« January 2007 | Main | March 2007 »

February 28, 2007

manipulation versus eloquence

Here are two conflicting ideas that both have some appeal to me:

1) Our political system is too manipulative. The techniques of persuasion have become too effective. Instead of just sending out a mass mailing, we design several messages and test them each with a random sample of the target audience to measure its impact. Instead of sending organizers out into a neighborhood to talk to people, we give them pre-tested scripts to recite. Persuasive political advertisements are slick, scary, and produced for particular niche audiences. As a result, there is not enough listening going on, not enough two-way conversation. Real needs and good ideas cannot bubble up from below. Communication is also too strategic--not designed to explore and address problems, but to get people to do what the organizers want. Finally, the techniques of effective communication are for sale, so they tend to benefit organized groups and interests with money rather than diffuse or poorly funded interests.

2) We should prize eloquence as a skill and virtue of political participation. We teach people to express themselves effectively in writing and speech because that is part of being a good citizen. Americans need a "public voice" that can persuade others who are different from themselves on matters of common concern, not just a "private voice" that works among friends and family. As Francis Bacon said, "it is eloquence that prevaileth in an active life." Modern techniques (such as randomly testing messages) are natural refinements of traditional methods for assessing the impact of speech on audiences. They are not especially threatening, nor are they always effective; sometimes, people prefer spontaneity. When speech is free, some will be better at it than others. If their persuasiveness can be bought, that is nothing new. Protagoras sold his services as an orator in ancient Athens.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:12 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

February 27, 2007

educational accountability: cost or benefit?

In Nebraska, since 2000, every school district has been required to devise its own educational standards and tests in all core disciplines other than writing (for which there is a statewide exam). Even though many Nebraska districts enroll fewer than a thousand students, the teachers, administrators, and parents in each community must choose appropriate educational objectives for each grade and subject, design valid multiple-choice exams or other tests, and analyze the resulting data. (My source, an article in EdWeek, is behind that magazine's firewall.)

Meanwhile, in Washington DC, where my wife teaches and my daughter studies in the public schools, the district has borrowed all of its standards verbatim from Massachusetts. We also buy our high-stakes tests and some of our textbooks from big companies that construct them to match the Massachusetts standards.

You might think that all the work that goes into writing standards and tests and analyzing the data is a cost. It's the price we have to pay for keeping schools and students on task. If that price can be minimized by borrowing materials from another jurisdiction, that's a smart move. After all, kids should learn the same basic skills and facts everywhere. And designing good materials and tests is a high-skill job that most people cannot perform as well as the experts.

But there is another way to think about such matters. We might see the creation of standards and tests as an opportunity to make judgments about what is most important. By deciding what to teach, we reproduce, transmit, and adjust our culture. Each community's culture is somewhat different. For example, Washington is entirely urban, it has great historical resources, and it is the only majority-Black jurisdiction permitted to set education standards (the rest are states). Although the Massachusetts standards that we have borrowed in DC are well regarded, we may have made a mistake when we decided not to govern ourselves by writing our own. After all, Elkhorn, NE (pop. 7,635) seems to have done a pretty good job with theirs.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:29 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 25, 2007

the Clinton/Obama spat

(A belated comment. ...) I don't think last week's exchange of accusations was particularly significant; by itself, it won't affect either campaign. But it did reveal weaknesses that both candidates should address.

For Senator Clinton (whom I refuse to call "Hillary"), it should be a reminder that three of her strengths have concomitant disadvantages. She represents an administration that looks pretty good in retrospect. She has been popular in Hollywood. And she has lots of powerful and wealthy supporters. However, she needs a forward-looking vision, some distance from Hollywood, and a way of mollifying voters who dislike money in politics. Last week, she seemed to be angry because a movie mogul who used to give her lots of money had criticized the Clinton Administration. That was dangerous territory for her.

For Senator Obama, the spat underlined the importance of going far beyond "civility." When the Senator calls for a new type of politics, the press hears a promise to be more polite to other politicians. That is a promise that Obama will not be able to keep in the heat of a competitive national campaign. Thus he will inevitably be branded as a hypocrite. Besides, although civility may have some value, it is far from adequate. We won't see civic renewal in America just because our candidates reduce their mean-spirited personal attacks.

A sympathetic reading of Obama's speeches and writings suggests that he wants to change the role of American citizens in politics (not just the behavior of candidates on the campaign trail). He wants to unleash Americans to develop their own responses to fundamental problems. The press ignores those parts of his speeches because they assume that he is just spouting democratic bromides--it's all throat-clearing. All they hear is a promise to be more polite to his rival candidates. In order to show that he is serious about civic renewal, Obama is going to have to be concrete about it. That means making arguments for national service, broader economic roles for municipalities, land-trusts, net-neutrality, civic education, public participation in the response to Katrina and future disasters, and possibly charter schools.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:05 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

February 23, 2007

managing risk

In an age of weak family structures and communities--and unstable employment--individuals and nuclear families are on their own; they need to be able to manage risk so that they can bounce back from adversity. To help people to hedge risk is different from guaranteeing their welfare or reducing social inequality. It probably isn't adequate, but it is important in the current era of high volatility.

What are the big economic risks for Americans, especially for the working class? Being laid off or seeing one's salary drop dramatically, perhaps because of a reduction in paid hours. Sickness or injury, including injury caused by crime. Divorce and widowhood. Kids who are sick or in trouble. Business failure, including the failure of very small enterprises such as trading pages on e-Bay. Loss of property (such as homes and vehicles) due to robbery, fire, or accidents. Steep declines in the value of one's home or land, such as we see in Rust Belt cities and the Farm Belt.

There are financial instruments designed for some of these risks--for example, home insurance. But sometimes such instruments are too expensive for people whose property is particularly modest. Other risks do not seem to be covered at all by available insurance (divorce, for instance; or the delinquency of one's child). The government covers some people's medical care, but many are not eligible for Medicare or Medicaid and cannot afford private packages. The state is supposed to prevent crime in the first place and can sometimes order restitution. But crime can devastate its victims.

It's interesting to envision a comprehensive set of mechanisms for managing these risks. Some mechanisms could be provided by the state or state-subsidized. Others might be developed by private organizations.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:36 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 21, 2007

building alternative intellectual establishments

Think back to the year 1970. ....

Almost all university professors are men. They seem to be interested only in male historical figures and male issues. They select their own advanced students and colleagues and decide which manuscripts are published. They defend their profession as rigorous, objective, and politically neutral. Feminists respond by criticizing those claims; some also try to create a parallel set of academic institutions (women's studies departments, feminist journals) that can confer degrees and tenure and publish. Certain academic disciplines, including law, history, and political science, are seen as predominantly liberal. They seem to support a liberal political establishment that has considerable power. For example, law professors are gatekeepers to the legal profession, which produces all judges. Professors in these fields choose their own successors and claim to be guardians of professionalism, expertise, independence, and ethics. Conservatives--disputing these claims--decide to build a parallel set of research institutions, including the right-wing think tanks and organizations like the Federalist Society (founded 1982). The National Endowment for the Arts gives competitive grants to individual artists. NEA peer-review committees are composed of artists, critics, and curators. They are said to be insulated from politics and capable of choosing only the best works. The artists they support tend to come from the "Art World" to which they also belong: a constellation of galleries, art schools, small theaters, and magazines, many based in New York City. Most of the funded work is avant-garde. It is usually politically-correct, aiming to "shake the bourgeoisie." Critics complain about some particularly controversial artists, and ultimately the individual grants program is canceled. Almost all professional biologists are Darwinians. They assert the legitimacy of science; but their religious critics believe that they depend on false metaphysical assumptions. Biologists use peer-review to select their students, to hire colleagues, to disperse research funds, and to choose articles for publication. Religious critics cannot get through this system, so they build a parallel one composed of the Institute for Creation Research, Students for Origins Research, and the like. The most influential news organs in the country (some national newspapers and the nightly television news programs) claim neutrality, objectivity, accuracy, and comprehensiveness: in a phrase, "all the news that's fit to print." Critics from both the left and right detect all sorts of bias. They try (not for the first time in history) to construct alternative forms of media, including NPR (founded in 1970) and right-wing talk radio.

If you are influenced by Nietzsche's Genealogy of Morals and Foucault, you may see all knowledge as constructed by institutions to serve their own wills to power. Then you must view all of the efforts mentioned above with equanimity--or perhaps with satisfaction, since they have unmasked pretentious claims to Truth. If you believe in separate spheres of human excellence, then you may lament the way that various disciplines and fields have been enlisted for political organizing. You may concede that all thought has a political dimension, but you may be sorry that scholarly and artistic institutions have been used as strategic resources in battles between the organized left and right. (I owe this idea to Steven Teles.)

I guess my own response is ad hoc and mixed. For example, I think that conservative ideas about law, history, and political science are interesting and challenging and should be represented in academia. I'm sorry that some legal conservatives have found their way to the Supreme Court, but the solution is to win the public debate about the meaning of the Constitution--not to wish that conservatives would go away. The Federalist Society provides liberals with a valuable intellectual challenge.

I suspect that the NEA's peer-review committees of the 1970s and 1980s often identified the best artists: meaning those who were most innovative, sophisticated, and likely to figure in the history of art as it is written a century from now. (Although who can tell for sure?) But I'm not convinced that taxpayers' money should be devoted to the "best" artists. Other criteria, such as geographical dispersion, various sorts of diversity, and public involvement, should perhaps also count. If it's fair to say that the New York Art World dispersed public money to itself, that sounds like a special-interest takeover of a public agency.

Finally, "creation science" and "intelligent design theory" strike me as both scientific and theological embarrassments, destined to disappear but not before they have done some damage. Nevertheless, the anti-Darwinian organizations reflect freedom of association and freedom of speech and must certainly be tolerated.

(These ad hoc judgments are probably not consistent or coherent at a theoretical level.)

Posted by peterlevine at 9:06 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

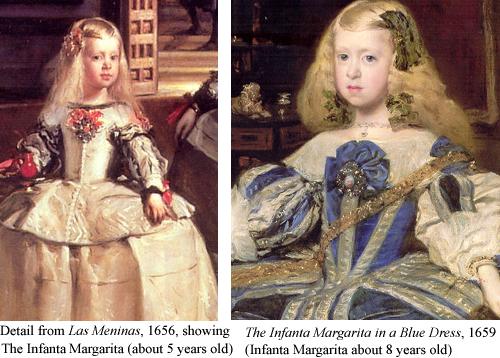

was Velazquez left-handed?

My post from 2005 on Las Meninas, Velazquez' masterpiece, has drawn some very interesting and original comments. The latest contribution comes from Barbara Robinson of London Ireland who, like Colin Dixon, believes that the whole painting is a mirror image. Ms. Robinson adds some evidence. These two paintings are both by Velazquez and they show the same girl, the Infanta Margarita, three years apart. The image on the right is a detail from Las Meninas; the one on the left is part of a freestanding portrait.

Barbara Robinson (who sent me these images) emphasizes the parting of the hair and "the decorative hair slide," which are reversed in these two pictures. Her son adds that if Las Meninas is an image in a mirror, then Velazquez is shown holding his paintbrush in his left hand, which makes him what we Americans call a "southpaw." (Note that there were very large mirrors in Valazquez' day.)

Posted by peterlevine at 10:57 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

February 20, 2007

protest, now and then

A reporter recently asked me how much protest and other activism is going on among today's youth, compared to their predecessors during the Vietnam era.

In 1973, the General Social Survey asked about five specific forms of protest (prowar, antiwar, civil rights, labor-related strikes, and school events). About 28 percent of the young people in that survey (ages 18-25) said they had participated in one or more of those types of protest.

In 2006, we found that 11.5% of 15-25-year-olds had attended any protest, march, or demonstration (regardless of topic).

Given the different questions, the comparison is not perfect. Still, these results suggest some decline in the rate of physical protest by young people. That trend has to be set against a lot of volunteering and online activism, which Jennifer Earl described recently in the Washington Post. (Her article was entitled, "Where Have All the Protests Gone? Online.") In our 2006 survey, 15% of the young respondents said they had signed email petitions--less than the 21% rate among older Americans, but still a large number. And if we added other formats, such as social networking sites, we would see even more online activism.

Posted by peterlevine at 2:55 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 19, 2007

the "fit" between cultures and the labor market

Poverty and privilege reproduce themselves. If you are an American boy born in the poorest tenth of the population, you have only a 1.3 percent chance of reaching the top ten percent during your lifetime, and just a 3.7 percent chance of becoming at all wealthy (in the top fifth). If you are a male born in the bottom tenth, the odds are more than even that you will never make it out of the bottom fifth.

It's not only that people from wealthy background have more capital and better contacts and receive more economic investments (for example, more money is spent on their schools). In addition to those factors, their relatives and peers make sure that they are ready to flourish in the white-collar work world. There is, in other words, an excellent "fit" between their background culture and the labor market. That fit is much worse for kids from working-class homes.

At least three reasonable objections can be made when people mention this problem: (A) It seems to let the government off the hook for providing poor schools and public services. (B) It seems to criticize people for not preparing their children well for the workforce. And (C) it can be viewed as a coded way of making a point--probably a hostile point--about racial minorities in America.

Therefore, let me say: (A) Inequitable public policies make matters considerably worse than they would be if our problems were simply cultural. (B) When there is a poor fit between a particular culture's norms and the demands of the white-collar workplace, I do not automatically assume that the norms ought to change. Often I admire groups that resist the dominant economy. (C) I don't think race is the issue in this case. Annette Lareau set out to explore differences in parenting by race and class, expecting to find that both factors would matter (as they often do). But what she actually observed were striking similarities in the parenting of African American and White children of similar economic classes. Her work is a vivid depiction of the cultural norms of our two biggest classes and how they reproduce themselves. The differences among smaller cultural groups (e.g., scientists, evangelicals, Chicagoans) may also matter, but they don't map onto racial categories.

Some specificity is useful here. The question is not which cultures fit well with "capitalism," because capitalism is an old, varied, and flexible phenomenon. The question is which cultures prepare young people best for a particular life that is characterized by meetings and conference calls, schedules and budgets, offices, suits, emails that read like memos, businesses lunches, handshakes, thank-you notes and holiday cards, business travel, interviews, proposals and bids, job descriptions, mission statements, PowerPoints, and websites. This world envelops people who are not straightforwardly involved in "capitalism." For example, it is my world, even though I am a philosopher at a public university. But it leaves out the working class and the unemployed, stay-at-home parents and retirees--and any true bohemians we have left.

The "field" of white-collar work is saturated with norms and expectations. Children whose parents belong to it are raised from an early age to succeed in it. They are taught to speak as if at a business meeting, to analyze their own interests, and to negotiate on their own behalf. Modern middle-class childhood has some unattractive features. These kids are often competitive with siblings, unable to handle unstructured time, quick to quit situations that seem unprofitable or uninteresting, and over-conscious of their own entitlements. But those attitudes pay off in the labor market.

Schools try to compensate for the differences in home cultures. In fact, they may overlook the talents of working-class kids--such as their ability to fill free time with self-organized activities--because they are so eager to prepare everyone for the white-collar work world. But schools cannot fully compensate for the cultural advantages of the middle class. They cannot provide enough one-on-one interactions between adults and students to train kids for situations that will involve bilateral communication, negotiation, and self-presentation. Besides, on average, teachers are themselves a little marginal to the "field" of white-collar work. Of all professionals, teachers are some of the least experienced in negotiating contracts, making business trips, or participating in conference calls. Their daily interactions are mostly with groups of children, not with peers behind desks or on the phone.

The most radical response to this problem would not be to reform educational institutions so that they better prepare all children for the white-collar workforce, nor to compensate for inequalities in the labor market by providing better social insurance. The most radical response would be to enlarge the supply of stable and rewarding jobs that embody different values and skills from those of the white-collar world.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:22 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

February 16, 2007

putting philosophy back in developmental pyschology

I'm involved right now in several collaborative projects with developmental psychologists. I constantly learn from these empirical colleagues. However, it often strikes me that civic development is rife with "normative" purposes and controversies. We educate people for citizenship because of our conceptions of ethics, character, liberty, and social justice. If I have anything to contribute, it's by drawing explicit attention to those issues.

Below the fold is the draft of a chapter that I'm writing to alert psychologists to some normative questions that ought to concern them if they are interested in "citizenship." My strategy is to introduce the various major schools of modern moral/political philosophy (utilitarianism, Kantianism, and the rest) and ask what each school would make of current forms of civic education. I'm not fully satisfied with this approach. It leads me to offer simplistic accounts of the main schools of modern philosophy. Besides, many real philosophers are eclectic, seeing the intuitive merits of more than one school. At the moment, however, I cannot think of a better way to begin. ...

Educating young people for citizenship is an intrinsically "normative" task. In other words, it is a matter of choosing and transmitting values to citizens so that they will build and sustain societies that embody particular forms of justice and virtue. Adults who teach history, civics, or social studies, who guide adolescents in community service projects, or who recruit youth as activists generally do so for normative reasons—because of values that they hold and wish to transmit. Likewise, most scholars who evaluate and study such work do so because of their own demanding moral principles. Yet it is relatively rare to disclose and defend the precise normative reasons for particular forms of civic education in schools or other institutions.

This lack of explicit attention to normative reasons is unfortunate. Reasonable people have defined "good citizens" in various ways: for example, as dutiful members of communities, as independent critics of public institutions, as bearers of rights, and as proponents of social justice. Deciding which of these values to transmit is a public task in which everyone has a stake. Adults who lead and/or study civic education may have considerable influence over youth, who are not fully capable of making their own choices. As a matter of accountability, these adults ought to explain—both to the youth they serve and to other adults—which civic values and habits they are trying to develop, and why. In short, they must be willing to participate in a democratic discussion about their public work.

Second, explicit discussion of values can reveal the tradeoffs that often arise in civic education. One category of tradeoff (as an example) involves quantity versus equality. Many voluntary programs attract adolescents who already have relatively strong commitments to civic engagement and relatively strong skills for civic and political participation. Student governments, for instance, usually draw students who are already on a leadership track. Those students tend to be successful in school and thus likely to hold privileged social positions as adults. Offering them civic opportunities may enhance their capacity to participate in politics and community affairs. That is a good result if we want to increase the total amount of civic engagement in the next generation. But it is a bad outcome if we are mainly concerned about equality of civic participation by social class.

Another type of tradeoff involves freedom versus moral authority. Even if it is desirable for young people to become tolerant, trusting, caring, and committed to the common good, there is a separate question about whether any particular group of adults (e.g., parents, teachers, policymakers, or taxpayers) has a right to inculcate these values.

Third, explicit normative argumentation can provide persuasive reasons to invest in civic development—reasons that would otherwise be overlooked. Today, the default justification for any educational investment is its impact on individual students’ long-term “human capital”: their value in the labor market, as revealed by their grades and degrees. There is evidence that some civic opportunities increase human capital. For example, mandatory service-learning in high school seems to improve students’ grades and increase their likelihood of completing college. However, many adults who organize such opportunities have defensible motives other than enhancing human capital. By elucidating these alternative reasons, we may be able to increase public support for civic development. We may also reduce our dependence on fragile empirical rationales. For instance, even if service-learning enhances students’ grades, it may turn out that other interventions do so more efficiently. Should we therefore give up on service-learning? That would be an appropriate conclusion if the only purpose of service-learning were to increase human capital. But there are other plausible reasons for it.

Contemporary moral and political philosophy provide rich and diverse resources for thinking about youth civic development. After several decades of ground-breaking empirical work on civic development (including a paradigm shift to "positive youth development"), it would now be useful to renew the dialogue between psychology and philosophy. One starting point is to ask how each of the main current schools of moral philosophy would assess major forms of civic education. Actual philosophers are often eclectic, drawing from more than one school or tradition. Nevertheless, these main schools provide useful heuristics.

One major stream of modern moral reasoning is consequentialist. It assesses any action or institution by measuring its net outcomes or consequences. The leading subset of consequentialism is utilitarianism, which presumes that the consequences that matter are measures of human welfare. Welfare, in turn, can be defined in terms of subjective satisfaction or happiness; objective indicators, such as life-expectancy; or the ability to satisfy preferences. Utilitarianism has had an enormous influence on welfare economics and, more generally, the social sciences.

A utilitarian might favor civic opportunities because they have been found to enhance students’ welfare. For instance, an evaluation of the Quantum Opportunities Program studied randomly selected students and a control group. For about $2,500/year over four years, QOP was able to cut the dropout rate to 23 percent, compared to 50 percent for the control group. QOP’s approach included academic programs that were individually paced for each student; mandatory community service; enrichment programs; and pay for each hour of participation. For a utilitarian, the cost of this program would be a disadvantage (because having to pay taxes presumably reduces the welfare of the taxpayers); but the social benefits might outweigh the costs. People who complete high school generally have more welfare than those who do not. They also contribute more to the economy, thereby enhancing other people's welfare.

One standard argument against utilitarianism is that it overlooks fairness among individuals by focusing on aggregate welfare. There are situations in which making disadvantaged people even worse off can increase aggregate social welfare; in such cases, simple utilitarianism is blind to fairness. However, utilitarians can provide indirect arguments for focusing resources on the most disadvantaged young people. One argument is that the marginal benefits are likely to be greatest when we offer opportunities to adolescents who would otherwise be “at risk” of failure in school. For instance, the QOP program obtained efficient outcomes because it was directed at disadvantaged middle-school students who were otherwise likely to become pregnant.

The other utilitarian argument for equity is political. Jeremy Bentham, the first utilitarian, asserted that representative democracy was the form of government that would best promote aggregate welfare. Democratic governments were most likely to address genuine public needs and allocate resources efficiently. Our actual democracy, however, is marked by highly unequal participation and does not respond equally to everyone’s needs. In order to achieve more equitable representation, we need to help young people develop the skills, habits, knowledge, and motivations that will increase their participation.

Utilitarianism does not provide direct reasons to protect individual freedom and choice. It values freedom only insofar as empirical evidence shows that people who are free in particular respects are therefore happier. Utilitarians should support mandatory civic education programs that enhance social welfare even if youth do not wish to enroll. Indeed, most Americans have utilitarian intuitions with respect to adolescents: we are willing to override young people’s freedom to promote their welfare.

Unlike utilitarianism, Kantianism puts autonomy at the center. Immanuel Kant is perhaps best known as the proponent of the Categorical Imperative, which says that we must be able to generalize the "maxims" of our actions so that they would apply to everyone in similar circumstances. This principle proves vague in application, and many contemporary Kantians believe that the useful heart of his philosophy lies elsewhere. Kant argued that we had two fundamental duties: to develop our own rational autonomy, and to help others develop and pursue reasonable goals of their own choice. The measure of an action was not its consequences, but the quality of the free human will that lay behind it. To be autonomous, goals had to be freely chosen, but they also had to be rational (i.e., examined, coherent, and capable of public justification).

A Kantian would not be concerned about the impact of civic programs on objective measures of welfare, such as graduation rates. However, a Kantian might be very impressed by programs or opportunities that seemed to enhance the autonomy of their participants. Programs would seem especially promising to Kantians if they encouraged young people to reflect upon moral issues and choices, form and defend their own opinions, and act accordingly. (Some of these behaviors can be measured empirically.) Kantians might also value outcomes such as success in school, but only as indirect evidence that students were developing autonomy.

Both Kantians and utilitarians have reasons to favor programs such as QOP (assuming that the evaluation cited above is accurate). However, their reasons are quite different, and this difference matters when we confront questions such as whether to mandate service-learning, whether youth should always lead their own service projects, or whether to count economic welfare as a positive outcome of service. These issues are complex, and Kantians need not always take different sides from utilitarians. For instance, although utilitarians are not directly concerned about freedom, they might be dissuaded from imposing service requirements if such obligations usually breed resentment. Kantians care a great deal about freedom, but they might support a service mandate if service reliably expands young people’s sense of options and possibilities and therefore enhances their autonomy. Nevertheless, the two kinds of moral analysts will seek different evidence and may reach different conclusions in concrete cases. They will also justify the very same program in different ways; and justifications matter in the public debate.

A third relevant stream of modern philosophy is civic republicanism. Its core idea is that civic participation (deliberating, collaborating, volunteering, advocating, and voting) is not a cost. It is not work that we must unfortunately do in order to sustain a just society. Rather, it is a good, an intrinsically dignified and rewarding form of human behavior. Some civic republicans rank various human pursuits and place political activism high on their lists. Aristotle, for example, considered politics the second-highest way of life after philosophy itself. Others are pluralists. They do not believe that there is one universal and objective ranking of human goods, but they consider civic participation to be a good rather than a cost.

Civic republicans may view civic opportunities for young people as intrinsically valuable, regardless of their outcomes. For example, a one-time service project is unlikely to boost any long-term outcomes; thus it has weak appeal for utilitarians. But civic republicans could argue that schools and colleges are communities. Good communities offer opportunities for collaboration and service. Therefore, even one-time service projects are valuable.

Civic republicans could argue, further, that young people should be exposed to the satisfactions of participation so that they may choose to be engaged when they are adults. We are barraged by advertising for other goods, such as consumer products. Civic participation is not widely promoted. Civic republicans might see effective forms of civic education as advertisements for participation.

The philosophical schools mentioned so far consistently apply a few abstract principles to all relevant cases. That methodology has itself been criticized, most notably by proponents of an "ethic of care." Drawing on Hume, Hegel, and other classic sources, they argue that our duties are not abstract and general, but derive from our particular connections to fellow members of our own communities and families, with whom we have common histories. Certain kinds of civic opportunities--especially voluntary service--seem to embody an "ethic of care." But critics charge that care is inadequate without a conception of social justice.

As mentioned earlier, many actual philosophers draw on more than one tradition in developing their views. An important and relevant example is the "capabilities approach" as defended by Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum. Sen and Nussbaum share the Kantian intuition that autonomy is an essential human value. They criticize objective measures of social welfare, because free human beings may reasonably choose not to pursue these outcomes. For example, some communities are committed to religion rather than affluence. The fact that monks do not eat well does not mean that they lack welfare. Likewise, an individual may choose hardships in order to be closer to nature.

On the other hand, Sen and Nussbaum reject the idea that autonomy is simply a matter of free choice. First of all, some actual choices harm the true interests of the individual: using addictive narcotics would be an example. Other choices reflect a narrow sense of what is possible, constrained by cultural biases. Moreover, people need goods before they can be truly autonomous: for instance, education, legal rights, and a sense of self-respect.

Therefore, Sen and Nussbaum recommend "capabilities" as the criteria of social justice. In a good society, everyone has certain core capabilities, such as working, playing, raising children, participating in politics, and appreciating nature and art. These capabilities can be expressed in various ways or even forgone, depending on the free choices of individuals. For example, if I have a capability of raising children but choose not to act on it, there is no injustice.

The capabilities approach would support certain forms of youth civic engagement, for several reasons. The youth themselves would develop a capability for political participation. Some of their other capabilities might be strengthened as well; for example, service appears to boost educational success. Finally, Sen and Nussbaum believe that communities must decide democratically how to develop and promote the capabilities of their own members. Their list of human capabilities is intended to be objective and universal, but many subsidiary choices remain to be made democratically. By developing young people’s skills of social analysis and deliberation, we help to promote democratic decision-making.

Posted by peterlevine at 4:06 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 15, 2007

the small screen

I just did a taped interview with CBS News on young people's activism. I'm glad CBS is doing a segment on this topic, and the producers were well-informed. I don't know how my own interview went. It was an unnatural format--staring at a dark room with a lot of bright lights while questions came into my ear from New York. I think I would have been more animated, humorous, and responsive if I'd been able to see an embodied human being. But at least I got in some basic points about the rise in volunteering rates and the high level of online activism.

If I find out when the segment airs or get a link to the video, I'll post it here. Whether or not I make the final cut, the segment should be interesting.

Posted by peterlevine at 3:13 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 14, 2007

a true story, a propos of nothing

It is 1617. Edward Coke, until recently the Lord Chief Justice of England and before that the implacable prosecutor of Guy Fawkes, Sir Walter Ralegh, and the Earl of Essex, has been fired by King James for defending the common law and sent away in disgrace. But Coke has a new reason for hope. His daughter Frances, age 15, has an opportunity to marry Sir John Villiers, brother of the Duke of Buckingham. Buckingham is King James' "favourite"--his inseparable partner, chief adviser, and probably his platonic lover.

Unfortunately for Coke, his own wife is his most bitter enemy. She is Lady Elizabeth Hatton, a beautiful, enormously rich, young, and fashionable courtier. Coke and Lady Hatton live apart and are constantly suing one another. Lady Hatton now choses to block her daughter's proposed marriage to Sir John Villiers. In the middle of the night, she takes Frances away to a country house called Oatlands.

She tells the girl that a very high-born nobleman, Henry de Vere, the eighth Earl of Oxford, wants to marry her. This is a complete invention, but de Vere is safely in Venice on his Grand Tour and cannot be consulted. Poor Frances writes and signs an oath "gyv[ing] myselfe absolutely to Wyffe to Henry Vere Viscount Balbroke Erl of Oxenford to whom I plyghte my trothe and inviolate vows to keepe myselfe till Death us do part: and if I even brake the leaste of these I pray God Damne mee Bodye and Soule in Hell fire in the world to come: and in theis world I humbly beseech God the Erth may open and swallow mee up quicke to the Terror of all fayhte breakers that remayne Alive."

That is a pretty clear and forceful oath; Frances' marriage to Sir John Villiers now seems impossible. But Edward Coke arrives with a large band of armed men and a warrant to search Oatlands. He shouts that if he is forced to kill anyone to gain entrance, that will be justifiable homicide; but if any of his men are killed, it will be murder. With the help of a battering ram, he gains entrance to the house and removes Frances.

Lady Hatton goes immediately to Coke's nemesis, Sir Frances Bacon, who was responsible for her husband's disgrace. Bacon is sick and will not see her, but she finally bursts into his bedroom and demands a warrant to reclaim her daughter. Bacon sends her to the King's Privy Council, of which he is a member. The next morning, she addresses the Council in a "somewhat passionate and tragicall manner." She receives an order for the custody of Frances and heads to Coke's house to enforce it, accompanied by "three score men and pistolls."

Meanwhile, Bacon is trying to end Coke's career once and for all--and gain some credit for his work. He writes to Lord Buckingham, noting the many disadvantages of a match between Frances Coke and John Villiers. Coke's house is "disgraced," a "troubled house of man and wife, which in religion and christian discretion is disliked." Etc.

The Privy Council meets to consider charges against Coke for "force and riot" and other offenses. The tide is running against him; there is even a motion to discipline the member of the Council, Secretary Winwood, who had given Coke the original warrant to seize his daughter. Once everyone has expressed disdain and animus for Coke, Winwood pulls out of his pocket a letter from the King himself. James (and therefore, surely, Buckingham) strongly favor the match between Edward Coke's daughter and Sir John Villiers.

Now Bacon is in serious trouble; he has interfered with and insulted a union planned by his sovereign and his country's most powerful courtier. He receives a letter from Buckingham that must sink any remaining hopes. "In this business of my brother's that you overtrouble yourself with, I understand from London by some of my friends that you have carried yourself with much scorn and neglect toward both myself and friends; which if it prove true I blame not you but myself, who ever was your Lordship's assured friend, G. Buckingham." Not long after, a letter arrives from the King himself, whose style is far more direct and biting.

The wedding takes place at Hampton Court, although Lady Hatton is temporarily held under house arrest to prevent her from causing a scene. While Frances awaits her marriage, she writes an ingenuous and touching letter to her mother. The spelling, unfortunately, has been modernized, but one can follow the halting thoughts of the 15-year old as she sets them to paper.

She begins by trying to express loyalty. "Madam, I must now humbly desire your patience in giving me leave to declare myself to you, which is, that without your allowance and liking, all the world shall never make me entangle or tie myself." However, she is about to be "entangled" to John Villiers--completely against her mother's will. Her father is forcing her to set this unfortunate fact on paper. "But now, by my father's especial commandment, I obey him in presenting to you my humble duty in a tedious letter, which is to know your Ladyship's pleasure, not as a thing I desire." This sentence continues through several more wavering clauses, the main point of which is her hope for family harmony. "I resolve to be wholly ruled by my father and yourself"--not possible, under the circumstances--"knowing your judgements to be such that I may well rely upon, and hoping that the conscience and natural affection parents bear to children will let you do nothing but for my good." (We watch Frances' faith in her parents' judgment diminish to mere "hope," perhaps as she recalls their recent behavior.) "So I humbly take my leave, praying that all things may be to every one's contentment, Your Ladyship's most obedient and humble daughter for ever, Frances Coke."

(I take this story and all the quotes from Catherine Drinker Bowen, The Lion and the Throne: The Life and Times of Sir Edward Coke, 1552-1634. This biography won the National Book Award for nonfiction in 1958 and is a great read.)

Posted by peterlevine at 10:27 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 13, 2007

youth mapping this summer

This summer, my colleagues and I will help run a pilot course for adolescents in Prince George's County, MD. We will teach these young people to identify issues or problems that they want to address, and then "map" the networks of groups and individuals that could make a difference. They will document their work for public display, although we haven't decided what medium they should use: their art works, audio recordings, audio plus still photos, or video.

Along with colleagues at the University of Wisconsin, we have submitted a large grant proposal that would allow us to develop and pilot elaborate software for such courses. This software would allow teenagers to make diagrams of local social networks, much like the "network maps" that are popular in sociology today. However, our community partners cannot wait to find out if we get money for software-development. Therefore, we have committed to teach the pilot courses whatever happens, if necessary using old-fashioned tools like magic markers and poster board.

Two of the essential principles are: youth voice (students should be assisted in developing their own agenda and analysis, without presuppositions from us) and a particular understanding of power. "Power" will be defined not merely as official authority (like that of a mayor or a school principal) but also the capacity of ordinary residents to make a difference by working together. That is why we will help youth to map local networks of citizens.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:23 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 12, 2007

the Jonathan Tisch College of Citizenship at Tufts

I'm just back from visiting the Tisch College of Citizenship and Public Service at Tufts University, which is a very unusual and courageous experiment. At Tufts, there are several prominent experts on "active citizenship"--political scientists, psychologists, sociologists, and staff who guide students in service projects. To build on this strength, the university founded--and Jonathan M. Tisch, the chairman of Loews Hotels, endowed--a College of Citizenship and Public Service. The College does not grant degrees, enroll students, or offer courses. Its founders felt that a standard school or college would only affect a subset of Tufts' students and faculty. It would become a specialized program, perhaps devoted to training future civil servants. Instead, the Tisch College exists to infuse active citizenship throughout the undergraduate education, graduate and professional schools, extracurricular activities, research, and community relations of Tufts.

The Tisch College is still in its early years, but it has already produced a stream of publications, programs, and events.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:32 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 9, 2007

Facebook and politics

(In Cambridge, MA) Students don't give a lot of money to political candidates; they don't have enough to give. In 2004, according to the American National Election Study, just 1.3% of young people (ages 18-25) said they had given money to any political candidate. In contrast, 10.1% of people over the age of 25 had made financial contributions.

However, the independent group Students for Obama (which started on FaceBook and now has 50,000 members) has figured out a way to have an impact. They write, "We understand that money is not exactly something we all have a lot of to spare; that's why we put together a list of some of the things you can skip or pass on once--and donate the amount you saved. Next time you are going to spend money on one of these items, think of instead helping break the stereotype that students do not donate and do not care about the political process." They suggest, for example, that you give up your next Starbucks Caramel Macchiato and give the $3.21 to Obama. It will be interesting to see whether this practice spreads as the '08 campaign unfolds.

[Update: see Jose Antonio Vargas' good article in the Washington Post, which cites our work. He says that the Obama Facebook site now has 279,000 members and rising.]

Posted by peterlevine at 11:40 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 8, 2007

citizen media update

(en route to Boston) My colleague Jan Shaffer has issued a report entitled "Citizen Media: Fad or the Future of News? The Rise and Prospects of Hyperlocal Journalism." Her conclusions are based on detailed interviews with the people involved in 31 citizen news ventures, plus a survey of 191 other projects. "Hyper-local" news media represent alternatives to the increasingly homogeneous news business and provide opportunities (like nothing we have seen since the 19th century) for great numbers of people to produce news. These projects encompass websites, but also low-powered radio stations, email lists, and even some printed publications. They serve neighborhoods and small towns and dispersed affinity groups. They tend to combine some original information, some news selected from commercial sources, and some opinion and analysis.

I haven't had the chance to read Jan's important report all the way through, but I have skimmed it and highly recommend it.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:26 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 7, 2007

three forms of populism in the 2008 campaign

It appears that the next presidential campaign will offer several strong but contrasting flavors of populism:

Sam Brownback asserts that Americans' traditional, popular, moral values are threatened by the "violence, obscenity, and indecency in today’s media," by "activist judges," by "foreign suppliers" of oil, and by the federal government. I happen to disagree with almost all his positions, but the Senator does share the majority's view of several issues, such as prayer in schools.

John Edwards makes the case that we all belong to one economic community, one commonwealth, and inherit our national prosperity not because of what we do as individuals but because of others' sacrifices, past and present. "We are only strong because our people work hard." "We are made strong by our longshoremen and autoworkers, our computer programmers and janitors, and disrespect to any of them is disrespect to the values that allowed for America's greatness in the first place." Since we belong to one commonwealth, gross disparities in opportunities are unfair.

I used to believe that this position--while morally valid--was a political dead end. Although we had left many Americans in poverty, more than half of all voters were affluent enough that they didn't need government except for purposes that are always well funded, such as roads and suburban schools. "Redistribution" meant "welfare," and the welfare system that had developed since the 1930s was justifiably unpopular. Finally, Americans' were strongly committed to markets and mistrustful of governments.

But several factors make Edwards' version of populism more promising today. Federal welfare has been deeply cut; the remaining safety-net programs serve large majorities of Americans. The issue has shifted from income inequalities (which Americans tend to tolerate) to huge inequalities in risk. Most people must finance their own retirements while some get huge golden parachutes, exemplifying a new kind of unfairness. Meanwhile, the latest generation of super-rich people has behaved very badly: Paris Hilton is a potent symbol. Not least, John Edwards is a skillful persuader, a litigator who knows how to read a jury and marshal effective evidence and arguments.

Barack Obama so far represents a different strain of populism. He says that we American citizens should play a central role in defining and solving our common problems. We are in a "serious mood, we're in a sober mood," and we are ready to work together. "We are going to re-engage in our democracy in a way that we haven't done for some time, .... we are going to take hold of our collective lives together and reassert our values and our ideals on our politics. ... All of us have a stake in this government, all of us have responsibilities, all of us have to step up to the plate."

For Senator Brownback, the way to assert our values is to pass laws that he favors and that have majority support. For John Edwards, "the great moral imperatives of our time" are to fight poverty and get out of Iraq. For Senator Obama, asserting our values means deliberating together as a diverse population and developing ideas that may be new and unexpected.

In philosopher's terms, this is civic republicanism, and it's truly different from mainstream recent liberal politics. To make it work, Obama will have to overcome two challenges. First, he will have to develop an answer for grassroots Democratic activists who are furious at Republicans and consider the Bush administration to be our nation's central problem. Obama believes that both parties are responsible for marginalizing citizens, and what we need are broader public coalitions. The Senator will have to find a way to talk to Democratic primary voters who are not in the mood right now for non-partisanship and cooperation. Second, Obama will have to find a way to respect the voice of American citizens while also saying something concrete about issues such as health care and taxes. He needs to respect the public's voice but also perform the main duty of a candidate, which is to put ideas on the table.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:00 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 6, 2007

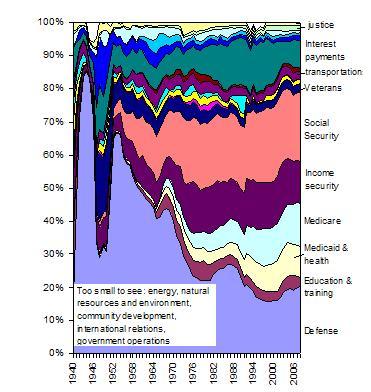

the federal budget

On the day after the president released his 2008 budget, it might be helpful to take a longer view. Below I show the percentage of the total budget (also known as "your tax dollar") that is devoted to each major category of federal spending. I've set the total for every year to 100%, but of course the actual size of the budget has grown enormously. The last year (2008) is the president's proposal, which will not be implemented as he wishes. On the other hand, his proposal will not be changed enough to make a visible difference on a graph at this scale.

The graph is helpful in making a few points that I don't think most citizens realize. First, you cannot cut spending appreciably without touching defense, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. (Interest payments are automatic.) Second, Medicare and defense are the two items that have expanded rapidly of late. Third, some categories that provoke opposition, such as foreign aid and grants to artists and scholars, are far too small even to be illustrated. Finally, despite all the storm and stress over important details, both of our major parties are basically committed to the same kind of budget.

Posted by peterlevine at 3:11 PM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

February 5, 2007

sunlight, the best disinfectant

In 2006, Senator Jon Tester (D-MT) and Rep. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY) defeated incumbents who were tied to Jack Abramoff--our latest exemplar of a corrupt lobbyist. In an effort to demonstrate their own commitment to "transparency," Tester and Gillibrand pledged to disclose their daily schedules for all to see. See Tester's schedule here and Gillibrand's here.

Lindsey Layton (who met with Tester at 2:15 pm on January 30, according to the Senator's public schedule) describes these online diaries in The Washington Post. Layton writes, "Richard A. Baker, the Senate historian, cannot find a precedent for what Tester and Gillibrand are doing." But there is precedent for the underlying principle. In 1905, as governor of Wisconsin, Robert M. LaFollette signed a bill of which he was particularly proud:

The statute prohibits such lobby agents or counsel from having any private communication with members of the legislature upon any subject of legislation. The lobby is given the widest opportunity to present publicly to legislative committees, or to either branch of the legislature, any oral argument; or to present to legislative committees or to individual members of the legislature written or printed arguments in favor of or opposed to any proposed legislation; provided, however, that copies of such written or printed arguments shall be first filed in the office of the secretary of state. This law rests upon the principle that legislation is public business and that the public has a right to know what arguments are presented to members of the legislature to induce them to enact or defeat legislation, so that any citizen or body of citizens shall have opportunity, if they desire, to answer such arguments.Since I came to the United States Senate I have steadfastly maintained the same position. Again and again I have protested against secret hearings before Congressional committees upon the public business. I have protested against the business of Congress being taken into a secret party caucus and there disposed of by party rule; I have asserted and maintained at all times my right as a public servant to discuss in open Senate, and everywhere publicly, all legislative proceedings, whether originating in the executive sessions of committees or behind closed doors of caucus conferences.

I can imagine two rebuttals to LaFollette's argument. One is that people ought to be able to petition elected officials secretly, because disclosure can have a chilling effect. For example, in the present climate, Members of Congress might be less likely to meet with Muslim groups if they had to reveal every meeting. But Muslim groups, like all groups, have a constitutional right to petition the government for redress of grievances.

Tester's schedule shows meetings with many mom-and-apple-pie associations, such as "parents of children with disabilities" and the "Inter-Tribal Bison Cooperative." It is conceivable that he wouldn't want to show contacts with more controversial organizations and would therefore refuse to see them at all.

The second argument is that secrecy actually protects elected officials from undue pressure from lobbyists. Senator William Packwood (R-OR) once said:

Common Cause simply has everything upside down when they advocate 'sunshine' laws. When we're in the sunshine, as soon as we vote, every trade association in the country gets out their mailgrams and their phone calls in twelve hours, and complains about the members' votes. But when we're in the back room, the senators can vote their conscience. They vote for what they think is the good of the country. Then they can go out to the lobbyists and say: 'God, I fought for you. I did everything I could. But Packwood just wouldn't give in, you know. It's so damn horrible'." (Quoted in Birnbaum and Murray, p. 260)

Both rebuttals presume that politicians are well-intentioned and will behave better in secret than they do in public. In fact, that is occassionally true. But on balance, I think we'd be better off if Members of Congress felt they had to disclose all their meetings. Requiring such disclosure would probably violate the First Amendment. But making a habit of it would be a good thing. Tester and Gillibrand have, at the least, launched a worthy experiment.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:49 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 2, 2007

campaign finance: defining deviancy down

It isn't easy to regulate or control money in politics. There are practical problems: money tends to seep around legal limits. There are big political obstacles: everyone who holds elected office won the last race under the existing system and has an interest in preserving it. And there are constitutional objections. Even if one feels that the First Amendment allows the government to limit direct contributions to candidates, independent communications still constitute protected free speech.

Nevertheless, the government should not be for sale. We should feel at least some discomfort every time private funds flow into accounts that benefit candidates for public office. If politicians are a little embarrassed to rely on wealthy donors, there is at least a check on their behavior--a felt need to set limits or make amends. We can thereby retain a sense that the market and government are separate spheres of justice.

But shame now seems to be antiquated. According to Adam Nagourney in the New York Times (January 9):

Over 400 people, including corporate executives, governors, wealthy Republican donors and party operatives, gathered around telephones and computer screens stretched out over a huge convention center room for a day of public fund-raising on behalf of Mitt Romney, the former Massachusetts governor who created a presidential exploratory committee last week. Television camera crews and reporters circled the room as Mr. Romney's aides provided a running tally of how much had been raised.For Mr. Romney, this high-tech fund-raiser, with new fund-raising software rolled out to mark the occasion, amounted to a public declaration for the White House, as he marched out with his family for his first major event since leaving the Statehouse.

And as Mr. Romney announced at day's end that he had drawn a $6.5 million one-day haul in cash and commitments, it was also a striking example of just how important fund-raising has become as a test for presidential viability, this year more than most, with the race dominated by high-profile candidates, most of whom are unlikely to participate in the public financing system.

''This has never been done before,'' Mr. Romney said, standing in the middle of an elaborate set, a wireless microphone planted on his body. ''This is the most advanced technology ever employed as a fund-raising effort.''

Instead of announcing his presidential campaign in front of Bunker Hill or the USS Constitution, the former Massachussets governor deliberately chose a bank of fundraisers as a symbolic backdrop. In this presidential season, privately-funded campaign spending is expected to top $1 billion for the first time. The only hope is that such blatant, unashamed mixing of money and politics will provoke revulsion.

[p.s., I note that Senator Obama, who will certainly raise plenty of cash, has imposed a limit on himself. He won't take money from registered federal lobbyists. That is hardly an adequate solution to the overall problem, but it reflects an old-fashioned sense that private money is problematic in politics.]

Posted by peterlevine at 10:08 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

February 1, 2007

the hookup culture (II)

In a comment to yesterday's post on the "hookup culture," Mike Weiksner asks whether this is a new phenomenon. I don't know for sure, but I find two trends interesting: the rate of sexual intercourse is basically flat, but the percentage of adolescents who "never date" has almost doubled. (Trends are shown for 12th graders.)

This graph is consistent with the idea that "hooking up" is replacing "dating." But it raises several questions that I cannot answer without obtaining direct access to the data. (It would also be very useful to add other survey items.) What proportion of the young people who "never date" have sex? What would the trend look like for sexual behavior other than intercourse? What are the mean numbers of sexual partners for those who do and do not "date"?

Posted by peterlevine at 2:13 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack