« July 2005 | Main | September 2005 »

August 31, 2005

pining for the fjords

For the most part, this is supposed to be a professional blog about civic renewal, moral philosophy, and related subjects. However, today I cannot resist recording some of the memories that still fill my mind after two weeks in Scandinavia.

rainbow over Geysir, Iceland

Iceland: I especially recall the southern coast road, two hours of driving on gravel without ever seeing a house, lava fields coated in thin moss on one side of us and the gray Atlantic on the other ... Swimming outdoors on a cold, rainy day, because that's what Icelanders do. A municipal pool, heated by geothermal energy, is a model of Nordic design and a place where people meet to conduct business, steam rising above their bare flesh into the rain. ... A nineteenth-century farmhouse (now preserved as a museum). The respectable front parlor is decorated with wainscotting, severe photographic portraits, and a sofa. The parlor door leads to a dirt tunnel that winds past an open fire pit to a kind of bunker where the animals once sheltered in the long winter: a facade of European gentility concealing extreme hardship.

the fjord at Balestrand, Norway

Norway (the best country to live in): The University quarter in Oslo, with its elegant Regency-style buildings and the healthy, energetic, youthful, and stylish crowds on the streets. ... The rail lines between Oslo and Bergen, which are what every model railroad enthusiast has ever dreamed of creating in his basement: little trains puffing across bridges, through tunnels, around spectacular wooded mountains. ... The view across the fjords from our pension in Balestrand: the sky, the tendrils of fog, the forests, the snow, and the water each form huge swaths of changing color.

Stockholm: This is a fabulous city with a great variety of neighborhoods and sights that we enjoyed for three packed days. But now what I constantly recall is a variation on the following scene: a large expanse of blue-green waves (the city is built on islands and one-third is under water); a horizontal band of stone and stucco buildings, spires, and Mansard roofs behind some moored pleasure boats; and then a great blue sky with fluffy, scuttling clouds, as in a Dutch maritime painting.

On our way back from Stockholm, we flew over snow-capped Norwegian mountains and the fjords, then landed in Reykjavik after seeing a good view of the geysers at the "Blue Lagoon." On the second leg, we noticed the Greenland coast below, dotted with huge icebergs. A few hours later, the pilot noted that Manhattan was clearly visible out of the right windows. And then we landed in a steamy Baltimore summer evening. Everyone says that the Internet has shrunk our world, but to me nothing makes it seem as small as a long airplane ride.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:17 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 30, 2005

the press and political power (thoughts on Jay Rosen/Austin Bay)

Recently, Jay Rosen asked Austin Bay ("Weekly Standard writer, NPR commentator, Iraq War vet, Colonel in the Army Reserve, Republican, conservative, blogger with a lit PhD") to guest-blog about the press, the Bush administration, and the war. Bay's long post provoked a total of 441 comments on Jay's site and 45 on Bay's blog (so far). I haven't read all the comments, but it appears that they generated more heat than light. In particular, there was a lot of passionate discussion of the media's alleged bias against Republicans, little of which--on either side--seemed particularly illuminating. But Bay's original essay was interesting, and I would like to address his thesis from a different angle.

Bay proposes that the United States is locked in an "information war waged by an enemy that is itself a strategic information power," namely, Al Qaeda. The American press has an influence on that war. How it presents the American military, Guantanamo, the Iraqi election, and other key matters will help determine whether people around the world embrace Bin Laden, Bush, or some alternative. And what ideology people adopt is the key question in this "war."

Meanwhile, the Bush Administration and conservatives have a very bad relationship with the mainstream American news media. To a large extent, Bay blames journalists for the poor state of that relationship, arguing that they are biased in liberal, urban, and civilian directions. Nevertheless, he argues, the Bush people need the press to support the long-term struggle against Al Qaeda and Islamic extremism, or else we will fail:

America must win the War On Terror, and the poisoned White House—national press relationship harms that effort. History will judge the Bush Administration’s prosecution of the War On Terror. A key strategic issue for the current White House–perhaps a determinative issue for historians–will be its success or failure in getting subsequent administrations to sustain the political and economic development policies that truly winning the War On Terror will entail.

Bay, a conservative pundit who is angry at the "liberal media" and presents a long bill of specific grievances, nevertheless recommends that the Bush Administration try to improve its relationship with journalists.

Now, here's my response. First, the press powerfully helps or hinders American presidents and administrations in achieving their policy goals. It is not neutral, although it can be diverse. Second, the relationship between the press and the White House has changed dramatically, in ways that make life more difficult for presidents.

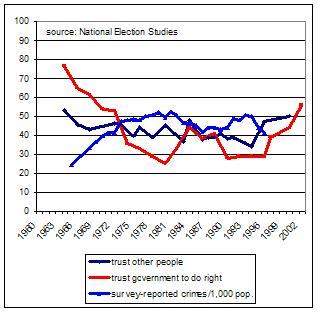

The period from 1945-1965 remains a benchmark for those who want the press to be more supportive of the US military and presidency. But it is important to note that the stars were then aligned to the benefit of presidents Truman, Eisenhower, and Kennedy. There was virtual consensus about foreign policy and national economic policy (which everyone wanted to be Keynsian). To be sure, there were wrenching national debates about Jim Crow and McCarthyism/Communism, but the leaders of the two national parties tended to adopt similar positions on these matters, positions that were also shared by the editors of The New York Times and like publications. All these people knew each other: they were white men who tended to graduate from the same schools and colleges. Reporters were aware of, but left completely unreported, politicians' personal problems and faults. The national press also imposed on itself a set of norms that were then only about 50 years old: nonpartisanship, a separation of news from opinion and fact from fiction, and objectivity (epitomized by the suppression of first-person reporting). Reporters tended to take leaders at face value and report their explicit arguments; they did not reflexively interpret everything a politician said as a ploy to obtain votes. Perhaps most important, the American people trusted the government, as the following trend lines show.

Trust in government correlates with trust in other human beings (r=.17 in the National Election Studies); and many people did trust their neighbors in an age of prosperity, high associational membership, clear memories of World War II, and relatively low crime and divorce. (Note the huge increase in per capita crime after 1963, shown above.) I don't mean to romanticize America ca. 1960, when gross inequalities were papered over. I only want to argue that life was relatively easy for political leaders, because the press and public alike tended to support them and overlook their foibles.

All of this changed after 1965. Public trust in the government fell. The parties became more ideologically consistent and polarized. Public consensus on foreign policy crumbled. As Dan Yankelovich writes in Foreign Affairs, "Americans are at least as polarized on issues of foreign affairs as they are on domestic politics. They seem to have left behind, at least for the time being, the unity over foreign policy that characterized the World War II era and much of the Cold War period. As might be expected, Americans today are split most sharply along partisan lines on many (though not all) aspects of U.S. foreign policy." Particularly interesting is the 43-point gap between Republicans and Democrats on whether the US is "generally doing the right thing with plenty to be proud of" in foreign policy.

After 1965, the press chalked up what Bay calls two "great gotcha successes": Vietnam and Watergate. Perhaps those powerful exposes lowered public trust and helped turn journalists into skeptics of government. Or perhaps--as I suspect--journalists belong to our culture, and America as a whole was turning anti-authoritarian, skeptical of power, and less trusting of human beings in general. The modern journalistic "frame" which interprets all political behavior as strategic and self-interested comes, I think, out of our broader culture and not just out of J-schools and news rooms.

Bay argues this is how the press now operates:

Rule One: Presume the U.S. government is lying–especially when the president is a Republican. Rule Two: Presume the worst about the U.S. military–even when the president is a Democrat. Rule Three: Allegations by 'Third World victims' are presumptively true, while U.S. statements are met with arrogant contempt.

Reflecting on how the national press treated Bill Clinton, or how the Washington Post covers local political leaders (who are mostly African American and Democratic), I would say that the rules are:

Rule One: Presume all powerful people are self-interested, and everything they say and do is calculated to win them votes. Rule Two: Look for scandal and failure in all public institutions: schools, the military, welfare systems, the police. Rule Three: Always report allegations against political leaders (followed by their denials) on the assumption that conflict between potentially victimized citizens and potentially crooked politicians is a major form of "news." Don't pay as much attention when citizens agree with one another or work together to address problems.

Evidently, my take is somewhat different from Bay's, but the difference doesn't matter much. There is little doubt that the modern press makes life more difficult for any American president than it once was. It has not become more difficult to be elected or re-elected. After all, someone has to win, and one side will beat the other at the media game. But it is more difficult to realize an ambitious agenda. I'm not sure that Truman, Eisenhower, and Kennedy could have built the interstate highway system, desegregated schools, conducted large-scale, undeclared "police actions," and imposed 90% marginal income tax rates without a supportive and gentle press. Those days are gone.

So what lesson should we draw? I suspect that many of my readers are glad that trust has fallen, recognizing that the U.S. government has done many bad things when not overseen by a skeptical, watchdog press. If anything, many people wish that the press had been much more skeptical of the Bush administration in the run-up to the Iraq war. (Note that public confidence in government and social trust were relatively high in 2002, just when the press was being deferential.) Many people are glad to see the president's approval ratings fall and the press get tougher.

I fully accept that argument, and yet it strikes me that liberal presidents also have a harder time governing when the press is antagonistic to power. In fact, it isn't because Bush has pursued conservative policies that he has tangled with the press. His tax cuts get relatively little coverage, positive or negative. It was when he embarked on a radical, state-led social experiment by invading Iraq that the press pounced, because journalists are always ready to expose the weaknesses of government. I'm against the war in Iraq, but I'm afraid that the attitudes of the mainstream press that Bay dislikes are actually worse for liberals than for conservatives.

Besides, we do need to win an information war against Bin Ladenism, and journalists ought to figure out what their role is going to be in that struggle.

Their coverage will affect international opinion--as well as domestic opinion about matters like civil liberties. They are not innocent or politically powerless. So where do they intend to stand?

Above all, we might ask whether the big decline in public trust is a good thing. Hamilton proposed as a "general rule" that people's "confidence in and obedience to a government will commonly be proportioned to the goodness or badness of its administration." If that is true, then the decline in trust since 1960 was merely a measure of the falling trustworthiness of government. Perhaps--but again, a failure of government is worse news for liberals than for small-government conservatives.

Posted by peterlevine at 2:08 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 29, 2005

autonomous youth culture

In yesterday's Washington Post, Darragh Johnson has a long article about 14-year-old Calixto Salgado, a devout altar boy, first-generation American of Salvadoran ancestry, nice, soft-spoken guy, and C student. He attends Gaithersburg High School, a large suburban school in a fairly affluent Maryland community (median household income: $60k), where the overall graduation rate is 87.2% (pdf, p. 189), 72% of seniors take the SAT (pdf, p. 40), and college is expected, at least for the White kids. The Latino kids, however, face a lot more challenges. About one third of them score "proficient" on the state exams, compared to 61% of whites (pdf). As for Calixto, he is under intense pressure to join a gang. I feel that I almost know him, since he resembles some of the Salvadoran and Mexican kids I have worked with at Hyattsville's Northwestern High School, which is 23 miles to the southeast across Washington's suburbs.

To varying degrees, adolescents live in their own world, separated from adult life. This is especially true for a person like Calixto, whose parents immigrated from El Salvador and lack knowledge or experience relevant to his life. Besides, gangs like MS-13 try to make youth culture as opaque as possible to parents and other adults, going so far as to require their recruits to commit violent crimes so that they will be tied together in a secret conspiracy. But such tactics are in some ways just extreme versions of the general (modern) adolescent urge to have a separate culture.

It matters enormously what that culture is like and how each student navigates it. According to the Post article, White/Anglo students at Gaithersburg High School recruit youth for groups like Key Club by saying, "It looks great on applications!" There is presumably a fair amount of pressure to do well in school, and respect for those who do. Students who belong to that culture are very likely to go to college and then live another 6-8 decades in affluence, safety, and good health. (In Gaithersburg as a whole, almost half of adults have college degrees--compared to 36% for the US.) But Calixto is "at risk" of entering an alternative gang culture, in which case his future will be far bleaker. The stakes are extremely high.

There are things that parents and schools can do to improve young people's odds. (For example, I'm still enthusiastic about making high schools smaller than Gaithersburg's 2,200 enrollment.) However, to a considerable extent, Calixto and his peers have a problem that only only they can address--collectively. For any individual kid, the pressure to join a gang (for self-respect, for safety, to impress the opposite sex, to satisfy the older brother who's already in) may be overpowering. It's a lot easier to resist pressure if you have company. Most of the school's clubs appear to be dominated by Whites, and Calixto doesn't have the grades to play sports. But if there were groups within the school that were created and led by Latinos, they could become safe havens. Ideally, Latino students could work together to change school policies so that the official anti-gang efforts were more effective.

This is a tall order. I'm suggesting that Latino kids in the DC suburbs should do something harder than anything I have ever done--create an alternative youth culture in the face of MS-13. But that may be their best hope, and it requires civic skills and habits that adults may be able to teach and model. (Indeed, Calixto is a member of an after-school group called Identity that seems to be helping him.) Kids instinctively understand the need to organize, but some have responded to MS-13 by creating rival gangs like Cien Por Ciento Latino and Sangre Pura. Somehow, they need to steer a course between those groups and the Key Club, which is unlikely to help them--or even to admit kids like Calixto.

Calixto's situation underlines why we should care about what people in my business clunkily call "youth civic engagement" and "civic education." Teaching kids to work together effectively can be a deadly serious business. It's for that reason, and not merely because I want young people to know the three branches of government, that I'm in this business.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:25 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 26, 2005

three possible goals for the left

In Norway last week, it occurred to me that the left in modern times has taken three distinct paths, each with a different goal:

1. Reduce alienation. Marx's essential idea was that people should be able to conceive creative concepts and then implement them in the real world. Since individuals cannot realize impressive ideas by themselves, such creativity must be cooperative. In a capitalist system, some people conceive ideas and different people carry them out, and both kinds of people (i.e., capitalists and workers) are constrained by market competition. Therefore, everyone is alienated.

I think there is some truth to this diagnosis; but the main socialist and communist solution--workers' collective ownership of factories and farms--has been largely disastrous. Workers are much less alienated in a Tayota plant than in a Soviet one. If there is a strategy for reducing alienation, it probably involves some combination of the small, voluntary co-ops and land trusts described at community-wealth.org; plus policies to support parenthood (which is relatively unalienated labor), and a dynamic entrepreneurial sector.

2. Increase equality. There are strong theoretical arguments in favor of more economic equality than we have in the USA. My favorite argument goes like this. We are capable of producing enormously more value per hour of work than our ancestors did, not because anything that you and I have achieved ourselves, but thanks to an accumulation of knowledge, technology, and social organization. If you are born to parents with education, capital, savvy, ambition; and if they care about you; and if you live in a nice neighborhood in a developed country; and if you have reasonable genes and luck, then you can benefit hugely from the accumulation of progress. If, however, you lack most or all of these advantages, then you will capture little more value from your work than people did 3,000 years ago. This is unfair.

Therefore, if some beneficent being with superhuman power and intelligence (and an inclination to meddle in our affairs) showed up on earth, it would redistribute goods in a much more equitable way. However, in our actual circumstances, there are some big barriers to redistribution. First, in a country like the United States, the median citizen has enough wealth that he or she is not too enthusiastic about redistribution, which might only benefit those further down the ladder. Citizens of poor countries have even less political leverage over us than our own poor have. Second, redistribution probably reduces economic productivity; and we Americans are deeply committed to prosperity and progress. Third, any political power (e.g., a party or a state) that is capable of greater redistribution is also capable of self-dealing and corruption. As I've noted before, textile workers in Taiwan and Hong Kong earn 10-20 times as much per hour as textile workers in China and Vietnam--two countries where a Communist party monopolized power in the name of equality. Those parties now make their own elites rich by blocking independent unions, a classic example of corruption.

These skeptical arguments don't prove that we have the balance just right in the US in 2005. The standard measure of inequality has increased very substantially since 1980, which suggests that we could do somewhat better.

3. Improve Externalities. That's not a phrase that belongs on a bumper sticker or in a political speech. Nevetheless, the left has made the most progress since 1960--throughout the industrialized world--by mitigating certain negative externalities. An externality occurs when some people have a voluntary exchange that affects other parties who didn't consent to their agreement. The externality is the effect on the third parties. It can be positive: for example, a new downtown store can benefit me even if I never shop or work there, by lowering crime, beautifying my city, providing jobs for my neighbors, contributing taxes, attracting visitors, and so on. An externality can also be negative, and the usual examples are environmental. For instance, smoke can blow from a factory into the lungs of people who never consented to receive it.

The mainstream environmental movement accepts a system of private ownership and free exchange (notwithstanding problems of alienation and inequality), but objects to negative externalities and favors regulation--along with public education and tax breaks--to reduce these problems. This strategy has the great political advantage that it accepts the basic status quo of a market system. It has at least two big disadvantages: it cannot deal with all problems, and it sounds relentlessly negative. The cumulative effect of the environmental movement, for example, has been to suggest that the natural world is deteriorating because of the side-effects of human behavior. The world is getting worse, in short, and all we can do is to mitigate the decline.

But a strategy of improving market externalities can be made positive (as I argued once in a narrower post on environmentalism). In fact, most of the good things in life are positive externalities that arise as side effects of market transactions or as the public effects of people's work in voluntary associations. Much of ethics consists of acting so that one's externalities are positive. We could even define the "commonwealth" or the "commons" as the sum total of our externalities, the negative ones subtracted from the positive ones. Then the question becomes: What combination of regulations, opportunities for collaborative work, and moral education can best enhance the commonwealth?

Posted by peterlevine at 1:20 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 12, 2005

entropy

We are off to Scandinavia until August 26, and I do not intend to post from there. Meanwhile, I leave you with a kind of "e-book"--about half of my long, narrative, formal poem entitled Entropy, now lightly illustrated and formatted to be read easily online. Click here to have a look.

I wrote Entropy in 1999-2001 but have been revising it lately. (I'm not quite finished with the revisions, and that's why the end is not yet online.) I submitted it to many publishers' contests in 2001-2003. It was selected as a finalist three times, but the odds against actually winning--and being published--seemed very low. Meanwhile, I found it difficult to find journals that would even consider running excerpts from a long, plot-driven poem. Hence I am happy to give it away here.

Entropy could be better, and if it were, it would be published by now. In that sense, I have no complaints or regrets. However, I was slightly frustrated that no one mentioned either the plot or the philosophy of the poem in all the correspondence that I received. Every comment, whether positive or critical, concerned the imagery. This response bolstered my prejudice that contemporary poetry is often too narrowly concerned with lyric--with first-person descriptions of images that have emotional significance for the writer. If Entropy has virtues, they are the rather elaborate, original, and (I hope) suspenseful plot; the dozen major characters; and the philosophical structure. This is not lyric.

Entropy posits a fairly serious metaphysics, such as might be argued by a philosopher who sought the truth about our world. It embodies that theory in an invented mythology, with a god to personify each major principle of the system. I don't like allegory, which is conceptual, static, and sterile. Therefore, Entropy puts the myth into motion by introducing contingencies, ambiguities, conflicts, human beings with hopes and despairs: in short, the elements of plot. The metaphysics itself explains why it might be worthwhile to make a plot out of an invented metaphysics.

I have decided to explain some of this structure, without saying so much as to foreclose alternative interpretations, in an "afterword" that is also available via the main page.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:17 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 11, 2005

living wages

The other day, I mentioned that Jim Wallis is promoting the "living wage" as major plank in the Democrats' platform. A living wage law sets a minimum legal salary that's high enough to allow one full-time wage-earner to support a family of three or four at or above the poverty line.

Unions, religious groups, and others on the left have invested a lot of energy in living wage campaigns--giving this policy more attention than other anti-poverty initiatives, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit or expanded coverage for Medicaid. Yet economic theory says that businesses will respond to an increase in the minimum wage by cutting workers. Empirical evidence from a "natural experiment" (when New Jersey raised its minimum wage but Pennsylvania did not) generated ambiguous or controversial results. Indeed, the effects of increasing the minumum wage are likely to be fairly complex--and different for various subgroups of poor people. Whether the net effect is good or not is an empirical question, not to be settled by economic theory alone.

Scott Adams and David Neumark of the Public Policy Institute of California have published a very well written and persuasive paper entitled "A Decade of Living Wages: What Have We Learned?" (Full disclosure: Neumark was part of the controversy about the Pennsylvania/New Jersey natural experiment--arguing that the minimum wage increase was not beneficial.) Their paper finds that local living wage laws tend to increase wages among the lowest-paid workers but also cause employment to fall among the least skilled. Both effects are bigger when the living wage applies in several neighboring jurisdictions. The two effects work at cross-purposes, but the net result is a small reduction in the poverty rate. Evidence suggests that a few of the lowest skilled people lose their jobs, but others in the same family units see pay increases; and the whole poor population gains income, on balance. But not very much income. Futhermore, the families that benefit are those that start close to the poverty line. Those deep in poverty do not gain income--presumably because they are likely to be unemployed.

The evidence about local living wage campaigns cannot tell us what would happen if the national minimum wage were raised. However, the implications of the existing studies are not very impressive. Therefore, I wonder why living wage campaigns have absorbed so much energy. It could be because ...

1. We can envision a living wage at the local level, as a law passed by a city government. Some cities are very liberal, so they are likely to pass these laws. In contrast, the federal government will not do anything very progressive about poverty. And no one is advocating, for example, an earned income tax credit at the local level. But could such a policy work? [See the comment by Nick Beaudrot for a correction; many states do have their own EITC.]

2. Like rent control and environmental protection, the minimum wage is a mandate that government passes for businesses. There is no need to appropriate public funds explicitly for a minimum wage, although the cost of government may rise if the state has to pay more for labor. It's politically easier to pass a mandate than an appropriation. Proponents predict large benefits and minimize the costs. In any case, they say, "corporations" will pay the price (and who likes corporations?). However, most economists reply that the potential benefits of a minimum wage are small, at best, and the price will be paid by consumers and some low-skilled workers.

3. Proponents of the living wage don't like economic theory. Indeed, the dismal science rests on some fundamental assumptions that should be questioned. However, I think the limits of economic theory call for more empirical evidence, especially data drawn from experiments or quasi-experiments. My reading of the available evidence suggests that living wage laws may be mildly beneficial, but they are nowhere close to sufficient.

Posted by peterlevine at 3:00 PM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

August 10, 2005

the September Project (Year II)

I mentioned the September Project last year. On Sept. 11, 2004, people met in hundreds of libraries to conduct civic events as a positive, democratic response to the attacks of 9/11/01. There were voter registration drives, discussions and citizens' forums, performances, and art projects for people of all ages. This page provides many examples, wonderful in their diversity.

The organizers are back at work preparing for Sept. 11, 2005. Their website has evolved to include a blog and other interactive features. (This is the homepage: www.theseptemberproject.org.) Co-director David Silver, formerly a fabulous graduate student at Maryland and now a professor at University of Washington, tells me that 2005 will be different and better than 2004 in the following ways:

Posted by peterlevine at 2:36 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 9, 2005

empathy versus systematic thought

For the second day in a row, here's a response to an opinion piece in The New York Times. The new article, entitled "The Male Condition," has two distracting features. First, it takes Larry Summers' side in the argument about women in science. Second, it's written by someone called Baron-Cohen--not the very funny Sascha, but his distinguished cousin Simon. If you get past Larry and Sascha, the article is as interesting as it is disturbing.

Dr. Baron-Cohen argues that people can be placed on a continuum from systematic to empathetic. "Systemizing involves identifying the laws that govern how a system works. Once you know the laws, you can control the system or predict its behavior. Empathizing, on the other hand, involves recognizing what another person may be feeling or thinking, and responding to those feelings with an appropriate emotion of one's own."

Baron-Cohen says that males are statistically more likely to be systematic; females, to be empathetic. Some of this difference may be cultural, but there may also be a biological factor, since (a) the difference shows up very early in childhood; and (b) it may be connected to the fact that prenatal testosterone correlates negatively with socialibility in young children. If the level of prenatal testosterone affects where one falls on the empathetic-systematic spectrum (which has not been shown directly), then males would tend to be more more systematic and females would tend to be more empathetic, although there would be much variation and overlap.

Three thoughts occur to me in response ...

1) Even if our degree of empathetic versus systematic thinking is ordained by biology or culture, we can still consider when it is better to be systematic or empathetic. Despite being male, I have spent a lot of time arguing against systematic thinking in ethics. I adopted this position because I was persuaded by certain arguments in favor of empathy and against abstract principles. The same arguments don't apply to mathematics or engineering; they only concern ethics. Thus it's possible to be reflective about the role of empathy in various domains and to adjust our thinking accordingly. Which brings me to the second point ...

2) Some leaders, and some cultures, have taken very strong positions on one side or the other of the continuum. Calvin, Lenin, and Khomeini were three men who built whole regimes dedicated to the notion that behavior should be guided by a few principles. Maybe they had a lot of testosterone before they were born, but that's not the point. The point is that historical circumstances favored their vision. In contrast, Aristotle and Hume favored the cultivation of moral sentiments, including empathy. Hume's culture prized sentiments and refined a curriculum designed to make people empathetic.

Presumably, the quantity of prenatal testosterone per capita is pretty stable. Perhaps the amount of systematic versus empathetic thought is also constant--although I have no idea how to measure this. But one thing varies by culture and can be changed through political action: the role of systematic thought in morality and the law.

3. Baron-Cohen ends with a striking hypothesis. He thinks that autism is an extreme form of systematic thinking, resulting (in part) from the union of two parents who are both quite far over on the systematic side of the spectrum. I don't know how plausible this theory is. It does occur to me, however, that it could provide an explanation for the rapid increase in autism reported in industrialized democracies. The rate of what Baron-Cohen calls "assortative mating" (similar people mating with each other) has perhaps increased as people have begun to marry members of their own profession. Even forty years ago, an engineer would most likely be a man who would marry a woman of the same social origins but quite different skills. Today, there is a higher probability that he will marry another engineer--perhaps a woman from a very different background, but with similar mental proclivities.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:22 AM | Comments (3) | TrackBack

August 8, 2005

Jim Wallis' "message"

Since November, many Democrats have asked Jim Wallis, the editor of Sojourners magazine, to help them develop a moral message--one that might reduce the Republican advantage among religious voters. Wallis says that he has been telling them to change their policy proposals, not just their rhetoric. He writes:

the minority party has been searching, some would say desperately, for the right 'narrative': the best story line, metaphors, even magic words to bring back electoral success. The operative term among Democratic politicians and strategists has become 'framing.' How to tell the story has become more important than the story itself. And that could be a bigger mistake for the Democrats than the ones they made during the election.... What are your best ideas, and what are you for--as opposed to what you're against in the other party's message? Only when you answer those questions can you figure out how to present your message to the American people.

This is 100% right, in my opinion. Wallis provides an additional service by sketching out the main points of a liberal agenda that is explicitly moral. He has prompted the right discussion, but his proposals raise questions for me.

For example, Wallis recommends that the Democrats set a target of cutting the number of abortions in half. This would move them past the Clinton-era slogan that abortion should be "safe, legal, and rare." It could potentially give them very broad support on the abortion issue, because they would safeguard the right to terminate a pregnancy while also telling "pro-life" voters that they (and they alone) had a plan to cut the actual number of abortions.

But would the policy work? Wallis recommends "adoption reform, health care, and child care; combating teenage pregnancy and sexual abuse; improving poor and working women's incomes; and supporting reasonable restrictions on abortion, like parental notification for minors (with necessary legal protections against parental abuse)." Democrats (including me) like it when the number of abortions falls because women have better welfare and more real choices. We do not like the number to fall because of legal restrictions, even "reasonable" ones. I could imagine embracing a policy that included both sides of the coin, as long as most of the reduction in the abortion rate came from the additional social support, not from the new legal limits. What do we know about the relative impact of those two kinds of proposals? For instance, would "adoption reform" really help?

Wallis also recommends that the Democrats take on poverty. Indeed, it is remarkable how little John Kerry said about the poor and near-poor, given that he was the candidate of the center-left. Even though the median family income of American voters is well above $50,000, I believe that some voters would respond to moral language about poverty, which would pay off politically.

Again, the issue is not what people want--they want less abortion and less poverty--but how to achieve that goal. Wallis is angry about "wartime tax cuts for the wealthy, rising deficits, and the slashing of programs for low-income families and children." So am I. However, changing the distribution of wealth through the tax code only helps if the government spending is beneficial. Some programs help poor people, but others are wasteful or even counterproductive.

Wallis recommends a national "fair wage": in other words, an increase in the federal minimum wage. There's controversy about this proposal, but it appears that "moderate minimum wage increases do not reduce poverty rates," partly because most of the lowest-paid workers are teenagers who are not poor, and partly because employers cut benefits when the minimum wage goes up. Bigger than "moderate" increases might reduce poverty; then again, they might increase unemployment.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities estimates that existing spending programs--mainly, Medicaid, the Earned Income Tax Credit, Food Stamps, and Supplemental Security Income--prevent 27 million Americans from being poor. Nevertheless, about 31 million remain poor, and many more are near-poor. It is quite likely that we could help more people if we expanded the existing programs, although that requires separate evidence. Furthermore, I doubt that many Americans would be inspired by a call to increase spending for Medicaid or the EITC. Who has more innovative and persuasive proposals?

Posted by peterlevine at 7:24 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 5, 2005

ideology in academia and elsewhere

In September, I am supposed to give a talk that's essentially about the relationship between academics and other citizens. Based on anecdotal experience, I assumed that professors tended to be secular, internationalist, and skeptical of capitalism, whereas the median American was religiously Christian, nationalist, and pro-market. That gap in opinion would affect debates about spending on higher education, academic freedom, and the role of scholarship.

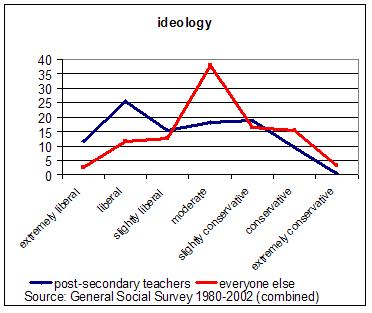

I wanted to go beyond personal impressions, if possible. The General Social Survey allows us to compare the political views of people by their profession. In order to include enough "post-secondary teachers" in the sample to get statistically meaningful results, I had to combine all years from 1980 to 2002. That is a misleading method if there were big changes in the professoriat over those 22 years. However, I still find the results interesting.

The first graph (above) shows the distribution of self-reported ideology among professors and everybody else. Non-professors formed a bell curve during the period 1980-2002, with the median at "moderate" and roughly symmetrical tails in either direction. Professors were far more liberal.

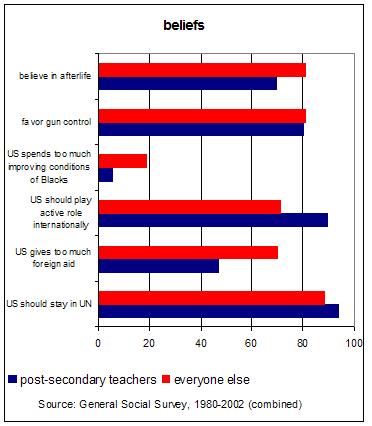

This comparison could be misleading if professors defined "liberal" differently from other people. However, a second graph provides direct evidence about opinion on issues.

Professors had about the same views of gun control as everyone else (presumably because most people favored it). On all other issues, professors were more liberal--although not by gigantic margins.

[Update, 9/29: Chris Uggen offers better data than I provide above--although my data are also relevant--and he scores some good points in arguing that the ideological tilt in sociology is a real problem.]

Posted by peterlevine at 11:28 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

August 4, 2005

teaching the First Amendment

According to a Knight Foundation study released earlier this year (based on more than 100,000 surveys) only 51 percent of high school students believe that "newspapers should be allowed to publish freely without government approval of stories." This kind of finding brings to mind Judge Learned Hand's caution, delivered to a large crowd in Central Park on “I Am an American Day,” May 21, 1944--two weeks before D-Day. Judge Hand said, "I often wonder whether we do not rest our hopes too much upon constitutions, upon laws, and upon courts. These are false hopes; believe me, these are false hopes. Liberty lies in the hearts of men and women; when it dies there, no constitution, no law, no court can even do much to help it."

If young people don't believe in the First Amendment, free speech may not be safe for long, especially since attitudes toward rights (and other large social issues) tend to form in adolescence and remain pretty durable.

However, good work is underway. Knight is behind a new Teach the First Amendment website that provides access to free course materials and lesson plans, a quiz of student knowledge, links to advocacy work in support of civic education (including the Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools), and assistance in helping to start student media projects. The last element is important: the Knight study found that students who were personally involved in newspapers or broadcast work were more supportive of free speech.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:40 AM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

August 3, 2005

service-learning: latest research

Service-learning, which is present in 44 percent of American high schools, means a combination of community service with academic work on the same topic. For example, students may volunteer in a homeless shelter while reading articles about homelessness and writing papers on the subject. I am a proponent of this approach, having devoted much of my own discretionary time to a service-learning project. However, I think we proponents should squarely face research findings about service-learning that raise serious questions. In the light of these findings, not our message but our practice probably needs to change.

For instance, CIRCLE sponsored a recent study by Shelley Billig, Sue Root, et al. that was unusual in that it actually compared service-learning students to comparable students in regular social studies classes. (Very little service-learning research is comparative). Billig et al. found that service-learning kids were significantly more likely to say they intended to vote and that they enjoyed school. These were two positive results, but on the many other indicators, the service-learning students scored the same as the comparison group. Moreover, there was much more variation among the service-learning classes, with some scoring high above--and others, far below--the average. The more effective service-learning classes were taught by teachers who had been using that approach for a long time. There was less variation in the regular social studies programs.

Clearly, there is some good news in the study. Among other things, schools need not sacrifice academic knowledge by using experiential education, because kids in the service-learning program scored as well as the comparison group on knowledge questions. On the other hand, if I were a school administrator who did not have a prior commitment to service-learning, this is what I would probably say in response to the study:

"I am going to allow service-learning, because some of my teachers who are dedicated to it get quite good results. I don't want to sacrifice those results or discourage a subculture of my teachers who are motivated to use community-service in their classes. However, I'm not going to do much to encourage service-learning, either. After all, it's likely to be expensive and possibly controversial. On average, we can get the same results using more conventional approaches. Moreover, the existence of some real dud projects in service-learning makes me think that quality might decline if we tried to increase the frequency of this approach. It's good for self-selected teachers and perhaps self-selected kids, but it's not for the mainstream. If anything, I believe we need less service-learning with more quality control."

This kind of response--based on the most recent comparative research--should be something of a wake-up call for those of us in the service-learning business.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:55 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 2, 2005

the EPA and public involvement

On several occasions, the US Environmental Protection Agency has managed to involve a wide variety of citizens in addressing local problems. This approach was already evident in 1983, when EPA Administrator William Rickelshaus created a deliberative forum that allowed the citizens of Takoma, WA to make their own collective decision about whether to close a dangerous copper smelter at the cost of local jobs. Recently, EPA launched a Public Involvement website that summarizes the Agency's experience and provides questionnaires and other tools for practical use.

Perhaps the most interesting feature for a non-specialist is the list of case-studies, and particularly the cases of "community-based environmental protection." When environmental problems broaden beyond "point-sources" (such as factories and large sewage pipes) and include homes and small businesses, it is necessary to get whole communities involved in environmental protection. Participation must be voluntary or it will never work. Fortunately, it is sometimes possible to find common ground among people with different interests and cultures--for example, environmentalists and ranchers in the West. The by-product of such successful deliberations and collaborations can be stronger communities. The EPA's database is full of good examples.

Posted by peterlevine at 6:47 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 1, 2005

Tony Blair and the Doctrine of Double Effect

Reflecting on the July 7 bombings, the leftist MP George Galloway (on whom I have written before) said, "London has reaped the involvement of Mr. Blair's involvement in Iraq." Most people to Galloway's right--which means most people--think he is wrong to blame Blair for the terrorism. Yet it seems likely that a causal chain does connect the bombings to British participation in the Iraq invasion. Extremist Muslim radicals attacked UK targets only once they had become incensed by the presence of British "crusaders" in Iraq. The use of terrorism against civilian British targets was a fairly foreseeable result of the invasion and occupation.

I wouldn't try to deny Blair's causal role, but I would argue that someone can be a cause of something without being morally responsible for it. Blair set in motion a chain of events that led to the bombings, but the bombers are completely responsible for what they did, and Blair is completely innocent of it. Thomas Aquinas' Doctrine of Double Effect comes in handy here. The New Catholic Encyclopedia, as quoted in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, explains that the Doctrine excuses an act (in this case, the invasion) that has bad results under these conditions:

1. The act itself must be morally good or at least indifferent. 2. The agent may not positively will the bad effect but may permit it. If he could attain the good effect without the bad effect he should do so. The bad effect is sometimes said to be indirectly voluntary. 3. The good effect must flow from the action at least as immediately (in the order of causality, though not necessarily in the order of time) as the bad effect. In other words the good effect must be produced directly by the action, not by the bad effect. Otherwise the agent would be using a bad means to a good end, which is never allowed. 4. The good effect must be sufficiently desirable to compensate for the allowing of the bad effect.

Thus, to take Tony Blair's side, we would say: The act of invading Iraq to remove Saddam Hussein was morally good. Even if its net consequences turn out to be bad for Iraq (mainly because of the incompetent US leadership), British participation was well-intentioned and reasonable. Blair did not will a terrorist response to the invasion, even if he had reason to predict it. The removal of Saddam was a direct consequence of the invasion; the London bombings were highly indirect results. Finally, the end that Blair willed was sufficiently good to compensate for the death of Londoners.

The Doctrine is relevant to other current events as well. For example, last Friday, the IRA promised to renounce violence. Did the Doctrine of Double Effect ever excuse its use of terror? Alison McIntyre would say "no." She writes in the Stanford Encyclopedia article, "The terror bomber aims to bring about civilian deaths in order to weaken the resolve of the enemy: when his bombs kill civilians this is a consequence that he intends." Thus bombing a pub or train station is a bad act with a bad intention, and the Doctrine never excuses it.

However, McIntyre thinks that bombing campaigns undertaken by people in uniform can be permissible under the Doctrine. She writes, "The strategic bomber aims at military targets while foreseeing that bombing such targets will cause civilian deaths. When his bombs kill civilians this is a foreseen but unintended consequence of his actions. Even if it is equally certain that the two bombers will cause the same number of civilian deaths, terror bombing is impermissible while strategic bombing is permissible."

Supporters of the IRA deny this distinction. They argue that it's unfair to defend established nations with large budgets that drop bombs from airplanes--yet damn individuals as "terrorists" if they kill smaller numbers of people with car bombs.

Of course, one response is that no one has the right to kill anyone else except in the most immediate self-defense. Then the Doctrine of Double Effect would not cover the IRA, but it wouldn't excuse Tony Blair, either. By invading Iraq, he willed the death of Iraqis (and Brits); a pacifist would deny him that right. But the true pacifist would also say that Neville Chamberlain impermissibly willed the death of civilians when he declared war on Hitler. Once we admit that someone can cause death for a good reason, then we are either "consequentialists" (i.e., we assess acts by subtracting their costs from their benefits), or we subscribe to the Doctrine of Double Effect.

In the last few months, three different people have told me that the IRA bombings had a good consequence: they brought the British and the Unionists to the bargaining table. I do not know whether this is true or whether the same result could have been obtained by peaceful means. Consequentialist reasoning might possibly rationalize the IRA bombings, but not those of Hamas and the other Palestinian terrorist groups. It seems to me that suicide bombings in Israel and the Occupied Territories have had one overall consequence: Israel has begun to build a security fence. Thus Hamas indirectly caused the fence. For consequentialists, that makes Hamas responsible for damage to Palestinian national interests--which is indeed what I believe. However, according to the logic of the Doctrine of Double Effect, Hamas might be causally responsible for the fence, yet Israel might have sole moral responsibility for it.

(See also a good short article by William Soloman from the Encyclopedia of Ethics.)

Posted by peterlevine at 6:42 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack