« December 2007 | Main | February 2008 »

January 31, 2008

from TIME's story on the "year of the youth vote"

(Tampa) These are helpful statistics. They put into numbers what we can feel experientially: an enormous increase in the proportion of young Americans who are paying attention to the election this year. (Also, a very steep tilt toward the Democratic candidates.) The full story is here.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:26 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

January 30, 2008

to Tampa

If this page is going to remain a blog, I need to return sooner or later to daily posting. Right now, I'm heading to Tampa, Florida, where the Hillsborough County Schools are launching a major initiative to teach students about democracy and citizenship. They won a highly competitive $2 million federal grant for that purpose. I'm going to participate in a televised discussion at 10:30 tomorrow morning with the Mayor, Pam Iorio, who is planning to create a youth commission. Then I'm having lunch at the University of South Florida with an interdisciplinary group of professors who are active in community service and research. At 5 pm, I'm giving a keynote speech at Freedom High School to help kick off the county's program.

Posted by peterlevine at 4:03 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

January 26, 2008

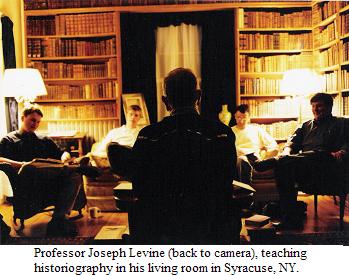

Joseph M. Levine

(Syracuse, NY) My Dad, Joe Levine, died at 6:50 am today after a long struggle with cancer that gave him many trials and indignities. I have some misgivings about using a blog to write about his death. Even the word "blog" seems unworthy of the occasion, which should be observed privately by those who knew and loved him or else in some serious professional setting such as an obituary or an academic memorial service. Indeed, we hope to achieve all of those things, but I cannot resist using this space for at least for a few quick notes.

Dad was best as a husband and father. Those were the roles he cared about most and performed with the most commitment and distinction, especially for a man of his generation. He took advantage of the flexibility of an academic career to spend immense amounts of time with his family. I think he almost always preferred to be with all of us, or--if his children were unavailable--at least to be alone with Mom, his partner of 52 years. We gamely accompanied him to chamber music concerts, used bookstores, and auctions, and he came along with us to playgrounds and shopping malls. He also walked us to school when we didn't want to go (a feeling he remembered from his own childhood) and sat up with us when we couldn't sleep. He was a peaceful, gentle man and he shed peace on his family and friends.

As Joseph M. Levine, Dad was Distinguished Professor of History at Syracuse University, where he taught from 1966 until a few weeks ago. He was "distinguished" in more than title, having built an international reputation as a historian of ideas and a cultural historian. Anthony Grafton, the Henry Putnam University Professor of History at Princeton and vir eruditissimus, has called him "one of the most distinguished intellectual historians in the English-speaking world." Indeed, he was the world's leading authority on how the British understood and practiced history from the Renaissance to the eighteenth century. I need hardly say that this is an important topic because a culture's understanding of history is fundamental to its development.

Dad published six books and many articles. In Doctor Woodward's Shield (1977; second edition, 1991), he recovered the spirit of English intellectual life around 1700 by telling the story of a controversy that involved many of the leading wits, scholars, and scientists of the era. (The controversy concerned a shield that was thought to have belonged to Achilles himself, but ultimately turned out to be a forgery). The London Review of Books called Dr. Woodward's Shield "one of the most imaginative contributions to the history of ideas written in the last fifty years." In The Battle of the Books: History and Literature in the Augustan Age (1991) and in Between the Ancients and the Moderns: Baroque Culture in Restoration England (1999), Dad described the dispute about whether ancient culture was always superior to modern culture: an argument that profoundly influenced writers, scholars, scientists, and artists for several centuries. In The Autonomy of History: Truth and Method from Erasmus to Gibbon (1999), and in other writing throughout his career, Dad described the development of historical thinking and methodology. He was a passionate defender and teacher of the modern methods and craft of history, even though he was most widely read in departments of English and art history.

It is a paradox about Dad that he relished arguments and disputes, which provided the material for all his writing and which always piqued his interest, yet everyone who knew him would describe him as gentle. He argued against ideas, not against people. He was especially good, in fact, at seeing why people might adopt ideas with which he disagreed. That is a great asset for a cultural or intellectual historian.

Throughout his career, Dad was concerned with such questions as: How did history separate itself from fiction? Why was the imitation of classical models so popular and successful for several centuries of European history, and then what reduced the impulse to imitate Rome and Greece? How and why did modern methods of historical research develop? When and why did Europeans begin to understand ancient culture as profoundly different from their own? He always approached such questions by identifying particular people who had thought and written about historical issues (usually in disputes with others). He sought to recover their original motives and reasons through meticulous research, based on primary sources. This was the historical method whose development he traced back to the Renaissance.

Although he was an historian of ideas, Dad was profoundly an empiricist. He believed that ideas arose more or less the same way that other events occurred: because of the choices people made for particular purposes in local circumstances. His empiricism was a high principle that he defended, for instance, in a significant critique of the political theorist Quentin Skinner. But I think Dad was an empiricist in a much more fundamental and instinctive sense. He simply loved to poke around, to explore, to uncover unexpected facts even if they disrupted his own theories. The same man who haunted bookstores, snapped photos of sculptures in obscure European cities, drove around Upstate New York looking for antiques, and tried one minor Baroque composer after another was also a man who made his scholarly career by browsing. He browsed through the tangled narratives of forgotten disputes because he loved to be lost in facts.

Dad was born in Brooklyn, NY in 1933 and grew up near Ebbetts Field. He was very much a Brooklyn Jew: unobservant (indeed, unbelieving), but proud of his heritage and very much a product of it. He was perhaps a little unusual for a Brooklynite in that he became quite an Anglophile. Our family always took its bearings from early-modern English culture, and more broadly, from the Christian civilizations of the Atlantic nations of Europe. Central and Eastern Europe, from which Dad's family had come, were in his distant periphery; Israel mostly exasperated him. He knew French and Italian but basically no German or Hebrew. Nevertheless, I think Dad took a dose of Germanic culture from the emigré scholars who had transformed American universities during and after the War. They believed that one could gain spiritual or moral freedom by appreciating very fine works of culture; and that one could best appreciate a cultural object by understanding its social context, which required scholarship. The classicist Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Mollendorf, who epitomized the German academy around 1900, wrote, "aesthetic evaluation is possible only from the perspective of the time in which the artwork was situated, out of the spirit of the people which brought it forth." Add to that doctrine the Kantian idea that aesthetic evaluation develops character and freedom, and you can see why a person might study and collect books, prints, and records and write and teach about subjects like humanism and classicism. You can also see why Dad treated scholars like Arnaldo Momigliano, Erwin Panofsky, and Erich Auerbach with such profound respect.

But to mention such influences is to overlook Dad's passionate connection to the United States. He chose to spend years in England and elsewhere in Western Europe, but there was no question that he was an American. In fact, he was interested in English intellectual history up to the 18th century as the main precursor of American thought. Dad rooted for the Jets, the Mets, and the Democrats through thick and thin. He appreciated the dynamism of the United States and some (but by no means all) of its latest trends. I connect him especially to the everyday culture of New York City from the thirties to the sixties: the mix of people on the streets, the accents, the Subway, the bookstores on Fourth Avenue, the Brooklyn Dodgers, the bars in Morningside Heights, racks of used classical LPs, hot dogs from stands, the ideals and public institutions of La Guardia and FDR.

Dad graduated from Stuyvesant High School in New York City and then from Cornell University. He received a PhD in history from Columbia in 1965 after quite a long period as a part-time professor and active New Yorker. (He and Mom even worked on turning Ellis Island into a college; they were always, in my jargon, "civically engaged.") After some short stints at other institutions, Dad moved to Syracuse University and soon rented--later owned--the house where I grew up and where he died.

Although they were based in Syracuse, my parents spent more than 35 summers and several full years in England, where Dad used the historical archives and acquired most of his 30,000 books, especially the old ones. One year, he shipped home an actual ton of books. At first, my parents rented a different home in England on almost every annual visit. Recently, they have owned a tiny house in Camden Town from which they could walk together to the British Library. Although they cherish some English friends, their main social circle over there consists of American academics (mainly, Jewish New York academics) who use the British archives.

Disease made the last years hard for Dad, but they were definitely not without compensations. He especially enjoyed his grandchildren and had some time for teaching and travel even after he was diagnosed with cancer. Near the end, the disease struck hard at his mind and dignity. However, I recall one moment from recent weeks that was still very characteristic of him. We were visiting a cancer-care facility that offered a high-tech treatment. It was a very commercial place; we ultimately found we couldn't afford the technology they pushed. The first person who spoke to us was the "patient advocate"--a corporate euphemism for the official who tried to sign us up as clients. She said that she had studied some history but had dropped it when it turned out there were no teaching jobs in her local school district. Dad could have been put off by the whole experience. Instead, he remarked, "What a great country, that it throws up so many confident young women like that. Not long ago, all those jobs were filled by men." I thought that remark perfectly captured Dad's humane and liberal generosity. The same spirit also determined his views on race, class, education, and civil liberties.

One dark recent night as Dad (delirious) and I (despairing) sat together in his study, which is lined with books about historians, I found and silently read the following text. The great historian Marc Bloch joined the French Resistance and was tortured and killed by the Gestapo. He left this testament (translated by Gerard Hopkins):

When death comes to me, whether in France or abroad, I leave it to my dear wife or, failing her, to my children, to arrange for such burial as may seem best to them. I wish the burial to be a civil one only. The members of my family know that I could accept no other kind. But when the moment comes I should like some friend to take upon himself the task of reading the following words ...:I have not asked to have read above my body those Jewish prayers to the cadence of which so many of my ancestors, including my father, were laid to rest. All my life I have striven to achieve complete sincerity in word and thought. I hold that any compromise with untruth, no matter what the pretext, is the mark of a human soul's ultimate corruption. Following in this a much greater man than I could ever hope to be [I think the reference is to Ernest Renan], I wish for no better epitaph than these simple words:--DILEXIT VERITATEM [he loved the truth]. That is why I find it impossible, at this moment of my last farewell, when, if ever, a man should be true to himself, to authorize any use of those formulae of an orthodoxy to the beliefs of which I have ever refused to subscribe.

But I should hate to think that anyone might read into this statement of personal integrity even the remotest approximation to a coward's denial. I am prepared therefore, if necessary, to affirm here, in the face of death, that I was born a Jew: that I have never denied it, nor ever been tempted to do so. In a world assailed by the most appalling barbarism, is not that generous tradition of the Hebrew Prophets, which Christianity at its highest and noblest took over and expanded, one of the best justifications we can have for living, believing, and fighting? A stranger to all credal dogmas, as to all pretended community of life and spirit based on race, I have, through life, felt that I was above all, and quite simply, a Frenchman. A family tradition, already of long date, has bound me firmly to my country. I have found nourishment in her spiritual heritage and in her history. I can, indeed, think of no other land in which I could have breathed with such air and freedom. I have loved her greatly and served her with all my strength. I have never found that the fact of being a Jew has at all hindered these sentiments. Though I have fought in two wars, it has not fallen to my lot to die for France. But I can, at least, in all sincerity, declare that I die now, as I have lived, a good Frenchman.

If we substitute "America" for "France," add gentleness and tact to Bloch's cardinal virtue of sincerity, and delete the sentence about serving in two wars, these words would beautifully and precisely describe my father.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:48 AM | Comments (6) | TrackBack

January 25, 2008

vigil

(Syracuse) I haven't wanted to post here because I have been helping to care for my Dad at the very end of his good life. I have an appreciation of him written and ready to post when his struggle finally does end.

Posted by peterlevine at 3:09 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

January 18, 2008

on shared responsibility for private loss

(Syracuse, NY) Yesterday, I wrote a fairly frivolous post in response to Steven Landburg's New York Times op-ed, because I found one of his analogies risible. But I suppose it's worth summarizing the standard serious, philosophical argument against his position (which is libertarian, in the tradition of Robert Nozick). Lansburg asks whether we should compensate workers who would be better off without particular free-trade agreements that have exposed them to competition and have thereby cost them their jobs.

One way to think about that is to ask what your moral instincts tell you in analogous situations. Suppose, after years of buying shampoo at your local pharmacy, you discover you can order the same shampoo for less money on the Web. Do you have an obligation to compensate your pharmacist? If you move to a cheaper apartment, should you compensate your landlord? When you eat at McDonald’s, should you compensate the owners of the diner next door? Public policy should not be designed to advance moral instincts that we all reject every day of our lives.

I need not compensate a pharmacist if I buy cheaper shampoo than she sells, because I have a right to my money, just as she has a right to her shampoo. We presume that the distribution of property and rights to me and to the pharmacist is just. We're then entitled to do what we want with what we privately own. But who says that the distribution of goods and rights on the planet as a whole is just? It arose partly from free exchanges and voluntary labor--and partly from armed conquest, chattel slavery, and enormous helpings of luck. For example, some people are born to 12-year-old mothers who are addicted to crack, while others are born to Harvard graduates.

Given the distribution of goods and rights that existed yesterday, if we let free trade play out, some will become much better off and some will become at least somewhat worse off as a result of voluntary exchanges. Landsburg treats the status quo as legitimate--or given--and will permit it to evolve only as a result of private choices (which depend on prior circumstances). However, the Constitution describes the United States as an association that promotes "the general Welfare." Within such an association, it is surely legitimate for people who are becoming worse off to state their own interests, and it is morally appropriate for others to do something to help. (How much they should do, and at what cost to themselves, is a subtler question.)

Of course, one can question the legitimacy of the American Republic. It is not really a voluntary association, because babies who are born here are not asked whether they want to join. And its borders are arbitrary. That said, one can also question the legitimacy of our system of international trade. It is based on currencies, corporations, and other artificial institutions.

The nub of the matter is whether you think that individuals may promote their own interests in the market, in the political arena, or both. If one presumes that the economic status quo is legitimate, then the market appears better, because it is driven by voluntary choice. But if one doubts the legitimacy of the current distribution of goods and rights, then politics becomes an attractive means to improve matters. Because almost all Americans believe in the right and duty of the government to promote the general welfare, even conservatives like "Mitt Romney and John McCain [battle] over what the government owes to workers who lose their jobs because of the foreign competition unleashed by free trade."

Posted by peterlevine at 2:16 PM | Comments (3) | TrackBack

January 17, 2008

the dismal science

Steven E. Lansburg in yesterday's New York Times:

Even if you’ve just lost your job, there’s something fundamentally churlish about blaming the very phenomenon that’s elevated you above the subsistence level since the day you were born. If the world owes you compensation for enduring the downside of trade, what do you owe the world for enjoying the upside?

This gives me great ideas for other moral arguments! For example,

It is churlish for people to complain and whine when they're drowning. They were happy enough to drink water earlier in their lives. Their bodies are mostly made of water, for crying out loud.

Or:

Can you believe how people don't want to get shot? Don't they realize that our forefathers used bullets to shoot the Redcoats and win our freedom? Where would we be today without gun-related deaths?

Or:

Americans nowadays seem to want medicine whenever they get sick! Can you believe it? Don't they realize that without plagues and pestilence, Europeans would never have conquered the New World?

Posted by peterlevine at 10:23 AM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

January 16, 2008

the presidential candidates on community and national service

Courtesy of the National Service-Learning Partnership, here is a chart showing the presidential candidates' positions on AmeriCorps, community service and service-learning in schools, student loans in return for community service, and related issues. Some highlights: Chris Dodd would have required 100 hours of service for high school graduation across the nation (which would be a very controversial federal mandate). John Edwards would create a new Community Corps and reward schools that require service for graduation. Hillary Clinton co-sponsored the Public Service Academy Act to create a new academy in Washington, DC that would prepare people for civilian service. Mike Huckabee would expand civilian national service; and John McCain has a record of supporting AmeriCorps. I have written before about Barack Obama's ambitious plan.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:56 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

January 15, 2008

the legacy of the Civil Rights Movement

I have some reflections on the recent spat between Senators Clinton and Obama, but first, here is the actual "text" of their dispute as accurately as I can capture it.

At the Democratic Debate in New Hampshire, Senator Clinton said: "So, you know, I think it is clear that what we need is somebody who can deliver change. And we don't need to be raising the false hopes of our country about what can be delivered. The best way to know what change I will produce is to look at the changes that I've already made."Back on the trail, Senator Obama said, "For many months I've been teased, almost derided, for talking about hope ... We saw it in the debate last night. One of my opponents said, 'We can't just offer the American people false hopes of what we can get done.' False hopes!" Later, in Labanon, NH, he amplified his position: "Dr. King standing on the steps at the Lincoln Memorial, looking out over that magnificent crowd, the Reflecting Pool, the Washington Monument: 'Sorry, guys. False hope. The dream will die. It can't be done.' "

Then, on Fox News, Major Garrett asked Senator Clinton if she would respond to Senator Obama, and she said, 'I would, and I would point to the fact that that Dr. King's dream began to be realized when President Lyndon Johnson passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, when he was able to get through Congress something that President Kennedy was hopeful to do, the president before had not even tried, but it took a president to get it done. That dream became a reality. The power of that dream became real in people's lives because we had a president who said, 'We are going to do it,' and actually got it accomplished."

During and after this exchange, the candidates, their surrogates, and pundits have said many things that do not deserve to be taken seriously or at face value. But I thought the comments themselves raised valid and relevant issues about how major social change is accomplished.

For the sake of simplicity, we might say that there were three great reasons for the civil rights reforms of the 1960s: (1) The charismatic leadership of people like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and his colleagues and rivals; (2) the skillful political maneuvering of politicians like Lyndon Johnson; and (3) the great popular movement that arose from grassroots voluntary institutions, especially Black churches.

If we interpret Senator Clinton charitably, I think she was saying that Democrats are at risk of voting for charisma (Senator Obama) without realizing that you also need the skills, tactics, and experience of professionals like Lyndon Johnson--and by analogy, herself. Other critics of Senator Obama also believe that what he basically offers is charisma. For instance, Paul Krugman has recently written, "The Democrats in general make far more sense [about Chinese trade policy]. But among at least some of Barack Obama's supporters there seems to be a belief that if their candidate is elected, the world's problems will melt away in the face of his multicultural charisma." I thought that Krugman created a straw man; but it's true that charisma is inadequate and voters should pause before voting for the candidate who happens to be the best speaker.

Clearly, the third ingredient of the civil rights movement--neither political tactics nor charismatic leadership, but grassroots organizing--was crucial to its success. Senator Obama might have emphasized that point in his response to Senator Clinton (instead of attacking her for besmirching the sainted memory of Dr. King). In fact, at his next opportunity to speak after Senator Clinton talked about "false hopes" in the debate, Senator Obama said, "And just to wrap up, part of the change that's desperately needed is to enlist the American people in the process of self-government." He could have amplified that point over the succeeding days and noted that Lyndon Johnson couldn't have done a thing without active pressure from citizens. He could have used language like Rich Harwood's: "No candidate, no matter how gifted or skilled, can through their campaign offer redemption to a nation on its stained history. Surely, the candidate can help lead and give voice to such a process, but the great work of coming together will ultimately only occur through the efforts of people in their communities, and only over time."

Alas, we do not have large, highly active, interlinked progressive organizations that are rooted in the working class, as we did from 1930s through the 1960s. A pessimist might say: Therefore, the best we can get is whatever skilled political tacticians can win by playing the Washington game effectively. The question is who's the most skillful tactician in the race? (I'm not actually sure of the answer, because none of the three leading Democrats has a legislative record even close to LBJ's.)

An optimist would say: There are pieces of a civic infrastructure in America, and innovative ways for citizens to engage. The right kind of national leader can strengthen that infrastructure by encouraging active citizenship rhetorically and by implementing policies that get ordinary people more involved. The first step is to change the debate we have seen over the last few days. It should not be about who supports civil rights policies, nor about who respects Martin Luther King. It should be about how to achieve positive social change.

Posted by peterlevine at 5:55 PM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

January 14, 2008

citizens at work

(Syracuse Airport) Public Agenda's president, Ruth Wooden, writes, "Neither Third-Party Candidate nor Leadership Alone Can Solve the Problem." The "problem" that she has in mind is destructive partisanship, but one could define it more generally as dysfunctional politics. Fortunately, some citizens are at work organizing public deliberation and public-spirited advocacy during this campaign season.

Public Agenda itself is an example. The organization "advocates for a greater reliance on public dialogue to come to agreement on difficult issues." As Wooden writes, "Until leaders invest trust in the American people, create more opportunities for average citizens to explore issues from multiple points of view and help them confront the facts of our nation's greatest challenges through dialogue, our government will remain shackled by political maneuvering and gamesmanship." Check out the Public Agenda "Primer on Public Engagement."

Mobilize.org just pulled off its Party for the Presidency, a gathering of 150 young people from around the United States who developed the "Democracy 2.0 agenda" to guide their advocacy over the next year. See this coverage in the Huffington Post.

The Study Circles Resource Center, a key organization in the movement for deliberative citizenship, is about to relaunch itself as "Everyday Democracy." As one of many activities connected to the relaunch, the Center is starting an Everyday Democracy Book Club, run by Frances Moore Lappé.

And then there's the November Fifth Coalition, which is gearing up for a significant statement about how you can be involved.

Posted by peterlevine at 3:18 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

January 11, 2008

the joy of flying

(Gate 44, Washington National Airport): In December and January, I've taken 20 separate flight segments for family reasons and/or business. Two flights have been canceled outright and at least another eight have been seriously delayed. I guess nothing could be more boring than complaints about "the airlines." Still, I wonder:

1. Does anyone review an airline's decision to cancel, rather than delay, a flight? I presume that a delay costs the airline more money, because it has to be pay overtime and perhaps divert an airplane. A cancellation, however, costs the passengers much more--not only time, but also cash for wasted airport parking, ground transportation, food, etc. Canceling a flight that could instead be delayed--thereby shifting costs to the customer--should be penalized. Right now, we can't even get reliable information about why flights are canceled.

2. What's wrong with the market as a whole? Why doesn't a competitive market produce more reliable service, at least by some of the major carriers? This is not a rhetorical question--I believe that markets sometimes work and sometimes don't, and we should be able to diagnose the reason for failure in this case.

On a couple of occasions, I have fantasized about massive civil disobedience by passengers. For example, one morning, I pictured the enormous line for check-in at Dulles sitting down and refusing to budge until the airline started to issue apologies and vouchers. But the difference between a sit-in and ordinary service would have been difficult to detect.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:01 PM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

January 10, 2008

young voters in the presidential horse race (II)

Contrary to what I wrote yesterday, today's newspapers provide a bumper crop of positive stories about young voters in New Hampshire. David Nitkin in the Baltimore Sun captured the message I would most like to convey:

Voters under age 30, taking part in their first or second presidential election, belong to a deeply involved generation that volunteers at higher rates than their elders, said Peter Levine, director of the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement, at the University of Maryland, College Park.

But as they head to the polls, it is not clear whether younger voters are forging lifetime habits or are satisfied with their options.

"The big question has been, would they see voting as a helpful way to do anything about these issues?" said Levine, who surveyed 400 college students last year. "I think that they are ready to get the pitch, but they are not yet sold on the idea that the political system is the way to solve their problems."

Posted by peterlevine at 8:32 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

January 9, 2008

young voters in the presidential horse race

We have tracked young voters since 2001. In fact, CIRCLE is the only organization that provides estimates of youth turnout immediately after elections. The exit polls reveal what percentage of voters were young, but we calculate what percentage of young people voted.

We do not do this because we think that youth voting is intrinsically valuable or profoundly interesting, but because we believe that it is good for democracy--and for young people--if we can connect them to political and social institutions while they are young. Drawing attention to them as voters may encourage the press and politicians to pay attention to them, to listen to their views, and to address their issues. In turn, that attention may stimulate youth engagement with public institutions.

Thus it was very exciting when all the nation's major newspapers suddenly had prominent--often lead--articles on youth voting right after the Iowa caususes. Indeed, the statistics were startling: 65,000 young Iowans had caucused, at least three times as many as in any recent year. But in 2004, we also saw a very substantial increase in youth turnout in the general election (up 12 points compared to 2000). Yet youth turnout was widely described as disappointing that year. Yesterday in New Hampshire, the youth turnout increase was amazing, with 84,000 under-30s going to the polls. Yet I haven't yet seen too much discussion of that increase in the media.

The reason is clear. In Iowa, young people turned out strong and backed the winner. In 2004, they turned out strong but voted for Kerry, who lost. In New Hampshire yesterday, they practically doubled their turnout but voted for Obama, who lost. (Actually, the under-25s chose Obama but the 25-29s went for Clinton). Most reporters are interested in who wins. They therefore presume the following argument: Youth voted for X; X lost; ergo, youth turnout was disappointing.

At one level, I understand this. Who wins the presidency is a momentous question. But it is not the only question to ask about an election. The enormous expansion of the electorate in Iowa and New Hampshire has been a beautiful thing to watch, quite apart from who won. Besides, the horse-race frame can actually cause factual errors, as when the AP reported in 2004 that youth turnout had declined. At this point, I'm just a little concerned that youth will again be described as fickle or irrelevant, because the candidate who "needs" their vote (see Ben Adler in the Politico) happened to place second in New Hampshire.

PS I just stumbled on Ezra Klein's very thoughtful reflections on covering the horse race and what that can do to one's sense of reality.

Posted by peterlevine at 1:25 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

January 7, 2008

civic participation/economic participation

(Near Portsmouth, NH) I have a mini-essay over at the Hope Street Group blog. The Hope Street Group promotes broader and fairer participation in the market economy. I share many of its underlying principles and objectives. There is, however, a potential tension between democratic or civic engagement and the Hope Street Group's strategy. That tension involves the role of managerial expertise. Many HSG members are entrepreneurs and business executives who believe that poor management of the public sector frustrates economic opportunity. For example, some of our public school systems are adequately funded but have been managed very wastefully; and the victims are our poorest children. Importing managerial reforms from the private sector could help. Sometimes, it is very "civically engaged" Americans who stand in the way of these reforms: union leaders; school board members and their most active constituents; single-issue pressure groups; and communities that organize (for example) to preserve their own neighborhood's schools even when enrollments have shrunk.

In my mini-essay, I alert the business folks who make up Hope Street Group that not only the market sector is innovative; there's also innovation in civil society. Engaging citizens no longer means public meetings or local elections that are dominated by interest groups. We now have a much better repertoire of techniques and styles of engagement. And we need high-quality citizen participation to improve our institutions.

Posted by peterlevine at 6:16 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

to New Hampshire

I'm traveling from Syracuse, NY to Portsmouth, NH today, by various conveyances. I'm not going to the Granite State to announce my late entrance into the presidential campaign, nor to campaign for anyone else--nor to count young voters for CIRCLE. I'm just going to attend a long-scheduled meeting. However, I wouldn't be surprised if I bump into some political or media celebs on my way there or back to DC on Tuesday evening.

I've already had one brush with fame. When I was in an airport recently, I heard the following announcement: "Will Boston passenger John McCain please board immediately at gate A16. Last call for Boston passenger John McCain." I thought: there are lots of people called John McCain. But sure enough, along came the Arizona senator, hustling, grinning, and looking a little sheepish, all by himself and carrying nothing but his briefcase.

Posted by peterlevine at 5:07 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

January 4, 2008

youth turnout up very sharply in Iowa; young voters pick Obama and Huckabee

The sober analysis by CIRCLE is here. Youth turnout rose from 3 percent of eligible young participants in 2000 to four percent in 2004, and then to eleven percent last night. [Update: we're now saying, based on the last counts, that youth turnout rose to 13 percent: more than a three-fold increase.] The more dramatic version is what Mark Ambinder writes on The Atlantic.com: "REVOLUTION FOR CHANGE BEGINS? ON STRENGTH OF NEW CAUCUS GOERS, YOUNG VOTERS AND INDEPENDENTS.....OBAMA WINS DEMOCRATIC CAUCUSES........"

This year should be interesting for those of us in the youth civic engagement business.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:01 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

January 3, 2008

immigration and conservatism

On what grounds can a principled conservative oppose immigration?

One strain of modern conservatism is explicitly Christian and fundamentalist, in the specific sense that it uses the Bible as its "foundation." The New Testament seems a poor foundation for restrictions on immigration. The apostles are given the gift of tongues so that they may emigrate and convert everyone, everywhere. They show no respect for borders. "Then Peter opened his mouth, and said, Of a truth I perceive that God is no respecter of persons: But in every nation he that feareth him, and worketh righteousness, is accepted with him" (Acts 10:34-35).

Another strain is libertarian. Libertarians criticize the state for its use of force to restrain individual choice. They do not regard any state as intrinsically legitimate, but only as a tool for preserving liberty. Nothing could be more forceful than stationing agents with guns on a border to prevent individuals from moving freely across it. Immigration restrictions should be anathema to libertarians.

A third strain is free-market utilitarianism. The idea is that unrestricted markets are best for the most people--they are maximally efficient. That assumption should apply to labor markets as well as capital markets, and should therefore support free flow of people across borders. Possibly, it's good for the median US citizen to restrict the in-flow of poor people. But if we take utilitarianism seriously, it requires the most good for the most human beings--anywhere. If we are free-market utilitarians, we should favor free immigration.

A fourth strain is Burkean--skeptical about any radical changes, especially if they are engineered by law or regulation. On Burkean grounds, opening the US to massive immigration may have been a mistake in the 1960s, but reversing that policy would be equally foolish today.

A fifth strain is communitarian/traditionalist. The most attractive version of that philosophy says: Our community may not be better than anyone else's, but it gives our lives meaning and shapes our identities. We have the right to preserve its traditional outlines and to guide its growth. One might add that the traditional culture of some parts of America is English-speaking, Protestant, and of European origin (or of European and African origins). But that's no argument against immigration to New York City or LA, where the local traditions revolve around diversity and migration. Nor is it obvious that the real driver of cultural change in rural America is migration across national borders. Old ways would hardly be preserved if the newcomers were sent away.

Some conservatives have already decided that a few specific issues, such as abortion, have transcendent significance. It's not clear why they should also be opposed to immigration. In fact, new immigrants are less likely to favor abortion rights than native-born Americans are. Immigration may be a path to conservative social policy.

Finally, there's the idea of "rule of law." Actually, that's a complex idea with several components, but one element surely is the principle that a clear, written law must be obeyed and enforced. As some of the anti-immigrant activists ask, "What is it about 'illegal' that you don't understand?" I too am concerned whenever formal laws are massively disobeyed. This probably causes some loss of legitimate order and security; it also gives agents of the state too much discretion about when to enforce. But I'm not sure that rule of law is a specifically conservative principle. It is in tension with all the elements of modern conservatism listed above--and with many principles of modern progressive thought. I'd prefer to see it as a separate idea that has considerable merit when balanced against other values. (Of course, one way to respect the rule of law is to relax immigration regulations so that they are no longer widely disregarded by migrants and by American industry.)

I conclude that principled conservatives should not adopt an anti-immigrant posture. It's therefore disappointing the Republican presidential candidates should be united only by their opposition to immigration.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:50 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

January 2, 2008

"both sides now"

My sister, Caroline Levine, has an essay in Inside Higher Education about the responsibilities of peer reviewers to the authors they evaluate. She begins:

When I was a struggling junior faculty member, every publication mattered so much that rejection letters felt like physical blows. And it wasn't only the brute fact of the rejections that caused pain: Readers' reports on my manuscripts were often written in a tone of sharp annoyance. Touchy and ill-tempered, they seemed to see only the flaws. It was as if I'd somehow insulted these readers, breaking rules that I didn’t know existed. There’s no question that I’ve had much to learn about framing, pursuing, and clinching an argument. But I've certainly never had any intention of irritating my readers.

Caroline doesn't argue that reviewers should be lenient or nice to would-be authors, but she makes the case for an ethic of respect.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:03 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack