« July 2006 | Main | September 2006 »

August 31, 2006

being smart as well as quick

It's pretty obvious that the Bush Administration will try to counter public dissatisfaction with the Iraq war by calling critics "appeasers," "quitters," and the like. It is also obvious that the national Democrats, having gone through the Swift Boat Experience, are now ready to counter-punch speedily. But will they respond cleverly?

After Secretary Rumsfeld's VFW speech, the House Democratic leader, Nancy Pelosi, was ready with a zippy quote. She said, "Secretary Rumsfeld's efforts to smear critics of the Bush administration's Iraq policy are a pathetic attempt to shift the public's attention from his repeated failure to manage the conduct of the war competently."

This reminds me a little of the press releases Mary Matalin used to issue on behalf of George H.W. Bush in 1992. She would call the Democrats "sniveling," "pathetic," "cowardly." Her rhetorical style, in other words, was to rely exclusively on pejorative adjectives. You can imagine people looking over a first draft in Pelosi's office and saying, "Let's add 'reprehensible' there." "No, 'abhorrent' sounds tougher." "Too fancy. How about 'pathetic'?"

Matalin's candidate, as you will recall, lost. If you're going to counter-punch, you have to say something that makes people stop and think. It has to have some content. For example: "No Democrat wants to 'appease' Osama bin Laden. We want to destroy him. By the way, why is bin Laden still at large, Secretary Rumsfeld?" Or: "Instead of going to Nashville to reminisce about World War II, Secretary Rumsfeld should be back in his office trying to figure out how to end the war he started."

This is not a kind of politics that inspires me. But it's going to happen, and it might as well be effective.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:45 PM | Comments (4) | TrackBack

August 30, 2006

ACLU v NSA, on appeal

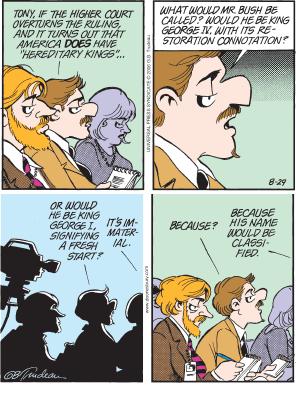

Maybe it's because I still have a summer 'flu and a fever, but I find this very funny:

Posted by peterlevine at 7:00 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 29, 2006

new thoughts on canvassing

Dana Fisher's book, Activism, Inc.: How the Outsourcing of Grassroots Campaigns Is Strangling Progressive Politics in America, is about to appear with a blurb from me on the back cover:

For idealistic young progressives today, there is basically only one paid entry-level job left in politics: canvassing. Dana R. Fisher is the first to study this crucial formative experience. Essentially, she finds that the canvass is an alienating and undemocratic experience. As a result, we are squandering the energy and ideas of a whole generation. What's more, a progressive movement that relies on regimented canvassing is doomed to defeat because it lacks an authentic connection with citizens. Unless we take seriously the rigorous evidence and acute arguments of Activism, Inc., the future looks grim.

My conscience is bothering me for two reasons. First, my summary of Fisher's book is a pretty strong statement, perhaps exaggerating what she says. Second, she does tell a highly critical story (as her subtitle indicates). My blurb lends my authority to her criticism, suggesting that her "rigorous" and "acute" scholarship must be true. In fact, given what little I know directly about canvassing, plus the evidence that Fisher presents in her book, I cannot say whether her account is accurate or not.

Fisher makes three main points:

1) Canvassing is bad for canvassers: many are burnt out, stuck in dead-end positions, or alienated because they have to raise money by reciting �scripts� that they do not fully understand.

2) Canvassing for progressive causes is being centralized into a few big, multi-purpose operations. This consolidation reduces the connection between the canvassers and the various lobbies for which they raise money.

3) Canvassing is bad for democracy, because professional activists set the progressive political agenda and lobby using money from people whom they have mobilized through one-way conversations. Democracy needs organizations in which citizens frame their own agendas through conversations, develop working relationships with peers and neighbors, and then hold professional lobbyists and leaders accountable. (This third point is mentioned but not developed in the book; it's partly my own extrapolation.)

The first point--that canvassing is bad for canvassers--is based on Fisher�s 115 interviews. She provides many quotes, which actually tell a mixed story. Some of the interviewees have positive things to say; some are critical of the canvass. She does not code the interviews so that she can provide statistical summaries (such as "55% were negative"), but she does use words like "most."

I don't think the lack of statistics matters. Selecting and coding interviews is a fairly subjective process, so any hard numbers would look more precise than they would actually be. In essence, we must rely on Fisher to generalize fairly and accurately from her own observations. The fact that she quotes people who have a positive view of canvassing could be taken as evidence that she is scrupulous and balanced. Or the fact that she draws very negative conclusions, despite having talked to people whose views were positive, could be taken as a sign that she exaggerates.

Overall, she could be right. Others have made similar claims.* However, she could also be wrong, and I know former canvassers who loved their jobs. I am uncomfortable about having endorsed her portrayal with a confidence that cannot be sustained from reading the book alone.

Incidentally, this is qualitative research, which I strongly support. I have a doctorate in philosophy, which is about as qualitative as you can get. But it's unusual for a qualitative study to focus on one real organization and to be highly negative. (Fisher uses a pseudonym, but the real identity of the canvass is not hard to discern.) If you criticize a sector or a profession, you must try to be accurate. But if you criticize an identifiable organization, the stakes are higher.

In this respect, Fisher's book is more like a work of investigative journalism than typical qualitative social science. Aggressive journalism is extremely valuable--no less worthy than scholarly research; but it has different norms. We realize that the reliability of a reporter depends on his or her judgment, experience, and ideological bias: reporters lack a fancy "methodology" that they can use to defend their conclusions. Furthermore, journalists feel free to tell unusual stories and to seek out atypical cases "man bites dog." In contrast, most qualitative research is an attempt to generalize on the basis of a representative sample. Much attention goes into methods for constructing representative samples of quotations taken from representative informants. These methods of selection are the basis of the researcher�s legitimacy.

By endorsing the "rigor" of Fisher's book, I implied that her summaries were based on representative comments by representative canvassers. In fact, I don't have any way of knowing whether that is the case.

Despite my blurb, I really cannot say much about the second major claim of the book: that consolidating the canvassing "business" into one or a few big operations has worsened the impact on canvassers. As a theoretical point, we would expect monopolies to be bad in this field, as in any other. However, there is not much evidence in the book about the degree to which canvassing has consolidated, nor about the the impact of outsourcing on the groups that have chosen to pay for canvassing.

Fisher's third point is that canvassing is bad for democracy. Here she relies on a critique of modern American politics that comes from authors like Harry Boyte, Theda Skocpol, Carmen Sirianni, Lewis Friedland, Robert Putnam, Marshall Ganz, Mark R. Warren, Gregory Markus, and Kevin Mattson, among others. Allowing for major and interesting differences among these authors, they all decry "mailing-list" organizations that simply ask citizens to pay for professional advocacy work. They see these organizations as a new elite that lacks an authentic base.

Several also lament a tendency to mobilize citizens by demonizing opponents. They argue that this approach makes it more difficult actually to solve problems. Boyte, for example, has written: "The canvass embodies a view of politics as a zero-sum struggle over scarce resources pitting the forces of innocence against the forces of evil. In citizen action groups like ACORN or Clean Water Action or the PIRGs, narrowly scripted issue campaigns and a rigid ideological stance dominate. Public leadership development that teaches students to understand the narratives and interests of those with whom they disagree is slighted. The open, diverse political atmosphere of places in the Hull House tradition disappears."

We know that Americans' average rate of group membership has stayed constant since the 1970s, yet people's tendency to work with others on community problems and their frequency of attending meetings (as measured in surveys) have dropped precipitously. It could be that centralized, national organizations displace forms of politics in which people set their own agendas and act cooperatively. Boyte, Sirianni, Skocpol, Warren, and Markus, in particular, argue that we need the kind of "relational organizing" exemplified by the Industrial Areas Foundation, Pico, and Gamaliel. Those groups depend on long-lasting, face-to-face relationships, horizontal communication among members, local cultural norms, and open-ended deliberation.

Relatively little in this literature is explicitly about canvassing--let alone about the specific canvass that Fisher studied. Thus the question is whether canvassing exemplifies the problem of professionalized, "mailing-list" organizations. Fisher sees canvassers as tools for delivering one-way messages to potential donors. However, if canvassers engage in two-way conversations on people's doorsteps and pass the word back to their bosses, then canvassing is better for democracy than mass mailings are. Again, everything depends on the accuracy of Fisher's first claim about the canvassing experience.

Fisher's book raises questions that I am not qualified to settle about the performance of a particular group. That's unpleasant because it pits her character against theirs. I'm inevitably implicated because I know and have professional connections to both sides. However, there are also more constructive and tractable issues to consider. For example:

There has been a decline of chapter-based, strongly participatory, locally-rooted organizations that were once accountable to their members. (I am referring to the old political parties, unions, fraternal and sororal organizations, VFW, PTA, and the like.) Did the rise of mailing-list organizations contribute to that problem, or do they represent a separate phenomenon altogether? Is canvassing typically the same as "mailing-list" politics? Or is it considerably more interactive? Is there an essential conflict between the kind of canvassing operations associated with Ralph Nader, on the one hand, and the "relational organizing" of IAF, Pico, and Gamaliel, on the other? Or can they be synergistic? Would it be possible to increase the degree of interactivity, accountability to members, and horizontal communication within a canvass operation without undermining its effectiveness at raising money and lining up supporters? Could canvassing actually be made more effective if it became more democratic?

*See, e.g., Kevin Mattson (opens a PDF--look at p. 21), Greg Bloom, and Nathan Wyeth

Posted by peterlevine at 3:40 PM | Comments (4) | TrackBack

August 28, 2006

Fahrenheit 102°

I like to post here every work day, but a 'flu that has been going around our family has hit me, and I'm too feverish to think straight. Having checked my email, I'm going back to bed.

Posted by peterlevine at 4:55 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 25, 2006

another argument for redistricting

Growing up in a politically competitive community turns out to have important educational advantages. Gimpel, Lay, and Schuknecht find that young people who live in communities with competitive elections are more knowledgeable about politics, more confident in their own capacity to make a difference, more trusting in government to be responsive, more tolerant, and more likely to discuss politics than their peers, holding many other factors constant.

Competition probably enhances civic learning because politicians and parties must reach out to citizens when elections are close. They reach out with messages that make people feel important and that convey interesting information. Also, regardless of how politicians behave, one can learn from growing up among roughly equal groups of Democrats and Republicans. In politically diverse communities, young people are exposed to divergent political views and understand that disagreement is inevitable. (The same advantage also arises from religious diversity.)

Political competitiveness can compensate for economic disadvantage. In fact, Gimpel and colleagues found that in poor communities with a mix of Democratic and Republican voters, young people grow up more knowledgeable than their peers who live in wealthy, single-party suburbs. Political competition boosts the level of discussion "by an amazing 17 percentage points among those with no plans to attend college," because exposure to robust politics compensates for their relatively poor formal educations.

However, most Americans do not grow up in competitive districts. Only four incumbent Representatives were defeated in 2002, and only five in 2004. The same pattern occurs in many states. For example, in 2004, none of California's 153 legislative seats changed parties. The 2006 elections are expected to be more competitive than usual. Yet even a loss of 15 Republican seats in 2006 would represent only 3.4 percent of the House of Representatives.

One reason for the lack of competition is that districts have been drawn with increasing sophistication to favor one party over the other. But communities have also become more politically homogeneous. No one redraws county lines to benefit politicians, yet the segregation of Democrats and Republicans at the county level increased by 47 percent during the last quarter of the 20th century. This is a bad sign for the next generation of citizens.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:03 PM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

August 24, 2006

how to respond to the terror risk

A diverse range of people are arguing that we have overreacted to terror threats after 9/11. Their arguments include the following:

The statistical risk of being killed by a terrorist is very low. As John Mueller writes in a paper for the libertarian Cato Institute (pdf), "Even with the September 11 attacks included in the count, the number of Americans killed by international terrorism since the late 1960s (which is when the State Department began counting) is about the same as the number of Americans killed over the same period by lightning, accident-causing deer, or severe allergic reaction to peanuts." Responses to terror, however, can be very costly. Consider the price and inconvenience of airport screening procedures. Or the deaths caused when people drive instead fly because they are afraid of terror. Or public support for the Iraq war. Acting terrified of terror encourages terrorists. It means that they can damage America simply by talking about plots. There is an emerging "we-are-not-afraid" movement that argues we ought to react to terrorist threats in a calm and unruffled manner. The alleged British bombing plot probably shows a desire to blow up airplanes, but the conspirators may have been far from being able to pull off the terror of which they dreamed. (Phronesisaical has links.) Fear of terror steers public resources to certain agencies and companies that have an incentive to stoke the fear further. Irrational fear of terror distorts public opinion, to the advantage of incumbent politicians. Some see evidence of Machiavellian manipulation; but Mueller draws a more cautious conclusion: "There is no reason to suspect that President Bush's concern about terrorism is anything but genuine. However, his approval rating did receive the greatest boost for any president in history in September 2001, and it would be politically unnatural for him not to notice. ... This process is hardly new. The preoccupation of the media and of Jimmy Carter’s presidency with the hostages taken by Iran in 1979 to the exclusion of almost everything else may look foolish in retrospect. ... But it doubtless appeared to be good politics at the time--Carter's dismal approval rating soared when the hostages were seized."

I think these are good points, but there is another side to consider. It's unreasonable to adopt a strictly utilitarian calculus that treats all deaths as equally significant. Every human being counts the same, yet we are entitled to care especially about some tragic events. If deaths were fungible, then none would really matter; they would all be mere statistics.

In particular, as a nation, we are entitled to care more about the 2,700 killed on 9/11 than about the roughly similar number of deaths to tonsil cancer in 2001. Pure utilitarianism would tell us that 9/11 happened in the past; thus it's irrational to do anything about it, other than to try to prevent a similar disaster in the future. And it's irrational to put resources into preventing a terrorist attack if we could prevent more deaths by putting the same money and energy into seat belts or cancer prevention. However, the attack on 9/11 was a story of hatred against the United States, premeditated murder, acute suffering, and heroic response. Unless we can pay special attention to moving stories, there is no reason to care about life itself.

In my view, we can rationally respond to 9/11 by bringing the perpetrators to justice, even at substantial cost, and even if they pose no threat. That violates the utilitarian reasoning that underlies Mueller's argument. However, note that the Bush administration has not brought Bin Laden to justice. Also note that the 9/11 story may justify vengeance, but it does not justify excessive fear about similar attacks.

Finally, we must think carefully about responsibility. On a pure utilitarian calculus, we might be better off with virtually no airport security. A tiny percentage of people would be killed by bombers, because there aren't very many terrorists with the will and the means to kill. By getting rid of airport screenings, we would save billions of dollars and vast amounts of time, and possibly even save lives by encouraging more people to fly instead of drive. But this reasoning doesn't work. If a government cancelled airport screening procedures, some people would die, and it would not be irrational to pin the responsibility for those deaths on the government.

Thus no government can dismiss the terror threat, because people understandably hold the national security apparatus responsible for protecting them against terror. In contrast, protection against tonsil cancer is not seen as a state responsibility. I like the following passage by Senator McCain (quoted in Mueller), but I'm not sure that any administration could get away with using it as an anti-terror policy:

Get on the damn elevator! Fly on the damn plane! Calculate the odds of being harmed by a terrorist! It’s still about as likely as being swept out to sea by a tidal wave. Suck it up, for crying out loud. You’re almost certainly going to be okay. And in the unlikely event you’re not, do you really want to spend your last days cowering behind plastic sheets and duct tape? That’s not a life worth living, is it?

Posted by peterlevine at 10:17 AM | Comments (5) | TrackBack

August 23, 2006

citizen news projects

People frequently send me links to websites on which citizens (not professional journalists) present local news. Two recent examples from my inbox:

Corpus Beat is an impressive site from Corpus Christi, TX, with news articles, blogs, photo competitions, and organizational charts of local government, among other features. Much of the content seems to be created by local kids. I especially liked a series of interviews of local officials and a feature called "Brain Gain," about how to prevent college-educated young people from leaving the area. All the articles for "Brain Gain" were written by students. In keeping with classic public journalism experiments from the 1990s, Corpus Beat convened a forum on the brain drain problem and reported the results--thereby prompting public deliberation and covering it as news.

Much closer to (my) home, College Park, MD now has a well-written, independent blog about local issues. Rethink College Park has two staffers but is open to adding more.

Posted by peterlevine at 4:11 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 22, 2006

two dates to save

OCTOBER 3: CIRCLE TO RELEASE NEW COMPREHENSIVE SURVEY OF YOUTH CIVIC ENGAGEMENT

At the National Press Club in Washington, DC on October 3, from 9:30-11 am, CIRCLE will release findings from a major survey that includes numerous indicators of youth engagement as well as information about youth attitudes toward various social and political issues. This survey will update and expand the Civic and Political Health of the Nation Report, published in 2002.

Following the press conference, which is open to the public, CIRCLE will hold a first-ever "Practitioners' Forum" from 11-2:30 to discuss practical implications of the new findings. There will be small group discussions on topics such as:

Youth Political Engagement and Trust in Government The Civic Engagement of Immigrant Youth Youth Community Service and Volunteerism Tolerance and the Youth Generation

This will be an opportunity to influence how youth civic engagement is measured in the future and to inform CIRCLE's efforts to connect research and practice.

The Practitioners' Forum will include a lunch, and there will be limited space available. Please RSVP by September 22nd to Abby Kiesa, Youth Coordinator at CIRCLE, at akiesa@umd.edu.

SEPTEMBER 18: NATIONAL CONFERENCE ON CITIZENSHIP (NCoC) TO RELEASE 'CIVIC HEALTH INDEX' REPORT

CIRCLE provided data, graphs, and analysis for an ambitious NCoC report that explores 40 key indicators of civic engagement over time. These indicators include political activity, civic knowledge, volunteering, trust, and philanthropy, among others. The report also looks separately at various segments of the US population, including youth.

The release will take place on Monday, September 18, 2006 from 10:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. at the Marriott at Metro Center in Washington, DC. Prominent speakers (Robert Putnam, Harris Wofford, and others) will address various aspects of civic engagement.

There is no charge for the event and lunch will be served. Registration is required.

Posted by peterlevine at 3:27 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 21, 2006

Iraq: the next tragedy

Daniel Byman and Kenneth Pollack's editorial in Sunday's Washington Post prompts some questions that I have not seen discussed elsewhere. Why have we not seen the long columns of refugees in Iraq that are typical of civil conflicts? What would it take to cause massive flows of refugees? In particular, would the removal of US forces cause Iraqis to throw some possessions in suitcases and start walking for the border? Who would move, and where would they try to go? What would be the consequences if hundreds of thousands or millions of civilians attempted to walk into Iran, Turkey, Jordan, Syria, Saudi Arabia, or Kuwait?

I realize that there have been population shifts already, with Iraqis moving into more homogeneous neighborhoods and some middle class folks emigrating. Byman and Pollack estimate that about half a million Iraqis have migrated in those ways. But we haven't seen the equivalent of Kosovo (72 percent of the population displaced), or Congo (7.1 percent of the population killed). Anyone--Democrat or Republican--who wants to be part of governing the United States had better figure out how to prevent mass migrations in Iraq and what to do if they begin.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:46 AM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

August 18, 2006

Erik Erikson on youthful fanaticism

Reading Erik Erikson's "The Eight Ages of Man" (1966) for other purposes last night, I came across an eerily prescient* passage on p. 290 that could describe the young British citizens who are alleged to have plotted to blow up airplanes:

Young people can also be remarkably clannish, and cruel in their exclusion of all those who are 'different,' in skin color or cultural background, in tastes and gifts, and often in such petty aspects of dress and gesture as have been temporarily selected as the signs of an in-grouper or an out-grouper. It is important to understand (which does not means condone or participate in) such intolerance as a defense against a sense of identity confusion. For adolescents not only help one another temporarily through much discomfort by forming cliques and stereotyping themselves, their ideals, and their enemies; they also perversely test each other's capacity to pledge fidelity. The readiness for such testing also explains the appeal which simple and cruel totalitarian doctrines have on the minds of the youth of such countries and classes as have lost or are losing their group identities (feudal, agrarian, tribal, national) and face world-wide industrialization, emancipation, and wider communication.

*"Eerily prescient" appears 67,000 times on the Web, according to Google, which qualifies it as a cliché. Apologies.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:10 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 17, 2006

a learning community experiment

I'm interested in the following ideas and I'm thinking about a true experiment that could help to test them:

1. Education is not just what happens to kids inside schools. A whole community should be involved in educating all of its residents. Standard educational measures (such as test scores and school completion) will improve to the degree that many people in many venues participate in education and do not leave the job to professionals in schools.

2. Kids benefit from being offered opportunities to serve their communities. They are more likely to succeed in school and less likely to engage in self-destructive behavior if communities tap their energy, creativity, and knowledge for constructive purposes.

3. A rewarding and effective form of service is to catalog the assets of a community and make them more available to residents. All communities, no matter how economically poor, have assets worth finding. When communities know their own assets, they can address their own problems better and take better advantage of outside support.

Therefore,

4. It is a promising idea to help youth to identify opportunities for learning in their communities and to make these resources available to their fellow citizens.

We're cooking up an experiment in which kids would be assisted in identifying skills and knowledge that other residents want to learn. The kids would then find opportunities for learning--formal courses and classes; educational institutions such as museums, parks, and libraries; individuals and companies that sell training; jobs with educational value; and residents who are willing to share knowledge free of charge. This project would resemble the St. Paul Neighborhood Learning Community.

Kids would enter the information in a database so that other residents could find learning opportunities on a map or by searching by topic. Some local community centers would be randomly selected to participate in the data-collection; others would not; and we would survey kids and adult volunteers in all the centers to measure the effects of participating. We would hypothesize that, in the participating centers, there would be a greater increase in measures of: academic success, understanding of community, and interest in civic participation.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:32 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

August 16, 2006

the difference between economics and psychology

To tell the truth, I have never taken a single course in either economics or psychology. However, my professional interests have led me to read a fair amount in both disciplines and to talk to scholars of both persuasions. I think I have noticed a basic difference.

Economists are interested in concrete actions: behaviors. They began by studying financial exchanges, but now they will investigate practically anything, including learning, war, marriage, and civic participation, as long as it involves observable or reportable acts. In contrast, pyschologists (since the decline of behaviorism) are interested in mental states, many of which are not directly observable. You can't see what someone's identity or mood or capacity is, nor can you necessarily ask the person directly. Pyschologists tend to measure these mental states by asking many questions or making many observations and creating statistically reliable "constructs." Thus they like to use scales and factor analysis. (See this apparently classic 1955 paper.) Economists are suspicious of such constructs because there is always an imperfect correlation between the construct and its directly measured components.

I don't think you can tell the difference between the disciplines by asking what they study: pyschologists explore human behavior in markets, and modern economists investigate practically everything. Instead, the divide is between a kind of empiricism or nominalism that distrusts general constructs, versus a kind of philosophical "realism" that takes unobserved mental states seriously.

As for political science--with apologies to my many friends in that field, it isn't a discipline at all, but rather a topic area that uses methods from economics, pychology, philosophy, and narrative history.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:38 AM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

August 15, 2006

when chivalry died

I just finished James Shapiro's very enjoyable book entitled A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare: 1599, which is about the year when Henry the Fifth, Julius Ceasar, As You Like it, and Hamlet were written. It's packed with interesting contextual information, such as this pair of facts:

1. In the year 1599, the Earl of Essex took an army to Ireland to suppress a revolt and also (his own goal) to restore English chivalry. He knighted hundreds of his followers, more than doubling the total number of Englishmen who held titles; challenged the Irish rebel Tyrone to single combat; held great heraldric feasts; and explicitly called for a revival of the nobility and its virtues. By the end of the year, he was under house arrest and awaiting execution. Essex's feudalism was fundamentally incompatible with the unitary, professionalized, plenipotentary state that Elizabeth managed.

2. The same year, London merchants organized the East India Company and sent an expedition to Asia, thereby launching the British Empire. The Company and its expedition were run by the bourgeoisie; nobles were excluded from management.

You can never tell from reading the words of Shakespeare's characters what he thought about anything. But Shapiro suspects that he was basically reactionary, in the sense that he preferred the disappearing world of chivalry to the new one of bourgeois trade and industry. Shakespeare could think his way into the minds of characters, both good and bad, who were martial, heroic, grandiloquent, and noble. He could conjure scenes of pomp, ceremony, and heraldry. He also presented some bourgeois scenes, for example in The Merchant of Venice and Romeo and Juliet. But his bourgeois characters were far less memorable and developed than Hamlet, Lear, and their kingly company.

At first it seems surprising that a revolutionary writer should have held reactionary historical views. But Shakespeare was most innovative in his ability to represent the inner lives of diverse people. It was his breakthrough to show the private thinking of great public figures--to supply complex and ambiguous motives for acts of state. Perhaps to represent the interior lives of private people was not yet possible in 1599; bourgeois culture had first to develop.

Posted by peterlevine at 2:31 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 14, 2006

moderation

I don't have a firm opinion about whether Ned Lamont's victory in last week's Connecticut primary was good or bad news. However, as someone whose job is to study deliberative democracy, civil society, and related issues, I would like to address the thesis that Senator Lieberman's "moderation" was good for democracy.

"Not necessarily," is the short answer. I think one's position on the political spectrum is independent of one's impact on deliberation and the political culture. Moderates are no more likely to help the quality of our politics than are liberals or conservatives.

It's worth recalling what kind of political debate we need:

1. We need choices among real alternatives. Sometimes, citizens are better served by relatively sharp choices than by a mushy middle. Also, it can be better for leaders to be motivated by strong principles than by mere party membership. Some people's principles happen to land them in the center of the current American political spectrum, and that's fine. But other politicians head for the center because they want to attract the median voter, not because of any principles that they can defend in public discussions.

I don't know why (or whether) Senator Lieberman has been a centrist, but I do welcome the debate sparked by the Connecticut primary. As Eli Pariser, executive director of MoveOn.org, said, "I think because the Connecticut primary was driven by real, deep issues that our nation should be grappling with, it's exactly what our politics ought to be like, rather than nasty, gotcha bickering. ... It was about big ideas and big challenges facing the country."

2. Although we want real alternatives, we don't want partisan animosity to rise to the level that members of the rival parties cannot cooperate, even when they happen to share the same principles (as they often do). Legislatures pass more bills when there is more "comity," which can be defined as an ability to cooperate on topics that do not provoke ideological disagreement. Thus, to my fellow progressives who want Democrats to play more aggressively, I would say that's not a path to passing progressive legislation. Without some Republican support, nothing will pass.

On the other hand, there is no reason to believe that moderates are always better at comity than strong liberals and conservatives. Some moderates (the ones who are hunting for the median voter) may be so strategic that they shun cooperation when they think they can score partisan points or make the other team look bad. Conversely, some real ideologues are so motivated by principle that they are happy to work with members of the opposite party when they see common ground. An example is Bob Barr, the right-wing former US Representative, who works well with civil libertarians because they share a skepticism about government. Senator Kennedy, despite a reputation for liberalism, is famous for working with Senator Hatch and others on the Republican side.

3. We need free and frank criticisms of the public performance of people in power. For example, criticizing the Bush Administration's handling of Katrina, the budget, or Iraq does not harm democracy, deliberation, or civic engagement. On the contrary, it is wrong to try to shut down such criticism by suggesting that it helps terrorists. On the other hand, we don't want people to commit the ad hominem fallacy, which is to reject an idea because those who defend it are flawed in some way (e.g., hypocritical or incompetent). Nor do we want criticism to focus on politicians' private lives and private views, because that can simply discourage good people from entering public life. (Besides, we usually have very unreliable information about people's private opinions.)

It's not obvious to me that moderates are less likely than radicals to use ad hominem arguments. Senator Lieberman has used as many as Mr. Lamont.

4. We need to hold politicians accountable for what they promise on the campaign trail. On the other hand, we want them to be able to learn, listen, evolve, and negotiate after they are elected. Thus we shouldn't go hunting for inconsistencies in their records as if those were always signs of bad faith.

Again, it's not obvious that moderates are less likely to play "gotcha" when they spot changes in their opponents' records. Maybe there is a pattern, and maybe there isn't. Regardless, we know that some strong ideologues are also good deliberators who focus on issues, not personalities, and who allow their opponents to evolve. That means that moderation is not good in itself.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:10 AM | Comments (4) | TrackBack

August 11, 2006

the magic dragon

I spent most of today in the kind of meeting that is most familiar to me. People in suits sat around a large, open table in an office inside the Washington Beltway, explaining what their alphabet soup of professional organizations think about No Child Left Behind and related topics. The terminology and style of the whole event was absolutely typical--with one big exception. The organizer was Peter Yarrow, the "Peter" of Peter, Paul and Mary. Dressed in a bright blue shirt and carrying his guitar, he stood in the middle of the absolutely standard DC conference room and started the meeting with a chorus of "Puff the Magic Dragon." I would call it a "rousing chorus," except that many of the education wonks were lip-synching. We also got to hear "Don't Laugh at Me," which is the theme song of Operation Respect, and several other Yarrow originals.

Posted by peterlevine at 6:29 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

August 10, 2006

a cautionary tale

John Dewey and his contemporaries in the Progressive Era invented many of the standard forms of civic education, including social studies courses, student governments, service clubs, scholastic newspapers, and 4-H. Dewey rightly argued that "Formal instruction ... easily becomes remote and dead--abstract and bookish, to use the ordinary words of depreciation." He favored experiential education for democracy and tried to "reorganize" American education "so that learning takes place in connection with the intelligent carrying forward of purposeful activities." A good example would be a school newspaper, which requires sustained, cooperative work, promotes deliberation, and depends upon perennial values such as freedom of the press.

As Diane Ravitch writes in The Troubled Crusade (1983), Dewey saw educational reform as a "vital part" of a broader "social and political reform movement" that aimed at richer and more equitable political participation. Thus Dewey and his fellow progressives sought better civic education while they also battled corruption, pursued women's suffrage and civil rights, and launched independent political journals for adults. They saw civic experiences in school as means to help students begin participating in the serious business of democracy, which also needed to be reformed.

Unfortunately, the specific innovations that the progressives introduced into schools--scholastic newspapers, debate clubs, social studies courses, and the like--could easily lose their original connection to democracy. When that purpose was forgotten or ignored, extracurricular activities and social studies classes became means to impart good behavior, academic skills, or "social hygiene"--not ways to begin changing society.

Soon, Ravitch writes, "the progressive education movement became institutionalized and professionalized, and its major themes accordingly changed. Shorn of its roots in politics and society, pedagogical progressivism came to be identified with the child-centered school; with a pretentious scientism; with social efficiency and social utility rather than social reform; and with a vigorous suspicion of 'bookish' learning."

Today, there is a serious risk that we could repeat the same pattern. For example, excellent service-learning programs enhance students' civic capacity: they increase skills and motivations for self-government. The best programs allow students to tackle problems that really matter, sometimes provoking controversy. But service-learning is being widely advocated as a way to reduce teen pregnancy or drug abuse and as an alternative to "bookish" academic curricula for students who are not succeeding in school. There is merit in both rationales, but there is also the danger that service-learning will be watered down and depoliticized. To use Ravitch's terms, service-learning can be shorn of its connection to politics, made overly "child-centered" (instead of academically challenging), and used to enhance "social efficiency" (e.g., to lower rates of delinquency) as recommended by behavioral scientists.

The alternative is to recall that schools are public spaces in which young people begin the serious business of self-government and have early opportunities to pursue social change. Although it is helpful to consult scientific studies, students and other community members must decide for themselves what social causes they favor. (No "pretentious scientism"!) Service-learning, civics courses, and extracurricular activities are useful means for democratic education, but they are not ends in themselves. The point of the whole business is democracy, which begins in school and not after graduation.

Posted by peterlevine at 1:32 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 9, 2006

a new survey of youth entertainment culture

An interesting LA Times poll of American kids (age 12-24) finds them bored despite a plethora of electronic entertainment devices. "'I feel bored like all the time, 'cause there is like nothing to do,' said Shannon Carlson, 13, of Warren, Ohio, a respondent who has an array of gadgets, equipment and entertainment options at her disposal but can't ward off ennui."

I like Reed Larson's idea that adolescents lack opportunities for "initiative," which he defines as voluntarily choosing a task and then planning and sustaining it over time. Kids choose their entertainment, but needn't plan or sustain it. They are supposed to sustain interest in their school projects, but they don't choose them. For Larson (a pyschologist), the lack of opportunities for "initiative" explains frequent reports of boredom. Service projects and other forms of civic engagement are important alternatives.

The LA Times poll also challenges some myths about young Americans. For example, more than twice as many said that they had voted in a real election as said they had voted for an American Idol candidate. Even accounting for some "response bias" (i.e., kids may feel that they ought to say they voted in a real election), that's still a refutation of the cliche that youth are only interested in pop culture.

Posted by peterlevine at 1:59 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

August 8, 2006

listening to Kansas

In today's New York Times, the author of What's the Matter with Kansas? Thomas Frank, decries the right-wing revolt against expertise:

To the faithful, theirs is a war against 'elites,' and, with striking regularity, that means a war against the professions. The anti-abortion movement, for example, dwells obsessively on the villainy of the medical establishment. The uproar over the liberal media, a popular delusion going on 40, is a veiled reaction to the professionalization of journalism. The war on judges, now enjoying a new vogue, is a response to an imagined 'grab for legislative power' (as one current Kansas campaign mailing puts it) by unelected representatives in the legal profession. And the attack on evolution, the most ill-conceived thrust of them all, is a direct shot at the authority of science and, by extension, at the education systen, the very foundation of professional expertise.

Frank finds all this very distressing, because he believes that the "populist" activists of Kansas are undermining their own self-interests by voting against professionals--thereby achieving "distinctly unpopulist results."

The question turns on whether professionals are actually worthy of trust and support. If Kansans are furious at "education insiders" and other experts, is that because they have been deluded by conservative rabble-raisers? Or could they have a point about professionals' arrogance?

Consider that Americans (parents and other non-professionals) play a dramatically reduced role in public education. In the 1970s, more than 40 percent said that they worked on community projects--which often involved education--but that percentage is now down to the 20s. PTA membership rose to 45 per 100 families in 1960, but then fell to less than half of that in the last twenty years. Under No Child Left Behind, very little about schools can be influenced or debated except evolution and sex ed: two hot-button issues that mobilize ideologues. The core curriculum, which is loaded with value-judgments that deserve public debate, has been decided by the people who write tests--pyschometricians and other experts far from Kansas (but close to Princeton, NJ). Meanwhile, the general atmosphere of schools seems commercialized, sexualized, and otherwise reflective of bad values.

Anyone who has tried to participate in educational issues, whether at the national level or in one's local school, knows that jargon, turf, and bureaucracy are the order of the day. This would be fine if school systems produced excellent results.

I have dwelled on the case of education, but it would not be difficult to develop similar arguments about professional journalism and medical care. (Anyone who has wrestled with the medical bureaucracy during a health emergency will recognize an arrogance, a status-consciousness, a worship of machines and chemicals, and a lack of concern for the whole patient that cannot be attributed to insurance issues alone.) I know it is more controversial, but I tend to believe that judges have overstepped their bounds as well, particularly in cases where they have made live public debates moot by handing down decisions not clearly based in the Constitution.

In short, I think Frank very acutely diagnoses a revolt against the professional elites. But suppressing the revolt will not make the problem go away. Professionals must change their behavior in order to merit public respect.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:34 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 7, 2006

"slave trader ... patriot"

I'm in Providence, RI. Walking past a fine eighteenth century house, I spotted a plaque with these words:

Also shown on the plaque is the seal representing a soldier of The First Rhode Island Regiment (1778)--"The Black Regiment."

It's a striking juxtaposition. The house of slave trader is decorated or even honored with a plaque purchased by an African American heritage society. John Brown's "position" is attributed to the money he made from the transatlantic slave trade. But he is also called a "patriot."

As a member of the Continental Congress and early House of Representatives, Brown was a founder of the United States. He was also a founder of Brown University. The source of his funds--hence his "position" in society, which made him a leader--was deeply immoral. Yet the United States Government and Brown University benefit all Americans. Of course, that's easy for me to say, because I have had access to such institutions all my life and have benefited from them. (I've never had anything to do with Brown--but other private universities have given me various advantages.) Most people are born in positions from which it is very hard if not impossible to reach the Ivy League. It's always worth asking whether, from behind a veil of ignorance, one would choose to have institutions like Brown University. Brown's particular moral origin prompts that question but does not settle it. Perhaps the source of the funds is irrelevant. Or perhaps dirty money is mixed with good in all great institutions.

I had some of these thoughts as I sat, a few minutes later, in the pure interior of Roger Williams' First Baptist Church (actually built 150 years after his time, in 1774-5). Williams denied the English King's right to appropriate American land and carefully bought Providence from the native Narragansetts. It was a promising start and it led to a beautiful and dignified city--but one in which men had "lucrative careers" selling other people's lives.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:16 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 4, 2006

Calvino's free hyper-indirect discourse

I recently finished Italo Calvino's If on a Winter's Night a Traveler, in William Weaver's translation. It's a novel about trying to read a novel of that name by Italo Calvino--a difficult and even perilous task, since the book is constantly being mixed up with others, stolen, or fraudulantly exchanged. Ten of the chapters are the beginnings of novels that the protagonist ("you") try to read, hoping that they are continuations of what you have read so far. Each is a parody of a particular type of literature and a genuinely suspenseful story that breaks off just when your interest is most aroused.

Calvino's writing has an aspect that I have never seen before, although it could be viewed as a radical extension of "free indirect discourse." That is the technique of describing something in the omniscient third person, but in such a way that it seems to take on the perspective and language of a character within the book. A famous example from Austen's Emma:

She had ventured once alone to Randalls, but it was not pleasant; and a Harriet Smith, therefore, one whom she could summon at any time to a walk, would be a valuable addition to her privileges. But in every respect as she saw more of her, she approved of her, and was confirmed in all her kind designs.Literally, that is the narrator's description of Harriet Smith mixed with some of Emma's thoughts--but the two are inseparable. The whole narration is suffused with Emma's voice. It is Emma, for example, who sees Harriet as "not clever." Emma's patronizing attitude is presented with delicious irony.Harriet certainly was not clever, but she had a sweet, docile, graceful disposition; was totally free from conceit; and only desiring to be guided by anyone she looked up to. Her early attachment to herself was very amiable; and her inclination for good company and power of appreciating what was elegant and clever, shewed that there was no want of taste, though strength of understanding must not be expected. Altogether she was quite convinced of Harriet Smith's being exactly the young friend she wanted -- exactly the something which her home required.

Calvino takes this technique a step further. He describes what books would be like if they told particular stories. He uses such descriptions of imaginary texts as a means of story-telling. Examples:

A fight scene from the chapter entitled "Outside the Town of Malbork (p. 39): "The page you're reading should convey this violent contact of dull and painful blows, of fierce and lacerating responses; this bodiliness of using one's own body against another body ..." As you read about the description of a fight, you visualize the actual struggle--but through the eyes of a book that Calvino regards with irony.

From Calvino's parody of Magical Realism entitled "Around and Empty Grave": p. 225: "I pass through a series of places that ought to be more and more interior, whereas instead I find myself more and more outside; from one courtyard I move to another courtyard, as if in this palace all the doors served only for leaving and never for entering. The story should give the sense of disorientation in places that I am seeing for the first time but also places that have left in my memory not a recollection but a void."

Calvino flagrantly violates the rule that writers should show and not tell. He tells us what the story is about and thereby narrates it.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:01 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 3, 2006

back to high school

Around 1985, Eccles and Barber asked 10th graders in Michigan to identify themselves with one of the characters in the recent Hollywood movie, The Breakfast Club. All but five percent readily placed themselves in precisely one of the following categories: "jock," "princess," "brain," "criminal," or "basket case." Each type of student spent most of his or her time with others of the same self-ascribed category. Students' identities at 10th grade were strongly predictive of outcomes a decade later. The princesses attended college but drank. The criminals did drugs and dropped out. The brains were sober and successful in college. Those who participated in the performing arts did well in school but had higher rates of alcohol abuse and suicide attempts.

If we allow students to self-associate, given the norm in a modern American high school, they are likely to segregate into groups that reinforce social stratification. Students have too much choice about peer networks, but not enough obligation or opportunity to work with others unlike themselves. In various qualititative studies, including my own last year, students complain about being in a "bubble" (their word), isolated from other types of people.

If we try to build democratic communities in schools, through such concrete means as student governments, public performances, websites, or scholastic newspapers, these products will be produced by particular peer groups for their own friends. They will not benefit the student body as a whole.

This study is an argument for more radical school restructuring.

Sources: Jacquelynne S. Eccles and Bonnie L. Barber, "Student Council, Volunteering, Basketball, or Marching Band: What Kind of Extracurricular Involvement Matters," Journal of Adolescent Research, vol. 14, no. 1 (January 1999), p. 31; Bonnie L. Barber, Jacquelynne S. Eccles, and Margaret R. Stone, "Whatever Happened to the Jock, the Brain, and the Princess? Young Adult Pathways Linked to Adolescent Activity Involvement and Social Identity," Journal of Adolescent Research, vol. 16, no 5 (September 2001), pp. 429-455.

Posted by peterlevine at 2:57 PM | Comments (5) | TrackBack

August 2, 2006

engagement in the Middle East, without government

We can expect a big debate between 2006 and 2008 about whether America should disengage from the Middle East or continue to intervene there. Disengagement would require cutting our use of foreign oil, reducing our military aid to Middle Eastern states, and avoiding both military and diplomatic entanglements. Continued intervention would mean some more thoughtful and effective combination of diplomacy and occasional military force.

If you'll excuse the cliché, there is a Third Way. We could engage in the Middle East, but not through the federal government. We have deep experience now with informal diplomacy, with cultural exchanges through universities and other independent institutions, and with transnational social movements that can promote democracy without working through the state.

I think the fiasco of the current intervention in Iraq cannot be fully blamed on the Bush administration. It is a more systemic failure, and blame must be shared (in some proportion that I do not know) by the uniformed military, the press, the political opposition, and even American citizens in their relationship to politics. There are some general lessons here about the susceptibility of large bureaucratic institutions to massive failure, especially when they have vast resources and power and monopolize information. The argument for non-governmental politics seems stronger than ever.

[August 3: Coincidentally, the same topic is now under discussion at Crooked Timber.]

Posted by peterlevine at 4:41 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

August 1, 2006

index construction

For a client, CIRCLE is preparing an index of American civic engagement that will aggregate the trends in more than 40 indicators over the past thirty years. Our various trends begin and end at different times, depending on the whims of survey designers and changes in actual behavior. Therefore, it wouldn't work to build an index by averaging the indicators for each year. If an activity that happens to be common (such as wearing a political button or sticker) is suddenly included in the available surveys, then the whole index would jump up arbitrarily. Likewise, we couldn't add measures of new and relatively rare forms of engagement, such as writing blogs, without arbitrarily lowering the index.

Therefore, I'm proposing that we measure the percentage-point change in each indicator compared to the baseline year in which it was introduced. For instance, watching the TV news enters the National Election Survey in 1984 at 72% and rises to 85% in 1986. I don't include it at all in 1984, but count it as 13 points in 1986. The index is thus a weighted average difference in all the indicators compared to when they began. Adding blogging doesn't lower the index, but as blogging becomes more popular, the growth tends to raise the index.

I don't know if this is an original method--probably not. I also don't know for sure if it's a good idea. I think it has some advantages, especially for measuring a category (such as "civic engagement") that is likely to evolve over time.

Posted by peterlevine at 4:16 PM | Comments (3) | TrackBack