« May 2005 | Main | July 2005 »

June 30, 2005

why moral positions should be explicit in literary criticism

During a conversation with a friend on Wednesday, I realized why most contemporary literary criticism bothers me--from a moral perspective. (I use the word "moral" broadly, to mean any issue about how we should live or how our institutions should function.) Although there are some exceptions, whom I admire, most critics have moral agendas that they keep implicit.

They look in fiction for themes of race and gender, politics, or markets because they have views about those topics themselves. For instance, to identify an authorial voice with "imperialism" is to criticize the author; to say that he "subverted" a "patriarchal order" is to praise him. Yet literary critics rarely make their own moral positions explicit. Wayne Booth and Martha Nussbaum have explained critics' resistance to explicit moralizing as a result of several assumptions. Critics tend to believe that moral opinions are arbitrary, that openly moral evaluation of fiction might justify censorship, that moral criticism must be reductive, and so on. Yet implicit moral evaluation remains very widespread.

I don't believe that literary critics should supply elaborate philosophical arguments in favor of their moral views. I'm a "particularist," someone who believes that moral judgments are about concrete cases, not about general categories. Therefore, I'm not a big fan of abstract philosophical arguments, even when they appear in philosophy books written by professionals. It would be even stranger--and less valuable--if abstract moral argumentation started to appear in works of literary criticism. For example, imagine that a critic had to prove that imperialism is bad, before he or she could use the word "imperialism" with a negative connotation in an interpretation of Shakespeare's Tempest or A Passage to India. This would not be helpful.

Nevertheless, I do believe that critics should explicitly state the moral views that are implied by their literary interpretations. Making explicit one's own moral position forces one to confront the possibility of exceptions, tradeoffs, and limits. For example, "imperialism" has a bad ring to it. But what are we against, if we oppose the imperialism that can be found, for instance, in The Tempest? (Whether Shakespeare approves of that imperialism is a different question.) If forced to express a moral view explicitly, instead of merely using "imperialism" as an epithet, a critic would have to adopt a position like one of these:

Fundamentally, I believe it's irresponsible not to state one's own moral positions clearly enough that their scope and implications are evident. I suspect that many literary critics are willing to be "irresponsible" because they see themselves as outsiders, as adversaries of mainstream culture and the social order. It's not their job to plan or manage societies; they just identify bad things like imperialism and violence. But this stance strikes me as bad faith, since professors in rich countries are actually quite powerful. Irresponsibility is also a recipe for the alienation that I described here recently.

Posted by peterlevine at 2:18 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 29, 2005

costs and benefits of voting

When you ask citizens why they didn't vote, many say that the process was inconvenient and time-consuming. (See the table below, which uses 2002 Census survey data.) Their answers suggest that we could increase participation by making it easier to vote, e.g., by turning election day into a national holiday, by allowing early voting or voting-by-mail, or permitting citizens to vote online. But evidence from states that have adopted some of these reforms shows a modest impact. The Motor-Voter law, which was supposed to increase turnout by simplifying registration, did raise the registration rate but not actual turnout in elections.

I have come to think that answers to surveys like the following are misleading. After all, costs and benefits are two sides of the same coin. Someone who says that he lacked the time to vote is also saying that voting was not especially important to him. He actually had time; but other things seemed relatively more pressing. I think the turnout issue comes down to motivation. When issues seem important, when outcomes are uncertain, and when campaigns reach out to mobilize and inform voters, turnout goes up--as it did sharply in '04.

| too busy, schedule conflicts | 27.1% |

| out of town, away from home | 10.4 |

| transportation problems | 1.7 |

| all time and convenience problems | 40.6 |

| not interested or felt vote would make no difference | 12.0 |

| did not like candidates or campaign issues | 7.3 |

| all dissatisfaction issues | 19.3 |

| illness or disability | 13.1 |

| bad weather | 0.7 |

| all special barriers | 13.8 |

| registration problems | 4.1 |

| forgot to vote | 5.7 |

| other reasons (not specified), don't know, or refused | 16.5 |

Posted by peterlevine at 7:07 AM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

June 28, 2005

the future of public broadcasting

I know quite a few people who work in and around public broadcasting; and over the years I have been involved in several behind-the-scenes projects with them. So my heart is with public radio and television. However, I wonder if there really is a future for federally-funded mass media. It seems to me that several major factors are working against it:

1. Liberals and conservatives both sincerely believe that the mainstream private media are strongly biased against them. This doesn't mean that they are both right; but their feelings are genuine and deeply held. It's difficult to influence Fox or CBS if you don't like its prograns, but any organized group can apply political pressure to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. Therefore, as long as liberals and conservatives feel victimized by most of the mass media, they will be sorely tempted to try to move CPB in a favorable direction. Trying to argue for "neutrality" or "balance" won't protect public broadcasting, because there is no such thing as an ideologically neutral form of communication. Nor will it work to argue for "independence." Some governing board must run CPB, and its members must somehow be chosen by politicians. Short of empanelling a jury of random citizens to manage public broadcasting, there is no such thing as "independence."

2. Many Americans are moved by what I have called the "Jeffersonian principle." Jefferson once wrote, "to compel a man to furnish contributions of money for the propagation of opinions which he disbelieves and abhors, is sinful and tyrannical." It's actually impossible to have a government without compelling people to fund the "propagation of opinions" that they dislike. For example, as long as we pay the salary of a president, he (or she) may say things we abhor. Nevertheless, Americans see a moral harm if they are forced to pay tax dollars for communications that they disagree with. It doesn't matter how trivial the cost. Therefore, people will get much more angry about programming supported by CPB than anything on the commercial networks.

3. CPB has always had a top-down model: famous and distinguished people conduct a "peer review" processes to allocate funds. This is elitism, for better and for worse. It certainly doesn't help to build a strong popular base.

4. A major rationale for public funding was the monopoly of the major networks ca. 1970. On its face, the media environment appears much more competitive and pluralistic today.

5. Much of the most creative "public media" doesn't seem to need federal money or access to the broadcast spectrum. It consists of websites, low-power radio stations, blogs, podcasts, and other quasi-amateur work.

I'm torn between two strategic arguments. One says: All the grassroots, amateur media work is small potatoes. It's destined for a niche market of hippies and hackers. We can work to grant low-power radio stations more rights and to relax certain intellectual-property laws to enhance the free sharing of information, but these reforms will have a marginal impact, at best. Ultimately, any great democracy must create an organized, mass public media space, of which the BBC is a classic example.

The other says: Congress will never appropriate substantial amounts of money for a broadcast system that's of high quality and independent (whatever that would mean). Fortunately, many-to-many media like blogs can compete with mass commercial media, because the former are more creative and more fun. Thus the realistic strategy is not to worry about CPB but to put our energies into a media system that's pluralistic, decentralized, and basically free of federal dollars.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:56 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 27, 2005

the civic renewal movement (3)

In two recent posts, I began to describe the current movement for civic renewal. First, I listed some key elements of the movement; then I identified some common themes. In this last of the three posts, my topic is "the strength and growth of the movement."

I am convinced that the civic renewal movement now forms a reasonably tight and robust network. My basis for that claim is the set of social ties that I observe as part of my official work, which involves numerous meetings and conferences in many parts of the United States (probably more than 75 per year). I am constantly struck by the appearance of the same people, or of people who know others in the broader network.

This is a mere impression. It could be tested with rigorous network analysis, which I believe would be quite useful. In brief, researchers would begin with several key organizations (such as the ones listed above) and ask decision-makers what other groups they collaborate with. Researchers would then move to those groups and ask, in turn, about their collaborations. Software can automatically generate network maps based on such data. I would hypothesize that a network map of civic renewal would show many links binding the whole field.

Lacking the resources actually to conduct such a study, I have used a very imperfect substitute. Instead of asking people to list their partners, I have examined electronic links among organizations’ websites. Those links that are captured by the Google search engine can be depicted as a diagram. (Very regular readers may remember me doing something like this once before.) The image below shows major web links from three nodes--the National Allicance for Civic Education, the Deliberative Democracy Consortium, and the Pew Partnership for Civic Change--and from groups to which they link. I chose these three nodes as starting points because of my (highly subjective) sense that they represent important consolidations of practice since the 1990s. In particular, civic education and deliberation were fractious fields that began relatively late to form bridging networks—and then only as a result of rather careful and deliberate diplomacy.

Points on the graph represent organizational websites. Lines represent links among sites, as detected by an automated (and imperfect) Google search. I have written out the names of some of the points for illustrative purposes. The phrases in red are my generalizations about types of organization that cluster together.

Overall, the diagram shows a robust network: one can move by multiple paths from each sector of civic renewal to the others. I am certain that a more detailed process would reveal additional links. For example, I know that people in the civic technology sector (bottom left) work with people in service-learning (top left), even though the diagram shows no direct links.

It is important to note that the civic renewal movement may be robust and coherent, but it is insufficiently diverse. Most of the organizations listed above are predominantly, sometimes exclusively, white. Minorities are best represented in the work that involves community economic development; they are not well represented in civic education or in much of the deliberation field.

My second claim involves growth. I believe that the civic renewal movement is stronger, larger, and more influential than it was 10 or 20 years ago. This is a difficult claim to substantiate. When we work in social movements, we tend to make two historical assertions without hard evidence. To motivate ourselves and to win allies, we tend to assert that our problem is getting worse, and that a movement has recently formed to counteract it. Given the “churning” that is endemic to American civil society, it is not obvious that the country’s civic condition really has declined or that a civic renewal movement has recently developed. Maybe every generation could make the same claims.

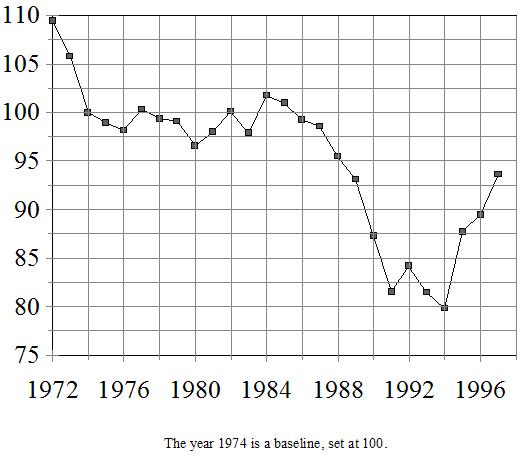

However, some aspects of civic life certainly have declined, and some new strategies and organizations certainly have formed to renew civil society. When the National Commission on Civic Renewal created an Index of National Civic Health (INCH) in 1999 (comprising 22 variables), we generated the trend line shown below.

I believe that the steep decline of INCH between 1984 and 1991—reflected in almost all of its 22 component variables—created genuine alarm and caused people to focus on civic renewal by the mid-1990s. For various reasons, including the work of these people, the situation had begun to improve by 2000. This is not to say that INCH includes all relevant variables or that there is consensus in favor of the proposition that “civic health” had declined. But there was pretty widespread agreement, rooted in people’s daily experience, that we had a problem. (Unfortunately, I don’t have comparable data for after 2000, so I can’t continue the trend line after Sept. 11 and the first Bush Administration.)

If I were to tell story of the current civic renewal movement in America, it would incorporate the following developments and episodes:

Posted by peterlevine at 1:30 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 24, 2005

the high school dropout problem

I'm at National Airport, on my way to Georgia to speak about the Civic Mission of Schools. I was just on Capitol Hill for an American Youth Policy Forum on high school dropouts. Paul E. Barton of the Educational Testing Service (ETS) gave a very useful presentation. Some highlights:

Growing numbers of 16-year-olds are taking the GED instead of finishing high school. It's unclear why: they may be "pushed out" (encouraged to leave school so that they won't count in dropout statistics or cause disciplinary problems), or they may be "drawn out" by the prospect of a high-school equivalency degree without all those boring and demeaning courses and dangerous school hallways. Obviously, it would be best to make high schools more rewarding for more kids. However, I wonder whether it would help to create a tougher, more highly valued exam as alternative to the GED; this could truly substitute for a high school diploma. Then kids who were ready for work or college at 16 or 17 could finish early and have decent prospects.

Posted by peterlevine at 3:34 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 23, 2005

The Deliberative Democracy Handbook

It's out! I have my copy of the Deliberative Democracy Handbook, co-edited by John Gastil and myself. There are 19 chapters (mostly co-written, so there are about 30 authors in all). For the most part, each chapter is devoted to a different, practical process for engaging the public in deliberations and influencing policy. The processes come from all over the world. The book has its own website with more information.

It's out! I have my copy of the Deliberative Democracy Handbook, co-edited by John Gastil and myself. There are 19 chapters (mostly co-written, so there are about 30 authors in all). For the most part, each chapter is devoted to a different, practical process for engaging the public in deliberations and influencing policy. The processes come from all over the world. The book has its own website with more information.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:45 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 22, 2005

a totally new fundraising strategy for civic engagement

Deliberative Polling is an important innovation in "civic engagement." Citizens are randomly selected to meet as a kind of large jury for several days. They hear testimony from experts, deliberate at length, and finally vote their opinion on a contentious issue. Deliberative Polling has been used by television broadcasters in the US, Britain, and Australia. The participants deliberate, interview national political candidates, and report their results on TV. Deliberative Polling has also been used as part of the formal process for regulating public utilities in Texas, among other cases.

Deliberative Polling is relatively expensive, and everyone in the civic renewal field constantly struggles with money issues. But get this--the Texas prosecutor who is investigating Rep. Tom DeLay, Ronnie Earle, has forced Sears, Cracker Barrel, Questerra, and Diversified Collections Systems to contribute large amounts of cash to the Center for Deliberative Polling at UT-Austin. These companies were accused of making illegal contributions in connection to the DeLay case, as part of what Earle called "an effort to ... control representative democracy in Texas." But they settled out of court by agreeing to support deliberative democracy in the state.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:20 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 21, 2005

the civic renewal movement (2)

Yesterday, I listed some major fields of practice that I consider important to the overall movement for civic renewal in America. Today (while I attend a day-long meeting on service-learning), I will summarize some of the common themes that define all those fields.

1. Civic renewal work is open-ended: Instead of defining problems and solutions in advance, many leaders of the networks that I described yesterday prefer to create open forums in which diverse groups of citizens can set their own course. I realize that perfect neutrality is impossible. (Even in a deliberative exercise, someone must issue an invitation that will somehow shape the conversation that ensues.) Besides, being "open" to diverse views is not always wise; it's fine to commit oneself to fighting poverty or AIDS, or even defeating a particular political party. But the civic renewal movement is defined by a commitment to helping citizens make their own decisions. I find this commitment appealing for several reasons: it reflects the best spirit of liberal education, it builds citizens' capacities for self-government, and it creates the hope that we may together develop alternative policy options and ideologies, for none of the existing ones seem impressive.

2. Civic renewal work combines deliberation with action: Many of the projects I described yesterday involve careful, reflective conversations among diverse people. They also involve political work--not only voting or otherwise influencing the state, but also managing common resources and building local institutions. Deliberation without work is empty, but work without deliberation is blind.

3. Civic renewal work treats the political culture as an important variable: There are ideologies according to which the "root causes" of poverty, crime, racial exclusion, and even environmental degradation are all economic. If that were true, it would be superficial to work on public deliberation or civic education; we should first make society more equal and fair. Under conditions of injustice, public discussions would simply reflect (and perhaps even legitimize) the inequality of knowledge, status, power, and other resources. However, participants in the civic-renewal movement reject this argument, seeing it as a recipe for hopelessness--and a way to avoid actual public deliberations). Instead, they place their bets on enhancing people's political opportunities, even while economic conditions are unfair.

4. Civic renewal work builds sustained civic capacity: Although each project is devoted to a specific task, the leaders of these projects are always thinking about other matters as well--especially, how to involve more people in politics, strengthen the social ties that individuals can use to solve common problems, enhance institutions, and make better information available.

5. Civic renewal work is non-partisan: There is nothing wrong with affiliating with a party or holding ideological views (I do). However, open-ended work is, by definition, distinct from partisan work. At a time of intense partisan polarization, it's important that some people, some of the time, are concerned about the overall political system and culture in which our two major parties compete.

6. Civic renewal work is concerned with the human scale: Politics certainly takes place at a macro level--in national elections, the mass media, and struggles among nations. The macro level is important, but so is the micro, because it is only in groupings of modest, tangible size that people can develop the skills, attitudes, and networks that allow them to participate effectively in national affairs. (See "two levels of politics" for more on this.)

Posted by peterlevine at 7:30 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 20, 2005

the civic renewal movement

In three consecutive posts this week, I plan to argue that there is a strong, coherent, interconnected movement for civic renewal in America. This first post simply describes some major elements of that movement. In no particular order, they include:

deliberative democracy work

For some thirty years, people have been organizing groups of citizens at a human scale (say, five to 500 people) to discuss public issues, with background materials and some kind of moderation or facilitation. Major organizations in this field include the National Issues Forums (self-selected adults deliberating face-to-face, with published guides), Study Circles (a similar process, but usually more embedded in community organizing), Deliberative Polls (randomly selected citizens who meet for several days), and online forums such as E-The People. Models and practices are proliferating; in fact, my forthcoming book, co-edited with John Gastil, describes more than a dozen in detail. Most of the relevant groups have come together in the Deliberative Democracy Consortium.

Work on deliberation shades into conflict-mediation efforts, inter-group dialogues (which usually involve discussions of identities and relationships rather than issues), and even new mechanisms that governmental bodies are using to "consult" the public. The National Coalition for Dialogue and Deliberation is a broad forum for all these practices.

community-based wealth generation

Deliberation also occurs within non-profit corporations that aim to create jobs and income, and that are formally tied to neighborhoods or to specific rural areas. These corporations include co-ops, land trusts, and community development corporations (CDCs), among others. Community Wealth.org is a good clearinghouse of information. As I argued last week, capital-mobility is a major challenge for democracies, because citizens must do what companies want or else investments will move away. Creating corporations that are tied to communities is a promising solution, and there are more of these corporations every year.

democratic community-organizing work

The Industrial Areas Foundation (which has created and worked with many CDCs and other neighborhood corporations) represents a form of community organizing that builds poor people's political capacity as well as their wealth. Instead of defining a community's problems and advocating solutions, IAF organizers encourage relatively open-ended discussions that lead to concrete actions (such as the construction of 2,900 townhouses in Brooklyn, NY), thereby generating civic power. IAF is a major force in this field, but not the only one. A related stream of practice is Asset-Based Community Development (ABCD), which emphasizes the importance of cataloguing and publicizing the assets of any community as a prelude to development. The aim is to shift from thinking of poor communities as baskets of problems, and instead recognizing their intrinsic capacities.

civic education

From the 1960s through the 1990s, most scholars argued that explicit civic education had no lasting effects. In the same period (although not only because of the scholarly naysayers), schools tended to abandon civic courses and curricula. Nevertheless, a set of nonprofit organizations continued to provide textbooks, programs, and seminars for teachers. These groups included the Center for Civic Education, the Constitutional Rights Foundation, Streetlaw, and the Bill of Rights Institute, among others. Their programs have usually combined focus on perennial democratic principles with the investigation of immediate issues relevant to students. They also tend to combine experiential learning (e.g., debate, community-service, advocacy) with reading and writing.

Since 1999, these nonprofits, traditionally fractious, have come together to create the National Alliance for Civic Education and then the Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools. The Campaign is a coalition of the leading organizations that specialize in formal civic education, plus major organizations that have pledged to support their agenda, including the American Bar Association, both national teachers' unions, the National Conference of State Legislatures, and 35 more.

service-learning

A particular strand of civic education involves combinations of community service with academic study of the same topic. Service-learning is popular not only in k-12 schools (about a third of which now offer it), but also in colleges. Much service-learning is non-political; it involves acts of charity and service, such as cleaning up a park or visiting elders. Often the underlying theory derives from experiential education (i.e., kids learn best from doing) and doesn't have much to do with civic or political values. However, within the large field of service-learning, there is avid discussion of how to engage young people in solving social problems--as a pedagogy.

community youth development

Much of the best civic education takes place not in schools but in youth groups that are concerned primarily with healthy adolescent development. Increasingly, adults in 4-H, the Scouts, and urban youth centers believe that engaging teenagers in studying and addressing local social problems is a good way to develop their intellects and characters and to keep them safe. Much like proponents of asset-based community development, these people want to treat their subjects (in this case, kids) as partners and assets, not as bundles of problems. They also emphasize local geographical communities as excellent subjects for youth to study and as venues for youth work. The Innovation Center for Community and Youth Development and the Forum for Youth Investment are important hubs in this movement. The Coalition for Community Schools brings a similar set of values to its work with k-12 schools.

work to defend and expand the commons

The "Tragedy of the Commons" is the tendency of any resource that isn't privately owned to be degraded as people over-use it or fail to invest in it. The Tragedy is real: consider the collapse of global fish stocks due to over-exploitation. However, many un-owned resources actually flourish for generations or even centuries. And robust new "commons" are developing: above all, cyberspace (understood as a whole structure, not as a series of privately owned components). Scholars like Elinor Ostrom, working closely with communities, have begun to understand the principles that underlie effective commons--whether they happen to involve grasslands or scientific knowledge. Practical work to protect and enhance commons is underway within the American Libraries Association and in the environmental field. Since the keys to robust, sustainable commons include public deliberation and the wide dispersal of civic skills and attitudes, commons work is closely related to civic renewal.

work on a new generation of public media

When we hear the phrase "public media," we may think first of publicly subsidized organizations that produce and broadcast shows to mass audiences. Indeed, within the constellation of PBS, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, NewsHour Productions, and the state PBS affiliates, there is some interesting work going on that could support civic renewal. The Center for Social Media recently received a large Ford grant to explore the future of public media. People at that Center recognize that "public media" is much broader than CPB; it should include any use of any communications medium to promote the creation and sharing of ideas and cultural products relevant to public issues. So defined, the most compelling public media today originates from thousands of grassroots groups that are creating websites, email-based discussions, and audio and video segments. J-Lab, the Institute for Interactive Journalism, represents a hub for this work.

There is also relevant work inside newspapers. In the 1990s, many professional journalists were interested in writing the news in ways that would better support public deliberation. That movement--variously called "civic journalism" or "public journalism"--has run out of steam as a political force, but it has left an important residue in newsrooms. Furthermore, because of the Internet, newspapers are desperate to become more "interactive." Although interactivity can be a mere gimmick or a way to enhance an individual's experience on a website, some journalists are experimenting with interactive features like blogs for democratic purposes. Jay Rosen keeps track of them.

Public media work and work to defend the commons come together in the field of positive hip-hop. Youth of all races are now producing music and poetry that confronts serious social problems and that depicts themselves as three-dimensional human beings, not as thugs. Hip-hop usually involves borrowing, quoting, and parodying snippets from the mass media. This is a powerful democratic activity, but it can violate over-restrictive copyright laws--which is why the idea of a commons is relevant. Young people in the hip-hop world are increasingly aware that they have a stake in dry issues like copyright.

development of social software

I mentioned blogs in the last section. They are one example of a new behavior that is enabled by software. Many developers are working on other software to enhance discussion and collaboration. Examples include "real simple syndication" (RSS), wikis, and "content management" systems that allow many citizens to create public documents together. (A great example is a whole newspaper, the Bakersfield, CA, Northwest Voice, that consists entirely of material submitted by citizens.) While some of this frenzied innovation is driven by purely technical interests and goals (and by the prospect of making money), there is also a strong subculture of "hackers" who are committed to the commons and to democracy.

the engaged university

Some universities are playing central roles in civic renewal work, as they move from service to partnerships; as they rediscover the importance of the geographical communities in which they are located; as they reflect on the democratic potential of their power as employers, builders, and consumers; and as they conduct sophisticated research that requires learning with and from non-academics. Minnesota (see the Council on Public Engagement), Michigan (see Imagining America), Penn (see the Center for Community Partnerships), and Maryland (see the Democracy Collaborative) are leaders. Campus Compact is a major hub.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:12 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 17, 2005

focus

At the beginning of the Deliberative Democracy conference today, our excellent moderator said that the one factor that affects the quality of a meeting that is in our control is the degree to which we maintain focus. It's crucial really to be in the room, not distracted by thoughts of going online or checking voicemail or planning one's next day. I did a good job of focusing, as I will again on Friday for Day Two of the conference. However, her caution was really necessary. I'm finding it almost impossible to be fully "present," anywhere. My days this summer are almost completely booked and scheduled, and waiting for me late at night is always a very long list of emails to answer. I don't mind any of this work; in fact, I seek most of it voluntarily. It's a series of interesting opportunities. It's also coherent at a conceptual level--all of it connects to "civic renewal" in one way or another. But at a psychological level, I feel increasingly fragmented; unable to concentrate on any task because of the pressure to keep thinking about the other ones. Everyone I know has the same complaint, which suggests that the problem has sociological (or technological) roots; it's not simply my fault for over-committing myself.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:06 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 16, 2005

a researcher-practitioner meeting

Yesterday, I spent an interesting day talking to some people who work in the world of public broadcasting about a project to produce high-quality news shows for use in high schools. A lot of the discussion was about how young people might contribute to the shows as well as use them.

Today is the second annual Researcher & Practitioner Conference of the Deliberative Democracy Consortium. That's a mouthful. It's also an interesting and unusual project. Last year, we convened a bunch of people who organize citizens' deliberations at a human scale--in towns and cities. We also invited some scholars who study the process of deliberation. The whole group spent two days developing a shared research agenda and planning some valuable research projects that could be conducted by teams of scholars and practitioners. Thanks to the Hewlett Foundation, we had more than $100,000 to allocate (through a competitive process) to teams that formed at the conference.

This is the second year, so we will be hearing reports from the teams that received funding. We will also revise our research agenda and allocate another batch of funds from Hewlett. As a by-product of these conferences, I believe we are strengthening a network that consists of academics and practical folks--something that's not nearly as common as it should be.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:01 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 15, 2005

wealth-building strategies for communities

Yesterday, my colleagues at the University of Maryland's Democracy Collaborative unveiled a new website called Community Wealth.org. It contains a mass of practical information about alternatives to the standard business corporation, including "community development corporations (CDCs), community development financial institutions (CDFIs), employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs), community land trusts (CLTs), cooperatives, and social enterprise." Gar Alperovitz, Jessica Gordon Nembhard, and other Maryland colleagues have shown that these wealth-generating organizations are rapidly growing and are often highly efficient and sustainable. Alperovitz also has a new book on the subject, which has been excerpted in Philosophy & Public Policy Quarterly (a journal produced by my shop).

These are my two favorite arguments for expanding alternatives to standard corporations:

1) The traditional approach to equity--taxing and spending after the fact--has encountered strong popular opposition in all Western democracies. Besides, it makes the recipients of government aid dependent on the state. Wealth-generation is a preferable strategy for both political and substantive reasons.

2) Alternative economic institutions like CDCs and co-ops are more rooted in communities, less able to move their investments. One of the biggest weaknesses of democracy today is the mobility of capital. As Alperovitz notes in the excerpt, a corporation can influence political decisions in multiple ways, including the "implicit or explicit threat of withdrawing its plants, equipment, and jobs from specific locations." Besides, "in the absence of an alternative, the economy as a whole depends on the viability and success of its most important economic actor--a reality that commonly forces citizen and politican alike to respond to corporate demands."

If there is no alternative to the standard corporation, then democracies really must do what firms want. Trying to restrict capital flows simply violates the laws of the market and will impose steep costs. In the market we have, it is not corrupt when democracies favor corporations; it's just realistic. However, Alperovitz and his colleagues are showing that there is an alternative to the corporation. It's possible to increase the wealth of people in poor communities by creating economically efficient organizations that are tied to places.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:26 AM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

June 14, 2005

profound in their superficiality

While I was waiting for take-out food yesterday, I heard a talking head on what appeared to be a news show announce that the Michael Jackson trial was "without question the trial of the decade so far, and therefore of the century." I can actually think of some other contenders for that title. For example:

Any other suggestions for the top ten?

Posted by peterlevine at 12:01 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

June 13, 2005

on spending for schools and the idea of "root causes"

I mentioned last week that Rethinking Schools is a fine publication. The current issue on small schools is full of information and insights. For example, Wayne Au makes the point that small institutions are at a disadvantage under No Child Left Behind, because they have so few students that they will see big random swings in their annual test scores--and failure to improve their mean scores every year leads to sanctions. In general, the magazine is useful as a distillation of progressive thinking about education. I endorse most of its content, but I want to register some dissents, because I think the way forward for the left is to criticize our traditional ideas and develop new ones.

Reflecting traditional left-of-center ideology, several contributors to Rethinking Schools stress that creating smaller high schools--even if it's a good idea--can't solve the "root causes" of society's problems, which include poverty and racism. Now, I agree completely with Craig Gordon that it is unjust for a single corporate CEO in his city to be paid as much as 600 new teachers. But I'm not at all sure that it's wise to treat economic inequality as the "root" issue, while viewing such matters as the size and structure of schools as superficial.

There is presumably a vicious cycle in which poverty and racism contribute to poor educational outcomes (and also to crime and morbidity); low-income communities receive substandard government services; and problems like under-education, disease, and crime generate and preserve poverty. If this vicious cycle exists, then we ought to intervene wherever we think we'll have the most impact. For example, it appears that cities can reduce crime by changing their policing strategies, even when the poverty rate remains constant. In turn, lower crime rates should encourage economic investment and growth in urban neighborhoods. So the liberal nostrum that poverty is the "root cause of crime" was at least partly a tactical mistake.

The traditional mechanism for increasing equality is after-the-fact. Once people have obtained their incomes in the marketplace, we tax them progressively and spend the proceeds on social programs. I think our tax system should be more progressive, because everyone agrees we have growing needs (including the federal entitlement programs and interest payments on the national debt); we are not meeting those needs; and the only fair way to increase federal income is to raise taxes on wealthy people. But there is no clear political strategy for increasing equity through redistribution. Nor will poorer Americans automatically benefit from more spending in sectors like education.

The U.S. Department of Education recently reported that per-pupil spending on public school students increased by 24 percent, adjusting for inflation, between 1990 and 2002. That is a big increase that enables us to test the proposition that more education spending would be better for the least advantaged America. I see four possibilities ...

1) The new money has purchased substantial improvements in educational outcomes for all Americans. That would counter the angry and sad rhetoric of Rethinking Schools. However, it would support the case for even more spending.

2) The money has not obtained improvements because it has not been well spent; that would underline the importance of institutional reform.

3) The money has been spent on kids who were better off to start with; hence the outcomes of poor kids did not improve. I find this story unlikely, given the recent pressure for equity. But it is possible.

4) The Department of Education is wrong to claim a 24% real increase. That would be a scandal, and it seems implausible.

I don't know which of these four hypotheses is correct, but much depends on the answer. I intend to keep an open mind about education spending until I know more. Meanwhile, I have the feeling that Senator Obama was right when he said at a commencement address last week: "We'll have to reform institutions, like our public schools, that were designed for an earlier time. Republicans will have to recognize our collective responsibilities, even as Democrats recognize that we have to do more than just defend old programs."

Posted by peterlevine at 11:32 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 10, 2005

policy analysis, for undergrads

I have an opportunity to teach a special undergraduate seminar next spring. I'm not sure if I'll accept, because it would mean doing less of something else. However, it's fun to think about. I'm imagining that students would spend the whole semester producing background materials about k-12 education in Prince George's County, MD. The materials would be published on a new part of the Prince George's Commons website to accompany an online public deliberation about local education. The students would collect such useful and relevant background as:

I think I would require everyone to read some philosophical arguments about education, because students can't learn those arguments second-hand by listening to other students' presentations. In addition to the philosophical readings that everyone would do together, each student would be assigned one empirical research task. Some might collect and crunch data; others might shadow teachers or interview school board members. They would all present their empirical research to one another. Finally, everyone would be required to complete an internship with one of our University's programs in the County schools, just to give the whole class basic sense of what the schools are like from the inside.

In subsequent years, new classes could either enhance the public website about our schools or move on to major new institutions, such as the police.

Posted by peterlevine at 1:48 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 9, 2005

"Imagining America"

I think that academics are pretty alienated--especially after last November, but the problem had been building for decades. Often, scholars feel very distant from the mainstream of American culture. In the social sciences, academics tend to be well left of the American mainstream; they also carry the burden of professional expertise, since they think they know good policies (or at least good reasons and evidence), yet political leaders ignore their findings. I have often criticized social scientists for believing they possess knowledge about values and about the future, when actually public opinion is just as legitimate. See, for example, this recent post. There is a good case for more genuine dialogue between social scientists and citizens, and Craig Calhoun of the Social Science Research Council makes that argument as well as anyone.

In the humanities, the problem is a little different. Most humanists don't believe that they could write a better budget than George W. Bush, or bring democracy to Iraq. They don't possess technical, analytical tools that give them confidence in their practical judgments and make them critical of foolish politicians and voters. However, they do feel very alienated from mainstream public opinion. Americans tend to be religious, pro-business, culturally traditional, and nationalistic, whereas most people who choose to teach and conduct research in the humanities are secular, critical of money and markets, culturally radical, and cosmopolitan. This gap seems to explain concrete, practical problems in their lives--declining enrollments in humanities courses, less financial support for research, fewer jobs, less fulfilling relationships with students. As Julie Ellison writes in a wonderful essay entitled "The Humanities and the Public Soul" (pdf), the "pressure is felt as coercive, as sabotage of the conditions needed for imagination and reflection."

Many of my colleagues assume that their main public role is to provide a critical alternative to mainstream culture--and to be subsidized by tax money and tuition for that purpose. It's a deeply uncomfortable position. Artists, by the way, are in the same boat, as I have argued in an essay entitled "Lessons from the Brooklyn Museum Controversy."

Ellison, whom I quoted above, is founding director of Imagining America, a consortium of 50 colleges and universities--including my own--that claim to be committed to "public scholarship."

Public scholarship joins serious intellectual endeavor with a commitment to public practice and public consequence. It includes• Scholarly and creative work jointly planned and carried out by university and community partners;

• Intellectual work that produces a public good;

• Artistic, critical, and historical work that contributes to public debates;

• Efforts to expand the place of public scholarship in higher education itself, including the development of new programs and research on the successes of such efforts.

Ellison promotes public scholarship as a way of overcoming alienation. Professors in the arts and humanities usually hold different political opinions from other citizens; they also struggle with the contrast between their critical stance and the public's need for hope and inspiration. As Ellison notes, conducting scholarship collaboratively and in public makes these tensions between academic and public values "more pronounced. But at the same time, public scholarship can bring these tendencies into a new and more fruitful balance." Scholars who collaborate with non-professionals can occasionally find inspiration and insight from that common work.

In another essay on the Imagining America website, Julia Lupton writes (pdf): "The crisis in the humanities--in public funding, in public interest, and in support on our own campuses--is our problem, not so much in the sense that we have caused it (there are multiple systemic factors at work), as in the sense that no one is going to fix it for us." It's almost always the case, no matter how unjust a situation may be, that political wisdom starts with recognizing that a problem is ours, that "we're the ones we've been waiting for." Imagining America has contributed a great deal by taking on the humanities' problems as its own and not being satisfied with blaming philistines and reactionaries for cutting budgets. At the very least, the organization has launched projects that would be deeply satisfying to work on.

Posted by peterlevine at 2:41 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 8, 2005

"Is Small Beautiful?"--the potential of alternative high schools

Rethinking Schools is an impressive publication, founded by teachers, dedicated to progressive reforms, and capable of attracting contributions by famous authors as well as excellent articles by educators who work "in the trenches." The current issue (not yet reflected on the website) is entirely devoted to the question: "Is small beautiful? The promise and problems of small school reform."

All the articles are stimulating, and there is so much to say in response that I expect to pick up several themes in subsequent posts. In fact, the issue is an excellent introduction to current "progressive" views of education in general, even though the explicit topic is small-school reform.

Several major urban systems are permitting lots of small schools to open, each with a strong and distinctive "theme." New York City plans to open 200 schools; Chicago, 100. Often, existing nonprofits jump at the opportunity to create schools that embody their own core values. For instance, in Rethinking Schools, Debbie Wei explains how an Asian-American civic group opened a charter school in Philadelphia's Chinatown:

We decided that if we were to build a school, it had to be a school that was consciously a school for democracy, a school for self-governance, a school for creation of community. We needed to build a school that was consciously anti-individualistic, anti-racist, anti-isolationist, and anti-materialist.

This is one kind of "themed" small school that's popping up. In her article, Michelle Fine notes that Philadelphia is also encouraging the creation of small "'faith-based' public schools" that collaborate "with Christian colleges and community organizations." Fine is not pleased. She says, "It breaks my heart to see the small schools movement ... used to facilitate ... faith-based education."

A lot of the impetus for the small schools movement has come from progressive people who are antiracist, anti-materialist, etc, etc. They want to create alternatives to mainstream schools that are further to the left. However, their strategy is to change policies so that nonprofits may open small schools; and inevitably conservative, religious, and pro-military groups (among others) are getting into the act. Reserving small schools for progressive nonprofits would be both unrealistic and unfair.

My own personal values are aligned with the Philadelphia Chinatown school (to a large degree), not with religious schools. But I see a fundamental parallel; each wants to motivate and inspire kids by promoting a rich and compelling philosophical message. That's putting it nicely. You could also say that both are sufficiently appalled by the power of mainstream culure that they are willing to indoctrinate kids to share their values. I'm enough of a classical liberal that I'd rather educate students in a more neutral way, to allow them to form their own opinions. For example, I wouldn't want to participate in an "anti-individualistic," "anti-materialistic" school. I'd rather teach multiple perspectives on ethics, including religious and libertarian ones.

However, there's a case for diversity of schools--for letting a thousand flowers bloom. But if we accept the value of diversity, then we must recognize that a lot of the "flowers" that sprout up will not be to our liking.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:47 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 7, 2005

resources on "trans-national youth activism"

One of the most interesting developments in youth politics and culture today is the rise of trans-national youth movements. The anti-globalization protesters and the student critics of sweatshops are the best-known examples, but there are many others. Typically, they are loosely organized; they make heavy use of the Internet, cell phones, and other new technologies; and they employ civil disobedience, boycotts, mass protests, and other tactics as alternatives to voter-mobilization and lawsuits (i.e., state-oriented political actions).

Many months ago, I attended a meeting on these movements, organized by the Social Science Research Council. The SSRC now has a useful web page with the papers that we discussed that day and other resources.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:42 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 6, 2005

a new era for public-interest advocacy?

I'm on my way home from Georgia, but still thinking about the conference of young media activists that I attended recently. For me, one of the most hopeful signs was their rejection of the "public-interest" model that first developed around 1970.

Thirty-five years ago, Ralph Nader, John Gardner, and their contemporaries founded a set of well-known organizations (led by Public Citizen and Common Cause) that later spawned second and third generations of similar groups. The innovations of that era also profoundly influenced established groups like the League of Women Voters and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. All these organizations cultivated the same constituency: liberal, largely White, highly educated, predominantly mainline Protestant and Jewish, and born on average around 1940.

The new "public-interest" groups introduced--and have continued to utilize--a set of political technologies: for example, computerized mailing lists that can be used to "alert" people at the grassroots and raise money for lobbyists inside the Beltway. The new groups also developed a common set of funding sources: namely, a total of maybe one million citizens who are willing and able to pay membership dues, plus grantmakers at a finite number of big foundations--many of whom came originally from the Nader-style activist groups.

These groups have developed a similar rhetorical style, which tends to depict "American citizens" as victims of wealthy corporate interests. "American citizens" are understood as a single population with a "common cause," whose interests equal the "public interest." Finally, these groups have overlapping goals. They seek stronger and more independent expert regulatory agencies at all levels of government; more judicial oversight of the executive branch; more political power for women and minorities; more legal protection for civic liberties; and more spending on social programs.

All of this, I believe, is now in shambles. The "public-interest" constituency is getting old and is not being replaced. The few interested foundations cannot provide sufficient money, yet they exercise too much leverage on the movement because there are not enough alternative sources of funding. The technologies of mobilization don't work in today's noisy environment, when everyone else is also "alerting" reporters and trying to make citizens mad. Besides, mobilizing people doesn't sustain their interest or tap their knowledge and talent. Both the Beltway lobbyists and the people who pay their salaries are overwhelmingly White and middle class. That is not only unfair; it's also politically damaging for a liberal movement.

Finally, and most profoundly, the goals of the public-interest movement no longer make sense--and even the participants no longer really believe in them. Regulatory agencies always get captured by special interests. In any case, expert regulation is too centralized and "top-down." Judicial oversight is not a reliable tool for liberals if many judges use "original intent" or cost-benefit analysis to interpret the Constitution. Even if judges are liberal, the judiciary will simply become a target for populist anger unless liberal ideas have a broader constituency. Increased social spending won't help if institutions, such as urban school systems and police departments, are profoundly flawed internally. And even when liberal elected leaders have power and are able to distribute goods, rights, and services, the results are not always so great.

For example, during the conference, we watched a sample documentary movie made by a citizens' group and presented by Scribe.We viewed the video as an example of citizens' media, but the substance of the film was interesting, too. According to the documentary, the city of Philadelphia has been seizing private homes in established, working-class neighborhoods so that those areas can be redeveloped according to the city plan, without consulting property-owners or communities. The video reflected just one perspective, and I'm sure the case is more complicated. Perhaps the city plan is wise; or perhaps it is a bad plan, but the city government is being manipulated by powerful corporate developers. It is also possible, however, that a Democratic administration that happens to be led by an African American insurgent mayor is using governmental power to trample individual property rights. That is hardly a paradigm case for the left. Friedrich Hayek sounds like a more relevant analyst than Karl Marx.

All this means that we need to new ways to address social injustice without necessarily relying on an activist state. And today's young lefties, with their fluent use of new technologies, their hunt for independent funding sources, their deep embrace of diversity, and their enthusiasm for "free culture," may be just the people to develop the new strategies we need.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:53 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 3, 2005

what's going on at the office

Every now and then, I post a summary of what's going on in my work life. These summaries seem worthwhile, since often people email me to ask practical questions connected to what I've written. So here goes ...

CIRCLE has been basically operating for the last two years on large grants from The Pew Charitable Trusts and Carnegie Corporation of New York. Both grants expire at the end of this month. However, we have pending grant proposals that, if approved, will carry us for another two years. I have been working hard on those proposals. We are also trying to diversify our funding, both for financial reasons and to allow us to move into other subfields. For instance, we are working with an excellent colleague in our College of Education to develop a large research project on the effects of studying history and civics at the early grades. We hypothesize that studying those subjects will help students to perform well on standard, "high-stakes" reading assessments. In all, we have 11 proposals either pending or in development.

CIRCLE will be searching for two new full-time people. I can't post the job descriptions until the University approves them, but we will be advertising shortly.

One of CIRCLE's jobs is to analyze youth voting statistics. Until last week, we could only use exit poll data for 2004; and exit polls have certain limitations and flaws. Last week, the Census Bureau suddenly released its November 2004 survey, which asks questions about voting. My CIRCLE colleagues (without much help from me), quickly crunched the numbers and produced new turnout data based on the Census. The story is basically the same as what we have been saying since November, although it actually looks slightly better for youth. They didn't just keep pace with the overall turnout increase; they surpassed it. See this pdf for details.

CIRCLE also released a major new study of service-learning this week. ("Service-learning" means a combination of community service and academic work on the same topic.) The study finds that service-learning does not compete with rote, boring social studies. The teachers who don't use service-learning often employ other interactive and creative techniques, such as debates and research projects. On average, service-learning produces about the same results as the alternatives. But there is greater variation among the service-learning classrooms, with some doing much better than average and some much worse. This is the pdf.

We are planning a major public meeting at the National Press Club to examine the potential of high school reform for civic education. The date is July 6, and everyone is welcome to attend. We will post a full agenda soon. In the meantime, you can email dsapienz@umd.edu to reserve a spot in the audience.

As I mentioned on Tuesday, I'm working with 11 undergraduates who are in residence for the next six works and being paid for 180 hours of community research. Their results will feed into the Prince George's Information Commons website. They are supposed to present plans for their summer today. Meanwhile, high school students are working on a video documentary about nutrition in their immigrant community, but I haven't been seeing them regularly--three excellent grad students have been managing that work on my behalf.

The Deliberative Democracy Consortium will hold its annual "researchers and practitioners meeting" in Washington in two weeks. I'm on the planning committee and will also help to present some research results based on interviews of activists from the developing world.

Posted by peterlevine at 8:00 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 2, 2005

why the commons is not for communists

"The commons" is composed of our shared assets: the earth's atmosphere, oceans, and water-cycle; basic scientific knowledge (which cannot be patented); the heritage of human creativity, including folklore and the whole works of Plato, Shakespeare and every other long-dead author; the Internet, viewed a single structure (although its components are privately owned); public law; physical public spaces such as parks and plazas; the broadcast spectrum; and even cultural norms and habits. Some of us believe that protecting and enhancing the commons is a central political task of the 21st century. For different flavors of that argument, see, for example, OnTheCommons, The Tomales Bay Institute, and Lin Ostrom's workshop at Indiana.

I have suggested that enhancing the commons might be a strategy for increasing equality. If that strategy belonged to the radical left, I would not hesitate to embrace it. However, I don't think that it has much to do with traditional leftist thought. It is worthwhile to distinguish the theory of the commons from Marxism, just for the sake of clarity. I see several fundamental points of difference.

The commons is not state-centered. Some common assets are completely un-owned (e.g., the ozone layer), and some are jointly owned and managed by associations. Some belong legally to states and are controlled by them: think of Yellowstone. However, it is by no means clear that states are ideal--or even adequate--owners of commons. I realize that some Marxists have also been skeptical of the state--including perhaps old Karl himself, who wished that it would wither away. Nevertheless, a major current in Marxism has been statist, and the commons isn't.

The commons is only a part of a good society, not the whole. Some anarchists want everything to be treated as a common asset, but most of us simply value the common assets we already have and want to protect them against corporate "enclosure," over-use, and other threats. We have no interest in abolishing either the state or the market; on the contrary, we think that both work better if they can draw appropriately on a range of un-owned assets, from clean air to scientific knowledge.

The commons supports "negative liberty." Isaiah Berlin famously contrasted the absence of constraints ("negative liberty") from the capacity to do something ("positive liberty"). For example, the First Amendment gives us negative liberty by removing the constraint of censorship, but we don't have positive freedom unless we own a newspaper--or a website. Marx's own ideas about liberty were complex and perhaps ambiguous. But most Marxists have believed that positive liberty is more important than negative liberty--or have even dismissed the latter as a snare and a delusion. Although a commons may enhance positive liberty, what it most obviously provides is negative liberty. If something is un-owned, then there is no legal constraint on our using it. This is both the beauty of a commons and its weakness. The commons, if anything, is a utopian libertarian idea rather than a Marxist one (although some libertarians have forgotten that they are inspired by freedom, not by markets).

The commons is not (literally) a revolutionary idea. Preserving the commons may take radical action at a time when the oceans are being depleted, big companies are privatizing the software that underlies the Internet, and scientific research is being diverted to produce patented products. However, I don't think we need fundamentally different national institutions from the ones we have today, and therefore I see no need to upset our polity. On the contrary, we ought to revive old and powerful traditions that support the commons. At the global level, I suspect that treaties and trans-national popular movements will be sufficient to protect the commons; there is no need for anything like a global state. It is good that we don't need revolutionary political change, because revolutions almost always go wrong and destroy what they set out to promote.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:53 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack