyes of the artist, presumably Ajita, who has made the details look novel and exotic. The scale sometimes seems wrong: for example, the cross that surmounts each church tower is far too big. But Ajita has perceptively observed how a house can be constructed of black timbers, the spaces filled with whitewashed mud, and the roof made of neatly pleated straw; or how martins hang their nests from the eaves. And he has noticed how peasants throw sticks to knock acorns to the ground for their pigs.

The fields here are open and worked in common by rows of threshers. As in some backward parts of Flanders and England, each man still plants scattered strips of land that are his own by inheritance. But it is most efficient for the whole village to harvest together; and everyone may hunt or graze his animals in the stubble once the grain is cut. Such places—Anna thinks she may be looking at Berry or Burgundy—are governed by customs, superstitions, endless gossip shared in impenetrable dialects, and family ties that verge on incest.

As Anna watches more pages turn, the pastoral mood shifts to tragedy. The red-bearded knight and Ajita encounter peasants who flee their homes in evident distress. A woman holds a baby in her arms and weeps. The muscles of her long twisted limbs show through her robes, as in a print one could buy in Antwerp or London. An old man staggers along on a crutch, looking back fearfully like Adam cast out of Eden. A boy and a girl in rags hold hands as they run. Smoke wafts over their heads, rising from the thatch of a cottage that is burning in the distance.

Soon the source of all this suffering is revealed. Men with their visors over their faces are axing down doors, smashing shutters, igniting thatch. They wear livery with the device of a silver ostrich that holds a horseshoe in its beak. The red-headed knight knows his duty: he vows an errand of mercy. Someone is oppressing the weak, ravaging their women, and besmirching the tenets of chivalry. “On, faithful retainer!” cries the redhead as he spurs his steed and drops his lance into place for a charge. Ajita trots behind him on foot, looking warily left and right.

Anna imagines that she hears Ajita’s nervous voice speaking in Dutch. “Master,” he pants, “before you gird yourself for a fearsome battle against overwhelming odds and we both get chopped up like almonds for a cooking paste, might this not be an excellent time for me to tell you that story from my homeland? Remember?—I said I’d illustrate a romance for you in bejeweled pages like the gift books that my Shah has sent your grateful Queen? You said you’d translate my story into French alexandrines and sell it with my illustrations for an enormous sum. Despite your astounding courage, might, dexterity, valor, etcetera, there is a pretty good chance that this will be my last afternoon among the living, for it’s going to be you with a lance and me with my paintbrush against about fifty Franks and those enormous axes. Don’t you want to hear my story first, and then go off on your errand of mercy?”

“Fine,” says the Knight, “but make it succinct. No digressions or similes; we can add those later when you paint your miniatures. No tropes or descriptions—just the plot. That’s what makes a book sell.”

“Very well,” says Ajita, “Once upon a time, and may good be our reward, and may evil strike him who wishes evil—“

“I told you to omit everything unnecessary. That certainly includes a benediction, which doesn’t belong in a romance in the first place. Besides, I thought you said you were an atheist.”

“I’m just relating the story as it is always told in my homeland. If I had the wit to invent literature of my own, I’d certainly skip all prayers and other pious nonsense. However, as you know, I am a painter and not a poet. I’m reciting the words verbatim from my aunts.”

“Fair enough, but even a witless fellow should be able to delete unnecessary verbiage and digressions from a story he’s memorized. Anyway, you must hurry—the villainous Frenchmen are moving away, and I shall lose my chance to smite them.”

“I was trying to say,” says Ajita, “that once upon a time in a mountain village of Kashmir there lived a goatherd, and this goatherd, who will be the hero of my story, was called, ah, Lopay. And this Lopay was deeply in love with a shepherdess called, er, Sumeru. And this Sumeru was the daughter of a rich herdsman, and this herdsman—“

“By the Queen’s white paps, man, get on with it!” the redhead cries. “No more repetitions! Half of these French scoundrels are out of sight entirely.”

“I am endeavoring, sir, to translate into a harsh European tongue the rhythms and cadences of the East,” says Ajita huffily, but with diminishing fear in his voice now that the prospects of battle seem to be fading.

“As you like then,” says the redhead. “Proceed. I need some time to decide which way to charge, now that most of the rogues in armor have withdrawn.”

