« June 2006 | Main | August 2006 »

July 31, 2006

the Gospels on two hot-button issues

On Saturday, Laurie Goodstein wrote a story in the New York Times about a Minnesota megachurch pastor, Rev. Gregory A. Boyd, who has broken with the conservative movement. He is not the only evangelical in revolt against the GOP, and the political implications are interesting. But I was struck by something different in the article: a point of theology and biblical interpretation. According to Goodstein's paraphrase, Rev. Boyd said that "Christians these days [are] constantly outraged about sex and perceived violations of their rights to display their faith in public. 'Those are the two buttons to push if you want to get Christians to act,' he said. 'And those are the two buttons Jesus never pushed.'"

Indeed, I cannot think of an episode in which Jesus demands the right to display his faith in a public setting, nor a moment when he expresses outrage about sexual behavior. In fact, there are two Gospel passages in which he does quite the opposite.

Chapter 12 of Mark ends with Jesus teaching in the Temple (a public edifice devoted to religious ceremony). Four brief episodes within that chapter praise privacy or discreetness in matters of faith. First, some Pharisees ask Jesus whether it is permissable to pay taxes using a coin that bears a graven image of Caesar Augustus, who is portrayed blasphemously as a god. Jesus replies that a public expression contrary to his belief is of no consequence; what matters is his inward faith. "Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar's, and to God the things that are God's."

Next, a scribe "discreetly" accepts Jesus' interpretation of Moses' Law. The scribe confesses to Jesus that the whole Law means this: "to love [God] with all the heart, and with all the understanding, and with all the soul, and with all the strength, and to love his neighbour as himself, is more than all whole burnt offerings and sacrifices." The scribe's discretion--as well as his rejection of public ceremony--seems to please Jesus.

Then Jesus inveighs against those who make a show of their faith:

Beware of the scribes, which love to go in long clothing, and love salutations in the marketplaces, and the chief seats in the synagogues, and the uppermost rooms at feasts: which devour widows' houses, and for a pretence make long prayers: these shall receive greater damnation.

And finally he singles out a woman who, I have always imagined, makes her modest contribution very discreetly, out of shame for her poverty:

And Jesus sat over against the treasury, and beheld how the people cast money into the treasury: and many that were rich cast in much. And there came a certain poor widow, and she threw in two mites, which make a farthing. And he called unto him his disciples, and saith unto them, Verily I say unto you, That this poor widow hath cast more in, than all they which have cast into the treasury: For all they did cast in of their abundance; but she of her want did cast in all that she had, even all her living."

While Mark 12 is about public displays of faith (and therefore relevant to debates about prayer in school), the great text for understanding Jesus' view of sexuality is John 8:2-11, the story of the "Woman Taken in Adultery." It's a rich and controversial text, and I have pasted my own interpretation below the fold. (This comes from my book-in-progress about Dante.)

According to Deuteronomy, every case of adultery involves a married woman or a betrothed virgin who "lies with" a man. There are two possible places where this can take place: within the city or in the fields. In the city, the woman has a duty to cry out if she is raped, so if she is found with a man, her consent is assumed and she merits execution by stoning. Outside the city, however, no one can hear her cries, so she is considered innocent. In all cases, the man with whom she "lies" is to be stoned to death. These clearly defined categories are supposed to cover all instances (Deut. 22:22 27).

Jesus' enemies presumably thought that he disliked some aspects of the strict Old Testament law. They tried to entrap him by asking his opinion of an adultery case:

2. And early in the morning, he came again into the temple, and all the people came unto him; and he sat down, and taught them.3. And the scribes and Pharisees brought unto him a woman taken in adultery; and when they had set her in the midst,

4. They say [sic] unto him, Master, this woman was taken in adultery, in the very act.

5. Now Moses in the law commanded us, that such should be stoned: but what sayest thou?

6. This they said, tempting him, that they might have to accuse him. But Jesus stooped down, and with his finger wrote [or drew] on the ground.

7. So when they continued asking him, he lifted himself up, and said unto them, He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her.

8. And again he stooped down, and wrote [not drew] on the ground.

9. And they which heard it, being convicted by their own conscience, went out one by one, beginning at the eldest, even unto the last: and Jesus was left alone, and the woman standing in the midst.

10. When Jesus had lifted up himself, and saw none but the woman, he said unto her, Woman, where are those thine accusers? Hath no man condemned thee?

11. She said, No man, Lord. And Jesus said unto her, Neither do I condemn thee: go, and sin no more (John, 8:2 11).

This passage could be read as evidence of Jesus' "antinomianism:" his hostility to outward, written, or formal laws, and his embrace of emotions such as love and pity. Nietzsche, for one, thought that Jesus was a thorough antinomian who was misunderstood by the whole mainstream Christian tradition. According to Nietzsche, "Jesus said to his Jews: 'The law was for servants—love God as I love him, as his son! What do morals matter to us sons of God!'"

To anyone who views laws and ethical doctrines as burdensome, this permissive interpretation of Jesus' teaching will be appealing. But such readers will have difficulty explaining his admonition: "Think not that I am come to destroy the law ... For verily I say unto you, Till heaven and earth pass, one jot or one tittle shall in no ways pass from the law, till all be fulfilled. Whosoever therefore shall break one of these commandments, and shall teach men so, he shall be called the least in the kingdom of heaven" (Matt. 5:17 19).

A second reading makes Jesus sound more judgmental and demanding even than Moses. According to this interpretation, Jesus internalizes the Mosaic Law, assessing intentions rather than actions. This is perhaps how he "fulfills" the Hebrew law of adultery. "Ye have heard that it was said by them of old time, Thou shall not commit adultery: But I say unto you, That whosoever looketh on a woman to lust after her hath committed adultery with her already in his heart" (Matt. 5: 27 28). On this definition, the scribes and Pharisees are evidently as guilty as the woman whom they found in "the very act"; and they have no business judging her. Nevertheless, Jesus subscribes to a clear definition of adultery, and the woman is guilty if (but only if) she felt lust in her heart. If Jesus’ main purpose was to internalize the Law, then he would have been in agreement with some mainstream rabbis of the same era, who taught that "evil thoughts are worse than lustful deeds," and that the worst form of adultery was to imagine another man while actually having sex with one's husband.

On the other hand, if Jesus condemns all who feel lust in their hearts, then why does he forgive the Woman? He does not claim that her adultery was involuntary. Being free of sin, he could cast the first stone against her.

A third interpretation is at least as plausible. Tony Tanner writes: "The scribes and Pharisees ... set up a situation in which the woman is brought forward as a classified object to be looked at and talked about; they have depersonalized her (a woman taken in adultery) and reified her (she is 'set' in their midst). Christ refuses to look and, initially, refuses to talk. That is, he refuses to participate in this specular attitude to the woman and to discuss her as a category. By doing this he restores the full existential reality to the situation."

The "full existential reality" is captured in the Gospel narrative. Even if we have read the story many times before, it can still generate suspense. A woman has been snatched from some intimate setting by a mob intent on stoning her to death. (It is worth imagining exactly how this would feel.) She is hauled into the temple to be used as a test for a radical young rabbi. She clearly belongs within the class of "adulterers" as defined by Deuteronomy. How then can Jesus rescue her without violating Holy Scripture? After an anxious pause, he succeeds by forcing the concrete reality of the situation onto the consciousness of the scribes and Pharisees. They must stop applying rules in order to consider individuals—themselves first of all. As Tanner writes, Jesus' question "thrusts them back into their own interiority (they are 'convicted by their own conscience'), and it dissolves the group identity within which they have concealed themselves (they go out 'one by one' as individuals, having arrived as ‘scribes’ and Pharisees')."

It would be fascinating to know what Jesus wrote while the audience awaited his verdict. But we pointedly are not told, which leaves us to interpret a bare act of writing. This reminds us that we are reading a written text, whose purpose is to relate the concrete facts of Jesus' life in order to provoke a moral and spiritual transformation in the reader. "These are written, that ye might believe that Jesus is the Christ, the son of God, and that believing ye might have life through his name" (20:31). Perhaps Jesus' purpose is similar: he also wants to inscribe a story so that appropriate moral judgments will follow. His story encompasses one woman’s actions, intentions, feelings, and circumstances, which Jesus knows because he can read her perfectly. "He knew all men, and needed not that any should testify of man: for he knew what was in man" (2:24-25). He is the ideal interpreter and narrator—hence, the ideal judge.

Seamus Heaney reads this story as an illustration of writing's moral value. "Faced with the brutality of the historical onslaught," he writes, poetry and the other imaginative arts "are practically useless. Yet they verify our singularity, they strike and stake out the ore of self which is at the basis of every individuated life." Poetry, Heaney asserts, is just like Jesus' writing on the ground:

It does not say to the accusing crowd or the helpless accused, ‘Now a solution will take place,’ it does not propose to be instrumental or effective. Instead, in the rift between what is going to happen and whatever we would wish to happen, poetry holds attention for a space, functions not as distraction but as pure concentration, a focus where our power to concentrate is concentrated back on ourselves.This is what gives poetry its governing power. At its greatest moments it would attempt, in Yeats’s phrase, to hold in a single thought reality and justice.

When Jesus is asked to judge the Woman Taken in Adultery, we expect him to offer an "instrumental or effective" solution: an answer that will acquit her (if that's what she deserves), without violating the Law. In other words, we expect a clear and valid doctrine. But Jesus, by his mysterious act of writing, pointedly refuses such a solution. Instead, his writing somehow combines reality and justice.

Yeats had in mind poetry's capacity to describe an ideal alternative to mundane reality. So for example, he regarded the “circuits” in his metaphysical system "as stylistic arrangements of experience comparable to the cubes in the drawing of Wyndham Lewis and to the ovoids in the sculpture of Brancusi. They have helped me to hold in a single thought reality and justice." Along these lines, Jesus' writing (or drawing?) could be understood as a mystical and transcendent act, something that challenges his audience to rise above standard human behavior.

An alternative appeals to me more. On this view, Jesus combines reality and justice by describing the concrete details of the Woman’s life, using words that are appropriate to the facts but that also have strong moral connotations. He knows, perhaps, that she has fallen in love, that she has gained self-respect, that she has suffered coercion, that she has experienced tender pleasure, that she regrets her infidelity, and other such details. By acknowledging them, he challenges the crowd of scribes and Pharisees to think in a similarly concrete and judgmental way about themselves as well as about the Woman. The thinking that he requires of them resembles the detailed, perceptive descriptions that are typical of fiction and poetry. Without resort to mysticism or paradox, these descriptions hold reality and justice in a single thought.

As Rev. Boyd knows, Jesus never demands the right to express personal faith in public settings, nor does he condemn people for breaking rules about sexuality. He saves his ire for religious show-offs and sexual puritans. Boyd's fundamentalist faith has led him to reject some major points of the conservative political agenda. (He also rejects idolotry of the flag and militarism). This is not only politically auspicious--it's interesting.

Sources

Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, 164

C.G. Montefiore and H. Loewe, A Rabbinic Anthology (London, 1938), § 745 (Yoma 29a, init); §748 (Tanhuma [ed. Buber], Naso §13 f. 16a).

Tony Tanner, Adultery in the Novel: Contract and Transgression (Baltimore, 1979) pp. 22 23.

Seamus Heaney, "The Government of the Tongue," in The Government of the Tongue: Selected Prose, 1978 1987 (New York, 1988) pp. 107 8.

Yeats, A Vision (New York, 1966), p. 35.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:39 AM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

July 28, 2006

is volunteering an elite activity?

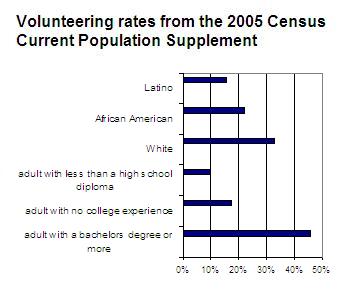

The Census data on volunteering show that there are big gaps by race/ethnicity and especially by educational background. Almost half of college graduates say they volunteer, compared to less than one in ten adults who dropped out of high school. I didn't attempt any statistical analysis, but it appears that educational background is the important factor. African Americans might volunteer at higher rates than Whites if you controlled for educational background.

Volunteering has advantages for those who do it: it educates and connects people to their fellow human beings. That's one reason to be concerned about the gap in volunteering. We might also worry that, if most volunteers are well-off and White, there will be inadequate volunteer services in disadvantaged communities. And privileged volunteers may misunderstand or patronize those they serve.

If we are concerned about this gap, we could try to close it by providing more service opportunities and support (including perhaps financial support) for less advantaged Americans.

On the other hand, there is a class-bias inherent in the concept of "volunteering." If a person with a paid day-job helps other people's kids at the local school, that's volunteering. However, if a stay-at-home Mom carefully monitors the neighborhood kids, she is unlikely to describe herself as a volunteer. And if a person chooses to work as a public school teacher, she isn't a "volunteer" unless she also helps after-hours at a soup kitchen or cleaning up a park.

Thus it's possible that it's not actual volunteering that's mal-distributed, but only the way we define it.

Posted by peterlevine at 4:26 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

July 27, 2006

blogging in Africa

Joshua Goldstein is a young American who lives and works in Uganda. He has written a very interesting essay for his blog about new media in Africa. He argues that blogging, in particular, can help build respectful, human relationships between the developed world and the Global South. (In the interests of full disclosure, Josh is a former Maryland undergraduate--but not a student of mine.)

Posted by peterlevine at 4:47 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

July 26, 2006

the link between civic engagement and culture

Here's an argument, inspired by Tocqueville, that we can assess the health of a democracy by examining the heterogeneousness of its culture.

Truly engaged citizens produce diverse cultural products. That is because cultural identity is always contested; it provokes debates, parodies, and expressions of dissent as well as consensus. Besides, engaged people clump together in communities and associations, each of which inevitably takes on a distinct character. Many communities and associations choose to display their identities through music, statuary, graphic design, narrative history, and other forms of culture.

Conversely, a homogeneous, mass culture is a threat to civic engagement, because when only a few people produce products that reach a mass market, they obtain great influence. Today, various groups of Americans criticize mass culture for being secular, materialistic, superficial, violent, sexist, and racist, and for undermining local, traditional, and minority cultures. These critiques are not always mutually consistent and may not all be valid. But it seems clear that people feel powerless to change mass culture; that feeling demonstrates the tension between mass culture and democracy.

Mass culture is, in part, a product of corporate capitalism. Capital investment increases the audiences for certain books, films, and songs. Sometimes corporate power is relatively weak: for instance, when there is competition among many producers (as in the Jacksonian era of small printers or in today's age of blogs), or when the government sponsors cultural production (as in Western Europe). However, there remains an intrinsic tendency for liberal and democratic societies to develop mass cultures.

When people are free to choose which cultural products to consume, a small handful of products become enormously more popular than the rest. It is not certain why this occurs, but it seems plausible that people want to know what other people are reading, hearing, or viewing; thus they gravitate to what is already popular, making it more so. That instinct is perhaps especially strong in a democracy, where people are taught to believe that average or majority opinion is a reliable guide to quality. Books are advertised as "best sellers," movies as "blockbusters," and songs as "hits" because democratic audiences trust popularity. In aristocratic cultures, on the other hand, elites have disproportionate consumer power and tend to view popularity as a mark of poor quality. Aristocrats want to have unusual tastes. As Tocqueville wrote:

Among aristocratic nations every man is pretty nearly stationary in his own sphere, but men are astonishingly unlike each other; their passions, their notions, and their tastes are essentially different: nothing changes, but everything differs. In democracies, on the contrary, all men are alike and do things pretty nearly alike. It is true that they are subject to great and frequent vicissitudes, but as the same events of good or averse fortune are continually recurring, only the name of the actors is changed, the piece is always the same. The aspect of American society is animated because men and things are always changing, but it is monotonous because all these changes are alike.

Tocqueville thought that mass culture posed a serious threat to liberty. But he proposed a solution. Strong voluntary associations would have the means and the incentive to produce differentiated alternatives to mass culture.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:06 AM | Comments (3) | TrackBack

July 25, 2006

a light unto the nations (II)

As a follow-up to yesterday, I want to emphasize that Israel may defend itself. However, as a democracy, it needs national unity and the authentic support of fair-minded outsiders. Both will come only if Israel has a reputation for actively seeking a just peace.

Today, Prime Minister Olmert's office said that "Israel has no intention of harming the Lebanese population and that Israel is fighting against the Hezbollah terrorist organization and not against the Lebanese government or its citizens. ... The prime minister said he was very sensitive to the humanitarian situation in Lebanon."

This is something you have to show and not just say. In fact, treating Lebanese refugees as simply a "humanitarian" problem threatens to reduce their self-respect. Given Israel's overwhelming conventional military superiority, it should take pains to:

show explicit and deep respect for Arab and Moslem civilizations;

forcefully maintain a commitment to respecting Arab lives;

express solidarity with the democracy of Lebanon, even while complaining about its unwillingness to confront Hezbollah;

explain that Israel's goal is to coexist in peace with strong, prosperous, independent neighbors;

refrain from undermining the dignity and self-respect of Arab populations, even during wars; and

take all reasonable measures to spare non-combatants.

The last precept would be more difficult to follow if killing civilians in aerial attacks were Israel's most effective means of self-defense against Hezbollah's rockets. However, I doubt very much that that is the case.

[Update: See Gideon Levy's "Days of Darkness" in Haaretz: "Israel is sinking into a strident, nationalistic atmosphere and darkness is beginning to cover everything. The brakes we still had are eroding, the insensitivity and blindness that characterized Israeli society in recent years is intensifying. ..."]

Posted by peterlevine at 4:49 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

July 24, 2006

a light unto the nations

Richard Cohen's Washington Post piece last week began, "The greatest mistake Israel could make at the moment is to forget that Israel itself is a mistake. It is an honest mistake, a well-intentioned mistake, a mistake for which no one is culpable, but the idea of creating a nation of European Jews in an area of Arab Muslims (and some Christians) has produced a century of warfare and terrorism of the sort we are seeing now."

As you would expect, this opening sparked some fire in the blogosphere. In fact, it was the most blogged-about statement of the day, described variously as "poison," "projectile vomiting," the "asinine quote of the century," and a "bizarre attack on Israel," written by a "self-hating terror enabler," a "Jew who can be relied upon to provide cover for ... malignant pyschosis and racism." (I quote from half a dozen different blogs.)

Cohen could have argued against the current Israeli military action without calling the country a "mistake." I doubt that the debate he launched will be productive. It would be more timely to discuss whether the bombing and ground invasion of Lebanon comport with just war theory. We should also debate whether these actions can possibly advance the interests of Israel, rightly understood. As the Israeli Meretz Party is asking, Is there an exit strategy? Is there a plausible scenario in which the invasion leads to peace and security?

However, over the longer term, the question of Israel's legitimacy is unavoidable. The Jewish state is a democracy that needs the voluntary and enthusiastic support of its own people and the authentic friendship of at least some foreign countries. Therefore, it is not wrong to raise the question of whether Israel is a "mistake"--and if not, why not.

Some complain that Israel is singled out for criticism, even though the neighboring tyrannies receive less scrutiny. But the governments of Syria, Jordan, and Egypt have no legitimate moral claims; they merely have guns. Men enlist in the Syrian army because they are drafted. Subjects obey the Syrian state because otherwise they will be tortured. Other countries deal with Syria because they have no alternative.

A democratic state is a different kind of project. It asserts a right to govern on the basis of justice. It is therefore an appropriate question whether the State of Israel state is just, whereas there is no need to ask that question in relation to Syria or even Jordan and Egypt.

Israel was created by a vote of the United Nations, and its citizens still want to be a nation. Even if the original Zionist project was a mistake, the state of Israel has a presumptive right to exist, just as the USA is legitimate regardless of the merits of Manifest Destiny. America was built on land stolen from the indigenous population so that it could be worked, in significant measure, by imported slaves. We nevertheless have a legitimate--indeed, an excellent--polity that rests today on the consent of the governed. Israel's foundation was, at the least, less bloody that our own. Like any democracy, Israel must show that its current behavior and laws are just; its origins are history.

Thus, as a friend of Israel, I worry about the defenses of that nation that I read on English-language blogs in response to Cohen's post. I don't know how much of the Israeli population these blogs represent, but I have also encountered the same views in offline conversations. The main arguments are: (1) God gave Israel to the Jews in perpetuity; (2) Jews lived in what is now Israel for many centuries of antiquity; and (3) There were hardly any Arabs in Palestine before the Jewish immigration of the late 1800s.

I cannot accept the premise that Israel is God's gift, nor should the United States or the global community. Unlike the argument that Israel deserves respect because its constitution is just, an appeal to scripture can move no one except fundamentalists. The premise that Jews are the original occupants of Israel is of dubious relevance. Similar logic would imply that those of European ancestry who live today in North and South America, Australia, and South Africa must go back "home" and leave those lands to the native populations. As for the argument that Palestine was "deserted swampland" between 68 CE and 1870--this raises a host of problems.

First, I doubt it's true. It is hard to tell from the World Wide Web how many Moslem and Christian Arabs really lived in what would become British Palestine in 1890 or 1910. This is an intensely touchy subject, and many people have created responsible-looking websites that provide radically different estimates. Yehoshua Porath's estimate of more than 200,000 sounds well-argued to me; it appeared in a respectable publication; and it's perfectly consistent with contemporaneous descriptions of Ottoman Palestine quoted on the Zionist websites, which make the area seem relatively lightly populated but far from "deserted."

I am not learned about Middle Eastern history and cannot settle the debate about how many Arabs lived in Palestine before the big Jewish immigration. But it does seem risky to tie one's national self-respect to a claim that there weren't many of another people present on your land before your countrymen arrived. Mrs. Netanhayu once told Queen Noor of Jordan, "When the Jews came to this area, there were no Arabs here. They came to find work when we built cities. There was nothing here before that." What if that turned out to be false? Given her rationale for the Zionist project, must Mrs. Netanyahu reject the state of Israel if someone shows her that there were Arabs in Palestine in 1880?

Not only bloggers, but people I have known offline denigrate the old Arab population of Palestine, claiming that the few resident Arabs were pathetically poor and illiterate until the Jews arrived. This is an empirical claim that could, for the little I know, turn out to be true. But it's morally dangerous to want to believe that another group was so bereft and despondent that their defeat at your hands was a blessing for them. That is a deeply condescending assumption that can easily become habitual.

The Jewish state needs a proper sense of self-respect and a national project that it can confidently defend. It still has a chance, I believe, to embody an inspiring story that unites and motivates its own people and impresses fair-minded outsiders. Its national narrative can still be about an oppressed but peace-loving people who have built a decent society in the face of adversity. But that self-image depends upon just behavior. To be the light unto nations, Israel must be law-abiding, moral, democratic, and a force for peace. Then when someone questions (or seems to question) the nation's legitimacy, Israelis can reply by emphasizing its goodness.

It seems to me that in the first thirty years of the Jewish state's existence, it was more sinned against than sinning, and its accomplishments were remarkable. But once Israel became an occupying power with a substantial and restive subject population of Moslems and Christians, the national narrative became untenable. At that point, claims that the country was a "mistake" really started to sting. Some defenders took refuge in caustic arguments about the inferiority of "the Arabs." Those claims would, at best, provide a poor foundation for national unity. Because it is a democracy committed to the rule of law, Israel must be just if it hopes to survive at all.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:01 AM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

July 16, 2006

on the road

I'm flying to Los Angeles today and staying for most of the week. Because I expect my Internet access to be sporadic, I'm planning not to blog until July 24. That's probably a good thing, anyway. By the end of August, I owe a book manuscript about youth and the future of democracy. If I can spend a week without the distractions of email and blogging, I think I can get close to finishing the book. Besides, it's hard to think about any topic of public importance right now other than the conflagration that seems to have engulfed most of the region from Mumbai to Gaza. On that topic, I have no insight, no expertise, no special knowledge--nothing but the Aristotelian response to tragedy: pity and fear.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:50 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

July 14, 2006

what will happen to youth turnout in '06?

This is a question that we're being asked with increasing frequency at CIRCLE. [One person who has asked is Zachary Goldfarb, who published a good story on the topic in the Sunday Washington Post.]

Clearly, youth turnout will be lower than it was in 2004, a presidential election year during which participation of the whole population returned to a level last seen in 1968. Youth contributed more than their share to that increase, but will surely vote at a lower rate in the upcoming congressional elections. After all, many live in completely uncompetitive House districts in states with no Senate races. Thus the relevant comparison is not to 2004 but to the last congressional election (2002) or the last election that followed a big surge in youth turnout (1994).

The comparison to 1994 is interesting because that election was viewed as a test of us Gen-Xers. My generation had turned out in the Bush-Clinton-Perot race of 1992. Would we respond to the call of celebrities like Madonna (who, wrapped only in an American flag, told us, "If you don't vote, you’re going to get a spankie”), or would we prove to be slackers? We were slackers, voting at a 22% rate in the momentous election that gave Republicans control of the House. For the Millennials, 2004 was a banner year like 1992; and 2006, like 1994, will be viewed as something of a test.

What will happen next November depends on why there was a big surge in 2004. The reasons may include:

1. Generational replacement. The Millennials are different from X-ers in some basic and attractive ways; for example, they are more engaged in their communities, more optimistic, and more trustful of major institutions (other than the press). These qualities might explain higher turnout in '04 and would help again in '06.

2. Mobilization: Anecdotal evidence suggests that the parties and interest groups invested a lot of money in 2004 in techniques that work for young voters (such as face-to-face canvassing). They also specifically targeted youth. The level of mobilization will be lower this year, but probably at least as high as it was in 2002. An additional piece of good news is that mobilization in one election still motivates people in the next--as shown by careful experimental studies.

Partisanship: Although young voters skew toward moderates and independents and are still forming their political identities, they are increasingly hostile to the incumbent party. That anger was a motivator in 2004 and might again turn out the youth vote in '06. However, Republican youth may not turn out unless the GOP works to mobilize them. The net result if Republicans stay home will be a bad year for youth turnout.

Attentiveness: Following the news is a leading indicator, because you must know what's going on before you can vote. Young people's news consumption rose sharply after 9/11/01. I see no evidence that it has increased since 2002. In fact, I would guess that it has fallen off.

Posted by peterlevine at 1:56 PM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

July 13, 2006

international law and the current mideast conflict

I think that Hamas, Hezbollah, and Israel are all in violation of the Fourth Geneva Convention, Art. 33-34: "No protected person may be punished for an offence he or she has not personally committed. Collective penalties and likewise all measures of intimidation or of terrorism are prohibited. ... Reprisals against protected persons and their property are prohibited. ... The taking of hostages is prohibited."

Hamas and Hezbollah took hostages, not just prisoners, if they captured soldiers for the purpose of exchanging them for Israeli prisoners. But Israel admits that its response is a form of collective punishment. For instance, "Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert held Lebanon directly responsible for the ambush and promised a 'painful and far-reaching response.'" The pain, evidently, is to be suffered by the Lebanese collectively, not just by Hezbollah as a military organization.

The Fourth Geneva Convention clearly binds Israel and Lebanon, which are signatories. When the PLO was responsible for the occupied territories, it filed a letter expressing a desire to sign as well. (The Swiss Federal Council replied "that it was not in a position to decide whether the letter constituted an instrument of accession, 'due to the uncertainty within the international community as to the existence or non-existence of a State of Palestine.'") In 1977, some countries--including the US but not Israel--accepted an addendum that would even more clearly render illegal some of the recent actions taken by Israel. I think the addendum is morally appropriate, although one could debate whether Hamas fits the description in Article 1 of "peoples fighting against colonial domination and alien occupation and against racist regimes in the exercise of their right of self-determination".

The text of the addendum is below the fold. [I see that Chris Bertram on Crooked Timber has a similar take.]

Article 1

This Protocol, which supplements the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949 for the protection of war victims, shall apply in the situations referred to in Article 2 common to those Conventions.

... The situations referred to in the preceding paragraph include armed conflicts which peoples are fighting against colonial domination and alien occupation and against racist regimes in the exercise of their right of self-determination, as enshrined in the Charter of the United Nations and the Declaration on Principles of International Law concerning Friendly Relations and Co-operation among States in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations. ...

Article 85

In addition to the grave breaches defined in Article 11, the following acts shall be regarded as grave breaches of this Protocol, when committed wilfully, in violation of the relevant provisions of this Protocol, and causing death or serious injury to body or health:

(a) making the civilian population or individual civilians the object of attack;

(b) launching an indiscriminate attack affecting the civilian population or civilian objects in the knowledge that such attack will cause excessive loss of life, injury to civilians or damage to civilian objects, as defined in Article 57, paragraph 2 (a)(iii);

(c) launching an attack against works or installations containing dangerous forces in the knowledge that such attack will cause excessive loss of life, injury to civilians or damage to civilian objects, as defined in Article 57, paragraph 2 (a)(iii);

(d) making non-defended localities and demilitarized zones the object of attack;

(e) making a person the object of attack in the knowledge that he is hors de combat ...

Posted by peterlevine at 3:54 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

July 12, 2006

box score political reporting

One of the standard clichés of journalism is the treatment of political news as if it were a sport. Each event is described as a victory or a defeat for a particular politician. For instance, here's how the two papers that I read over breakfast this morning reported the latest Administration policy on prisoners:

The New York Times: The new policy "reverses a position the White House had held since shortly after the Sept. 11 attacks, and it represents a victory for those within the administration who argued that the United States' refusal to extend Geneva protections to Qaeda prisoners was harming the country's standing abroad."

The Washington Post: "The developments underscored how the administration has been forced to retreat from its long-standing position."

The Administration's change of position was a defeat: that's a fact. And it's undeniable (almost tautological) that the shift was a "victory" for those who opposed the status quo. But reporters could choose many other facts to provide: for example, information about what has been done to various prisoners. The reliance on political wins and losses has the following serious drawbacks:

1) It encourages laziness. You don't have to do any actual reporting to figure out that an event is good or bad for a politician.

2) It reinforces the notion that politics is a spectator sport, in which the important question is "Who's winning?" (not, "What's happening?").

3) It adds to the political cost that incumbents incur when they change course for good reasons. When George Bush found out that Abu Zubaydah, whom he had described as Al-Qaeda's chief of operations, was mentally ill and of no consequence, he supposedly told CIA Director George Tenet, "I said he was important. You're not going to let me lose face on this, are you?" If that's true, it's evidence of almost criminal irresponsibility. But Bush also knew that if he changed his position, the press would report that as a sign of weakness--a "setback" or "defeat"--instead of allowing the president to take credit for learning. Reporting politics as a box-score only increases the odds that leaders will act like Bush.

(In fairness, I should note that after I read this morning's papers and decided to write this post, I looked around for other examples of box-score journalism on the prisoner issue. The AP, Reuters, and L.A. Times stories really did not use that frame.)

Posted by peterlevine at 8:00 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

July 11, 2006

democratic skills for professionals

What does an aspiring urban public school teacher need to know? Before she starts teaching, she should learn the material she is supposed to cover, something about pedagogy and assessment, some instructional techniques--and the ability to address fundamental problems in the system in which she will work. She cannot solve educational problems inside her own classroom, because senior managers and big bureaucratic structures create too many hurdles. She cannot take on managers and bureaucracies alone. In my experience, unions are unreliable. Thus she needs to work with other teachers, parents, kids, and community-members, often quite different from herself, to address common problems together.

Democratic skills (listening, deliberating, organizing, petitioning) are essential for teachers, as they are for many other professionals. For a good teacher, "civic engagement" is not a voluntary after-work activity, but the heart of her professional life. Therefore, it is exciting to watch Minneapolis Community College's Urban Teacher Program embrace "advocacy and activism." Specifically, their Associate's Degree students lead urban students in Public Achievement projects. In Public Achievement, kids choose, define, and address community issues--a genuinely open-ended, non-ideological form of politics that will serve teachers well.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:53 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

July 10, 2006

the press and civic engagement

Below the fold, I have pasted a longish draft essay on the evolution of the news media and its impact on democracy. (A revised version will go into a book on civic engagement that is due next month.) In essence, I argue that we had a particular model of the news business between 1900 and 2000 that became increasingly dysfunctional for citizens. It offered limited opportunities to write the news--that's a well-known flaw. It also assumed an audience of people who were interested in public issues and who trusted professional reporters to be objective, balanced, reliable, and independent. That audience encompassed the most active citizens, as surveys show. But it shrank rapidly in the last quarter of the 1900s. Resurrecting the twentieth-century press now seems impossible, but the new digital media have promise.

Until the Progressive Era (ca. 1900-1914), most American newspapers and magazines reflected the positions of a party, church, or association and aimed to persuade readers or motivate the persuaded. The exceptions, beginning with the New York Sun in 1833, were independent businesses that sought mass audiences in big cities. All 19th-century newspapers freely combined opinion and news. They printed fiction and poetry along with factual reporting. They often ran whole speeches by favored politicians or clergymen. Standards of evidence were generally low. However, publications were relatively cheap to launch, so they proliferated; 2,226 daily newspapers were in business in 1899.[1] A small voluntary association or independent entrepreneur could break into the news business, hoping to make money or to push a particular ideology, or both.

The nineteenth century was also an age of partisan citizenship, in which people were expected to show loyalty to a party, a union, a church, a town or state, and sometimes a race or ethnic group. Often such loyalties were ascribed from birth; they were matters of affiliation rather than assent, as Michael Schudson writes.[2] Voting was a public act, an expression of loyalty, not a private choice. Politics involved torchlight parades and popular songs; the essence of civic life was boosterism; and newspapers were written in a similarly rousing, communitarian spirit.

As Schudson has shown, the new model citizen of the Progressive Era--an independent, well-informed, judicious decision-maker--needed a different kind of newspaper, one that provided reliable information clearly distinguished from opinion, exhortation, and fiction. Leading newspapers were separated from parties and religious denominations and began to claim objectivity and independence. Their intended audience became all good citizens, not just members of particular groups. When they introduced opinion columns and letters pages, they often strove for ideological balance. As Adolph Ochs announced when he bought The New York Times in 1896, his intention was to “give the news, all the news, in concise and attractive form, in language that is parliamentary in good society, and give it early, if not earlier, than it can be learned through any other reliable medium; to give the news impartially, without fear or favor, regardless of any party, sect, or interest involved; to make of the columns of The New York Times a forum for the consideration of all questions of public importance, and to that end to invite intelligent discussion from all shades of opinion.”[3]

The transformation of the American press coincided with the ascendance of logical positivism, which sharply distinguished verifiable facts from subjective opinions.[4] Furthermore, the independent newspaper arose along with the modern research university, whose mission was to create independent, judicious decision-makers instead of loyal members of a community. Finally, the new press reflected an ideal of a trained, professional journalist that took shape when many other occupations were also striving to professionalize.[5]

At about the time when journalists developed ideals of objectivity, independence, and neutrality, the news business consolidated. For example, the number of daily newspapers in New York City fell from 20 in the late 1800s to eight in 1940. Meanwhile, the first newspaper chains were established.[6] Most people began to obtain news from a daily publication with a mass circulation, and they had relatively little choice. Consolidation of the news business and journalistic professionalism could be justified together with one theory. An excellent newspaper--and later, an excellent evening news show on television--was supposed to provide all the objective facts that a citizen needed in order to make up his or her own mind. The citizen did not need much choice among sources, because any truly professional and independent news organ would provide the same array of facts. Some competition might be valuable to encourage efficiency and rigor, but all credible journals would compete for the same stories. Choice was a private matter to be exercised after one had read the newspaper or watched TV. One was to be guided not by an ascribed identity but by making informed selections among policy options.

This new model had idealistic defenders, but it also had several serious drawbacks that became increasingly clear as the century progressed. First, the new journalism was probably not as effective at mobilizing citizens as the old partisan press had been. Although we lack data on individuals’ newspaper use and civic engagement from before the 1950s, we know that overall turnout and other measures of participation fell as the press consolidated and aimed at professionalism. It seems likely that the new journalism was less motivating.

Second, it became harder to break into the news business once newspapers needed not only printing presses, ink, and paper, but also credentialed journalists, editors and fact-checkers, and a staff large enough to provide comprehensive coverage (“all the news that’s fit to print”). Thus the telling of news became the province of a few professionals employed by large businesses, not an activity open to many citizens. That problem worsened once radio and television arrived.

Third, journalistic professionalism often seemed to introduce its own biases. For example, journalists were trained not to editorialize in news stories. That meant that they often simply quoted other people’s controversial views, usually aiming for as much balance as possible between voices on either side of a debate. To call the president a liar is to editorialize; to quote someone who holds that view is to report a fact. But one still has to choose whom to quote, and the tendency is to interview famous, powerful, or credentialed sources--often those with talents or budgets for public relations and axes to grind. In 1999, 78 percent of respondents to a national survey agreed: “powerful people can get stories into the paper--or keep them out.”[7] Sometimes the norm of “balance” created a bias in favor of the mainstream left and mainstream right, marginalizing other views. On occasion, it meant that reporters gave excessive space to demonstrably false opinions, because they saw their job as reporting what prominent people said, not what was right.

While professional reporters felt bound not to promote policy positions, those who closely covered campaigns and administrations believed they could say who was winning and losing and why politicians had adopted their current positions. Similarities between candidates’ views and public opinion (as measured by the newspaper’s own polls) were taken as evidence that politicians were simply trying to attract votes. Thus readers were offered a relentlessly cynical view of politicians’ motives, plus an interminable policy debate among experts who were equally balanced between the right and left, plus polls showing that one side or the other was bound to win. It is no wonder that many lost interest in politics. None of this coverage helped citizens to play a role of their own.

Modern professional journalism placed a tremendous emphasis on politics as a “horse race.” Three quarters of broadcast news stories during the 2000 campaign were devoted to tactics and polls; only one quarter, to issues.[8] As CNN political director Mark Hannon explained in 1996, his network conducted daily polls because they “happen to be the most authoritative way to answer the most basic question about the election, which is who is going to win.”[9] In fact, during a campaign, the most basic question for a citizen is not who will win, but which candidate to support. But reporters reflexively see that question as one for the editorial pages, whereas they can cover polls as simple empirical facts. Yet the depiction of politics as a horse race suggests that a campaign is a spectator sport (and not a particularly elegant or entertaining one). Controlled experiments have found that such coverage raises cynicism and lowers engagement.[10]

Finally, the ideal news organ of the Progressive Era demanded a lot of trust from its readers. Perhaps objectivity, independence, and balance are possible in theory; in practice, however, any news source is a fallible human product. Major newspapers, magazines, and broadcast news have powerful effects on politics and public opinion. The newspaper that claims to be objective, independent, and nonpartisan asks us to believe that the consequences of its reporting are involuntary, caused by the facts and not by any political agenda. That defense can be hard to swallow. In 2004, two thirds of all Americans thought they detected at least a “fair amount” of bias.[11]

The most glorious chapter in the history of the modern American press was written between 1965 and 1975, when The Washington Post and The New York Times published the Pentagon Papers, broke the Watergate scandal, and had their constitutional role as independent watchdogs upheld by the Supreme Court. Their reporting certainly had consequences, helping to end a war and bring down a president. That was all very well if one opposed the Vietnam War and President Nixon. But the same power could also be used against President Clinton or against the welfare state. Anyone whose political goals were frustrated by the press might find it difficult to trust reporters as objective and independent. One’s skepticism might be reinforced by the fact that each newspaper has owners, investors, and advertisers with economic interests. Writers and editors, too, form a definable interest group.

The debate about corporate power in the news media is at least a century old and is perennially important. In the 1990s, a new discussion began that concerned reporters’ professional norms. Some reporters, editors, and academics argued that the newsroom ideals developed during the Progressive Era no longer served democracy and civic engagement. A newspaper like The New York Times, as Ochs had envisioned it, presumed a public that was interested in current events and ready to act on the information it read. But that public was shrinking, and it could be argued that the prevailing style of news reporting was actually making it smaller by increasing cynicism. Adversarial, “watchdog” journalists still played an important role in periodically uncovering scandals, but it was not clear why an individual citizen should spend money and time reading such information every day. When a big scandal broke, the opposition party or law enforcement was supposed to address it. Why should individuals pay for independent oversight as a public good? Only those who were already civically engaged would choose to subscribe to the watchdog press. Their numbers were falling, and they could find ever less information in the newspaper that could inform for their own civic activities.

In the 1990s, under the labels of “public journalism” or “civic journalism,” news organs experimented with new forms of reporting that might better serve active citizens and enhance civic engagement. For example, instead of reporting the 1992 North Carolina Senate campaign as a horse race (with frequent polls and numerous articles about the candidates’ strategies), the Charlotte Observer convened a representative group of citizens to deliberate about issues of their choice and to write questions for the major contenders. The newspaper offered to publish the questions and responses verbatim. Meanwhile, its beat reporters were assigned to provide factual reporting on each of the topics that the citizens chose to explore. When Senator Jesse Helms refused to complete the questionnaire that the citizens had written, the Observer published blank spaces under his name.[12]

Careful evaluations have found positive effects from this and other such experiments. But public journalism faltered as a movement by the end of the decade.[13] One of the reasons was the sudden rise of the Internet. The newspaper business, panicked by independent websites and bloggers, lost interest in civic experimentation. Meanwhile, many of proponents of public journalism began to see the Internet as more promising than reforms within conventional newsrooms.

After all, blogs, podcasts, and other digital media make possible a return to the press that existed before the Progressive Era--for better and, for worse. The barriers to publication have fallen, not only because websites are cheaper than printing presses, but also because a mass audience has returned to products created by individuals and amateurs. Blogs are endlessly various. Some are specialized sites devoted to careful, factual reporting on particular topics, but most are motivational, ideological, and opinionated, with comparatively low standards of evidence and no trained reporters, fact-checkers, or editors. However, there are millions of them and they often check one another’s facts. Young people are heavily represented and have better opportunities to enter the fray than at any time since 1900.

Twentieth century news media claimed to separate fact from fiction--not always successfully. Then the audience for straight news reporting shrank, along with the rate of civic engagement. But fiction can promote civic participation, as long as it is of high quality. For example, it appears that watching and discussing the fictional world of The West Wing (an NBC television drama) has positive civic effects, whereas watching sitcoms is bad for civic engagement.[14] Unfortunately, the balance of material that major entertainment businesses provide is not good for democracy. But barriers to making films have fallen: artists and other citizens have growing opportunities to create and promote work in all genres that helps people to engage.

Blogs, short videos and audios, and other innovative news media should help to many people to mobilize and organize their fellow citizens. Until recently, trust in journalists, consumption of newspapers, and civic engagement were strongly correlated, but the links may be weakened if people can gain the information they need to participate from other sources. Those who are not inclined to trust the mainstream press will still be able to participate.

Clearly, there are also dangers. An online audience can screen out uncomfortable ideas, thereby splitting into ideologically homogeneous “echo chambers.” There is a relative scarcity of online content devoted to local communities. It can be difficult to distinguish the source and reliability of online information. And the web provides a sometimes confusing mix of fact, opinion, error, deliberate falsification, and overt fiction.

Each of these dangers can be addressed by citizens working online, and sometimes software can help. For example, Wikipedia provides surprisingly reliable information through a system of peer review involving many thousands of volunteers. Technorati’s software increases the chance that bloggers will engage in conversations with their critics, by alerting them whenever their writing has been linked from elsewhere. Social networking software like MySpace (which is currently very popular among the young) can be tweaked so that it helps people identify neighbors with similar political interests.

If there is hope that citizens can address the drawbacks of the new online media through voluntary action, then it would be unwise to enact policies to shape what should be a free space. We should, however, act to prevent two pressing problems. First, it is possible to make handsome profits by limiting customers’ access to material produced by ordinary citizens and driving them to corporate content. Internet service providers may be tempted to provide quicker access to websites that pay them for that advantage; cable companies may charge higher fees for uploading data than for downloading corporate material; and most search engines already sell preferential treatment. Legislation is needed to keep the Internet neutral and open.[15]

Second the “blogosphere” still depends on daily news journalism. Therefore, cuts in newsroom staff and attempts to replace hard news with entertainment are still damaging, even in the Internet era.

NOTES

1. Bruce M. Owen, Economics and Freedom of Expression: Media Structure and the First Amendment (Cambridge, MA, 1975), table 2A-1.

2. Michael Schudson, The Good Citizen: A History of American Civic Life (New York: The Free Press, 1998), p. 6.

3. Quoted by Schudson, p. 178, who notes that Ochs also pledged to promote “right-doing” and to maintain a commitment to political principles, such as “sound money and tariff reform.” But it was the section I quote that was most influential,

4. An influential defense in English was A.J. Ayer’s 1936 book Language, Truth, and Logic. However, the prestige of logical positivism owed more to the apparently unambiguous progress of science before World War II than to any theoretical defense.

5. Burton J. Bledstein, The Culture of Professionalism: the Middle Class and the Development of Higher Education in America (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., l976); Schudson, pp. 179-182.

6. Mitchell Stephens, “Newspaper,” Collier’s Encyclopedia, 1994, available via www.nyu.edu/classes/stephens.

7. American Association of Newspaper Editors, “Examining Our Credibility,” August 4, 1999, available via www.asne.org/kiosk/reports/99reports.

8. Annenberg Public Policy Center, “Networks Only Aired About One Minute of Candidate-Centered Discourse a Night in the Days Leading to the Election: More Stories Focused on Horse-Race & Strategy

than Issues & Substance,” press release, Dec. 20, 2000.

9. James Bennet, “Polling Provoking Debate in News Media on its Use,” The New York Times, Oct. 4, 1996, p. A24.

10. Joseph N. Cappella and Kathleen Hall Jamieson. Spiral of Cynicism: The Press and the Public Good. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997)

11. Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, “Cable and Internet Loom Large in Fragmented Political News Universe: Perceptions of Partisan Bias Seen as Growing, Especially by Democrats,” January 11, 2004.

12. Peter Levine, The New Progressive Era (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2000), pp. 156-7

13. Lewis A. Friedland, Public Journalism: Past and Future (Dayton, Ohio: Kettering Foundation Press, 2003 {P???}

14. Dhavan V. Shah, Jack M. Mcleod, and So-Hyang Yoon, “Communication, Context, and Community An Exploration of Print, Broadcast, and Internet Influences,” Communication Research, Vol. 28, No. 4, 464-506 (2001)

15. Jeffrey Chester, “The Death Of The Internet : How Industry Intends To Kill The 'Net As We Know It,” TomPaine.com, October 24, 2002.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:30 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

July 7, 2006

youth media and the audience problem (revisited)

I'm interviewing adults who help youth to make digital media (videos, podcasts, online newspapers)--and also some of the kids who actually do this work--to find out what kinds of audiences they want to reach and how satisfied they are with their impact. (Some background here.) Yesterday, I interviewed the leader of an important nonprofit that trains kids to make documentaries. She said that youth in her program are encouraged to think about their audience from the beginning of their projects. At first, they want to reach "everyone," but then they "fine-tune" their goals to be more realistic and to enhance their impact on their communities. They are less concerned, she said, with the number of viewers than with "the kind of conversations" that they provoke.

The youth in this program are "very eager to get an audience" and to provoke "public discussions," because showing their work makes it "real"; it provides "evidence to the kids themselves" that they have achieved something significant.

Left to their own devices, adult audiences usually ask unhelpful questions, such as: "Why did you choose this topic?" Or "Do you want to be a professional film-maker?" The youth have begun to circulate better questions in advance, such as: "What can we do about the problem that you have presented in your video?" Or, "What were the strongest and weakest parts of the documentary?" Adults like to be guided in this way.

Most of this discussion and feedback occurs in face-to-face settings. A good example was a public screening of a youth-made video about gentrification, attended by academic experts, activists, and some of the kids' parents and friends. The discussion was very rich and rewarding for the young film-makers. Overall, my interviewee thought that youth were both satisfied and dissatisfied with their audience--glad for the feedback they receive, but not fully satisfied by their impact on their communities.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:42 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

July 6, 2006

logical positivism and chivalry

Until yesterday, I did not know the following story about the major British philosopher A.J. Ayer, which wikipedia borrows from Ben Rogers' life of Ayer. In 1987, "At a party ... held by fashion designer Fernando Sanchez, Ayer, then 77, confronted Mike Tyson harassing Naomi Campbell. When Ayer demanded that Tyson stop, the boxer said: "Do you know who the **** I am? I'm the heavyweight champion of the world," to which Ayer replied: 'And I am the former Wykeham Professor of Logic. We are both pre-eminent in our field. I suggest that we talk about this like rational men.' Ayer and Tyson then began to talk, while Naomi Campbell slipped out."

Posted by peterlevine at 1:28 PM | Comments (3) | TrackBack

July 5, 2006

newspapers and civic engagement

Almost two centuries ago, Tocqueville detected a close relationship between journalism and civic engagement. Newspapers were the main news organs of his day, and he wrote that "hardly any democratic association can do without" them. "There is a necessary connection between public associations and newspapers: newspapers make associations and associations make newspapers; and if it has been correctly advanced that associations will increase in number as the conditions of men become more equal, it is not less certain that the number of newspapers increases in proportion to that of associations. Thus it is in America that we find at the same time the greatest number of associations and of newspapers."

I wanted to see whether the relationship that Tocqueville observed impressionistically remains true. Yesterday, using the 2000 American National Election Study, I found strong, statistically significant relationships between people's frequency of reading a newspaper, on one hand, and their likelihood of volunteering, working on a community issue, attending a community meeting, contacting public officials, belonging to organizations, and belonging to organizations that influence the schools (but not protesting or belonging to an organization that influences the government). To illustrate these relationships with an example: 42.4 percent of daily newspaper readers belonged to at least one association, compared to 19.4 percent of people who read no issues of a newspaper in a typical week.

I did not control for other factors, such as education. Nevertheless, it appears that residents who engage in their communities also seek information from a high-quality source--and vice-versa. Having information about current events gives one relevant facts and motives to participate; and participation leads one to seek information.

Rates of newspaper reading have fallen sharply. I realize there is nothing sacrosanct about the printed daily newspaper; websites or radio and television broadcasts could, in theory, be just as good for civic engagement. But there is no evidence that the electronic media have yet compensated for the decline in newspaper consumption.

Posted by peterlevine at 4:20 PM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

July 4, 2006

"the objectivist v. the constructivist"

A couple of professors have a joint blog in which they debate political issues from their opposing positions (respectively, libertarian and progressive). The tone tends to be "hot," but the authors evidently enjoy the exchange and keep it going after the first volleys. Each post begins with a pair of essays that were first published in local newspapers, the Dunkirk-Fredonia (NY) Observer and the Jamestown (NY) Post-Journal. A nice example is their debate over school vouchers. I was put off by the initial ad hominem characterization of people who oppose vounchers. (That's my position, at least for now, yet I don't think I'm beholden to teachers' unions, ignorant of the facts, or hate kids.) However, both sides ultimately score some good points.

Posted by peterlevine at 1:27 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

July 2, 2006

more on spinning Hamdan

The scramble that I predicted last Friday--to fix the meaning of Hamdan--has begun. The Post's headline on Saturday read, "GOP Seeks Advantage In Ruling On Trials: National Security Is Likely Rallying Cry, Leaders Indicate." Just as I suspected, there have been efforts to link the Supreme Court's ruling against Bush to the New York Times' decision to publish national security leaks. "It will be worse for the Democrats to be seen as favoring the terrorists than favoring the New York Times," says one talk-show host.

The administration will want the following to be the popular interpretation of Hamdan: Five justices of the Supreme Court (a bunch of lawyers) found various technical grounds (including treaties negotiated by foreigners) to make life more difficult for the military. Congress now has a duty to support the Commander in Chief by creating military tribunals by statute. In the future, presidents will have to cross their t's and dot their i's in cases very similar to Hamdan. But in cases with significant factual differences from Hamdan, they can go ahead and act unilaterally again, and the Court ought to rule for the executive.

That reading of the case would be very bad for majoritarian democracy, the rule of law, and limited government--values of special concern to principled conservatives. (See, for instance, Patriots to Restore Checks and Balances). Just as true conservatives should want to restore the balance of powers, so partisan Republicans should see the importance of reimposing checks on the executive branch--otherwise, a Democratic president may use federal agencies to suppress rights that they value.

In my opinion, it's a rhetorical mistake for Members of Congress to emphasize their own prerogatives, as Senator Spector did by saying that from now on decisions will be made by Congress, "because it's our constitutional responsibility." That sounds like a matter of turf--and Congress is none too popular. I'd rather hear that the Court required us, the American people, to make difficult decisions about how the United States shall handle captives in the current struggle. Such decisions cannot be made by presidential fiat but must be debated openly, because they are our responsibility. Because Congress has the formal power to pass legislation, we must follow the Congressional debate, deliberate, express our views, and vote accordingly in November. That, after all, was how the framers intended us to govern ourselves.

Posted by peterlevine at 2:10 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack