« January 2009 | Main | March 2009 »

February 27, 2009

Everyday Democracy

I'm proud to announce that I've joined the board of the Paul J. Aicher Foundation (official release here). That's an operating foundation that funds one major project: Everyday Democracy. In turn, Everyday Democracy assists communities in holding diverse conversations about issues that matter to them. As explained in this handy history, the late and much loved Paul Aicher revived Study Circles in the United States in the 1980s. (They had a heritage here, and were also common in Scandinavia and South Africa--as I understand.) The organization he created was called the Study Circles Resource Center, but its projects multiplied and shifted, and it finally made sense to rename it.

I'd place Everyday Democracy in two fields, for the sake of introducing its work. First, it's part of the deliberative democracy movement--indeed, it is a leader in that movement. Citizens' deliberations vary in many respects: they can be small or large; randomly-selected, demographically representative, or open to volunteers; episodic or continuous; sponsored by governments, consortia, or citizens; focused on local, national, or global issues--and so on. As it evolved in the US, the Study Circles model developed particular characteristics: local, community-wide, self-selected but diverse, and sustained over several months. I am in favor of a rich ecosystem of experimentation, but I admire this model, at least as an important example. It is less about learning what the public as a whole would say if it were informed (which is the purpose of random selection), and more about convening diverse activists--and activists-to-be--for open conversations.

Which brings me to the second field in which Everyday Democracy works: community organizing. Again, there are many forms of community organizing, which vary in respect to whether they draw ideologically diverse or homogeneous citizens; emerge from religious congregations, unions, parties, or civic organizations; emphasize discussion, political advocacy, consumer organizing, or economic activity--and so on. Everyday Democracy is particularly strong on discussion and diversity of participants. It can, by the way, comfortably coexist with other forms of community organizing.

Posted by peterlevine at 2:21 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 26, 2009

learning about social media

My head is swimming with recent conversations that touch on social media, civic engagement, and young people. I'd define "social media" as any of the Internet technologies that make it easy to distribute your own creations and form relationships with others online. These tools include "friending" people in Facebook, commenting on their blogs or YouTube videos, or following them on Twitter.

Yesterday, I met with my Tufts colleague Marina Bers, who (among many other projects) has created a virtual world for in-coming Tufts undergraduates who build an ideal university before they attend the real one. A movie of the 2006 summer project is really remarkable.

In the evening, I was on a panel at Harvard with the psychologist Howard Gardner, my friend Joe Kahne (who is one of the most acute and productive scholars of civic education), and Miriam Martinez, who represents one of the best programs for high school students, the Mikva Challenge in Chicago. It was an informal conversation, ably steered by Gardner, and we talked a bit about what kinds of social media use constitute "civic engagement." (Are you civically engaged if you join a Harry Potter fan group?)

And then this morning, I presented our own social media tool, YouthMap, to the Boston Social Media breakfast ( #SMB12 ). That's a gathering of about 75 business, tech, and activist types who meet in a jazz club--at 8 am--to examine new tools and strategies.

And then this morning, I presented our own social media tool, YouthMap, to the Boston Social Media breakfast ( #SMB12 ). That's a gathering of about 75 business, tech, and activist types who meet in a jazz club--at 8 am--to examine new tools and strategies.

Speaking just for myself ... I'm finding Facebook increasingly fun now that the demographics have tipped and lots of us non-hip Generation-Xers are using it. I watched the President speak with Facebook open and got a kick out of the comments. Blogging is a big part of my life--both writing and reading--but it's not really a "social medium" for me. I mostly read blogs by professional reporters and I compose my posts as fairly conventional short editorials. I have a Twitter login but haven't found a way to use it that makes me comfortable.

Posted by peterlevine at 4:31 PM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

February 25, 2009

the Kennedy-Hatch Serve America Act

Last night, the president spoke strongly and explicitly in favor of the Kennedy-Hatch Serve America Act, which would expand the number of slots for paid national and community service and increase the quality of those positions. I have blogged in support of that legislation, and my post evolved into an article entitled "The Case for Service" in Philosophy & Public Policy Quarterly (PDF). Basically, I see service as experiential education that builds job skills, increases young adults' odds of attending college, and teaches them civic skills so that they can address problems in their communities. The "service" dimension is important educationally because many (although probably not all) young people learn better when they have opportunities to contribute. AmeriCorps and related programs are also extremely important for equity. The more advantaged half of the young population that attends college receives educational opportunities subsidized by the public. But those who do not continue formal education beyond high school find that almost all government-funded educational programs have age limits of 18 or 21. Working-class youth are basically subsidizing their more advantaged peers' learning opportunities with their tax dollars. Service programs such as YouthBuild, Public Allies, City Year, and the National Civilian Community Corps (among others) help to right this imbalance by offering opportunities to young adults who may not be on the college track.

Posted by peterlevine at 1:03 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 24, 2009

the politics of negative capability

Zadie Smith's article "Speaking in Tongues" (The New York Review, Feb 26) combines several of the fixations of this blog--literature as an alternative to moral philosophy, deliberation, Shakespeare, and Barack Obama--and makes me think that my own most fundamental and pervasive commitment is "negative capability." That is Keat's phrase, quoted thus by Zadie Smith:

- At once it struck me, what quality went to form a Man of Achievement especially in Literature and which Shakespeare possessed so enormously—I mean Negative Capability, that is when man is capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.

Other critics have noted Shakespeare's remarkable ability not to speak on his own behalf, from his own perspective, or in support of his own positions. Coleridge called this skill "myriad-mindedness," and Matthew Arnold said that Shakespeare was "free from our questions." Hazlitt said that the "striking peculiarity of [Shakespeare’s] mind was its generic quality, its power of communication with all other minds--so that it contained a universe of feeling within itself, and had no one peculiar bias, or exclusive excellence more than another. He was just like any other man, but that he was like all other men." Keats aspired to have the same "poetical Character" as Shakespeare. Borrowing closely from Hazlitt, Keats said that his own type of poetic imagination "has no self--it is every thing and nothing--It has no character. … It has as much delight in conceiving an Iago as an Imogen. What shocks the virtuous philosop[h]er, delights the camelion poet.” When we read philosophical prose, we encounter explicit opinions that reflect the author’s thinking. But, said Keats, although "it is a wretched thing to express … it is a very fact that not one word I ever utter can be taken for granted as an opinion growing out of my identical nature [i.e., my identity]."

In Shakespeare's case, it helps, of course, that he left no recorded statements about anything other than his own business arrangements: no letters like Keats' beautiful ones, no Nobel Prize speech to explain his views, no interviews with Charlie Rose. All we have is his representation of the speech of thousands of other people.

Stephen Greenblatt, in a book that Smith quotes, attributes Shakespeare's negative capability to his childhood during the wrenching English Reformation. Under Queen Mary, you could be burned for Protestantism. Under her sister Queen Elizabeth, you could have your viscera cut out and burned before your living eyes for Catholicism. It is likely that Shakespeare's father was both: he helped whitewash Catholic frescoes and yet kept Catholic texts hidden in his attic. This could have been simple subterfuge, but it's equally likely that he was torn and unsure. His "identical nature" was mixed. Greenblatt argues that Shakespeare learned to avoid taking any positions himself and instead created fictional worlds full of Iagos and Imogens and Falstaffs and Prince Harrys.

What does this have to do with Barack Obama? As far as I know, he is the first American president who can write convincing dialog (in Dreams from My Father). He understands and expresses other perspectives as well as his own. And he has wrestled all his life with a mixed identity.

Smith is a very acute reader of Obama:

- We now know that Obama spoke of Main Street in Iowa and of sweet potato pie in Northwest Philly, and it could be argued that he succeeded because he so rarely misspoke, carefully tailoring his intonations to suit the sensibility of his listeners. Sometimes he did this within one speech, within one line: 'We worship an awesome God in the blue states, and we don't like federal agents poking around our libraries in the red states.' Awesome God comes to you straight from the pews of a Georgia church; poking around feels more at home at a kitchen table in South Bend, Indiana. The balance was perfect, cunningly counterpoised and never accidental.

The challenge for Obama is that he doesn't write fiction (although Smith remarks that he "displays an enviable facility for dialogue"), but instead holds political office. Generally, we want our politicians to say exactly what they think. To write lines for someone else to say, with which you do not agree, is an important example of "irony." We tend not to like ironic leaders. Socrates' "famous irony" was held against him at his trial. Achilles exclaims, "I hate like the gates of hell the man who says one thing with his tongue and another in his heart." That is a good description of any novelist--and also of Odysseus, Achilles' wily opposite, who dons costumes and feigns love. Generally, people with the personality of Odysseus, when they run for office, at least pretend to resemble the straightforward Achilles.

But what if you are not too sure that you are right (to paraphrase Learned Hand's definition of a liberal)? What if you see things from several perspectives, and--more importantly--love the fact that these many perspectives exist and interact? What if your fundamental cause is not the attainment of any single outcome but the vibrant juxtaposition of many voices, voices that also sound in your own mind?

In that case, you can be a citizen or a political leader whose fundamental commitments include freedom of expression, diversity, and dialogue or deliberation. Of course, these commitments won't tell you what to do about failing banks or Afghanistan. Negative capability isn't sufficient for politics. (Even Shakespeare must have made decisions and expressed strong personal opinions when he successfully managed his theatrical company). But in our time, when the major ideologies are hollow, problems are complex, cultural conflict is omnipresent and dangerous, and relationships have fractured, a strong dose of non-cynical irony is just what we need.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:03 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 23, 2009

consolation of mortality

I just finished Jonathan Barnes' Nothing to be Frightened Of, which is the memoir of a novelist who fears death. I read it because the quotations in reviews were very funny; because, as a fellow chronophobiac, I hoped that some wisdom and solace might be mixed in with the humor; and because I knew the author's brother Jonathan at Oxford around 1990 and wanted to understand more about this philosopher who "often wears a kind of eighteenth-century costume designed for him by his younger daughter: knee breeches, stockings, buckle shoes on the lower half; brocade waistcoat, stock, long hair tied in a bow on the upper." (This is Julian's description. I would add that the effect is less foppish that you'd think. The wearer resembles a plain-spun, serious Man of the Enlightenment much more than a dandy.)

Anyway, it's a good book and certainly amusing. But Barnes treats the most powerful consolation of morality very subtly--if he recognizes it at all. I mean the consolation of the first person plural. I will die, but we will live on. We think in both the singular and plural and probably began the former first, when we stared at our parents. Language, thought, culture, desire--everything that matters is both individual and profoundly social.

"After I die, other people will go about their ordinary lives, laughing, singing, complaining about trifles, never mourning or even missing me." That is the solipsist's jealous lament. But the mood changes as soon as the grammar shifts. "Even though I must pass, our ordinary life will continue in all its richness and pleasure."

What we count as the "we" is flexible--it can range from a dyad of lovers to the whole human race. No such "we" is guaranteed immortality. It depresses Jonathan Barnes that humanity must someday vanish along with our solar system (and we may finish ourselves off a lot faster than that). But no large collectivity of human beings is doomed to a fixed life span. We can outlive you and me, and you and I can help to make that happen. This is a consolation available to all human beings, whatever they may believe about souls and afterlives. But it is not, I think, much of a comfort to Jonathan Barnes.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:03 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 20, 2009

announcing the Summer Institute of Civic Studies

This summer, at the Jonathan M. Tisch College of Citizenship and Public Service at Tufts University, we will offer a 2-week intensive Summer Institute of Civic Studies. It is aimed mainly at PhD students from all disciplines and universities. The focus is less on my specialty--civic learning and youth civic engagement--than on what kinds of participation good societies need. Those who planned the Institute (a diverse group of scholars from around the country) have fairly strong philosophical commitments, which are summarized in this framing statement. But we will be open to all perspectives and will try to select diverse readings. The Institute will conclude with a public conference on the Obama civic agenda.

To apply to be a student, use this page. To sign up for updates, go here.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:10 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 18, 2009

the "Millennial Generation and Politics" event

C-SPAN II broadcast yesterday's event at the New America Foundation. The video is here.

Neil Howe and Reena Nadler first present their broad overview of the Millennials as a poilitical generation. I then summarize our new study that argues that (a) where a generation begins politically affects its political orientation for decades to come, and (b) the Millennials are starting more liberal than any generation for at least 40 years. (The slides from our report are a lot easier to see in the PDF). At the end, I raise some cautions about viewing the Millennials as a homogeneous group or simply comparing the average young person today to the average young person of decades past. There are enormous social and political differences among Millennials.

Scott Keeter from the Pew Research Center then makes some very astute remarks about the papers and his organization's findings. Hans Riemer, who was Obama's Youth Director in the primaries, reminisces about the campaign. (By the way, I agree with Hans that young voters won Iowa for Obama and thereby determined the election.)

In the question-and-answer, Howe and I debate a little the question of whether working-class youth fit generalizations about the Millennials as coddled, risk-averse, optimistic, high achievers. I try to emphasize that working-class youth will participate if offered constructive opportunities. There's nothing wrong with them as people. The problem is that society offers them very few opportunities to serve, lead, or create. Implicit in this mild debate is a slight difference in theoretical orientation. I believe that people in general react similarly to opportunities, but that opportunities vary with time and with socioeconomic status. I don't think of the character of a generation as an important causal factor in history, but I do recognize that different cohorts have different formative opportunities. (And opportunities always vary for people who happen to be born at the same time.) As an example, I don't believe that my generation--Generation X--has failed to obtain political office because we always lacked intrinsic interest or commitment. Many of my Yale college classmates wanted political careers desperately. I think we lacked opportunity in an era of gerrymandered electoral districts and out-of-control campaign spending.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:17 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

fundamental orientations to reform

(This is a rambling post written during a flight delay at Washington National. It lacks an engaging lead. In brief, I was thinking about various conservative objections to utopian reform and how social movements, such as the Civil Rights Movement, can address some of those objections.)

The French and Russian revolutions sought dramatically different objectives--the French Jacobins, for example, were fanatical proponents of private property--but they and their numerous imitators have been alike in one crucial way. Each wave of revolutionaries has considered certain principles to be universal and essential. They have observed a vast gap between social reality and their favored principles. They have been willing to seize the power of the state to close this gap. Even non-violent and non-revolutionary social reformers have often shared this orientation.

I see modern conservatism as a critique of such ambitions. Sometimes the critique is directed at the principles embodied in a specific revolution or reform movement. The validity of that critique depends on the principles in question. For example, the Soviet revolution and the New Deal had diametrically opposed ideas about individual liberty. One could consistently oppose one ideology and support the other.

Just as important is the conservative's skepticism about the very effort to bring social reality into harmony with abstract principles (any principles). Conservatives argue: Regardless of their initial motivations, reformers who gain plenipotentiary power inevitably turn corrupt. No central authority has enough information or insight to predict and plan a whole society. The Law of Uninintended Consequences always applies. There are many valid principles in the world, and they trade off. The cost of shifting from one social state or path to another generally outweighs the gains. Traditions embody experience and negotiation and usually work better than any plan cooked up quickly by a few leaders.

These are points made variously by Edmund Burke, Joseph de Maitre, James Madison, Lord Acton, Friedrich von Hayek, Isaiah Berlin, Karl Popper, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, and James C. Scott, among others: a highly diverse group that includes writers generally known as "liberals." But I see their skepticism about radical reform as emblematic of conservative thought.

Two different conclusions can follow from their conservative premises. One is that the state is especially problematic. It monopolizes violence and imposes uniform plans on complex societies. Its power reduces individual liberty. Individuals plan better than the state because they know their own interests and situations, and they need only consider their own narrow spheres. They have limited scope for corruption and tyranny. Therefore the aggregate decisions of individuals are better than the centralized rule of a government. This is conservative libertarianism: the law-and-economics "classical liberalism" of Hayek, not the utopian libertarianism of Ayn Rand or Robert Nozick (as different as those authors were).

The alternative conclusion is that local traditions should generally be respected. Reform is sometimes possible, but it should be gradual, generally consensual, and modest. The odds are against any effort to overturn the status quo, imperfect as that may be. This is Burkean traditionalist conservatism. The Republican Party has very little interest in it today, but it motivates crunchy leftists who prize indigenous customs and cultures and oppose "neo-imperialism" (just as Burke opposed literal imperialism).

These two strands of conservative thought often come into conflict, because actually existing societies do not maximize individual liberty or minimize the role of the state (or of state-like actors, such as public schools, religious courts, clans, and bureaucratic corporations). Traditionalists and libertarians disagree forcefully about what to do about illiberal societies.

Take the case of Iraq under Saddam. The so-called neoconservatives (actually libertarians of a peculiar type) claimed that the main problem with Iraq was a tyrannical state, and the best solution was to invade, liberate, and then constrain the successor regime sharply. Private Iraqis should govern their own affairs under a liberal constitution. The Burkean response was that Iraq was a predominantly non-liberal society, deeply religious and patriarchal; therefore, a liberal constitution would be an alien, utopian imposition that would never work.

We can envision a kind of triangular argument among utopian revolutionaries, Burkean traditionalists, and libertarians--with strengths and weaknesses on all sides. But there is a fourth way. That is the deliberately self-limiting utopian social movement. The Gandhian struggle in India, the Civil Rights Movement in the United States, and the anti-Apartheid movement in South Africa shared the following features: (1) regular invocation of utopian principles, portrayed as moral absolutes and as pressing imperatives; (2) deep respect for local cultures, traditions, and faiths; (3) pluralism and coalition politics, rather than a centralized structure; and (4) strict, self-imposed limits.

The South African ANC had a military wing that aimed to capture the state, whereas Gandhi and the Civil Rights Movement were non-violent. But I would describe non-violence as simply an example of a self-limitation designed to prevent corruption and tyranny. It's a good strategy, because violence tends to spin out of control, to the detriment of the reformers themselves. But it isn't intrinsically or inevitably better than other strategies. The ANC managed to use violence but to restrain itself--as did the American revolutionaries of our founding era.

So now we see a four-way debate among utopian reformers, libertarians, traditionalists, and social-movement reformers. Social movements have answers to several of the chief arguments made by the other sides. They can address conservative worries about arrogance, corruption, and tyranny while also seeking to change the world in principled ways. The problem for social movements is institutionalization. Such movements tend to crest and then fall away, unlike the regimes that the other ideologies promote.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:02 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

February 17, 2009

thoughts on Hugo Chavez

After President Chavez of Venezuela won the right to seek perpetual reelection, it occurred to me that:

1. Venezuela poses no risk to the United States. Its government must sell oil on the international market or it will collapse economically. If Chavez decides not to sell to us, we can still buy oil at the global price: it's a commodity. Leaving aside short-term psychological shocks from a Venezuelan embargo, they have little power to affect world prices. They can use their oil revenues to fund overseas military adventures, but their military options are limited. Because Venezuela does not threaten us, we have limited standing to try to influence that country. However ...

2. Chavez is almost certainly moving in exactly the opposite direction from what we need in the 21st century. He is centralizing power in the national government; merging military, administrative, and partisan-political authority; combining personal macho charisma with media celebrity and formal power; reducing political pluralism, checks-and-balances, and civil liberties; exploiting fossil fuels to the maximum; monopolizing the market, press, and state sectors; and trying to exacerbate the deep tensions in Venezuelan society instead of helping everyone to work together. I'd recommend a 180-degree different course. But ...

3. Chavez occupies a huge and growing political niche. It is remarkable, in a world where about one billion people live on less than $1 per day, one quarter of children in developing countries are underweight because of inadequate food, and one quarter of children in the same countries are not in school, that there isn't a more active and aggressive political movement that demands urgent economic redistribution.

I would generally favor moderate and market-based solutions to poverty, but the credibility of the market must surely suffer now that Wall Street and the City of London have been shown to be incapable of managing even their own affairs. I think there would already be a much more robust global radical left if we hadn't just passed through the long aftermath of the Soviet fiasco. Russian Communists first eliminated many rivals on the left and then collapsed, leaving a remarkable void. If Intel and Microsoft suddenly went bankrupt, there would be a lot fewer new computers in production next year. But the computer industry would revive to meet the demand, and the same thing will happen with the redistributionist left.

Thus for me the interesting question is to what extent Chavez (and Evo Morales, and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad) will fill the political niche of opposition to global capitalism. From my own biased perspective, it seems much better if someone like President "Lula" da Silva of Brazil can obtain international leadership. In fact, I'd love to see the Obama administration take thoughtful and effective steps to build Lula up--not in our interests so much as the interests of the Global South.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:10 PM | Comments (3) | TrackBack

February 16, 2009

national service in the stimulus

The final stimulus bill that the president will sign on Tuesday includes $201 million for AmeriCorps, an increase of roughly one fourth. I don't know whether positions in AmeriCorps programs count as "jobs" and will thus help the president to meet his target of four million jobs created or preserved. At $10,900 for a year's work, the AmeriCorps stipend is low--as pay. But I would justify putting this item in the stimulus because thousands of young people are missing the educational advantages of work now that the youth unemployment rate is above 21%. AmeriCorps programs provide generally good experiential education in the form of work-like positions that are challenging and inspiring. They can thereby partially compensate for a lack of jobs.

Shirley Sagawa and others are correct that the best measure of AmeriCorps is quality, not quantity. It matters how much participants learn and achieve, not only how many people participate. But I think the quality is high enough today that the $201 million will be well spent.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:14 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 13, 2009

new paper, and event, on the Millennials and politics

My colleagues Connie Flanagan and Les Gallay and I have a new paper about the Millennials' political orientation. It is, I believe, the first paper that traces the political evolution of several past generations in order to see whether there is a typical pattern over people's lifetimes. We find that there is a typical trajectory of political opinion. On this basis, we predict that the Millennials will put a distinctive stamp on American politics for decades to come. The paper is already online (PDF). It will be released formally and discussed next Wednesday in Washington.

The event is entitled "The Latest Generation: The Unique Outlook of "Millennials" and How They Will Reshape America." Speakers will include Neil Howe, Reena Nadler, and yours truly. Scott Keeter, Director of Survey Research at Pew Research Center, and Hans Riemer, National Youth Vote Director for the Obama campaign and former Political and Issues Director for Rock the Vote will comment.

Posted by peterlevine at 2:56 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

February 12, 2009

public engagement in the stimulus: Virginia's example

In a comment yesterday, Michael Weiksner argued for more public voice in the allocation of stimulus funds. Experiments from around the world have found that public involvement in public-sector spending decisions improves the quality of those decisions and reduces corruption during the implementation phase. If, for instance, citizens help to decide that a school should be built at a particular location, they are likely to make sure that it is built well, on budget and on schedule.

I've argued that the federal government should take the lead in encouraging public voice; that should be a top priority of the new White House office on civic engagement. But it's also possible to introduce public participation further downstream. Virginia has launched an official website to collect public ideas on how to spend that state's federal money. Ideally, the site will turn into more than a list of suggestions, with perhaps an opportunity for voting. There should also be ways for people to add value to suggestions, wiki-style.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:28 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 11, 2009

Krugman v Obama

I think Paul Krugman's critiques of Barack Obama (starting early in the primary season and continuing today) represent one of the most interesting debates in American politics. Here's a simplified version:

- Krugman: The problem with America is conservatism, which is wrong and bad. A failed conservative president represented a golden opportunity to make the anti-conservative case in a way that would permanently change American politics. This argument had to be made forcefully, without rhetorical compromise or nuance. The Republicans had to be sent packing, with Bush hung around their necks.

Obama: The problem with America is a set of poor relationships--relationships among citizens, between the public and the government, and between America and other countries--that make good governance impossible. The Bush disaster happened because of public alienation, low expectations, polarization, and a neglect of shared values. There are many reasons for public distrust of government. Poor performance is one. Another is that half of our representatives in Washington keep saying that the other half are crooked and idiotic, and then the other half says the same back. To rebuild essential relationships will require dialog and civility.

Now Krugman says that the stimulus plan is too small, and the cuts engineered by "centrist" Senators have made it worse. "But how did this happen? I blame President Obama’s belief that he can transcend the partisan divide--a belief that warped his economic strategy."

The stakes are as high as can be, and if Krugman is correct, Obama's whole "theory of change" is badly flawed.

We don't really know how big a stimulus is big enough, but when a Nobel prize-winner says that $800 billion is too small, who am I to argue? What I would question is Krugman's political explanation for how that number arose. Obama annoyed Krugman by meeting with Republicans and conservatives, acting respectfully toward them, and appearing to welcome negotiation. I think that behavior was completely unrelated to the outcome of the bargaining in Congress. The Administration could have proposed a $1.2 trillion stimulus, followed by much respectful listening and negotiation. The result would have been a $1 trillion package--more acceptable to Krugman the economist (but perhaps just as annoying to Krugman the political strategist). Instead, the Administration started lower and ended at around $800 billion. I doubt very much that they chose their original number because they thought it would encourage dialog and civility. Economic and administrative considerations must have determined that initial number. Perhaps it was too low, but that had nothing to do with Obama's style of interaction after he put a bid on the table.

As I've written several times before, it is not just the editorial board of the Washington Post that likes bipartisanship. The public likes it, and that shows in Obama's stratospheric popularity right now. People think that he's trying to deliberate. Once he tries to talk, he's free to criticize the opposition. That's not merely a clever strategy,; it's also good manners.

Obviously, being popular is not an end in itself. But the public will oppose government spending unless they respect the people in charge of the government; and comity is the path to respectability.

Here's what I'm left unsure of. Presuming that $800 billion is too little money, which of the following is true?

- 1. For psychological reasons--to break the cycle of recession--it's necessary to spend enough money in one initial bang. $800 billion isn't enough, so the recession will worsen. The government will spend more, but too late. Obama will govern for four years of deep pain and will be unable to achieve any substantive domestic reforms.

-- or --

2. The government cannot do a good job passing and implementing legislation that costs more than $800 billion. (Even that amount is a major stretch.) But they can spend more later, including another big dose for health care reform. To be sure, the legislative rules regarding how deficits are "scored" will change after the stimulus passes; but rules can be changed again. As long as the total amount spent in FY 09 and FY 10 is sufficient, it's better to do it more deliberately and in a spirit of maximum comity that the American people admire.

I obviously hope that #2 is correct, but #1 could be better economics.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:00 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

February 10, 2009

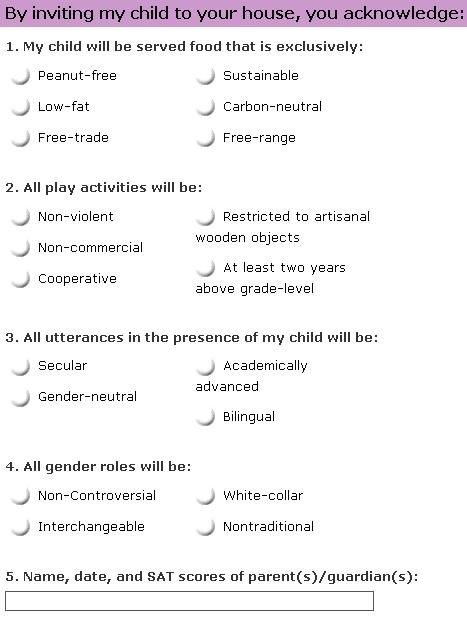

a "play date" release form for the use of anxious and busy parents

Posted by peterlevine at 9:18 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 9, 2009

Elinor Ostrom speaking at Tufts

Please join us...

The Drama of the Commons: What Makes Cooperation Work

Elinor Ostrom will receive the 2009 Jonathan M. Tisch Prize for Research on Civic Engagement and discuss citizenship, civil society, and the civic role of universities. I will interview her publicly and then open the discussion to the audience.

March 5, 2009

3:30pm – 5:00 pm

Crane Room, Paige Hall

Tufts University

Reception to follow, 5:00-7:00

Rabb Room, Lincoln Filene Hall

No RSVP necessary

Elinor Ostrom is Arthur F. Bentley Professor of Political Science at the University of Indiana. Her work concerns collective decisions and voluntary cooperation. In laboratory experiments, she studies when and how human beings cooperate. As a formal theorist, she has contributed essential insights to our understanding of collective action and collective choice. She has also collaborated with and advised nonprofit organizations in many countries as they address practical issues. These collaborations have enriched her formal theory and her scientific research. She has founded and directed institutes that combine theory, empirical research, practice, and the analysis of policy. The contexts of her research have ranged from traditional agricultural practices to policing in urban America to the Internet as a “commons.” As a teacher, a college administrator, and a leader of institutions, she has been a civic educator and has advocated for civic education. She is a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and former president of both the American Political Science Association and the Midwest Political Science Association.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:26 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 6, 2009

free advice

My childhood friend Chris Kutz, now a law professor at Berkeley, has organized a blog that consists only of policy proposals by Cal colleagues, including several famous professors. It's called Blue Sky: New Ideas for the Obama Administration. Here is an op-ed in the San Francisco Chronicle that announces it.

Meanwhile, Tufts University, where I work, has a webpage entitled "Memo to the President: Faculty weigh in with advice for Barack Obama as he begins his term." It's not a blog, but each professor contributes a few paragraphs that remind me of blog posts.

These pages make me wonder ...

- How many other institutions are also organizing their faculty to write short public memos for the new president?

- Is there much more of this in 2008 than ever before? (So it seems to me, but I could have missed such sites in 2000 and 2004.)

- If so, what's the stimulus? I can imagine that more faculty admire Obama than have liked any president in my adult lifetime; that blogging has made professors more prone to write and publicly post short opinion pieces; and that the Presidential Transition Team prompted people to write this sort of statement by inviting comments on change.gov. Those are hypotheses; I don't know the real story.

- Assuming that this kind of site is a common development, what does it mean? Is it a sign of productive faculty engagement in public life? A welcome turn to transparency (since earlier generations of faculty would have sent private letters to the president)? A rather quixotic or naive activity? Or a sign of professorial arrogance? I am personally enthusiastic, but this seems a worthy topic of discussion.

- What will happen after the new administration settles in? Will this kind of activity continue, or turn into something different, or go away?

Posted by peterlevine at 1:42 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 5, 2009

the Boston community mapping project

This little presentation describes our software for mapping a community, and our progress in using it so far in the Boston area.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:16 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 4, 2009

most people aren't going to college

Reporters and others consistently equate youth with college students. Going to college is treated as the norm, and those who don't enroll are seen as some kind of exceptional minority that needs help with "college access." I've also heard the argument that college is the best time to develop civic and ethical skills and values.

It is therefore essential to understand that most young adults do not attend college, even 2-year or community college. The norm is to finish one's education at high school. Nor have rates of college attendance budged upward for decades. CIRCLE's fact sheet (PDF) shows the flat trend:

Another way to show the current situation comes from a new Bureau of Labor Statistics report (pdf), which uses the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997, "a nationally representative survey of about 9,000 young men and women who were born during the years 1980 to 1984." This is my graph derived from that report:

It shows that during the traditional "college years" (ages 18-21), the proportion of young adults who are actually in college never reaches 40%. To be sure, some of the others will obtain college credits--and even bachelors degrees--during their lifetimes. (The fact that you can attend college at any point makes it hard to say what the college matriculation and graduation rates are for a given generation--we only really know after they all die.) But it's clear that the norm is not to go to college when one is of conventional "college age."

I'm in favor of getting more young adults on a college path, to the extent that's possible. But we are nowhere close to enrolling everyone, and it's not obvious that that would even make economic sense. Thus it is essential not to reserve enriching, rewarding, and remunerative opportunities for the minority of people who go to college. We also need to watch our language and our assumptions--"youth" doesn't mean "college student," and college attendance is not (in any sense) the norm.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:26 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 3, 2009

Aert de Gelder, "Rest on the Flight to Egypt"

This painting, from about 1690, is one of my favorites in our new home town of Boston. (It's in the Museum of Fine Arts.) The "Rest on the Flight to Egypt" is an old subject for paintings, going back to the middle ages. It illustrates Matthew 2:12-14:

- And being warned of God in a dream that they should not return to Herod, they departed into their own country another way. And when they were departed, behold, the angel of the Lord appeareth to Joseph in a dream, saying, Arise, and take the young child and his mother, and flee into Egypt, and be thou there until I bring thee word: for Herod will seek the young child to destroy him. When he arose, he took the young child and his mother by night, and departed into Egypt.

For some reason that I don't know, artists have (for many centuries) chosen to depict the little family pausing on the way to Egypt. That makes an acceptable subject for a Protestant, because it's a "history painting"--an illustration of something that really happened, according to the Bible. In contrast, a painting of the "Holy Family" or the "Virgin and Child with Saints" would be problematic from a Protestant perspective. Those extremely common subjects developed as Orthodox and Catholic devotional objects, as icons or stimuli to prayer and meditation. For Protestants, they verge on "graven images."

De Gelder (a student of Rembrandt) was a Protestant, but he has found a way here to imitate a "Holy Family" or a "Madonna and Child with Saint." Joseph resembles St. Jerome in a painting of a sacra conversazione. And (as my wife Laura notes) the Madonna's halo has migrated onto Mary's extraordinary circular, gold-rimmed hat.

I take no sides in the Protestant/Catholic debate about religious images. But I think the shift from a Madonna and Child to a history painting has produced wonderful effects in this particular work. Since the baby is not an object of veneration, he can act like a real infant--snuggling down into his mother's lap instead of being displayed upright. Joseph reads a grown-up book, presumably for the edification of the adults in the family--but he pauses to gaze affectionately at his newborn (holding his place with his finger). It's an affectionate representation of a human family, with subtle echoes of the grand Catholic tradition.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:23 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack