« April 2008 | Main | June 2008 »

May 30, 2008

evaluating community projects

(At Fordham in New York City for the day) Here is a further reflection on the "Tenure Report" from Imagining America, which I summarized on Wednesday. I think if I were involved in campus politics or administration, I might advocate one strategic reform to promote "engagement." I would argue that projects undertaken in communities ought to be assessed on a par with peer-reviewed publications for the purposes of hiring, tenure, and promotion. Standards for evaluating such projects should be rigorous and stringent, so that most would not be deemed fully successful. Launching a community project is no more commendable than opening Microsoft Word and starting to type; in either case, one is accountable for the quality and impact of what one achieves. An impressive community project should be:

Generative: producing a substantial array of performances, events, programs, exhibitions, curricula, experiments, organizations, institutions, policies, maps, research instruments, data, peer-reviewed publications, college courses, and/or graduate student work. Intellectually ambitious: driven by challenging and innovative hypotheses, narratives, or methodologies and designed to test the organizers' own presumptions and biases. Coherent: capable of being summarized in one story about its purposes, activities, and results. (Although a project should be flexible over time and should include diverse people and agendas, the whole should be worth more than the sum of its parts). Ethically responsible: sustained (no "drive-by scholarship"), accountable to relevant people inside and outside the academy, transparent, including real dialog with all the participants. Effective: demonstrating real outcomes appropriate to its own objectives at a reasonable cost in terms of money, time, and political capital.

Methods of assessing the quality of projects will vary, but one should at least consider using portfolios and peer reviews by independent, reliable community members.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:31 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 29, 2008

"the buzzy philosophy element"

I'm spending occasional moments cleaning out my office after 15 years. It's an excavation into the forgotten past. For example, I had no recollection of this letter from a British editor. The subject is Something to Hide, my novel that was later published by St. Martin's in the US:

This started off quite well--or intriguingly at least--with the themes of philosophy and conspiracy nicely built, the characters of Zach and Kate making slow but steady progress and the plot structure being established. Somewhere, though, Levine fucked up and from halfway through this winds down into a rather dull trudge through overly familiar political-thriller scenes, tedious shoot-outs and not nearly enough about the historical conspiracy so nicely hinted at in the early stages. It ends up as dull and routine which was a shame after the promising start.I can imagine that this might do something in the US all the same--it has certain parochial characteristics which would normally prevent it being done in the UK but which America seems to like. The buzzy philosophy element would certainly provide an angle in marketing terms and even though it's dull, the book has a certain charm. I don't really fancy this for Arrow at all, but I wouldn't be very surprised if it sold for a quite a lot in the US.

For the record: there are no shoot-outs, it sold for very little in the US, and I'll take "dull" but with "a certain charm" as a compliment. It's better than "dull and charmless."

Posted by peterlevine at 8:41 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 28, 2008

tenure, promotion, and civic engagement

"Scholarship in Public" (pdf) is a very important new paper published by Imagining America on behalf of a strong group called the Tenure Team that includes the historian Thomas Bender, Dean Nicholas Lemann of the Columbia Journalism School, several college presidents, and many of the smartest people who think about public engagement.

"Publicly engaged academic work" means various kinds of collaborations between university-based scholars or artists and laypeople in their communities. It generates public products, such as museum exhibitions, radio programs, k-12 curricula (and sometimes even whole schools), databases, maps, and websites--as well as peer-reviewed journal articles and books. It often involves comprehensive projects that generate numerous artifacts for different audiences--in contrast to standard academic work, which tends to produce one publication at a time. These projects create knowledge and understanding that we cannot obtain anywhere else, while strengthening culture, community, and democracy.

Public engagement also serves some professors' valid and worthy personal objectives. Craig Calhoun, a Tenure Team member and one of the most insightful people in the business, notes an enthusiasm in our culture today for "making things, .... making and building institutions, rather than only commenting on the institutions." He says, "You have a lot of the smartest young people trying to build something, and I think that carries over to academia, where people are saying, 'I want to do that. I want to create.'"

But public engagement must be done well. Even ambitious, well-intentioned, and labor-intensive projects can fail, just as books and lab experiments can fail. Public engagement can also be superficial or trivial. I know departments in which some scholars labor hard in the library or lab in the hopes of being able to make presentations at international scholarly conferences. Others give occasional lectures--which they might also present to their own undergraduates--at local churches or civic groups. These local lectures or performances may be covered in the local press, but they are not scholarship. Rewarding such superficial projects with promotion, tenure, and other awards is unfair. Worse, it submerges the much more difficult and ambitious work that deserves the name of "public scholarship" or "public art."

As Calhoun says, "This is about making scholarship better, making knowledge better. It is not about concessions in the quality of scholarship and knowledge." That means that public scholarship must be critically assessed, not given a pass because it is well-intentioned. Critical assessment will require new techniques, and the report suggests several: use community partners as peer-reviewers; evaluate projects rather than individual publications; allow professors to assemble portfolios; develop plans for projects and evaluation when new professors are hired.

The report also tackles a sensitive and important issue within this field, which is the role of minority professors. Obviously, academics who are African American, Native American, or Latino may want to pursue highly academic and theoretical research. But a disproportionate number of minority scholars are involved in community-engaged work, because they tend to be motivated to change society; they often have roots and networks outside academia; and they may have cultural skills that allow them to "cross over" effectively. If these scholars work in partnerships with laypeople, and such work is not rewarded, their careers suffer. This is also a problem for whites, but scholars of color face an extra layer of obstacles. The negative stereotypes that persist against them in academia often take the form of an assumption that it is just to hire a person of color even if his or her academic work is weaker. That's highly patronizing to the individual scholar. And if a minority professor's work takes the form of community projects, then the stereotype about minorities reinforces the stereotype about civic engagement, and vice-versa, adding up to an almost insurmountable barrier to success.

The solution, again, is to create rigorous, independent, tough measures of quality for civic engagement. Then any professor, including a scholar of color, can choose to try public projects, and the ambitious and successful ones will bring just rewards.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:24 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 27, 2008

my favorite book

I first read Middlemarch when I was 17. It was assigned in the Telluride Association Summer Program at Cornell, and I think I loved it because it was the first time that I had read any book in a seminar, with real college professors and many hours spent on a single text. It was my first experience with close reading and with the application of challenging theory to literature. Gradually, as the years passed, I forgot most of the content of the novel--even the plot. I used to joke that it had retired undefeated as my favorite novel. But then, about a month ago, I opened it casually to remind myself of something near the beginning, and I found myself unable to put it down. I finished the very same copy that I had read almost a quarter century ago.

What is Middlemarch? It is a great feminist text, an indictment of the structure of relations between men and women that is not an indictment of the men as individuals. Patriarchy stunts the lives of male and female characters alike; and women often actively promote it. (Mrs. Garth, for example, is consciously raising her son Ben to be superior to her daughter Letty, and she is able to do that because she has such strong ideas and such control of her household that her husband could not object.) The "imperfect social state" of patriarchy prevents Dorothea from achieving public greatness and reduces her to "liv[ing] faithfully a hidden life."

It is a superbly constructed story. Henry James denied that Middlemarch was "an organized, moulded, balanced composition, gratifying the reader with a sense of design and construction." It was, he wrote, "a treasure-house of details, but ... an indifferent whole." That was nonsense, and I suspect he was jealous. Five or six plots are carried throughout, intertwining and building pressure on the characters until the denouement reveals Dorothea's true heroism. Although the novel is not overburdened with coincidences or artifice, one could spend months finding careful symmetries and parallels. Take, for example, the brief visit of Dorothea to Rosamond's house that opens Book V. This is the first time that two major story lines intersect. The women are foils, different in class, character, and appearance. Their first encounter, in the presence of a man who becomes an object of jealousy, causes all three to see themselves differently, in ways that reverberate until the end. This episode is just one example of how skillfully the whole work is constructed.

It is a grown-up's novel. "Marriage," says the narrator, "has been the bourne of so many narratives." A bourne is a brook, and many romantic stories are streams flowing toward the inevitable wedding, when the ingenues, having overcome obstacles to their love, are united in a timeless happily-ever-after. In Middlemarch, however, two of the three essential weddings come near the beginning, and then the plot really begins. The novel is not cynical about marriage, nor critical of it. But it refuses to dwell only on the moment of falling in love or becoming united. Lives go on, and going on is hard.

It is a novel that is remarkably clear-sighted about economics. "I will learn what everything costs," Dorothea exclaims at a crucial moment. Debts and inheritances figure strongly in the plot. There is an important auction. People confuse "use value" with "exchange value" (what things are really worth versus what they capture in a market). Because of the social structure of a market, it is not easy to be moral. "Spending money so as not to injure one's neighbours" is a challenge.

It is a novel about a large network. I wish I had marked each significant character on a piece of paper and drawn a line between them whenever they had some "connection" (which is an important word in the text). The result would be a complex web with at least 50 nodes and hundreds of connections, which often link the gentry to the riffraff in just a few steps. News and gossip travel with fateful effects along this network. In many cases, the parties who are linked directly do not understand one another. In fact ....

It is a novel about misunderstanding other people; and the misunderstandings arise for a huge variety of moral, psychological, and social reasons. People misread others out of vanity, fear, naivete, and even because of admirable faith. Middlemarch would be one kind of novel if the omniscient narrator patronized these characters for their all-to-human failure to know one another. But the third-person omniscient narrative voice is occasionally broken by a first-person acknowledgment of uncertainty. The narrator will remark that he (or she?) doesn't know what a particular character was thinking. This must be a deliberate reminder that understanding other human beings is never possible.

The narrator also occasionally expresses an explicit judgment or even interrupts the narration irritably. These outbursts are comic surprises because the rest of the narration is so objective. For instance, I love this beginning of chapter XXIX: "One morning, some weeks after her arrival at Lowick, Dorothea--but why always Dorothea? Was her point of view the only possible one with regard to this marriage? I protest against all our interest, all our effort at understanding being given to the young skins that look blooming in spite of trouble; for these too will get faded, and will know the older and more eating griefs which we are helping to neglect."

Perhaps the most prevalent reason for misunderstanding in Middlemarch is egoism, which comes in many forms, some contemptible and some fully excusable. Egoism is relevant to the idea of a network, because any node can be taken as the center and all the other nodes can be seen as arrayed around it in various degrees of separation. There is a famous and very rich passage in Middlemarch about our propensity to see ourselves as the central node:

An eminent philosopher among my friends, who can dignify even your ugly furniture by lifting it into the serene light of science, has shown me this pregnant little fact. Your pier-glass [mirror] or extensive surface of polished steel made to be rubbed by a housemaid, will be minutely and multitudinously scratched in all directions; but place now against it a lighted candle as a centre of illumination, and lo! the scratches will seem to arrange themselves in a fine series of concentric circles round that little sun. It is demonstrable that the scratches are going everywhere impartially and it is only your candle which produces the flattering illusion of a concentric arrangement, its light falling with an exclusive optical selection. These things are a parable. The scratches are events, and the candle is the egoism of any person now absent ...

The narrator supplies a heartbreaking reason that we must place ourselves at the center of the network, act egoistically, and fail to understand one another fully. "If we had a keen vision and feeling of all ordinary human life, it would be like hearing the grass grow and the squirrel's heart beat, and we should die of that roar that lies on the other side of silence. As it is, the quickest of us walk about well wadded with stupidity." Our "stupidity" is essential for our survival; none of us could bear to comprehend the suffering of everyone else.

Finally, Middlemarch is, I suppose, a comedy. It has jokes, a lightness of tone, and a satisfying conclusion that I would not call tragic. Most of the loose ends are tied up. And yet there is a powerful sense of the weight of norms and the inertia of history. We are left with a deep question: whether Dorothea's life has turned out to be a good one.

[Spoiler warning: I can't address this question without giving away the conclusion.]

On one hand, we may think that she has done very well. She exclaims, "What do we live for, if it is not to make life less difficult to each other?" She has made life considerably less difficult for Rosamond, Lydgate, and Ladislaw because of her actions in Part VIII, which are believable and yet extraordinarily generous and courageous. Few indeed would act as well as she does. Her virtue has some reward. She marries a man who truly respects her greatness of soul, and she presumably finds some fulfillment as a wife and mother.

On the other hand, Dorothea is a far greater person than Ladislaw (as he would be the first to agree). Yet it is Ladislaw who wins a seat in Parliament and plays a role in national affairs. "Her finely touched spirit had still its fine issues, though they were not widely visible. Her full nature, like that river of which Cyrus broke the strength, spent itself in channels which had no great name on the earth." Dorothea is forced into the private realm because she is a woman; also, because the public realm is reserved for very few even among men of wealth and privilege. Only a few hundred serve in Parliament, for example--not including Dorothea's own uncle, whose ambitions are frustrated.

This is a great illustration of Hannah Arendt's argument that politics is the realm of character, courage, and real freedom. The private realm, no matter how we try to enhance it by elaborating our ideas of courtship, intimacy, and sentiment, is no place for greatness. If that were also Eliot's view, Middlemarch would be a protest novel, and its target would be a conformist, consumerist culture that suppresses greatness by narrowing the realm of politics. But again, that's only one side of the story, for Dorothea does succeed in her own realm of domestic life and private relationships. "The effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs."

The novel reveals Dorothea's hidden life, but of course it is a fiction. A real life like hers would never come to light. That makes her story a kind of tragedy, but one that we all share unless we have the enormous good fortune to achieve public renown. In other words, I can't really pity Dorothea without also feeling sorry for myself and almost everyone I know.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:09 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 26, 2008

the big story about developing countries' debt

The Washington Post ran a story on Saturday about the declining significance of the International Monetary Fund. The lead was a decision by Ghana to reject loan conditions proposed by the IMF. Ghana could negotiate from strength because it has a growing economy and other options for borrowing. "That decision underscores the changing role of the IMF as developing economies have roared to life in recent years, with the fund increasingly becoming more adviser than lender."

The tone of the article was somewhat critical, focusing on challenges for the IMF as an institution. Indeed, there are plans to cut the Fund's staff by 13 percent to reflect a shrinking portfolio. But of course the story could have been told very positively; the headline could have been, "IMF Succeeds." Someone I know at the Fund told me the following story:

In the 1980s, developing nations were burdened by enormous debts, often run up by dictators. This was a huge problem, morally and practically. Admitting that the loans should never have been made in the first place was too embarrassing for the lending countries. The IMF and World Bank literally didn't have the cash to write off their loans. Forgiving debts can create a moral hazard (encouraging more borrowing). Yet the debt was a plague on the poorest people of the world.

This problem has been very substantially reduced through a combination of debt forgiveness and economic growth. Perhaps the process was far too slow or too costly for the poor countries--I don't know. What is important right now is that we have passed through the debt crisis to a large extent. The following graph, which I generated using the IMF's interactive website, shows foreign debt per GDP for Subsaharan Africa and for Ghana (the focus of the Post article). The decline since the 1990s is striking and highly positive. The debate can now be about how to develop, not how to manage debt.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:21 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 23, 2008

parents' perspective

Click here if you'd like to listen to me being interviewed by Sandra Bert and Linda Perlis for their syndicated radio show, Parents' Perspective. I'm talking about my book The Future of Democracy, which is about raising active citizens, and what that means for parents.

Posted by peterlevine at 3:41 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 22, 2008

on leaving DC

We're getting ready to move CIRCLE to Tufts University on July 1 (as previously announced), and that means a move for my family as well. I've lived in DC since 1992; my wife, somewhat longer. I'm not sure that I would claim that DC is an objectively better place than others, but one develops a deep fondness for a city where one lives for a long time and experiences whole stages of life. I was a young single guy here, learning about the work world. I was married here and had children here. I've received joyous and tragic news here. The parts of the city where I have spent lots of time are not very extensive. Within those areas, I can recall specific events that took place on virtually every block, sometimes in six or seven buildings within a single block.

I've been writing here about "DC," not "Washington." The latter is the capital of the United States, the diplomatic, political, and media center. The former is a large city in the mid-Atlantic region with a fairly stable population and a distinctive local culture. This distinction is not simply one of class or income. You can be a poorly-paid environmental lobbyist and belong to "Washington," or a successful restauranteur or real-estate lawyer who is very much part of "DC." Nor is the distinction simply one of race. "DC" is predominantly Black, and Washington is predominantly White; but they are both quite diverse. It's a subtle distinction with blurred borders, which one can observe at Redskins games, firework celebrations on the Mall, and the downtown department stores. But there is a difference, and it's mainly DC that I will miss rather than Washington. I'll miss the brick townhouses with cornices and pyramidal roofs, seafood from the Bay, the accents of both African American and white natives, settings from George Pelicanos' novels, the Post Style Section, Pollo Compero, and Metro drivers who announce "Joodicuary Square." As a yuppie who came to town to work for a political organization, I can't say I'm really of DC. But as a member of a DC public school family and a commuter who has spent 90 minutes every day on the Metro for the past 15 years, I can say that I have some DC in me. And I don't think I'll shake it off.

Posted by peterlevine at 4:26 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

May 21, 2008

explaining a lack of principle

Recently, and by coincidence, I have twice heard Mickey Edwards talk about his new book, Reclaiming Conservatism: How a Great American Political Movement Got Lost--And How It Can Find Its Way Back. Edwards was a member of Congress for 16 years, during which time he served on the powerful Appropriations Committee and chaired the House Republican Policy Committee. In those years, he also co-founded the conservative think tank known as the American Enterprise Institute Heritage Foundation. He was a "movement conservative" if there ever was one.

His book, however, excoriates today's Republicans for ignoring constitutional limits on the power of government. I have not read the book, but Mr. Edwards argues in public that the problem is basically moral. It is the duty of the legislative branch to preserve and uphold the Constitution and to check the power of the president. Lately, Republican members of Congress have abandoned both roles because they have identified more with their party than with their institution. Edwards is especially outraged by presidential signing statements and violations of the FISA statute, because these actions threaten the rule of law.

It is appealing when an avid member of a movement reproaches his own side on moral grounds. (At any rate, I, as an opponent of this particular movement, find this particular apostasy appealing.) But I'm not sure that Edwards' diagnosis is complete. Why do politicians sometimes put institutions and institutional self-interest ahead, and at other times heed partisan interest? It is not clear that a self-interested politician should yoke himself to either an institution or a party. It requires some explanation why a group of politicians should switch from one loyalty to another. Understanding the reason can help guide reform.

In this case, I suspect the the "party of limited government" forgot all about limits for several reasons. Party leaders have gained control of important sources of campaign money and use the cash to enforce discipline. Public opinion doesn't help; Americans are insufficiently concerned about the Constitution. But here's a third important reason: polarization. There are hardly any liberal Republicans left in Congress, and not all that many conservative Democrats. This means that strategy sessions on both sides are relatively homogeneous. It is therefore easier to fall into "group think" and a kind of team spirit in which anything that we do is good and anything that they try to do is suspect. Conservatives can easily talk themselves into the belief that liberals are not only competitors; they are enemies of the constitutional order. If the great threat to the Constitution is the other side, then beating them becomes a moral obligation, even if one has to compromise a bit on specific constitutional principles. Such reasoning may not be the cause of Republican tactics, but it is a psychologically compelling rationale; and rationales matter.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:37 AM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

May 20, 2008

why join a cause?

I have been involved in a lot of causes--mostly rather modest or marginal affairs, but ones that have mattered to me: public journalism, campaign finance reform, deliberative democracy, civilian national service, civic education, media reform, and service-learning, among others. The standard way to evaluate such causes and decide whether to join the movements that support them is to ask about their goals and their prospects of success. To be fully rational, one compares the costs and benefits of each movement's objectives with those of other movements, adjusting for the probability and difficulty of success. A rationally altruistic person joins the movement that has the best chance of achieving the most public good, based on its "cause" and its strategies.

To use an overly-technical term, this is a "teleological" way of thinking. We evaluate each movement's telos, or fundamental and permanent purpose. Friedrich Nietzsche was a great critic of teleological thought. He saw it everywhere. In a monotheistic universe, everything seems to exist for a purpose that lies in its future but was already understood in the past. Nietzsche wished to raise deep doubts about such thinking:

the cause of the origin of a thing and its eventual utility, its actual employment and place in a system of purposes, lie worlds apart; whatever exists, having somehow come into being, is again and again reinterpreted to new ends, taken over, transformed, and redirected by some power superior to it; all events in the organic world are a subduing, a becoming master, and all subduing and becoming master involves a fresh interpretation, an adaptation through which any previous "meaning" and "purpose" are necessarily obscured or even obliterated. However well one has understood the utility of any physiological organ (or of a legal institution, a social custom, a political usage, a form in art or in a religious cult), this means nothing regarding its origin ... [On the Genealogy of Morals, Walter Kaufmann's translation.]

I think that Nietzsche exaggerated. In his zeal to say that purposes do not explain everything, he claimed that they explain nothing. In the human or social world, some things do come into being for explicit purposes and then continue to serve those very purposes for the rest of their histories. But to achieve that kind of fidelity to an original conception takes discipline, in all its forms: rules, accountability measures, procedures for expelling deviant members, frequent exhortations to recall the founding mission. The kinds of movements that attract me have no such discipline. Thus they wander from their founding "causes"--naturally and inevitably.

As a result, when I consider whether to participate, I am less interested in what distinctive promise or argument the movement makes. I am more interested in what potential it has, based on the people whom it has attracted, the way they work together, and their place in the broader society. I would not say, for example, that service-learning is a better cause or objective than other educational ideas, such as deliberation, or media-creation, or studying literature. I would say that the people who gather under the banner of "service-learning" are a good group--idealistic, committed, cohesive, but also diverse. Loyalty to such a movement seems to me a reasonable basis for continuing to participate.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:30 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 19, 2008

rule of law in an emirate

Here is a sophisticated and attractive website that explains the concept of "rule of law" to Qataris, especially high school students in Qatar's schools. The sponsors include the US Department of State and the American Bar Association's Division for Public Education, on whose advisory board I serve. (Thus I acknowledge complicity.) The site says that the rule of law is "good for you and good for Qatar!"

But what is rule of law? Specifically, can you have rule of law in a country governed by an Emir?

There are at least two conceptions of rule of law, which have been called "thin" and "thick." The thin conception is deliberately narrow. Friedrich Hayek defined it thus: "Stripped of all technicalities," he wrote, it "means that government in all its actions is bound by rules fixed and announced beforehand--rules which make it possible to foresee with fair certainty how the authority will use its coercive powers in given circumstances and to plan one's individual affairs on the basis of this knowledge." No one would say that rule of law (on this definition) is a sufficient condition of justice. Rules can be "fixed and announced beforehand" and yet be evil. But Hayek argued that the rule of law was valuable in itself. Thus it might be worth while to promote it in a country like Qatar. To do so would be a public service to the Qatari people and not merely a favor to the regime.

The thin version of rule of law can accompany various forms of government. A democracy might bind itself to act only on the basis of fixed laws, but democratic majorities are often tempted to change their rules on the fly. Thus rule of law is consistent with democracy but hardly synonymous with it. Likewise, an emir or another monarch can, either by habit and preference or under a binding constitutional provision, act according to the thin conception of the rule of law. Many European monarchs used to be very rule-guided, even though they claimed divine right. The Pope acts according to rules within the domain of canon law.

In the passage quoted above, Hayek mentions only two components of a very thin theory: laws must be fixed and announced. One could add other ingredients to a thin theory, e.g., a prohibition on bills of attainder (laws that single out individuals for special treatment). That rule follows from the same Hayekian principle that governments should be predictable so that people can order their affairs accordingly. And so the thin theory grows thicker.

One can also include much more substantive components in the definition of "rule of law"--for instance, equal protection, an independent judiciary, right to a defense, or even freedom of speech and assembly. The more you build in, the less the concept seems compatible with a monarchy, especially if the monarch (as in Qatar) makes legal distinctions between his subjects and the other 80 percent of his resident population that holds foreign citizenship. If rule of law must include ingredients incompatible with monarchy, then it is not clear that we are helping Qatar by producing this website. But I write in the conditional, because I really cannot decide whether a thin concept of rule of law is valid and worthwhile.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:10 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

May 16, 2008

the ABA division of public education

Chicago: I'm here for a board meeting of the American Bar Association's Division of Public Education. With 400,000 members, the ABA is the association of lawyers in the United States; its public education division runs programs and produces materials that contribute to public understanding of the law, rights, justice, the Constitution, and similar topics. Much of the Division's work is aimed at youth. Its director, Mabel McKinney-Browning, is one of the leaders in the movement for better civic education. She is, among other things, my successor as chair of the Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools. The Division's website provides a wealth of free materials on legal issues. As a member of the Division's advisory board, I advocate for the ABA to become a political force for civic education. So far, the ABA has resolved to "urge the amendment of the No Child Left Behind Act if reauthorized, or the adoption of other legislation, to ensure that all students experience high quality civic learning . . . [that] is regularly and appropriately assessed . . . and accorded national educational priority on a par with reading and mathematics." This position is now something that the Association's lobbyists in Washington are supposed to advocate.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:02 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 15, 2008

Bernard Gill

Last Tuesday night--it is dark and rainy, and about thirty of stand beside a parking lot on what once was prairie, not far from the narrow, powerful Mississippi. We stand around a baby pine tree and a hole. Rudy Balles, director of an anti-gang program for Peace Jam, holds a piece of braided sweetgrass that he has set alight. He moves slowly around the circle, blowing the smoke onto each of us with an object--I wish I knew its name--made mainly of feathers. The smoke carries our prayers to the Creator. Rudy sings in his deep resonant voice a song from the American Indian Movement. He sings about us and about the land, about peace and justice, and about G. Bernard Gill.

Bernard was a preacher, a leader of the National Youth Leadership Council, a widowed father of four beautiful and successful children, a young African American man of enormous achievement and promise. Right in the middle of the last NYLC Conference, which he had helped to organize, Bernard suddenly died. He told Rudy that he needed to find a cup of water, but he never came back with it. His second child was headed to college; Bernard himself was starting on a PhD. He was a model of passion, compassion, commitment, and ethics. We planted the tree for him, and you can help his family. May his name be a blessing for all who knew him.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:36 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 14, 2008

quote of the day

"If youth is the season of hope, it is often so only in the sense that our elders are hopeful about us; for no age is so apt as youth to think its emotions, partings, and resolves are the last of their kind. Each crisis seems final, simply because it is new. We are told that the oldest inhabitants of Peru do not cease to be agitated by the earthquakes, but they probably see beyond each shock, and reflect that there are plenty more still to come." -- George Eliot, Middlemarch.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:46 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 13, 2008

the payoff of "diversity"

I'm at a retreat center in the rural Midwest, with representatives of about 40 other organizations. As part of the retreat, we heard from an excellent provider of diversity training. He noted that most such trainings are actually counterproductive. They just make people feel defensive and uncomfortable. The session today emphasized the positive effects of having a more racially and ethnically diverse workforce--as a path to better products, lower turnover, and more satisfied clients.

I agree that there's much to be gained by demonstrating the economic advantages of diversity to businesses (and the educational advantages of diversity to universities). At the very least, it reduces their sense that diversity would hurt their bottom line. But we do need to keep our eyes on the issue of "distributional justice." We must ask who gets valuable opportunities and--specifically--whether African Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans are getting fair shares. It's an empirical question whether we can achieve distributional justice by emphasizing the benefits of racial and ethnic diversity to organizations. That strategy has the great advantage of being persuasive and appealing to powerful institutions. But it's possible for firms and universities to buy "diverse" workforces without doing anything to address the disadvantages of being born in lower-income minority communities in the US. So I support arguing that diversity helps the bottom line, but only if that's fully true and it advances our fundamental moral objective, which is equality of opportunity.

Posted by peterlevine at 5:42 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 12, 2008

a widening gap

A wide gap has opened between the half of young Americans who attend college and the other half who do not. I am particularly concerned about the gap in political and civic participation. Those who express their views and cast their votes get more attention from government. Voting also correlates with other forms of civic engagement, such as following the news, joining organizations, and volunteering. When young people are not engaged in these ways, society misses their contributions: their ideas, energy, and social networks. And engaging in these ways is good for young people themselves: it provides information, networks, opportunities, motivation, and support. Those who volunteer are substantially better off than those who do not. A dramatic example is the finding that belonging to voluntary associations in Chicago is associated with lower death rates, especially for African American men.*

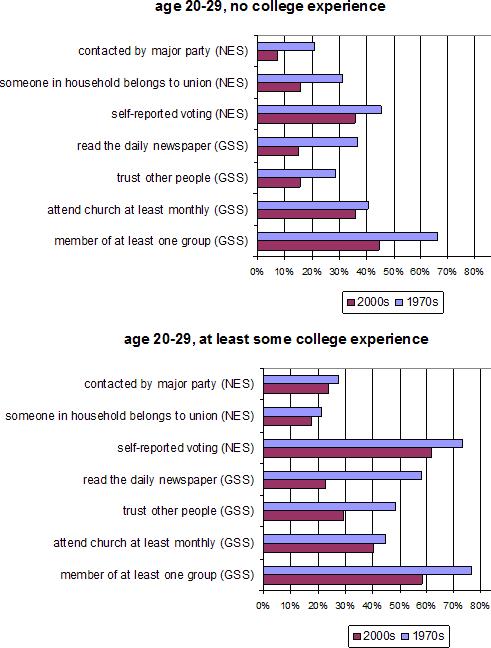

The following two graphs show the prevalence of civic engagement for young Americans during the 1970s and during the current decade. The first graph shows only young Americans without college experience; the second shows the ones who have attended at least some college.

Comparing the two graphs shows that youth on a college track are far more engaged. Engagement has declined in both groups over time; but proportionally, the change among non-college youth is much greater. While their voting rate has fallen significantly, their rates of union membership, newspaper readership, and contact by major political parties have been cut by more--at least by half. (I include trust in other people because it correlates with membership in groups and social networks.)

*See Kimberly A. Lochner, Ichiro Kawachia, Robert T. Brennan and Stephen L. Bukac, Social capital and neighborhood mortality rates in Chicago, Social Science & Medicine, vol. 56, issue 8 (April 2003), pp. 1797-1805

Posted by peterlevine at 10:56 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 9, 2008

the effects of Obama's organization

Senator Obama has 1.5 million donors, countless volunteers, a massive email list, and additional layers of organization, such as his trained "organizing fellows." What does this mean for the future of politics and government?

Matt Stoller argues that Obama will have tremendous power within the Democratic Party. His supporters are even deliberately trying to de-fund alternative sources of power, such as America Votes.

Marc Ambinder reports that the Obama campaign is going to organize "more than a million donors and volunteers to directly persuade their neighbors through a variety of media" during the campaign, thereby bypassing the news media.

And Steve Teles and I argue that Obama has a chance to pass major legislation, such as health care reform, if he uses his organized base as a grassroots lobbying force after the election. We wrote this when the argument was Obama vs. Clinton. Our idea was that Obama would have a better chance to pass legislation because of his organizing campaign. Now the contrast with Clinton seems moot (to me), but the prospect of massive grassroots lobbying remains interesting. Power over the party, the media, and Congress--that is something to think about.

Posted by peterlevine at 5:35 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 8, 2008

the power of experimentation

Today's World Bank's meeting on community service programs turned out to be mainly a debate about the value of randomized, controlled experiments in evaluation. The Bank wants such evaluations (as does the US Government); many activists and proponents of youth service don't want to do them. I am also thinking right now about randomized experiments because I will soon play a role in running one in Florida schools.

Experiments don't work for all purposes; they are not always practical; and they're not the only legitimate methods.

I did, however, share a positive example of how experiments can be very helpful--in getting out the vote. There were no experiments with voter turnout in the United States for 50 years. That's surprising because voting is a very simple, measurable act that's well suited to experimentation. In the mid-1990s, some academics and foundations started pressing the nonpartisan voter turnout groups to use randomized evaluations. The pressure at first seemed unreasonable and even arrogant. It seemed as if the experts wanted randomization for the sake of it.

But now the nonpartisan voting groups are avid experimenters. They are always looking to randomize treatments and investigate the differences in results. When they send out mailings, they design two or more messages and randomize their lists. When they work in a limited number of sites or communities, they choose the sites randomly and reserve others as a control group. They do this even when they are not pressured by funders.

I think there are three major reasons for this "culture of experimentation":

1. Randomized experimentation is a simple, transparent process. It does not involve elaborate mathematics, which you do need for statistical models. Thus the grassroots groups control their own evaluations. They don't have to trust outside experts. Experimentation is actually non-technocratic.

2. Random experiments yield useful and counter-intuitive results. For example, going door-to-door is cost-effective even though it costs quite a lot of money per contact. Emails are not cost-effective even though they are cheap. This is good to know.

3. Experimental results can persuade powerful people who are predisposed to be skeptical. The American political parties traditionally assumed that it was a waste of money to mobilize young people. In the 1990s, political consultants often deliberately stripped young people from contact lists to save resources. But the experimental evidence showed that young people would vote if contacted. That led to much more partisan investment in youth turnout. The Obama campaign even has a youth director who comes straight out of the youth voting community in which the experiments were conducted from 1998-2006. Regardless of the experimental data, Obama probably would have campaigned to youth, because he has an appeal with the new generation. Still, it doesn't seem a complete coincidence that (a) we learn how to mobilize young voters by experimenting, and (b) a candidate captures the Democratic nomination by mobilizing youth.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:47 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 7, 2008

when is political participation good for the participants?

I'm speaking tomorrow at the World Bank, which has some interest nowadays in the link between civic engagement and youth development. Basically, the idea is that investing in opportunities such as community service will benefit young people around the world, helping them to stay in school, avoid crime and disease, and generally flourish.

We know, indeed, that there are strong positive correlations between service and flourishing for Americans of all ages. Young people who volunteer do better in school; old people are less depressed. To some extent, success may cause volunteering. If you have more money and time, if you're associated with better institutions, and if you have more confidence and initiative, you are more likely to conduct activities that we call "volunteering" or "service." For instance, a full-time, white-collar worker may "volunteer" as part of an annual office outing, whereas a homeless person is unlikely to do something that would be called "volunteering" (although he might help his peers).

To an important extent, the reverse is true as well: volunteering contributes to flourishing. We know this from fairly careful studies, including studies of mandatory service (which avoid the problem that volunteers may be self-selected).

But this is the issue I'd like to raise at the World Bank: "volunteering" does not exhaust civic engagement. Citizens who want to change the world for the better may reasonably select other strategies, including voting, protest, building organizations, convening meetings, or even the age-old tactic of the oppressed, non-compliance. I often cite an example from a CIRCLE Working Paper by Michelle Charles. African American youth in Philadelphia are supposed to be cleaning up graffiti under the direction of middle-class adults. They are dragging their feet, presumably because they think this particular activity is pointless. To me, their service is not civic engagement, but their foot-dragging is. It may have the affect of ending the program, which will be positive social change.

These other forms of civic engagement are not correlated with prosperity and health. Protest, for example, is much more common among Latino and immigrant American youth than among White Anglo youth. That doesn't mean that protest is bad for individual human development. I don't think we know enough about its developmental effects (notwithstanding some important studies of 1960s activists). But it certainly could be the case that "volunteering" is good for social adjustment, and protest is bad for individual success, but good for society.

In other words, the strategy of encouraging youth to volunteer has a political agenda to it. Not being radical myself, I may be willing to endorse this strategy; but it's worth arguing about. Certainly, many of the globe's young people may resist the idea that they should be better accommodated to existing institutions through service.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:20 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

May 6, 2008

National Conference on Dialogue and Deliberation

The fourth National Conference on Dialogue & Deliberation, entitled "Creating Cultures of Collaboration," is scheduled for October 3-5, 2008 in Austin, Texas. These are huge gatherings of mostly practical people who organize public meetings, dialogs, and discussions. They are also opportunities to discuss deliberative democracy and civic engagement. Early registration is available through May 16th. There are openings for new sessions. Details here.

Posted by peterlevine at 1:03 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

May 5, 2008

what works in education

The federally funded program called "Reading First" recently received a poor evaluation. The American Prospect's Ezra Klein comments, "This fits into the larger pattern in education reform efforts which is that most ideas fall short of expectations. Vouchers have found themselves in a similar decline, and now they're losing support even among conservatives." Kevin Drum from Washington Monthly picks up the theme: "This is one of the reasons I don't blog much about education policy even though it's an interesting subject. For all the sturm and drang, in the end nothing really seems to matter. After a hundred years of more-or-less rigorous pedagogical research, we still don't know how to teach kids any better than we used to."

There are at least three ironies here:

1. Two major liberal bloggers take the failure of a program that conservatives love as evidence that nothing works in education. (Many comments on their blogs note this irony, as well.)

2. Many progressive educators dislike formal experiments that have control groups and quantitative outcome-measures. They associate those methods with the Bush administration, and they fear that holistic and interactive forms of education will suffer if so evaluated. However, it was because Reading First was subjected to a rigorous quantitative evaluation that we know it doesn't work.

3. Conservatives seem to love the phonics approach embodied in Reading First and distrust "whole language" methods, which involve teaching reading through literature. I can't understand why this has become a left/right issue. Evangelical Protestants should be enthusiastic about reading narratives.

Leaving ironies aside, the big issue is: What do we know about what works in education? If you want to see the results of evaluations that use randomized control groups, you can check out the Feds' What Works Clearinghouse. I think that's a worthwhile offering, but it's far from the whole story. It would not be surprising if few curricular packages--off-the-shelf, shrink-wrapped programs--made a big difference to kids. After all, education is mostly about relationships: between teachers and their classes, among students, between teachers and parents, and between teachers and administrators. We know that some teachers consistently produce better results than others, holding other factors constant. That's partly because their relationships are better. (They're not necessarily nicer or friendlier, but they are more effective at working with children and other adults in their contexts.) We also know that the level of community participation in schools makes a difference. These factors matter, but they are hard to influence through national policy.

Certainly, any parent knows that some schools are better than others, and some teachers are better than others; and it's not just because of money or demographics. That means that some things work in education. Yet simple mandates and programs are unlikely to make schools better, because they don't influence relationships. And formal experiments that evaluate programs are most likely to show disappointing results.

Posted by peterlevine at 4:47 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

May 2, 2008

nothing new

The sorting of students into colleges and the marketing of colleges to prospective applicants sometimes seems a corrupt business, a marketplace in which prestige is sold to the highest bidder. It's a domain of glitzy advertising, coaches and test-prep services, rankings, scouts, and networking. At least none of this is completely new. In 1506, the principal of an Oxford college called Staple Hall allegedly promised six shillings and eight pence (6s 8d) to a man who would introduce him to the Bishop of LLandaff so that he might persuade said Bishop to send a boy of his household to Staple Hall. A ward of a bishop was a good prospect to donate money after graduating. The principal allegedly failed to pay the promised 6s 8d, leading to a suit whose outcome I don't know, but whose proceedings would probably seem perfectly familiar half a millennium later.

(Perhaps justice caught up with the principal of Staple Hall, for not long afterwards, his institution lay in "ruynes." Around 1570, William Lambarde wrote about the halls of Oxford: "I have hearde that theare hathe been dyvers others of this kinde, and it seemeth true by the ruynes that yet appear in syghte. I redd in a case that theare was some tyme a house of learninge called Staple Hall; but where it stoade, I have not hytherto learned.")

Sources: W.A. Pantin, Oxford Life in Oxford Archives, 1972, p. 6; John Alan Giles, History of Witney, 1852, p. 46.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:40 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack