« March 2006 | Main | May 2006 »

April 27, 2006

the "common good"

(Wisconsin) Thanks to regular reader Joe Sinatra, I recently read an article in which Michael Tomasky argued that the Democrats should use the language of "the common good" instead of emphasizing rights for various groups. David Brooks then did Tomasky no favor by endorsing his view in the New York Times and making him sound like a scathing critic of a caricatured version of "identity politics" (which he isn't).

I've mainly considered the rhetoric of the "common good" in connection with the Progressive Movement. In 1900-1924, the original Progressives assumed that "the moral and the general were synonymous, and that which was unworthy [was] the private, the partial, interest."* It was on this basis that they fought various forms of corruption and expanded the powers of the central state over the market. Appeals to the "common good" and "public interest" have been made at other times and from other points on the ideological spectrum. However, the Progressives contrasted the common good against special or private interests with striking consistency and fervor.

Mainstream liberalism since the 1960s has been quite different. I don't endorse simplistic accounts of identity politics, but surely modern American liberals have been suspicious of the common good and more concerned about rights for distinct groups. Why?

1. In practice, the "common good" can mean the interests of the median voter, who (depending on how one describes the electorate) may turn out to be a white, working-class guy from the Midwest. That's precisely the constituency that Brooks thinks the Democrats have lost by courting minorities, gays, immigrants, women, and so on. However, white, working-class guys from the Midwest are just one group with interests of its own. Liberals don't want to identify those interests with the common good, even if doing so would help win elections. It wouldn't be fair.

2. The phrase "common good" can be vacuous--available to anyone, and equivalent to saying that one's positions are right or good. For instance, people claim the mantle of the "common good" in arguing that wealth should be redistributed, or that individual economic freedom should prevail. Some equate the common good with private liberty; others claim that it means improving public morality. Maybe it means nothing at all.

Nevertheless, I'm not sure that Tomasky is wrong. Talking about the common good has several advantages.

First, it's explicitly moral language, and that's good for liberals. It forces the speaker to justify his or her proposals in terms of universal principles: to show why, for example, a tax break or a federal program is fair for all. It provokes deliberation.

If people think of government as a device for helping them individually, many will prefer market mechanisms and private choice. That's especially true when the median income is pretty high, as it is in the USA; then many voters don't believe that the government (seen as a service-provider) offers a particularly good deal. Citizens are more likely to favor government if they believe that it has idealistic purposes and offers them a chance to deliberate and participate in high-minded ways. The language of duty to a common good can be motivating--and for morally legitimate reasons. Tomasky: "This is the only justification leaders can make to citizens for liberal governance, really: That all are being asked to contribute to a project larger than themselves."

Second, talk of "the common good" makes us think of genuinely common assets and the need to preserve them. Thus we will focus on un-owned goods, such as the ozone layer, the oceans, our cultural heritage, scientific knowledge, and the Internet.

Third, this language draws attention to problems with our political procedures and our political culture. I think Rousseau was the first to note that people tend to disagree about concrete issues but can often reach consensus about procedures and norms. Thus political leaders who invoke the "common good" naturally think of procedural reforms, such as anti-curruption measures, tax-simplification, transparency, and rule-of-law: causes that can attract broad popular consensus. Progressive leaders (such as Wilson, TR, and La Follette) were often vague about how to address specific economic and cultural disputes, but passionate about matters like campaign-finance reform, lobby regulation, direct election of senators, and women's suffrage.

Why would it be good to emphasize procedural reforms today? Because there are serious problems with our current political procedures and political culture that have to be fixed before we can get better policies.

*"Otis L. Graham, Jr., An Encore for Reform: The Old Progressives and the New Deal (New York, 1967), p. 70O.

Posted by peterlevine at 2:51 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

social change from an individual's perspective

(On a flight to Milwaukee): At a meeting earlier this week, experts and advocates debated data on the civic participation of particular disadvantaged groups. The groups we were talking about don't vote or volunteer, according to surveys conducted by the Census Bureau and other authorities. A crucial question arose: Do we believe that voting and volunteering rates measure worthwhile forms of behavior? Why don't we measure, for example, business deals that build the strength of an ethnic community? Or the kind of deliberate foot-dragging and noncompliance that is often the resort of poor people when faced with oppressive power?

It occurred to me that we don't have theories that tell us how an individual should act to cause social change. There are plenty of theories that try to explain when and why social change occurs, e.g., because of revolutions in the means of production, technological innovations, shifts in demographics and geographical distribution, crises of rising expectations, failures of the prevailing ideology to match reality .... But there are not many theories about what you or I should do if we have political goals. The standard theories sometimes even suggest that you and I can do nothing, because social change is not influenced by deliberate human action--but that view is surely overstated. I may be missing useful theories, but all I can think of are nostrums about the power of small-scale collective action, by the likes of Margaret Mead, Einstein, Gandhi, and Martin Luther King. I find their advice more inspirational than analytical.

If there were a true academic discipline of citizenship, one of its main questions would be: What are the best strategies for obtaining social change if you are an individual situated in various ways? That would be quite different from a more standard question in political science, which is: Why do institutions and policies change? If we could answer the first question, then we could say much more about the kinds of civic engagement that are most valuable for people in various situations. That would be much better than the standard approach right now, which is simply to use the available data to measure "participation," as if it were self-evident that voting and volunteering are effective.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:03 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

April 26, 2006

more on teaching patriotism

On Crooked Timber, Harry Brighouse has replied to my previous post about patriotism in schools. He is skeptical, mainly on the (reasonable) ground that patriotism causes or excuses partiality toward one's fellow citizens, and such partiality is particularly problematic when one's nation happens to be very rich and powerful. Harry's post prompted several substantive replies: a good discussion in the Crooked Timber comment field. I'd only add that I feel somewhat awkward defending patriotic education in schools. I still think the arguments in favor outweigh those against, so I'm not ready to strike my flag (so to speak). However, instilling patriotic sentiments is far from the center of my own work and concerns. Apart from anything else, there is no evidence that young people lack patriotism, whereas there is plenty of reason to fear that they lack the confidence, skills, and interests necessary to be effective participants in democracy.

Posted by peterlevine at 1:51 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 25, 2006

what should we get for $44 billion?

(New York City) The director of national intelligence, John D. Negroponte, recently disclosed that 100,000 people work for the US intelligence agencies. Not long before that disclosure, his deputy, Mary Margaret Graham, let slip that the intelligence budget of the United States is $44 billion.

I'm in favor of getting good intelligence, but those numbers look huge when put in context. The total cost of research in American degree-granting universities was $18 billion in 2000-2001. That figure excluded overhead (the cost of libraries, cafeterias, heating bills, etc). Furthermore, academic research is more expensive in 2006 than it was five years ago. Nevertheless, it appears that the intelligence agencies of the US spend more than the cost of research in all 4,236 American institutions of higher education put together.

I realize that intelligence is more expensive than some other forms of research, because some of the data must be collected against foreign countries' will--which requires spy satellites, bugs, and bribes. But colleges and universities study a huge range of subjects (from global warming to ancient Sumerian) for a total that is smaller than what the US government spends to investigate foreign states and organizations.

A tiny proportion of academic research goes, for example, to studying modern Iraq. But is there any doubt that the academic experts on Iraq better predicted the results of an invasion than the $44-billion intelligence agencies? The same agencies utterly misunderstood the course of events in Czechoslovakia in 1968, the Middle East in 1973, Iran in 1979, the Soviet Union in the 1980s, Pakistan since 2000, and the Palestinian territories in the recent elections.

As libertarians and free-market conservatives should be the first to suspect, a monopolistic, bureaucratic, closed system of intelligence gathering is unlikely to be anything other than inefficient and incompetent. It may amass piles of secret data (to justify enormous budgets and to give it access to information that no one else has), but it will fail to interpret, synthesize, or predict. The late Senator Moynihan once wrote that during the Cold War, "error became a distinctive feature of the [national security] system. This is easy enough to explain. As everything became secret, it became ever more difficult to correct mistakes. Why? Because most of the people who might spot the mistakes were kept from knowing about them because the mistakes were classified." [Moynihan, "The Peace Dividend," New York Review of Books, (June 28, 1990), p. 3.]

With this warning in mind, we read that a CIA employee or alumnus was recently "refused permission to publish an op-ed article that drew on material from the agency's Web site"; and the Agency's inspector general has been given, or has chosen to take, a lie-detector test--but he cannot publicly say why.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:00 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 24, 2006

"a concerted pushback"

(En route to Baltimore and New York City) In general, Americans are abandoning our obligation to prepare young people for active and responsible citizenship, but there was good news last week for those who want to revive civic education--which includes service opportunities, extracurricular activities, and whole-school reform as well as social studies classes.

Last Monday, as I already reported, the national advisory committee of the Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools met. C-Span broadcast speeches by its co-chairs, former Justice Sandra Day O'Connor and L.A. School Superintendent Roy Romer. The same meeting also generated a very nice syndicated column by David Broder entitled "Saving Democracy, Pupil by Pupil." Broder writes that "No Child Left Behind," the major education reform act of 2002,

was not intended to push other subjects out of the schools, but, Romer said, 'Quite often, the tests that states will use for No Child Left Behind will be only on certain core subjects, such as language arts and math and sometimes science, and school systems, if not careful, can be warped into the neglect of social studies.'O'Connor and Romer are the national spokesmen for a concerted pushback against these trends calling itself the Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools (http://www.civicmissionofschools.org/). Twenty-nine national organizations and a dozen notable private individuals have lent their support; foundation money as well is behind it.

Those 29 organizations and "notable" individuals then met on Friday for the semi-annual steering committee meeting of the Campaign, which I chaired. We approved a white paper on high school reform that we had debated and revised for more than a year. I like the final version, which the Campaign will soon release. We also discussed our position on No Child Left Behind, without (as yet) reaching agreement about what should be done.

On Thursday night, Justice O'Connor attended the annual awards dinner for Streetlaw, an organization that provides curriculum and training for civic education. In giving an award to Mrs. Cecilia Marshall (Justice Thurgood Marshall's widow), she noted her own work for the Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools and said that "civic education is very much part of my concern these days." So it must be: in addition to giving the two speeches I mentioned above, the Justice also met privately with David Broder and chaired a meeting of the American Bar Association's committee on civic education--all in one week.

I had the honor of giving Streetlaw's Educator Award to an excellent high school teacher from Brooklyn, Patrick McGillicuddy. He has achieved remarkable success in a school reserved for students who have dropped out or been expelled from other institutions. He teaches the whole of American history as a series of mock trials. The kids not only have fun and learn debating skills; every one of them passes the New York State American History Regents Exam.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:45 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 21, 2006

national essence

If you've spent substantial time in a second country, you probably recognize certain qualities of everyday life that distinguish that nation from your own: for example, the smell of common cleaning products, the items on menus of cheap eateries, the uniforms of bus drivers and janitors, the cadences of conversations that you cannot quite hear, the shape of electrical outlets, the most common building materials, whether or not packs of teenage girls hold hands as they walk down the street, the layout of sidewalks, the taste of popular candy bars and soft drinks, the typography of signs, and the color of light from streetlamps.

Having been a kid in both England and upstate New York, I always felt I could recognize the essential texture of Englishness--which is most concentrated in places that tourists never go, like school lunchrooms, suburban playgrounds, and doctors' offices ("surgeries"). Lately, however, on trips to the Low Countries and Scandinavia, I have begun to wonder whether what I thought was English, or perhaps British, is actually the shared vernacular culture of Europe north of France. For instance:

1. A sandwich shop where I ate in Antwerp could have been in London, save for the language. The daily menu on the chalk board standing on the sidewalk, the food itself, the clientele--businessmen in a certain kind of suit--all could be found in Soho.

2. The snack bar outside the Viking Ship Museum in Oslo resembled innumerable such shops outside of "stately homes," public gardens, and archaeological sites in England, ca. 1980. There was something about the list of ice cream novelties, the typography of the sign, the summer sunlight at that northern latitude, and the line of expectant schoolchildren with pocket-money that I would have considered essentially British.

3. At the Nordbrabantsmuseum in 's-Hertogensbosch, the Netherlands, a reconstructed kitchen from the 1930s reminded me of similar displays in South Kensington and in provincial British museums--not only because the kitchen and its supplies looked English, but also because a certain nostalgia had caused it to be rebuilt in a museum.

I'm starting to think that there's a Northern-European vernacular that stops at the French border. Did it originate in Victorian England and spread across the north of the continent in the age of English dominance? Or does it reflect some profound commonality among the Angles, Saxons, Jutes, Frisians, and Norsemen who settled modern England?

Posted by peterlevine at 2:14 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 20, 2006

we pledge allegiance to the flags

Some people are angry about the display of Mexican flags at rallies for immigrant rights. "This isn't Mexico," said Joseph Turner, founder of Save Our State. "This is America .... What [annoys me] most is the arrogance that they are going to fly a foreign flag on my soil." But nothing could be more American. Within five minutes of searching Google images, I found the green, white, and orange tricolor flag of the Irish Republic at the head of St. Patrick's Day parades in Cape Cod and Staten Island, New York; the tricolore italiano waving at a New York City Columbus Day Parade; a profusion of Greek flags on Fifth Avenue during the National Greek Parade; and rival Israeli and Palestinian flags at an Israeli Independence Day rally at Stanford. Usually, the Stars and Stripes is carried next to foreign flags at ethnic pride parades; that was also the case at the recent immigration rallies.

Some people are angry about the display of Mexican flags at rallies for immigrant rights. "This isn't Mexico," said Joseph Turner, founder of Save Our State. "This is America .... What [annoys me] most is the arrogance that they are going to fly a foreign flag on my soil." But nothing could be more American. Within five minutes of searching Google images, I found the green, white, and orange tricolor flag of the Irish Republic at the head of St. Patrick's Day parades in Cape Cod and Staten Island, New York; the tricolore italiano waving at a New York City Columbus Day Parade; a profusion of Greek flags on Fifth Avenue during the National Greek Parade; and rival Israeli and Palestinian flags at an Israeli Independence Day rally at Stanford. Usually, the Stars and Stripes is carried next to foreign flags at ethnic pride parades; that was also the case at the recent immigration rallies.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:11 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

April 19, 2006

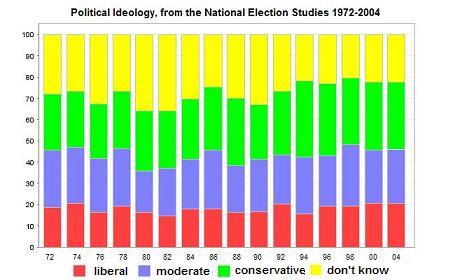

a picture is worth 1,000 words

Sometimes, when I think about the state of civic engagement in America, I just want to make a face ...

Posted by peterlevine at 9:40 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 18, 2006

on generals criticizing their bosses

A lot of us are hoping that the retired generals who are criticizing Defense Secretary Rumsfeld will prevail. That's because we think--or hope--that they have the right views about Guantanamo and Abu Ghraib, about the huge strategic mistakes that were made at the beginning of the Iraq war, about the value of changing civilian leaders right now, and about the folly of a preemptive attack on Iran. However, we don't know the full story, so we cannot tell whether they are actually on the right side of these questions. More important, in some future debate, the uniformed military could be wrong and the appointed civilians in the Pentagon could be right. So whether and when generals should criticize political leaders--a question that evidently vexes them more than anyone--should be considered as a general matter of constitutional design, and not simply in response to recent news.

I think several conflicting principles come into play:

1 Discipline. Although members of the armed forces must disobey patently illegal orders, they must obey all other orders without delay or public dissent that might undermine discipline. The rationale is that a military organization cannot be effective unless everyone does his part without trying to play commander-in-chief. One could, however, raise questions about whether that is the best organizational model in the 21st century. Further, it is unclear whether the demands of discipline apply to retired officers and to those who resign in order to dissent. Retired General John Batiste explains that he couldn't critize Rumsfeld if he were "still in uniform. ... I would be arrested." Even so, he calls his criticism "gut-wrenching, the hardest thing I have ever had to do in my life."

2. Civilian control. The armed forces have the power to govern but no legitimate right to do so. To control them, we count on constitutional rules plus a strong tradition of deference to civilian leaders. The US armed forces are proud of that deference. General Richard Myers says, "In our system, when it's all said and done . . . civilians make the decisions. And we live by those decisions." If generals publicly criticize elected or appointed leaders in a way that changes the political situation, they have challenged civilian control. That has happened many times in the past, e.g., on issues like gays in the military and the procurement of weapons systems. Still, criticizing a Secretary of Defense for his handling of an ongoing war escalates the military/civilian struggle in a way that makes some uniformed officers uncomfortable--and for good reason.

3. Professionalism. A true profession is a defined group that has a legally sanctioned monopoly on certain rights and privileges. In return, its members must follow an elaborate ethical code and both unwritten and unwritten norms. Commissioned military officers are certainly professionals in that sense. Thus, on one hand, they ought to resign and complain rather than do things that violate their professional norms. On the other hand, those norms include discipline and deference to civilian leadership (see above). On such questions as the treatment of detainees, the two aspects of military professionalism have collided.

4. Public deliberation. The ultimate source of legitimate power is not the civilian leadership but the people. We citizens have an obligation to deliberate with good information. Candid comments by retired (or serving) officers could be an excellent source of insights and advice. On the other hand, generals can abuse their credibility by providing selective accounts of secret meetings or by claiming authority on the basis of their own service records.

5. Expertise. Uniformed officers are experts on fighting wars--more so than people like Dick Cheney, who has never been on a battlefield. Expertise is valuable and deserves respect. However, deference to experts always requires several demanding assumptions: (a) they are trustworthy and speak in the national interest; (b) they are reliable and have not succumbed to group-think or closed horizons; and (c) their expertise is about the right topics. In a complex situation like the Iraq conflict, expertise in war-fighting is not enough: you also have to understand various Iraqi cultures, diplomatic processes and techniques, nation-building, economics, and so on. If military expertise dominates, bad planning can result.

6. Policy versus implementation. In rebutting the dissident generals, the administration has argued that the President and his advisors made a decision about broad policy, for which they were accountable to Congress and the voters. They decided to invade; the generals then made the plan for implementing the invasion. This is the same distinction that has been used throughout the executive branch since the 1930s. We are said to live in a democracy, even though appointed experts hold enormous power, because they merely make tactical or technical decisions about implementation, whereas elected leaders set all the strategies and goals. However, a case like the Iraq war shows that no clear lines can be drawn between strategy and tactics or between policy and implementation.

7. A record of personal sacrifice. Military officers gain a huge rhetorical advantage from having volunteered for a job that doesn't pay well, that involves hardships, and that puts them in danger. Retired General Greg Newbold has written, "My sincere view is that the commitment of our forces to this fight was done with a casualness and swagger that are the special province of those who have never had to execute these missions -- or bury the results." I find that persuasive, but then again, I agree with the substance of his comment. When generals said that Clinton was allowing gays in the military even though he had been too cowardly to serve himself, they were using their bona fides for a bad cause. We have to be careful to honor service without necessarily agreeing with everything a veteran says.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:39 AM | Comments (3) | TrackBack

April 17, 2006

from the periphery to the center

Today was the public launch of the advisory committee of the Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools. The committe's co-chairs, Justice Sandra Day O'Connor and Gov. Roy Romer (now the head of the Los Angeles public schools), spoke at the National Press Club along with Senator Harris Wofford, Judge Marjorie Rendell from Pennsylvania, and others. C-SPAN and Fox News had cameras running; I don't know whether or when the event will actually air.

Senator Harris Wofford told an amusing but telling anecdote. To paraphrase: When he ran for the Senate in 1990, his consultant, James Carville, told him that his worst fear was that Mr. Wofford would go off talking about Gandhi, service-learning, and civic education. Those topics are "out there on the periphery," Carville told his client, but no one can make them central. Indeed, Wofford famously won his Senate seat on a health-care platform. But there are ways to weave themes of active citizenship and democratic renewal into mainstream politics, I believe.

I also spoke. I'm having computer problems the last few days, but when I'm able to retrieve the file with my speech, I'll paste it here (below the fold).

Like the high school debater that I never was, I'm going to speak for a short time and try to put a lot of facts before you quckly. I will leave it to our distinguished leaders to make a more eloquent case for civic learning. However, I do believe that the facts and data tell a pretty strong story.

First of all, what is civic learning? It includes classes on civics, government or history. Data show that these courses significantly increase students’ knowledge and skills: for example, the skill of interpreting news articles and speeches. As we said in the Civic Mission of Schools report, "if you teach them, they will learn."

Courses probably enhance students’ behavior as well as their knowledge. In a poll that the Campaign sponsored along with several partners, young people who had taken a civics class were twice as likely to vote, twice as likely to follow the news, and four times more likely to volunteer for a campaign than those who had never taken civics courses. That doesn't mean that a single course doubles voter turnout; the relationship is a bit more complicated than that. But the most careful analysis suggests that courses have significant effects on students' behavior. And courses certainly boost knowledge and skills.

In short, courses are valuable, but civic learning means more than courses.

It also includes extracurricular activities, such as student government, school newspapers, and other organizations that give kids experience in working together, addressing problems, and managing voluntary groups. A very careful study that has followed the high school class of 1965 right up to the present finds that participating in extracurriculars increased kids’ civic engagement when they were young, and the difference is still evident in their behavior now—forty years after they graduated. No program has ever been found that has nearly as much effect on adults' participation in civil society. If we want to revive America's communities, restoring high school extracurriculars looks like one of the very best strategies.

Community service is another element of civic learning. When service is connected to academic study, we call it "service-learning." Careful studies show that high-quality service-learning enhances civic values and habits of service and sometimes changes kids’ fundamental identities so that they see themselves as active citizens, even years later. Again, no program for adults has been shown to have that kind of impact on identities. We have our best shot at enhancing volunteerism if we give people opportunities to serve while they are young.

Kids also learn by discussing current events. Discussion boost knowledge and interest, especially when students feel that the conversation is genuinely open to diverse perspectives. It’s especially valuable for kids to use and discuss the news media, and even to create their own newspapers, broadcast news shows, and news-oriented websites.

If a school is organized as a true community in which students feel they belong and can play a constructive role, that too is a form of "civic learning" that is proven to have positive effects on students’ skills and interests.

Students can also learn through simulations, such as moot courts, model UN, and (nowadays) elaborate computer games that are designed for educational purposes.

If anyone's been counting, you'll notice that I have listed six "promising practices" for civic learning. Students need a rich combination of all six practices.

Unfortunately, civic education is in decline, which is why our movement has been launched and has attracted such distinguished supporters.

Perhaps the clearest drop is in extracurricular activities. Leaving out sports, the rate of participation in school clubs appears to have fallen by half since the 1960s.

In the last three years, the No Child Left Behind Act has shrunk the whole social studies curriculum, including American history and American government courses, which had been pretty resilient until recently. The Center for Education Progress recently found that 71% of school districts had cut back time on other subjects to make more space for reading and math. History, Geography and Civics were the most heavily cut areas of the curriculum.

Finally, I would like to note that civic education is especially important for disadvantaged kids, although unfortunately they get less of it. According to a big federal study in 1998, students of color and students from low-education families were the least likely to experience interactive social studies lessons that included role-playing exercises, mock trials, visits from community members, and letter writing.

After 1970, we lost two courses from the standard curriculum: 9th-grade "civics" (which used to teach about the role of citizens in their communities) and "problems of democracy" (which involved discussions of current events). What was left was 12th grade American government and some advanced courses on social sciences. Those are useful classes, but many students drop out before they can take them. We know that one third of all youth and half of African American and Latino adolescents do not finish high school.

The result of these disparities in opportunities is evident when you look at outcomes. High school dropouts are much less engaged in their communities and in politics than people who completed high school. And the disparities start early. If one compares two groups of 14-year-olds—one group has highly educated parents and many books in the home and intends to attend college, and the other group lacks those advantages—the better-off group already displays far more political knowledge and is three times more likely to expect to vote.

I hope this brief summary of research helps make the case that civic learning--defined with appropriate breadth--is a powerful way to enhance American democracy and that we need to do it better.

Posted by peterlevine at 1:06 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 14, 2006

more discussion of school policy

Harry Brighouse at Crooked Timber has written a response to my recent post on "major strategies for educational reform." There are a few interesting comments on the Crooked Timber page. I was struck by one person's claim: "The difficulty with looking within schools is that in my experience you need a hell of a lot of experience to understand an industry/system/sector from within. And by that I mean any industry, not just education." I'd respond that education shouldn't be viewed as a "sector," but rather as a highly normative (i.e., value-laden) activity of a whole community, including, but not limited to, what goes on in schools. Education is the process by which we replicate--and possibly enhance--our culture. If we convince ourselves that schools form a complex specialized system that we lack the expertise to understand or reform, then we abandon a crucial opportunity to shape our future.

Incidentally, I met last week with the social-science education director of a smallish European country. He had just completed an elaborate set of consultations to develop a national curriculum for "civics." The curriculum itself sounded very good to me. The process was deliberative and is overseen (at least in principle) by a democratically elected parliament. Now that decisions have been made, every school and teacher-training program in the country (secular or religious) must implement the curriculum. Inspectors will visit classrooms regularly to check on compliance. Apparently, they inspect Moslem schools monthly because they do not trust them to present the national constitution fairly.

This is one version of democratic education. The purpose of the civics curriculum is democratic; the methods and topics seem likely to produce democratic skills and attitudes; and the national agency responsible for the whole business is transparent and accountable to the voters. In contrast, democratic education in the US is ad hoc, uneven, and generally in decline. However, the European approach is not "community based," participatory, or pluralist. I was left thinking about the tradeoffs.

Posted by peterlevine at 3:07 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

April 13, 2006

privatizing the neighborhood

My colleague Bob Nelson has an article in Reason that's derived from his book, Private Neighborhoods and the Transformation of Local Government. Nelson makes proposals that will appeal to Reason's core audience of libertarians; but they could also attract some lefties.

Today, local governments are creatures of the states, assigned exclusive duties and powers over a defined geographical area. Originally, Nelson argues, municipalities were corporations that formed as voluntary associations and held many of the rights we now associate with businesses: the rights to merge or divide, to purchase other entities, to contract out particular services, and to buy or sell property rights.

Nelson thinks that governmental entities should be granted similar flexibility. Then neighborhoods could secede to satisfy their residents better, or governments could unite to gain economies of scale. The two things could happen simultaneously. For example, neighboring governments could sell their transportation functions (including eminent domain) to a regional entity that would provide economies of scale, but turn their schools over to small nonprofit corporations at the neighborhood level.

Districts could even sell themselves wholesale. For example, residents of the Sursum Corda housing project in Washington, when granted collective property rights over their whole facility, sold it for $80,000 per unit, plus the rights to buy apartments at a discount in the new building constructed where theirs had been.

Lefties should be interested in Nelson's idea because poor urban neighborhoods would gain economic benefits and opportunities for participatory self-government--opportunities that they are denied within big cities. Nelson's proposal has much in common with the various forms of "democratic, community wealth-building institutions" that my progressive colleagues, Gar Alperovitz and his allies, advocate.

My main concern has to do with the effects of secession. The Sursum Corda residents got (and deserved to get) a good deal when the land where they lived appreciated rapidly thanks to the opening of a new Metro station. But most poor urban neighborhoods don't have a whole lot to offer on the market. Meanwhile, I can imagine my own Washington neighborhood deciding to handle local services, including education, by itself. The median income in our yuppie area is so high that tax rates could be set very low and there would still be plenty of cash for trash removal and police. Many families use private schools already. Others send their kids to public schools only if they believe that the percentage of "out-of-bounds" students is low. They would love to keep the neighborhood school for yuppie neighbors only. The result would be a lot less redistribution to other parts of the city.

That said, many of the services that our DC taxes provide are of bad quality. More affluent parts of the city still receive much better services than poor ones. And middle-class families still move across the state line to avoid redistribution. So perhaps radical decentralization would work better.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:14 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 12, 2006

Judas, priest

I don't know much about gnosticism, but it's interesting to compare the newly translated gnostic "Gospel of Judas" with the four canonical gospels as works of literature. The contrast that jumps out at everyone concerns plot and characterization: Judas is the hero, rather than the villain, in the document named after him. But I was interested that Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John have literary merits far in excess of "Judas." Perhaps this was one reason they prevailed in the early centuries of Christianity.

1. Point of view

In the canonical gospels, it's easy to identify with the apostles. Jesus is a partially mysterious figure, but his followers are very recognizable human beings. For example, Peter's denial of Jesus (Matthew 26:74-75) is one of the most vivid descriptions of the internal state of a flawed person ever written in antiquity, as Erich Auerbach argued in his book Mimesis.

In parts of the canonical Gospels, the apostles are distinguished from everyone else because Jesus shares secrets with them alone: "Unto you it is given to know the mystery of the kingdom of God: but unto them that are without, all these things are done in parables: That seeing they may see, and not perceive; and hearing they may hear, and not understand; lest at any time they should be converted, and their sins should be forgiven them" (Mark 4:11-12). It appears that the purpose of Jesus' secrecy is to deny the multitude knowledge that would save them.* However, we readers have full access to what the twelve apostles learn in private, so we can fully understand the parable. We naturally identify with the disciples and not with the multitude. John ends his Gospel: "these are written, that ye might believe ... and that believing ye might have life."

In contrast, it's impossible to identify with Judas in his eponymous gnostic gospel. Jesus asks whether anyone has the strength to bring the "perfect human" out from within him, and apparently Judas does. He and the other apostles also receive remarkable visions--among others, a vision of themselves as temple-priests who commit various sins. They know things about "Barbelo" and other exotic realms. In all these respects, they are unlike us. It is very difficult to identify with them as they receive Jesus' gnostic message--which (in any case) remains cryptic even after he explains it to them.

2. the dramatis personae

In the canonical gospels, virtually every character is a realistically depicted human being. God is abstract and universal, but God does not speak or appear in the gospels themselves. There are some angels, but they act roughly like human beings and understand the emotions of their human interlocutors. (Said the angel, "Fear not, Zacharias ...") When Jesus appears transfigured in a shining raiment, it is a powerful image because we have come to know him as a regular human being, starting as a baby.

In contrast, there are multitudes of non-human characters in the Gospel of Judas: for instance, the seventy-two luminaries, who themselves make another 360 "luminaries appear in the incorruptible generation." There are also various supernatural beings with names like Yaldaboath and Saklas. It is impossible to visualize these figures in any concrete form. Even Jesus is introduced with a phrase that suggests he didn't appear or behave like a regular mortal: "Often he did not appear to his disciples as humself, but was found among them as a child."

3. Laughter

Famously, Jesus does not laugh in the canonical Bible, although he is laughed at to scorn. In the short text of "Judas," he laughs three times--in fact, it is his characteristic way of opening a dialogue with the apostles. His laugh is mirthless, a scornful dismissal of sinners.

*This is the passage (the Parable of the Sower) in which Jesus describes some seed that falls on a rock where it cannot put down roots. Likewise, in "Judas," Jesus explains: "It is impossible to sow seed on [rock] and harvest its fruit." The Parable of the Sower must have had special interest for the Gnostics, because it explains why a few are chosen and the rest are ignorant. Note that while Mark says, "these things are done in parables ... that [hina] they may ... not perceive," Matthew softens it to: "Therefore speak I to them in parables: because [hoti] they seeing see not; and hearing they hear not, neither do they understand" (Matt 13:13). In Matthew, the Parable is a technique for enlightening the ignorant; in Mark, it is a way of keeping them so.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:06 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 11, 2006

should we teach patriotism?

I suspect that most Americans want schools to teach patriotism. However, experts on education are, for the most part, leery of this goal. In a CIRCLE working paper (pdf), William Damon writes:

The final, and most serious, problem that I will mention has to do with the capacity for positive feelings towards one society, with a sense of attachment, a sense of affiliation, a sense of purpose fostered by one's role as citizen. This is an emotional capacity that, since the time of the ancient Greeks, has been known as patriotism. This is not a familiar word in most educational circles. In fact, I would guess that patriotism is the most politically-incorrect word in education today. If you think it's hard to talk about morality and values in schools, try talking about patriotism. You really can't get away with it without provoking an argument or, at the least, a curt change of subject. Teachers too often confuse a patriotic love of country with the kind of militaristic chauvinism that 20th Century dictators used to justify warfare and manipulate their own masses. They do not seem to realize that it was the patriotic resistance to these dictatorships, by citizens of democratic republics such as our own, that saved the world from tyranny in the past century and is the best hope of doing so in the future.

Along similar lines, Harry Brighouse quotes a British official, Nick Tate, who complains about his experience on a UK curriculum committee: "There was such a widespread association between national identity, patriotism, xenophobia, and racism that it was impossible to talk about the first two without being accused of the rest." The Civic Mission of Schools report (a consensus statement that I helped to organize) does not use the word "patriotism."

The question can be divided into two parts: Is patriotism a desirable attitude? Is it an attitude that should be promoted by public schools? I would answer both questions with a qualified yes.

Patriotism is love of country. For most people, it is not a passionate and exclusive and life-altering love. It's more like love for a blood-relative, perhaps an aunt. It doesn't involve choice. It doesn't require a tremendously high estimate of the object's intrinsic qualities. (You may admire Mother Theresa more than your Aunt Theresa, but it is the latter you love.) It implies a sense of obligation, including an obligation to understand and be interested in the object. It also implies a sense of entitlement: you can expect your own aunt, or your nation, to help you in ways that others need not. Both the obligation and the entitlement arise because of a sense of identification, a "we-ness," a seeing of yourself in the object and vice-versa.

I think that people should love large human communities in this way. You may put your family first, but to love only them is too exclusive. Loving all of humankind is good, but it doesn't mean the same thing as love for a concrete object. For instance, you cannot have an obligation to know many details about humankind.

A nation works as an object of love. One can identify with it and feel consequent obligations and entitlements, including the obligation to know its history, culture, constitution, and geography. Love for a country inspires, enlarges one's sympathies, and gives one a sense of support and solidarity. I would not claim that these moral advantages follow only from loving a country. One can also love world Jewry, one's city, or one's fellow Rotarians. But love of country has some particular advantages:

1. Patriotism promotes participation in national politics, including such acts as voting, joining national social movements, litigating in federal court, and enlisting in the military or serving in the civil service. In turn, broad participation makes national politics work better and more justly. And national politics is important, because national institutions have supremacy. A system that devolved more power to localities would need less national participation, and hence less patriotism. But it would have its own disadvantages.

2. Patriotism is a flexible concept, subject to fruitful debate. Consider what love of America meant for Woody Guthrie, Francis Bellamy (the Christian socialist author of the Pledge of Allegiance), Frederick Douglass (author of a great 1852 Independence Day speech), Nathan Hale, Presidents Lincoln and Reagan, J. Edgar Hoover, Saul Bellow, or Richard Rorty. All these men believed that they could make effective political arguments by citing--and redefining--patriotic sentiments. One could argue that their rhetoric obfuscated: they should have defended their core values without mixing in patriotic sentiments. Brighouse complains (p. 105) that patriotism can be "used to interrupt the flow of free and rational political debate within a country." But I am not so much of a rationalist as to believe that there exist stand-alone arguments for all moral principles. Rather, reasonable political debate involves allusions and reinterpretions of shared traditions; and patriotism provides a rich and diverse store.

3. It seems to me that a democratic government can legitimately decide to instill love of country, whereas it cannot legitimately make people love world Jewry or the Rotary Club. Local democratic governments can also promote love of their own local communities, and that is common enough--but it doesn't negate the right of a national democracy to promote patriotism.

4. Patriotism has a role in a theory of human development that Damon has elsewhere defended. (See W. Damon. "Restoring Civil Identity Among the Young," in Making Good Citizens, ed. D. Ravitch and J. Viteritti. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001). This theory holds that being strongly attached to a community or nation as a child increases the odds that you will care enough about it to scrutinize it critically when you become a young adult. In my own case, as a young boy in the Nixon era, I thought G-Men were heroes and wanted to be one. Now I am a strong civil libertarian. I believe my initial attachment to the US has kept me from simply withdrawing from it, like Robertson Jeffers. However, I'm just one person--and a white, male, middle-class person who has been treated justly by the state. Damon's developmental theory may not work as well for children who face evident injustice.

Thus, as a moral sentiment, patriotism has benefits. However, it can also encourage exclusivity or an illegitimate preference for one's fellow citizens over other human beings. Like all forms of love, it can blind you to faults. These problems are serious, but they can be addressed. After all, some forms of American patriotism identify our particular nation with inclusiveness and the fair treatment of foreign countries.

The teaching of patriotism in public schools raises special problems, several of which Harry Brighouse explores in chapter V of On Education. Here I mention the two most serious concerns:

1. Legitimate government rests on the sincere or authentic consent of the governed. If the state uses its great power over public school students to promote love of itself, that consent is inauthentic. Brighouse (p. 109): "the education system is an agent of the state; if we allow the state to use that system to produce sentiments in the populace which are designed to win consent for it, it thereby taints whatever consent it subsequently enjoys as being non-legitimizing."

This is a serious concern, requiring constant vigilance; but I believe it should be put in context. Schools do not have a monopoly on students' attention. They compete against politicians (many of whom love to denounce the national government), religious leaders (who believe that true sovereignty is God's), and big commercial advertisers (who promote consumption instead of political engagement). Within schools there are plenty of teachers and administrators who hold negative views of the national government. I think the dangers of brainwashing are slight, and it's helpful to present students with an ideal--patriotism in its various forms--that they and their teachers can argue with.

2. A patriotic presentation of history requires whitewashing and distorting the truth about what happened and why. For instance (p. 112) "an educator who has anywhere in her mind the purposes of instilling love of country will have a hard time teaching about the causal process which led up to the Civil War in the US." That's because pursuit of the truth requires one to consider that the Civil War was perhaps faught for economic reasons--a dispiriting thought for a patriot. Likewise, Brighouse thinks that textbooks depict Rosa Parks as a "tired seamstress" instead of a "political agitator" because the former view (while false) better supports patriotism (p. 113).

Obviously, Brighouse has a point--but a close look at his cases shows how complicated the issue is. For example, as an American patriot, I find it deeply moving that Rosa Parks was trained at the Highlander Folk School, whose founder, Miles Horton, was inspired by Jane Addams, whose father, John (double-D) Addams was a young colleague and follower of Abe Lincoln in the Illinois State Legislature. That's only one lineage and heritage in the story of Rosa Parks. It is, however, a deeply American and patriotically "Whiggish" one--and it's truer than the cliché of a tired seamstress. It connects Parks to the profound patriotism of Lincoln (who redefined the American past at Gettysburg) and the pacifist patriotism of Jane Addams.

In any case, why study Parks at all unless one has a special attachment to the United States? If the issue is simply nonviolence, then one should study Aung San Suu Kyi, who is still very much alive and in need of support. I think every young American should know the true story of Rosa Parks, and my reasons are essentially patriotic.

To put the matter more generally: history should be taught truthfully, but it must also be taught selectively. There is no such thing as a neutral or truly random selection of topics. Selecting topics in order to promote patriotism seems fine to me, as long as the love-of-country that we promote is a realistic one with ethical limitations.

Finally, the causal mechanisms here are a little unpredictable. Ham-fisted efforts to make kids patriotic can backfire. But rigorous investigations of history can make kids patriotic. I always think of my own experience helping local students (all children of color) conduct oral-history interviews about segregation in their own school system. They learned that people like them had been deliberately excluded for generations. They took away the lesson that their schools were worth fighting over, that kids could play an active role in history, and that their community was interesting. One girl told a friend from the more affluent neighboring county, "You have the Mall, but we have the history!"

Again, the purpose of our lesson was not simply to teach historical truth and method, but also to increase students' attachment to a community. We were like educators who try to inculcate patriotism, except that we were interested in a county rather than the nation. Our pedagogy involved helping kids to uncover a history of injustice. The result was an increase in local attachment. The moral is that truth and patriotism may have a complex and contingent relationship, but they are not enemies.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:47 AM | Comments (3) | TrackBack

April 10, 2006

the world of DailyKos

In the New York Review of Books, Bill McKibben reviews a new book by the bloggers Jerome Armstrong and Markos Moulitsas Zúniga, Crashing the Gate: Netroots, Grassroots, and the Rise of People-Powered Politics. He uses the opportunity to describe the network of Zúniga's DailyKos, Talking Points Memo, Atrios, and related blogs as "the most ambitious, interesting, and hopeful venture in progressive politics in decades." I found the review a perceptive description of this network (which draws at least half a million people a day); but I have mixed feelings about its impact and potential.

Armstrong and Zúniga describe Howard Dean's appeal in '04 as "ideologically agnostic, purely partisan." That's also a reasonable summary of their style of web-based politics. [See an explicit statement here.] They want to see Democrats play hard. They admire politicians, like Gov. Dean, who attack the Republicans; and they despise Democrats, like Senator Lieberman, who cloud the issue by praising Republicans. Their fury at Lieberman is not ideological, for they will support Democrats who defend the Iraq war--it's rather the anger of a sports fan who thinks that an athlete is not playing to win.

To give Zúniga and his allies their due: They have pioneered techniques that allow many thousands of people to participate in Party politics. People without much money can make small financial contributions that are aggregated strategically on the Web. Participants can also volunteer time and contribute ideas. Devoted fans of the Democrats are becoming players.

Another benefit of this new style of politics is to increase participation and competition in every community, even the "reddest," most gerrymandered of GOP congressional districts. Unlike the official parties (which save their ammunition for "swing" seats), Kos and his allies believe that every election should be contested. That is good because it gives more people opportunities to participate.

I should also note that 2006 is the perfect year for the Kos approach. The main issue really will be incompetence and corruption in one-party Washington, and people (some people) really will vote Democratic simply in order to check and oversee the Republicans. This is one year when it may work simply to attack the incumbent party and promote an alternative set of players.

But that approach didn't succeed in '04, and it won't work in '08. The reason, in my opinion, is a basic imbalance between liberals and conservatives. For a long time, there have been more of the latter than the former.

To be sure, what "conservatives" believe has changed over time. Today, most self-described conservative voters favor Social Security, Medicare, the right to interracial marriage, and free-speech rights for gays--all positions that conservatives opposed forty years ago. Liberals have won many struggles.

But there is not a majority in favor of ambitious change in a liberal direction, whereas there is a majority in favor of the kinds of policies that Republicans favor (which include Social Security and Medicare, along with tax cuts, school prayer, and government surveillance of communications). Real social change requires either new policies or new arguments, not just more aggressive competition.

I am not one of those who claim that Democrats lack "new ideas." The GOP is mostly singing from Barry Goldwater's 1964 hymnal, whereas various Democrats have innovative proposals. The problem is rather that Democrats need consensus about coherent and compelling new ideas much more than Republicans do, and they must make their ideas more central to their campaigns. If neither side has a mandate for change, people will usually vote for the party that best reflects their attitudes on moral issues--currently, the GOP.

I like Kos' wiki space, which allows people to collaborate in designing new policy ideas--that could be revolutionary. However, I don't think that's where the participants are putting their energy; the results, so far, aren't terribly compelling. While McKibben praises the Kos energy policy (and it seems impressive), the health care page, which is more typical, is just a short critique of the status quo with some talking points about several alternatives--nothing novel or particularly persuasive. I can't find any discussion of the new Massachussetts health care plan: a bipartisan effort that deserves consideration and scrutiny. It would be churlish to complain about an ordinary progressive blog that failed to address health care in a substantive way--but DailyKos receives an average of 500,000 daily visits and offers myriad opportunities for those visitors to contribute ideas. If all those people overlook the Massachussets health care plan, then I infer a lack of interest in health policy. In contrast, there is enormous interest in Scooter Libby, Condi's admission that thousands of tactical mistakes were made, Tom DeLay's resignation, etc., etc. Again, a critical style may work in '06; but '08 is not far away.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:28 AM | Comments (3) | TrackBack

April 7, 2006

people who are wrong

I don't usually use this space to pounce on statements I disagree with, but lately I've been saving a list:

1. Robert D. Novak: "There is no sign of extravagant living on [Rep.] DeLay's part -- only bad judgment. DeLay told me last year that he accepted lobbyist-arranged golf abroad because that was his only chance ever to play a game he dearly loved." Of course he took the trip because he enjoyed playing golf. That's hardly an excuse; it's like saying that a politician accepted a yacht from a lobbyist because he dearly loved to sail. If DeLay was short of time rather than money, then he should have played in Bethesda or Texas instead of going all the way to Scotland. The Scottish golf junket was an item of value (especially because DeLay loves the game), and that's what was wrong with accepting it.

2. "'I say let the prisoners pick the fruits,' said Rep. Dana Rohrabacher of California, one of more than a dozen Republicans who took turns condemning a Senate bill that offers an estimated 11 million illegal immigrants an opportunity for citizenship." I have another idea--why not actually pay fair US market wages for farm labor? Then people in leg-irons wouldn't have to pick our strawberries, overseen by guys with shotguns--as Rep. Rohrbacher envisions. Maybe instead of merely naming schools and streets after César E. Chávez, we could actually accomplish what he struggled for.

3. I know this was talk radio, but still: Don Imus executive producer Bernard McGuirk said of the released American reporter Jill Carroll: "Did you hear her comments yesterday? She's wearing the terrorist headgear. And everything points to that." Let's see ... There are are about 1.2 billion Muslims in the world. About half are female. About two-thirds of those are old enough to wear hijab. (That ratio is based on 2006 data for the Middle East, and I realize not all Muslims live there.) Ninety-six percent of the world's Muslims live in Asia and Africa, where they are relatively likely to wear headscarfs or other coverings for religious reasons. Thus I calculate that about 380,000,000 people don the kind of headgear that Jill Carroll wore when released. That's a lot of women for Mr. McGuirk to call "terrorists."

Posted by peterlevine at 11:28 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 6, 2006

federal budget trends

This graph from today's New York Times, although it doesn't break any news, provides essential information for citizens--the kind of substantive context that people need but rarely get.

Some observations:

As the Times notes, 80% of the budget is military spending, entitlements, and interest payments. Few if any conservatives are really calling for cuts in those areas. The debate is about the remaining 20%. There can be big and palpable consequences from cutting small discretionary domestic programs, but the effects on the deficit are very modest. Although there is some truth to the idea that we live in a time of political polarization, with one party that's against government and another that's strongly liberal, it's easy to overstate the difference. Essentially, both parties want to hold federal spending at between 18 and 21 percent of GDP. Even when conservatives have control of both elected branches of government, they let all three major categories of spending increase; and they don't seriously propose any substantial cuts. Nor do Democrats have proposals that would increase domestic spending or cut defense on a scale that would cause fundamental change. The great shifts of recent decades were the doubling of federal mandatory spending as the Great Society programs were fully implemented between 1965 and 1975, and the big decrease in military spending between 1968 and 1978, as we withdrew from Vietnam and ended the draft. As a percentage of GDP, all the other changes (the Carter-Reagan military build-up, the rise in domestic discretionary spending in the 1970s and cuts under Reagan, and the spending increases of the last three years) are relatively small.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:25 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

April 5, 2006

major strategies for educational reform

American public education has been subjected to waves of reform, but much remains constant from generation to generation. Perhaps out of frustration with the slow pace of change, today's advocates and policymakers--whether conservative, centrist, or moderately liberal--now use a fundamentally new strategy. Instead of tinkering with what goes on inside schools, they concentrate on changing the incentive structure. In this post, I describe that strategy and then criticize it on democratic grounds. [Please also click on "comments" to see a response from Harry Boyte that pushes my argument in more ambitious directions.]

The traditional approach assumed that the important questions about education were "what?" and "who?" "What" meant the materials, teaching methods, and curriculum used in actual classrooms. Much of the debate about education from 1900 until ca. 1985 consisted of arguments that the content of instruction should be more rigorous or more relevant, more directive or more experiential, more coherent or more diverse. (See, for example, the Nation at Risk report of 1983). Decisions about content were made--in varying proportions--by state agencies, school districts, principals, and teachers, sometimes with considerable input from citizens, especially those who served on school boards and PTAs. Thus the education debate was mostly about what should be taught, and arguments were directed to state and local school leaders.

People also debated "Who?", meaning the identity of the teacher--how she was qualified and selected--and the composition of classes. The influential Coleman report of 1966 led people to think that the teacher was relatively unimportant but that the mix of students was crucial. Poor kids needed to be exposed to middle-class students; kids with disabilities needed to be mainstreamed. Thus, for a generation, the main issues in federal education policy were desegregation and integration. There was also much debate about the pros and cons of "tracking" students--separating them by interest or ability level. Again, this was a debate about "who?"

Despite all this attention to "what?" and "who?", education didn't change fast enough for many reformers, or not in the directions they wanted. Recently, they have given much more attention to "why?"--in other words, to the incentives that are supposed to motivate administrators, teachers, and students to behave in certain ways. There are three major types of proposal for changing the incentive structure in education, thus causing students and educators to answer the "why?" question differently:

1. Impose regular, standardized tests with carrots and sticks. (Then the answer to "Why study?" is "To pass the test." "Why teach effectively?" -- "To get the kids through.")

2. Increase the degree of parental choice and allow funding to follow students. ("Why teach effectively?" -- "To attract pupils.")

3. Increase funding for schools, or equalize funding among districts. ("Why work in a difficult school setting?" -- "To earn a reasonable salary.")

None of these approaches is completely new. Liberals have been advocating higher teacher salaries for a long time. School choice was first defended (to my knowledge) by Milton Friedman in 1955. There were high-stakes tests before No Child Left Behind.

Nevertheless, the tenor of the debate has shifted. Politicians and policymakers now show an extraordinary lack of interest in the "what" and "who" questions. They seem to agree with the economist Gary Becker about the futility of looking inside schools: "What survives in a competitive environment is not perfect evidence, but it is much better evidence on what is effective than attempts to evaluate the internal structure of organizations. This is true whether the competition applies to steel, education, or even the market for ideas." Becker is a libertarian, but liberals who want to pay teachers more to teach in inner-city schools are also interested in competition--they just want schools to compete better in the job market.

It's important to think about incentives; that's one of the main themes of modern social science. Asking schools to educate better (or differently) without changing their incentives won't work. On the other hand, there are democratic reasons not to ignore the internal policies and choices of schools:

1. If the market or the authorities that create standardized tests control schools by manipulating the incentives, there is little scope for parents and other community-members to deliberate about local education. (It is especially difficult to deliberate about norm-referenced exams.)

2. If parents create incentives for schools by choosing where to send their kids, I worry that they will seek private goods for their own children (such as marketable skills and membership in exclusive peer groups) rather than public goods (such as civic skills, experience with democracy, and exposure to diversity). I also worry that parents who are not well-educated themselves will choose schools without the demanding extracurricular activities and enrichment programs that generate civic skills. (However, I must admit that school systems without choice also provide lousy extracurriculars for low-income kids.)

3. If educational authorities create incentives for schools by imposing standardized tests, all the pressure will be in favor of outcomes that can be measured on exams--especially individuals' factual knowledge and cognitive skills. It is much more difficult, or perhaps impossible, to create high-stakes assessments of moral values, habits and dispositions, and collaborations. Yet a democracy needs people who collaborate and who have civic virtues and habits.

4. All these approaches to reform (including the liberal tactic of increasing funds for teachers' salaries) involve extrinsic motivations. But people can also be intrinsically motivated to teach and to learn. Democracy needs citizens who understand the intrinsic value of working and learning together. Besides, as I argued previously, it is offensive and alienating to treat good teachers and students as if they lacked internal goals and will only respond to carrots and sticks.

I think there are good arguments for increasing teacher salaries, imposing at least some tests that have high stakes, and providing some degree of school choice. However, if the above arguments are persuasive, we also need vigorous public debates about what goes on inside schools.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:27 AM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

April 4, 2006

thickening to empire

Robinson Jeffers, "Shine, Perishing Republic" (1924)

While this America settles in the mould of its vulgarity, heavily thickening to empire

And protest, only a bubble in the molten mass, pops and sighs out, and the mass hardens,

I sadly smiling remember that the flower fades to make fruit, the fruit rots to make earth.

Out of the mother; and through the spring exultances, ripeness and decadence; and home to the mother.

You making haste haste on decay: not blameworthy; life is good, be it stubbornly long or suddenly

A mortal splendor: meteors are not needed less than mountains: shine, perishing republic.

But for my children, I would have them keep their distance from the thickening center; corruption

Never has been compulsory, when the cities lie at the monster's feet there are left the mountains.

And boys, be in nothing so moderate as in love of man, a clever servant, insufferable master.

There is the trap that catches noblest spirits, that caught--they say--God, when he walked on earth.

Notes:

"Empire": not, in 1924, mainly a result of conquest and invasion, but a metaphor for all-consuming production and consumption; the American empire of things.

"You making haste haste on decay": by rushing, you (Americans) speed up the process of decay.

Be "in nothing so moderate as in love of man": contrast the Biblical view: for example, 1 Peter 4:8 "And above all things have fervent charity among yourselves: for charity shall cover the multitude of sins."

"There is the trap": i.e., love of people, which might tempt the poet's sons to participate in national affairs instead of withdrawing to solitude. (But why does the poet, safe in his mountains, take the trouble to address the republic and its corrupt cities?)

Posted by peterlevine at 7:31 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 3, 2006

political equity

Although some degree of economic inequality is inevitable or even desirable, all citizens should be equals before the law and government. However, in practice, people with more money and education tend to be more politically effective and to dominate civil society. In the United States, there are striking correlations between most forms of civic engagement and individuals' education and wealth. The following graph shows self-reported levels of participation for those who say they belong to the working class and who have a high school diploma or less, versus those who call themselves middle class and hold a college degree or more. The more privileged group is at least twice, and often five times, as likely to participate in all categories:

In principle, there could be an equitable political system with low levels of participation, so long as every demographic group and social stratum participated at the same rate. Then the participants would be a representative sample of the whole population. There are even democracies in which the poor and weak outvote the powerful: for example, in India, where the "untouchable" or Dalit class has higher turnout than the high-caste Brahmins. That is because the poor outnumber the wealthy in India, and political parties have persuaded them that they can benefit tangibly from capturing the state by voting. It seems relatively difficult to mobilize the least advantaged in a country like the United States, where the median family is reasonably well-off and well-educated, and the poor form an electoral minority, incapable of winning elections even if their turnout is high. Also, a sophisticated, media-rich society with a strong independent voluntary sector and a high degree of political freedom rewards people who have resources-—money, skills, energy, or time--to contribute.

Thus the best method for increasing political equity in a country like the United States is to raise the total number of people who participate in politics and civil society. When total numbers rise, the poor and poorly educated are better represented. This is not a utopian idea. Voter turnout among male citizens reached 81.8 percent in the 1872-—much higher than it is today. There is no essential reason why basic forms of participation such as voting couldn't return to those levels.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:37 AM | Comments (2) | TrackBack