« December 2003 | Main | February 2004 »

January 30, 2004

the legality of invading Iraq

I am open to the possibility that the US invasion of Iraq will ultimately turn out to be a noble and successful battle against tyranny. Thus I am not eager to complain that the war was illegal. But the relevant documents suggest to me, unfortunately, that the US violated agreements to which we had subscribed. ...

The UN Charter is one of the few reasonably clear and binding elements of international law. Article 2 states: "All Members shall settle their international disputes by peaceful means in such a manner that international peace and security, and justice, are not endangered. All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations."

Thus invading another country is illegal. The Bush Administration claimed, however, that Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction (WMD's) in violation of specific UN resolutions and in ways that threatened our own national security. The US thus appointed itself as prosecutor, judge, and executioner in the case against Iraq. Unfortunately, the specific charges appear to have been false. It is no excuse to say that Saddam was guilty on other counts, such as tyranny against his own people. The rule of law demands that one is only punished if guilty as charged. Besides, the Bush Administration does not want to establish a precedent of overthrowing foreign governments for practicing tyranny, since that would commit us to action in 20-30 nations, several of them our allies.

The President and his defenders cite Saddam's failure to cooperate with UN inspections as grounds for war. (In effect, they explain the 2003 invasion as a resumption of the first Gulf War, justified because Saddam failed to comply with the terms of the original cease fire.) Now the relevant document becomes UN Resolution 1441, introduced by the US and allies in 2002, and approved by the Security Council.

I invite you to make your own judgment of this long resolution. To me, it seems a very thin thread on which to hang a war. At most, one could say that Iraq violated this passage and a few others: "false statements or omissions in the declarations submitted by Iraq pursuant to this resolution and failure by Iraq at any time to comply with, and cooperate fully in the implementation of, this resolution shall constitute a further material breach of Iraq’s obligations and will be reported to the Council for assessment in accordance with paragraphs 11 and 12 below."

Presumably, Iraq made false statements and refused to cooperate fully with inspectors. This was bad behavior, because it (a) disrespected the UN and international law and (b) suggested that Iraq actually possessed WMDs. Such bluffing undermines world peace. Note, however, that the resolution does not threaten war as a consequence of lying and stonewalling. It simply requires a report back to the Security Council.

I suspect that the President did not know he was speaking falsely when he claimed that Saddam had WMDs. Whether he and other top officials had deliberately distorted the intelligence is interesting, but not overly important. To me, the important point is that false statements justified a war. Two conclusions follow:

1. If the President leaves his own false statements on the public record and does not repudiate them, then they turn from errors into lies. One cannot state an extraordinarily consequential untruth and then leave it uncorrected. The President is not a liar, in my book--but he becomes one as soon as he fails to retract statements that he learns are untrue. If he is uncertain, then he is morally obliged to conduct a full and independent investigation that gets to the truth. Since David Kay's testimony, the clock is ticking; every day that the President fails to address the Kay's charges, his integrity looks worse.

2. The whole doctrine of preventive war is now in shambles, because its first application was the very thing that the UN Charter aims to prevent: an invasion without a legitimate casus belli. We named ourselves the world's police, but our case was false.

Posted by peterlevine at 01:24 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

January 29, 2004

cyberbalkanization

There's a lively discussion of "cyberbalkanization" on the Deliberative Democracy Consortium's blog. The discussion was prompted by a New York Times article last Sunday that claimed that people use the Internet to sort themselves into small, homogeneous groups and to filter out views that don't interest or please them. I've pasted my comment below, but I recommend the full discussion:

For my money, the best theoretical account of cyberbalkanization is still a 1996 paper by Marshall van Alstyne and Erik Brynjolfsson. They predict that the Internet will help people who are so inclined to increase the range and diversity of their information and contacts. They also predict that the Internet will allow people to "filter" out unwelcome ideas or contacts and to form narrow, exclusive groups. So the technology will not determine the outcome; people's motives will. And clearly, people have various motives. Some prefer diverse ideas and serendipitous encounters; others want to shun people who are different and simply confirm their own prejudices.

I am fairly pessimistic about the cyberbalkanization problem, not because of the technology, but because of cultural trends in the US. Niche marketing has become highly sophisticated and has divided us into small groups. There's more money to be made through niche programs than by creating diverse forums for discussion. Meanwhile, people have developed consumerist attitudes towards news, looking for "news products" that are tailored to their private needs. And broad-based organizations have mostly shrunk since the 1950s. In this context, the Internet looks like a means to more balkanization. In a different context, such as contemporary Saudi Arabia, it may have a much more positive impact.

Posted by peterlevine at 12:53 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

January 28, 2004

jury duty

I was in the pool for jury duty today, although I was not selected for a panel. (This happens like clockwork every two years.) I used to want to be selected, because I study deliberation, and a jury is the paradigm of a deliberative body. Now I quietly hope that my number won't come up; I feel I have too much to do at work--perhaps an indication that I'm putting too low a priority on civic duty. Anyway, they never seem to want me.

Waiting in the pool is, however, a nice chance to observe a random selection of my fellow Washingtonians. I have noticed, for example, that African Americans are much more likely than Whites to see someone else in the jury pool whom they already know. (The Black community is more stable, and residents are more likely to have gone to local schools.) Also, a striking percentage of jurors name someone in their family who serves in law enforcement. This is probably a DC phenomenon: we have numerous layers of police, prisons, and federal law-enforcement agencies here.

While in the courthouse, I helped my CIRCLE colleagues put out a press release on youth voting in New Hampshire. In Iowa, youth turnout quadrupled compared to 2004. In New Hampshire, it's hard to say what happened to turnout. There was no contested Republican primary, so New Hampshire Independents who might usually vote in the GOP primary voted in the Democratic contest. Voting by all age groups increased in the Democratic primary, but this seems meaningless. Furthermore, the under-30's did not increase their share of the vote, as they had in Iowa. I wonder whether youth turnout was lower in New Hampshire than in Iowa because some young Dean supporters became disillusioned during the last week. Dean came first among the under-30s in New Hampshire, but some of his young fans may have stayed home.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:00 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

January 27, 2004

online organizations

I've been asked to write an article on how young political activists use the Internet. After an introduction about the political potential of the "commons," I turn to various types of online youth activity. One short section concerns online political organizations. Comments would be welcome. I'm planning to say:

Political, ideological, and civic organizations have formed largely or entirely online, representing virtually all ideologies, identities, and agendas. Their organizational structures also vary greatly, but compared to offline groups, they are more likely to have anonymous or pseudonymous members. Anonymity has the advantage of allowing candor, which is especially beneficial for members of stigmatized groups (such as the only gay adolescent in a small community). It also allows people to experiment with novel identities. However, anonymity may have the disadvantage of making relationships relatively superficial and may permit behavior that is disruptive to the group itself. If members can adopt fictitious identities, then they can change their identities as soon as anyone threatens to expel or socially ostracize them.

Compared to offline groups, online ones tend to be easier to “exit” but harder to change by exercising “voice” (Hirschman), because there is no method of democratic decision-making that one can influence. Because exit is easy, groups tend not to discipline their own members by demanding contributions or particular forms of behavior in return for membership. Again compared to offline groups, online ones tend to be “thin” rather than “thick” (Bimber, p. 148). In a classic “thick” group, such as a family and ethnic group, members are committed to the survival and flourishing of the collectivity; but its purposes are changeable and subject to debate. In a “thin” group, members enter having some purpose, and view membership as instrumental to that goal. Although many online groups are “thin,” unstructured, and easy to exit, this is not true of massive, multiplayer games, whose participants invest considerable time in developing fictional characters. Often, they become highly committed to the flourishing of the game community as an end in itself.

However, most games are not political. Political or civic groups more typically allow members to visit a website, contribute money, and/or elect to receive email messages. A prominent example is MoveOn.org, a liberal organization in the United States that claims 2.3 million members as of January 2004. MoveOn was formed to oppose the impeachment of President Clinton, but now tackles issues that its members choose by voting. It has raised and spent millions of dollars to influence US policy. No information is available about the median age of MoveOn members or staff, but it has been described as an “an inter-generational grouping heavily peopled by young voters, something that most political constituencies lack” (Schechter, 2004).

Posted by peterlevine at 09:48 AM | Comments (1)

January 24, 2004

explaining politics to the very young

We've got kids (one 4 and one 14), and sometimes it's hard to explain the primary campaign to them. I've come up with the following key, which may come in handy for others who face the same predicament:

John Kerry = Pooh

Dick Gephardt = Rabbit

Al Sharpton = Gopher

Howard Dean = Tigger

Wesley Clark = Owl

John Edwards = Piglet

Joe Lieberman = Eeyore

Carol Mosely Braun = Kanga

Dennis Kucinich = Little Roo

George W. Bush = A Heffalump

Dick Cheney = A Woozle

Christopher Robin = The American People

Posted by peterlevine at 04:52 PM | Comments (3) | TrackBack

January 23, 2004

federal leverage over education

I attended a forum today on No Child Left Behind (NCLB), the major federal education law. The event took place in a U.S. House office building on Capitol Hill; it was organized by the American Youth Policy Forum.

I have long wondered how the federal government gains so much power simply by spending $30 billion/year on education from kindergarten through 12th grade. That's only 8 percent of education spending. NCLB is extremely unpopular in some areas, so I never understood why no local jurisdictions (or even states) have turned down the federal aid. Compliance is not mandatory; a state could pull out of the NCLB regime if it were willing to forego the money. From the complaints of many education leaders, it sounds as if the dollar costs imposed by NCLB are greater than the benefits. Today I learned that while federal monies cover 8 percent of the cost of k-12 education, they fund about half of state education agencies' costs. In other words, half of the salary positions in state departments of ed are directly dependent on federal funding. So these state agencies feel a need to comply with NCLB; and they have regulatory power over local jurisdictions. I don't know if this is true, but the source was knowledgeable, and it makes sense.

Posted by peterlevine at 03:56 PM | Comments (0)

January 22, 2004

Cole Campbell in Press Think

I'm with Cole Campbell at a Kettering Foundation event in Ohio. Cole is the former editor of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and a consistently interesting thinker about the media. It so happens that he is also the current "guest blogger" on PressThink. I strongly recommend his piece, which is about the way that the press has created the Democratic primary story line so far. Howard Dean is now the almost-dead-former-front-runner. His "goose is cooked," according to the latest punditry. But why was Dean the front-runner--indeed, the presumptive nominee--and why is he now on the ropes? All that voters have done is to participate in the overlooked Washington primary and the Iowa caucuses (where just 61,000 people participated). The rest of the epic of dramatic rises and collapses is all a media construction. Cole is able to call the press on this because they were wrong; Dean lost when they predicted that he would win. In the typical case, they are equally or more influential, but their predictions come true, so hardly anyone complains.

Cole adds that reporters refused to take any blame for their mistaken predictions, instead treating Dean as responsible for failing to live up to their expectations of him. Cole concludes:

Conventional wisdom was turned on its head tonight,' NBC's Tim Russert said during Monday night’s broadcast coverage of the Iowa caucus. Russert never owned up to who the keepers of conventional wisdom are-- he and his colleagues. The press tells itself that it is not implicated in the politics it molds and shapes. It presents itself as a campaign innocent. But everyone involved knows better.

It occurs to me that Dean's infamous scream during his "concession speech" gave the press some cover. They should have been saying: "We're sorry that we called the election wrong." Instead, they were able to say: "Dean's really a loser. Who knew?"

Posted by peterlevine at 12:34 PM | Comments (0)

January 21, 2004

Iowa thoughts

(Written in Oxford, OH): There is already too much post-Iowa punditry, but here are two points I would stress:

If we assume that there was some deliberation in Iowa (and not much peer-pressure), then we face a classic tradeoff. The Caucuses are especially valuable forms of democratic participation, but also especially difficult: lengthy, complicated, and "socially awkward." Thus they trade quantity of participation for quality. This is often a choice in the design of democratic institutions.

Posted by peterlevine at 09:11 PM | Comments (0)

January 20, 2004

young voters in Iowa

We're working on a press release to report that young people (ages 18-29) quadrupled their turnout in the Iowa Caucuses, compared to 2000. They voted at considerably higher rates than the 30-44 age group and represened almost as big a proportion of Caucus goers (17%) as of adult Iowa citizens (20%). If youth always participated at this rate, the 40 million Americans between the ages of 18 and 30 would be a major voting bloc.

There's another lesson for those of us who are interested in youth participation: young people may vote, but they aren't predictable. Slate quotes one Dean precinct captain who said, "I think if we could blame [Dean's loss] on anyone, blame it on the 18- to 25-year-olds, because they were nonexistent." Actually, they existed, and they turned out, but 35% of them went for Kerry and only 25% for Dean.

Posted by peterlevine at 03:38 PM | Comments (0)

January 19, 2004

What stories are worth reporting

Christopher Dickey, who covers Iraq for Newsweek, has decided against carrying a gun when he's in Baghdad. He doesn't think it would make him any safer. But he recognizes that reporters are in danger there; 19 have died so far. And he's increasingly unsure that it's worth risking journalists' lives to report the news from Iraq to an indifferent public. The TV networks have already cut their daily Iraq report to just over five minutes a day; and the public also seems to be losing interest. Dickey writes: "As my friend the newspaperman told me on a brief visit back to the States, 'You talk to people here about what's happening in Iraq and their eyes glaze over after two seconds. I mean, even members of your own family!'"

Dickey mentions deaths (of American military personnel and Iraqis) as topics that reporters do and should cover. But do we need such directly observed reports of violence in Iraq? Perhaps--failure to report casualties might give the impression that things were going better than they are, and it would prevent the public from mourning the dead. On the other hand, some might say that Americans are rightly somewhat inured to such stories. Perhaps we need a different kind of reporting: journalism that discusses deeper and more lasting issues.

I personally am not interested in detailed accounts of the latest car-bombings, but I do want to know how well Americans are doing at nation-buildng. If our soldiers and officers are doing a great job "on the ground," that is a story that should be celebrated as a model for civic work at home. If things are not going well, we should learn from their mistakes. Journalism about nation-building would be dangerous, and it might be overlooked by many Americans; but perhaps it would be more valuable than blow-by-blow descriptions of violence.

Posted by peterlevine at 10:40 AM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

January 16, 2004

the publicity game

We succeeded in getting some publicity for the survey that we released yesterday: articles in Reuters, Yahoo News, Washingtonpost.com, UPI, and USA Today, and an interview on CBS radio news. I was glad, because we wanted to publicize the survey so that people would be aware of it. Besides, we are held accountable for getting press coverage. That is why we spend significant amounts of money on a professional public relations firm.

I recently posted several critical comments about the pursuit of fame. I am well aware of the irony that days after I wrote those posts, I struggled to craft press releases that would maximize attention.

I'm not in imminent danger of actually becoming famous; but this behavior is just what troubles me. My colleagues and I sorted through miscellaneous data, looking for items that might interest particular kinds of reporters at this precise moment (i.e., days before the Iowa caucuses). Then we tried to write releases and other materials that would catch their attention. I believe that what we said was true, and that it is genuinely worthwhile to seek publicity. (Otherwise, what's the purpose of collecting information on a public issue?) Yet I see numerous snares and pitfalls.

First of all, the word "spin" applies, since we accentuated particular findings that we thought would capture attention. Second, it is not especially fair that we got media attention--however limited--for our survey, when thousands of academics labor in greater obscurity because they don't have p.r. budgets. In the intellectual marketplace, the best idea is supposed to win. In fact, the best funded idea has big advantages.

You may be reading this blog in small part because of the influence of money and its ability to attract attention. My website would score lower on Google search results if it weren't linked from my employers' elaborate and well-trafficked websites (see CIRCLE and the Maryland School of Public Affairs). These organizations, in turn, boost their profiles by spending money on p.r. We like to think of the "blogosphere" as a commons, as a free space in which one can acquire influence only by writing in ways that other bloggers find persuasive or inherently interesting. That is true to a degree. But my blog is surely not the only one that benefits from advantages stockpiled in the offline world.

Posted by peterlevine at 09:49 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

January 14, 2004

young people and Internet campaigns

We released a survey today that contains a lot of data about young people--their civic and political behavior and attitudes, and specifically their reaction to the ways political campaigns are using the Internet.Campaigns are effectively using the Internet to reach young people, and will

continue to do so

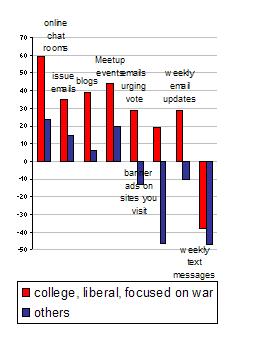

Despite a general lack of enthusiasm for many online campaign techniques, however, there are some pools of young voters who do like the new technologies. For example, those college students and college graduates who are liberal and concerned about the War in Iraq are overwhelmingly aware of blogs and favor their use in campaigns by 68%-32%. This group also likes “banner ads”and weekly email updates, which are unpopular among youth in general.

The graph shows the percentage who like each campaign technique, minus those who don't like it or call it a "turn-off." We distinguish liberal college students who are concerned about the war (red bars) from other youth (blue).

These findings put the Dean phenomenon in context. The demographic group that most likes his campaign themes is also most favorable toward electronic campaigning. It is not at all clear that blogs and Meetup events would work nearly as well for other candidates. Given that strong partisans and well-educated youth are most enthusiastic about the new technologies in politics, the Internet looks like a means to organize core voters, not a way to expand the franchise

Posted by peterlevine at 01:07 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

do business schools belong in universities?

I often ask myself this question as I arrive at work, since my office is in a building dominated by a business school. I'm all for programs that train effective business executives. But should these programs be subsidized by state universities and nonprofit institutions? Should they use academic norms such as tenure and peer-review? Why not just have for-profit training academies? There may be a great case for academic business schools, but I'm not sure.

For one thing, I'm not convinced that the debate in business schools is nearly broad or fundamental enough. In my university's Department of Government & Politics, faculty and students adopt and debate a wide variety of opinions. Some are anarchists or libertarians who are against both government and politics. Some want to see them radically changed. Others like and defend our current forms of politics and government. In contrast, business schools seem to treat businesses as self-evidently good. My own view is not hostile to business, but I do believe in robust debate in universities.

Perhaps it would be more fair to compare business schools to professional schools, which exist to train practitioners (not simply to promote debate). But even here, the comparison is not flattering to business schools. Quite a few law professors criticize the law wholesale, from various perspectives on the left and right. Even medical schools harbor radical critics of medicine, such as the libertarian Thomas Szasz. I do not see trenchant criticism of business coming out of business schools.

More important, business and medicine are professions that impose clearly defined public responsibilities on their members. Society subsidizes professional education, which is the only route to participation in certain fields. Because entrance to the "learned professions" is limited, those who graduate from professional schools can command high pay. But in return, we ask them to serve the public in specified ways. We impose no similar obligations on business people (with the exception of chartered public accountants). So do business schools belong in universities?

P.S., posted on Jan. 15: According to a story in the Chronicle of Higher Education, "Faculty members at leading business schools will join with the chief executive officers of some of the nation's top companies in a new ethics institute that will be housed at the University of Virginia's Darden Graduate School of Business Administration, officials announced on Wednesday." Sounds like a start ...

Posted by peterlevine at 12:24 PM | Comments (1)

January 13, 2004

surveys, websites, and other activities

Along with the Council for Excellence in Government, my organization, CIRCLE, will release a new poll of young Americans on Thursday. So I've spent a lot of my time helping to analyze the poll results and figure out a strategy for persuading the press to pay attention (even during the run-up to the Iowa Caucuses).

Meanwhile, I'm building a new website about--of all things--press coverage of the Iraq war. I'm responsible for a project to promote dialogue between political theorists and journalists. We decided to focus on a single issue: war coverage. Two graduate students did a lot of good research, but their time ran out before they could build a website to present their findings. So I'm building it, hoping that it will be the basis for some interesting online discussion.

I'm also trying to get a local project going. As I've mentioned before on this blog, we'll be working with high school students to build electronic maps of their community, highlighting those features of the local streets that affect people's decisions to exercise and to eat healthy food. We'll be working intensively this spring, with support from the National Geographic Foundation. So far, I've been doing preliminary tasks like getting permission to conduct research with minors. I'm also writing a couple of essays that are due within the month: one on our local oral history project, and one on youth online activism. Finally, I was recently elected chair of the steering committee of the group that's trying to implement the Civic Mission of Schools report. We'll go public with that effort when and if we receive funding. So far, we have worked hard on a couple of pending applications that would supply several million dollars if fully funded.

When I started blogging, I often used to describe my recent activities (as in today's post). I suppose I wanted an extra way to communicate with friends and family, and I hoped to present my work to a few strangers who might be interested in my activities. To an extent, I also wanted to document the life of an "engaged scholar." However, as the number of daily visitors rose considerably higher than I had expected, I began to view such personal updates as self-indulgent. Instead, I usually try to report or comment on public events and issues. This post is an exception, prompted by thinking about how my blog has evolved during its first year.

Posted by peterlevine at 05:05 PM | Comments (0)

January 12, 2004

happy birthday to this

This blog celebrated its first anniversary on Jan. 8, although I forgot to mark the day with an entry. (You can click here for the very first post.) Just a few days before I began to blog, I had moderated a conference panel on "communitarian approaches to cyberspace." Amitai Etzioni had selected the speakers, who included two of the most prominent--and best--bloggers in America: Eugene Volokh and Glenn Reynolds. I knew about blogs, but I didn't recognize these people. Before the panel, I had quickly looked them up on their respective universities' websites, saw nothing about their blogs, and therefore failed to mention what makes them both most famous. The panel discussion naturally focused on blogs and strengthened my feeling that I'd like to get into the game myself. Apparently, I wasn't the only one who reacted that way. The two other invited speakers were Jack Balkin and Amitai himself. Balkin started his fine blog on Jan. 10, 2003; Etizioni's equally good one was launched a few months later in '03.

(Incidentally, I don't see blogs as having very much to do with community in cyberspace. I deeply appreciate the frequent visitors to this site who leave posts or send me email, and I look frequently to see what they're up to online. In a couple of cases, they have volunteered invaluable assistance or advice. Nevertheless, I doubt that any of us would describe those occasional exchanges as a "community.")

Posted by peterlevine at 08:00 AM | Comments (4)

January 09, 2004

rural schools and civics

I met this morning with Rachel Tompkins, president of The Rural School and Community Trust. I was persuaded that civic education is exceptionally important in rural schools.

First of all, rural areas face serious economic and social problems because they are devalued--young people feel that they have to move to big cities to succeed. Developing a positive understanding of community (through research and activism) is part of civic education, and it could reduce the "brain drain." Second, many rural educators believe that rural schools are deprived of their fair share of state education funding. If we assume (for the sake of argument) that this is correct, then rural students can do themselves good and learn about civics by advocating for more funding. Third, it is a general truth that schools work best when they are supported by adult citizens who participate in a rich civic life, with lots of meetings, networks, and organizations. In rural areas, schools provide an essential mechanism for building such networks, and students can play important roles. Many of these factors also apply in urban schools, but we tend to forget about the rural sector. As Rachel points out in this interview, 14 percent of students live in areas with populations of 2,500 of smaller, and 98 percent of the nation's poorest counties are rural.

Posted by peterlevine at 01:01 PM | Comments (0)

January 08, 2004

taking responsibility

In yesterday's Washington Post, Barton Gellman shows pretty effectively that Iraq had no weapons of mass destruction after the early 1990s--but also that it was possible for American leaders to make an honest mistake about this. Saddam's history of using poison gas and his continued trickery made him look pretty guilty. I think, indeed, that he was deliberately bluffing.

So wouldn't it be refreshing and disarming (no pun intended) if the President said the following? "We have captured a wicked dictator who killed hundreds of thousands of his own people and waged war on his neighbors. We are now doing our level best to build a democratic state in the middle of an extremely important region. We told you that the reason for the war was fear of Saddam's weapons of mass destruction. Like President Clinton and many foreign leaders, we were genuinely convinced that Iraq had live chemical and biological weapons and an advanced nuclear program. We were wrong, and we take responsibility for our error. You may hold us accountable for this failure of analysis. But we made an understandable mistake which may lead to a tremendous amount of good."

George W. Bush is not the kind of guy who ever says things like this, and he would be a better leader if he did. However, it's also pretty obvious that the press, Democrats, and foreign leaders would jump all over him if he retracted his original reason for the war. We have a political culture that simply does not tolerate changes of mind, and that does not serve us well in times of deep uncertainty.

Posted by peterlevine at 03:21 PM | Comments (4) | TrackBack

January 07, 2004

quantitative and qualitative methods

I've recently seen two almost identical charts explaining the difference between qualitative and quantitative research. One was shown at a conference, the other presented in a graduate level methods textbook. I didn't save the charts, unfortunately, but this is how I recall them. (Similar charts can be found on the Web, e.g., here and or at the bottom of this page.)| quantitative | qualitative |

| detached | engaged |

| value-neutral | partial/committed |

| claims objectivity | admits subjectivity |

| seeks general findings | denies that general rules apply in cases |

| describes the mean | looks for exceptions, complications |

| pulls factors out of context | describes situations holistically |

| assumes certainty | presumes uncertainty |

| distinguishes causes from effects | does not presume to isolate causes |

I think this is a very misleading way to draw the distinction. Quantitative research means mathematical analysis; qualitative research means descriptions in words. The use of math requires quantification and a large enough sample to generate statistically meaningful results. The use of descriptive language requires enough detail about cases to generate insightful narratives or portraits. Both approaches are useful. Neither method implies positivism (a strict distinction between facts and values, or between facts and opinions), nor does either method imply skepticism or postmodernism. One can use quantitative methods--such as surveys and statistical analysis of the results--in a deeply engaged, critical, "political" way, without any illusions that one is objective. Or one can use qualitative methods--such as in-depth interviews--in a highly "positivistic" spirit (thinking that one has no values or biases and no axes to grind). Charts like the one above appeal to very general beliefs (or prejudices) about epistemology and drive us to favor either quantitative or qualitative methods. Instead, I think we should simply ask what can usefully be counted in particular cases, and what cannot.