« May 2004 | Main | July 2004 »

June 26, 2004

gone until July 12

I'm going to Europe tomorrow, for two weeks, and I won't have Internet access. That's a choice rather than a technological necessity: I need a brief break. So no posts until July 12, but I hope you'll come back then.

The trip, by the way, is mostly fun--a family vacation in London and Burgundy. But I'll also be at the University of Sussex/Institute of Development Studies for four days. It promises to be a really interesting visit, and I'll report on it in July.

Posted by peterlevine at 5:00 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 25, 2004

what's going on at the office

We just signed a contract to repeat a national survey of young Americans that was last conducted in 2002. It's a broad assessment of young people's civic and political engagement, not narrowly focused on voting and political opinions. Repeating the survey will give us a chance to update our numbers and also to analyze the young population in some detail.

CIRCLE has recently created a nice online interactive map that shows youth voting statistics by state.

Jim Youniss of Catholic University and I have been awarded a Carnegie Foundation grant to pull together a scholarly group that will try to bridge the gap between developmental pyschology and political science. Psychologists know a lot about how the political system makes people into active or alienated citizens; but they tend to be ahistorical. They talk about "politics" or "government" in general, and don't consider how (and why) politics has changed. Political scientists know all about the changes in our political system, but they rarely consider its impact on political socialization. Jim and I are charged with trying to fill that gap.

Earlier this week, I watched videos of two focus groups: teachers in Portland, OR and parents in Cleveland, OH. These focus groups had been commissioned by the Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools, which is an advocacy coalition dedicated to implementing the recommendations of the Civic Mission of Schools report. An important first step is to find out which arguments for civic education (broadly construed) are most effective. It was odd (and, frankly, something of an ego-trip) to watch strangers 3,000 miles away being read passages from a report that I had helped to write. Generally speaking, the teachers were very enthusiastic about it. One teacher said, "It's hard to imagine what else [anyone] could come up with." They all endorsed the idea that schools have a civic mission. They were also very knowledgeable; in conversation, they referred to service-learning, the Center for Civic Education, Deborah Meier, and even Paul Wellstone's Civic Education Enhancement Act. They were leery of additional tests in social studies--but so am I. Predictably, the parents' group was much less knowledgeable and enthusiastic. As one of the teachers said: If you ask parents whether schools have a civic mission, they will agree, because they know it's the right thing to say. But they really want their own kids to get an education that will help them to get ahead; "civic education is for other people kids."

Posted by peterlevine at 12:13 PM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

June 24, 2004

two definitions of "public intellectual"

I'm interviewed in the latest issue of a journal called Higher Education Exchange. Actually, David Brown conducted simultaneous email interviews of me and of Bob Kingston, a senior associate of the Kettering Foundation, and edited our comments together (with our help). I'm not sure how coherent the whole document is. I would summarize it as follows:

Bob admires "public intellectuals" who have broad interests, address crucial and current public issues, and reach large audiences. I admire those people too, although I think they are already well supplied and rewarded. Besides, Learned Hand had a point when he warned: "You cannot raise the standard against oppression, or leap into the breach to relieve injustice, and still keep an open mind to every disconcerting fact, or an open ear to the cold voice of doubt." In other words, there's a tradeoff between impact and intellectual rigor.

Therefore, I especially admire a different kind of "public intellectual," one who gets deeply enmeshed in the work of institutions or communities, contributing his or her skills and knowledge but also constanrly learning from experience and feedback. Such scholars may never talk to large audiences about broad issues. On the contrary, my favorite "public intellectuals" are self-effacing, listeners rather than talkers; and they focus on relatively narrow or local issues because those are what concern people. Because they take the time to understand the complex details of local problems, they risk losing the chance for fame and influence.

By the way, these lists of famous "public intellectuals" are interesting. They do not include the kind I admire. (Thanks to Hellmut Lotz for the reference.)

Posted by peterlevine at 1:14 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

June 23, 2004

get me Reilly

Apparently a real politico named Reilly (I was told--but forgot--his first name) once explained that a successful Washington career has the following stages:

1. Who's Reilly?

2. Get me Reilly!

3. Get me a Reilly.

4. Who's Reilly?

The goal is to reach stage 2 early, and then stay there as long as possible.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:02 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

June 22, 2004

social programs, as seen by the press and by blogs

I'm still brooding about Sunday's New York Times Magazine article on Harlem Children's Zone (see my previous comment). HCZ is a nonprofit that provides a wide range of services to most of the kids in Central Harlem. City governments often provide similar combinations of services for their residents. But governments always fail, whereas HCZ is successful--right?

Actually, there is very little outcome data available for HCZ. I cited the test scores of kids leaving its preschool program, because these data are listed on the HCZ website (see this report, p. 5). There are a few other outcome measures in the same document. For instance, the rate of health insurance coverage rose from 95% to 97%. This is not exactly earth-shattering. And most of the other data in the report concern "performance" rather than "outcomes": 1,982 children were screened for asthma, 2,150 books were "made available," etc.

Any municipal government could assemble much longer lists of this type and also cite compelling "outcome" measures for some of its programs. So why does HCZ rate a cover-story in the Times Magazine? Perhaps ...

The point of this list is not to criticize Harlem Children's Zone, nor am I interested in arguing that local governments do a better job than is generally recognized. In my own thinking, I have incorporated the assumption that traditional welfare programs and schools are largely broken, at least in the inner cities. My concern, therefore, is not ideological but epistemological. I am worried that we do not have reliable ways to understand the performance of local governments, whether they work well or badly. Even people who specialize in social policy must rely on middle-brow publications like The New York Times for a general picture of what's going on across the whole range of social issues. And such publications generally do a poor job in describing and assessing all social programs, but especially those in the public sector. They mainly cover public agencies when officials are indicted, sued, or otherwise enmeshed in the legal system, because reporters have easy access to police and court records. Insightful stories about day-to-day work in local government are extremely rare. And again--I don't want more good news, just more substance.

Everyone now recognizes the failures of the mainstream media, and many people hope that the Internet will fill some important gaps. In particular, one would expect that left-of-center bloggers would rush to describe the government programs, nonprofit associations, social movements, and unions that are usually overlooked in major newspapers. They would want to report good news, because they have an interest in countering the dominant assumption that government programs always fail. And they would would want to report failures, because they have an interest in creating better programs. However, there is very little such reporting in the "blogosphere."

I can sometimes get the attention of the Web's big guns if I opine on political philosophy in relatively general terms. Such editorializing can get me mentioned on Volokh, Crooked Timber, the Decembrist, or Matthew Yglesias. But when I write about day-to-day social work, such as this interesting experiment in municipal government in Washington, no one in the blogosphere seems to notice. Clearly, the reason could be my lack of reportorial skill; I'm no journalist, and I don't know how to make these examples vivid. However, the important question is not about me; it's about the whole range of leftish blogs. Where are the Web-based chroniclers of the public sector? Who's visiting charter schools and telling us how they work? Who's reporting from welfare offices and health clinics? I would trade a hundred pages of rants against George W. Bush for one site that kept me informed about what works and doesn't work "on the ground" in our inner cities.

[Added on June 25: Anna (in a comment) links to "Respectful of Otters, a blog that reports from the frontlines of social work. I'm sure there are other examples.]

Posted by peterlevine at 10:30 AM | Comments (11) | TrackBack

June 21, 2004

listen to Bill

Bill Galston is my boss (and friend). Therefore, I got a big kick out of Kenneth Pollack's article in The New Republic, entitled, "Mourning After: My Debate with Bill Galston." It begins thus:

Bill Galston is one helluva debater. In the fall of 2002, well before the invasion of Iraq, I faced Bill--a University of Maryland professor and a former colleague of mine in the Clinton administration--in a public debate, and he kicked my rhetorical ass. He did it by holding up a copy of my book, The Threatening Storm, and saying to the audience, "If we were going to get Ken Pollack's war, I could be persuaded to support it. But we are not going to get Ken Pollack's war; we are going to get George Bush's war, and that is a war I will not support." Bill's words haunted me throughout the run-up to the invasion. Several months ago, I sent him a note conceding that he had been right.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:45 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

June 20, 2004

Harlem Children's Zone

Yesterday's New York Times Magazine has a fairly compelling cover story about the Harlem Children's Zone (HCZ) and its founder, Geoffrey Canada. I don't have a lot of confidence in the Magazine as an evaluator of social programs. Evaluation is a tricky business, and the Magazine is too focused on personal profiles and anecdotes to be a reliable source. However, it is a good guide to what is currently influential. Marian Wright Edelman and William Julius Wilson are quoted in praise of HCZ, which tells us that important people are watching the program.

Mr. Canada hopes to make a huge difference in the lives of 6,500 Harlem kids for about $4,200 per child per year. If that can be done, then we have no excuse for not doing the same for all poor Americans.

HCZ asserts that 100% of the students in its pre-K classes test as ready for school at the end of the program, compared to a rate of 84% for all American kids. One might suspect that HCZ students are relatively well off to start with, since their guardians have placed them in a voluntary program. In that case, the 100% readiness rate might be a function of the population rather than the program. However, the Times story emphasizes that HCZ works relentlessly to sign up the most disadvantaged children in Harlem. If that's true (and if the "Bracken Scales of Conceptual Development" are a good measure of readiness for school), then a 100% pass rate is impressive indeed.

HCZ also organizes classes for mothers, afterschool and tutoring programs in public k-12 schools, employment placement services, nutrition services, neighborhood beautification efforts, an asthma clinic, and family crisis counseling. It has recently launched a charter school. In one way or another, its services reach 88% of the kids in Central Harlem.

I can't quite figure out what's most significant about the enterprise as a whole: that one institution is providing services to most children in a large urban district; that the institution is a nonprofit with corporate donors, rather than a municipal agency; that its services span health, education, and other fields; that there's a deliberate effort to reach the worst-off within the ghetto; that the nonprofit has a corporate-style business plan and collects a lot of data; or that Geoffrey Canada is a skilled, committed, and effective individual. We can't clone Mr. Canada, nor is there enough corporate philanthropy to fund private non-profits on this scale in every city. I hope, therefore, that HCZ is successful because of factors that could be borrowed by local governments.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:02 PM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

June 18, 2004

home rule for Baghdad

A reliable friend gave me a professionally printed document entitled "The Law of Home Rule of the City of Baghdad: Enacted by the Baghdad City Council on Behalf of the Citizens of the City of Baghdad" (Draft, June 2, 2004. Adopted: ______ 2004). I cannot find this document with a Google search, but it looks genuine, and it's interesting on several levels.

First, style. The preamble seems to have been written by Baghdadis: "In the Name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate ... Treasuring the many wonders of our unique City, recognizing that Baghdad has served as the [sic] cultural and educational center of the world and has a future as one of the world's greatest cities ...." The mayor or city manager is called an Amin, and his administration is the Aminate--in a nod to Arabic. However, many portions of the main text appear to have been borrowed verbatim from US boilerplate. For example, there's a "severability clause" at the end to ensure that the rest of the charter will remain in force if any part is struck down by a court. Other clauses sound to me like the work of US advisers who are trying to explain the document in lay terms. For example: "This Charter specifically does not set forth all the powers that may be exercised by the District Councils." This doesn't sound like legalese to me. I can imagine a nervous non-lawyer adding it to make sure that the District Councils are not overly limited.

Moving to substance: the charter basically creates a city manager system, on the model pioneered in America during the Progressive Era. All power is vested in an elected council that hires a professional Amin with considerable authority; he (or conceivably she) serves at the council's pleasure.

The city has home rule, but its independence is somewhat exaggerated. For example, one of the city's "authorities" is the police, but it turns out that Baghdad can only "consult and advise the Provincial Council and the Ministry of the Interior regarding requirements for adequate law enforcement services." The city doesn't actually run a police force.

In addition to the citywide council, there are to be District Councils and Neighborhood Councils. The District Councils can propose legislation (which must be voted in the City Council), they may review all appointments by the Amin, they may propose budgets for capital improvements, and they may be given additional powers. This sounds like real power to me. The Neighborhood Councils can propose legislation and are guaranteed a regular opportunity to see the city's annual report, budget, and plan. That is not a major allocation of power, but it may increase transparency and participation at the neighborhood level.

I'm not one to exaggerate the importance of constitutions, charters, and other pieces of paper. Political culture is more important, and it's hard to know whether the norms assumed by this document are realistic or appropriate. I'd love to know more about how it was written and what Baghdadis think of it.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:11 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 17, 2004

chalk talk

I'm not a big fan of elaborate facilitation techniques, but I've had two good recent experiences with a method called "chalk talk." Here's how it works. You write a few significant and relevant words on a large expanse of paper or a blackboard. You distribute markers or pieces of chalk to everyone in a group. You tell them that there are only two rules: 1) No talking. 2) It's over when it's over.

There is then a brief period of embarrassed silence until someone writes a word or phrase (or possibly draws a picture). Others join in. They pose questions silently and draw lines connecting other people's ideas. Everyone concentrates intensely, the board fills up, and then the pace slows. Finally, you say, "It's over."

This is an efficient way to get lots of comments "on the record." It would take hours for people to say the same things in a standard conversation. The method encourages everyone to pay attention to everyone else's thoughts. It can empower shy people to participate from the beginning. And it's a good way to think about connections and disagreements.

This page shows the results of a "chalk talk" exercise from last week, at which social activists from eight countries silently discussed "participation" and "deliberation." (To see the whole thing, scroll right and down.) I'm not sure that the image makes much sense unless you were there, but it's a good conversation-starter and a great resource for anyone who wants to summarize a meeting (in a more linear style) afterwards.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:01 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 16, 2004

geographic information systems (GIS) in civic ed

Yesterday was our last class at the high school for this academic year. We brought along some maps (based on data that the students had collected) that showed aspects of the community that may affect young residents' health. In particular, the maps show that kids who walk are clustered in certain areas; thus some neighborhoods may be built in ways that are friendly to pedestrians. That would be an important finding, because we know that walking reduces obesity, and obesity is a big health problem. Our students are alert to possible causes of error (the small sample, selection bias, hidden causes, etc). We would have to do a lot more research before we could draw any rigorous conclusions.

Today I took an excellent intermediate-level class on GIS software and became increasingly excited about what we can do with the class when we resume next fall. We'll certainly ask them to collect more data about their fellow students' behavior and locals assets such as stores and parks.

It's exciting to address an issue (obesity) that's usually seen in strictly pyschological terms--as a matter of body-image and will-power--and to look instead for geographical causes. Active citizens can potentially change the local landscape and zoning laws, whereas body-image and eating habits are very hard to change. Meanwhile, GIS software is making it possible for kids who don't have very advanced skills to understand their environment in tremendously powerful ways.

Posted by peterlevine at 9:44 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 15, 2004

Hobson-Jobsonism in Brazil

A hobson-jobson is my favorite linguistic phenomenon. A good example is "compound," which originally meant any union of several elements. English visitors to what's now Malaysia encountered the Malay word "kampong," which meant a group of buildings enclosed by a wall. They heard "kompong" as "compound," and gave the English word that new meaning. Another example is "gas." The Dutch chemist van Helmot used the Greek word "chaos" to refer to substances that acted like steam. English scientists misheard him and thought he was saying "gas."

On my way to Georgia last weekend, I happened to be seated next to a Brazilian colleague whom I had met at the conference last week. He asked me how long it takes to get to the "finger" at Atlanta's airport. It turns out that the English word "finger" is what Brazilians call the gates at airports (which do look like fingers reaching onto the asphalt). He understandably assumed that this metaphor was borrowed from English, but it's an imaginary borrowing--a kind of hobson-jobson.

The phrase "hobson-jobson" itself arose when English imperialists in India heard their Muslim subalterns chanting "Ya Hasan! Ya Husayn!: O Hasan! O Husain!" In their offensive way, they called this chanting the "natives' hobson-jobson." Question: Is the phrase "hobson-jobson" (referring generally to misunderstood words appropriated from foreign languages) itself a hobson-jobson?

Posted by peterlevine at 11:09 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 14, 2004

libertarianism and socialization: replies

(Written in Macon, GA): It's amazing how a comment about libertarianism draws more attention than almost anything else in the "blogosphere." In a post from last week, I argued that libertarians ought to be concerned about how parents and communities raise their kids, because most people are not raised to value individual liberties as highly as libertarians would want. I also expressed some openness to pragmatic libertarianism while rejecting a pure philosophical form of the ideology. This post provoked comments on my site, in my email inbox, and on the Crooked Timber site, thanks to a nice mention by Kieran Healy. I'd like to respond to several of these comments together:

1. I predicted that people who grow up in communities that bar public displays of political opinion will lack respect for the First Amendment. How do I know this?

I don't. In theory, raising kids in speech-free zones could provoke a reaction: the next generation could passionately embrace political debate. It's always hard to predict the effects of social arrangements on political beliefs. This is one good reason not to use state power to manipulate private choices. (The other reason is liberty itself.)

However, it seems at least plausible that the next generation will lack respect for free speech if we raise many of them in affluent and well-ordered communities that deliberately banish signs, leaflets, and canvassers. If I were a libertarian, I would worry enough about this that I would want to collect data on the attitudes of young residents of homeowners' associations. I might also launch a rhetorical campaign to support libertarian associations--those that choose to allow (or even to encourage) public displays of free speech.

More generally, adults' political attitudes and behaviors are heavily influenced by their parents' political views and actions. Of course, there are exceptions: people who renounce the party or ideology of their parents. Libertarians are often examples, since libertarianism is a rather contrarian philosophy. However, the statistics are clear: parents' beliefs correlate very strongly with children's beliefs. We don't choose our parents, yet their beliefs tend to influence our choices for the rest of our lives. This is a conundrum that ought to provoke more thinking in libertarian circles.

2. How important is a ban on political signs and canvassers? After all, neither form of political "speech" is common anywhere. Maybe in walled communities, campaign signs are banned, but everyone is inside checking out political websites. Then the ban would do no harm.

This is a good point and a source of some consolation. Nevertheless, I worry that an explicit and deliberate ban on a certain kind of speech sends the message that such speech is socially undesirable. Why shouldn't people be able to put up small signs with political messages? Why does banning such signs seem to increase property values?

3. "Bill" points out that if we are pragmatic libertarians (who embrace markets only when they work better than governments), we need a method for deciding when to embrace market solutions. One method is exactly what I favor: "have a big public argument and then let politicians decide (subject to any discipline voters place on them by voting them out)." Bill adds: "This ... has problems. Politicians often do not have proper incentives to decide the right way even for the x for which there is a big public argument. ..."

I agree that politicians have incentives to make the wrong decisions, and a "big public argument" can turn out badly. (Among other things, it can turn into majority tyranny.) However, it seems clear to me that markets work for some things and not for others. They don't provide national defense, finance universal education, protect the ozone layer, etc. I don't believe that any existing social theory can tell us when they work and when they don't, because success is a normative matter, not a scientific one. Therefore, we must have a "big public argument" followed by a decision by our elected representatives. This is a flawed process and not one that can be perfected; but it can be improved. We have an array of safeguards to employ, starting with the Madisonian toolkit (checks and balances, a free press) and moving to more radical ideas (decentralization and subsidiarity, citizens' deliberations).

4. I said, "I believe that human beings may make claims on others for economic support; that some of these claims are morally obligatory..." Craig asks, "I for one would like to hear(see) those claims made; offhand I can't think of any that I'd be persuaded by, excepting familial claims."

I think most Americans would agree with me that when we are born, helpless and ignorant, we deserve at least an affordable education through the 12th grade, protection against abuse by our own parents, shelter and nutrition, protection against crime and foreign invasion, and basic health care. If we have rights to these things, then someone has a correlative duty to pay for them. Parents certainly have the primary duty, but many cannot afford education, housing, and health care for their children. Some might say that it is wrong for them to have children, but it happens, and it's not the kids' fault.

Why should citizens of a person's nation pay the difference between what his parents can afford and what he needs? Why doesn't the obligation apply to all citizens of the world, or only to the local neighborhood? There is no a priori argument that nation-states ought to provide safety nets, but we do have some positive experience with states that do so. By far the highest standards of living ever attained in human history exist in democratic states that guarantee a package of social services: the United States and its allies in North America, Western Europe, and East Asia. It would take a very strong argument in favor of a different political unit before I'd want to reject the social contract that has made Norway, Australia, Japan, the US, and similar countries such extraordinarily good places to live.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:14 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

June 11, 2004

deliberation and advocacy

Rose Marie Nierras (of the University of Sussex) and I conducted a kind of focus group today. The participants were activists from the United States, Canada, the Phillippines, India, Brazil, Mexico, South Africa, Sweden, and Denmark. Rose and I have been studying how deliberative democracy looks to people who work in social movements, especially in the developing world. This was the fourth and final day of the Deliberative Democracy Consortium/LogoLink meetings, and Rose and I have been interviewing the participants individually. Today's group discussion will give us additional data; and we will conduct several more such events in several countries before we finish the project.

We are not ready to digest our results so far, but I have a few stray thoughts: It's more difficult to mobilize lots of people for procedural reforms than for specific social causes--except when there is a dictator in the way of social progress, in which case "democracy" becomes a rallying cry. It's easier for social advocates to embrace democratization if they believe that their cause is supported by a large majority of their fellow citizens. It's harder to disentangle social causes from democratic reforms in new democracies than in "mature" ones.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:24 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 10, 2004

Basilica of Notre-Dame, Montreal

I'm still with the Deliberative Democracy group, with no time to blog, but I wrote the following several days ago ....

Last week, I was in Montreal for four days. There was plenty of unscheduled time, so I walked for hours each day. Montreal is an impressive and lively city. I don't write travelogues on this blog, but I would like to say a few words about the Basilique Notre-Dame. This must be one of the best Victorian buildings in the world—and there are many. Some Victorian buildings are either unimaginative imitations of medieval models or damaging renovations of actual medieval structures (or both). In contrast, the Basilica is a highly original Gothic building constructed on open land in the New World. It resembles a great Victorian train station, museum, or exposition hall more than a medieval cathedral.

Most of its components derive from medieval architecture—specifically, the French High Gothic of the Ste. Chapelle in Paris, which is the acknowledged inspiration. The arches are pointed, the columns have gothic capitals, the windows are filled with stained glass, and there are scores of life-size sculptures of saints in medieval garb. (An exception is the huge pulpit, which is reached by a broad, winding staircase that's more baroque than medieval in inspiration.) However, the overall appearance of the building is not at all medieval; it's highly original. This is partly because of specific architectural choices. For example, there are rose windows in the ceiling of the nave, which would have been impossible and unimaginable in the 13th century. Also, the nave is proportionally wider than any medieval one I've seen, perhaps because Victorian construction techniques allow a wider span. Quite apart from technological issues, I suspect that medieval builders would have preferred a loftier but narrower shape.

I have never seen a medieval church (not even Ste. Chapelle or the lower church in Assisi) that is as heavily decorated. Every single surface of Notre-Dame is covered by stained glass, tile, statuary, or high-relief sculptural decoration that's also painted with zigzags and other bold patterns in dark primary colors. There’s virtually no unpainted stonework. This all sounds terribly busy or even vulgar. However, the patterns are small and the overall structure is simple and easily legible. As a result, the surface patterns make a restful impression. Finally, all the patterns and other decorative features are symmetrical—the result of a single plan—whereas most medieval buildings are more organic (or haphazard).

If you look at the details of Notre-Dame, many are not very fine. The figures in the stained glass (from Limoges, France) are much larger and coarser than anything medieval. However, the building as a whole is unusual, interesting, and worth a long trip to visit.

Posted by peterlevine at 4:00 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 9, 2004

community government in Washington

I’m still at meetings of the Deliberative Democracy Consortium, but we’ve now been joined by a diverse group of activists from developing countries (members of the LogoLink network). We’ve gone on a “field trip” to the Southeast quadrant of my own city, Washington, DC. We’re sitting in a cheerful, well-equipped, modern building in a diverse but basically very poor district. In the city’s Seventh Ward, there’s a low median income, high crime, and a disproportionate number of children and senior citizens, although there is also a high rate (40%) of home-ownership.

We are observing a public meeting of officials representing nineteen municipal departments. Their job is to develop comprehensive solutions to “persistent problem areas,” such as outdoor drug markets at specific locations. A solution might involve the police (who would make arrests), the department of Public Works (which would tow away abandoned cars), housing agencies (which would build infill housing in abandoned lots), the Fire Marshal (who would fine landlords), the park service (which would cut down overgrowth), and others. Each neighborhood in the city has a similar team to coordinate municipal departments and to encourage citizen population.

The work that we are witnessing today is nested within an ambitious and impressive process for public participation. The City of Washington now convenes regular Citizen Summits at which thousands of residents deliberate about the Mayor’s proposed budget and strategic plan. Demographically representative samples of the city’s population meet for a day in the city’s huge Convention Center and use electronic technology to pool their ideas (a process developed by America Speaks). This discussion has a substantial impact on Washington’s priorities. Specifically, it has caused some redistribution of funds and priorities. As they deliberate, people from wealthy districts realize that the needs are greater in the city’s poor areas, and they come to support redistribution.

The Mayor then develops a contract with each city agency to implement the strategic plan. Performance can be monitored easily online, because agencies commit to tangible targets: e.g., “put 200 more officers on the street.” Finally, a team is convened in each neighborhood to develop a strategic plan for their more local area. City departments send representatives who are experts on the particular neighborhood and empowered to make decisions on their departments’ behalf. We are witnessing a weekly meeting of one such team.

This meeting is interesting to me because I was recently at a libertarian conference at which government was described as inefficient, corrupt, and unresponsive. There were calls for radical decentralization. The main approach that we discussed was to allow private individuals to band together into voluntary groups and purchase services on the market (i.e., privatization). Libertarians argue that they are not anti-political or anti-democratic; in fact, they want more intense and meaningful public participation, and they believe that voluntary associations are most hospitable to democracy. They blame central planners and other government experts for squelching public participation, localism, and pluralism.

Today I am witnessing decentralization and participation within the public sector, as ordered by a big-city mayor. I don’t have enough information to be able to say which approach works better, but I would recommend a certain amount of openness and pragmatism. There may not be a fundamental difference between libertarian and left-liberal approaches to participation. We happen to be meeting in the offices of a Community Development Corporation (a private nonprofit), which operates with government funding but is thinking of selling its services for fees. It has convened city employees to discuss how to coordinate their powers to make arrests, condemn buildings, and otherwise act as Leviathan.

In short, this is a public-private hybrid, in the great American tradition. Strong democrats might see it as an example of creeping privatization and the imperialistic market; libertarians might see the heavy hand of the government and the taxman. I think we’re witnessing participation, accountability, and pluralism.

Some observations about the meeting itself:

Posted by peterlevine at 8:28 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 8, 2004

Deliberative Democracy Consortium

All day today, I'll be participating in Steering Committee meetings of the Deliberative Democracy Consortium, so I don't anticipate being able to write anything here.

Posted by peterlevine at 7:37 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 7, 2004

public-interest groups and communications policy

I'm delighted to announce that a student of mine, Tina Sherman, passed her dissertation defense today. I don't want to "scoop" Tina by revealing her findings. However, she interviewed about two thirds of the leaders of all the self-described "public interest" groups that work in the fields of communications and information technology. These are the groups that lobby or litigate--ostensibly in the interests of the public--on issues like the number of TV stations that a company can own, the availability of licenses for local, "low-power" radio stations, the basic rules governing the Internet, the number of years that copyright protection lasts, and the amount of money that we spend equipping schools with computers. Tina also interviewed several foundation executives who fund these advocacy groups. Her research portrays one fairly typical subset of the "public interest community," roughly 30 years after Ralph Nader, John Gardner, and their peers created the first of these groups. The results are important and troubling.

Posted by peterlevine at 5:29 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 6, 2004

thoughts on libertarianism

Since I’m at a Liberty Fund conference with several libertarians, I’d like to make two comments about this ideology:

1. I’m open to pragmatic but not philosophical libertarianism: If you come at me with a coherent and radical version of libertarianism, I will resist it. In contrast to libertarians, I believe that human beings may make claims on others for economic support; that some of these claims are morally obligatory; and that governments may enforce such claims through taxing and spending. I don’t see a tax as an immoral “taking” of sacrosanct private property. This is only one place where I part company with abstract libertarian theory.

However, libertarians have also developed a whole set of pragmatic arguments to accompany their core philosophical beliefs. They say that governments tend to fail at their own explicit purposes, are often captured by special interests, and promote upward economic redistribution; and that markets work better. Libertarians often assert that these arguments must apply in all (or almost all) circumstances. They rely on fundamental theoretical reasons that derive from economics, not philosophy—for example, the idea that markets efficiently deliver what everyone demands. I think, in partial contrast, that market solutions often work in particular domains and are worth testing. In practice, this means that I am open to, and interested in, libertarian arguments that take the form, “A market will solve problem x” (where x is something like poverty, crime, or environmental degradation). Pure philosophical libertarianism, however, says, “We shouldn’t structure the ground rules of society in order to solve problems of this type; we should simply respect private individual liberty.” I disagree with this formulation, but that doesn’t prevent me from learning practical lessons from libertarianism.

For example, my colleague Bob Nelson is a libertarian who has argued for a long time that cities ought to grant all their zoning power to neighborhood associations. I can imagine granting such associations the right to buy garbage and sewer services on the open market; and the right to operate charter schools. Local police precincts could also be made accountable to the same associations. I suspect that in poor neighborhoods, people could do better for themselves than the city government can do for them. I’m not positive that this is a libertarian position, but whatever it is, it’s well worth a try.

2. Libertarians should be much more concerned than they are with political socialization: For well over a century, libertarian authors have been arguing eloquently for a minimal state. Yet most Americans favor Social Security and Medicare, oppose drug legalization, and are even lukewarm about the Bill of Rights. What’s gone wrong? Perhaps libertarian arguments are not compelling. (That is my own view.) Or perhaps parents and communities are raising their kids to be other than libertarians. A shelfload of books and articles by the likes of Hayek, Nozick, and Ayn Rand cannot counteract powerful socialization by millions of parents.

I mentioned an example in my last post, but let me spell it out a little more. In some metropolitan areas, there’s a stark contrast between neat, safe, prosperous private communities in which open displays of political opinion are banned, and poor, relatively high-crime urban neighborhoods in which you often see political signs and even some picketers and canvassers. There is also a contrast between fancy suburban malls—considered private property—in which canvassing and leafleting are banned, and decrepit urban streets in which you can see all kinds of political speech, including graffiti. If millions of kids grow up in communities that are wealthy but intolerant of public speech, they are likely to draw the conclusion that speech is detrimental to order and prosperity. As I wrote in my last post, this is political socialization for fascism.

Libertarians are loath to restrict private contracts, even those that voluntarily restrict speech. They have a point: we aren’t free if we cannot associate in intolerant communities. But if many people choose to ban freedom within their commonly-owned private property, then they are highly unlikely to raise libertarian kids. This is a big problem for libertarianism. Paper guarantees of freedom mean nothing if most people are against freedom.

The great libertarian economist Frank Knight wrote in 1939:

The individual cannot be the datum for the purposes of social policy, because he is largely formed by the social process, and the nature of the individual must be affected by social action. Consequently, social policy must be judged by the kind of individuals that are produced by or under it, and not merely by the type of relations which subsist among individuals taken as they stand.

Moral: if you want libertarian policies, you need "social processes" that make people libertarians, and those policies may not arise as a result of free choices by individuals "taken as they stand." What's more, free parents make choices that overwhelmingly shape their children, which means that there can be tradeoffs between parental liberty and the liberty of the next generation. As Knight wrote, "liberalism is more 'familism' than literal individualism." But if families don't produce children who strongly prize freedom, then liberalism and "familism" will work at cross purposes.

Posted by peterlevine at 11:51 AM | Comments (4) | TrackBack

June 4, 2004

condos, gated communities, and shadow governments

Montréal: I’m at a Liberty Fund conference on private neighborhood associations. The Liberty Fund is a basically libertarian foundation that organizes more than 100 small conferences a year. The participants are not all libertarians—or else I would not have been invited.

It turns out that some 50 million Americans now live in some kind of community governed by an association: a condominium, cooperative, or a planned community with a board. Often a developer subdivides some land or constructs an apartment building and sells the units with deeds that (a) impose numerous rules on the buyer; and (b) create a board or other body that can legislate further and enforce existing rules.

These are voluntary associations: you don’t have to buy a house or an apartment in any particular condo or planned community. At the same time, they act like governments, taxing, regulating and fining residents and enforcing their decisions in courts. Indeed, they are more powerful than conventional governments, which are restrained by the Constitution of the United States. Residential associations can, and actually have, banned the display of signs critical of themselves, banned the sales of certain newspapers, even banned the private possession of materials they deem pornographic. The rationale for these rules is to increase property values, although the rules may also have other purposes, benign or malevolent.

These quasi-governments raise questions of interest to libertarians and others. For example:

Posted by peterlevine at 12:05 AM | Comments (4) | TrackBack

June 3, 2004

a few good sites

I don't usually list links; that seems a poor substitute for actually writing something here. However, I'm on my way to Montreal later this morning, with little time for blogging. Therefore, let me recommend ...

Posted by peterlevine at 7:30 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 2, 2004

memories of London in the seventies

I'm only 37. Almost half the population is older than me. Nevertheless, it's beginning to seem urgent to preserve certain generic memories before they slip away. For example, a hundred million or more Americans can remember as much of the 1970s as I can, but how many can remember being an American kid in London in that era? Sitting on stacks of old volumes in dusty antiquarian bookshops, reading Horatio Hornblower or Enid Blyton under the skeptical eye of the proprietor; wax paper sheets for toilet paper in the icy "gents" rooms--"Property of Her Majesty the Queen" printed on each sheet. On the streets: businessmen still in pinstripes and bowler hats, children in school uniforms, punks with spikes on their scalps, Indian refugees from Uganda, Saudis in white robes.

Standing when a master enters the classroom (a master with the right to cane us); calling other students by their last names. Warm orange "Squash" served to minors in small glasses in the back rooms of Edwardian pubs. Feeding coins into the electric space heater in the bathroom. Wallpaper with heavy raised patterns, deliberately painted white. German Jews from Hampstead and Chalk Farm fill the seats at chamber music concerts. No fast food--only "cafes" with eggs and sausage on the menu, and "Wimpy's" horrible English hamburger chain (the beef tastes cured), and Chinese takeouts that serve a fried egg on top of the rice; then a few Kentucky Fried Chicken outlets ("Do you 'ave them in America, too?"); and then a flood of McDonalds.

Strong accents mark the social classes, none of the more neutral "Thames Valley" dialect that now crosses class lines. Unreconstructed communists in the offices of public utilities frown on a Yankee bourgeois child. Older gents in cloth caps are amazingly proficient--professional, you might say--at boy's hobbies like stamp collecting, model trains, and wargaming with lead "figures." Parochial middle-class Englishness comes face-to-face with cosmopolitan outsiders in the great train stations, airports, and museums. Concorde roars overhead, petrol flows from the North Sea, James Bond is on the big screen: Britain is modern.

Obnoxious Americans upstairs in the double-decker busses. Nothing open on Sundays or evenings--which means waiting forlornly for the bus back to London after every business has closed and all one can see are TVs flickering through lace curtains. Perhaps Carter is on the tube, the US humiliated in Iran. The empty lots of London are bomb sites, cleared by the Germans in 1940. Reinforced concrete rises out of the rubble, surrounding old St. Paul's with brutalist office towers and apartments. Young "mums" with too many kids, chatting in the laundrette. Cadbury's chocolate bars in the Underground. Adventure playgrounds with murals painted by teenagers on the cement walls. Labour isn't working, Mrs. Thatcher, the Common Market, the National Front.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:05 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

June 1, 2004

map work

As regular readers know, my colleagues and I have been helping high school students to conduct fieldwork and make maps of their community. They are trying to understand how features of local geography may affect behaviors that, in turn, affect health. We and the students have collected mountains of data of various kinds: questionnaires, focus group notes, notes from "window tours" of the neighborhood, GIS data collected with Palm Pilots, ratings of local food sources, and more. Most of the data is incomplete and not yet suitable for drawing conclusions. Nevertheless, we need hypotheses so that we can narrow our focus.

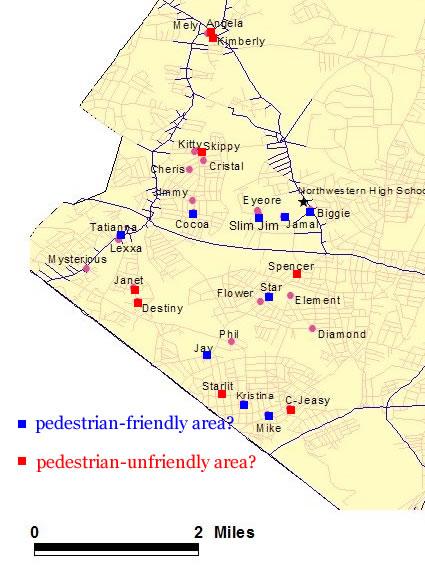

Here's a map, generated from the students' data, that suggests some ideas for our kids to pursue more rigorously. Each name is a pseudonym of a real student in our class.

The blue squares show students who appear to live in pedestrian-friendly areas. They say that they walk for exercise, they report that their neighbors walk a lot, and they say that it's safe to walk near their homes during the day.

The red squares mark students who answered "no" to at least two of the same questions, so they appear to live in pedestrian-unfriendly zones. The remaining dots mark students who gave mixed answers or no answers at all.

The cluster of red squares near the top of the map includes three young women of Caribbean ethnicity who live in single-family homes. Two of them say that it's safe to walk, but none say that they or their neighbors walk. (In general, females in our sample are less likely to report that their neighborhood is safe, but more likely to walk even if they feel unsafe.) The cluster of blue squares near Northwestern includes four African American young people, all apartment-dwellers, who walk and feel that walking is safe and common. There is a positive correlation between being African American and walking, in our small sample.

The real purpose of all this work is civic education--to teach students to understand and care about their communities, by engaging them in real research. This approach to education requires that we take their research questions very seriously ourselves. Although most of the information we have collected so far is simply confusing, I remain hopeful that we and our students can generate truly innovative findings about the effects of urban planning on health.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:27 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack