« October 2010 | Main | December 2010 »

November 30, 2010

Three C-s of Education Petition Campaign (College, Career and Citizenship)

From the Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools:

The Campaign is sponsoring a petition campaign to remind all policymakers of the essential and historic role schools play in providing the knowledge, skills and disposition for informed and engaged citizenship. The goal of education is more then preparing students for higher education and a successful career; equally important is the role schools play in providing civic participation skills. We are calling this the "Three C-s of Education Petition Campaign." This petition is designed to remind policymakers and the public of the essential civic mission of schools. The petition language is attached. We ask you all to sign the petition. We also ask all associated with CMS to publicize the petition widely through your communication networks. We encourage those with websites to place the petition 'widget' on your site, providing a link to the petition page. The petition drive was launched at the annual conference of the National Council for the Social Studies where well over 1,500 signatures were gathered. This petition will be presented to local, state and federal education policymakers in 2011.

Click to sign:

Posted by peterlevine at 9:10 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 29, 2010

American exceptionalism

Newt Gingrich, Sarah Palin, Mike Huckabee, Mitt Romney, and Rick Santorum agree: the president and his allies in Washington deny "American exceptionalism" in a way that is unprecedented (Huckabee), "truly alarming" (Gingrich), or "misguided and bankrupt" (Romney). As for the president, he was catapulted to national fame by his 2004 speech in favor of American exceptionalism.* Apparently, everyone must propound some version of this doctrine; to doubt it is dangerous business.

For myself, I am not sure that our particular recipe of social policy is, overall, the best one available today. But I am sure that no group (whether a team, a firm, or a country) succeeds in fierce competition by constantly reaffirming that it already does everything better than everyone else and that no loyal member may doubt its superiority on all fronts. That is the intellectual style of GM ten years ago or of the British Empire before 1900. It is the pride that comes before the fall.

My old boss Bill Galston thinks Republicans have introduced the exceptionalism issue (with remarkably little textual basis) as "a respectable way of raising the question of whether Obama is one of us." Maybe, but I think there are deeper anxieties at work. I even see an interesting symmetry between the discourse on both sides of the Atlantic. Here, if you criticize aspects of the US system, you are denying American exceptionalism and must wish you lived in France. Over there, if you suggest trimming welfare benefits or liberalizing markets, you have fallen prey to neoliberalism, the "Washington consensus," and rapacious Anglo-Saxon values.

From a global, trans-historical perspective, the nations of Europe, North America, and the Pacific rim are quite similar. We all have mixed economies, democracies with technocratic institutions, similar parties, similar corporations, open flows of capital, and substantial flows of people. One could illustrate the similarities with a raft of statistics. For example, the income tax rate for an individual who has the mean national income and no child in France: 13.1%. In the USA: 16.5%. Total federal revenue as percent of GDP in Germany: 11.5%. In the USA: 10.9%. Total expenditure on welfare as percent of GDP in Canada: 16.9%. In the USA: 16.2%.

To be sure, there are also large differences on particular measures between particular countries. I have cherry-picked numbers that are similar. But the overall point is valid: we have fundamentally similar systems, compared to the vast diversity found in the world today or in history.

But within each of the wealthy, democratic, OECD countries, we are anxious: anxious that we may be overtaken by China, that our consumption is unsustainable, that we cannot afford the entitlements we have today, that we are losing our edge. The mainstream parties within each OECD country (including the US) do not differ from each other by nearly as much as their rhetoric suggests. They all have the same anxieties and similar proposals. For instance, Democrats and Republicans both believe in a mixed economy with a federal welfare state, and the proportion of GNP that they would dedicate to the federal government (if they didn't have to negotiate with each other) would differ by just a few percentage points.

But the EU countries lie to the left of the Democrats in the US; and the US lies to the right of the center-right parties in Europe. Thus the rhetoric plays out as follows. If you're an American liberal, you can score effective debating points by noting failures of our current system. For instance, we spend more on public health care than the other OECD countries, yet we only cover a small slice of our population with Medicare, Medicaid, and VA benefits, whereas the European countries cover everyone for less. A tempting counter for conservatives is to accuse liberals of preferring Europe and not being part of our patriotic team.

Meanwhile, if you're a European of the center-right, you can score valid points by noting that their social welfare states are unaffordable (because of an aging population) and their labor markets are sclerotic. A tempting counter for European social democrats is to accuse the center-right of preferring America and the Washington Consensus.

I don't suggest this comparison in order to excuse those American conservatives who view President Obama as unpatriotic. Their position is infuriating, especially given the similarities between his policies and rhetoric and theirs. I think the effort to squelch criticism and to prevent borrowing from overseas is potentially catastrophic for our national competitiveness and progress. Yet I suspect its causes are deep and pervasive.

*"Tonight, we gather to affirm the greatness of our nation not because of the height of our skyscrapers, or the power of our military, or the size of our economy; our pride is based on a very simple premise, summed up in a declaration made over 200 years ago. 'We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their creator with certain inalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.' That is the true genius of America."

Posted by peterlevine at 10:43 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 24, 2010

in the debate about the civic purpose of education

My blog entry entitled "Should we teach patriotism?" will be anthologized in a book series called Current Controversies (Greenhaven, 2011). And Elizabeth Kish and J. Peter Euben discuss my blog entry entitled "Stanley Fish vs. civic education" in their chapter in Debating Moral Education: Rethinking the Role of the Modern University (Duke, 2010), pp, 78-70. I didn't anticipate or seek these uses of my blog, but I'm pleased that posts I'd long forgotten still have some life.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:14 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 23, 2010

what to do about an unwise public

The following appeared first on the Huffington Post.

On the American Prospect blog, Jamelle Bouie cites the latest Pew survey of public knowledge (only 38% of Americans can identify the incoming House Speaker; only 14% know what the inflation rate is) and concludes, "If there's a pundit trick that annoys me the most, it's the tendency to attribute particular ideological views to the public at large. In reality, the public doesn't actually know very much and isn't particularly ideological." Her His advice for politicians: "The best anyone can do is to meet the needs of your constituents, work on economic growth, and maintain good relationships with party leaders and activists. In the end, it's probably not a good idea to try to divine the 'wisdom of the people; from an election outcome, because by and large, the people don't have much wisdom."

But what happens if politicians don't try to meet the real needs of their constituents and don't take steps that will actually promote economic growth or other goods, such as security, freedom, sustainability, and equity? According to Joseph Schumpeter and kindred thinkers, that won't be a problem because the voters can judge overall success in periodical elections. They need not master specifics; they must simply assess their own circumstances and fire the incumbents if things go badly. Then the incumbents will be motivated to do a good job and can ignore citizens' advice about how to go about it.

This is not a crazy theory, and it rests on the valid premise that Bouie cites: "most people aren't terribly interested in public affairs or the minutiae of politics and come to their views by way of partisan affiliation and broad heuristics about the world." But clearly our Constitution is not designed for Schumpeterian politics. Division of power, staggered elections, bicameral legislatures, judicial review, and federalism all dilute and check the power of any particular incumbents and make it impossible to remove the people responsible for poor performance--unless voters are well informed about "the minutiae of politics." For example, in the last election, voters probably fired the Democratic majority because unemployment was stubbornly high. That was a smart and helpful move if the Democratic congressional majority was responsible for high unemployment. I think not, but I could be wrong. The important point is that our system makes it foolish to vote on overall performance.

So we need people to know enough to be wise.Some candidates for what we should know or understand as citizens include: the Constitution, statistics, the carbon cycle, the Holocaust, the positions of powerful politicians, the chief principles of Islam, the biography of Abraham Lincoln, macroeconomics, the Atlantic Slave Trade, accounting principles, the geography of Afghanistan, the contents of the recent health care reform, the major components of the federal, state, and local budgets, evolutionary biology, the tenets of classical liberalism and civic republicanism, Spanish, what causes AIDS, the rudiments of criminal procedure, important interest groups, the mechanics of voting, Keynes versus Hayek, Brown v. the Board of Education, how a bill becomes a law, the King James Version, our rights, the fact that half the world's population lives on less than $2/day, Letter from Birmingham Jail, and how to moderate a meeting.

That's a long list that could be much lengthened. I think we all need to avoid the kind of argument that runs: "People are ignorant of the things I know. That's why I vote right and they vote wrong." Liberals are deeply invested in that argument right now, and the relevant evidence is the public's ignorance of climate science, the composition of the federal budget, and the actual contents of the recent health care reform. But conservatives can play the same game with equal sincerity. For instance, the Intercollegiate Studies Institute regularly surveys college students and finds (to their way of thinking) woefully low levels of knowledge of the following issues on elite campuses: why capitalism allocates resources efficiently; what Plato, Aristotle, and Aquinas thought about natural rights; how the Soviet Union dominated other nations; and the origin of the notion of separation of church and state.

I'd like to change the subject. Our system does require public knowledge and virtue. Schools should teach all of the topics mentioned above, along with civic values. There is room for improvement in public education, but we cannot expect everyone to learn and permanently retain the entire corpus of modern knowledge. My own understanding is profoundly limited.

Thus we must identify the most important knowledge and find ways to teach it that go beyond schools. We need "lifelong learning." Although I respect many other kinds of knowledge, I most want citizens to possess a set of considered judgments about how public institutions should run. People can and should disagree about that question, but everyone's judgments should be based on informed and reflective thoughts about how to balance equity, participation, minority rights, and efficiency; how much to reward innovation and hard work versus protecting people against failure; when to preserve traditions and when to innovate; how much to demand of individuals and when to leave them alone; and how to relate to newcomers and outsiders. They should also know how to participate in constructive debates about such issues when people disagree.

To some extent, those matters can be discussed in classrooms and informed by readings. But much of our learning is experiential. From Jefferson's idea of a ward system to Tocqueville's observation that juries and associations were schools of government to John Dewey's notion of democracy as a set of learning opportunities, our wisest thinkers have always understood that the American system depends on knowledge and virtue that must be learned through experience.

Unfortunately, we have lost several of the most important venues for civic learning.

- Because of the consolidation of school boards, water boards, and other local governmental bodies and the replacement of citizen boards with expert managers, opportunities to serve on such bodies have fallen by about 75% since the mid-1900s.

- Because of the collapse of traditional civil society, the proportion of Americans who said they had attended a local meeting fell smoothly from about 65% in 1976 to about 35% in 2005.

- Because of the standards and accountability movement, citizens' participation in debates about schooling have become increasingly marginal.

- Because of the mobility of capital, local governments are no longer able to make their own decisions about how to balance the interests of businesses against those of the community. Business that don't get what they want can simply leave.

- For reasons that I don't fully understand, the proportion of children who participate in extracurricular groups has fallen.

Empowered associations, boards, meetings, and community debates are schools for democracy, and we are in serious danger of losing them. That's a very different complaint from "the public is unwise," and it suggests very different responses.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:49 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 22, 2010

the Coburn anti-earmarking amendment

Senator Tom Coburn (R-OK) plans to introduce an amendment this week to ban all earmarks in fiscal years 2011-13. Apparently, the amendment has a decent chance of passing.

The Coburn amendment is not a powerful tool for budget-cutting, even assuming that spending cuts are desirable in the short term. Earmarks in total represent about 0.3% of federal spending, and they direct the government to allocate funds to certain purposes instead of others. In other words, if they were banned, spending would not decline, even by 0.3%. That amount of spending would simply move from some programs to other ones.

Fiscal conservatives make subtler arguments that link earmarks to the rate of overall spending. One argument holds that congressional leaders bribe members into voting for big budgets by giving them earmarks. Conceivably--but by the same token, Speaker Boehner could use earmarks as incentives for members to cut the overall budget. It all depends on the priorities of the leadership.

A second argument holds that members vote for big federal budgets because then there is plenty of room for their pet projects. I don't see the logic of that. You can consistently vote to cut the federal budget and support an earmark that would allocate one millionth of the whole sum to your favored project.

The ability to add earmarks does allow Members of Congress to direct spending to their own districts in ways that may waste public resources and that help to buy them reelection. That's a problem, as is the fact that earmarks flow to districts with senior members (not to the places where the most important projects are).

On the other hand, a lot of earmarks are not actually projects located in the sponsors' own districts. For example, among the educational programs that have earmarks are Teach for America, the National Writing Project, National History Day, and Reading Is Fundamental. These programs are supported by large numbers of legislators. Their work is distributed nationally and they don't especially benefit any particular districts, but the co-sponsoring legislators are convinced of the programs' merits.

So the question becomes: Who should decide what is meritorious--Congress or the executive branch? There is an argument in favor of the legislature, an elected, accountable, deliberative body. The Constitution (article 1, section 1) vests "all legislative powers" in Congress, and arguably deciding to invest in Reading is Fundamental or National History Day is a legislative act.

On the other hand, when Congress earmarks money for a particular program, the executive branch agency that disburses the funds loses its ability to select the best organization through a competitive RFP process, and it loses its leverage over the recipient once the grant is made. The important assessment is conducted by legislators and their staff, not by specialists in the appropriate agencies. In occasional interactions with congressional staff, I have found them formidably smart and dedicated, but they cannot evaluate competing bids or evaluate programs, especially small ones. Thus the same earmarked programs tend to receive funds, year in and year out.

In sum, I think the Coburn amendment would do significant collateral damage by knocking out a bunch of small programs that Congress has wisely decided to fund and that the administration will not be authorized to fund. I fear that Congress won't repair the damage by permitting federal agencies to spend the money for similar purposes.

That is not to say that the earmark process is by any means ideal. For several of the educational programs I know about (at both the k-12 and college levels), a competitive grant program would work better than a congressional earmark for a named program. But an earmark is better than nothing in a considerable number of cases. Congress should be able to decide what to fund directly and when to delegate that power, and we should hold Members accountable for those decisions.

Posted by peterlevine at 2:07 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 19, 2010

The Wedding of Peleus and Thetis

The first 21 lines of Catullus' Song 64, in my translation:

Sprouted at the peak of Mt. Pelion,

the pines, they say, pushed right through Neptune's waves

to the surf at Phasis, Aeëtes' realm,

when the hand-picked force, those young oaks of Greece,

wanting to snatch from Colchis the Golden Fleece,

risked riding the salty waves on a ship,

and brushed the sky-blue sea with fir-wood oars.

Athena, who protects their citadel,

invented their light flying vehicle,

weaving the pine boards into one curved keel.

This ship was a first for the sea goddess.

When with its prow it plowed her wind-blown swell,

and its oar strokes sprayed white spume on her waves,

a face arose from the froth-covered strait,

a miracle the sea nymphs marveled at.

This one and many others they beheld,

the mortals, staring in the ocean sun:

nymphs rising out, naked, breasts in the foam.

Then Peleus was on fire for the nymph Thetis.

Then Thetis was not above a human match.

Then even father Jupiter knew it:

she was meant to be wife for Peleus.

(The whole long poem is well translated by Thomas Banks. The Latin I used is here.)

Posted by peterlevine at 7:57 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 18, 2010

guest post by Hank Topper: Next Steps for Rebuilding Democracy

Hank Topper lives in Santa Rosa, California where he has been helping to organize a broad city-wide effort to strengthen neighborhoods and improve the partnership between neighborhoods and city government. Hank is also a part of a small national group that meets regularly to share ideas on the work to rebuild local democracies. Before moving to Santa Rosa, Hank worked for the Environmental Protection Agency where he helped to design and lead the CARE program, EPA’s model community-based initiative. I have written about CARE before on this blog. The following post is by Hank.

It may be a good time for us, the various and diverse individuals and organizations working consciously in some way to strengthen democracy, to rethink our message and our strategy. The far reaching events of the last two years warrant this reexamination. The following are some thoughts to contribute to this reexamination. Let’s start with the first years of the Obama administration and their meaning for our work. It is, unfortunately, safe to say that our politics are in more disarray than two years ago. Not only are dissatisfaction and even despair more widespread, but we also now have a Tea Party movement making gains in directing this despair in ways fundamentally harmful to democracy. While the Obama administration may not be primarily responsible for these developments, it is, none the less, getting a large share of the blame. And, Obama, I would argue, is responsible for some of this the disappointment. He has, to date, failed to articulate either a clear picture of a “new politics” or a clear path we can to take to move towards changing our politics. With the bright promise of the new politics unfulfilled, many are left now to view Obama’s articulation of this hope as only another political trick.

Obama seems to be modeling his presidency on FDR’s government “for the people”, not on the strengthening of a democracy “by the people”. As a result, his practice has too often looked more like “politics as usual” than a new politics. The health care initiative was a classic example of this. Obama chose a Washington centered approach designed to get quick passage of health care reform. While this approach did not include the nation in this discussion, it did include the normal behind the scenes deals with special interests. This left the nation confused and the administration vulnerable to charges that the reform was just another power grab of big government. This appears to be a classic choice of short term over long term gains –politics as is over politics as it could be. There is no doubt that these are extremely difficult times and finding a way to address pressing immediate needs and work on deeper long term change could not be more challenging. So we can only say that Obama has not succeeded in finding a balance that could do this, and that, despite his intentions, the result of the administration’s work to date has resulted in some short term gains at the expense of long term progress in the creation of a new politics.

These developments have important implications for our work on democracy. We need, I think, to speak directly to the national frustration and disappointment with Washington and acknowledge the Obama administration’s failure to meet the expectations for a new politics. We need, more than ever, to articulate the democratic alternative to the dysfunction of our politics and present clear plans for how to create the new politics that we need. Our inability to present a clear democratic alternative means that the huge forces for reform working in our nation, unlike the anti-democratic forces that have developed into a political movement, have not been able to find an effective expression in our politics.

We also need to use the experience of the past two years to bring home the harsh reality that we cannot rely on our national political leaders to lead or even move us towards the new politics we need. The current political culture of our nation makes it extremely difficult for our political leaders, despite their best intentions, to talk about the fundamental changes we need. The lesson for all of us is that we need to stop looking to Washington and to the current political parties to take the lead on rebuilding democracy and take seriously the need for us to build a bottom up movement for democracy. We have spent too much time trying to get Washington to fund and support the work of rebuilding democracy. Let’s let the experience with Obama finally convince us to redirect our efforts to a more realistic strategy of bottom up democracy.

But just as important as addressing the disappointment with the Obama administration, we need to learn how to promote democracy in the context of our severe economic recession. We need to find a way to get people, as they may be doing in the UK, to see this as an opportunity to rebuild local democracy. We can use the failure of our national politics to deal effectively with the crisis as another illustration of the need for a new politics that can build a consensus and make decisions, but we can also use the economic crisis to make the need to rebuild our democratic communities perfectly clear. Governments have reached the limits of their ability to deal with this crisis. We need broad citizen efforts in every community to provide the support we need to get through these difficult times. This recession is a perfect illustration of the need for citizen initiative and the reality that governments can’t solve our problems for us. But we need to do more than use the crisis to talk about what is missing; we need to show in practice how our local democracies can meet this challenge. If we don’t do this, our work to rebuild democracy will become an irrelevant sideshow. Where have local organizations of citizens mobilized to address the challenges of the recession? Wouldn’t it be great if some local towns, cities, and neighborhoods took the lead in this, demonstrating the capacity of citizens to take responsibility for dealing with the recession instead of just relying on state and federal governments to address our needs? This, like the 9/11 attack, is our opportunity to not just talk about how a democracy would handle this but to show it in practice.

In addition to addressing the effects of the recession, our nation is also engaged in a very important conversation about the importance of rebuilding our economy along more sustainable lines. This, again, is a conversation that we need to engage in to raise the fundamental question of the role of citizens in this effort to restructure our economy. Can we create a sustainable economy with government centered technological fixes, which is again the disappointing approach of the Obama administration, or are finding better ways to engage citizens and rebuilding our democracy the key to building a sustainable economy? We need to take the national conversation on how to rebuild our economy as an opportunity to ask the question: What exactly does the “community” part of sustainable communities look like? There is a very large and growing local and “off the grid” movement already underway looking for answers to this question. We have the opportunity to link this sustainable community movement to democracy and help to ensure that sustainable communities are democratic communities.

Getting democracy on the agenda of our national discussion also means trying to shift from our focus on fixing the economy to a much broader discussion of the sources of our current crisis. What makes this crisis so difficult for our nation is the combination of the economic and political crises –a perfect storm building on all of our weaknesses. Perhaps an effective way we can use to get across the central role that the decline in our democracy plays in this might be to talk about the fact that is not just an economic bubble that has created the crisis that we face. We have had a deeper and even longer lasting bubble in our politics as well. Our “political bubble” –call it our bubble of trust in expertise-- has resulted from our unrealistic belief that we could turn over responsibility to professionals --scientists, government experts, corporate managers-- and let them handle things for us as though they alone had the knowledge needed to run our complex world. We have been talked, just as we were talked into cheap mortgages, into giving up our own democratic power and responsibility to governments, experts, corporations. This “political bubble” of over confidence in experts has gone on much longer than the economic bubble. It has been a long and gradual process beginning at the start of the last century of turning over our responsibility to government experts (government will take care of our problems) and to corporations (the market will satisfy our needs). This bubble of overconfidence in experts has resulted in the erosion of our democracy and the rise of governments and corporations that dominate us rather than serve us. And, just as we should not be surprised at the results of our overconfidence in financial institutions, we should not be surprised at the results of the power that our overconfidence has given to experts. We forgot that power corrupts and would turn experts into special interests and that their interest in power would make it impossible for them to work together. So, the deep anger in our nation is not only a result of the failure of this class of professionals created by our overconfidence in expertise, it is also anger over the loss of democracy, the loss of a real voice for the average citizen, the loss of real conversations, listening, and respect for each other that characterizes a democracy. The Tea Party movement and its attack on government is succeeding in capturing the anger and frustration that we feel, but their attack on government makes no distinction between the government of experts and the democratic government, so it undermines both. Explaining the “political bubble” and the loss of our democracy would give us a chance to pose our positive plan to rebuild democracy to the negative Tea Party plan of attacking government.

As a nation, we are faced with some very difficult challenges. We will be in the best position to meet these challenges if we can all see them as an opportunity to do something meaningful and exciting –to rebuild and, in the process, create something better. Meeting our challenges will not be easy and it would also help us all to start talking about the need for a decade of rebuilding. The best way for us to get across our message about the need to rebuild our democracy may be to place it the context of this larger and exciting challenge to rebuild our nation. Discussing the work of rebuilding democracy in the context of an overall decade of rebuilding will help us make the connections we need to the forces that are already engaged in this work. We can describe the rebuilding effort as a three legged stool: one leg for the work to rebuild our economy, reduce our debt, learn to live within our means, and rebuild the infrastructure and education we need to be productive; the second leg for the work to build a sustainable world, to rebuild our economy and communities that can live within the means of the planet; and the third leg of our decade for rebuilding will focus on rebuilding our democracy to create a politics that will bring back our ability to find common ground and make hard decisions, that will reclaim our politics from experts and elites and return responsibility and power to citizens. We can explain that this third leg of our rebuilding effort will ensure that the sustainable economy and communities that we rebuild will be communities based on our deepest values of respect for each person and faith in the ability of democracy to tap into the vast resources of our people. We can also explain that rebuilding our democratic communities and reengaging citizens will be essential to meeting our needs in these difficult times of budget deficits and limited resources for government. Our message: We are now at the beginning of a decade of rebuilding. The work to rebuild our democracy has to be a key part of the work so that we have strong communities to provide the support we need in this recession and so that we can reclaim the central role of citizens in our politics and create the kind of world we are looking for. Defining this as our challenge can turn this decade of rebuilding into an exciting opportunity to create a better world.

But the work to craft our message for the current situation, important as it is, probably is not where we need to focus most of our energies. The reality is that our message about democracy, no matter how well we state it, is currently reaching a very limited audience. I think that this is primarily because most people do not have any practical experience with democracy. Without this experience the average citizen still finds the talk about democracy both unrealistic and abstract. Citizens need experiences that demonstrate the possibility of a different kind of politics to be able to counter the despair and cynicism that have resulted from our current politics. So even more important than finding effective ways to talk about democracy, we have to find ways to help citizens recreate the experience of democracy.

The best place to do this, I would argue, is at the local level. In a democratic federal system with separate layers of government, people at the local level have just enough independence to have real power and to practice real democracy. That is our advantage and the weak spot of the national power structures that dominate our current politics. That is why there is a vast movement of organizations focused on “going local” and going “off the grid.” So it is possible, despite the dysfunction of national politics, to create at the local level the democratic experiences and practice that people need to understand the possibility of an alternative to our current politics. On the ground in local communities is the place where we can show the relevance of democracy in practice to the work to build strong and sustainable communities and to address the recession. So I would argue that our top priority now is to mobilize our limited resources to help rebuild our local democracies. There are many great examples of positive local democratic initiatives across the country. These initiatives include both the collaborative work that brings people together in a democratic approach to solving problems as well as the broader community building efforts working to strengthen neighborhoods and reform local governments so that they reorient their work to support citizen engagement. This is the kind of work that we need to expand to build the basis in experience for the broader national effort to transform our politics.

What would that mean for our loose federation of forces working on democracy? It would mean putting more of our resources into building democracy in real places --in cities, towns, and neighborhoods. In those places where there are existing efforts to strengthen local democracy, it would mean joining in and becoming full partners in these ongoing efforts to advance this work. Where an existing effort to strengthen local democracy has not begun, it would mean joining with local groups to get one started. Can we collectively find the resources and people, maybe just 10% of our organizational resources, to make a real contribution to the efforts to rebuild democracy in 50 towns and cities? That could be the critical mass we are looking for. That is the kind of work that would, among other things, make it possible in the future for someone like Obama to talk about rebuilding democracy.

How might we go about working at the local level to build democracy and what do we have to offer in this work? Lessons learned in the work on local democracy, make it clear that we need to go into local work respecting the very broad and varied efforts to create change that already exist in every town and city, learn from them, and talk about the relevance of rebuilding democracy to the goals of all the organizations and individuals working to address local concerns. It is in these conversations that we will learn how to make democracy relevant to the leaders working in our cities and towns –the go local, sustainable living, social justice, public health, environmental justice, neighborhood leaders, community builders, youth groups, block watches, government reformers, local business and development leaders, smart growth organizations, etc. Experience shows that if we are willing to learn from and respect the work of these groups and individuals, it is possible to work with them to form a broad coalition focused on rebuilding local democracy. Everyone can understand that engaged citizens with strong and organized neighborhoods working with a local government that sees its role as partnering with neighborhoods and promoting civic engagement is the foundation we need to create a strong, sustainable and healthy cities and towns. Working together to create this kind of democracy in a town or city creates the experience that we need to see that there is different and non-partisan politics that can get us beyond the divisions and the gridlock of our current politics. We can help build the broad coalitions that will do this work to strengthen local democracy and demonstrate that it is possible to create an alternative to our current politics. This is exciting work. None of our cities have really put all the elements of a strong democracy together, so we all have a lot to learn and a lot of exciting work to do. It is this work at the local level, not the national level that has the best potential to create the model we need to transform our national politics.

And, while we should not underestimate the patient work that will be needed to build on or create the ties and trust we need to do this work, neither should we underestimate the contribution that we can make to this work. Our ability to help name the problems we are facing in our politics as a lack of democracy will help link the work of local leaders to the deep and empowering democratic traditions of our nation. This is a real source of strength and inspiration that can be invaluable to the ongoing local work. We also can provide links to the practice and lessons learned in cities and towns across the nation that have been engaged in rebuilding democracy for the past twenty or more years. These links are both invaluable and inspiring. Just realizing that others have tried this work and succeeded and that others around the world are working at the same task can be extremely helpful. We can also work to facilitate communication among communities working to rebuild democracy so that they can learn from each other. And, finally, we can bring a toolbox of skills and techniques that have developed to help make democracy work including organizing skills, deliberative approaches and techniques, facilitation, conflict resolution, collaboration skills, and others. All this means that we have a real contribution to make to the efforts to strengthen local democracy.

Are we prepared to take up this task? Our work over the last couple of years, if I am correct, has not changed significantly to meet the crisis we face. We are still fragmented and stove piped –still each using narrow definitions of democracy. And, we are still too focused on influencing Washington. We are doing good work but in relatively narrow areas: in civic education, deliberative forums, collaborations, dialogues, partnerships, etc. But these are all pieces of what would make up a practicing democracy and we rarely put them together to demonstrate what democracy would look like in full. It is in the context of rebuilding local democracy that all our ideas and approaches can be put to use as a part of a rebuilding effort. It may actually be in the work to rebuild local democracies that we can best break down our stove pipes and learn how to coordinate our work. The work to rebuild local democracies could give us the focus to pool our resources so that together we can make real progress. Once we ask the question “how can we work in this place to help rebuild democracy” that we will begin to look for and work with all the different democratic resources that can help. But we will have to enter into this work as representatives of all the democratic resources and not just as representatives of the particular goals of our organizations. Can we do this? Can we get our organizations to free up individuals to work in places to help with rebuilding democracy? Is there another way for us to bring our democratic resources to help communities rebuild their democracies? Our schools, colleges, and universities, especially those with the most ties to the local community, may be in the best position to take up this work to join in the work to rebuild our local democracies. Can we help to direct the civic engagement programs of these schools away from service oriented volunteering to the work to build the capacity of neighborhoods and local democracy?

There may be a lot of unanswered questions about our capacity to do this work. But there is no question about the opportunity that we have. There is a vast energy at the local level, especially among our youth, to rebuild our communities and our politics. We have the opportunity to make a real contribution to this work by joining in and demonstrating in practice that the work to rebuild democracy is the key to creating the community and politics that we all are searching for. So our slogan for the next years: Get organized, go local.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:41 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 17, 2010

a community economic development primer

(This post is meant to resemble my primer on relational community organizing; I plan to write others on community service, practical deliberation work, etc.)

Many thousands of not-for-profit institutions are involved in various forms of economic development in the communities where they are located. For example, some use federal Community Development Block Grants and other funds to develop low-income housing. Sometimes they can plow the proceeds from their investments into further development. They solicit public participation in their decisions, both as a matter of ethical commitment and in order to comply with funders’ rules. Hence these institutions belong in the fields of community organizing and public deliberation; but their emphasis on managing tangible assets makes them different. They contribute to civic renewal by promoting democratic deliberation, magnifying the voice of poor people, building civic skills--and creating assets that are subject to democratic control because they cannot be moved.

In 2005, there were 4,600 community development corporations (CDCs) in the United States, employing nearly 200,000 people, building about 86,000 residential units annually, and managing commercial property and spawning other enterprises.

The concept of a CDC is not defined in federal law, and in practice, CDC’s resemble other non-profit organizations that have similar missions. For example, a community development bank specializes in lending rather than developing property, but those two roles overlap. Like CDC’s, community development financial institutions (such as banks and credit unions) are widespread and influential, holding more than $25 billion in assets in 2007.

Churches may also build, lease, finance, or sell homes and other buildings for the good of their communities. Sometimes they create spinoffs formally known as CDCs, but often they handle the financing directly. A famous example is the Greater Allen African Methodist Episcopal Cathedral in Queens, New York, which manages assets worth over $100 million, including rental properties, businesses, and a school.

Meanwhile, community land trusts tend to purchase open space for preservation, but some urban land trusts operate much like CDCs, and some CDCs buy land to preserve or create open space. Community organizing groups such as the Industrial Areas Foundation have created CDCs; and some CDCs have affiliated with community organizing networks.

In the city where I write this post, the Somerville Community Corporation is a not-for-profit real estate developer that invests its profits in new development, a provider of adult education, an emergency lender to low-income renters, a community organizing group affiliated with the Industrial Areas Foundation, a convener of public deliberations about matters like planning and municipal budgeting, and a lobby on behalf of employment, transportation, and welfare programs. This combination of functions is typical, and as a result the Somerville Community Corporation could be listed under several categories of civic work--as could the Allen Cathedral or the Industrial Areas Foundation itself.

Regardless of their precise status, all these institutions are anchored legally in their physical communities. They manage assets that have market value and they use business techniques (such as charging fees for services and lending money with interest), but they are not permitted to move. Their structure honors the civic virtue of loyalty and gives them a practical need to employ “voice” rather than “exit” to address problems. How they exercise “voice” varies, but extremely common are public meetings, boards that represent local residents, and public events designed to solicit public input. Meanwhile, all these organizations express—at least in theory—an ethic of trusteeship and public service. That ethic is usually codified in the organization’s nonprofit status and by-laws, but there is no reason that a for-profit business cannot serve the same purposes if it is anchored in a community and accountable to residents.

CDC’s have roots in Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty, and specifically the thousands of Community Action Agencies (CAA’s) that were created under federal law and asked to oversee local federal welfare programs, including Head Start, Legal Services, and public housing. The Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 had required that all new federal welfare programs be “developed, conducted, and administered with the maximum feasible participation of the residents of the areas and the members of the groups served.” CAA’s arose to meet that need.

They still exist; more than one thousand belong to the Community Action Partnership, and many of those are also classified as CDC’s. But the typical mechanisms for encouraging the participation of residents have evolved. In the 1960s, it was common to hold public elections for board members. This was problematic because the United States was already covered by a smooth tessellation of local governments with their own elected leaders. Adding a new layer with different boundaries caused constant jurisdictional conflicts and struggles for power. CAAs were supposed to avoid patronage and corruption, but often turnout was poor, and elections offered opportunities for corruption. Today it is much more common for a community-based development organization to be structured as a private, not-for-profit corporation that has a board with fiduciary obligations to the public. Some or all members may be elected, but some may be representatives of local institutions, including municipal governments. Foundations and governments also exercise considerable power by deciding what to fund. CDC’s and kindred organizations do not claim the kind of democratic mandate that comes from public elections, but they do welcome and promote participation.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:11 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 16, 2010

civic agency

Based on blog reports by Cecilia Orphan and Harry Boyte, it sounds as if the recent Civic Agency meeting in Washington was excellent. It was organized by the American Democracy Project of the American Association of State Colleges & Universities (AASCU) along with the Center for Democracy and Citizenship. The AASCU has a valuable grassroots base in the form of its member campuses, which mostly serve first-generation college students. Other participants in the meeting included: "Rock the Vote, Sojourners, the White House Office of Social Innovation, community colleges, the American Library Association, National Issues Forums and Strengthening our Nation’s Democracy network."

Boyte summarizes three key themes:

1. "A focus on the empowerment gap needs to replace the achievement gap. ... [The] deepest problem in our education is that young people – especially children and teens of low income, minority, and immigrant backgrounds – feel “acted upon,” not agents of their education."

2. Public knowledge: people can create knowledge that is otherwise unavailable, by working together outside of specialized knowledge centers such as labs and academic departments.

3. "A new public narrative: We the People is not something in the future – it is emerging all over the place, as our colleagues, students, staff, and faculty rework relations with elected officials and other decision making bodies to be partners in public work, not mainly providers of services."

Posted by peterlevine at 11:03 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 15, 2010

contra Krugman

I find that I have written 17 blog posts critical of Paul Krugman since 2005. Since 2008, these posts have generally been defenses of Barack Obama. As I wrote in February 2009, "Krugman's critiques of Barack Obama ... represent one of the most interesting debates in American politics."

Today's Krugman column provides an opportunity to sum it up. This is the key paragraph:

- In retrospect, the roots of current Democratic despond go all the way back to the way Mr. Obama ran for president. Again and again, he defined America’s problem as one of process, not substance--we were in trouble not because we had been governed by people with the wrong ideas, but because partisan divisions and politics as usual had prevented men and women of good will from coming together to solve our problems. And he promised to transcend those partisan divisions.

During the campaign, Krugman wanted Obama to capitalize on the unpopularity of George W. Bush to make a sweeping and persuasive case to the American people: things had gone badly because of conservative ideas; liberal ideas were better. It was deeply frustrating to Krugman, Sean Wilentz, and many others (including some of my friends) that Barack Obama wouldn't say that forcefully and relentlessly. He did say much of it, but mixed with other themes that had no resonance for Paul Krugman. What Krugman heard was a call for "bipartisanship," which seemed exactly the opposite of what we needed. Bipartisanship meant blurring the distinctions between liberals and "people with the wrong ideas" and signaling an excessive willingness to compromise.

After the election, Krugman argues, Barack Obama should have explained and defended liberal policies, whether or not they could get through Congress. Above all, he should have "fought" for an "economic plan commensurate with the scale of the crisis." Krugman doesn't explain what "fighting" means for a president, but perhaps it means vigorously debating one's opponents in public forums. If, despite Obama's most vigorous ideological arguments, a huge stimulus package failed in Congress, the "people with the wrong ideas" would have to take the blame.

Instead, Krugman believes, the president compromised on his liberalism, and therefore Americans did not understand their options. Communication is everything for Krugman. From today's column: "What Mr. Obama should have said ... Mr. Obama could and should be hammering Republicans ...There were no catchy slogans, no clear statements of principle ... " The president "has the bully pulpit."

I don't believe that bipartisanship was the distinctive message of the Obama campaign; in fact, the candidate paid no more than the usual and customary homage to it. But Obama did reject the diagnosis that we were simply "in trouble ... because we had been governed by people with the wrong ideas." He didn't think that he could explain or argue the American people into a different political philosophy, one in which our major troubles stemmed from conservative ideas and the solutions lay in a more activist government. Obama wanted a more activist government and has taken the largest step in that direction since 1974 with the health care bill. But he didn't believe that the way to get there was to conduct a debate on ideology. He did think, contra Krugman, that the main problem was the process and not the misguided people in office.

After all, the number of "people with the wrong ideas" (as defined by Krugman) is very large. All Republican elected officials, plus the majority of American voters who supported that party in several recent elections, have the wrong ideas, from Krugman's perspective. So do at least one third of elected Democrats and a large proportion of Democratic voters. So do all the leaders of major foreign economies, who are asking Obama to lower deficits and not spend. So do many impressive economists. I personally find Krugman's economics quite persuasive, but the task of explanation and persuasion is much harder than he realizes.

People begin with a very deep distrust of the federal government. Because of that distrust, just six percent of Americans believed that the $787 billion stimulus package had created even one job a full year after it passed Congress. I suppose Krugman would say that the stimulus was too small to be noticeable. But the kind of stimulus he wanted was certainly too big to pass Congress, so Obama could only have won the debate, not the policies he needed. In any case, if you live in a country where 94% of people believe that almost one trillion dollars of their money bought no jobs, you have a deeper problem than being "governed by people with the wrong ideas." You need to diagnose why most people are so deeply distrustful and skeptical.

One reason is a natural and healthy distrust of a large and distant federal government. No other diverse, continental-sized country has a central government that has addressed national problems and won broad popular support. The European democracies are far smaller; Russia, India, and China have worse governance problems than we do. Governing from Washington is a tough task.

A second reason is poor results. We devote large amounts of our income to taxes, but because of military spending, wasteful health spending, and misconceived programs like the Farm Bill and the mortgage income deduction, we don't get very good value for our money.

A third reason is distaste for political leaders who appear to squabble and score points rather than cooperate to solve our problems. Krugman wants Democrats to pin the blame for bad policy and obstructionism on Republicans. But Americans hear the counter-charges as well as the charges and decide that they don't want to entrust large amounts of their money to any of these people.

A fourth reason is exclusion from public life. For a generation, we have been replacing democratic participation in public institutions (like schools) with technocratic governance: with efficiency measures, accountability systems, and other tools that ordinary people cannot control.

A fifth reason is "the Big Sort"--our mass migration to enclaves (whether neighborhoods, news sources, or organizations and associations) where we only encounter others who agree with us. The Big Sort lowers trust in government because individuals believe that most other people agree with them, yet the government acts contrary to their values. They underestimate the degree to which we actually disagree with one other. Our opponents, meanwhile, become shadowy enemies motivated by terrible values, instead of flesh-and-blood neighbors with different life experiences.

A sixth reason is the collapse of powerful intermediary organizations, associations with grassroots chapters and national lobbies that once connected people to the policy process. Those associations included fraternal and ethnic clubs, unions, and churches (of which only the evangelical conservative ones remain strong). They gave people a feeling of ownership by multiplying their power.

And a final reason is a terrible process. As long as elections are privately funded, districts are gerrymandered, and legislative procedures are rigged, it doesn't matter who makes what argument or what the people believe who govern us. Policy will be determined by power.

Obama explicitly understood these points. He concluded that the problem was the process. Debate wouldn't solve anything, but we needed to build new relationships--relationships of trust between citizens and the government and among diverse citizens. Krugman scoffs at the idea of "men and women of good will ... coming together to solve our problems." That is indeed too much to expect of Congress, but it happens regularly in civil society. At the national level, politicians can at least display more of the civility that Americans expect of fellow citizens. (Civility, by the way, is not the same as bipartisanship.)

I think Obama's diagnosis and promise were correct. That doesn't mean that the execution has been satisfactory. There have been no new policies that permit or encourage broad public participation. There have been no serious changes in the rules and processes of Washington. The administration has tried to negotiate its way to satisfactory policies and explain their merits to the American people, instead of changing the system itself. In that sense, they have been doing what Krugman recommends, but with less economic ambition and impact. We need the kind of transformational presidency that Barack Obama promised and that Paul Krugman considered a mistake.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:22 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 12, 2010

major media comment threads

Few forms of writing are as depressing as the comments posted on major newspaper and news channel websites. People are entitled to their opinions, but the degree of repetition, cliché, incivility, irrelevance, and incoherent rage in comment threads is discouraging. Notice, for example, how almost any article about a survey will attract vituperative comments accusing the pollster of fabricating data to help one political party.

I do see exceptions. For instance, somehow the Atlantic's Ta-Nahesi Coates maintains an active comment space in which people actually write interesting remarks that build on one another. But I have met reporters who won't look at the comments on their own articles, despite mandates from management to do so, because they are so tired of being called names regardless of what they write.

I don't know how many people even glance at such comment threads, nor what happens (if anything) when they do. But I worry that after reading comments, we start to think we live among people who aren't capable of reasonable conversation, and that depresses our interest in deliberation and democracy.

Some sites seem to restrict participation. For example, I think you need a New Republic subscription to comment on TNR (a barrier that prevented me from posting a civil but highly critical response to Sean Wilentz). Apparently, some sites use a combination of software and human labor to delete the really offensive stuff. But that leaves a lot of comments that, while they break no rules, add no value.

Is there a better way?

Posted by peterlevine at 12:52 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 11, 2010

media literacy and youth

Austin, TX: I am here for a Millennials and News Summit at the University of Texas, subtitled, "The Real Challenge to the Future of Journalism and Journalism Education." Meanwhile, back in DC, Temple University's Renee Hobbs released her Knight Commission White Paper on Digital and Media Literacy: A Plan of Action at an Aspen Institute event, to comments from FCC Commissioner Michael Hobbs, the head of the American Library Association, and many other luminaries. In her paper, Hobbs summarizes the challenges of using the modern media responsibly--and creatively--and she develops some specific proposals, such as "a national network of summer learning programs to integrate digital and media literacy into public charter schools," and a "Digital and Media Literacy (DML) Youth Corps to bring digital and media literacy to underserved communities and special populations via public libraries, museums and other community centers." The whole paper is an excellent primer to the subject we will be discussing in Austin today.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:07 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 10, 2010

Wilentz v. Ganz on the Obama social movement

During the 2008 presidential primary campaign, the Princeton historian Sean Wilentz was a strong backer of Hillary Clinton and critic of Barack Obama. He launched many debating points. For example, the Obama Campaign allegedly showed "indifference--and at times, even pride" about the fact that white working class voters were opposing Obama in the primary. Wilentz predicted "a Democratic disaster among working-class white voters in November should Obama be the nominee." Obama was supposedly the anti-political candidate, the heir of goo-goo reformers like Adlai Stevenson and Jimmy Carter, whereas Hilary Clinton, like Franklin Roosevelt, relished partisan combat and understood how to pass legislation. When she insisted on the importance of elected national leaders in the civil rights struggle, she was correct about history, and her critics were just playing the race card by claiming that the movement had achieved its victories at the grassroots.

And now Wilentz gets his chance to say, "I told you so." His recent New Republic piece is headlined, "Live By the Movement, Die By the Movement: Obama’s doomed theory of politics." "Clearly," he writes, "the hopes and dreams that propelled Obama to the White House are in disarray. The social movement politics that some of his most fervent followers ascribed to him--the idea of electing a 'post-partisan' president as the leader not of a nation or even of a political party but of a personalized social movement--has failed." Wilentz names Marshall Ganz as the source of this failed idea.

Of course, Ganz' diagnosis is the precise opposite. A moral social movement, rooted in Democratic Party cadres and angry about conservative abuses, swept Obama into office over the technocratic Hillary Clinton and the fake populists McCain and Palin. But after Inauguration Day, Obama "chose to demobilize the movement that elected him president. By shifting focus from a public ready to drive change--as in 'yes we can'--he shifted the focus to himself and attempted to negotiate change from the inside, as in 'yes I can.'" In other words, there was no progressive social movement when it really counted, and that is why the president couldn't make more headway on policy. President Obama actually governed the way Wilentz had hoped President Hillary Clinton would govern.

Wilentz writes:

- Fundamental to the social movement model is a conception of American political history in which movements, and not presidents, are the true instigators for change. Presidents are merely reactive. They are not the main protagonists. Obama himself endorsed this conception constantly on the campaign trail, and has repeated it often as president, proclaiming that 'real change comes from the bottom up.'

But this theory was only one theme during the campaign, and a deeply submerged theme in the administration so far. Much more prominent is the idea that Wilentz seems to endorse: Democratic presidents solve our problems by negotiating and implementing smart policies. As I observed months ago, the President's rhetoric has been subtly shifting from civic empowerment to a focus on his own personal leadership--from "we" to "I." Seeking the nomination in Iowa, Barack Obama said, "I hold no illusions that one man or woman can do this alone." More than two years later, responding to the Massachusetts Senate election, he said:

- So long as I have some breath in me, so long as I have the privilege of serving as your President, I will not stop fighting for you. I will take my lumps, but I won't stop fighting to bring back jobs here. (Applause.) I won't stop fighting for an economy where hard work is rewarded. I won't stop fighting to make sure there's accountability in our financial system. (Applause.) I'm not going to stop fighting until we have jobs for everybody.

Whether change comes from the grassroots up or from national leaders down is a worthy topic of debate. How the president should govern is certainly a worthy and difficult topic. But it's important to get clear on the factual basis of the debate. First, the "post-partisan" and "anti-political" themes, if they were present at all in the campaign, have nothing to do with the embrace of a social movement and bottom-up change. The social movement that elected Barack Obama was partisan, political, and ideological. Second, the campaign and the administration never embraced Marshall Ganz' strategies, except at the margins. Thus the Obama Administration's first two years are no test of Ganz' theory, which remains basically untried.

(I've never read Sean Wilentz' historical writings and would surely learn from them. But I've been watching his public interventions for a long time and marking them as an example of a certain kind of elitist liberalism that contributes, in my view, to the weakness of the left. During the impeachment hearings of Bill Clinton, he lectured House Republicans, predicting that "history will track you down and condemn you for your cravenness." I was certainly against the impeachment, but I don't think that professional historical expertise was particularly relevant to the decision, nor that Professor Wilentz could see into the future. To me his testimony rang of Ivy League disdain, an effort to make a particular moral worldview look like the only intelligent position. Ganz is certainly a moralist as well, but he respects and engages with the core moral commitments of other Americans.)

Posted by peterlevine at 8:10 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 9, 2010

how more young African American voters could have been engaged

According to new research released today by CIRCLE and the Generational Alliance, younger African Americans (ages 18-29) represented 14% of all younger voters, just about the same as their proportion of the whole young-adult population (14.4%). That means that young African Americans voted on par with other young adults, not a bad comparative showing when you consider that they face the challenges of lower average educational attainment and higher rates of disenfranchisement. On the other hand, keeping pace with other young Americans was not such a great result when the turnout of all 18-29s was only 21%. And younger African Americans lost a lead that they had previously held: they had the highest turnout rate among young people in 2008. If Black youth turnout had been higher in 2010, it would have been good news for Democrats (86% of young adult African Americans voted Democratic) and a source of political strength in the African American community.

Could anything have been done to raise the turnout rate? To start, politicians should not have taken it for granted. Biko Baker, one of the best young organizers in America and a member of CIRCLE's advisory board, offered to take a leave of absence from his nonpartisan work to help organize for the Democrats in urban Wisconsin. The party told him it wasn't necessary: "we truly think that people will be inspired to help the President during these next couple of weeks." But our own focus groups in Baltimore in 2008, plus the observations of real experts like Cathy Cohen (director of the Black Youth Project) found that young African Americans were never in love with Barack Obama. Even in 2008, they felt hope mixed with a great degree of skepticism. It was an open question whether they would be "inspired to help the President," and much would depend on what he did for them. In the end, turnout was low--not compared to other young people, but compared to what the Democrats needed to win.

To engage young African Americans, the administration could have explicitly addressed racial injustice and issues perceived as racially salient, such as sentencing disparities. Instead, as Cohen writes, a decision was made to "run away from race, and only respond to the issue of race when it was in crisis mode ..., leaving young people feeling alienated by the rhetoric and discourse around race in this country." I agree that the administration has been muted on racial issues--probably more so than other Democratic administrations would be--out of fear of reinforcing animus against the Black president. But I also think that the politics were tough. Explicit discussions of race would have alienated some white voters, and it would have been hard for the president to deliver more than rhetoric on issues like sentencing disparities.

A second strategy would have been to address the critical issues facing young African Americans. The September unemployment rate for African Americans between the ages of 16 and 24 was 32 percent (edging down to 29.7 percent in October). That is catastrophic. But I fear that our political system and climate gave the administration inadequate tools to respond.

The third strategy would have been to give young African Americans a voice and work to do on behalf of the causes that they care about. Many thousands were mobilized as active supporters of Barack Obama in 2008. When the election was over, they should have been maintained as part of an interracial social movement. It would have been illegal as well as unethical to use public funds or the White House to support that movement, but the millions of Obama donors could have been persuaded to fund grassroots work privately.

That would have meant hiring people like Biko Baker and giving him real authority. In turn, he advises integrating media and creative work into a youth movement. He cites as an example the Black Youth Project's “Democracy Remixed” Video Contest. Thus I'll end with my favorite video from that contest, by Chris Webb. I don't necessarily agree with Webb's whole message, which focuses relentlessly on culture change within the Black community. But I post his work because it exemplifies the excellence of young people's political voice.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:27 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 8, 2010

Millennials and News Summit

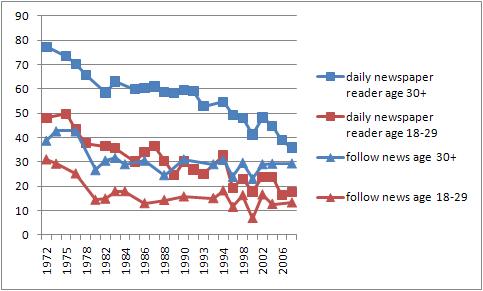

I will be going to Austin, TX later this week for a "Millennials and News" summit at University of Texas. I just made the following graph to orient my own thoughts:

It shows a severe decline in newspaper readership since the early 1970s. The decline is much less pronounced for young adults (ages 18-29): they started out lower but their elders have fallen to meet them. This trend is ground for concern because traditional newspaper readers had many civic virtues, being much more likely to engage in community affairs. I believe the reason for the decline is not a disappearance of civic virtue, but rapid changes in the news business.

The graph also shows a decline in following the news and public affairs "most of the time." As newspaper readership plummeted in the 2000s, following the news did not fall in tandem--because people were switching to new sources of news. But those new sources didn't solve our problem, because attention to the news remains lower than it was in the 1970s and 1980s. For youth, the "attention" rate has been pretty constant, despite rapid changes in the news environment, since 1980. It is also very low by any reasonable standard, with less than 15% regularly following the news.

Posted by peterlevine at 2:15 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 5, 2010

Tony Judt's Postwar

I just want to put in a plug for Tony Judt's book Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945, which I finished a few weeks ago. It's a sweeping, comprehensive essay about politics, economics, popular culture, high culture, diplomacy, and society in Europe from Ireland to Belarus, from 1945 to 2005. Judt provides no references and quotes relatively sparely, so the narration is uncluttered and un-academic; it moves along at an exhilarating pace. Judt long ago abandoned the grand theoretical frameworks of Marxism and Zionism that he held in his youth, and Postwar is a model of history as a set of concrete, particularistic, contingent episodes (one damn thing after another). Many of the trends in modern European history emrge as fairly accidental--political integration is the best example.

Judt is certainly not value-neutral; in fact, he is a firm moralist with humane and classically liberal judgments--and no tolerance for the deeply intolerant.

A few large conclusions surprised me. Mikhail Gorbachev emerges as a pivotal figure, whose discretionary choices as General Secretary sent Europe on one course when it could have gone in quite different directions. I don't think Judt subscribes to a Great Man Theory of History--no other individual in the book plays a similar role. But Judt does deny that the peaceful collapse of communism was inevitable, or that it was brought down by US policy or anti-Communist dissidents. He thinks Gorbachev took it down, which would make the former Soviet leader one of the great figures of all time.

The differences among European social welfare states emerged as more important than I had realized. The French nationalized major industries to control employment and wages (and then privatized once they had an officially Socialist government). The Scandinavians, on the other hand, never nationalized but taxed income and spent liberally on individual entitlements. The British government directly provided health care when the Germans and most other continentals relied on private delivery.

On the other hand, certain similarities between communist states and western democracies struck me. Judt is unsparing in his criticism of the purges, the environmental devastation, the human waste, and the general tyranny of communism. But the Warsaw Pact states operated in the same financial and commodities markets as the West and experienced some of the same ups and downs. They also experienced similar generational changes. They were governed until the sixties by old men who had been formed before World War One, and then changed when a new cohort of people took over whose formative experiences had been in the fifties.

Judt's wide scope takes in parts of Europe often ignored (by people like me), such as the southern Balkans, the eastern Slavic lands, Portugal, and southern Italy. Postwar is partly the story of amazingly rapid modernization, spreading from northwest Europe outward. A comparison to contemporary China seems appropriate.

Postwar ends with a thoughtful essay about what Europe is like today and where it seems to be headed. Judt is aware of the frailties of the European Union and the challenges of the present, including how to deal humanely and justly with immigration and how to serve the young appropriately when populations are predominantly old. Yet he sees tremendous potential in this huge zone of economically integrated democratic states. For all the talk of China (or India) as the great power of the next century, I would not be surprised if Old Europe actually dominates.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:30 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 4, 2010

against a cerebral view of citizenship

For a faculty seminar tomorrow, a group of us are reading Aristotle's Politics, Book III, which is a classic and very enlightening discussion of citizenship. Aristotle holds that the city is composed of citizens: they are it. Citizenship is not defined as residence in a place, nor does it mean the same thing in all political systems. Rather, it is an office, a set of rights and responsibilities. Who has what kind of citizenship defines the constitution of the city.

According to Aristotle, the core office or function of a citizen is "deliberating and rendering decisions, whether on all matters or a few."* In a tyranny, the tyrant is the only one who judges. In such cases, the definition of a good man equals that of a good citizen, because the tyrant's citizenship consists of his ruling, and his ruling is good if he is good. Practical wisdom is the virtue we need in him, and it is the same kind of virtue that we need in dominant leaders of other entities, such as choruses and cavalry units. Aristotle seems unsure whether a good tyrant must first learn to be ruled, just as a competent cavalry officer first serves under another officer, or whether one can be born a leader.

In democracies, a large number of people deliberate and judge, but they do so periodically. Because they both rule and obey the rules, they must know how to do both. Rich men can make good citizens, because in regular life (outside of politics) they both rule and obey rules. But rich men do not need to know how to do servile or mechanical labor. They must know how to order other people to do those tasks. Workers who perform manual labor do not learn to rule, they do not have opportunities to develop practical wisdom, but they instead become servile as a result of their work. Thus, says Aristotle, the best form of city does not allow its mechanics to be citizens.

Note the philosopher's strongly cognitive or cerebral definition: citizenship is about deliberating and judging. Citizenship is not about implementing or doing, although free citizens both deliberate and implement decisions.

But what if we started a different way, and said that "the city" (which is now likely a nation-state) is actually composed of its people as workers? It is what they do, make, and exchange. In creating and exchanging things, they make myriad decisions, both individually and collectively. Some have more scope for choice than others, but average workers make consequential decisions frequently.

If the city is a composite of people as workers, then everyone is a citizen, except perhaps those who are idle. It does not follow logically that all citizens must be able to deliberate and vote on governmental policies. Aristotle had defined citizens as legal decision-makers (jurors and legislators); I am resisting that assumption. Nevertheless, being a worker now seems to be an asset for citizens, not a liability. Only the idle do not learn both to rule and to be ruled.