“As I was saying, master, the herdsman Lopay was in love with the shepherdess Sumeru, who, truth be told, was rather large and bulky, almost a man’s size and girth around the shoulders; and I had begun to notice quite a moustache on her upper lip—”

“You had noticed? You mean, you knew this wench? I thought this was an ancient tale of the orient.”

“That was a painter’s mistake: thinking that I saw whereof I spoke. I never had the honor personally to behold Sumeru, because her story was passed down to me from our ancestors. They relate that Kalki—a troublesome god, or as you might say, a devil—chose to poison the love between Lopay and Sumeru by tempting the shepherdess with other boys and then turning Lopay’s heart to jealous rage. One day, Lopay was so fed up that he decided to drive his whole flock away to another valley entirely, where he wouldn’t even have to see Sumeru again. However, as soon as Lopay began to shun and despise her, Sumeru’s love was restored and she became passionate about him.”

“That’s always the way,” says the redhead absent-mindedly. “But look, you must get to the point. I see some armored Frenchies passing by, and if I don’t charge them in a minute or two, they’ll get by without a scrap.”

“Yes, master. To cut right to the heart of the matter, young Lopay had to drive his 530 goats over some dry foothills, down some cool passes, through some fragrant forests, and at last across the Jhelum river, while all the time Sumeru was whining and moping about fifty paces behind him. Well, Lopay reached the banks of the fabled Jhelum at last, and there he found a boat lying free and ready to take him across. Alas, it was only big enough for him and a single goat. So he ferried one goat across the treacherous river, left it to graze amid the ferns, and returned for a second goat. He took the second goat across the river, left it contentedly with the first, and rowed back again. He picked up the third goat, a plump brown nanny of about two years—”

“You jackanape! You don’t have to tell me about each and every goat! The scoundrels have completely left the village and there are no iniquitous heads for me to lop off.”

“Well, how many goats did I tell you about already? In the interests of time, I’m willing to resume where I left off and not repeat myself; but I’ve lost track of the whole story now. You should have kept count while I ran through the animals ….”

Anna’s master, Dr. Burby, often notes that time moves in only one direction. To return a clock or any other mechanism to a state that existed in the past would require energy and intelligence, the use of which alters the world irreversibly. There is no going back, no stopping the downward flow. Yet we can divert time by telling stories that emerge limitlessly from our memories or imaginations. When Anna was a little girl in Bruges, her mother’s stories used to forestall the night, and that is what she misses most.

Another page turns. The redhead knight is staying behind in France to supervise the rebuilding of the ransacked village; the raiders seem to have moved on without a fight. Ajita is on his own now, bearing a letter from the knight to his beloved. With the letter visible in his hand, he crosses the English Channel—so Anna presumes—in a two-masted herring buss and lands in a port that looks like Southend, down where the Thames loses its direction and definition as its fresh water merges irreversibly with the sea. A single illustration shows Ajita’s progress on horseback through a landscape of hop fields and sheep.

On the last page of the book, Ajita is indoors, facing a blond, round-faced young woman in a simple hoop skirt. She has blue eyes and freckles on her cheeks and plump arms. Her face is friendly but impassive. Ajita is slim and slightly shorter. These two modeled and glossily finished figures stand like cutouts from an oil painting. Anna’s vision moves behind them to the paler, flatter, more evenly lit background of beams, flagstones, bay windows, low ceilings, and an oak desk. She stares at this space, which seems reasonably coherent and plausible—a Northern European interior. But there is something wrong with it, something off. Anna has a strong sensation that this image is like a memory, yet everything has been pulled out of proportion and dyed an unfamiliar color. The figures in the foreground begin to fade as the space behind them grows more vivid, darker, and (to Anna’s eyes) more lifelike. The angles and ratios shift rapidly as the whole room coalesces into a new shape around her. The beams in the ceiling now lead toward a single point that flies across Anna’s field of vision until it comes to rest to her left. Motes now swim in the bright air within the bay of the window. Edmund Burby’s cell, the Tower of London, the Italian reader’s hand—all that has melted away as Anna crosses a familiar room near Beckley in Oxfordshire. The people are gone, the room is empty, but there are papers on the desk.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:53 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 20, 2009

village democracy in India

One of the most remarkable innovations in democracy comes from India, where the Constitution requires every village (but not urban areas) to have both elected councils and empowered open meetings called "gram sabhas" (GS's). Vijayendra Rao of the World Bank and Paromita Sanyal of Wesleyan write, “The GS has become, arguably, the largest deliberative institution in human history, at the heart of two million little village democracies which affect the lives 700 million rural Indians.” PDF

Apart from the scale of this experiment, its most remarkable features are (1) the right to active participation that is enshrined in the Indian Constitution, and (2) the steps required to promote equality of gender and caste.

As the government itself explains, Article 40 of the original Indian Constitution required "that the State shall take steps to organise village panchayats [councils] and endow them with such powers and authority as may be necessary to enable them to function as units of self-government." But there were problems with the representativeness, fairness, and power of the panchayat system. As a result, in 1992, the Indian "Constitution was amended to … provide for, among other things:

- direct elections to all seats in Panchayats at the village and intermediate level, if any, and to the offices of Chairpersons of Panchayats at such levels;

- reservation of seats for the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes in proportion to their population for membership of Panchayats and office of Chairpersons in Panchayats at each level;

- reservation of not less than one-third of the seats for women;

- devolution by the State Legislature of powers and responsibilities upon the Panchayats with respect to the preparation of plans for economic developments and social justice and for the implementation of development schemes;

- [funding for the Panchayats from] grants-in-aid [and from] designated taxes, duties, tolls and fees;

- barring interference by courts in electoral matters relating to Panchayats.

There must be a gram sabha in each village at least once per year, although I think that is a statutory provision and not contained in the Constitution itself. "A Gram Sabha may exercise such powers and perform such functions at the village level as the Legislature of a State may, by law, provide." Apparently, some make substantial decisions about spending and planning.

The most remarkable impact of this reform has been to strengthen the confidence, standing, and voice of the poor, of women, and of low-caste individuals. Rao and Sanyal conclude that the “GS facilitate the acquisition of crucial cultural capabilities such as discursive skills and civic agency by poor and disadvantaged groups. ... The poor and socially marginalized deploy these discursive skills in a resource-scarce and socially stratified environment in making material and non-material demands in their search for dignity.”

Posted by peterlevine at 2:30 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 19, 2009

questions for Sen. Grassley

"I think that he is a good person, and good-intentioned. But I believe he didn't serve in government long enough to understand really how things work... He really does not have an understanding of how Congress operates."

-- Sen. Charles Grassley (R-IA), in a radio interview, about President Obama.

Senator, do you think that the Congress you understand so thoroughly (having served in it since 1974) operates well? Do you think that the American people hold its processes and leaders in high regard? What have you done as a sometime committee chair and leader to improve how it operates? If you had a chance to "explain" the process to our relatively young president, would you be able to justify what you explained?

Posted by peterlevine at 10:25 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

August 18, 2009

health co-ops from a civic perspective

Senator Conrad and some others are promoting health insurance co-ops as alternatives to a government-run insurance option. The liberal critique is that they would be small and ineffective competitors to private insurers, many of which enjoy quasi-monopolies. In today's New York Times, Bob Herbert advises, "Forget about the nonprofit cooperatives. That’s like sending peewee footballers up against the Super Bowl champs." It has also been noted that we already have non-profit health insurance options, like Blue Cross/Blue Shield, that charge high rates and dominate local markets. So the problem is not profit, per se, but the lack of competition, regulation, and accountability.

On the other hand, there is a movement that sees major potential in co-ops and other alternative economic arrangements. According to community-wealth.org, there are 21,840 co-ops in the United States, with annual revenues of $273 billion. So this is not a marginal or amateur sector, although there are only a few significant examples in the health field.

Co-ops can be structured so that they are forbidden to move, thus addressing the problem of capital mobility that undermines democratic governance. They can also be structured so that interested citizens have opportunities to become leaders. To be sure, some co-ops end up looking exactly like regular for-profit firms, without the actual profit line. Ace Hardware is a co-op owned by the store owners; I'm not sure that makes any difference to its customers. But a health co-op could have by-laws that encouraged participation, and the federal subsidies that are being considered on Capitol Hill could be contingent on such rules. If the start-up subsidies were big enough, I doubt there would be an insuperable barrier to gaining a large market niche.

Here are some advantages of a more participatory structure:

- People deeply distrust government, so it may be smart politics to build a more progressive infrastructure that includes mechanisms for enhancing trust, such as local ownership.

- In numerous cases around the world, public participation has been found to reduce corruption and waste. When people have decided what to spend money on, they watch to see if it is spent as promised. When the money vanishes, they rebel.

- Participation in co-ops would increase people's civic skills and their expectations that other major institutions will treat them respectfully.

- Health decisions involve complex scientific and technical issues--but also irreducible value judgments that cannot be made "scientifically." Co-ops can include deliberative bodies that make value judgments and tradeoffs, accountably and transparently. Moreover, those decisions can be made differently in different parts of the country, thus reducing the intensity of our cultural battles. (Yet co-ops would also be regulated by the federal government to protect rights that Congress deemed essential.)

- Co-ops could contribute to political pluralism by lobbying in the interests of their members.

Of course, "co-op" is not a magic word that solves all political and social problems. Everything depends on what the co-ops are like. But we have considerable experience now with alternative economic arrangements inside of capitalism, and we could seize on the health co-op idea to make real progress.

[As a note to my fellow proponents of active citizenship, deliberative democracy, etc.--I really think we need to drop our neutrality and start supporting policies that would enhance citizenship. If health co-ops are not the right examples, because the liberal economic critique is correct, we need to look for other openings. We can't be for abstract procedures alone.]

Posted by peterlevine at 11:57 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 17, 2009

the role of government (the big picture)

The size and scope of government is one of our most basic debates, and underlying it, I think, is a debate about the past. Conservatives think the government began very small and has grown inexorably, diminishing freedom. They argue that expanding the government's role in health care would mark another step on the long road to serfdom. Supposedly, George W. Bush lost his way by enlarging the government, and that is why Republicans were beaten in 2008. For their part, liberals think that our age has been marked by deregulation, spending cuts, neoliberalism, and corporate-led globalization. They see the Democratic health reform proposals as very modest countermeasures.

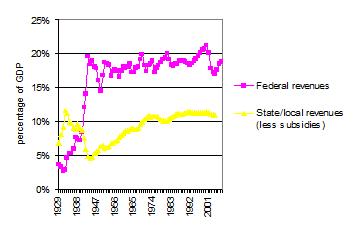

The truth seems more complicated than either perspective, although I'd give liberals the edge overall. One measure of the size of government is the amount of revenue it collects, almost all in the form of mandatory taxes. As the following graph shows, federal taxation as a percentage of GDP doubled in the Great Depression and more than doubled again during World War II. It has been fairly stable since then. It was just half a percentage point lower when Ronald Reagan left office than when he was sworn in. The biggest decline was during the George W. Bush years, although we borrowed to make up for the lost revenue, so we will have to pay that back later. (It's very hard to believe that Bush would have been more popular if he had cut government spending and reduced the deficit, as conservatives are now arguing.)

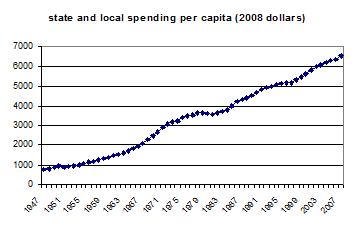

Meanwhile, state revenues (the yellow line, above) have risen steadily. Below is the other side of that coin: the trend in per capita inflation-adjusted spending by states and localities:

I think both sides in the debate may be a little surprised to find that the clearest trend is a steady increase in the size of government during the age of neoliberalism--but at the state and local level, not in Washington.

The government also regulates, and that's a harder matter to capture in a graph. But consider that in the 1970s, the federal government regulated financial markets, school assignments (because federal judges imposed desegregation plans), and the physical planning of major cities. It has stepped back in all those areas, although it has added some environmental and safety regulations.

Summing up, I'd certainly dispute the "Road the Serfdom" thesis. The national government is probably somewhat less intrusive in 2009 than it was in 1949. On the other hand, the left should recognize that even in an age of "neoliberalism," federal taxation has remained steady, and states are spending more every year.

Leaving aside cheap and hyperbolic rhetoric, both sides in Congress agree about roughly 80% of the federal budget (the existing entitlements, debt service, and the broad outlines of military spending), so their differences are subtle. They are not arguing about the fundamental nature of the republic but about the kinds of variation we see in the first graph during the decades since 1945. For example, the projected cost of the health care plan (at most, $1 trillion over ten years) is well below 1% of GDP (which is $13.8 trillion per year now, and rising). So the health care plan would cause a hard-to-discern upward wriggle in the first graph above.

Data for the first graph provided under a Creative Commons License by Daniel Schmelzer. Federal revenues for 2005-2007 added from CBO, Budget and Economic Outlook, 2008, table f-5. Second graph is my analysis from the Statistical Almanac of the United States.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:50 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 14, 2009

Amazon ranking

I admit that one of my time-wasting, egocentric computer activities is to check the day's Amazon rank of my more recent books by means of a tool called Title Z. It gives you graphs of all the titles you choose on one page.

The Amazon rank of any given book seems to pop around pretty randomly and must be sensitive to even one purchase. But the idea behind Title Z is that you can get meaningful information if you take a snapshot every day. I don't know whether that's true, but here is the daily sale's rank of my The Future of Democracy book since August 17, 2007:

Low is good: a score of 1 would mean that the book was Amazon's current best-seller. Today happens to be the worst score ever. Who knows if that's meaningful, but there do seem to be trends in the graph (not just noise). For instance, the fall semester of 2008 was a good time for sales; the current summer has been slow.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:18 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 13, 2009

talking about the health care forums and civil discourse

This morning, I was on "Radio Times" with Marty Moss-Coane. That's a call-in program of WHYY-FM in Pennsylania. The MP3 file is here, for those who like to listen online or download podcasts.

My fellow guest was Martin Carcasson from Colorado State, a great proponent and practitioner of deliberative democracy at the grassroots level. I think we agreed that the protesters are exercising free speech, expressing views that belong in the political debate, and should be treated respectfully as citizens (not as robots operated remotely by special interests). On the other hand, a format for discussion that encourages angry individual speeches is pretty alienating for most citizens and is a poor source of information or enlightenment. We could do better--although both Martin and I noted that the political and media environment work against deliberative politics; and even good forums might be vulnerable to hostile takeovers.

One great model is Oregon Health Decisions, an elaborate series of public discussions that created the Oregon Health Plan. Citizens were able to make difficult tradeoffs--for example, between preventive and palliative care--and produce a durable policy. The question is whether that would be possible under the harsh and competitive conditions of national politics today.

After the show, we got a long email response from a listener who wanted to document (with 17 links to stories on TPM and Huffington Post, among other sources), that "these disruptive and anti-democratic tactics were designed and spread by right wing organizations and vested industry and Republican interests." I think some angry speakers have been mobilized by interest groups. (By the way, mobilization is a legitimate democratic technique, as is the technique of arguing that one's opponents have been manipulated.) At the same time, I believe that deep and broad skepticism about government is another major cause of these protests. It isn't all manufactured, even if some of it is. We progressives ignore that skepticism at our peril.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:54 PM | Comments (3) | TrackBack

August 12, 2009

why have town hall meetings at all?

Members of Congress are doing their usual thing--holding "town hall meetings" that are really public Q&A sessions on major pending issues. This summer, the main topic is health care reform. What is unusual is the hostile reception that politicians are experiencing (although I'm not sure what proportion of the negative comments are truly inflammatory ones, like those covered in the media). As a result, some Members have already decided not to hold town hall meetings at all, and the whole practice might soon disappear. That prospect leads Matt Yglesias to reflect:

Members of Congress are doing their usual thing--holding "town hall meetings" that are really public Q&A sessions on major pending issues. This summer, the main topic is health care reform. What is unusual is the hostile reception that politicians are experiencing (although I'm not sure what proportion of the negative comments are truly inflammatory ones, like those covered in the media). As a result, some Members have already decided not to hold town hall meetings at all, and the whole practice might soon disappear. That prospect leads Matt Yglesias to reflect:

I don’t understand why members of congress are holding these town halls. There’s been so much focus on the spectacle of the whole thing that nobody’s really stepped back and explained what the purpose of these events are other than to give us pundits something to chat about. Obviously this is not a good way of acquiring statistically valid information about your constituents’ opinions. And it doesn’t seem like a mode of endeavor likely to increase the popularity of the politician holding the town hall. The upside is extremely limited, and you’re mostly just exposing yourself to the chance that something could go wrong.

Yglesias is asking how politicians benefit from these events (in a narrow sense). A more important question is whether town meetings have public benefit--which would offer a different kind of reason for holding them. I would say ...

On one hand, there is no good reason to hold the kind of "town meetings" we are used to. That phrase invokes the old New England deliberative forums in which citizens come together to make collective decisions. The reality, however, is a public hearing with a small group of self-selected activists who ask questions one by one. That format is easy to manipulate and likely to turn unpleasant; it rewards strategic behavior rather than authentic dialog; and it reinforces a sense that the politician and citizens are profoundly different. (The politician has responsibility but cannot be trusted; citizens have no power but only a right to express individual opinions.)

On the other hand, we need real public discussions that include politicians along with other citizens. The purpose of such discussions is not to find out what the public thinks already. As Yglesias says, a random-sample poll is better for that. And its purpose is not to sell the public on a position; for that, mass advertising works better. The purposes of discussion are rather to encourage people to see issues from other perspectives from their own, to develop new and better ideas, to enhance voters' ability to judge their representatives as deliberators, and to strengthen local ties and relationships that lead to civic change. For example, citizens who discuss health care reform might not only develop opinions about federal legislation but also decide to launch a new initiative in their town.

Without deliberation, as Madison warned, "The mild voice of reason, pleading the cause of an enlarged and permanent interest, is but too often drowned, before public bodies as well as individuals, by the clamors of an impatient avidity for immediate and immoderate gain."

To achieve deliberation, process is important. People need to talk among themselves in diverse groups, whether in study circles, National Issues Forums, or at tables in a 21st Century Town Meeting organized by AmericaSpeaks. There must be moderators and good background materials. Elected representatives should be observers, or maybe peer participants, but not lone figures on the stage.

The Obama Administration could have used public deliberation as a way of getting a health care bill. That would have required a large-scale, organized public discussion with moderators and rules. The Administration chose, instead, to drive the bill through Congress quickly, using their mandate. They may succeed, and there was a case for speed. But they have encountered--not only organized ideological opposition--but also deep public distrust of government. If they fail, this will be the cause.

Here are two potential "theories of change":

1. Run a presidential campaign promising to expand the role of government in health care, get more than half the electoral votes and seats in Congress, write and pass the bill, and trust that the results will ultimately be beneficial enough that people will come to like and trust the new federal health care program.

2. Try to build a health reform plan in dialog with the public by organizing a large-scale deliberation about the content of the bill and by considering participatory mechanisms for the ongoing delivery of health care. (Co-op insurance plans might have potential for that purpose.)

The Administration chose the former strategy, and we'll see if it works. I hope it does, because I think the House bill will benefit the public if passed. It is also possible that a deliberative process would have been subverted by partisan and ideological forces (although there are techniques that can protect deliberation to a degree). At any rate, I hope the Administration will try a deliberative approach to some other issue.

Posted by peterlevine at 1:31 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 11, 2009

the hourglass

One grain of sand is not a heap of sand.

If one grain is no heap, two cannot be.

If two are not a heap, neither are three.

So keep adding grains from your open hand--

One million's no heap if built up from one.

But if you could find such a thing as a heap,

You'd do no harm by taking part to keep.

A heap's still a heap when one grain is gone.

Now say that this pile of sand's in a glass,

With a neck that allows the grains to slide through,

One or two at a time--now and then, a few--

Til the sand's at the base and no more will pass.

Instant by instant, time, like sand, creeps.

A life is just a heap of time, and so,

Though each day must fall, the life cannot go.

(Unless we believe that there really are heaps.)

Posted by peterlevine at 9:16 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 10, 2009

building public capacity

At last week's meetings in Washington, about 100 proponents of democratic reform, representing several different traditions and flavors, came together to develop a common agenda that was welcomed by the White House as advice. I was one of a fairly substantial minority that put the development of civic skills on the agenda. It occurs to me that civic skill-development is the defining goal of my own work and of the main organizations I work for, CIRCLE and the Tisch College of Citizenship and Public Service.

Skill- or capacity-development is always a central purpose and outcome of admirable popular movements, such as the Civil Rights Movement in the US, the anti-Apartheid movement in South Africa, or the Labor Party in Brazil. The need for skills--as well as confidence and knowledge--is very obvious when one works with disadvantaged people. In contrast, good-government reformers tend to focus on procedural changes and may overlook the need for people to change in their minds and hearts.

I worked for two years for Common Cause and remain a strong supporter of theirs (and of the League of Women Voters, of which I am a member). I agree with them that it's essential to reform the rules of campaign finance, legislative districting, and the Senate. But there is a reason this is a middle-class agenda. Although procedural reforms would disproportionately benefit low-income people, low-income people are not likely to fight for such reforms or use the new rules to their advantage. These matters are too abstract and distant to engage without specialized skills. (But working-class people have other skills that they can use effectively in social movements.)

At CIRCLE, we study how young people develop the skills they need to be effective citizens. At Tisch College, we teach such skills and are becoming increasingly deliberate about selecting the important skills and developing appropriate curricula. These are just two examples of initiatives underway in civil society.

For the government, I would recommend the following agenda:

- As AmeriCorps is tripled in size, make it an essential goal to develop the civic skills of participants.

- As the Administration implements the remarkable presidential memorandum on transparency, participation, and collaboration, make sure that each project and program that involves civic engagement includes an element of skill-building for the public and for federal managers.

- Make civic education a high priority in federal education law.

- Invest in federal programs that provide trainings, conferences, toolkits, etc. for civic groups that collaborate with the government.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:50 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 5, 2009

going offline

My family and I are taking a short New England vacation until Friday, when I'll fly to San Francisco for the American Sociological Association's annual conference. On Saturday, I'll speak at a presidential plenary session of the ASA, entitled "Why Obama Won (and What that Says about Democracy and Change in America)." Until then, I'm planning to go offline and avoid both the consumption and the production of blogs.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:12 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 4, 2009

interacting with the administration

(Washington, DC): I'm at Strengthening Our Nation's Democracy II, a conference organized by Demos and by two organizations on whose boards I serve, AmericaSpeaks and Everyday Democracy. About 100 proponents of democratic reform have convened to develop a common agenda. One goal is to interact with the White House, which has sent four high-level officials to speak and some others to participate in discussions. Their remarks are "off the record," to permit candor. For that reason, and also because of the complexity and richness of the conversation, I will not attempt to summarize the way they think about civic renewal and democracy.

But I am struck by a problem. Some members of the administration, not including the president, are probably committed to "interest-group liberalism." They think their job is to pass fair, just, and helpful legislation. They see a public divided into organized interest groups, whose leaders represent their rank-and-file. Unfortunately, interest groups' power is unequal: the US Chamber of Commerce has much more power than the National Coalition for the Homeless. So a major task of a progressive administration is to inform, listen to, and mobilize organizations that represent the disadvantaged. Meanwhile, legislation is very complicated, elaborate, and fast-moving. Most Americans cannot possibly follow all the details, so the White House has both the need and the ethical responsibility to discuss pertinent aspects of each proposal with interest groups that especially care.

Most of participants at this conference, on the other hand, reject interest-group politics. The political reform groups (League of Women Voters, OpentheGovernment.org, etc.) have a progressive model, in which the "common good" means abstract and general rules that apply to all. The proponents of deliberation and dialog want open-minded and diverse citizens to discuss issues, learn from one another, and break out of interest-group categories. The popular education and civic education people want to go straight to the grassroots and empower people, without organized and professionalized intermediaries.

I suspect that when White House staffers look down from the podium at our group, they feel reinforced in some of their interest-group liberal assumptions. They see a predominantly white, upper-middle-class, professional audience with a significant sprinkling of professors and Beltway experts. They do not see representatives of the public interest, but rather a particular special interest--the "good government" lobby.

This is partly unfair, because the streams of political reform that are represented in the room have deep resonance for disadvantaged American communities and often emerged in the Civil Rights Movement or community organizing. But the impression is real and is substantially our fault. When we pull together leaders for high-level meetings, we somehow end up with a bunch of Ivy League professors and Washington lawyers.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:25 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 3, 2009

the view from South Africa

(Washington, DC) Xolela Mangu, a distinguished South African social scientist and columnist, joined our conference last week on the Obama civic agenda. In his national column, he reflects on "service" (with its hints of moral obligation, on one side, and dependency on the other) versus civic empowerment:

LAST week I participated in a cross-Atlantic conference with officials and academics closely aligned with the Obama administration.

On this side, I was joined by the distinguished scholar-activist, Harry Boyte.

The conference was convened to ask one question: how far has Obama gone in fulfilling his campaign promise of making active citizenship the centre of his administration?