« March 2011 | Main | May 2011 »

April 29, 2011

the character of poets and of people generally

In Coming of Age as a Poet (Harvard, 2003), Helen Vendler interprets the earliest mature verse of four major poets: Milton, Keats, Eliot, and Plath. She argues that great poets reach maturity when they develop consistent diction and formal styles; favored physical and historical milieux; major symbolic referents; characters or types of characters whom they include in their verse; and some sort of (at least implicit) cosmology. They often retain these combinations to the ends of their careers.

Robert Lowell provides an example (mine, not Vendler's). From the 1940s until his death, his characteristic milieu is New England--specifically the coastal region from Boston to Nantucket--over the centuries from the Puritan settlement to the present. His diction mimics the diverse voices of that region's history, from Jonathan Edwards to Irish Catholics, but he brings them into harmony through his own regular rhymes and rhythms. His major symbolic references include gardens, graveyards, wars of aggression, the Book of Revelation, and the cruel ocean. He avoids presenting a literal cosmology, but he describes several worldviews in conflict. Sometimes, the physical and human worlds are cursed or damned and we are estranged from an angry, masculine God. Other times, the world is a garden: organic, fecund, and pervasively feminine. (See my reading of The Indian Killer's Grave for detail.)

A combination of diction, favored characters, milieux, subjects of interest, value-judgments, and a cosmology could be called a "personality." I don't mean that it necessarily results from something internal to the author (a self, soul, or nature-plus-nurture). Personality could be a function of the author's immediate setting. For instance, if Robert Lowell had been forceably moved from Massachusetts to Mumbai, his verse would have changed. Then again, we often choose our settings or choose not to change them.

A personality is not the same thing as a moral character. We say that people are good or virtuous if they do or say the right things. Their diction and favorite characters seem morally irrelevant. For example, regardless of who was a better poet, Lowell was a better man (in his writing) than T.S. Eliot was, because Eliot's verse propounded anti-Semitism and other forms of prejudice, whereas Lowell's is full of sympathy and love.

So we might say that moral character is a matter of holding the right general principles and then acting (which includes speaking and writing) consistently with those principles. Lowell's abstract, general values included pacifism, anti-racism, and some form of Catholic faith. Eliot's principles included reactionary Anglicanism and anti-Semitism--as well as more defensible views. The ethical question is: Whose abstract principles were right? That matter can be separated from the issue of aesthetic merit.

I resist this way of thinking about virtue because I believe that it's a prejudice to presume that abstract and general ideas are foundational, and all concrete opinions, interests, and behaviors should follow from them. One kind of mind does treat general principles as primary and puts a heavy emphasis on being able to derive particular judgments from them. Consistency is a central concern (I am tempted to write, a hobgoblin) for this kind of mind. But others do not organize their thoughts that way, and I would defend their refusal to do so. What moral thinking must be is a network of implications that link various principles, judgments, commitments, and interests. There is no reason to assume that the network must look like an organizational flowchart, with every concrete judgment able to report via a chain of command to more general principles. The hierarchy can be flatter.

To return to Lowell, one way of interpreting his personality would be to try to force it into a structure that flows from the most abstract to the most concrete. Perhaps he believed that there is an omnipotent and good deity who founded the Catholic church when He gave the keys of heaven to Peter. Peter's successors have rightly propounded doctrines of grace and nature that are anathema to Puritans. Puritans massacred medieval Catholics and Native Americans who loved nature and peace. Therefore, Lowell despises Puritans and admires both medieval Catholics and Wampanoags. In his diction, he mocks Puritans and waxes mournful over their victims. His poetic style follows, via a long chain of entailments, from his metaphysics.

But I think not. It is not even clear to me that Lowell, despite his conversion to Catholicism, even believed in a literal deity. (Letter to Elizabeth Hardwick, April 7, 1959: "I feel very Montaigne-like about faith now. It's true as a possible vision such as War and Peace or Saint Antony--no more though.") The point is, literal monotheism did not have to be the basis or ground of all his other opinions, such as his love for and interest in Saint Bernard or his deep ambivalence toward Jonathan Edwards. Those opinions could come first and could reasonably persuade him to join the Catholic Church. By mimicking the diction of specific Puritans in poems like "Mr Edwards and the Spider," Lowell could form and refine opinions of Puritanism that would then imply attitudes toward other issues, from industrial development to monasticism.

Poets are evidently unusual people, more self-conscious and aesthetically-oriented than most of their peers, and more concerned with language and concrete details than some of us are. As a "sample" of human beings, poets would be biased.

But they are a useful sample because they leave evidence of their mental wrestling. Poetry is a relatively free medium; the author is not constrained by historical records, empirical data, or legal frameworks. Poets say what they want to say (although it need not be what they sincerely believe), and they say it with precision.

I think the testimony of poets at least suffices to show that some admirable people begin with concrete admirations and aversions, forms of speech, milieux and referents, and rely much less on abstract generalizations to reach their moral conclusions. Their personalities and their moral characters are one.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:24 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 28, 2011

Not Quite Adults

Richard Settersten and Barbara E. Ray have published Not Quite Adults: Why 20-Somethings Are Choosing a Slower Path to Adulthood and Why It's Good for Everyone (Bantam 2010). Their book is a product of the MacArthur Research Network on Transitions to Adulthood and Public Policy, an ambitious collaborative project that also yielded, among many other works, an article by Constance Flanagan and me on "Civic Engagement and the Transition to Adulthood."

Not Quite Adults is admirably broad, accessible, and well-written, enriched by the stories and voices of real people. (The Network conducted 500 interviews). It begins with a vignette of a typical young person of 30 or 50 years ago, who left home and started life immediately after high school graduation. Today, in contrast, half of 18-24-year-olds still live in the bedrooms where they were children. The ages at which people become financially independent, move out of their parents' homes, marry, vote, and finish their final degree have all risen rapidly.

One response is to view all these young people as slackers or immature. But that overlooks the profound difficulties young Americans face today in becoming independent. It also overlooks the many ways in which the third decade of life can be a valuable time for learning, developing skills and networks, and contributing to society. Finally, it overlooks serious gaps in the experience of different groups of young people. Some--Settersten and Ray call them "swimmers"--are using their young adult years to strengthen their positions, racking up advanced degrees and social networks before they settle into careers and families. This is all to the good (as long as their expectations of success aren't excessive, leading to disappointment). Others--whom the authors call "treaders"--struggle to move through the cross-currents of economic insecurity. For them, the third decade of life is increasingly difficult, and they need social investment. Settersten and Ray point to Youth Build, Youth Corps, and Civic Justice Corps as examples of programs that need more support.

The book has its own interactive website, including a blog on which Rick Settersten asks most recently, "Why do so many Americans have it out for young people?" At a time when many of the basic indicators of young people's well-being (crime, violence, teen pregnancy, and drug use) have been improving, older Americans seem convinced that the new generation is a threat. Asked to discuss "youth," working class Americans immediately identify behavioral problems--violence, crime, lack of respect for adults and for themselves--while elites are just as concerned about low test scores and dropout rates. Meanwhile, the data on young people suggest substantial improvement.

Posted by peterlevine at 3:42 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 27, 2011

college students expect service, study abroad, and extracurricular clubs but report stress and low emotional health

Using data from the College Freshman Survey of the Higher Education Research Institute (HERI), John H. Pryor reports that incoming college freshmen are increasingly likely to expect that they will participate directly in extracurricular activities, community service, and foreign study--all experiences that have civic purposes and benefits.

But the same study also shows that incoming college students report increased levels of stress and historically low levels of emotional health. A record-high proportion of incoming freshmen (73%) say that the "chief benefit of a college education is that it increases earning power."

For institutions of higher education, these trends raise several questions: Are we meeting the expectations of our incoming students? Can meaningful service activities be antidotes to stress and poor psychosocial well-being? Can they enhance students' economic opportunities? Or do some students report being "overwhelmed" because they are pursuing civic experiences as well as academic work and jobs?

(Cross-posted from the CIRCLE homepage.)

Posted by peterlevine at 8:11 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 26, 2011

the Campaign for Stronger Democracy

The Campaign for Stronger Democracy pulls together activists for campaign and election reform, deliberative democracy, transparency, collaborative governance, civic education, national and community service, and community organizing. It is an unprecedented coalition, the need for which I tried to demonstrate rigorously through an exercise in network mapping. The Campaign's monthly newsletter is turning into my favorite compendium of relevant articles. You can register for the free newsletter here.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:15 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 25, 2011

the Eight Americas

Christopher Murray and six colleagues have published an article entitled "Eight Americas: Investigating Mortality Disparities across Races, Counties, and Race-Counties in the United States." They divide the entire US population into the following categories:

1. Asian: Asians living in counties where Pacific Islanders make up less than 40% of total Asian population

2. Northland low-income rural white: Whites in northern plains and Dakotas with 1990 county-level per capita income below $11,775 and population density less than 100 persons/km2

3. Middle America: All other whites not included in Americas 2 and 4, Asians not in America 1, and Native Americans not in America 5

4. Low-income whites in Appalachia and the Mississippi Valley (with 1990 county-level per capita income below $11,775)

5. Western Native American: Native American populations in the mountain and plains areas, predominantly on reservations

6. Black Middle America: All other black populations living in countries not included in Americas 7 and 8

7. Southern low-income rural black: Blacks living in counties in the Mississippi Valley and the Deep South with population density below 100 persons/km2, 1990 county-level per capita income below $7,500, and total population size above 1,000 persons (to avoid small numbers)

8 High-risk urban black: Urban populations of more than 150,000 blacks living in counties with cumulative probability of homicide death between 15 and 74 [years] greater than 1.0%

Disparities in life expectancy are enormous--for example, women in America 1 outlive men in America 8 by 20 years. It is illuminating to view these empirically-derived categories instead of the usual baskets (such as White versus African American). Below is my chart of selected disparities from the article:

Posted by peterlevine at 2:22 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 22, 2011

what would Jane Addams say?

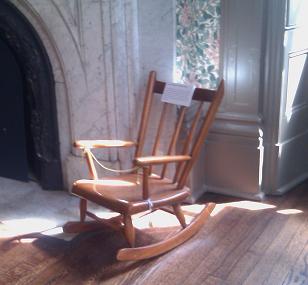

This is the tiny rocking chair in which Jane Addams learned to read as a little girl, encouraged by her father, John ("double-D") Addams, who served in the Illinois State Legislature with Abraham Lincoln.

This is the tiny rocking chair in which Jane Addams learned to read as a little girl, encouraged by her father, John ("double-D") Addams, who served in the Illinois State Legislature with Abraham Lincoln.

Zoom out to Jane Addams' bedroom, decorated with a painted portrait of Tolstoy and wallpaper in the William Morris style. That room is at the head of the stairs in the gracious Italianate Victorian building known as Hull-House where Addams lived for many years.

Zoom further out to the neighborhood where once the Hull-House Settlement, a whole complex of public buildings around green courtyards, once served its neighborhood of tenement houses, factories, and outdoor food markets. "Served" is not really the right word, because the neighbors co-created Hull-House and all of its programs with Addams. Their neighborhood was flattened--quite literally--in the 1960s to make room for the spare modernist blocks of the University of Illonois at Chicago.

Addams always kept her distance from universities. It is an irony that UIC was built on the bulldozed buildings of Hull-House, after the latter had taken its unseccessful fight to survive all the way to the US Supreme Court. But today UIC is a diverse, engaged, urban research university--not much like the University of Chicago from which Addams kept a critical distance. So perhaps the irony is not so painful.

Zoom further out to follow my taxi en route from Addams' house to Midway Airport. Soon we pass the Cook County Juvenile Detention Center, built with beds for 500 although it often houses 800 young people amid rampant vermin and loose ceiling tiles that can be used as missiles.

We cross a vibrant Mexican-American shopping street, each storefront brightly decorated, and then return to quiet working-class districts of brick homes. Next comes the Cook County Jail, set on 96 acres of city land, housing 9,800 inmates and employing more than 10,000 people, ringed by double coils of concertina wire. Family members wait in line by the maximum security wing.

And then vast industrial lots near the railway yards--historic sources of Chicago's wealth and its solid jobs. The lots are still huge and busy, but now machines handle the containers and move the heaps of gravel. Hardly a human being is visible for blocks at a time, although I spot a fat black cat hunting in the tall weeds.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:00 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 21, 2011

building web communities for policy discussion

(Chicago, IL) I am here to visit the impressive Institute for Policy and Civic Engagement at the University of Illinois at Chicago. (It is located right near my favorite shrine to American democracy, Jane Addams' own Hull House.) Among its many activities and projects is a whole web portal, civicsource.org, that is devoted to policy-relevant information and discussion, plus training modules and tools that help citizens to engage. It just launched, but the IPCE and the urban research university that it represents have the human resources to make it a rich source of news, ideas, and tools.

Meanwhile, AmericaSpeaks, on whose board I am honored to serve, has launched The American Square, a social network/discussion forum "devoted to enabling respectful, multi-partisan conversation about policy and politics." The organizers say, "We will find real solutions to real problems rather than on sound bites, ego, and demonization of those who disagree with us."

Posted by peterlevine at 11:24 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 20, 2011

what is the role of public education in youth civic engagement?

(Posted at Logan en route to Chicago) Here I am addressing the question of whether parents or schools have the right to influence kids politically--a classic issue in political theory. I suggest that empirical research is relevant as well:

Posted by peterlevine at 10:36 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 19, 2011

a constitutional amendment for campaign finance reform

After the Supreme Court's decision in Citizens United v Federal Election Commission, which gave corporations unlimited rights to spend money to influence elections, I am leaning in favor of a constitutional amendment to permit the regulation of campaign finances. The need will be even more pressing if the Court overturns Arizona's system of public funding for candidates, as appears likely.

But it will not be easy to get the amendment right (even imagining that it can pass). Although spending should not be equated with free speech, regulating campaign spending does raise genuine First Amendment issues. Unchecked by courts, Congress could deliberately set the spending limit so low that incumbents would be safe. Or worse, it could ban some groups from spending while setting no limits on others. That is why the Supreme Court should have approved reasonable campaign finance laws (applying First Amendment scrutiny) and allowed us to leave the Constitution alone.

If we must amend the Constitution, I'm not sure I favor the leading proposal, which says: "Congress shall have power to set limits on the amount of contributions that may be accepted by, and the amount of expenditures that may be made by, in support of, or in opposition to, a candidate for nomination for election to, or for election to, Federal office." (It also grants similar powers to state legislatures and gives Congress the right to enforce the limits.)

Would this text allow Congress to set a spending limit of $1 and prohibit any advertising? (Given incumbents' ability to send free mailings and obtain free news coverage, they have incentives to set low limits.) Would this text permit Congress to ban newspapers from running articles "in support of" candidates? Perhaps a court would balance the new amendment with the First Amendment, but I am not sure that the plain text cited above would allow such balancing.

I lack the expertise and experience to write a better amendment, but I think it would have to invoke such principles as fairness to challengers and reasonable access to communications media, so that courts could strike down inappropriate limits. Ultimately, I am less enthusiastic about limits than about public funding for campaigns--which is fully constitutional until the Supreme Court says otherwise.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:37 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

April 18, 2011

Elizabeth Bishop, At the Fishhouses

The Poetry Foundation provides the text of Bishop's masterpiece "At the Fishhouses" (1948) along with a recording of the author reading it (not necessarily as well as it could be read).

She introduces the color silver early and returns to it often. In fact:

- All is silver: the heavy surface of the sea,

swelling slowly as if considering spilling over ...

But nothing in the poem is actually silver. That is just an appearance, a misleading feature of the surface of things. For instance, "the silver of the benches ... is of an apparent translucence ..." The wheelbarrows look beautifully silver because of the "small iridescent flies crawling on them."

The opposite of false silver is the profound and true depth of the sea. "Cold dark deep and absolutely clear" is the comma-free phrase that Bishop strikingly repeats. The temptation in the poem is to plunge through silvery appearances to the real "element bearable to no mortal," the ocean water that would kill by freezing or drowning. It is a temptation that Bishop suggests early and then repeatedly defers or avoids. Immediately after first invoking the "cold dark deep," she digresses:

- ... One seal particularly

I have seen here evening after evening.

He was curious about me. He was interested in music;

like me a believer in total immersion,

so I used to sing him Baptist hymns.

Singing Baptist hymns to a seal is amusing. Even if you don't happen to find it funny (as I do), I think you will agree that it has the form of a joke, meant to deflect the question of how to relate to the "clear gray icy water" that would ache your bones and burn your hand if you entered it. Buried in the joke is the serious idea of "total immersion." Plunging into the ocean at Nova Scotia would be like facing the ultimate truth that we try to defer. Of that water, Bishop writes,

- It is like what we imagine knowledge to be:

dark, salt, clear, moving, utterly free ...

If silvery surfaces and deadly depths are two crucial ideas in the poem, a third is the human observer. The poem begins with apparently objective and scientifically precise description. But then the narrator comes in:

- The old man accepts a Lucky Strike.

He was a friend of my grandfather.

We talk of the decline in the population

and of codfish and herring. ...

The narrator, like all mortal beings, inhabits a world of change. All the things she observes have developed and will cease, like the wheelbarrows that have come to be "plastered / with creamy iridescent coats of mail" or the cod that will disappear from overfishing. The last line of the poem says explicitly that "our knowledge is historical, flowing, and flown." You cannot truly experience the freezing depths without dying in them: a metaphor for the unbearableness of truth. The poem is about flinching.

Bishop's mentor Marianne Moore had written "A Graveyard" about a similar view of the ocean. In that poem, an unnamed man stands in the way of the sea, annoyingly blocking the view. But Moore tries to forgive him because it is natural to want to immerse oneself:

- it is human nature to stand in the middle of a thing

but you cannot stand in the middle of this:

the sea has nothing to give but a well excavated grave.

In Bishop's poem, the ocean seems to come from a living source, even a human one:

- drawn from the cold hard mouth

of the world, derived from the rocky breasts

forever, flowing and drawn ...

I would normally resist a biographical interpretation, but Bishop inserts herself in the poem ("he was a friend of my grandfather") and reminds us that human knowledge is temporal and personal. So it is relevant that Elizabeth Bishop had to move to her grandparents' home in Nova Scotia at age five, after her father had died and her mother was institutionalized with mental illness. In this poem, the frigid, salty water flows from breasts that should feed a daughter warm, sweet, sustaining milk. The metaphor (stated in a line of iambic pentameter) is agonizingly lonely. But Bishop's seal friend, her grandfather's dwindling connections, her love of surfaces--"beautiful herring scales"--, her subtle homage to Marianne Moore, and the writing of the poem itself show how we can digress and postpone what we know that we know.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:16 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 15, 2011

the disappearing center

This chart from Alan I. Abramowitz, The Disappearing Center (Yale, 2010) deserves attention:

Turnout has risen for people who strongly identify with parties and has fallen for those who do not. Or ... people who vote have become more attached to parties, while people who don't vote have moved into the Independent column. Or some of both. As a result, an Independent is likely to be a non-voter and a voter is likely to be a partisan. This was far from true in the 1950s. I am not sure whether the trend is good or bad, but it is an important explanation of politics today.

(All the turnout rates shown above are exaggerated because of social desirability bias, but the relationships among partisanship, year, and likelihood of voting should be valid).

Posted by peterlevine at 6:11 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 14, 2011

Nancy Pelosi with my book

The Minority Leader with Tufts Trustee Alan Solomont at Tufts. She is pointing out that the hands on the cover of my book The Future of Democracy are of many colors.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:26 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

John Gaventa on invited and claimed participation

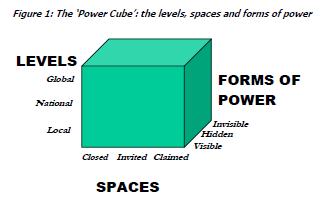

Today, I will be interviewing John Gaventa at a Tisch College forum to which all are welcome. Gaventa has been a major figure in democracy and popular education since his student days in the early 1970s. One of his recent contributions is the PowerCube, a simple device that activists can use for analysis and planning:

I am especially interested in the dimension that runs from "closed" to "invited" to "claimed." Much of my work has involved trying to get powerful institutions to "invite" public participation by, for example, reforming elections to make them more fair, enhancing civic education, advocating changes in journalism, or recruiting citizens to deliberate about public policy. Increasingly, I believe that democratic processes must be claimed, not invited, if they are to be valid and sustainable.

For instance, in 2009, angry opponents of health care reform deliberately disrupted open "town meetings" convened by Democratic Members of Congress. The Stanford political scientist James Fishkin published an argument for randomly selecting citizens to discuss health care instead of holding such open forums. That was a classic proposal for "invited" democracy. The New York Times chose to give his essay the headline, "Town Halls by Invitation." I would now say that democratic participation cannot be by invitation--it must be a right claimed or created by ordinary people, whether elites like it or not.

On the other hand, when officials do invite participation, that is often in response to public pressure or demand. In such cases, formally "invited" spaces are actually claimed ones. One of the most important innovations is Participatory Budgeting (PB). As I understand it, the Labor government of Porto Allegre, Brazil, invented PB to reduce political pressure on itself as it faced hard budget choices. But PB became so popular that it survived changes of party control in Porto Allegre and spread to many other municipalities around the world. In such cases, reform begins with an invitation but becomes an expectation.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:05 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 13, 2011

my testimony in favor of lowering the voting age to 17 in Lowell, MA

Students in Lowell have fought to get the city council to support lowering the voting age to 17 for municipal elections. They persuaded the Lowell Sun newspaper to change its position from opposing the reform to supporting it (pdf). Today, scores of them traveled to the Massachusetts State House to testify before the committee that must review Lowell's petition. I testified in support of their efforts.

Testimony of Peter Levine before the Joint Committee on Election Laws, April 13, 2011

Chair Finegold, Chair Moran, members of the Joint Committee on Election Laws, thank you for giving me the opportunity to testify in support of bill H01111 (“persons seventeen years of age or older be authorized to participate in certain elections in the city of Lowell”). I will speak briefly because the effective advocates and real experts are the students who have already talked today.

I direct CIRCLE (the Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning & Engagement), which is part of Tufts University in Medford. CIRCLE is the nation’s leading nonpartisan research center devoted to young people’s civic education and political participation.

The research evidence suggests that it may be very beneficial to lower the voting age to 17. People from around the United States and other countries are constantly asking CIRCLE whether that reform would work. I commend the students from Lowell, the City Council, and other Lowell leaders for wanting to experiment with it. I believe that its effects would be positive, but I also think it is an excellent idea to try the reform in one city where there is enthusiastic support and then evaluate the impact. We have an existing partnership with UTEC in Lowell and would be happy to help study the effects of lowering the voting age there.

I would be happy to answer any questions about the research, but in my allotted time, I will mention briefly that:

• Today, we expect young people to vote for the first time when most are living away from older adults who could remind them to participate, help them with the mechanics, and discuss issues with them. They are living with other people who have never voted before. That is a recipe for low turnout, and the effects are lasting, because research shows that voting is a habitual behavior.

• Voting for the first time while they are still in school would allow students to learn the mechanics of registration and voting (which many find intimidating) and to experience nonpartisan discussions of important issues before their first election. In one experiment, teaching young people how to vote raised their turnout in a local election by 17 points, even though that election occurred months later. Lowell has a strong commitment to civic education in its schools.

• Seventeen-year-olds are ready to vote. Americans at age 17 score about the same on questions about political knowledge, tolerance, political efficacy, perceived civic skills, and community service as 21-year-olds. I know of no evidence that they score lower than 50-year-olds.

• You may have read that adolescents’ brains differ from older people’s brains in ways that affect their decision-making. But voting is not like steering a car. The kinds of premeditated, abstract decisions that people make in the ballot box are not affected by age. On the contrary, adolescents are just as capable of making those decisions wisely as older people are.

Sources:

Elizabeth Addonizio, “Reducing Inequality in Political Participation: An Experiment to Measure the Effects on Youth Voter Turnout,” presented at the American Political Science Association, 2004.

Mark N. Franklin, Voter Turnout and the Dynamics of Electoral Competition in Established Democracies since 1945, Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Daniel Hart and Robert Atkins, "American Sixteen- and Seventeen-Year-Olds are Ready to Vote," Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 63 (January 2011), pp. 201-221

Eric Plutzer, “Becoming a Habitual Voter: Inertia, Resources, and Growth,” The American Political Science Review 96/1 (March 2002), pp. 4

Posted by peterlevine at 6:23 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 12, 2011

defunding civic education

From what I am hearing, the budget deal negotiated by Congress and the President had the following effects on civic education:

Learn & Serve America, the program within the Corporation for National and Community Service that funds "service-learning" in k-12 schools, colleges and universities, nonprofits, and Native American communities, was eliminated completely--after 21 years of work.

The Center for Civic Education, a national nonprofit whose primary source of funds for decades has been the United States Department of Education, was allocated no money. I think the entire civic education portfolio in the Department was zeroed out.

The Teaching American History grant program (which mainly supports educational opportunities for teachers of k-12 history) was cut by about 36 percent.

I have been critical of the way some of these funds were used in the past; improvements are possible. But for the national government to invest nothing in the civic education of young people is unacceptable.

For other cuts that affect democratic processes in the United States, see the Campaign for Stronger Democracy.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:26 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 11, 2011

ideology affecting market behavior

You might think that ideology affects what you say, but not where you put your dollars. Nothing like an investment decision to clear the head and focus your mind on empirical data. But just before the federal shutdown was averted last Friday, CNN reported that investors weren't concerned. "The shutdown talk is noise," said Jeffrey Saut, chief investment strategist for Raymond James in St. Petersburg, Fla. "It really won't have a major effect on the economy. The government is unproductive. Everybody already knows that."

I thought that story was good news at the time. I expected a shutdown and was glad to read that markets wouldn't fall. But Mr. Saut's literal claims are very debatable. First, even if the government were totally unproductive, it is a massive consumer and employer. If it fails to pay any bills, that will have a deleterious impact on the parts of the economy that Mr. Saut thinks are productive (including his own financial services sector). Second, government can be productive. It funded the invention of computers, founded the Internet, and built the interstate highway system. Even some routine services have impressive payoffs. A random-controlled study of an educational program called Quantum Opportunities found that its net benefits were $28,427 per student, a pretty good return. I have no stake in claiming that the government is more productive than other economic sectors, such as banking. But it seems purely ideological to dismiss its positive impact impact on the economy as zero on the basis that "everyone knows" it isn't productive.

I wrote a post in fall 2010 about how investment advisers were bullish, claiming that divided government would bring "stability." That claim seemed un-empirical to me. Various forms of turmoil and unpredictability were likely to follow from Republican control of the House, not the "stability" that investment banks wrote about in their prospectuses.

So I return to two rival hypotheses:

1. These people really believe what they literally say, and it affects their behavior. They think that a market shutdown won't affect markets because the government is unproductive, and therefore it won't affect markets.

2. These people find palatable ways to convey what they actually think--not that Republican control will bring stability or that a shutdown will have zero impact on markets, but rather that Republican control means lower taxes for them, and a shutdown could strengthen Republicans' hands in negotiating fiscal policy.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:31 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 8, 2011

the MIT Global Challenge

Amos Winter is a Tufts grad (2003) who has invented the Leveraged Freedom Chair, a cheap, rugged, three-wheeled chair that people can use to get around the dense cities and countryside of the developing world. He will be speaking (with a bunch of others, including me) at the Tisch College 10-year anniversary celebration tomorrow.

Winter studied at MIT, which is the host of the MIT Global Challenge. Student teams develop solutions to profound human and environmental problems and compete for prizes in an open online vote. Near the top of the competition right now are the Indian Mobile Initiative, which will engage Indian engineering students in developing socially useful applications for cell phones; the InnoBox Science and Engineering Kit, which is a cheap and portable kit for doing science experiments, meant for classrooms in South Africa; and BodyNotes, a tool that allows an amputee (in the US, Sierra Leone, or anywhere else) to communicate with a distant expert about fixable problems--like soreness and infection--by emailing photos.

The most obvious benefits of projects like these are the tools themselves, devices and projects that markets would not generate because the end-users are too poor. There may be benefits for the designers as well: technical skills, understanding of the world, and moral growth. Finally, many of the projects build strong and reciprocal partnerships among very different groups of people. For example, the Indian Mobile Initiative doesn't propose any particular applications, but rather a process by which Indian students will collaborate to develop software. These dialogues and exchanges take more-than-technical skills to create and should produce more-than-technical benefits.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:05 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 7, 2011

Frontiers of Democracy: Innovations in Civic Practice, Theory, and Education

The Third Annual Conference in Civic Studies at Tufts, Co-sponsored by The Deliberative Democracy Consortium, The Democracy Imperative, and the Tisch College of Citizenship.

Please join us for this two-day gathering of educators and activists to explore the theory and practice of citizenship. (It will begin in the evening of July 21 and conclude in the afternoon of July 23). Through interactive sessions, we will focus on "citizenship" as creativity, agency, and collaboration - not as a form of membership that separates those who are in from those who are out.

Join us for a series of learning exchanges, presentations, and conversations on:

- Engaging—and being engaged by—the online public: How are online technologies being incorporated into democratic governance and education?

- The "neutrality" challenge: Concerns over neutrality challenge educators and practitioners alike. In public life, the question is how to balance the commitment to a politically neutral process with the desire to achieve more equitable outcomes. In the classroom, the question is how to present all perspectives on an issue yet take a definitive stance in an effort to educate for democracy. What are the politics of neutrality, on campus and in public life?

- What role is there for innovative theory in civic practice? For example: how might Elinor Ostrom's Nobel-prize-winning research on "common pool resources" help citizens, public officials, and other leaders share the work of sustaining deliberative democracy.

Scholars, students, activists, educators and others interested in this topic are welcome to use this form to apply to attend. Registration costs $120, $30 for students. Free admission for participants in the Summer Institute of Civic Studies. Scholarships are available for select applicants who demonstrate financial need.

ABOUT THE CONFERENCE

The Civic Studies, Civic Practices Conference concludes the third annual Summer Institute of Civic Studies at Tisch College. This intensive, two-week interdisciplinary seminar brings together advanced graduate students, faculty and practitioners from diverse fields of study for challenging discussions about the role of civics in society.

DRAFT SCHEDULE

For a draft conference schedule (subject to change), please see this page.

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

For information about practical matters, please visit our FAQ page.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:07 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 6, 2011

harnassing institutions to serve communites' knowledge needs

These are some notes for my talk at an MIT conference tomorrow. Most in the audience will be librarians, joined by various practitioners and scholars of new media.

The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation got its money from newspapers. The Knight brothers were in the newspaper business, and the Foundation has made substantial investments in the profession of journalism. But journalism (as we once knew it) is in crisis, and the Foundation realizes that the public interest is best served not by trying to save newspapers or reporters, but by finding the most effective means to meet the real needs that newspapers, at their best, have served. Hence in 2007 the Foundation launched The Knight Commission on the Information Needs of Communities in a Democracy.

In turn, the Commission was wise enough to realize that "information" is only a piece of the problem. Information is inert: all by itself, it doesn’t produce judgment, motivation, decisions, actions, or power, let alone wise decisions and beneficial actions. Already in 1934, T.S. Eliot was asking prophetically:

- Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge?

Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?

Today, information is available in such profusion that our chief problem may be TMI, too much information, not too little. According to a recent article in Science by Martin Hilbert and Priscila López, if all the information created so far by human beings were entered on high-density compact disks, the pile of disks would reach past the moon.

I acknowledge that some important information is unavailable, either because no one has invested in producing it or because powerful elites are keeping it secret, and we still need to fight for information. Librarians and journalists are among the people who wage that fight on the public's behalf. But access to information is far from our only need. As the Knight Commission found:

- Skilled people, appropriate technologies, and reliable and relevant information are the building blocks of a successful communications environment. What generates news and information in that environment, however, is not just those building blocks. It is engagement--specifically, people's engagement with information and with each other.

I think that when people "engage," some of the things they do include:

- Discussing information with other people, including people who have different values and interests, in order to make sense of it;

- Using their knowledge to help them manage public resources, run organizations, and work on public problems together. In turn, their experiences as they work together generate information, knowledge, and understanding;

- Recruiting other people, including young people, to be interested and concerned about important public issues and giving them the skills they need for interpretation, analysis, collaboration.

I start with the bias that we need institutions for these purposes. I am open to the idea that we need institutions less than we used to, because now we have virtual networks (like Facebook, or the Internet itself) that cut the costs of discussion collaboration. But I see no evidence that these networks have yet revived our democracy. And I think the tough questions to ask are:

- Can a loose, voluntary network really recruit people who lack motivation and interest in public affairs?

- Can a loose voluntary network reliably bring people into conversation with others who are different from themselves?

- Can a loose voluntary network be accountable to all its members in a fair way?

- Can a loose, voluntary network hold governments and businesses accountable consistently, over time?

There was never a golden age of American democracy, but we did once have pervasive institutions that recruited members, got them interested in public affairs, digested and interpreted information for them, encouraged them to talk and reach their own conclusions, and brought their members into conversation with people who were different. In the 1970s …

- about 65 percent of Americans said they read the newspaper every day. They might subscribe for the classifieds, the comics, or the sports, but a newspaper had an incentive to interest them in public affairs and provided a dose of commentary and debate.

- almost 30 percent of Americans or their spouses belonged to labor unions. They joined because their workplaces were unionized, but the union had incentives to interest them in politics and to develop their political skills.

- more than 60% of Americans said they had attended a face-to-face meeting within the past year, thanks in large part to the prevalence of identity organizations, from the Knights of Columbus to the NAACP. Like newspapers and unions, these groups recruited, trained, interpreted information, and encouraged discussion.

The various streams of civic life didn't flow together often enough, but there were times when unions and chambers of commerce, priests and rabbis, journalists and politicians, met and talked with one another within their own communities.

But all of these institutions have fallen on very hard times, shedding most of their members and resources. So we need to leverage new institutions for similar purposes. Here are three ideas, derived from the Knight Commission report but expanded by me:

1. A Communications Corps.

Literally millions of young Americans are involved today in structured community service programs, whether service-learning classes in their schools or universities, after-school programs like 4-H and Campfire Girls, or the full-time positions supported by AmeriCorps. This is a powerful infrastructure.

Young people tend to have relatively strong skills for using digital media, which they could contribute to serve their communities. But, being young, they have relatively narrow knowledge of public life. Thus they have much to learn by serving their communities' information needs.

Existing service programs range in quality, but some are insufficiently challenging. The programs would educate better if they had more ambitious learning objectives.

The Knight Foundation recommend a "Geek Corps": college students would serve nonprofits by providing IT support. I would amend that proposal in two ways. I would open the corps to non-college youth, recognizing that only about one quarter of our young adults really have the four-year college experience, and their peers (including the one third who drop out of high school) also have much to contribute. In fact, given limited resources, I would focus on young adults who have never attended college.

Second, I wouldn't make it a "geek" corps, implying a focus on setting up servers and tweaking software. I would make it a "communications corps," with a heavy emphasis on making videos, writing text, interviewing neighbors, and facilitating online discussions. Corps members would still be assigned to local nonprofits, but their job would typically be to produce videos for the website, not to get the office network running.

One model is a free-standing corps, parallel to YouthBuild, City Year, Public Allies, ViSTA and the like. I would be more inclined to infuse the communications work into the programs of these existing "corps," while employing a relatively small number of youth as full-time trainers and developers who would serve the rest of the service world.

2. Universities as Community Hubs

Higher education is a big sector, with $136 billion in annual spending and $100 billion in real estate holdings. But it is not just any big business. Its fundamental mission is the production and dissemination of knowledge and the promotion of dialogue and debate.

But universities need to dedicate themselves to their own communities' knowledge needs, not only in abstract statements, but as a matter of real investment. Providing timely information of local relevance and with input from neighbors trades off against other intellectual pursuits. Overwhelmingly, rewards and prestige flow to scholars whose work is original and generalizable. Communities need work that is true, relevant to them, and accessible to them. Universities can produce some of both, but they cannot add more local work without subtracting a bit of something else. Creating community information hubs within higher education requires at least a modest shift of priorities.

Universities must also aggregate the scattered knowledge produced by their professors, students, and staff. One of the advantages of the traditional metro daily newspaper was its format--a manageable slice of information every day, with the top news on the front page, a few hundred words of debate in the letters column, and space for the occasional in-depth feature. In contrast, a great modern university produces a flood of material for an array of audiences. Universities need to think about common web portals that accumulate and organize all their work relevant to their physical locations.

They must adopt appropriate principles and safeguards. You can do good by going forth into a community to study it, to portray it, and to stir up discussion about it. Or you can do harm. Much depends on how you relate to your fellow citizens off campus. Relationships should be respectful and characterized by learning in both directions. In this context, "research ethics" means far more than the protection of human subjects from harm; ethical research is directed to genuine community interests and needs and builds other people’s capacity for research and debate. Like faculty, students must be fully prepared to do community service well, and held accountable for their impact.

3. Sustained Face-to-Face Dialogue in Communities

Face-to-face discussions of community issues have been found to produce good policies and the political will to support these policies, to educate the participants, and to enhance solidarity and social networks. They turn mere information into public judgment and public will. I am still moved by the Australian participant in a planning meeting who said, "I just can’t believe we did it; we finally achieved what we set out to do. It's the most important thing I’ve ever done in my whole life, I suppose."

Hampton, VA, the fourth-place winner in the international Reinhard Mohn Prize for the best civic engagement process in the world, exemplifies what sustained, embedded deliberation looks like. Hampton did not just invite citizens to participate in one high-profile discussion that was somehow linked to policymaking. Instead, Hampton has a mosaic of school counsels, neighborhood councils, police councils, a Youth Commission, public city planning processes, Participatory Budgeting (where large groups of citizens allocate capital spending). It also provides relevant training opportunities, including civic education in the schools and a suite of courses for adults called "Diversity College."

I would draw the conclusion that is also implicit in the title of Carmen Sirianni’s recent book, Investing in Democracy. You can't get community dialogues on the cheap. They take a long-term effort and resources that are normally a mixture of money, policies, and people’s volunteered or paid time.

There must be some kind of organizer or convening organization that is trusted as neutral and fair and that has the skills and resources to pull off a genuine public deliberation. Libraries and universities are among the institutions that can play that role.

People must be able to convene in spaces that are safe, comfortable, dignified, and regarded as neutral ground. Again, libraries and universities can help.

There must be some reason for participants to believe that powerful institutions will listen to the results of their discussions. They may be hopeful because of a formal agreement by the powers that be, or even a law that requires public engagement. Or they may simply believe that their numbers will be large enough--and their commitment intense enough--that authorities will be unable to ignore them. In the terms of John Gaventa's Power Cube, the discussions cannot be "invited." They must be "created" or "claimed."

There must be recruitment and training programs: not just brief orientations before a session, but more intensive efforts to build skills and commitments. Ideally, moments of discussion will be embedded in ongoing civic work (volunteering, participation in associations, and the day jobs of paid professionals), so that participants can draw on their work experience and take direction and inspiration from the discussions. There must be pathways for adolescents and other newcomers to enter the deliberations.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:47 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 5, 2011

why it is good to talk to people across the political spectrum

Three lively discussions about civic education within two weeks: one at the CUNY Graduate Center in Manhattan, the next at James Madison's Montpelier, the third in DC. A similar topic, but the participants came from very different places on our wide political spectrum.

At CUNY, at least one participant believed that No Child Left Behind was a right-wing strategy to privatize all public schools. (The theory goes: once schools fail to meet the Adequate Yearly Progress benchmarks, students will be given vouchers.) Another speaker simply called charter schools "private" and saw them as a manifestation of creeping market fundamentalism. I don't know whether these views represented consensus in the room, but no one challenged them. There was some talk about trying to revive the "open classroom" movement of the 1970s. A distinguished and experienced scholar said that he had expected Barack Obama's election to change everything, but when that failed, he was now ready to give up on politics.

At Montpelier, at least one participant felt that any federal intervention in education is unconstitutional (because education is not listed among the enumerated powers). Thus to try to influence the federal government to support civic education would be to mis-educate our students, who should be learning that the government has wantonly exceeded its constitutional limits. No Child Left Behind is a liberal plot to get the federal government deeply implicated in our schools. There was much talk about teaching the founding documents of the Republic. Some people felt that we should stay out of politics and policy completely and instead create small, alternative spaces where teachers and students could explore first principles.

These contrasting thoughts clear one's head, challenge one's clichés, and take one back to first principles. What is the proper role of a national government in civic education? What should students learn, and how? And how can we even consider national standards, if our adults disagree so profoundly about the core purposes of education?

(The participants in DC seemed less explicitly ideological to me, perhaps because they were much more numerous, predominantly centrist, and focused on pending policy changes.)

Posted by peterlevine at 2:32 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 4, 2011

why political recommendations often disappoint: an argument for reflexive social science

In an essay entitled "Why Last Chapters Disappoint," David Greenberg lists American books about politics and culture that are famous for their provocative diagnoses of serious problems but that conclude with strangely weak recommendations. These include, in his opinion, Upton Sinclair's The Jungle (1906), Walter Lippman's Public Opinion (1922), Daniel Boorstin's The Image (1961), Allan Bloom's Closing of the American Mind (1987), Robert Shiller's Irrational Exuberance (2000), Eric Scholsser's Fast Food Nation (2001), and Al Gore's The Assault on Reason (2007). Greenberg asserts that practically every book in this list, "no matter how shrewd or rich its survey of the question at hand, finishes with an obligatory prescription that is utopian, banal, unhelpful or out of tune with the rest of the book." The partial exceptions are works like Schlosser’s Fast Food Nation that provide fully satisfactory legislative agendas while acknowledging that the most important reforms have no chance of passing in Congress.

The gap between diagnosis and prescription is no accident. Many serious social problems could be solved if everyone chose to behave better: eating less fast food, investing more wisely, using less carbon, or studying the classics. But the readers of a given treatise are too few to make a difference, and even before they begin to read they are better motivated than the rest of the population. Therefore, books that conclude with personal exhortations seem inadequate.

Likewise, some serious social problems could be ameliorated by better legislation. But the readers of any given book are too few to apply sufficient political pressure to obtain the necessary laws. Therefore, books that end with legislative agendas disappoint just as badly.

The failure of books to change the world is not a problem that any single book can solve. But it is a problem that can be addressed, just as we address complex challenges of description, analysis, diagnosis, and interpretation that arise in the social sciences and humanities. Every work of empirical scholarship should contribute to a cumulative research enterprise and a robust debate. Every worthy political book should also contribute to our understanding of how ideas influence the world. That means asking questions such as: "Who will read this book, and what can they do?"

Who reads a book depends, in part, on the structure of the news media and the degree to which the public is already interested in the book’s topic. What readers can do depends, in part, on which organizations and networks are available for them to join and how responsive other institutions are to their groups.

These matters change over time. Consider, for example, a book that did affect democracy, John W. Gardner's In Common Cause: Citizen Action and How It Works (1972). After diagnosing America's social problems as the result of corrupt and undemocratic political processes and proposing a series of reforms, such as open-government laws and public financing for campaigns, Gardner encouraged his readers to join the organization Common Cause. He had founded this organization two years earlier by taking out advertisements in leading national newspapers, promising "to build a true 'citizens'' lobby—a lobby concerned not with the advancement of special interests but with the well-being of the nation. … We want public officials to have literally millions of American citizens looking over their shoulders at every move they make." More than 100,000 readers quickly responded by joining Gardner's organization and sending money. Common Cause was soon involved in passing the Twenty-Sixth Amendment (which lowered the voting age to 18), the Federal Election Campaign Act, the Freedom of Information Act, and the Ethics in Government Act of 1978. The book In Common Cause was an early part of the organization’s successful outreach efforts.

It helped that Gardner was personally famous and respected before he founded Common Cause. It also helped that a series of election-related scandals, culminating with Watergate, dominated the news between 1972 and 1976, making procedural reforms a high public priority. As a book, In Common Cause was well written, fact-based, and clear about which laws were needed.

But the broader context also helped. Watergate dominated the news because the news business was still monopolized by relatively few television networks, agenda-setting newspapers, and wire services whose professional reporters believed that a campaign-finance story involving the president was important. Everyone who followed the news at all had to follow the Watergate story, regardless of their ideological or partisan backgrounds. In contrast, in 2010, some Americans were appalled by the false but prevalent charge that President Obama's visit to Indonesia was costing taxpayers $200 million per day. Many other Americans had no idea that this accusation had even been made, so fractured was the news market.

John Gardner was able to reach a generation of joiners who were setting records for organizational membership.* Newspaper reading and joining groups were strongly correlated; and presumably people who read the news and joined groups also displayed relatively deep concern about public issues. Thus it was not surprising that more than 100,000 people should respond to Gardner's newspaper advertisements about national political reform by joining his new group. By the 2000's, the rate of newspaper reading had dropped in half, and the rate of group membership was also down significantly. The original membership of Common Cause aged and was never replaced in similar numbers after the 1970s. John Gardner's strategy fit his time but did not outlive him.

Any analysis of social issues should take account of contextual changes like these. Considering how one’s thought relates to the world means making one's scholarship "reflexive," in the particular sense advocated by the Danish political theorist Bent Flyvbjerg. He notes that modern writers frequently distinguish between rationality and power. "The [modern scholarly] ideal prescribes that first we must know about a problem, then we can decide about it. … Power is brought to bear on the problem only after we have made ourselves knowledgeable about it."** With this ideal in mind, authors write many chapters about social problems, followed by unsatisfactory codas about what should be done. As documents, their books evidently lack the capacity to improve the world. Their rationality is disconnected from power. And, in my experience, the more critical and radical the author is, the more disempowered he or she feels.

Truly "reflexive" writing and politics recognizes that even the facts used in the empirical or descriptive sections of any scholarly work come from institutions that have been shaped by power. For example, in my own writing, I frequently cite historical data about voting and volunteering in the United States. The federal government tracks both variables by fielding the Census Current Population Surveys and funding the American National Election Studies. Various influential individuals and groups have persuaded the government to measure these variables, for the same (somewhat diverse) reasons that they have pressed for changes in voting rules and investments in volunteer service. On the other hand, there are no reliable historical data on the prevalence of public engagement by government agencies. One cannot track the rate at which the police have consulted residents about crime-fighting strategies or the importance of parental voice in schools. That is because no influential groups and networks have successfully advocated for these variables to be measured. Thus the empirical basis of my work is affected by the main problem that I identify in my work: the lack of support for public engagement.

Reflexive scholarship also acknowledges that values motivate all empirical research. Our values--our beliefs about goals and principles--should be influenced and constrained by what we think can work in the world: "ought implies can." Wise advice comes not from philosophical principles alone, but also from reflection on salient trends in society and successful experiments in the real world. An experiment can be a strong argument for doing more of the same: sometimes, "can implies ought." If there were no recent successful experiments in civic engagement, my democratic values would be more modest and pessimistic. If recent experiments were more robust and radical than they are, I might adopt more ambitious positions. In short, my values rest on other people’s practical work, even as my goal is to support their work.

Finally, reflexive scholarship should address the question of what readers ought to do. A book is fully satisfactory only if it helps to persuade readers to do what it recommends and if their efforts actually improve the world. In that sense, the book offers a hypothesis that can be proved or disproved by its consequences. No author will be able to foresee clearly what readers will do, because they will contribute their own intelligence, and the situation will change. Nevertheless, the book and its readers can contribute to a cumulative intellectual enterprise that others will then take up and improve.

*In 1974, 80 percent of the "Greatest Generation” (people who had been born between 1925 and 1944) said that they were members of at least one club or organization. Among Baby Boomers at the same time, the rate of group membership was 66.8%. The Greatest Generation continued to belong at similar rates into the 1990s. The Boomers never caught up with them, their best year being 1994, when three quarters reported belonging to some kind of group. In 1974, 6.3% of the Greatest Generation said they were in political clubs. The Boomers have never reached that level: their highest rate of belonging to political clubs was 4.9% in 1989. (General Social Survey data analyzed by me.)

**Bent Flyvbjerg, Making Social Science Matter (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), p. 143

Posted by peterlevine at 8:20 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 1, 2011

participatory budgeting in Recife, Brazil wins the Reinhard Mohn Prize

The best civic engagement process in the world is participatory budgeting in Recife, according to 11,600 German citizens who voted for their favorite among a set of impressive nominees. In "participatory budgeting," large groups of citizens deliberate and vote to allocate municipal capital budgets. Many evaluations have found juster decisions, much lower corruption, and higher levels of democratic legitimacy as outcomes.

I consulted on the Reinhard Mohn competition and also nominated Hampton, VA for the prize. Hampton came in fourth (in the world) with 1,935 votes. I liked Hampton because the city has systematically embedded deliberation and public participation in most of its systems--education, policing, budgeting, parks and recreation, and planning--for decades. Hampton now also uses participatory budgeting.

On the other hand, I understand what the German voters were thinking. Brazil is the birthplace of participatory budgeting, which is one of the most impressive democratic innovations of the last quarter century. Recife seems to be the best example--notable (among other things) for having a separate youth participatory budget. As one astute voter wrote, "In this project I was particularly impressed by the children’s citizen budget. This makes it possible for people to experience and learn about the basic principles of democracy from a very young age. Anyone growing up with that experience will naturally engage in democratic processes as an adult."

Posted by peterlevine at 10:26 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack