« August 2005 | Main | October 2005 »

September 30, 2005

ideology and the professoriate

I'm in New Brunswick, NJ, for the Imagining America national conference. I'll speak tomorrow. My assigned theme is "difficult dialogues." The other panelists will discuss a large, Ford-funded initiative by that name that seeks to "promote pluralism and academic freedom on campus."

When I think about "difficult dialogues" in relation to the arts and humanities, the dialogue that strikes me as the most difficult and most necessary of all is a conversation between academics--who tend to be liberal or radical--and the 62 million Americans who voted for George W. Bush last November. I plan to argue that:

1. Academics are overwhelmingly liberal, especially in the arts and humanities. (I'll cite some data to this effect.)

2. The gulf in attitudes between academics and the median US voters is causing tangible problems for intellectual culture and academia.

3. We can take some constructive steps to improve the situation.

I've covered several of those points on this blog before. However, I haven't previously considered the following explanation for the gulf in attitudes between academics and median American voters. In global perspective, it is the US electorate, not the American professoriate, that is out of the mainstream. American professors are cosmopolitan, and thus share more with foreign peers and colleagues than with the ideological outliers back home.

Indeed, on a one-dimensional ideological scale from left to right, the median American voter is quite far to the right compared to the world's population, and the median American academic is closer to the global middle. But this one-dimensional scale conceals all kinds of complexities. There are ways in which American voters-—populist, anti-authoritarian, libertarian, multiculturalist, and rights-oriented—-can be more "radical" than Europeans. There are certainly homegrown traditions of radicalism that are concealed if one applies the international definition of the "left."

Besides, even if it's true that American academics are centrists in the global dialogue and outliers only in our own country, that's still a problem. Our country is where we live, earn our salaries, find our students, and—-in many cases—-hold citizenship. The gap may not be out fault, but it is our problem, because no one else is going to solve it for us.

I believe that a solution lies in an idea that Harry Boyte is developing. Boyte wants us to see ourselves as "culture makers" in a democratic society. Many Americans consider mass culture to be coarse, commercial, celebrity-driven, and violent. It's very slick and doesn't provide openings for ordinary people to create anything for a public audience. Culture also feels dangerously uncontrollable. You can't shield yourself or your children from the vulgar aspects of mass culture without also insulating yourself from the news and public life. Hollywood and the music industry occasionally respond to targeted protest campaigns, but they don't seem in general to care about people's thoughtful and deliberative opinions about quality.

Democratic action through the state probably can't make much difference. The First Amendment rightly protects media companies, even if they create coarse and violent material. But there is great potential for partnerships between lay citizens and professional "culture-makers" who want to create alternatives that are more responsible, ethical, and serious. Academics, along with clergypeople, entertainers, journalists, and other professionals in the knowledge and communications business, can exercise powerful leverage.

I don't imagine that there is consensus about what's wrong with pop culture. For some people, it's the pervasive anti-gay prejudice; for others, it's the increasingly tolerant representation of homosexuality. But we don't need consensus; we just need more chances to reason together about what culture should mean and to create things--not in one big, homogeneous group, but in diverse and sometimes overlapping communities. Universities should be at the heart of this work.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:01 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

September 29, 2005

the trial of William Penn

I was looking for a quote (which I didn't actually find), and I ended up reading an entire account of William Penn's trial in 1670. I believe the account--available with modernized English spelling on a University of Texas website--was written by Penn himself, so it is not unbiased. In fact, I find it somewhat hard to imagine that the wicked judge would actually mutter to himself, "Till now I never understood the Reason of the Policy and Prudence of the Spaniards, in suffering the Inquisition among them: And certainly it will never be well with us, till something like unto the Spanish Inquisition be in England." Nevertheless, the story makes gripping theater and has contemporary resonance. (I recommend skimming until p. 4, where the action really starts.)

For background: Penn (a Quaker) had been preaching in violation of the Conventicle Act, which forbade "all meetings of more than five persons beyond a household, if any, for worship other than that prescribed by the Liturgy." The Sheriff of London and other authorities were afraid to charge Penn under the Act, lest it be overturned. Instead, they arrested him and William Mead on undisclosed charges. The two Friends were subjected to Newgate Prison's "Bale-dock, and Nasty-hole, nay, the menace of a Gag, and Iron Shackles too." They were brought before a Middlesex (London) jury. The trial itself shed no light on whether the defendants had broken any law, but it did (according Penn's account) involve such entertaining exchanges as the following:

Clark: Bring William Penn and William Mead to the Bar.

Mayor: Sirrah, who bid you put off their Hats? Put on their Hats again.

Observer [Penn himself]: Whereupon one of the Officers putting the Prisoners Hats upon their Heads (pursuant to the Order of the Court) brought them to the Bar.

Recorder: Do you know where you are?

Penn: Yes.

Recorder: Do not you know it is the King's Court?

Penn: I know it to be a Court, and I suppose it to be the King's Court.

Recorder: Do you not know there is Respect due to the Court?

Penn: Yes.

Record: Why do you not pay it then?

Penn: I do so.

Record. Why do you not pull off your Hat then?

Pen: Because I do not believe that to be any Respect.

Record: Well, the Court sets forty Marks a piece upon your Heads, as a Fine for your Contempt of the Court.

Penn: I desire it might be observed, that we came into the Court with our Hats off (that is, taken off) and if they have been put on since, it was by Order from the Bench; and therefore not we, but the Bench should be fined.

The judge demands that the jury find Penn guilty, although without stating the charges. Penn makes a stirring defense of the jurors' rights as Englishmen. I won't spoil the suspense by relating the conclusion, in case you don't happen to know what happened. The official US Court system website provides a summary of the whole event that concludes--rather surprisingly--with a positive account of jury nullification.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:19 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

September 28, 2005

9/11 and civic participation, revisited

In a recent post, I took issue with an op-ed that Tom Sander and Robert Putnam had written in the Washington Post. I thought they were arguing that 9/11 had caused young people's values to change, and as a result young adults had become more involved in civic life, broadly defined. I suspect, in contrast, that what matters is the opportunity and the invitation to participate, not one's values. Thus 9/11 wouldn't matter unless it caused adults to create more civic opportunities for youth. I cannot prove this thesis, and in fact I am currently seeking money for a longitudinal study to test it. In any case, Tom Sander has replied to my blog, noting correctly that I had misread aspects of his original op-ed. He and Putnam did not claim that 9/11 changed values, leading to more volunteering. Instead, they believe that 9/11 helped to increase interest in politics and discussion of current events--which I find quite plausible. Sander and Putnam have adopted a subtle position for which there is some evidence (although I wonder why youth turnout declined slightly in 2002, if interest in politics was up). Anyway, I don't want to confuse the major question--"Values or opportunities?"--by misrepresenting anyone's views.

Incidentally, the following article is relevant:

Edward Metz and James Youniss, "September 11 and Service: A Longitudinal Study of High School Students' Views and Responses" Applied Developmental Science, 2003, Vol. 7, No. 3, Pages 148-155. This is a "study of a suburban public high school near Boston. ... Results from our pre-post measures revealed only an immediate increase in students' political interest and no changes in intended civic participation. Descriptive findings showed that most students' view of the world was changed after 9/11. Yet, fewer students reported that their view of themselves had changed. ... Statistical analyses showed that students who organized service had enhanced and sustained levels of intended civic participation compared to students who responded through other means or not at all."

Posted by peterlevine at 11:40 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

September 27, 2005

making room for God without "intelligent design"

Here's a proposal for how to think about evolution if you want to believe in divine providence: Even if science explains the "efficient causes" of evolution, God can be the "final cause."

Aristotle argued that "Why?" can generally be answered in four ways simultaneously. The efficient cause is a preceding event that reliably generates the result, as my finger hitting the keyboard causes a letter to appear on the screen. The material cause is a characteristic of the object involved. For instance, my computer is so structured that it produces letters when touched in a certain way. (Perhaps a better example: I am communicating right now because it is in the nature of the substance known as "mind" to think and to express its thoughts.) The formal cause relates to the essence or definition of the object. For instance, my computer generates letters because that's what computers do; that's its "form". And the final cause concerns goals and purposes. I type these letters in order to communicate certain ideas to you.

Modern science began when Francis Bacon argued that experiments could (only) reveal efficient causes. Since Bacon, scientists have considered Aristotle's material and formal causes to be simplifications of efficient causes. If you want to know how a computer works, you really need to understand a chain of predictable events. To say that a computer is an object that generates text (an example of a formal cause) is not to explain it.

As for final causes, they are not detectable by science. According to Bacon, natural events don't happen for a purpose; they happen because something else happened first and led regularly to the result. Without Darwin, we would assume that there were final causes in the biological world, for organisms seem to move and evolve toward goals. But biology since Darwin has been free of final causes (it has become "non-teleological"). For example, biologists do not really believe that genes are "selfish" and "want" to propagate. Rather, genes mutate as a result of prior chemical processes, and the mutations that help organisms survive tend to proliferate. It is unnecessary to cite purpose. Higher organisms have wills and goals, but those arise because of prior, physical causes.

Stripping the natural world of purpose upsets religious believers. In fact, I can understand that a non-teleological universe is profoundly disturbing; nothing has a purpose. Thus some believers are moved either to deny that evolution has occurred at all, or to claim that an "intelligent designer" is the efficient cause of evolutionary change.

The latter is a dangerous strategy--on theological grounds. Efficient causes should be detectable by experiments. To hypothesize an efficient cause is to make an empirically testable claim. In theory, an experiment might reveal the existence of a hidden intelligence--or it might not. Or (in principle) it might detect an intelligence that is fairly powerful and fairly wise--but that would not be the Judeo-Christian/Islamic god, who is all-powerful. Real omnipotence cannot be detected, because all that one can ever see is a finite quantum of power. I am reminded of the controlled experiments that (supposedly) find a statistically significant effect from prayer. To claim that invoking God has an effect of a few percentage points strikes me as almost blasphemous. Is this the God of glory who thundereth, who breaketh the cedars of Lebanon?

Besides, any efficient cause is itself an effect. If we were to discover an Intelligent Designer who plays with genes to achieve certain ends through evolution, then we should be able to explain what caused that designer to exist. But God has no efficient cause.

Thus I think orthodox monotheists should choose a different course. They should accept Bacon's idea that efficient causes are detectable by experiments. But God should not be subjected to such tests; that would not be compatible with faith or with the concept of omnipotence. Still, efficient causes can co-exist with final causes. Perhaps homo sapiens evolved because of a random genetic mutation in a primate ancestor (that would be the efficient cause of our species). At the same time, people could have evolved in order that God would have the opportunity to sacrifice His only-begotten son. The latter claim would be untestable, but it would follow logically from faith and revelation.

People who accept this recommendation (which has surely been made before), cannot find a justification for teaching "intelligent design" in science classes. However, they can be confident that no experiment will ever threaten their faith or reduce divine power to something observable and (therefore) finite.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:36 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

September 26, 2005

the difficulty of changing educational policy

I should be optimistic about the prospects for better civic education--and (more generally) the potential for civic renewal in America. Within the last 10 days, I’ve had a chance to testify before the new American Bar Association Commission on Civic Education, which is co-chaired by Sandra Day O’Connor and Bill Bradley and includes other distinguished leaders. I’ve attended the National Council on Citizenship’s annual conference, with hundreds of participants. Next was an advisory board for America's Promise, an organization with considerable clout that wants all adolescents to have, among other things, opportunities to serve in their communities. And today I’m participating in the third annual Congressional Conference on Civic Education, which convenes delegations from all 50 states. At the Congressional Conference, Justice Stephen Breyer, Howard Baker, Lee Hamilton, Tom Foley, Margaret Spellings, and other luminaries have addressed the plenary group with enthusiasm.

Yet I don’t think I’ve ever been so aware of the barriers to change. We know (more or less) what students should experience in schools to prepare them for democracy. They should take classes that introduce them to great principles and issues of democracy and that help them to see how these themes relate to their own practical concerns. Students should be able to serve in their communities and write about or discuss their service. There should be youth groups that they can join, including student governments and school newspapers. They should have opportunities to discuss current issues with neutral and well-informed adults as moderators. They should get a hearing when they express their views on the governance of their own schools. And they should occasionally play challenging civic roles in simulations such as Model UN, mock trial, or computer games about politics.

We know much less about how to change policies so that kids have better odds of experiencing good civic education. To influence education, legislatures and other powerful institutions can create or enact mandates for courses; mandatory assessments (either with our without high stakes for students); educational mandates and/or support for teachers; rules promoting freedom of speech and assembly and free, meaningful participation within schools; changes in the certification of education schools; and even changes in the fundamental structure of schools, for example to make them smaller, more diverse, or more thematically coherent. Lawmakers can also repeal excessive mandates in other subjects that compete with civics. They can provide additional funding, especially for extracurricular activities; or purchase particular textbooks and other teaching materials.

These decisions are made by school administrators, school systems, state agencies, the federal government, and independent associations such as accrediting organizations. Many thousands of policymakers have a say; often some groups play others to stalemate. The division of responsibility is one reason that successive waves of educational reform have left actual practices (both pedagogy and curriculum) remarkably unchanged over 50 or even 80 years. Of all areas of education, civics is particularly hard to shift, since very few policymakers are concerned about civic outcomes.

We are trying to create a movement in favor of the necessary reforms. The movement now has some traction, as shown by the prominent and dedicated people who have come aboard. But the effort would be much easier if we could formulate a short list of priorities that would apply everywhere. For example, it would make life easier if we could say that every student should have a service-learning class, or that every school should have a school newspaper. These proposals are brief enough to fit on a bumper-sticker and easy enough to be widely repeated.

However, in educational policy, one must respect federalism and local control. Matters really are different in each community; one set of reforms would not help everywhere. Besides, education is a fiercely guarded state prerogative, and states resist national mandates. Even No Child Left Behind, one of the boldest federal interventions in the history of US education, leaves it to the states to set most standards. This is one reason that we cannot recommend a single policy prescription for everyone.

Furthermore, it isn't responsible to promote bumper-sticker-size slogans. So much depends on the quality of a particular approach and the degree to which teachers and students genuinely embrace it. A service-learning mandate would probably result in a great deal of low-quality programming, as indeed is the case in Maryland, where every student is required to conduct service for graduation, and most of what they do is meaningless. A mandatory civics course would make little difference, since most students who reach 12th grade already have to take such a course. Requiring two courses instead of one would backfire if the courses were poorly taught or if they replaced an equally valuable class.

Finally, we lack information about state- or system-level policies that make a difference in civics. There is a database (which my organization, CIRCLE, co-funded) of state civic-education policies. This database shows that some states require student to take several civics courses, to participate in service activities, or to pass a civics test. But no one has yet uncovered evidence that any existing combination of policies works better than any other.

For a while this year, I hoped that we might have an opening when major school systems try to create much smaller high schools, as is being done in New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles. If it turned out that small schools produce better citizens (all else being equal), then we could join forces with the proponents of small schools and have a real impact. It was partly with that goal in mind that I organized a National Press Club event on small schools. However, I soon found that there is mixed and fragmentary research on smaller schools and civic outcomes. We don’t have the basis, in good conscience, to sign onto the small-schools movement without reservations and qualifications.

Conceivably, reading education provides another opening. Today, elementary reading curricula include almost nothing but fiction. Reading about history and social issues might prepare young children better for the existing, high-stakes reading exams while also giving them more civic knowledge and skills. However, we know too little at present about the long-term benefits of acquiring civic knowledge at a young age.

In the absence of a simple policy proposal, our de facto strategy is to build a robust network of people in favor of civic education (broadly defined), so that there are individuals who care about civics in every state. They can then decide what policy changes are most important in their local circumstances. They can jump on opportunities to create good programs--or play defense when someone threatens to remove civics or social studies or cut funding for youth groups. In the Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools, we like to advertise these and other successes of our state teams over the last year:

I am proud of our community for achieving these steps. Yet the modesty of their hard-won achievements reflects the tremendous difficulty of effecting substantial change.

The only alternative strategy that I can imagine is somehow to provoke a debate between liberals and conservatives over citizenship, so that each side would promote a somewhat different set of policies. For instance, imagine if a major Republican candidate in ’08 called for all students to take a high-stakes factual exam on American history; and a major Democratic candidate demanded that every student have a high-quality experience in service-learning. Whoever won would probably find it impossible (or at least inadvisable) to enact an actual federal mandate. Nevertheless, the debate might have a beneficial effect at the state and local level.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:35 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

September 23, 2005

positive youth development

I went to Capitol Hill yesterday to hear a panel on America's Children: Key National Indicators of Well-Being 2005. This is a remarkable document, produced jointly by many federal agencies, that gives a detailed (if incomplete) picture of the state of children over the last 25 years.

In the audience and at a lunch event were several distinguished psychologists who have pioneered the field of positive youth development. They argue that we too often view adolescence as a period of great danger and difficulty. Thus we measure success as the absence of serious problems, such as criminality and violence, pregnancy, accidents, disease, and educational failure. The goal of parents and governments alike is to get our kids safely through to their twenties.

Adolescence is potentially a great time of life, when people can learn, socialize, expand their horizons, create, and serve others. But we tend not to measure the rate at which teenagers have such positive experiences, and we certainly don't organize public policy to maximize positive opportunities. Of course, advocates of positive youth development want to reduce the incidence of teenage crime, disease, and other bad things. But they argue that we will get better results if we put resources into supporting positive activities, rather than preventing and punishing misbehavior. Clearly, this idea has a political valence. Liberals often want to spend money on arts programs and service-learning, and conservatives want more police. Nevertheless, the evidence for positive youth development is not merely ideological and should stand on its own.

There is a parallel--often noted by practitioners in the two fields--between positive youth development and asset-based community development, about which I have written before.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:21 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

September 22, 2005

essential historical facts?

I believe that people should know some facts about politics, history, and law. You can't get along with skills alone; and not all facts are equally important. But how do we reason about what information is essential and what is trivial?

At an event earlier this week, I heard Eugene Hickock, a former US Deputy Secretary of Education, tell two stories that he intended to shock the audience. He had recently asked a family friend who is an excellent current college student to name the final battle of the Revolutionary War, and she couldn't come up with "Yorktown." (In the audience, all our jaws were supposed to drop when we heard this.) Also, Dr. Hickock now teaches constitutionalism in law school. Since the states are the issue in federalism, he asks his students to name all of the state capitals--and they cannot do it!

Now, I happen to think that a list of state capitals is mere trivia (you can look them up if you need them), although if an adult US citizen doesn't know about Sacramento, Austin, or Albany, that may reflect a lack of experience reading political news. I understand the significance of Yorktown and recognize that sacrifices were made there that have benefitted us ever since. And yet I would put the name of Yorktown far down on a list of important historical facts--far, far below the First Amendment, Franklin's diplomacy in France, the Stamp Tax, the existence of slavery in the colonies, and even the battles of Lexington and Concord.

I suspect that a room of reasonably open-minded people would soon agree about many items on a list of crucial facts and concepts, but some disagreements would persist. What criteria can we use to address such differences?

Posted by peterlevine at 8:35 AM | Comments (3) | TrackBack

September 21, 2005

New Orleans: civic innovation

The reconstruction of New Orleans represents an opportunity to employ techniques for civic participation that have been developed and tested over the last 30 years. For example:

There are excellent methods available for public deliberation. Over the next three months, people from New Orleans who have congregated in cities like Houston could be invited to forums run by AmericaSPEAKS. That's an organization that uses technology to mediate discussions among hundreds or thousands of people who gather in convention halls or other large venues. Meanwhile, dispersed citizens who have Internet access could deliberate online using a mechanism like that of e-thePeople. Finally, small clusters of people could use the Study Circles process to deliberate in living rooms, shelters, and church basements. All these discussions could be framed in the same way, and all the groups (large and small, offline and online) could report their results to a central agency.

I do not mean to suggest that the destruction of New Orleans is in any way a good thing, but we should try to rebuild as well as possible. I'm taking a cue here from E.J. Dionne's interview of Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-OR). Blumenauer sounds like my kind of person: an enthusiast for public participation, an environmentalist who's optimistic that we can make the lived environment better than it was before, a hawk about federal deficits, and a guy who's "always seeking to put together left-right coalitions on behalf of his eclectic mix of ideas." He told Dionne:

I've been in Congress for nearly 10 years and I've never been so optimistic that we have a chance not just to engage in the gargantuan task of helping people in the Gulf, but also of healing the body politic. ... You've got to build a citizen infrastructure along with all the roads and bridges. ... [P]eople should have a role in what it should be like, rather than have it done to them

I don't know if his optimism is justified, but we certainly need ideas, energy, and innovation.

Posted by peterlevine at 6:58 AM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

September 20, 2005

the importance of civics for less advantaged kids

Perhaps the main reason that I am so committed to the Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools is that civic education can increase the political clout of less-advantaged kids. Here is the evidence:

By advocating better civics education from k-12, we hope to benefit young people who are not on track for college, young people from poor households, and young people of color. The result should be more civic and political participation by those citizens.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:25 AM | Comments (4) | TrackBack

September 19, 2005

Miss Mary Bennet

A young lady of deep reflection am I.

I make extracts of homilies, pound my scales,

while Lizzy and Jane, hard at work, catch the eye

of gallant lads with lots of land. To such males

of fortune, we trade my sisters' pretty bodies.

My goods weren't good enough for my own cousin,

though I'd have picked him over those London dandies.

To me, living with just one idiot doesn't

sound so bad. He would never think to explore

what I keep inside books bound as Fordyce's Sermons

To Young Ladies, or, by Miss Hannah More,

Strictures on the Modern System of Young Women's

Education. Open those tomes from which I cite

my platitudes, and you'll find extracts, all right--

of Malthus, Blake, the Philosophy of Right.

I know just for what those wild Frenchmen fight.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:01 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

September 16, 2005

New Orleans: federal spending

In the aftermath of Katrina, an emerging line of argument goes like this: Bush is an anti-government conservative. Anti-government conservatives cut spending. Therefore, Bush cut spending. And the flooding has revealed the vulnerability of poor people when government spending is inadequate. I suspect that the real story is somewhat different. Bush is a profligate spender who borrows to finance rising expenditures. Cuts are coming, forced by the debt, but they have not happened yet. Therefore, it is generally inaccurate to attribute current social problems to Bush's spending cuts. The real culprits are decades, even centuries, of under-investment, plus very poorly managed government--both in big cities and, since 2000, at the federal level.

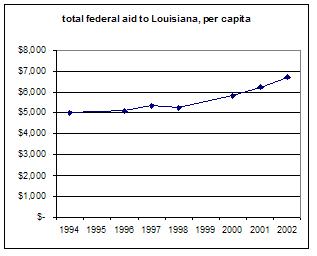

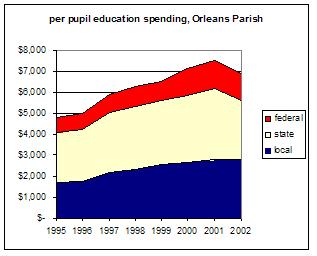

The full story is probably somewhat more complicated, since there have been federal cuts in some programs. I wish that financial data were more widely cited in the debate about what Katrina "means." In my limited discretionary time, I have created two graphs, both of which end in 2002. (More recent data are not easily found.)

The first shows that total federal spending per capita increased in Louisiana through 2002, although these numbers are not adjusted for inflation. Consistently, about 10% of the annual spending is for defense.

The second graph shows that spending per student in the Orleans Parish public schools rose, but then fell in the 2002-3 school year, mainly because of a drop in state support. Again, these figures are not adjusted for inflation.

I acknowledge that these are just snippets of information, and I'd welcome more detail about any actual Bush spending cuts that might have affected citizens of New Orleans.

Posted by peterlevine at 3:42 PM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

September 15, 2005

New Orleans: the youth/adult ratio and why it matters

According to the New York Times, in areas of New Orleans where there was significant flooding, the poverty rate was 29%, four out of five residents were people of color, and the ratio of adults to minors was (as I calculate it) 2.58-to-one. That is a similar ratio to what we see in Detroit and Camden, NJ. It is not too far below the national average of 2.5-to-one. But it is quite different from the pattern in wealthier neighborhoods. In contrast to the inner city, some of Detroit's suburbs have four adults per minor. Even the non-flooded parts of New Orleans (where the median income is much higher and about half of the residents are White) have an adult-to-minor ratio of 3.5-to-one.

Why does this matter? Dan Hart and colleagues argue that "child-saturated" communities--those with fewer than three adults per minor--do not provide many adult role models, much adult supervision, or many opportunities for participation in adult-led groups. On the bright side, when there are many youth, they can participate in volunteer activities together and benefit from positive peer role models. Youth are more likely to volunteer than adults; therefore, volunteering is particularly common in youth-heavy communities. But there is an important exception: youth-saturated neighborhoods that are also poor tend to have low levels of civic participation as well as high rates of delinquency. This is probably because young people suffer from the shortage of adult leaders, and there are too few youth organizations with adequate and legitimate funding to absorb most kids. The "autonomous youth culture" is subject to heavy influence by one group of local people who happen to have money and power: criminals.

Thus cities like Detroit and Camden face a shortage of adults along with their other problems. And I suspect that the low adult/youth ratio in New Orleans--which may have dropped further after the evacuation--is an important reason why order broke down there.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:48 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

September 14, 2005

they agree about one thing: Streetlaw

Since I'm on the board of Streetlaw, Inc., I can't resist quoting this snippet from the Roberts confirmation hearings:

ROBERTS: In addition to those actually involved in the case, one of the pro bono activities that I'm most committed to is a program sponsored by the Supreme Court Historical Society and an organization called Street Law. They bring high school teachers to D.C. every summer to teach them about the Supreme Court. And they can then go back and teach the court in their classes.And I've always found that very, very fulfilling.

HATCH: Well, thank you. My time is up.

Thanks, Mr. Chairman.

SPECTER: Thank you, Senator Hatch.

Senator Kennedy?

KENNEDY: Thank you, Mr. Chairman.

That Street Law program is a marvelous program. I commend you for your involvement in that.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:38 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

September 13, 2005

the effects of 9/11 on youth civic engagement

Over the weekend, both the New York Times and the Washington Post marked Sept. 11 with stories about a resurgence of civic engagement among American young people. The Post gave Harvard's Thomas Sander and Robert Putnam space to argue that "a renewed commitment to civic engagement among a crucial segment of the population"--young people--"has resulted from the "horrible event" of 9/11. For evidence, the authors relied on the latest HERI surveys of incoming college freshmen, which reveal big increases in volunteering, plus the turnout surge in the 2004 election. Meanwhile, the Times ran a news story by Alex Williams entitled "Realistic Idealists" that described some super-volunteers--like 13-year-old Hazel, who created a 3,000-volume library for a homeless shelter. Williams writes, "Hazel is at the leading edge of a generation whose sense of community involvement was born four years ago on Sept. 11, 2001. The attacks spurred an unprecedented outpouring of donations and volunteerism from Americans."

I never miss an opportunity to emphasize the idealism and civic creativity of today's young people. There are reasons, however, to doubt that 9/11 had a meaningful effect. At CIRCLE, we tend to explain the turnout increase as a result of feverish efforts to mobilize youth--although, to be sure, younger citizens were following current events more closely than usual in 2004, and one reason could be that 9/11 had caught their attention. Our own surveys found that adolescents were "all dressed up with nowhere to go" in 2002-4. That is, they expressed a heightened commitment to volunteering and other forms of participation, but they had no more than the usual opportunities.

Which brings me to the difference between Robert Putnam and Jim Youniss, some of whose views I mentioned here last week. For Putnam, values (such as trust, connectedness, and responsibility) underlie actions. For Youniss and colleagues, values tend to arise from participation, and what causes participation is (mainly) the opportunity to do something. If Youniss is right, then any effect of 9/11 on youth civic engagement would be indirect. Perhaps young leaders and adults responded to the attacks by creating venues for other young people to serve.

Another controversy is buried in the article by Sander and Putnam. Many people argue that 9/11 increased people's sense of connectedness (especially in New York City) but did little to enhance their capacity to solve public problems together. A national survey that CIRCLE released in 2002 found that many Americans of all ages volunteered, at least occasionally, but only 20 percent of the volunteers (and 10 percent of young volunteers) described their participation as a way to address a “social or political problem.” Putnam's own writing immediately after the 9/11 attacks was surprisingly apolitical; he seemed to be arguing that it would be good if people trusted one another more and cared more for others, but he said little about people's capacity for collective problem-solving. (I have written before about such apolitical notions of "social capital.)

Posted by peterlevine at 7:17 AM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

September 12, 2005

"expert" voices

I'm quoted in a recent story on Yahoo News (provided by Agence France Presse), entitled, "Katrina: US TV swings from deference to outrage towards government." The lead is, "In the emotional aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, US television's often deferential treatment of government officials has been replaced by fiercely combative interviews and scathing commentary." Some examples follow, and then I am quoted near the end:

Media expert* Peter Levine, of the School of Public Policy at the University of Maryland, said the shift in stance of American television was a return to normal following four years of toeing the government line following the September 11 attacks."After 9/11 those who publicly dissented from support of the president and the government were rounded on from all sides," he told AFP.

"The political calculation of (opposition) Democratic politicans was that it was best to support the president and so no one wanted to be seen dissenting, giving the media little to base any criticism on," he said.

But with local officials, including Louisiana Governor Kathleen Blanco and New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin openly slamming the government response to the New Orleans catastrophe, usually reserved media feel free to do the same, he said.

Added to that, the horror played out on live television belied the government's claims that its preparations for the storm and subsequent rescue effort had been sufficient.

"(Television stations) have people on the ground and are seeing a huge difference between what they are being told by officials and what they are actually seeing," Levine said.

None of this is profound or original, but it exemplifies the phenomenon I meant to describe. The reporter probably had the thoughts that he attributed to me before I said them. But he could not simply write those ideas down in his own words, because that would be editorializing, interpreting, or analyzing, and he couldn't do that as a reporter. His assignment was to record facts, such as what a "media expert" had said. So he called around until he found someone who told him something that he wanted to say himself, and then he quoted that person--in this case, me.

Between Sept. 11, 2001 and the Iraq invasion, relatively few of the people whom reporters quote were willing to say anything bad about US foreign policy, and that is why critical perspectives were so rare.

*My media "expertise" comes solely from regular reading of The New York Times, including the news, arts, op-ed, NY region, and business sections and the obituaries, but rarely the sports and never the new "style" section, which I condemn unequivocally.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:14 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

September 9, 2005

why it's important for young people to have civic opportunities

James Youniss and Daniel Hart have summarized more than a dozen longitudinal studies that follow young people into adulthood and repeatedly ask questions about their civic engagement and values. The basic pattern is very consistent: those who participate in politics or community affairs or leadership roles at age 15 or 22 are much more likely to be involved at age 30 or 50. Probably the longest study is by Kent Jennings, which finds a relationship between participation in high school groups in the 1960s and participation in community groups by the same people in the 1990s.

One possible explanation is that some people have a personality trait, moral value, or other internal characteristic that predisposes them to participate when they are young and still applies when they are older. In that case, it would not matter much whether adolescents and young adults were given opportunities to participate civically. Assuming they had the right mental predispositions, they would participate whenever they had an opportunity, even if they had to wait for adulthood. Our goal, in that case, should be to change hearts and minds, to make people feel civically responsible.

If this theory applied, then we might also understand certain historical events as the result of shifts in values: for example, the Civil Rights Movement would be a product of new consciousness among African Americans (and to a lesser extent, among Whites). By the same token, we should be concerned about certain negative trends in values, like the big increase in materialistic values held by incoming college freshmen since 1966.

However, the evidence tends to suggest a very different view. Based on surveys of participants and non-participants, it does not appear that young people engage in service or politics because they have particular values beforehand. It seems to matter much more whether they are recruited to participate, and whether they have appropriate skills and knowledge. But if values do not determine participation, participation does change values and habits. When we compare participants who appeared similar before a civic opportunity, we often find that they behave quite different afterwards. This was true of comparable people who did and did not participate in the Freedom Summer campaigns of 1964. Such profoundly moving and terrifying work might be expected to leave a lasting mark (see Doug McAdam's book, Freedom Summer). But the same is true to a lesser extent of young people who participate in student government or school newspapers. Even forty years later, they remain more civically engaged than other people who answered the same survey questions as they did.

To be sure, participants in civic life could have some disposition or character trait that was not measured in the surveys given before they chose to engage civically. That unobserved disposition could be responsible for their civic participation. But it is much more straightforward to assume that most people will participate if they are given the opportunity. The range in their characters and values doesn’t matter much; the opportunity is more important. Once people begin to participate, they obtain skills to engage civically; they get satisfaction from doing so; they enter networks that inform them about other opportunities and cause them to be frequently recruited; and their identity begins to shift. They begin to see themselves as citizens or participants, not as isolated individuals.

I was directly involved in conducting focus groups of some 75 highly engaged students at the University of Maryland in December 2004. They tended to tell a story of recruitment that led to habits of participation. Several acknowledged that they began to serve in high school because of pressure from parents or to improve their college prospects; but they found they liked it. “I became addicted to service,” one student said. Another observed, “You tend to see the same pattern, where people who were active in high school are the same people who come to college and are active.” Many students explained that they had become involved in a first campus group or program almost by accident, but then they were recruited to join other groups and activities. They suspected that if they had missed the initial invitation, they never would have become campus leaders and engaged citizens. One student whose personal career had taken her from student government into peer counseling said, “Everything builds on itself.” Several students said that they had participated in groups, projects, and events because they were asked to do so. Personalized invitations from faculty, staff, or peers were much more effective than mass mailings and emails. As student leaders, participants in these focus groups also issued many invitations to peers. One said, “In the committees I run, I take people who have the qualities of leaders, and expose them, bring them along in meetings with the Administration.”

If this theory of recruitment followed by habit-formation applies widely, then the most important thing is to make sure that many people are recruited and encouraged to participate in meaningful ways. We should be less concerned about shifts in values as measured by opinion polls (although those might be symptomatic of changes in available opportunities). And we should be more optimistic that if we provide extracurricular groups, service projects, and other civic opportunities, young people will sign up and benefit lastingly.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:21 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

September 8, 2005

against "systematizing" in ethics

In a recent comment, Metta Spencer asks, "I’m ... curious about your notion that systemizing ethical principles is not a good way to go. I would love to hear more about that. I suppose it’s more than just not being a Kantian, but i can't fill in the blanks to guess what you mean, and there aren't citations in these blog thingies." I thought an answer would be worth a full post, so here goes. My position could be summarized as follows:

1. There is a category of concepts that includes the traditional virtues and vices, many institutions (such as marriage and democracy), and many emotions (certainly including love). These concepts have the following features:

a. They are indispensable for moral reasoning. We cannot, for example, do without the concept of "love."

b. They are "thick" terms, in Bernard Williams' sense. That is, they combine fact and value. For instance, to say that someone "loves" someone else is to make a factual claim that is also essentially laden with moral evaluation.

c. They have moral significance, but it is unpredictable. Sometimes their presence makes an act better than it would be otherwise; sometimes, it makes the act worse. (This idea is the heart of Jonathan Dancy's "particularism.")

d. They have vague borders. We can use them effectively to communicate, yet they cannot be defined by pointing to any essential common features. They are examples of what Wittgenstein called "family-resemblance" words.

e. Their vagueness and unpredictability reflect truths about the world, or at least reflect our accumulated experience of life. We know, for instance, that "love" can mean many things and has an unpredictable moral significance. Thus we should not try to gain moral clarity by splitting "love" into two categories (e.g., eros and agape). “Love” is not just the union of two concepts, one good and the other bad. Part of the definition of “love” is that it can be either good or bad, or can easily change from good to bad (or vice-versa), or can be good and bad at the same time in various complex ways.2. If indispensable moral concepts are also unpredictable and vaguely defined, then moral theory has severe limitations, because moral theory is composed of concepts, abstracted from particular circumstances. That is true not only of Kantian theory, but also of utilitarianism and virtue ethics.

3. What justifies the use of a "thick" moral concept in a particular context is not a theory but a story, one that describes what happened earlier and later with reference to people's motivations, purposes, and beliefs. There is much more to say about the logic of narrative and how it supports moral judgment, but my view essentially follows J.L. Austin.

Citations: I advanced part of this argument in a book entitled Living Without Philosophy: On Narrative, Rhetoric, and Morality. However, Dancy's ideas about particularism, acknowledged in that book, are now much more central to my position. My latest views are explained and defended in my manuscript entitled The Myth of Paolo and Francesca: Poetry, Philosophy, and Adultery in Dante and Modern Times, which is out for review by publishers. A summary is online.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:19 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

September 7, 2005

a review

The book that John Gastil and I recently published (as editors), The Deliberative Democracy Handbook, has received its first review on Amazon. I hope it's not the last review, because someone called "environmental planning professor (Virginia, USA)" has written:

I ordered this book hoping that it would indeed be a handbook that would be appropriate for teaching college undergraduates about this exciting approach to problem-solving and capacity-building. With gathering dismay I leafed through the chapters, finding one after another to be merely a collection of breezy comments, written principally by the originator of one or another slightly varying technique, that uncritically promoted the value of that technique. The material appears plucked from a foundation grant proposal. Surprisingly, considering the deep familiarity of the authors with these techniques, the book contains little in the way of actual operational advice. Rather, most of the chapters are unsupported and grandious [sic] claims for the utility of each approach, presumably designed to entice the reader to sign a lucrative consulting contract with the author. Folks, this is why we have academic research - to avoid empty and meaningless self-promoting efforts like this one.

I can't respond without seeming defensive, but this is really quite unfair. First of all, the suggestion that that the authors are after "lucrative consulting contracts" is just mean. Our book has 42 contributing authors, about 38 of whom I know personally. Very few ever see a dime for consulting. All the ones I know struggle at low pay to create constructive opportunities for democratic participation in their communities and countries.

While the Handbook does not provide step-by-step advice, anyone who reads it with any sympathy will recognize a variety of methods and choices. Some chapters describe jury-style deliberations of randomly-selected citizens. Others are voluntary meetings embedded in local associations. Some are online. Some have the power to make binding decisions; others are discussion forums or study circles.

It's true that the chapters are (with roughly three exceptions) written by people who are involved in the projects under discussion. Since they have invested sweat and passion in this work, they are probably biased in its favor. Thus there would have been advantages if we had used independent evaluators. However, that was impossible, since there is not enough money in the field of deliberative democracy to support extensive independent evaluation. Besides, independence has its disadvantages. These chapters are useful--in part--because they clearly express the practitioners' perspective on what they are trying to do. Each chapter is a statement of goals and principles, and each is different from the others.

Moreover, the authors do not simply provide favorable anecdotes, although we did encourage them to begin each chapter with a compelling story or example. The authors also assemble whatever data and evaluation exists, and often they take pains to note drawbacks or unresolved challenges in their work.

In the field of deliberation, it would be useful to have more controlled, experimental studies. Such research could measure the effects of deliberation on individuals' attitudes and behaviors. However, proponents of deliberative democracy are not solely interested in effects on individuals. We also hope that public deliberation will produce better policies, strengthen communities, and educate policymakers. A randomized experiment is not a good tool for assessing such broader outcomes. A combination of normative argument and case studies strikes me as the better approach. Again, there would be advantages to more independent research, but it is also valuable to let practitioners describe and defend their own experiences.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:27 AM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

September 6, 2005

the politics of the New Orleans disaster

I agree with Maria Farrell and others that the New Orleans disaster has displayed aspects of American life that are grievously wrong. People died because they couldn't afford to leave the flooded city. The government failed to help them, just as it had failed to protect them in the first place. The ones left behind were mostly African American and poor. Until the water destroyed their homes, they had lived in one of America's many ghettos: large, socially isolated areas of poverty and high crime, also marked by very poor municipal services, blighted buildings, and a lack of business investment. I don't think there is anything quite comparable to an American ghetto elsewhere in the developed world. There are poor neighborhoods in Europe, often inhabited by people of color. But they are much smaller and less dangerous than the ghettos of the US.

Obviously, these points have ideological significance. It is usually liberal leaders (along with some interesting libertarians, such as Jack Kemp) who emphasize the need to address massive poverty and racial exclusion. When voters observe the New Orleans ghetto after a disaster and recognize the vulnerability of its citizens, they may move leftward. Since the poverty and vulnerability are real, it is quite appropriate to draw ideological and political lessons from what happened this week. It's also important to argue that people in New Orleans were victimized and are not to blame for the rioting. We want Americans to draw the lesson that inner-cities need more investment, not that the police should be more aggressive.

However ....

1) We shouldn't let the issue become narrowly partisan. True, Bush responded to the crisis in a callow and offensive way; yes, his FEMA director is unqualified compared to James Lee Witt, who served under Clinton; and it's a fact that the budget request of the Army Corps of Engineers was not fully funded. But exactly the same kind of disaster and botched response could have happened under Clinton. Besides, the people of New Orleans have been living under Democratic city and state administrations since Reconstruction. Their schools and police force have been terrible all that time. (I would support spending more per student than the $7,533 allocated by the Orleans Parish schools, and a big increase would require more state and federal aid. But New Orleans' per-student spending has increased by 27 percent since 1999 and has risen faster than the national average. The results remain quite poor and cannot be blamed mainly on the feds.)

I doubt very much that it will work as a political strategy to try to focus blame on the Bush administration. In the short term, predictably, voters are divided along partisan lines in their estimate of Bush's performance. There are so many possible targets of blame (including nature, local government, rioters, and long-standing federal policies) that only people who have a particular ideological frame have focused their anger on the president.

In the longer run, voters' opinions of Bush will become irrelevant. I have always assumed that he would be unpopular by now. But his popularity doesn't matter much. Republicans will run as outsiders in 2006 and especially 2008, when they will probably nominate an anti-Washington governor or a Bush critic like McCain for president. As for Democrats, they have a chance to win if they (a) figure out what they stand for and (b) find a plausible candidate. If they succumb to the temptation to bash the outgoing administration, voters will once again conclude that they have no answers to America's problems.

2) We must respond in a way that will make it possible to rebuild New Orleans in a satisfactory way. That is going to require hope and cooperation. Unless individuals feel hope and solidarity, they will do just what Matthew Yglesias predicts and use their insurance money to move away from New Orleans. Hope should come from the fact that America is not simply "selfish and wicked." It is also a robust democracy with comparatively competent government, strong nonprofit institutions, and an impressive tradition of civic innovation. We are much better than we were 25 years ago at city planning, historic preservation, wetland-conservation, and public engagement. We have models like the Listening to the City process, that convened 800 ordinary citizens to help plan the World Trade Center rebuilding. Even the federal government is getting better at engaging the public.

Anger will be part of any public discussions in or about New Orleans, and genuine rage should not be suppressed. But we cannot afford for outsiders to pursue partisan advantage, because the federal, state, and local governments must work together.

3) There should be an ideological dimension to the debates in town meetings, blogs, and op-ed pages, but there is more than one legitimate ideological perspective to consider. I lean toward the view that people in New Orleans are suffering because of our low levels of public investment and our lack of concern for African Americans. But I know libertarians who think that the New Orleans disaster is an illustration of government's hubris. In classic New Deal style, the feds taxed and spent money to build levees and drain swamps, thus encouraging people to live in a dangerous place, against the logic of both market and nature. Burkean conservatives should want to preserve as much as possible of New Orleans' distinctive heritage. Progressives should argue for rebuilding in new and better ways than before. This debate is interesting and important, but it will accomplish little if it narrows to an argument about impeaching George W. Bush (see these comments for a sample).

Posted by peterlevine at 7:23 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

September 5, 2005

Laxdaela Saga: political freedom and psychological insight

On our way to Iceland, I read an Icelandic saga that we happened to have in our apartment (because my wife had read it in college). The sagas were written in the thirteenth century, when Iceland was reasonably well integrated into Christian Europe; but they are set 200-300 years earlier, in the days of the Icelandic Free State. This was an amazing polity, a nation formed by chieftains from Norway, Ireland, and other diverse places and cultures. They met annually at an assembly called the Althing, which functioned as a legislature--writing criminal and civil laws--and a court. They had no executive branch at all. This meant that there were no taxes and no public expenditures on things like temples and churches, roads, or armies. For the same reason, there no police power. The main sentence passed at the Althing was outlawry. An outlaw was supposed to leave Iceland. If he stayed, anyone could kill him.

Me and my girls at Thingvellir, where the Icelandic assembly began meeting in 930

Incidentally, women had a striking degree of freedom and equality. They could divorce at will (although they would only receive half of the property if they showed cause for the divorce); and they represented several of the strongest characters in the saga I read. All the characters seem to care whether husbands and wives had compatible personalities and loved one another--which surely wasn't a priority in early-Modern Europe. Perhaps the hardship of Icelandic life made everyone (including women) indispensable; or perhaps the lack of an executive power prevented women from being dominated.

The Icelandic sagas and their world have attracted distinguished modern theorists with interests in moral philosophy and/or politics and economics: notably, Richard Posner, Alasdair McIntyre, and Jared Diamond. The only primary source I have read is Laxdaela Saga (in translation, of course), but I did find it fascinating. It has a complex plot that can only be described as "realistic." It is about people and their property and relationships. There is almost nothing supernatural or otherwise unbelievable. Perhaps in a society created as an actual voluntary contract--one that preserved a great deal of individual liberty--people became interested in human motives and actions. What Jakob Burkhardt famously wrote of the medieval mind was not true of the Icelanders. He said that in the Middle Ages,

both sides of human consciousness--the side turned to the world and that turned inward--lay, as it were, beneath a common veil, dreaming or half awake. The veil was woven of faith, childlike prejudices, and illusion; seen through it, world and history appeared in strange hues; man recognized himself only as a member of a race, a nation, a party, a corporation, a family, or in some other general category.

In contrast, the sage-authors were like Burkhardt's "men of the Renaissance": "self-aware individuals" who recognized themselves as such. It would be fascinating if their self-awareness arose because they happened to find themselves on an unpopulated island (something like the State of Nature) and negotiated a "liberal" social contract.

I was most surprised by the following feature of the Laxdaela narrative. Gudrun Osvif's-daughter is the central character, a very strong, clever, and passionate woman who marries four times, begins a feud, raises a family, and ultimately becomes Iceland's first nun after the conversion to Christianity. Clearly, she loves Kjartan Olafsson very passionately. She hates his innocent wife and provokes her third husband, Bolli, to kill Kjartan--but we can see that even at that moment she is motivated by her repressed love. The narrator sees this too, and chooses to end the whole saga with her confession to her son: "I was worst to the one I loved most." All of her important acts arise from her unstated passion for Kjartan; but the author does not say so as he (or she?) goes along. Nor does Gudrun or any other character explain her motives explicitly.

It is common enough for a modern novelist to "say and not tell"--in other words, to make a character act consistently as a result of one underlying emotion, but not to explain the reason until the end, if at all. It is also common to explain actions as the results of unconscious and repressed emotions. But I was surprised to find these features in a medieval text. In contrast, the authors of the various Arthurian romances (as I recall) tell us exactly why each character takes each action; yet the knights and ladies act on unpredictable whims. They have little coherence as characters. The author of Laxdaela Saga is both more sophisticated and less explicit about human motivations than his contemporaries in England, Germany, or France. Again, I wonder whether his insightfulness is connected to the political system under which he wrote.

By the way, whatever you do, don't read Laxdaela saga in the "translation" by Muriel Press (1899), even though it's available free on the Internet. The sagas were written is a terse, factual, straightforward, easy style. As Gerald of Wales wrote during the Middle Ages, "this people [the Icelanders] have a truthful and terse speech. They use few and short words" (pdf). But Press uses numerous archaism and coinages, turning the original text into something flowery and obscure: more like late Joyce than Hemingway, who would be a better model.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:48 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

September 2, 2005

why there is looting in New Orleans

I'm quoted in a Baltimore Sun article on that topic today: "Behavior of stressed disaster survivors draws eyes of experts," by Linell Smith. Inevitably, only a snippet of what I said found its way into the story. My blog allows me to state my full view.

Stealing other people's property is wrong. But it is happening on a large scale in New Orleans, because ...

1. Some people are stealing to feed themselves and their children. That is such a strong excuse that it usually cancels the fault. Whether people who steal under such circumstances should even feel regret is a subtle question. A mitigating factor like this is also an explanatory factor: severe need simply causes people to loot.

2. Some people have looted property that was about to be destroyed anyway by the rising water. That doesn't mean that they have a moral right to keep the goods for themselves. But it is both a mitigating and an explanatory factor.

3. People are more likely to steal when other people are stealing as well. If you are the only one committing blatant theft, then you will probably get in trouble. But if everyone else is stealing, then you won't pay a penalty for joining in, and that certainly makes theft more tempting. Besides, if the property is about to be stolen by others, then you will make no difference by taking it yourself. (It's like the situation in which property is about to be destroyed by water; see above). This excuse doesn't justify theft. You should do what is right, not what everyone else is doing. But I believe it's a mitigating factor because the temptation to steal is greater when it's what everyone else is doing.

When I was in college in New Haven, I was waiting one evening on a long line at a convenience store. The lights went out--only in the store, as I recall. You could still see perfectly well. Nevertheless, most people on line took what they had been waiting to purchase, plus a few extra items from nearby shelves, and walked right out. The loss of electric light was a signal that the law was gone: other people were about to steal, so most people joined in. (For enthusiasts of rational-choice theory, this was a Prisoner's Dilemma, and the darkness transmitted a message that enabled people to "cooperate" by looting.)

4. New Orleans may have a weak civic culture, manifested in low levels of trust for other citizens and for institutions. I doubt that many cities could avoid looting under the current circumstances--this must be the worst US natural disaster since San Francisco in 1906. But I do think that a strong civic culture helps when the veneer of civilization is removed, and a weak one hurts. In New York City, the 1965 power failure "was largely characterized by cooperation and good cheer," the blackout in 1977 was "defined by widespread looting and arson," and the latest one in 2003 was again peaceful (sources). These changes track the decline and then the recovery of trust and civility in New York City.

I can't prove that New Orleans has low trust and deep social divisions. The Social Capital Benchmark Survey collected data from Baton Rouge (which scored pretty well), but not the Big Easy. However, New Orleans, for all its charms, has a reputation for high crime, racial division and exclusion, corrupt and violent police, and poorly performing schools. Those problems tend to accompany low trust; and a lack of trust makes people less likely to cooperate when the law disappears.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:15 AM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

September 1, 2005

New Orleans: race and high water

I spent a while this morning trying to juxtapose a good map of race and ethnicity in New Orleans with a satellite map of the flooding there. Actually, the New York Times has an excellent interactive map that does just that. There is a very clear correlation between the areas of deepest water and the highest percentage of African American citizens. This relationship may reflect the fact that White people are able to afford to live on higher ground. Or it may reflect more efforts to protect White citizens from flooding. Or it may be sheer chance. But it's part of the story. See also Kieran Healy on Crooked Timber.

I once wrote an appreciation of New Orleans for this blog that I'd like to cite again.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:04 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack