« March 2009 | Main | May 2009 »

April 30, 2009

community mapping with Facebook

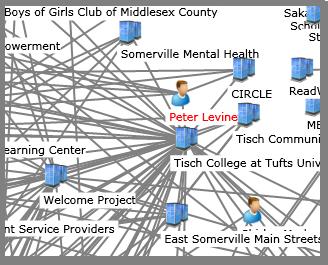

As described in this slide show, we have been working with college students at Tufts and UMass Boston to build one elaborate "network map" of civil society in the Boston area. The map already has many hundreds of nodes and links; we need to improve the visualization tools so that users can make more sense of the data.

Meanwhile, it has always been our goal to make the map accessible by means of simple applications for Facebook and MySpace. I now feel a little clearer about what those apps. should look like.

On my own Facebook page, I would see a little segment of the Boston-area map with myself at the center and my civic connections around me:

Each of those nodes would be clickable so that anyone on my Facebook page could open them up and see the contact information, mission statements, etc. Moreover, when one clicked on any node, the map would reconfigure to put it in the center, with all its links around it. Thus one could "browse" through Boston's civil society. One could also search the whole map and put the main search result right in the middle. And one could use the tool to find the shortest path between any two nodes. For instance, if I ever need to talk to the Somerville Mayor's Office, there's a path for me via Tisch College and then Tisch College Community Advisers board. This is therefore a tool for community organizing.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:07 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 29, 2009

greening the city

My hometown of Syracuse, NY was disfigured when interstate highways were blasted right through its heart, between the university and downtown, flattening a neighborhood that had once been home to moderate-income African-Americans. Their strong web of churches, businesses, and other associations reached back to the time of the Underground Railroad, when Syracuse had been an important center of Abolitionism. In place of this old neighborhood, there appeared bleak expanses of tarmac and a modernist museum by I.M. Pei that showed no regard for its context. The city's population has since fallen--more because of de-industrialization than urban "planning"--and now many of its fine old Victorian homes are abandoned and boarded up. There's even a program under which the municipal government removes condemned houses and gives the property to the neighbors so that they can have suburban-sized yards.

Above is a major Syracuse cross-street, with Interstate 81 right through it. I know this is fanciful, but what if we put glass walls on either side of the space under the highways and filled it with plants? Syracuse is a very cold place--often the snowiest city in the whole country. Imagine warm, green, spaces for recreation under those highways. If the area became attractive, the neighborhoods on either side might fill again, taking advantage of scattered Victorian relics.

(With apologies for my poor perspective and draftsmanship.)

Posted by peterlevine at 9:41 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 28, 2009

youth turnout topped 50% in 2008

The Census has released its 2008 voting data, which is the basis of a fairly detailed new fact sheet by CIRCLE. We find that the turnout of under-30s rose to 51.1 percent. For under-25s, the turnout was 48.5 percent. These rates are considerably above the levels we saw around 1996-2000.

I'm an optimist, so I'll say that the glass is half full. (In fact, we beat the half-full mark by 1.1 percentage points.) We no longer see a steady decline since the 1970s: now the graph seems to suggest that roughly 50% turnout is the norm for American youth, and the late 90's were an exception on the low side.

But the gaps in turnout were large in 2008. About 36 percent of young people with no college experience voted, compared to a 62 percent rate for young people who have attended college. Only about half of young adults go to college.

There was also a partisan gap, although that cannot be directly measured using Census data. Since 66 percent of young voters chose Obama/Biden, it's likely that conservative youth tended to stay home. That would account for why turnout didn't rise more in '08.

There's much more in the fact sheet.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:53 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 27, 2009

AmeriCorps and politics

If you Google terms like "Obama" and "community service," you will find a very large number of conservative blogs and opinion pieces claiming that this is Obama's "brown shirt" corps. They fear that young people will be indoctrinated by "ACORN types" to spread socialism (even though I thought the original Nazi brown shirts beat up socialists). They also assert that Obama is taking a step toward mandatory service. Right now, if you Google "brown shirts" to find out about that Nazi organization, one of the top results is an attack on Americorps.

In reality, AmeriCorps is not a youth organization at all. It provides grants to a very wide range of nonprofits. Such a decentralized approach would be a poor strategy for building an authoritarian political movement, if anyone wanted to do that. There are also very strict restrictions on political activity by AmeriCorps volunteers. They cannot, for example, do nonpartisan voter registration or lobbying. And Obama's nominee to head the agency that overseas AmeriCorps, Maria Eitel, worked for George H.W. Bush before she entered the corporate world as a Nike executive. Hardly a socialist.

So basically the right-wing fear of AmeriCorps is paranoia. A more troubling critique, in my view, comes from the left. Some left-liberals argue that by recruiting hundreds of thousands of young idealists to do community service that is formally insulated from politics, we will frustrate progressive politics for a generation.

I hear that argument, yet I think we need to be careful when we use federal funds for programs that influence young people's thinking about social issues. That's an appropriate goal if it's about authentic learning and deliberation, but it could be distorted by political agendas. AmeriCorps will never become a brown shirt organization, but it could provide patronage or teach members to think narrowly about issues. Out of an abundance of caution, I would favor the existing limits on political action by AmeriCorps volunteers, I would bend over backward to make grants to religious and conservative groups, and I would constantly emphasize that this is not the first step toward mandatory civilian service. (There are philosophical arguments in favor of universal service. The crucial argument against it, in my view, is that it would be extremely costly and difficult to provide millions of high-quality service opportunities; and we could spend those billions better for other purposes.)

Posted by peterlevine at 12:27 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 24, 2009

the civic opportunity gap

Our main message at CIRCLE is that young people benefit from opportunities to do civic work, but those opportunities (such as discussions of controversial issues, service-learning projects, student governments, youth organizing, youth media, community-based research) are very poorly distributed, so that those youth who need them least--our successful students--are most likely to get them, whereas those who struggle in school (or who attend struggling schools) are very unlikely to receive them.

I've got a piece entitled "The Civic Opportunity Gap" in the current issue of Educational Leadership, a magazine aimed mainly at administrators in k-12 schools. Northwest Education published an interview with me under the heading, "Civic Engagement for All." Finally, several of my closest collaborators and I addressed civic equity in a panel at the American Education Research Association conference last week, and Education Week (the main trade journal) chose to cover our discussion. The Ed Week article begins, "The good news, according to researchers presenting findings here last week, is that after waning for years, civic participation among young people appears to be on the rise. The bad news is that students who are members of racial or ethnic minorities, who live in poor neighborhoods, or who are tracked into low-achieving classes get fewer opportunities to exercise their civic muscles than their better-off peers."

Posted by peterlevine at 9:07 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 23, 2009

youth volunteering down, but Kennedy Serve America bill may help

Our new study of youth volunteering rates is getting a lot of coverage. Martha Irvine's Associated Press story has apparently been picked up by 1,300 outlets, and I did a national CBS radio news interview early this morning. Irvine puts the story well:

Volunteering has helped define a generation of young Americans who are known for their do-gooder ways. Many high schools require community service before graduation. And these days, donating time to a charitable organization is all but expected on a young person's college or job application.

Even so, an analysis of federal data has found that the percentage of teens who volunteer dipped in recent years, ending an upward trend that began after the terror attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

"They're still volunteering at higher rates than their parents did," says Peter Levine, director of Tufts University's Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning & Engagement, also known as CIRCLE.

But, he adds, there's been "a loss of momentum," which he hopes recent passage of the federal Serve America Act will help address.

Posted by peterlevine at 4:32 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 22, 2009

AmeriCorps triples

Yesterday, the President signed the Edward M. Kennedy Serve America Act at a ceremony in a Washington, DC charter school that has reclaimed a violence-ridden block. The Act will triple the size of AmeriCorps (if Congress appropriates adequate funds) and will direct the corps members to work on major national challenges: the high school dropout rate, energy conservation, and health disparities. Today's coverage of the bill and the signing ceremony--predictably--concentrates on the personal interactions among Obama, the eponymous Senator Kennedy, and President Clinton, who planted a tree as part of the day's events. There's also some coverage of Michelle Obama's background as an AmeriCorps grantee, which is appropriate. I would have liked (but didn't expect) a little more discussion of what "service" is, how it is changing, and what it can accomplish or not accomplish.

Note that the president naturally shifts from talking about direct service to themes of justice, organizing, and social change. In the campaign, he used the phrase "service and active citizenship"; and yesterday he said:

When I moved to Chicago more than two decades ago to become a community organizer, I wasn’t sure what was waiting for me there, but I had always been inspired by the stories of the civil rights movement, and President Kennedy’s call to service, and I knew I wanted to do my part to advance the cause of justice and equality.

And it wasn’t easy, but eventually, over time, working with leaders from all across these communities, we began to make a difference -- in neighborhoods that had been devastated by steel plants that had closed down and jobs that had dried up. We began to see a real impact in people’s lives. And I came to realize I wasn’t just helping people, I was receiving something in return, because through service I found a community that embraced me, citizenship that was meaningful, the direction that I had been seeking. I discovered how my own improbable story fit into the larger story of America.

It’s the same spirit of service I’ve seen across this country. I’ve met countless people of all ages and walks of life who want nothing more than to do their part. I’ve seen a rising generation of young people work and volunteer and turn out in record numbers. They’re a generation that came of age amidst the horrors of 9/11 and Katrina, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, an economic crisis without precedent. And yet, despite all this -- or more likely because of it -- they’ve become a generation of activists possessed with that most American of ideas, that people who love their country can change it.

"Service" sometimes means serving soup to homeless people or cleaning up a stream--valuable but limited activities. The president talks instead about working with diverse people to address really serious, core problems, such as urban poverty--and to build institutions, such as the SEED charter school. The Act favors such activities, but the AmeriCorps programs will have to change to encourage real public work, planning, learning, and deliberation. The default will be lots of new miscellaneous and temporary positions that provide direct human services. I don't think anyone inside the modern "service" movement would be satisfied with the default, but we will have to work to avoid it.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:30 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 21, 2009

Juan Sanchez Cotán

This is a remarkable painting that I saw in the San Diego Museum of Art last week. I like it for two reasons that often seem to apply to great works.

First, it's good in itself. If you had no idea where it came from, you might guess that it's a nineteenth-century American work, or possibly even a contemporary painting based on a photograph. Regardless, you might appreciate the striking composition, with a few large items displayed in an asymmetrical curve before a black background--the melon slice and cucumber extending into our space. You might also admire the realism of the fruit contrasted with the almost abstract frame.

But then you find out that it was painted in 1602 by a rather mysterious figure named Juan Sanchez Cotán. Before Cotán, no one had painted fruit or other inanimate objects by themselves--only as details in larger works. Cotán painted several "still life" paintings of fruit around 1600, and then entered a Carthusian monastery where he painted only religious works until his early death. With his fruits and vegetables, Cotán launched a genre that remained very important for Dutch genre painters in the 17th century, for impressionists and post-impressionists, and then for Cubists and other high modernists. Representing vegetables on a table became a means of exploring space and light, of commenting on art, and of making subtle points about affluence and decay.

Thus Quince, Cabbage, Melon and Cucumber has qualities that you cannot infer from the image alone. For instance, we can call it "original" and "influential" because we know what comes before and after in the history of art.

Implication: If someone painted exactly the same picture today (whether or not he copied the original), it would be a different work of art with an entirely different significance from Cotán's painting. Borges explored the same idea in "Pierre Renard, Author of the Quixote." The fictional Renard writes passages of Don Quixote verbatim without consulting the original book, thereby creating a work that is identical to Cervantes' masterpiece in terms of the letters on the page, but entirely different in value and purpose.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:28 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 20, 2009

a theory of free speech on campus

Last Thursday, students at my university (Tufts) assembled to protest an incident described as follows in the Boston Globe:

- The freshman, who is white, approached five men from the group who were practicing a dance for an upcoming cultural show and insisted the dancers teach him their moves, according to the school newspaper and a news release from the Korean Students Association. When the dancers refused and asked him to leave, the freshman responded with expletives, called them "gay," spat on them, and threatened to kill them, according to one written account. A fight ensued and the dancers pinned the freshman to the floor, put him in a headlock, and let him go only when he said he could not breathe, said a written account of the incident from the Korean Students Association. The freshman then allegedly spewed a string of racial epithets, yelling at the Korean students to "Go back to China."

The incident (as described by several witnesses, but not yet independently adjudicated) is extremely ugly. It has no place on a campus and requires a response that goes beyond the case itself. But the protest--to judge by comments in the Tufts Daily--was itself controversial, provoking complaints of "political correctness." At the risk of responding rather abstractly and cerebrally to a raw case, I'd like to say something about speech in academia.

The central value, in my opinion, is not freedom but quality. A university is not like the state, which has to be extremely careful about using its dreadful powers to assess or influence expression. A university is all about influencing expression. Every grade on an essay, every tenure decision, every invitation to a visiting speaker, and every revision of an administrator's memo is a judgment of quality, with consequences. A university is a voluntary community dedicated to improving discourse. Members are entitled to leave, and the university is entitled to discipline or even expel them for what they say.

We are the heirs of the Free Speech Movement, which dramatically improved colleges by ending bans on political expression and loyalty oaths. We should be grateful to that movement--but understand it correctly. The old rules against political expression had reduced the quality of discourse on campuses by bracketing a whole set of essential questions. Such bans were invidious. But the alternative was not freedom per se; it was a new environment in which discussion of politics was allowed--and even favored.

One famous free speech case, Keyshian v Board of Regents, struck down loyalty oaths in New York State schools on the theory that:

- Our Nation is deeply committed to safeguarding academic freedom, which is of transcendent value to all of us and not merely to the teachers concerned. That freedom is therefore a special concern of the First Amendment, which does not tolerate laws that cast a pall of orthodoxy over the classroom. "The vigilant protection of constitutional freedoms is nowhere more vital than in the community of American schools." ... The classroom is peculiarly the "marketplace of ideas." The Nation's future depends upon leaders trained through wide exposure to that robust exchange of ideas which discovers truth "out of a multitude of tongues, [rather] than through any kind of authoritative selection."

I'm 100% against loyalty oaths, but I don't think the "marketplace of ideas" metaphor can really justify freedom in classrooms. First, a marketplace requires incentives. A marketplace of ideas only works if you obtain rewards for being correct. In the classroom--and more broadly, in academic institutions--the main incentives are grades, degrees, speaking invitations, and jobs. These are not handed out neutrally; they are given in recognition of quality. The system that awards these incentives is rather hierarchical and centralized. So there is no market within a university, although universities compete with each other in a market for students. They promise--not freedom--but the ability to assess and reward excellence.

Second, "truth" is not the only mark of quality--contrary to the passage from Keyshian quoted above. Elegance, relevance, originality, respect for others, and social value also count. Universities are in the education business. Their students, and others whom they influence, are supposed to learn to think and speak well. Telling Korean-American students to "go back to China" is thus a failure of higher education. The precise remedy is a matter of judgment, but it certainly cannot be tolerated on grounds of "free speech."

(See also Justice O'Connor's theory of academic freedom.)

Posted by peterlevine at 7:49 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 17, 2009

counter-cultural politics

I ended my AERA presentation last week by saying that the best thing about good youth civic programs is not their impact on the kids whom they engage, nor the chance that they may increase political equality. The best thing about them is that they embody an alternative kind of politics. Excellent classroom discussions of controversial issues, service-learning projects, and youth media-production or youth-led research create examples that help to move the whole society ...

- From the prevailing "deficit model," in which students (and adult populations, too) are treated as problems or victims, toward a model of people as contributors.

- From a specialist understanding of education (in which professional teachers educate and kids are measured on tests) to an understanding of education as a community's task (in which schools play one important role).

- From a sense that all investments are mobile and contingent to an attitude of commitment.

- From a government-centered view of politics--in which the main controversy is what the government should and shouldn't do--to a citizen-centered view, in which the question is how we define and address our problems.

- From an understanding of politics as zero-sum distribution to an understanding of politics as creativity and the making of meaning.

- From manipulative or strategic politics to politics as open-ended deliberation about what ought to be done.

My colleagues and I have made these points before, but I was expressly asked to list them on my blog--and here they are.

Posted by peterlevine at 4:31 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 16, 2009

Kipling: understanding and control

I just finished Kim, which was my favorite novel when I was 12 years old. I wanted then to be Kim, a boy spy in the Orient. Later, I would have avoided the book as imperialistic and juvenile. But a favorable word by Pankaj Mishra sent me back to it. It is a bit of a "Boy's Own" adventure, and it is certainly imperialistic--in an interesting way. It is also finely constructed, challenging, and beautiful to read.

I was attentive to the different ways that Kipling's characters understand or fail to understand cultures other than their own. Almost the full possible spectrum of such understanding is represented. Right at the beginning, we meet the English curator of the museum in Lahore, a man learned in the languages and religions of South Asia. He derives some of his knowledge from "books French and German, with photographs and reproductions," drawing on the "labours of European scholars" accumulated over at least a century. (That body of work is a remarkable achievement.) But the curator also recognizes an old beggar as "no mere bead-telling mendicant, but a scholar of parts," and engages the Lama in a respectful conversation, from which he continues to learn.

In Chapter 4, a "dark, sallowish District Superintendant of Police" speaks fluent Hindi or Urdu and wittily urges a woman to veil herself--enforcing not a British law but a local custom. She observes, "These be the sort to oversee justice. They know the land and the customs of the land. The others, all new from Europe, suckled by white woman and learning our tongues from books, are worse than pestilence." In Chapter 11, we learn that the same policeman is actually a Government spy, "not less than the greatest" agent in the Secret Service. What makes him effective is his deep affinity for his Hindu subjects.

To control requires understanding and respect. It changes the ones who rule as well as those whom they govern. The two cultures grow more alike, either enriching or adulterating themselves (depending on your perspective and the way the merger turns out). Some Europeans in Kim do not understand this dynamic. For instance, the Rev. Bennett says, "My experience is that one can never fathom the Oriental mind." He can't even understand when Kim, in Urdu, calls him "the thin fool who looks like a camel." To misunderstand is to lack control, as the Russian and French spies find to their humiliation near the end. They believe they can "deal with Orientals," but they utterly misread the people around them.

And then there is the lama, who doesn't wish to understand because he doesn't want to rule. "It was noticeable that the lama never demanded any details of life at St. Xavier's, nor showed the faintest curiosity as to the manners and customs of the Sahibs." As a result, the Europeans affect him not at all. (Even the spectacles that the curator gives him never change the way he sees the world.)

So the imperialism that Kim describes and--presumably--celebrates is a process of careful, respectful interpretation and learning. It's not surprising that the head of the Royal Ethnographic Survey is also the chief spy for Britain, or that an Anglified Bengali should wish to use charms and to describe them in scientific papers for the Royal Society. This "Babu" is, in fact, the perfect example of an imperialistic mix, with his invocations to Herbert Spencer as a prophet of karma, his Latin tags, and his brilliant mimicry of diverse Indians.

Kipling himself spoke Hindi before English, and his father was the curator of the Lahore Museum. So Kipling was the kind of imperialist he celebrated. What he overlooked was the economic exploitation essential to the British Raj. The British didn't just "oversee justice"; they also made the rules to maximize their profit. The only hint of that fact in the novel is a complaint that the Babu makes when he pretends to be drunk in order to manipulate enemy spies. He is actually a British spy, despised in all his disguises. Yet perhaps Kipling faintly understands that the Babu's complaint is just.

For better and for worse, the United States has never produced many people who yearn to understand, love, and control foreign countries. We intervene often enough, but we tend to beat a quick retreat when we find distant lands impossible to understand or to master. There have been fine American scholars of distant cultures; but they are rarely the same Americans who have invaded and governed such places. Today, after the new Counterinsurgency Manual and the shift in US tactics, American soldiers are busy learning Arabic and Pashto. I am not sure that their knowledge will last or accumulate, nor that it is motivated by the kind of love, affinity, and urge to possess that was so common among Anglo-Indians. I suppose the strongest example of real American "imperialism" is domestic; white Americans have periodically immersed themselves in minority cultures and have thereby helped to change and control them.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:25 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

April 15, 2009

San Diego

I'm in this city, which is diagonally across the USA from my home, for a total of 23 hours--from landing to takeoff. I'm here to join a presidential session at the American Education Research Association's convention; my topic is what we can learn from the 2008 election. In August, I'll fly to California for another presidential panel on basically the same topic, but that one will be at the American Sociological Association's annual meeting.

Meanwhile, I've had a brief chance to experience America's 17th largest metro area by walking from the Gaslight District to Balboa Park, seeing some fine European paintings, and then taking a bus back to my hotel. I'm used to this kind of brief visit; I've also recently walked through Austin, Seattle, and Albuquerque. I tend to use analogies when I try to take in new cities. That's no doubt misleading, but it gets you started. San Diego, to this very superficial visitor, is reminiscent of Miami (Spanish revival buildings, palm trees, strips of ocean water), Denver (long avenues lined with foursquare modern buildings and hints of mountains), and LA (freeways, canyons, and a similar ethnic mix). It's a pretty far cry from Boston.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:25 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 14, 2009

youth voices and gentrification

(In San Diego for the American Education Research Association) In 2005, CIRCLE was funded by the Cricket Island Foundation to make grants to youth-led teams of community researchers. We argued that research was a powerful form of civic and political action, especially when youth gave the results away to their communities. Doing research was not only good for kids; they could also produce excellent results if they used qualitative methods and local knowledge.

Applicants came from all over the country. One successful group was Cabrini Connections, a grassroots organization in Chicago's most famous public housing project. As the youth show in this video--an outgrowth of our grant--Carbrini is famous for violence but is also a three-dimensional community and a lifelong home. It is now threatened by gentrification.

For several years, I also helped to select applicants for micro-level "citizen journalism" grants through the New Voices project. Applicants proposed to build websites or create broadcast shows about local issues. And I helped to judge the Case Foundation's Make it Your Own Awards, which supported citizen-centered local work. In all these competitions--for grassroots or youth-led research, deliberation, or media production--a frequent theme was gentrification, and a rich source of strong applicants was Chicago.

I suppose the gentry will retreat again, now that housing prices are falling. But when the story is told of urban America from 1995-2005, an important theme will be the ways that shrinking poor neighborhoods organized to express their views, preserve their memories, and study their issues. Chicago will loom especially large in that history.

Posted by peterlevine at 4:53 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 13, 2009

universities as economic anchors

Gar Alperovitz, Ted Howard, and their colleagues at Community-Wealth.org have argued for some time that we need economic institutions that are anchored in communities. It doesn't matter so much whether they are public or private, non-profit or for-profit. What matters is that they cannot move, so that they have to invest in their communities (or at least minimize their damage).

From that perspective, one of the most significant facts about colleges and universities is that they are economic enterprises that cannot move. They collectively do tens of billions of dollars of business. Their impact can either be helpful or harmful, and their students and faculty have some influence on how they behave. Thus the discussion of universities and democracy must broaden beyond education and research to include economic issues. A great guide is Gar Alperovitz, Steve Dubb, and Ted Howard, "The Next Wave: Building University Engagement for the 21st Century," The Good Society, vol. 17, no. 2 (2008), pp. 69-75, available in PDF. They end with some interesting policy recommendations, including an urban extension service and a new federal initiative in ten pilot cities.

Posted by peterlevine at 3:38 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 10, 2009

why states need new and different policies for democratic education

States have various policies in place that we might hope would encourage civic learning and engagement. Examples are curricular requirements (for social studies and/or civics classes), mandatory tests, and even the statewide service mandate in Maryland. We don't know much about how policies affect experiences at the classroom level, although we do know that certain experiences are valuable--notably, moderated discussions of controversial issues, well-conceived service projects, and challenging simulations of political or legal institutions.

My colleagues and I were able to combine information about all the extant state policies with evidence from the Knight Foundation's survey of 100,000 high school students. This survey gave us information about the kids' backgrounds, their experiences in classrooms and schools, and certain civic outcomes related to the First Amendment, such as valuing freedom of speech and using the news media. As expected, we found positive associations between classroom-level experiences and the outcomes we value. For instance, discussing controversial issues once again emerged as a beneficial opportunity. But we found no statistical links between state policies and classroom activities or students' outcomes.

I conclude that the states are basically barking up the wrong trees. We need new types of policies that would actually encourage the activities we want to see in classrooms. Mandating courses and testing students' academic knowledge of politics are worthy policies, but they don't get us the values and habits we want to see.

(See Mark Hugo Lopez, Peter Levine, Kenneth Dautrich, and David Yalof, "Schools, Education Policy and the Future of the First Amendment, Political Communication, vol. 26, no. 1, January-March 2009.)

Posted by peterlevine at 1:59 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 9, 2009

core principles of public engagement

Complementary to the "Champions of Participation" report that I mentioned yesterday is a project to identify the principles of public engagement. The authors are leaders in the "dialogue and deliberation community," organized by the NCDD. Their main audience is the Obama Administration and others who want to help implement the president's requirements for "transparency, participation, and collaboration." They begin: "We believe that public engagement involves convening diverse yet representative groups of people to wrestle with information from a variety of viewpoints, in conversations that are well-facilitated, providing direction for their own community activities or public judgments that will be seriously considered by policy-makers and/or their fellow citizens."

NCDD is open to comments on the draft, but I'm happy to endorse this as is.

Posted by peterlevine at 3:29 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 8, 2009

the Champions of Participation speak

This is a meeting of senior federal managers who have been identified as "Champions of Participation." They were convened by AmericaSpeaks, Demos, Everyday Democracy, and Harvard University’s Ash Institute for Democratic Governance and Innovation at the John F. Kennedy School of Government. They met to discuss the president's executive order requiring "transparency, participation, and collaboration," which he signed on his first day in office. (For disclosure, I am on the boards of both AmericaSpeaks and Everyday Democracy.)

So far, the administration has focused on transparency and the use of technology to share information with citizens and collect their opinions. This group broadened the topic to include face-to-face participation and collaboration by federal agencies. The full report contains very concrete and challenging recommendations. But I was especially interested in some of the philosophical positions these managers took. According to my transcriptions from the video, they said:

- Leaders engaging in public participation initiatives [should] value not knowing the solution before they begin and be willing to engage in collaborative learning and collaborative problem-solving to create the solution. And we believe that this approach, or this value, would represent a humility that is not often seen when government leaders engage the public.

Public citizen stewardship and local knowledge. ... We thought it was important to make civic engagement part of every agency's mission and citizen-centered delivery of the mission part of that.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:30 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 7, 2009

the Blue Mosque

Visiting the Sultan Ahmed Mosque in Istanbul--popularly known as the Blue Mosque--Barack Obama reportedly said, "I am very impressed spiritually. This is one of the most important instances in my life." He probably didn't have much time there, but I know the feeling. I've visited several times, during two three-week family visits to Turkey. On both visits, we stayed within blocks of the Blue Mosque, which is one of the masterpieces of Ottoman Architecture. It stands opposite the great Byzantine Basilica, Hagia Sofia, which was the largest and most influential Christian church in the world for a millenium. With its vast dome, the Blue Mosque competes with Hagia Sofia but also complements it. It is serenely classical: transparent, regular, symmetrical, and calm. It's not by the preeminent genius of Ottoman architecture, Mimar Sinan, but by a somewhat later architect named Sedefkar Mehmet Aga. I suppose it is less original and bold than a Sinan mosque, but it represents a confident stage in the development of this serene style, which combines Roman engineering, Byzantine design (massive domes over square interiors), and Islamic abstraction and decoration.

I might actually choose the Blue Mosque as my single favorite building. My experiences there were probably more aesthetic than spiritual, but the distinction is elusive. (When my little kid was 7, she and I built a little version of an Ottoman mosque in cardboard.)

Posted by peterlevine at 10:17 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 6, 2009

experimenting in social policy

Often, people who say that they have experienced specific services or opportunities also report better outcomes--such as educational success, employment, or health--compared to similarly situated people who never received those opportunities. For example, according to a paper published by CIRCLE, young adults who were required to perform community service as part of their middle school coursework are 14 percent more likely to graduate on time from college, even when one compares them to people who are similar in respect to all the other factors measured in the survey, such as test scores, parental education, race, and gender. One could conclude that community service has a 14-point positive impact on college graduation.

Indeed, that effect is possible. But service-learning has not yet been tested with a more rigorous method of evaluation. The "gold standard" is a randomized experiment, in which some people are randomly assigned to receive an experience that others (the "treatment group") don't get. If assignment is random, then the difference in outcomes is a measure of the impact of the experience.

Experiences that appear highly beneficial in studies of whole populations often show modest or no results in experimental tests. This is such a common pattern that it requires some general reactions.

why experiments rarely show impact

Survey-based studies and experiments may produce divergent results because the people who receive opportunities have advantages that account for their later successes and that are not measured in surveys--such as motivation or perseverance, helpful networks, enrollment at subtly better schools, or ties to motivated teachers and other helpful individuals. These advantages explain their good outcomes and account for what we originally hoped were benefits of specific programs.

(Another possible reason for the failure of programs to "work" when tested in randomized experiments is that the control groups actually find alternative programs. If that happens, an experiment will miss real benefits. But it's my general sense that this is a relatively rare explanation.)

the injustice of testing only some programs

We treat programs and institutions with profound inconsistency. Government-funded programs for poor people are expected to show long-term impact in "gold standard" experiments, but no one ever asks whether services provided to high-income people work--even when such services are publicly subsidized. For instance, my university provides four years of elaborate educational, social, recreational, health, and housing services for its undergraduates. No one imagines that the impact of that package of services would ever be tested in a randomized experiment. Universities like mine obviously confer advantages on the individuals who graduate; our graduates are preferred in the job market. Since they benefit (relative to others), they want the opportunity to attend. And since they have political and economic clout, they get the opportunities they want. But a randomized experiment might find that the social benefit of a Tufts education is small, especially if the control group got a BA at half the cost.

what we should do

Notwithstanding this serious unfairness, I believe we should expect programs aimed at poor people to "work" under rigorous tests. Political power in unequally distributed. Those without power never get much public assistance. Given limited funds, we need to spend every dollar well. To test programs experimentally is not punitive; it's a matter of making sure that we really do good.

In fact, I'm in favor of widespread field experimentation, with the following caveats:

1. There is an appropriate life-cycle for programs. They shouldn't be expected to "work" in randomized studies from Day One. There should first be a fairly long process of informal experimentation and adjustment. Such experimentation should be supported.

2. When many programs fail to show impact, we shouldn't become generally pessimistic about social interventions. We are holding them to standards that we never use in the private sector or when assessing other types of government programs (such as weapons purchases, agricultural subsidies, or macroeconomic policies).

3. Benefits need not always be long-term. Many beneficial interventions wear off, and that is an argument for follow-up, not for canceling the programs. Besides, if a program actually makes life better for 13-year-olds, that seems like an important advantage even if they are not still better off when they are 20.

4. Experiments should be used to improve programs. That is much more promising than lurching from one untested strategy to another every time results are disappointing.

5. Randomized experimentation is a rather detached, arm's length method. But it is also an easy method to explain. Participants should influence important aspects of the research, such as decisions about what to measure and interpretations of the results.

Posted by peterlevine at 2:31 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 3, 2009

conservatism in the Nation of Shopkeepers

The British Conservative Party wants to make the preservation of small, locally-owned business a major objective. Their Leader, David Cameron, says, "Small shops are the lifeblood of local economies and provide a lifeline to local residents - and their survival is vital. ... If we care about our communities, and the local, independent retailers that give them their character, then it's our responsibility to support them." A Conservative Party report has argued that small shops "reflect something of what is best about modern Britain itself. They are independent and entrepreneurial, they display a rich cultural and ethnic diversity, and their eclectic differences add real character to our towns, cities, and villages." But these small businesses are closing fast, in part because of big chains.

The Tories are conjuring up images that I recognize with some nostalgia, having grown up substantially in Britain. "High Street" businesses over there include ancient pubs, independent butchers with sawdust on the floor, kabob stands, hobby stores selling stamps and model airplanes, corner groceries owned by South Asians, cafes with bottles of "brown sauce" on the formica tables, dusty antiquarian book shops, and newsstands lined with specialist magazines. As the Conservatives say, these business support an everyday culture that has British roots but that is deeply diverse today, both ethnically and regionally. It wouldn't be British if there weren't Asian, West Indian, and Irish owners and workers among the white, Anglo-Saxon ones.

I think the Tories' new emphasis is a politically smart move, because there is much affection for local businesses and the local cultures they support, and this affection crosses national and party lines. (Crunchy liberals are also enthusiastic about small, locally-owned businesses.) I guess you could criticize the Tories' position on at least two grounds: 1) They won't actually be able to save small businesses, so it's just rhetoric, and 2) they are promoting a kind of communitarianism that is nostalgic and soft and not sufficiently concerned with power. Then again, maybe they will figure out policies to revive and preserve local business, and maybe local business are a real source of power, a counterweight to transnational markets. In any case, this move seems like a genuine form of conservatism, much more authentic than the weird mixtures of libertarianism and authoritarianism that are common on the American right today.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:01 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 2, 2009

beyond the vote: 2009

(From Princeton, NJ) The Dallas Morning News' Laura Isensee talked to me and several experts on civic engagement about whether all those young people who voted at high rates in 2008 will remain involved between elections. One of the best things about her article is her recognition that it's not all about what young people feel or think; it also matters whether the political system is structured to permit their participation. The story was picked up by the AP and ran in quite a few other papers.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:35 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 1, 2009

controversy in the classroom

According to my blurb on the back cover:

- Controversy in the Classroom is a model of scholarship. Diana Hess combines her personal experience as a teacher with rigorous qualitative and quantitative data and philosophical argumentation to conclude that students must learn to be citizens by discussing controversial issues. This is an important and neglected finding that should influence parents, teachers, and policymakers.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:25 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack